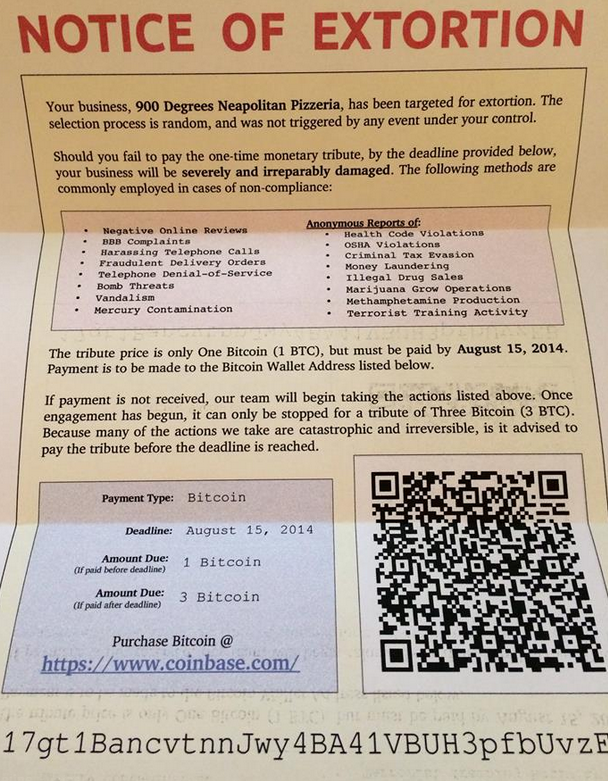

Security journalist Brian Krebs documents a string of escalating extortion crimes perpetrated with help from the net, and proposes that the growth of extortion as a tactic preferred over traditional identity theft and botnetting is driven by Bitcoin, which provides a safe way for crooks to get payouts from their victims.

Read the rest

Shared posts

Cyber-crooks turn to Bitcoin extortion

Great Job, Internet!: Welcome to the weird, blobby world of hand-painted foreign movie posters

The nations of Central and Eastern Europe have long been recognized in cinephile circles for their curious and idiosyncratic movie posters—ones far more daring and experimental than their cautious American counterparts, even when the films they’re ostensibly promoting are American in origin. A quick survey of Czech posters, Polish posters, and Hungarian posters reveals a whole world of startling, pseudo-psychedelic imagery designed not only to sell movie tickets but also to challenge viewers. There is even evidence to suggest that these works may have been subversive acts of political dissent during the era of communism.

Meanwhile, the bleakly-named blog Sad And Useless (which bills itself as “The Most Depressive Humor Site on the Internet”) has collected a few recent and semi-recent examples of what it is has inaccurately termed “Awkward Movie Posters from Russia.” The images, nearly all of which were taken from this LiveJournal account, are actually ...

Yahoo Resurrects ‘Community’ for a Sixth Season

#SixSeasonsandaMovie isn’t yet a dead idea. NBC canceled Dan Harmon‘s show Community earlier this year, but it seemed like there was still a chance that it would end up with a new home. Talks with Hulu didn’t go anywhere, but Yahoo wants a show — and now Yahoo has the sixth (and last?) season of Community. The deal was announced today just hours before the cast’s contract collectively expires. More details of the Community Yahoo deal are below.

Earlier, Dan Harmon tweeted something that was interpreted by some as a death for the show:

It's been so long since I've seen the young maiden. My love is stronger than my fear of death. #SixSeasonsAndAMovie

— Dan Harmon (@danharmon) June 30, 2014

But now we have this:

See you in the fall. #CommunityLivesOn pic.twitter.com/HSIzD0StT9

— Yahoo Screen (@YahooScreen) June 30, 2014

Yahoo has made a deal with producer Sony Pictures Television to stream a 13-episode sixth season of the show. Harmon will return as showrunner, and took a little swipe at NBC in his packaged statement about the Yahoo deal:

I am very pleased that Community will be returning for its predestined sixth season on Yahoo. I look forward to bringing our beloved NBC sitcom to a larger audience by moving it online. I vow to dominate our new competition. Rest easy, Big Bang Theory. Look out, Bang Bus!

Vulture suggests that the move to Yahoo won’t dramatically reduce the budget for this upcoming season. And Chris McKenna is in talks to return as exec producer.

And so the wild tale of Community continues — three solid seasons, followed by Harmon’s ouster, and the limp fourth season, then Harmon’s return for the fifth season. With this move, Community goes to a home with little experience running a show of this size, but which certainly has a long reach. Now we’ll see if any previously departed cast members return, and where talk of a movie goes.

Update: THR talked to Sony Pictures Television president of programming and production Zack Van Amburg, who said the entire cast is returning, and explained, “We try so hard and have a pretty decent record now of saving and/or rescuing some of our favorite shows, whether it’s Damages or Unforgettable.” He went on to say,

We had a series of conversations with NBC and finally Bob, as nicely as he could, said, “Stop f—ing calling me about Community!” [Laughs.] We pushed that one too much and we started to reach out to some of our other partners and networks. I saw it speculated in the press that there was decent interest from Hulu. That was true. We had a pretty advanced conversation. They have been an amazing partner; the show has done great things for them and their support has been beyond appreciated. It made sense that between Hulu and Comedy Central — who both currently carry the show — that maybe that was going to be our savior. We were in pretty advanced conversations with Hulu and we had made a half-dozen or so phone calls to other places. Then out of the blue — and this never happens — I got the best phone call in the world from Yahoo selling us on why Yahoo would be great destination [forCommunity]. To be honest, we were so far down the path with Hulu that, hopefully not arrogant but [we were], maybe a little bit dismissive of their overture, which made them that much more committed to explaining to us and to Joel McHale and Dan Harmon why this was going to be a cornerstone of the new Yahoo that they’re about to unveil to the world.

Finally, the exec joked “there’s no way we’re not making the movie now!” before going on to say,

I’d be lying if I told you that we have not had some very early and preliminary conversations that are very exciting about what a potential movie could be and who might direct it. It’s early but it’s completely in our thought process.

If the film happens, will it be a digital stream, or a theatrical release? That’s a question we can’t answer just yet.

- Hulu Exploring Ideas for a Sixth Season of ‘Community’

- Dan Harmon Discusses the Future of ‘Community’

- It’s the Darkest Timeline: ‘Community’ Canceled

- Dan Harmon Confirms ‘Community’ Return

- Marc Webb to Direct Showtime Musical Comedy ‘Crazy Ex-Girlfriend’

- Dan Harmon Will Not Be Showrunner For Fourth ‘Community’ Season, Responds to Sony/NBC

The post Yahoo Resurrects ‘Community’ for a Sixth Season appeared first on /Film.

someauthorgirl: xparrot: The interval between the start and...

The interval between the start and the end of “I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)” is 3 minutes and 30 seconds, and the International Space Station is moving is 7.66 km/s.

This means that if an astronaut on the ISS listens to “I’m Gonna Be”, in the time between the first beat of the song and the final lines …

… they will have traveled just about exactly 1,000 miles.

To be alive, now, in this age.

Why Are All the Cartoon Mothers Dead? - Sarah Boxer - The Atlantic

"The cartoonist Alison Bechdel once issued a challenge to the film industry with her now-famous test: show me a movie with at least two women in it who talk to each other about something besides a man. Here’s another challenge: show me an animated kids’ movie that has a named mother in it who lives until the credits roll. Guess what? Not many pass the test. And when I see a movie that does (Brave, Coraline, A Bug’s Life, Antz, The Incredibles, The Lion King, Fantastic Mr. Fox), I have to admit that I am shocked … and, well, just a tad wary."

Facebook's massive psychology experiment likely illegal

Researchers from Facebook, Cornell and UCSF published a paper describing a mass-scale experiment in which Facebook users' pages were manipulated to see if this could induce and spread certain emotional states.

