The Star Trek Mirror Mirror beach towel ($20) features Juan Ortiz's retro-art celebrating one of the greatest classic Star Trek episodes, and the origin of the evil-twin/goatee trope.

Shared posts

Star Trek Mirror Mirror beach towel

omgitsbrilliant:livindavidaloki:redhjedi: The Hulk ain’t...

omgitsbrilliant:livindavidaloki:redhjedi:

The Hulk ain’t never lied.

I can’t even express how much respect I have for Mark Ruffalo. The dude’s on the US terrorism watchlist for fuck’s sake.

Omg, it’s true.

http://fuckyeahreactions.tumblr.com/post/93524596200

If You're Always Working, You're Never Working Well

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

The Best Marketing Strategy: A Sense of Humor

AD Round Up: Architecture of the Soviets

During the Soviet Union’s relatively brief and tumultuous history, the quest for national identity was one that consumed Russian culture. The decadence of Czarist society was shunned, and with it, the neoclassical architecture the Czars so loved. Communism brought with it an open frontier for artistic experimentation, particularly where public buildings were involved. It was on this frontier that Russian Constructivism was born, and some of Russia’s greatest buildings were built. This article on EnglishRussia.com compiles a list of some of the “best of the best” in Soviet architecture—and we liked it so much that we’ve compiled our own top ten list! See all of our favorite Soviet projects, after the break!

Amalir Sports and Concert Complex- Yerevan, Armenia

Railway Station- Dubulty, Latvia

Olympia Hotel- Tallinn, Estonia

Embassy of the USSR- Havana, Cuba

Tarelka Hotel- Dombai, Russia

Russian Academy of Sciences- Moscow, Russia

Regional Drama Centre- Grodno, Belarus

The House of the Soviets- Kaliningrad, Russia

The Palace of Ceremonial Rites- Tbilisi, Georgia

AD Round Up: Architecture of the Soviets originally appeared on ArchDaily, the most visited architecture website on 31 Jul 2014.

send to Twitter | Share on Facebook | What do you think about this?

Digital Artist Gets Super Creative with Self-Portrait Series, Shows You How It’s Done

![]()

Are you sick of the standard arm’s-length selfie? Or even the remote-triggered self-portrait? Well, photographer and talented Photoshop artist Martín De Pasquale was, so he turned his self-portraits up to eleven and created some reality-bending images that make that make those bathroom mirror selfies look even dumber.

The above video takes a BTS look at the process that goes into creating these compositions, and as straightforward as it looks at times throughout the demonstration, the amount of Photoshop skill De Pasquale has acquired over years of practice plays a major role in how effortless he makes this look.

Below is a collection of the Argentinian digital artist’s latest works. If you’d like to keep up with him and his conceptual endeavors, you can do so by heading over to his Behance profile:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(via Picture Correct)

Image credits: Photographs by Martín De Pasquale and used in accordance with Creative Commons license.

Photomicrographer Captures the Stunning, Jagged Landscapes Inside Gemstones

![]()

There is beauty in imperfection. In fact, imperfection might be considered the subject within a subject that photomicrographer Danny Sanchez tirelessly seeks out to create his stunning photography.

Sanchez’s main subjects are gemstones, but the colorful, alien ‘landscapes’ he captures are made up of imperfections called ‘inclusions’ that actually make a gem less valuable. You might say that one gem merchant’s trash is a gem photographer’s treasure.

Sanchez travels to gem shows and digs through bins worth of the precious stones to find the ones that, ironically, nobody actually wants. The ones that have “The stuff inside them.”

![]()

Once he’s found the perfect gem, he sets to work putting his eight years of experience to use setting up and capturing his shot… which is, it turns out, extremely challenging because he’s working with razor-thin depth of field.

When we caught up with Sanchez to ask him about the photographs, he was kind enough to outline how one of these pictures comes together:

In microscopy there is little to no depth of field. For photomicrography, this presents tremendous difficulty. Luckily, there are some very helpful mechanisms to help with this problem.

- Before anything else – lighting, lighting, lighting. Three continuous light sources, each with their own dual fiber optic light pipes, give me 6 finely focused, intensely bright “light guides”.

- A motorized stepping rig. Macro photographers are familiar with linear focusing rigs – this is just a vertical version that can hold a lot more weight. With this, I move 0.025mm at a time and take a photo until I’ve covered the depth I’m looking for. That can be up to 150 photos but usually it’s around 80. Those of you who like math, 80 photos at 0.025mm steps is 2mm depth of field.

- Stacking software. Specialized software that will take these 80+ images and render depth. I use Helicon Focus, but there are several fantastic options.

And that description leaves out the prepping of the gem before the shoot, and the Lightroom/Photoshop work after. Make no mistake, each of these gorgeous shots is a labor of love:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

To see more of Sanchez work, or if you’d like to see these shots in higher resolution — as you might imagine, the bigger you get the better with these photos… spectacular details just jump out at you — be sure to visit his website, where you can also buy prints.

Image credits: Photographs by Danny Sanchez and used with permission

Fun New Murals by ROA Utilize Tunisia’s Domed Architecture

Belgian street artist ROA (previously) is currently in Tunisia along with 150 other participating artists for Galerie Itinerrance’s Djerbahood open air museum project in Djerba, Tunisia. The artist cleverly took advantage of the many domed buildings in the city for several of his monochromatic spray paint murals that spread across multiple surfaces. You can see more recent pieces on the Djerbahood website. (via Savage Habit, Street Art News)

Bird: I eat things your size, but not like you. Cat: I eat things like you, but not your size.

How Karen Gillan embraced sci-fi stardom and baldness

Karen Gillan won legions of fans starring as Amy Pond, companion to Matt Smith's Tenth Doctor in Doctor Who. Since her run on the show ended, the Scottish actress has been making a name for herself on the movie circuit, headlining horror film Oculus and most recently appearing as the lethal hunter Nebula in Marvel's Guardians of the Galaxy.

Wired.co.uk sits down to chat with Gillan about the physicality of the role, the legacy ofWho, and the merits of baldness.

By: Matt Kamen,

Continue reading...The Imitation Game

The Imitation Game is a historical drama about Alan Turing, focusing on his efforts in breaking the Enigma code during WWII. Benedict Cumberbatch plays Alan Turing. Here's a trailer:

Tags: Alan Turing Benedict Cumberbatch Enigma movies The Imitation Game trailers video World War IIbutton, button

TadeuAlso inflation. Also "The Box".

this was an ’80s twilight zone episode based on a richard matheson short story

tune in tomorrow for more topical references

glitches in the matrix.

glitches in the matrix.

Neil deGrasse Tyson's Three Little Words to a Creationist Saying We Should Stop Searching for Extraterrestrial Life

thebagatellecardclub: izabeau: odendaikon: cover illust by...

cover illust by Naoki Urasawa

“THE BEATLES MATERIALS” vol.1 The Beatles

fuck, this is cool.

GLORIOUS

Overgrown, abandoned rollercoaster

From the Abandoned Geography Tumblr: an overgrown and abandoned rollercoaster in Hubei Province, China.

Abandoned roller coaster in Hubei Province, China ![]()

Communities Vs. Networks: To Which Do You Belong?

Tadeu“If you enter into too many of these bargains, you will split yourself into many specialized pieces, none of them completely human.” Because we divide ourselves between so many different networks, “no time is available to reintegrate” the different pieces of our personality.

In making his newest documentary, Korengal, author and filmmaker Sebastian Junger wanted to explore the answer to the question of why — despite its dangers and deprivations — men actually miss war when their tour of duty is over. A large part of the answer is the intense camaraderie created in combat — a brotherhood that they lack when they return home. In a recent interview, Junger posits that this absence of camaraderie is often at the root of why soldiers sometimes struggle so acutely to adjust to life after deployment. They come home, Junger says, and realize for the first time what an “alienated society” they truly live in. What they need, he argues, is a country that “operates in more of a community way.”

He then adds: “But frankly, that’s what we need.”

Unfortunately, true community in our modern world is hard to find for soldiers and civilians alike. Instead, we increasingly live out our lives as members of networks. This transition from community to network life is truly at the heart of the increasing feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and anomie that many people experience in the modern age. We’ve never been so “connected” — and yet so isolated at the same time.

While networks often borrow from the language of community, the two models of sociality are not the same. In an essay included in the book Dumbing Us Down, author John Gatto sharply elucidates the differences, and argues that if we truly want to experience “the Good Life” and develop fully as human beings, we need to spend more time in communities and less time in networks.