Read the rest

Google Kills Orkut To Focus On YouTube, Blogger and Google+

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Meet Carla Shroder's New Favorite GUI-Textmode Hybrid Shell, Xiki

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

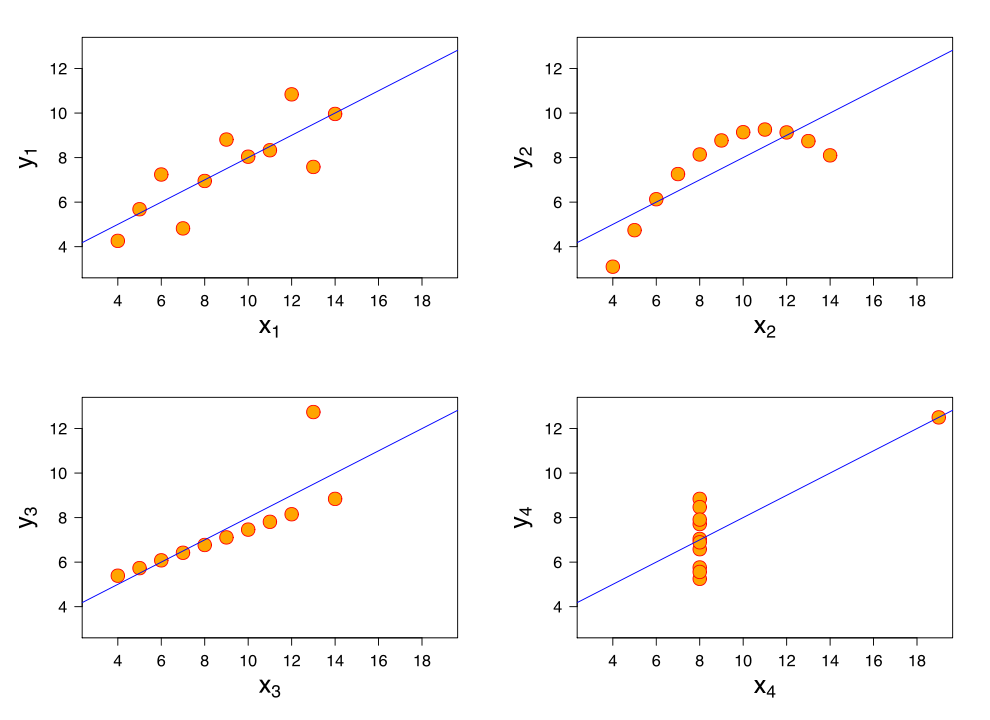

Stuff that every programmer should know: Data Visualization

Note: This post won't get you from zero to visualization expert, but hopefully it can pique your curiosity and will provide plenty of references for further study.

|

| Anscombe's quartet, from wikipedia. Data has the same statistics, but clearly different when visualized |

The second advantage, which is even more important, is that we can reason about the data much better in a visual form.

|

| This random number generator doesn't look good, but you won't tell from a table of its numbers... |

|

| Scatterplot, nifty to understand what dimensions are interesting in a many-dimensional dataset |

The other camp is about visualization of continuos data, often in the context of scientific visualization, where we are interested in representing our quantities without distortion, in a way that the are perceptually linear.

|

| CAVE, soon to be replaced by oculus rift |

But there are also times were we don't care about exact values but we seek for insight into processes of which we don't have exact mental models. This applies to all non-deterministic issues, networking, threading and so on, but also to many things that are deterministic in nature but have a complex behaviour, like memory hierarchy accesses and cache misses.

- Learn about perception caveats

Whatever your visualization is though, the first thing to be aware of is visual perception: not all visual cues are useful for quantitative analysis.

|

| Metacritic homepage has horrid bar graphs. As numbers are bright and below a variable-size image, games with longer images seem to have lower scores... |

Beware of color, one of the most abused, misunderstood tool for quantitative data. Color (hue) is extremely hard to get right, it's very subjective and it doesn't express well quantities nor relationships (what color is less than another), yet it's used everywhere.

|

| From complexdiagrams |

|

| A dependency matrix in NDepend |

Ideally though it would be lovely to be able to instrument compiled code, it's definitely possible but much more of an hassle without the support of a debugger. Another alternative that sometimes I adopt is to just have an external application peek at regular interval into my target's process memory.

It's simple enough but it captures data at a very low frequency so it's not always applicable, I use it most of the times not on programs running in realtime but as an live memory visualization while stepping through in a debugger.

Apple's recent Swift language seems a step into the right direction, and looks like it pulled some ideas from Bret Victor and Light Table.

Microsoft had a timid plugin for VisualStudio that did some very basic plotting that doesn't seem to be actively updated and another one for in-memory images, but what would be really needed is the ability to export data easily and in realtime as good visualizations are usually to be made ad-hoc for a specific problem.

|

| Cybertune/Tsunami |

It should perhaps not be surprising as reversers and hackers are very smart people, so it should be natural for them to use the best tools in their job.

And again visualization is a process of exploration, it can highlight some patterns and anomalies to then delve in further with more visualizations or by using other tools.

|

| Data entropy of an executable, graphed in hilbert order, shows signing keys locations. |

- Bonus links

Note that most of what you'll find on the topic nowadays is either infovis and data-driven journalism (explaining phenomenons via understandable, pretty graphics) or big-data analytics.

These are very interesting and I have included a few good examples below, but they are not usually what we seek, as domain experts we don't need to focus on aesthetics and communication, but on unbiased, clear quantitative data visualization. Be mindful of the difference.

- Some of my other posts

- Mathematica 101

- Peeking memory (this is great coupled with reflection or a language to define dependencies between data structures)

- Trace debugging from shaders

- Point clouds and processing

- Essential software

- Processing

- Python/IPython (anaconda), matplotlib (seaborn)

- Mathematica (mathics is interesting too)

- d3.js could be nifty too, especially if you already have a web frontend for your application as it's increasingly popular to do

- Don't use Excel, you'll waste time as it's very cumbersome to manipulate data there and its graphs are actually quite bad

- Books

- Tufte's works, starting with The Visual Display of Quantitative Information

- Now you see it and the other works of Stephen Few

- Information visualization, perception for design

- Software visualization

- The functional art

- Beautiful visualization

- Semiology of graphics

- Information visualization

- Data visualization principles and practice

- Talks

- Information visualization for scientific discovery

- Designing Data Visualizations

- BinVis hacking, Cantor Dust presentation

- Beauty of data visualization

- 10 Reasons why we visualize big data

- Memory hierarchy visualization

- Caltech symposium on datavis (introduction)

- One of many talks on the subject by Golan Levin (from the above mentioned symposium)

- Weather data art is quite amazing

- Other Articles and websites (be sure to check the links -inside- the post first)

- Brendan Gregg's work often use visualizations to investigate performance issues

- University of Maryland Visualization Course

- Coursera Data Science

- Visualizing algorithms

- Visual Complexity

- WTF Visualizations

- Visualizing

- Flowing Data

- Data visualization catalogue

- Harward data science

- Compressed sensing

- At one point you'll need dimensionality reduction:

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nonlinear_dimensionality_reduction

- http://jamesxli.blogspot.ca/2013/11/on-multidimensional-sorting.html

- http://homepage.tudelft.nl/19j49/t-SNE.html

- http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/82/05/37/PDF/distances.pdf

- http://fraka6.blogspot.ca/2013/11/visualizing-high-dimensional-data-pca.html

- http://research.ics.aalto.fi/mi/software/dredviz/

All made either in Mathematica or Processing and they are all interactive, realtime.

|

| Shader code performance metrics and deltas across versions |

|

| Debugging an offline backer (raytracer) by exporting float data and visualizing as point clouds |

|

| Approximation versus ground truth of BRDF normalization |

|

| Approximation versus ground truth of area lights |

|

| BRDF projection on planes (reasoning about environment lighting, card lighting) |

Netflix Could Be Classified As a 'Cybersecurity Threat' Under New CISPA Rules

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

"I’ve been a deep believer my whole life. 18 years as a...