Today I will share some of Gatto’s key points, explore the way networks emptily ape communities, and touch on a few things we can all do to create a greater sense of community in our lives.

Networks vs. Communities

Networks Are Large and Anonymous; Communities Are Small and Intimate

With networks, the bigger they are the better. As Gatto notes, “’More’ may not be ‘better,’ but ‘more’ is always more profitable for the people who make a living out of networking.” Continually increasing in size may even be necessary for a network’s very survival. For example, as a platform like Facebook increases its number of employees, the cost of its servers, and its obligation to please shareholders, it has to keep on accumulating more and more users to stay afloat.

Because networks are so large, anonymity reigns. Members do not meet face-to-face, do not know if the people they interact with digitally are even who they say they are, and may have no idea who also belongs to the network. Because of the lack of physical intimacy, a culture of honor and shame cannot function, necessitating the erection of numerous rules and regulations to check and control members’ behavior.

In contrast, communities have inherent limits on size. Unlike networks, if communities don’t stop growing, they’ll die. According to Dunbar’s Number, most humans can’t maintain more than around 150 meaningful relationships. Anthropologists have found that hunter-gatherer societies hover around 150 members before they split. In Western military history, the size of a military company — the smallest autonomous and fully functioning unit — has been around 150 members.

If a community gets too big, people get overlooked. And because members no longer face the social scrutiny of their peers, they can opt out of contributing without shame or consequence. Once that disengagement happens, community life slowly begins to crumble.

Networks Are Artificial, Top-Down; Communities Are Organic, Bottom-Up

Networks are typically artificial; they rarely form organically. And they’re invariably created, and then governed, in a top-down fashion. Policies and regulations are decreed from on high with little or no input from the majority of the people who make up the network. Because those at the top are so removed physically and psychologically from those at the bottom, the solutions ultimately proffered are often out of touch and highly ineffective. Here’s a perfect example: The other day I was at a big-box retailer and mentioned to a cashier how warm it felt inside. She told me that the store’s thermostat was controlled from the corporate headquarters…in New Jersey. “They obviously don’t know how hot it gets here in Oklahoma,” she said with a sigh.

Even when the powers that be in a network ask for input from its lower-level members, the request for feedback is usually a token gesture lacking in any efficacy. For example, corporations sometimes survey their employees about their satisfaction with their job, but don’t make any changes after reviewing the results. Similarly, the White House has created the “We the People” petitioning system where, if 100,000 people sign a petition within 30 days, an official from the administration will offer a response; no action is taken beyond this token acknowledgement. When networks solicit feedback, the aim is to pacify members with the illusion, and only the illusion, of their having a voice and influence.

Communities, on the other hand, are organic and autonomous. They’re made up of a collection of real families that are bound together by geography and shared values. When facing a problem, individuals within a community band together to come up with a solution that will work for them. Because the people trying to address problems within the community — including its leaders — are familiar with the group’s unique needs, the solutions that are generated are typically more effective.

Networks Encourage Passivity and Consumption; Communities Require Action and Contribution

Because there are so many people in a network, members assume someone else will take care of problems that arise. But because that’s what everyone else is thinking, nothing gets done. People will step around someone in distress on the street in a big city, or pass the collection plate at a giant church, figuring other people will help. The anonymity of the crowd allows the passive bystander to escape shame.

Networks not only breed passivity, but encourage consumption. They’re all about what you can get, rather than what you must give. Oftentimes you can buy your way into networks, and because you’re paying for the service, you don’t feel obligated to offer any other form of contribution. The network doesn’t ask for anything either. It’s a business transaction. When you join a gym, for instance, once you pay your monthly dues your part of the deal is done — nothing else is expected of you. In a network, the members provide the money, and the network provides the experience. You are wholly consumer, rather than creator.

Even when contributions are mildly encouraged, because networks are large and anonymous, people can get away with taking from the pot but not adding to it. For example, you can join an online forum, and post some questions in order to pick the brains of other members. While it would be nice to offer advice in return, you’re certainly not obligated to do so. You can come in to a network, get what you need, and leave.

In contrast, in communities you get and you give; you can take from the collective pot, but you’re required to add to it too. There’s a sense of duty and obligation on this point. In a community, the group is small enough that people know who is and who isn’t being taken care of, and who is and who isn’t stepping in to help. If you don’t pull your weight and you’re perfectly capable of doing so, you face social repercussions.