"I’ve been a deep believer my whole life. 18 years as a Southern Baptist. More than 40 years as a mainline Protestant. I’m an ordained pastor. But it’s just stopped making sense to me. You see people doing terrible things in the name of religion, and you think: ‘Those people believe just as strongly as I do. They’re just as convinced as I am.’ And it just doesn’t make sense anymore. It doesn’t make sense to believe in a God that dabbles in people’s lives. If a plane crashes, and one person survives, everyone thanks God. They say: ‘God had a purpose for that person. God saved her for a reason!’ Do we not realize how cruel that is? Do we not realize how cruel it is to say that if God had a purpose for that person, he also had a purpose in killing everyone else on that plane? And a purpose in starving millions of children? A purpose in slavery and genocide? For every time you say that there’s a purpose behind one person’s success, you invalidate billions of people. You say there is a purpose to their suffering. And that’s just cruel."

The First World’s biggest addiction

My people have a ritual, and in fact I performed this ritual as I sat down to write what you’re reading.

It goes like this: I take a spoonful of special seeds and grind them down into a powder. I run hot water through the powder, and collect the dark liquid that seeps out. I take the cup of hot liquid and bring it to my desk because I believe drinking it will make for a better working experience.

Coming to the desk with this liquid is a tradition for millions of us because getting down to work first thing in the morning is traditionally a less-than-comfortable moment. We welcome anything that seems to make it more comfortable.

This liquid does that. As I drink it, I can feel it has immediate effects on my experience. I kind of feel like dancing, but instead of dancing, I type. I always look forward to the next time I have a chance to do it, sometimes even before I’m done. I don’t do it too often because I know that by the third time in a day, the ritual makes me tired and cranky.

I’ve made the ingestion of this substance an ordinary part of my day, and in fact I own specialized equipment for preparing it: one that grinds the beans into a powder for me, and another machine that makes the powder into the drinkable liquid. Mine is a fairly fancy one that makes a super-concentrated form of the liquid. If you don’t have one (or even if you do) there are also stores whose sole purpose is to have professionals make this liquid for you.

Interestingly, these seeds don’t grow within two thousand miles of me. But I have steady supply through a convoluted channel of farmers, marketers and middlemen. We call the seeds “beans” even though they are actually the pits of a tropical berry, which most of us have never seen.

The bean-liquid industry is worth 100 billion dollars worldwide, but there is another mind-altering liquid whose sales are expected to exceed 1 trillion dollars this year. It’s prepared differently, through fermenting plant materials. We have tried fermenting almost everything to make this stuff, and so there are all different types.

Its effects on your consciousness are a lot more dramatic. It gives you a certain confidence and sense of freedom. Its side-effects are quite reliably awful though. It makes you more careless and less intelligent. If you drink a lot of it (and it is common to drink this amount on purpose) it will make you nauseous, irresponsible and difficult to be around. Still, it is almost as popular as food.

The regular use of these liquids has become prominent in almost every society. Both made their way around the globe relatively quickly, and everywhere they went, they stayed.

The battle to be anywhere but here

The truth is we human beings are extremely interested in altering our state of consciousness. Even when we’re not using psychoactive substances to do it, we’re constantly trying to make our experience more bearable or more interesting by pulling out our phones, eating something, or flipping something on.

It is amazing what we will do to avoid letting a particular state of mind just be like it is without trying to change it. Why drink a liquid that costs a fortune and makes you fall down, unless you believe there is something seriously wrong with what you would otherwise feel like?

I think we underestimate how uncomfortable we are with most of our normal, unadulterated states. We try to have a lot more control over them than is really possible.

I just did it right now. A moment ago, I didn’t know what line to write next. I became uncomfortable for a moment, and almost got up to make coffee. Then I realized I had just finished a coffee, so instead I went to click on my Gmail, to see if I could find a hit of comfort there instead — even a small, temporary one that puts me right back into the same state a few moments later. It was such a minor discomfort that triggered this.

I have a whole arsenal of weapons I could have unleashed on my discomfort, which — if I hadn’t noticed what I was doing — could have led to an entire day of snacks, Netflix, apps and magazines. If I had gone down this road, I would have carried on until these activities became less comfortable than getting back to work, which does happen eventually, when that escapist glee runs out and turns into guilt.

Substances are especially popular weapons against boredom or discomfort, because they work a) immediately and b) reliably. They give us a kind of power we don’t normally have: direct control over a state of mind.

It’s natural for us to want to improve the quality of our state of mind. But we don’t need to. Most of us are so unaccustomed to voluntarily being with an unpleasant or uncertain state that we don’t even recognize those moments when we reach for the hammer-effect of substances or entertainment.

Even if we know some of these responses cost endless amounts of money, or reliably make us feel worse later, or do nothing but move a problem a few hours later into our lives, we still let the desire for an easier experience (right now) get the better of us. This need to attack all instances of discomfort with some kind of substance or technology becomes its own addiction.

What it costs us

The biggest downside to the state-avoidance habit isn’t that it costs us our money and our time. It’s that we are constantly forfeiting personal power. By reaching for the hammer (whether it’s a beer or a remote control) every time we’d like the moment to be a little easier or more interesting, we are training ourselves to be needy and dependent on circumstances.

By learning to allow different types of discomfort to simply stay in the room with you, without your scrambling for a button to push (real or metaphorical), you make discomfort matter less.

The pool of things you’re afraid of shrinks. It becomes a lot less important to control circumstances, because you know you can handle moments of uncertainty or awkwardness or disappointment without an escape plan.

On his blog, Jacob Lund Fisker often writes about the self-empowering habit of simply allowing discomfort to be a part of your experience sometimes. “Without discomfort, wants turn into needs and luxuries are treated as necessities.” He applied this principle methodically to all aspects of his life, and in five years it left him tough as nails and financially independent.

The more you dodge discomfort (or attack it with chemicals), the more you must dodge it, and the more it hurts when it finally corners you. And of course it will.

The key is noticing that moment in which you reach for the hammer — knowing when you’re trying to clobber your current experience into a more pleasant one. Knowing, and then refraining, is a powerful experience. Even if you do decide to take up arms against that moment, at least you are conscious of it.

No matter what you do, your life is going to be a largely uncontrolled parade of comfortable, uncomfortable and neutral developments. It can be quite a relief to let the comfortable and uncomfortable things arrive in their own time. Needs become simple preferences, and lose their power to strain the heart.

The bad parts become better because they don’t create desperation any more. The good parts become better too, because they’re not as hard fought and often arrive unexpected. And the in-between parts become at worst interesting, because they don’t have to be anything except what they already are.

***

Photo by Ben Cumming

***

The Fermi Paradox

Everyone feels something when they’re in a really good starry place on a really good starry night and they look up and see this:

Some people stick with the traditional, feeling struck by the epic beauty or blown away by the insane scale of the universe. Personally, I go for the old “existential meltdown followed by acting weird for the next half hour.” But everyone feels something.

Physicist Enrico Fermi felt something too—”Where is everybody?”