Networks Can Be Location Independent; Communities Are Attached to a Place

With networks, you don’t actually have to be physically in the presence of the other members of the network to participate in the group. You can work from home for a corporation whose headquarters are halfway around the world or take part in online discussions about starting your own business while you’re vacationing in Thailand.

Communities, on the other hand, are attached to a physical place. They require you to be geographically close to your fellow community members. By necessitating physical presence, and face-to-face interactions, communities force individuals to be accountable to one another.

Networks Divide a Person Into Parts; Communities Nurture the Whole Person

Networks only ask for the part of a person that’s pertinent to that particular network’s limited and specialized aim. When we go to work, we don’t talk much about our politics or our religious beliefs (in fact, asking people about those things can get employers and co-workers in trouble with the law); when we attend PTA meetings, we don’t bring up our work; when we go to our CrossFit class, we talk burpees but not about burping babies. The offering of only one narrow slice of ourselves is especially pernicious on social networks like Facebook and Instagram, where we show others a glowing highlight reel of our lives, but hide the not-so-pretty behind-the-scenes parts.

By splitting the person up, the network promises efficiency. But according to Gatto, “this is, in fact, a devil’s bargain, since on the promise of some future gain one must surrender the wholeness of one’s present humanity. If you enter into too many of these bargains, you will split yourself into many specialized pieces, none of them completely human.” Because we divide ourselves between so many different networks, “no time is available to reintegrate” the different pieces of our personality. “This, ironically, is the destiny of many successful networkers and doubtless generates much business for divorce courts and therapists of a variety of persuasions.”

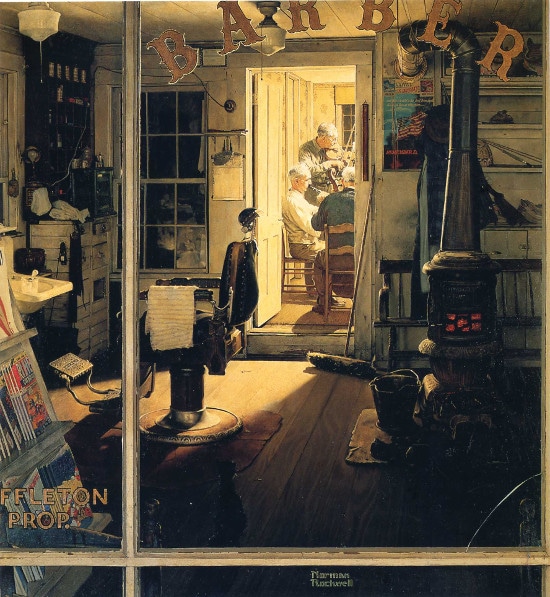

Communities, on the other hand, nurture the whole person. A community, as Gatto puts it, “is a place in which people face each other over time in all their human variety: good parts, bad parts, and all the rest.” There’s no identity splintering in a community. Yes, you may have the role of town barber, but people don’t treat you merely as a barber in one-off transactions. They treat you as Bill — husband to a wife with terminal cancer; father of three beautiful children; cantankerous man who’s capable of immense kindness; devout and dedicated deacon in his church who also happens to be a free-thinker. Oh, and you cut men’s hair for a living.

When a person suffers a crisis in a community (say for instance a debilitating accident), the community comes to help the whole person. Food is brought over; yard work is done; rooms are cleaned; hats are passed around; spiritual and emotional comfort is given. The same person steeped in network living would have to depend on paying strangers specialized in different areas to get the same sort of help: a cook, a house cleaner, a yard worker, and a therapist.

Is This Group I’m Part of a Network or a Community?

Ever since I learned about the network/community distinction, I’m continually analyzing whether the groups I belong to are one or the other.

In our modern age, intimate, face-to-face communities are hard to come by; while exceptions exist, networks have almost completely taken over how Americans socially organize themselves. So in evaluating the groups you belong to, it’s perhaps better to ask if they are more like a network, or more like a community. The following questions can help you think through where your group falls on the spectrum:

- Do the rules, regulations, and culture of my group come from top leaders that I have never met personally, or do they originate from the group itself?

- Do I know the names of every person in my group and interact with them face-to-face?

- Does my group have a physical meeting place?

- If I left the group, would anyone know I was gone? Would there be any repercussions for doing so?

- If I got sick, or needed a favor, how many members of my group could I count on for visits and assistance?

- Am I required to contribute to the communal pot, or can I utilize the benefits of the group without making any contributions beyond dues/fees/taxes?

Beware of Networks Wearing Community’s Clothing!

For most of human history we ran in small, intimate tribes. We’re social animals, and our brains are evolved for life in close groups. We crave the bonds and sense of belonging and stability that communities provide. In the modern age, these vital communities have disappeared, so we have turned to networks to fulfill our social needs.

But networks can never be a fully satisfying replacement for communities. They’re not designed for social intimacy and fulfillment — they’re designed for efficiency and growth.

And yet we continue to hold out hope that networks can perform a function for which they are fundamentally unsuited. And this hope is so tempting to buy into because many networks attempt to provide what Gatto calls “cartoon simulations of communities.” In other words, networks like to dress themselves up in the clothing of community.

For example, the idea of a “global community” has been much ballyhooed in our time (see The World Is Flat), but running it through the above requirements quickly reveals the idea to be an utter farce. If your only obligation to helping other members involves texting a $10 donation to aid tsunami victims every now and again, what you’re part of is a network, not a community.

Another perfect example of networks masquerading as communities is when giant corporations claim that they consider their employees and customers to be “family.” Except in the corporate version of “family,” members are charged for basic services and can be fired if another “brother” or “sister” will work more cheaply from India.

Marketers perpetrate what is perhaps the most insidious form of networks pretending to be communities. Taking a cue from religion — a strong source of community identity for tens of thousands of years — marketers have turned commercial brands into counterfeit communities. In his book Primalbranding, marketing expert Patrick Hanlon shows how businesses can turn their customers into cultish zealots by taking advantage of humanity’s innate desire to believe in something higher than themselves and to belong to a group. According to Hanlon, successful brands should mimic religious faiths by having a creation story, creeds, icons (logos), rituals, a charismatic leader, sacred words, and non-believers who the believers can use as a foil to buttress their identity.

Apple is perhaps the most successful of these pseudo-religious brands. We all know Apple’s creation story, we know their creed (Think Different), their ubiquitous half-eaten apple icon, their charismatic leader (Steve Jobs), and who the non-believers are (those philistine PC users). Apple even has their holy sanctuaries (the Apple Store). People who use Macs feel a connection to one another. Like they’re part of a community. Except they’re not.

The growing fitness industry is another example of the way in which businesses have done an excellent job of gilding what are really networks with the polish of community life. Enterprises like Crossfit and Tough Mudder have managed to make lots of money, while elevating their businesses into “movements” of loyal, zealous followers.

Online entrepreneurs have become especially adept at creating networks that have the veneer of community. Thanks to Seth Godin, many websites and blogs will have a big square in their sidebar saying something like “Join My Tribe! Sign up for my email newsletter!” But the idea of an online tribe completely contradicts what an actual tribe is. Members of true tribes live and work together on a daily basis, see each other face-to-face, are expected to contribute to the well-being of the tribe, and are rooted to a physical place. In online “tribes,” however, you’ll likely never see your fellow “tribesmen” in the flesh, you can drop out anytime, and your only interaction with other members will be about the specific topic that that particular online community is dedicated to, be it fitness or entrepreneurship.

(I should note that the forum section on The Art of Manliness was originally called the “Community.” I gave it that name back in 2009 when I didn’t know better. I naively hoped it could be a place where genuine community was fostered, but like all online forums, it’s definitely just a network. While the URL is still community.artofmanliness.com, instead of calling it the “Community,” I’m just going to start referring to it as the “Forum” because that’s what it is. You live and you learn.)

The façade of community quickly disappears when emergency strikes in your life and you really need somebody. Is the Apple community going to rally behind you and help you out? Of course not. Your fellow online “tribe” members might raise some money for you if they even know about your problem, but they won’t come visit you or provide actual human-to-human services. The fact that the only thing online communities can really do for their members is raise money is a telltale sign that they’re actually just networks and not communities. Community contributions should “pinch” — they should feel like a sacrifice. Lots of people are willing to click on a link to Paypal, but how many will come over to clean out your bedpan? As Gatto puts it, “when people in networks suffer, they suffer alone.”