________________

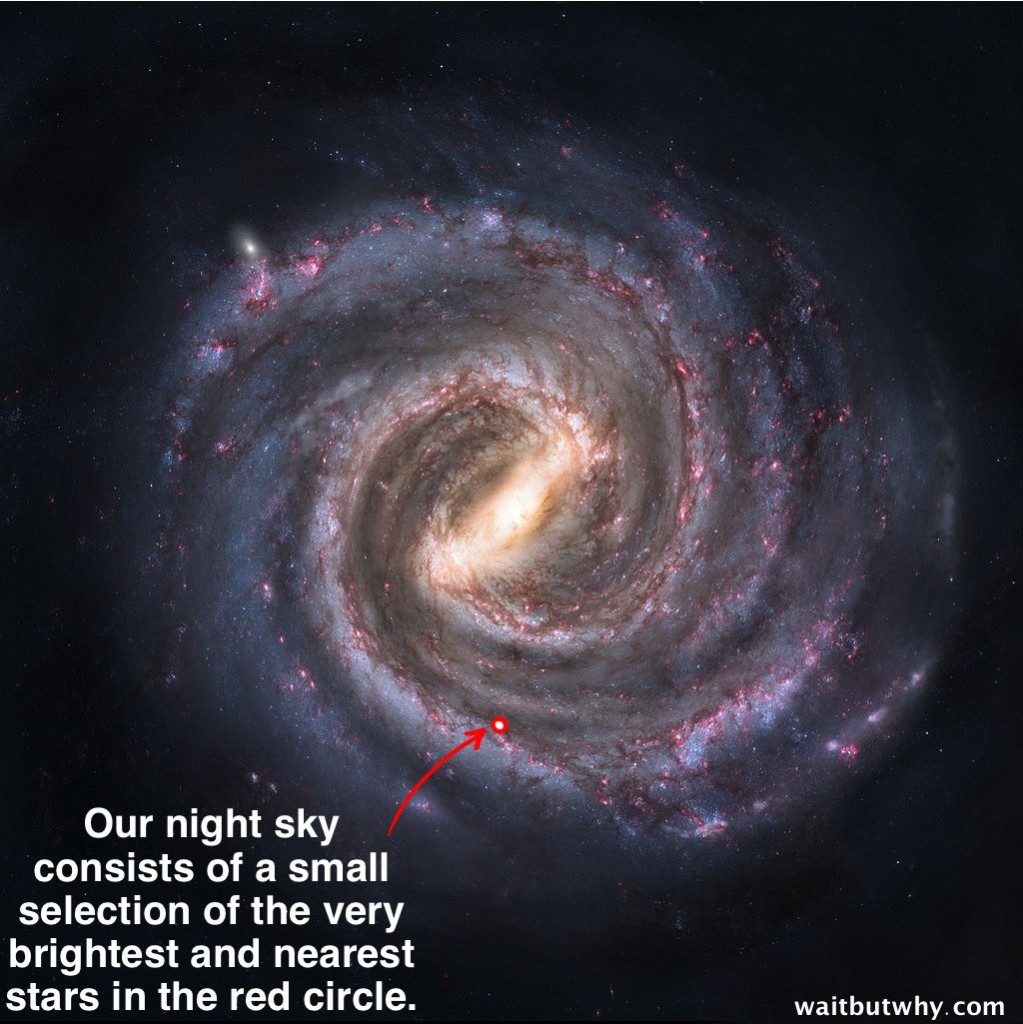

A really starry sky seems vast—but all we’re looking at is our very local neighborhood. On the very best nights, we can see up to about 2,500 stars (roughly one hundred-millionth of the stars in our galaxy), and almost all of them are less than 1,000 light years away from us (or 1% of the diameter of the Milky Way). So what we’re really looking at is this:

When confronted with the topic of stars and galaxies, a question that tantalizes most humans is, “Is there other intelligent life out there?” Let’s put some numbers to it (if you don’t like numbers, just read the bold)—

As many stars as there are in our galaxy (100 – 400 billion), there are roughly an equal number of galaxies in the observable universe—so for every star in the colossal Milky Way, there’s a whole galaxy out there. All together, that comes out to the typically quoted range of between 1022 and 1024 total stars, which means that for every grain of sand on Earth, there are 10,000 stars out there.

The science world isn’t in total agreement about what percentage of those stars are “sun-like” (similar in size, temperature, and luminosity)—opinions typically range from 5% to 20%. Going with the most conservative side of that (5%), and the lower end for the number of total stars (1022), gives us 500 quintillion, or 500 billion billion sun-like stars.

There’s also a debate over what percentage of those sun-like stars might be orbited by an Earth-like planet (one with similar temperature conditions that could have liquid water and potentially support life similar to that on Earth). Some say it’s as high as 50%, but let’s go with the more conservative 22% that came out of a recent PNAS study. That suggests that there’s a potentially-habitable Earth-like planet orbiting at least 1% of the total stars in the universe—a total of 100 billion billion Earth-like planets.

So there are 100 Earth-like planets for every grain of sand in the world. Think about that next time you’re on the beach.

Moving forward, we have no choice but to get completely speculative. Let’s imagine that after billions of years in existence, 1% of Earth-like planets develop life (if that’s true, every grain of sand would represent one planet with life on it). And imagine that on 1% of those planets, the life advances to an intelligent level like it did here on Earth. That would mean there were 10 quadrillion, or 10 million billion intelligent civilizations in the observable universe.

Moving back to just our galaxy, and doing the same math on the lowest estimate for stars in the Milky Way (100 billion), we’d estimate that there are 1 billion Earth-like planets and 100,000 intelligent civilizations in our galaxy.[1]The Drake Equation provides a formal method for this narrowing-down process we’re doing.

SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) is an organization dedicated to listening for signals from other intelligent life. If we’re right that there are 100,000 or more intelligent civilizations in our galaxy, and even a fraction of them are sending out radio waves or laser beams or other modes of attempting to contact others, shouldn’t SETI’s satellite array pick up all kinds of signals?

But it hasn’t. Not one. Ever.

Where is everybody?

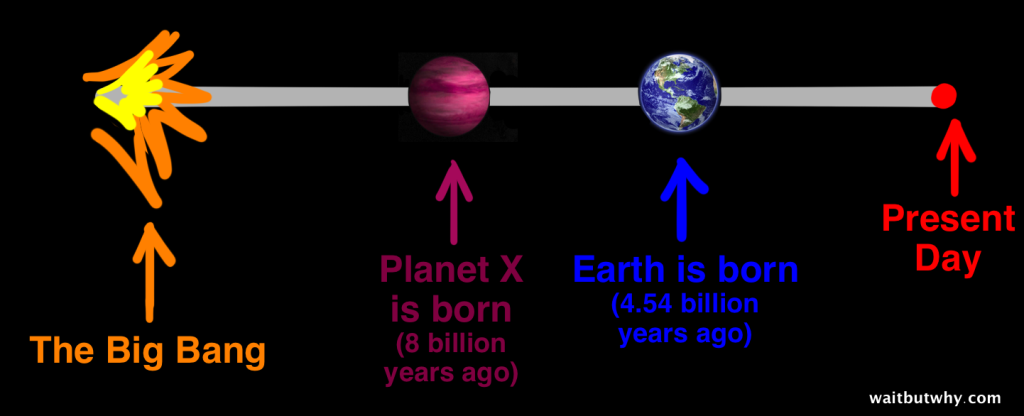

It gets stranger. Our sun is relatively young in the lifespan of the universe. There are far older stars with far older Earth-like planets, which should in theory mean civilizations far more advanced than our own. As an example, let’s compare our 4.54 billion-year-old Earth to a hypothetical 8 billion-year-old Planet X.

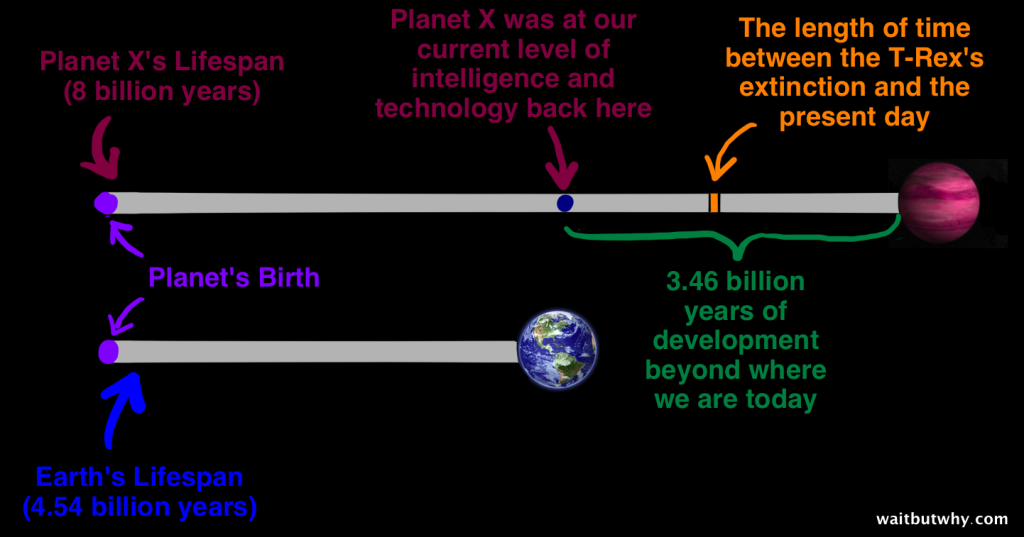

If Planet X has a similar story to Earth, let’s look at where their civilization would be today (using the orange timespan as a reference to show how huge the green timespan is):

The technology and knowledge of a civilization only 1,000 years ahead of us could be as shocking to us as our world would be to a medieval person. A civilization 1 million years ahead of us might be as incomprehensible to us as human culture is to chimpanzees. And Planet X is 3.4 billion years ahead of us…

There’s something called The Kardashev Scale, which helps us group intelligent civilizations into three broad categories by the amount of energy they use:

A Type I Civilization has the ability to use all of the energy on their planet. We’re not quite a Type I Civilization, but we’re close (Carl Sagan created a formula for this scale which puts us at a Type 0.7 Civilization).