The lack of genuine care from people in network life isn’t malicious. They are more than likely very caring people. The problem is they’re part of the network, and networks artificially divide us from each other. “I really would like to visit Jim, but you know, we’ve never hung out outside work, so it might be weird if I came by.” The unfortunate result of networked life is that it makes us feel lonely even when we’re surrounded by masses of people. Gatto describes the sad, shallow nature of networked life:

“With a network, what you get at the beginning is all you ever get. Networks don’t get better or worse; their limited purpose keeps them pretty much the same all the time, as there just isn’t much development possible. The pathological state which eventually develops out of these constant repetitions of thin human contact is a feeling that your “friends” and “colleagues” don’t really care about you beyond what you can do for them, that they have no curiosity about the way you manage your life, no curiosity about your hopes, fears, victories, defeats. The real truth is that the “friends” falsely mourned for their indifference were never friends, just fellow networkers from whom in fairness little should be expected beyond attention to the common interest.”

So beware of false tribes, which come to you in community’s clothing, but inwardly are ravening networks.

Learning How to Live in a Community Again

While I’ve certainly put the idea of networks through the ringer in this post, I don’t want folks to get the idea that they’re evil. They can serve a good purpose. They’re good for moving ahead in business, sharing information, raising money, and even meeting acquaintances that later turn into deeper relationships. They’re just not a replacement for true communities. Unfortunately we treat them as such. The result is a world where it is as if people eat only junk food, and don’t understand why their bodies are wasting away. Communities provide us with vital physical “nutrients” that we all need to thrive and be happy.

While it’s difficult to find “pure” tribe-like communities in our modern age, it is definitely possible to cultivate a greater community ethos in the groups you already participate in. As mentioned above, it’s better to not think of communities vs. networks as an either/or proposition, but rather as a spectrum. Churches, neighborhoods, schools, gyms, clubs, and so on can be more like networks or more like communities. Here are a few suggestions to move the ticker towards the latter:

Shoot for small. We’re made to run in tribes of around 150 people. When looking to join a church, deciding what school to send your kids to, or even joining a gym, keep that number in mind. Join groups where you’re able to know every other member by name.

Break larger groups into smaller ones. Belonging to a larger network isn’t a bad thing, if you can find a way to create smaller, more intimate groups within it. Megachurches, for example, often encourage members to join one of their many small groups in order to establish more close-knit bonds than are possible during their huge Sunday worship services.

Create you own tribes. Don’t just be a joiner. The best way to find a community is to start your own tribe. And when you do, don’t take the easy way out of borrowing a preformed, predefined structure; create your group’s culture from the ground up. People often ask me to start an official Art of Manliness men’s group. I have no plans to, because the result would be a top-down network, not a true community. It’s the latter that men need. You don’t need me to show you how to make your own fraternity of men — figure it out together with your brothers.

Get involved. The more passive people are, the more a potential community devolves into a network. For example, many people today treat public schools as a consumer transaction; I’ve paid my taxes, and once I drop my kid off at the curb, my part of the deal is done. Instead, you could volunteer and get involved with the school, get to know the teachers and the other families, and boost the school’s feeling of community. Same thing with your neighborhood — start actively finding ways to get to know the people on your block.

Meet physically. There are churches out there that offer online “services” where you watch the sermon online, give money online, and even pray and chat with other members online. The intention is good — bringing the bread of life to those who otherwise might not get it at all. But such a set-up only feeds one part of the soul; their need for community will remain famished. Online interactions can be fun and convenient — a supplement to our lives — but they can’t substitute for in-person meetings.

Share your whole self. The more your group encourages people to bring their whole self, rather than just a slice of it, the more the group feels like a community. For example, many corporate globo-gyms are soulless networks, but small powerlifting gyms often feel like communities, as the members not only know each other’s workout habits, but about their families and jobs, too.

Be prepared to sacrifice. Oftentimes people lament that they want to be part of communities, but what they really mean is that they want to enjoy the benefits of communities without having to deal with any of their responsibilities and hassles. They want to get, but not give. Being part of a community means not only taking from the pot, but putting into it; if you’re not willing to help out fellow members when they’re in need, and deal with the annoyances inherent to any close-knit group, you’ll never move beyond existing in a network.

Live by family. These final two suggestions will likely be controversial, but I would argue that they truly represent the best ways to be part of a community.