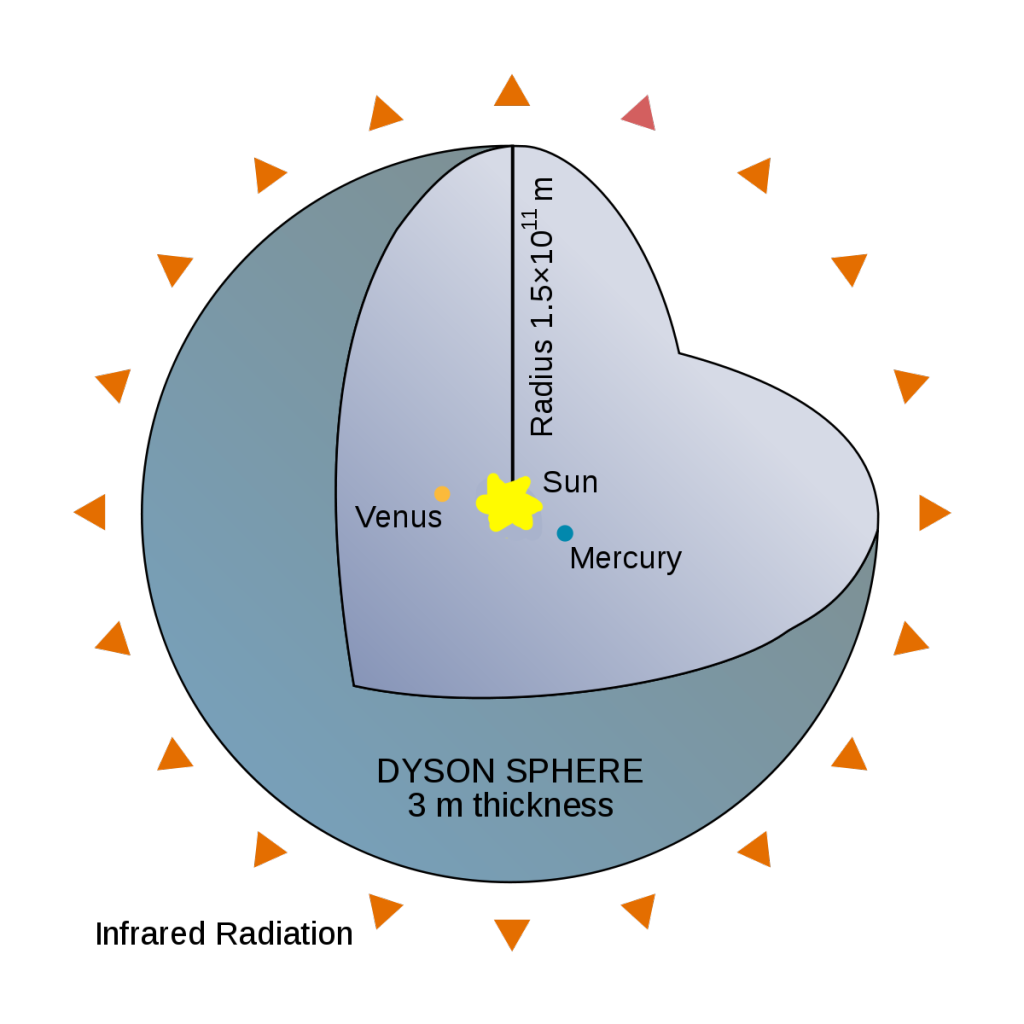

A Type II Civilization can harness all of the energy of their host star. Our feeble Type I brains can hardly imagine how someone would do this, but we’ve tried our best, imagining things like a Dyson Sphere.

A Type III Civilization blows the other two away, accessing power comparable to that of the entire Milky Way galaxy.

If this level of advancement sounds hard to believe, remember Planet X above and their 3.4 billion years of further development. If a civilization on Planet X were similar to ours and were able to survive all the way to Type III level, the natural thought is that they’d probably have mastered inter-stellar travel by now, possibly even colonizing the entire galaxy.

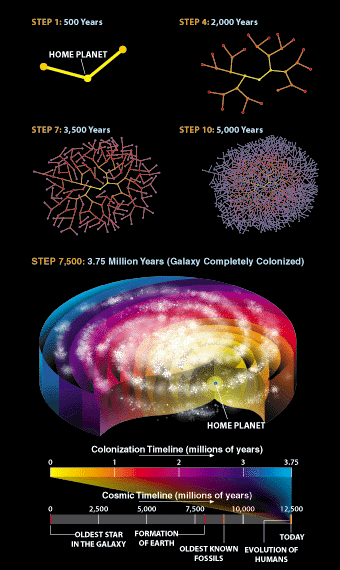

One hypothesis as to how galactic colonization could happen is by creating machinery that can travel to other planets, spend 500 years or so self-replicating using the raw materials on their new planet, and then send two replicas off to do the same thing. Even without traveling anywhere near the speed of light, this process would colonize the whole galaxy in 3.75 million years, a relative blink of an eye when talking in the scale of billions of years:

Source: Scientific American: “Where Are They”

Continuing to speculate, if 1% of intelligent life survives long enough to become a potentially galaxy-colonizing Type III Civilization, our calculations above suggest that there should be at least 1,000 Type III Civilizations in our galaxy alone—and given the power of such a civilization, their presence would likely be pretty noticeable. And yet, we see nothing, hear nothing, and we’re visited by no one.

So where is everybody?

_____________________

Welcome to the Fermi Paradox.

We have no answer to the Fermi Paradox—the best we can do is “possible explanations.” And if you ask ten different scientists what their hunch is about the correct one, you’ll get ten different answers. You know when you hear about humans of the past debating whether the Earth was round or if the sun revolved around the Earth or thinking that lightning happened because of Zeus, and they seem so primitive and in the dark? That’s about where we are with this topic.

In taking a look at some of the most-discussed possible explanations for the Fermi Paradox, let’s divide them into two broad categories—those explanations which assume that there’s no sign of Type II and Type III Civilizations because there are none of them out there, and those which assume they’re out there and we’re not seeing or hearing anything for other reasons:

Explanation Group 1: There are no signs of higher (Type II and III) civilizations because there are no higher civilizations in existence.

Those who subscribe to Group 1 explanations point to something called the non-exclusivity problem, which rebuffs any theory that says, “There are higher civilizations, but none of them have made any kind of contact with us because they all _____.” Group 1 people look at the math, which says there should be so many thousands (or millions) of higher civilizations, that at least one of them would be an exception to the rule. Even if a theory held for 99.99% of higher civilizations, the other .01% would behave differently and we’d become aware of their existence.

Therefore, say Group 1 explanations, it must be that there are no super-advanced civilizations. And since the math suggests that there are thousands of them just in our own galaxy, something else must be going on.

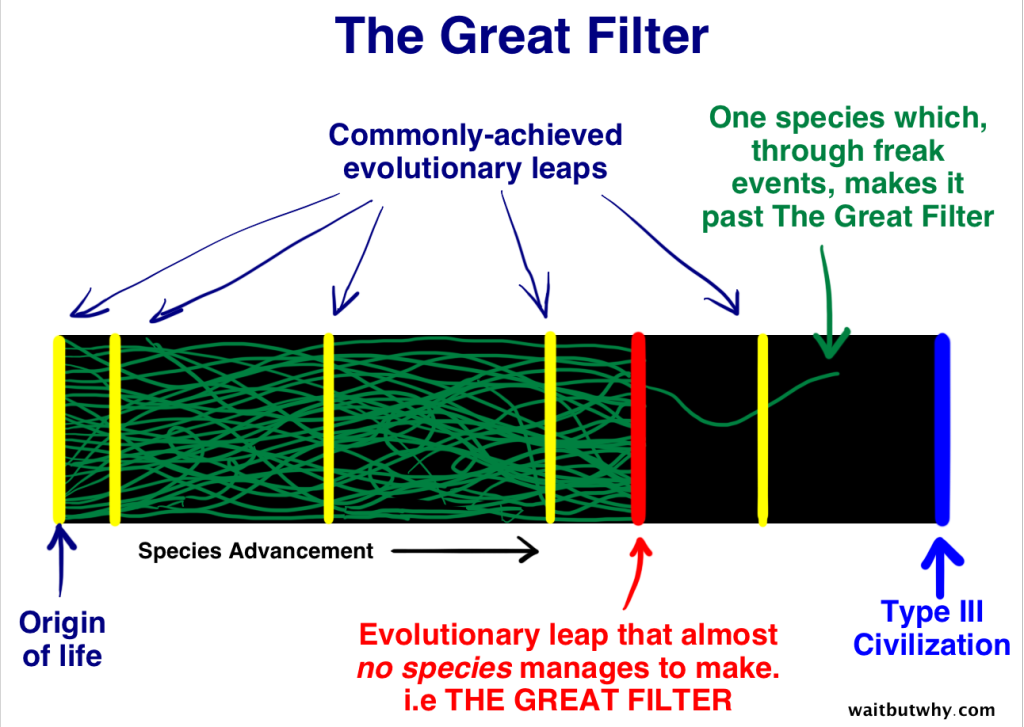

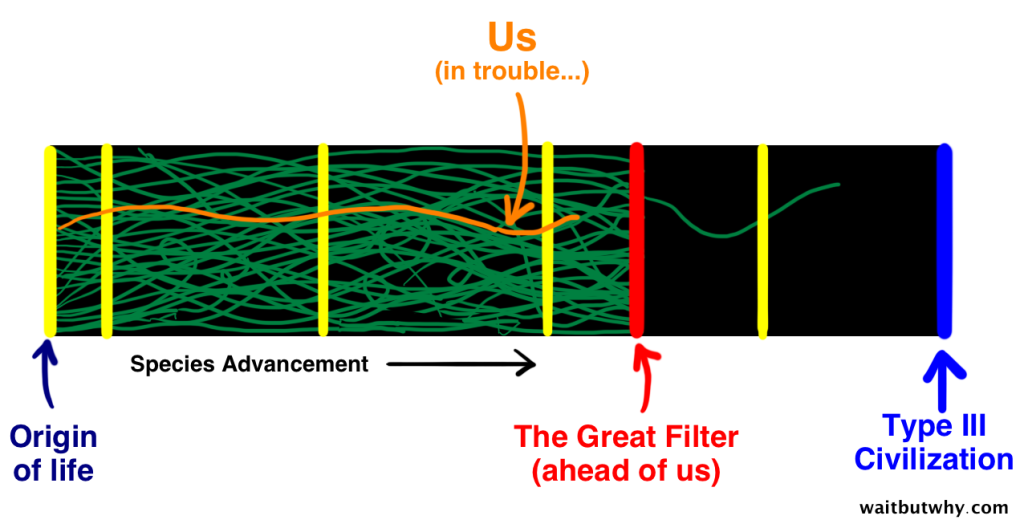

This something else is called The Great Filter.

The Great Filter theory says that at some point from pre-life to Type III intelligence, there’s a wall that all or nearly all attempts at life hit. There’s some stage in that long evolutionary process that is extremely unlikely or impossible for life to get beyond. That stage is The Great Filter.

If this theory is true, the big question is, Where in the timeline does the Great Filter occur?

It turns out that when it comes to the fate of humankind, this question is very important. Depending on where The Great Filter occurs, we’re left with three possible realities: We’re rare, we’re first, or we’re fucked.

1. We’re Rare (The Great Filter is Behind Us)

One hope we have is that The Great Filter is behind us—we managed to surpass it, which would mean it’s extremely rare for life to make it to our level of intelligence. The diagram below shows only two species making it past, and we’re one of them.

This scenario would explain why there are no Type III Civilizations…but it would also mean that we could be one of the few exceptions now that we’ve made it this far. It would mean we have hope. On the surface, this sounds a bit like people 500 years ago suggesting that the Earth is the center of the universe—it implies that we’re special. However, something scientists call “observation selection effect” suggests that anyone who is pondering their own rarity is inherently part of an intelligent life “success story”—and whether they’re actually rare or quite common, the thoughts they ponder and conclusions they draw will be identical. This forces us to admit that being special is at least a possibility.

And if we are special, when exactly did we become special—i.e. which step did we surpass that almost everyone else gets stuck on?

One possibility: The Great Filter could be at the very beginning—it might be incredibly unusual for life to begin at all. This is a candidate because it took about a billion years of Earth’s existence to finally happen, and because we have tried extensively to replicate that event in labs and have never been able to do it. If this is indeed The Great Filter, it would mean that not only is there no intelligent life out there, there may be no other life at all.

Another possibility: The Great Filter could be the jump from the simple prokaryote cell to the complex eukaryote cell. After prokaryotes came into being, they remained that way for almost two billion years before making the evolutionary jump to being complex and having a nucleus. If this is The Great Filter, it would mean the universe is teeming with simple prokaryote cells and almost nothing beyond that.

There are a number of other possibilities—some even think the most recent leap we’ve made to our current intelligence is a Great Filter candidate. While the leap from semi-intelligent life (chimps) to intelligent life (humans) doesn’t at first seem like a miraculous step, Steven Pinker rejects the idea of an inevitable “climb upward” of evolution: “Since evolution does not strive for a goal but just happens, it uses the adaptation most useful for a given ecological niche, and the fact that, on Earth, this led to technological intelligence only once so far may suggest that this outcome of natural selection is rare and hence by no means a certain development of the evolution of a tree of life.”

Most leaps do not qualify as Great Filter candidates. Any possible Great Filter must be one-in-a-billion type thing where one or more total freak occurrences need to happen to provide a crazy exception—for that reason, something like the jump from single-cell to multi-cellular life is ruled out, because it has occurred as many as 46 times, in isolated incidents, just on this planet alone. For the same reason, if we were to find a fossilized eukaryote cell on Mars, it would rule the above “simple-to-complex cell” leap out as a possible Great Filter (as well as anything before that point on the evolutionary chain)—because if it happened on both Earth and Mars, it’s almost definitely not a one-in-a-billion freak occurrence.

If we are indeed rare, it could be because of a fluky biological event, but it also could be attributed to what is called the Rare Earth Hypothesis, which suggests that though there may be many Earth-like planets, the particular conditions on Earth—whether related to the specifics of this solar system, its relationship with the moon (a moon that large is unusual for such a small planet and contributes to our particular weather and ocean conditions), or something about the planet itself—are exceptionally friendly to life.