The heart of community is family; not just the nuclear family, but extended family. For centuries people lived near their parents and grandparents, along with their uncles, aunts, and cousins. They were your go-to, tight-knit support group. In our present age, one’s parents and siblings are strung out all across the country. You see them once a year at Christmas, and keep track of each other through your Facebook updates. Family has become just another network.

I have long struggled with the fact that while I’d like to live somewhere that allowed more opportunities for outdoor recreation, like Colorado or Vermont, both Kate and my parents and siblings are here in Oklahoma. I have long pondered which is better: living in a place you love, or living by family? While I still pine for the mountains, for now, family wins hands down. Our kids adore their grandparents (and vice versa!), and they’ll get to romp around with their cousins throughout their youth. They’ll get to feel like part of a familial community, rather than nodes in a disconnected network.

Some people relish being far from their families, because then they don’t have to participate in the inevitable hassle of familial drama. But that hassle is part and parcel of our humanity.

Don’t move very frequently. In order to form a community, you need to live and interact with the same people for a long time — to go through a myriad of ups and downs together. People will never know your whole self if you trade them in for new friends every two years. Community requires being rooted in a single place for an extended period of time.

The likelihood of 20-somethings moving to another state has fallen 40% since the 1980s. Various reasons for why young people are staying put have been floated: some posit that the trauma of the recession has made them risk-averse, that Facebook has made them less adventurous, or that they’re just plain unambitious. As such, my fellow Millennials have been derided as the “Go-Nowhere Generation.”

I’d venture to say there’s another reason for the trend that everyone else seems to have missed: my generation, having grown up socially famished in the vacuous network, now rightly craves the nourishment of true community.

A Flowchart

What toddler truisms are we missing?

Great Fortune

Although this is a comic about cookies ‘n cream ice cream, I stand by the fact that mint chip is by far the greatest ice cream flavor ever invented.

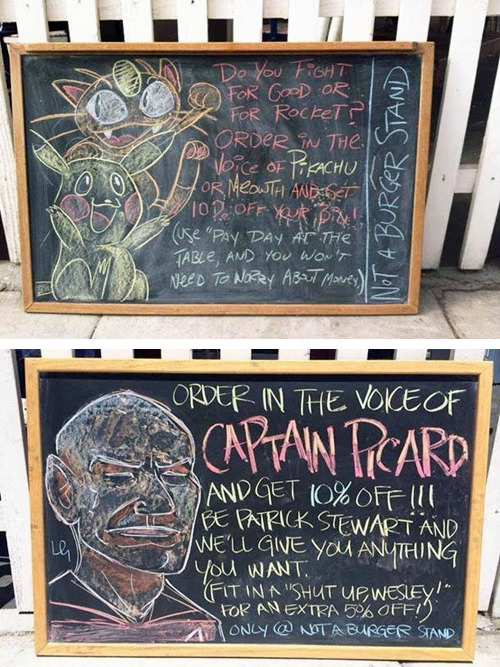

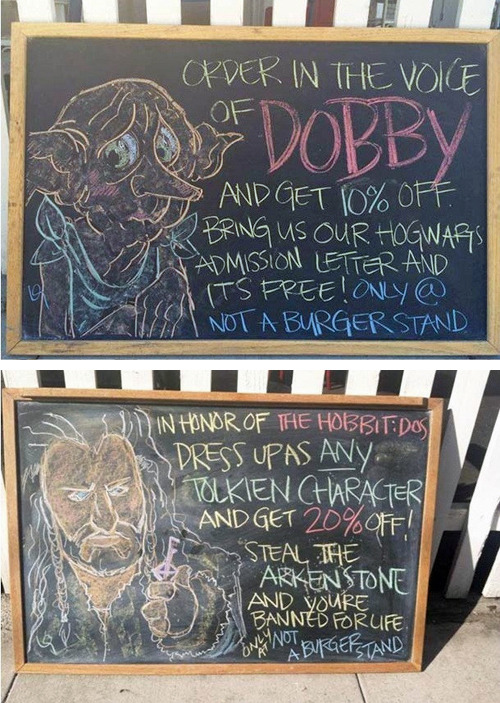

How to Get 10% Off Your Order at Not a Burger Stand in Burbank,...

How to Get 10% Off Your Order at Not a Burger Stand in Burbank, CA

Chalk art by Lila Roux

Previously: Funny and Creative Sandwich Board Signs