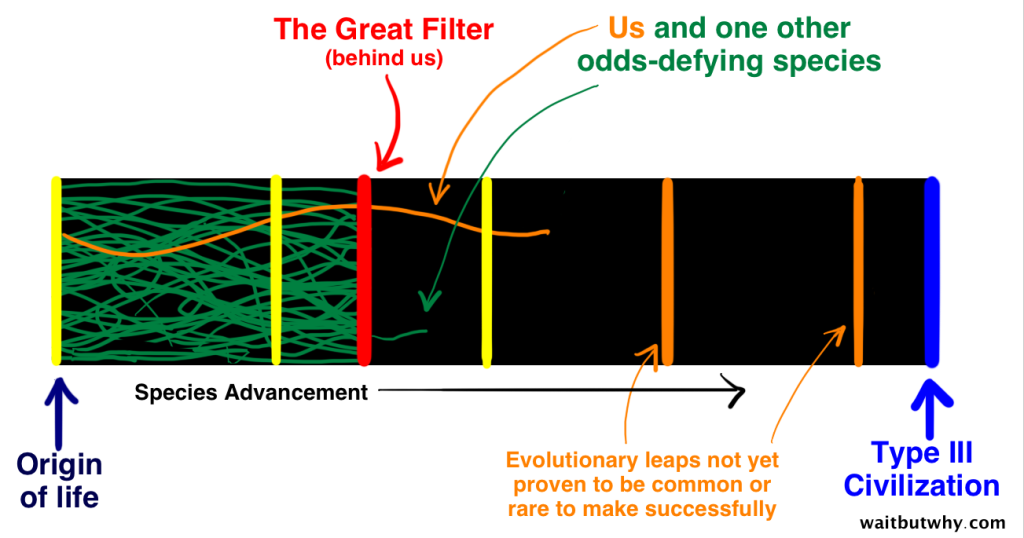

2. We’re the First

For Group 1 Thinkers, if the Great Filter is not behind us, the one hope we have is that conditions in the universe are just recently, for the first time since the Big Bang, reaching a place that would allow intelligent life to develop. In that case, we and many other species may be on our way to super-intelligence, and it simply hasn’t happened yet. We happen to be here at the right time to become one of the first super-intelligent civilizations.

One example of a phenomenon that could make this realistic is the prevalence of gamma-ray bursts, insanely huge explosions that we’ve observed in distant galaxies. In the same way that it took the early Earth a few hundred million years before the asteroids and volcanoes died down and life became possible, it could be that the first chunk of the universe’s existence was full of cataclysmic events like gamma-ray bursts that would incinerate everything nearby from time to time and prevent any life from developing past a certain stage. Now, perhaps, we’re in the midst of an astrobiological phase transition and this is the first time any life has been able to evolve for this long, uninterrupted.

3. We’re Fucked (The Great Filter is Ahead of Us)

If we’re neither rare nor early, Group 1 thinkers conclude that The Great Filter must be in our future. This would suggest that life regularly evolves to where we are, but that something prevents life from going much further and reaching high intelligence in almost all cases—and we’re unlikely to be an exception.

One possible future Great Filter is a regularly-occurring cataclysmic natural event, like the above-mentioned gamma-ray bursts, except they’re unfortunately not done yet and it’s just a matter of time before all life on Earth is suddenly wiped out by one. Another candidate is the possible inevitability that nearly all intelligent civilizations end up destroying themselves once a certain level of technology is reached.

This is why Oxford University philosopher Nick Bostrom says that “no news is good news.” The discovery of even simple life on Mars would be devastating, because it would cut out a number of potential Great Filters behind us. And if we were to find fossilized complex life on Mars, Bostrom says “it would be by far the worst news ever printed on a newspaper cover,” because it would mean The Great Filter is almost definitely ahead of us—ultimately dooming the species. Bostrom believes that when it comes to The Fermi Paradox, “the silence of the night sky is golden.”

Explanation Group 2: Type II and III intelligent civilizations are out there—and there are logical reasons why we might not have heard from them.

Group 2 explanations get rid of any notion that we’re rare or special or the first at anything—on the contrary, they believe in the Mediocrity Principle, whose starting point is that there is nothing unusual or rare about our galaxy, solar system, planet, or level of intelligence, until evidence proves otherwise. They’re also much less quick to assume that the lack of evidence of higher intelligence beings is evidence of their nonexistence—emphasizing the fact that our search for signals stretches only about 100 light years away from us (0.1% across the galaxy) and suggesting a number of possible explanations. Here are 10:

Possibility 1) Super-intelligent life could very well have already visited Earth, but before we were here. In the scheme of things, sentient humans have only been around for about 50,000 years, a little blip of time. If contact happened before then, it might have made some ducks flip out and run into the water and that’s it. Further, recorded history only goes back 5,500 years—a group of ancient hunter-gatherer tribes may have experienced some crazy alien shit, but they had no good way to tell anyone in the future about it.

Possibility 2) The galaxy has been colonized, but we just live in some desolate rural area of the galaxy. The Americas may have been colonized by Europeans long before anyone in a small Inuit tribe in far northern Canada realized it had happened. There could be an urbanization component to the interstellar dwellings of higher species, in which all the neighboring solar systems in a certain area are colonized and in communication, and it would be impractical and purposeless for anyone to deal with coming all the way out to the random part of the spiral where we live.

Possibility 3) The entire concept of physical colonization is a hilariously backward concept to a more advanced species. Remember the picture of the Type II Civilization above with the sphere around their star? With all that energy, they might have created a perfect environment for themselves that satisfies their every need. They might have crazy-advanced ways of reducing their need for resources and zero interest in leaving their happy utopia to explore the cold, empty, undeveloped universe.

An even more advanced civilization might view the entire physical world as a horribly primitive place, having long ago conquered their own biology and uploaded their brains to a virtual reality, eternal-life paradise. Living in the physical world of biology, mortality, wants, and needs might seem to them the way we view primitive ocean species living in the frigid, dark sea. FYI, thinking about another life form having bested mortality makes me incredibly jealous and upset.

Possibility 4) There are scary predator civilizations out there, and most intelligent life knows better than to broadcast any outgoing signals and advertise their location. This is an unpleasant concept and would help explain the lack of any signals being received by the SETI satellites. It also means that we might be the super naive newbies who are being unbelievably stupid and risky by ever broadcasting outward signals. There’s a debate going on currently about whether we should engage in METI (Messaging to Extraterrestrial Intelligence—the reverse of SETI) or not, and most people say we should not. Stephen Hawking warns, “If aliens visit us, the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn’t turn out well for the Native Americans.” Even Carl Sagan (a general believer that any civilization advanced enough for interstellar travel would be altruistic, not hostile) called the practice of METI “deeply unwise and immature,” and recommended that “the newest children in a strange and uncertain cosmos should listen quietly for a long time, patiently learning about the universe and comparing notes, before shouting into an unknown jungle that we do not understand.” Scary.[2]Thinking about this logically, I think we should disregard all the warnings get the outgoing signals rolling. If we catch the attention of super-advanced beings, yes, they might decide to wipe out our whole existence, but that’s not that different than our current fate (to each die within a century). And maybe, instead, they’d invite us to upload our brains into their eternal virtual utopia, which would solve the death problem and also probably allow me to achieve my childhood dream of bouncing around on the clouds. Sounds like a good gamble to me.

Possibility 5) There’s only one instance of higher-intelligent life—a “superpredator” civilization (like humans are here on Earth)—who is far more advanced than everyone else and keeps it that way by exterminating any intelligent civilization once they get past a certain level. This would suck. The way it might work is that it’s an inefficient use of resources to exterminate all emerging intelligences, maybe because most die out on their own. But past a certain point, the super beings make their move—because to them, an emerging intelligent species becomes like a virus as it starts to grow and spread. This theory suggests that whoever was the first in the galaxy to reach intelligence won, and now no one else has a chance. This would explain the lack of activity out there because it would keep the number of super-intelligent civilizations to just one.

Possibility 6) There’s plenty of activity and noise out there, but our technology is too primitive and we’re listening for the wrong things. Like walking into a modern-day office building, turning on a walkie-talkie, and when you hear no activity (which of course you wouldn’t hear because everyone’s texting, not using walkie-talkies), determining that the building must be empty. Or maybe, as Carl Sagan has pointed out, it could be that our minds work exponentially faster or slower than another form of intelligence out there—e.g. it takes them 12 years to say “Hello,” and when we hear that communication, it just sounds like white noise to us.

Possibility 7) We are receiving contact from other intelligent life, but the government is hiding it. This is an idiotic theory, but I had to mention it because it’s talked about so much.

Possibility 8) Higher civilizations are aware of us and observing us (AKA the “Zoo Hypothesis”). As far as we know, super-intelligent civilizations exist in a tightly-regulated galaxy, and our Earth is treated like part of a vast and protected national park, with a strict “Look but don’t touch” rule for planets like ours. We wouldn’t notice them, because if a far smarter species wanted to observe us, it would know how to easily do so without us realizing it. Maybe there’s a rule similar to the Star Trek’s “Prime Directive” which prohibits super-intelligent beings from making any open contact with lesser species like us or revealing themselves in any way, until the lesser species has reached a certain level of intelligence.

Possibility 9) Higher civilizations are here, all around us. But we’re too primitive to perceive them. Michio Kaku sums it up like this:

Lets say we have an ant hill in the middle of the forest. And right next to the ant hill, they’re building a ten-lane super-highway. And the question is “Would the ants be able to understand what a ten-lane super-highway is? Would the ants be able to understand the technology and the intentions of the beings building the highway next to them?

So it’s not that we can’t pick up the signals from Planet X using our technology, it’s that we can’t even comprehend what the beings from Planet X are or what they’re trying to do. It’s so beyond us that even if they really wanted to enlighten us, it would be like trying to teach ants about the internet.

Along those lines, this may also be an answer to “Well if there are so many fancy Type III Civilizations, why haven’t they contacted us yet?” To answer that, let’s ask ourselves—when Pizarro made his way into Peru, did he stop for a while at an anthill to try to communicate? Was he magnanimous, trying to help the ants in the anthill? Did he become hostile and slow his original mission down in order to smash the anthill apart? Or was the anthill of complete and utter and eternal irrelevance to Pizarro? That might be our situation here.

Possibility 10) We’re completely wrong about our reality. There are a lot of ways we could just be totally off with everything we think. The universe might appear one way and be something else entirely, like a hologram. Or maybe we’re the aliens and we were planted here as an experiment or as a form of fertilizer. There’s even a chance that we’re all part of a computer simulation by some researcher from another world, and other forms of life simply weren’t programmed into the simulation.

________________

As we continue along with our possibly-futile search for extraterrestrial intelligence, I’m not really sure what I’m rooting for. Frankly, learning either that we’re officially alone in the universe or that we’re officially joined by others would be creepy, which is a theme with all of the surreal storylines listed above—whatever the truth actually is, it’s mindblowing.

Beyond its shocking science fiction component, The Fermi Paradox also leaves me with a deep humbling. Not just the normal “Oh yeah, I’m microscopic and my existence lasts for three seconds” humbling that the universe always triggers. The Fermi Paradox brings out a sharper, more personal humbling, one that can only happen after spending hours of research hearing your species’ most renowned scientists present insane theories, change their minds again and again, and wildly contradict each other—reminding us that future generations will look at us the same way we see the ancient people who were sure that the stars were the underside of the dome of heaven, and they’ll think “Wow they really had no idea what was going on.”

Compounding all of this is the blow to our species’ self-esteem that comes with all of this talk about Type II and III Civilizations. Here on Earth, we’re the king of our little castle, proud ruler of the huge group of imbeciles who share the planet with us. And in this bubble with no competition and no one to judge us, it’s rare that we’re ever confronted with the concept of being a dramatically inferior species to anyone. But after spending a lot of time with Type II and III Civilizations over the past week, our power and pride are seeming a bit David Brent-esque.

That said, given that my normal outlook is that humanity is a lonely orphan on a tiny rock in the middle of a desolate universe, the humbling fact that we’re probably not as smart as we think we are, and the possibility that a lot of what we’re sure about might be wrong, sounds wonderful. It opens the door just a crack that maybe, just maybe, there might be more to the story than we realize.

To humble you further:

More from Wait But Why:

Why Generation Y Yuppies Are Unhappy

7 Ways to be Insufferable on Facebook

Why Procrastinators Procrastinate

How to Name a Baby

How to Pick Your Life Partner

Your Life in Weeks

10 Types of 30-Year-Old Single Guys

The Great Perils of Social Interaction

Sources:

PNAS: Prevalence of Earth-size planets orbiting Sun-like stars

SETI: The Drake Equation

NASA: Workshop Report on the Future of Intelligence In The Cosmos

Cornell University Library: The Fermi Paradox, Self-Replicating Probes, and the Interstellar Transportation Bandwidth

NCBI: Astrobiological phase transition: towards resolution of Fermi’s paradox

André Kukla: Extraterrestrials: A Philosophical Perspective

Nick Bostrom: Where Are They?

Science Direct: Galactic gradients, postbiological evolution and the apparent failure of SETI

Nature: Simulations back up theory that Universe is a hologram

Robin Hanson: The Great Filter – Are We Almost Past It?

John Dyson: Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation

Congo: A Group of Chimpanzees Seem to Have Mastered Fire

Ubundu| A group of bonobo apes living in the Salonga National Park, may have mastered the basic practice of creating and using fire. This particular group of almost three hundred specimens from this rare and extremely intelligent race of great apes, have been under close surveillance by a team of primatologist for the last three years, and seem to have recently developed a primitive fire building technique using rocks and twigs.

The bonobo, formerly called pygmy chimpanzees, is a omnivorous great ape found in a 500 000km2 area of the Congo Basin in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is mostly popularly known for its high levels of sexual behavior and its use of almost a dozen different primitive tools. Its level of intelligence is already considered to be almost unique amongst ape, being topped only by humans. Two bonobos at the Great Ape Trust in Iowa, Kanzi and Panbanisha, have been even taught how to communicate using a keyboard labeled with lexigrams (geometric symbols) and they can respond to spoken sentences. Kanzi’s vocabulary consists of more than 500 English words and he has comprehension of around 3,000 spoken English words.

It is however, the first time that a group of these primates develops some technical concepts as elaborate as these on their own. A few individual apes seem to have originally developed a rudimentary technique of rather poor efficiency, but the group gradually improved it through experimentation and observation over the last few months. They are now able to create and maintain a fire, which they have been using mostly to scare off predators and cook some of their food. Some individuals in particular among the group, seem to have rapidly grown a taste for cooked foodstuffs, especially flying squirrels. This also enabled the group to develop to a population which is much larger than has ever been encountered in the species, by bringing increased security and by diversifying food sources.

This absolutely astonishing evolution has gotten primatologists as well as many other scientists from around the world, really excited. This could be a unique occasion to study the evolution of a species during a crucial moment of its history, and could bring a lot of information concerning the early developments of humankind. The congolese rural population of the other hand have a very different perception of the situation, as “torch bearing apes” have been accused of setting fire to more than 1500km2 of forest since the beginning of the year, causing the death of three people.

6 vídeos de ilusão de ótica hipnotizantes

Aí vai uma lista hipnotizante com os 6 melhores vídeos de ilusão de ótica lançados em 2014 baseada na premiação “Best Illusion of the Year Contest”.

A premiação levando em conta a engenhosidade e a criatividade no desenvolvimento e criação no universo da ilusão visual no mundo. Veja só:

O The Dynamic Ebbinghau ficou em primeiro lugar. Consiste em um círculo central que é de um tamanho só mas parece mudar quando está rodeado por um conjunto de círculos.

Este pede pro espectador escolher uma das três estrada apontando a diferente. O resultado?

No “Pigeon-Neck Illusion” as listras dão a sensação de que os pombos estão mexendo as cabeças igual eles fazem de verdade.

Esse “Rotating McThatcher Illusion” é meio doidão.

“Infinite Maze” é um vídeo game em torno de uma ilusão de ótica inspirado no Pac-Man. Percebeu que o pac-man vai mudando os caminhos do labirinto?

Essas bolinhas parecem que estão subindo e não descendo, mas elas estão realmente descendo.

spookylittlepickle: UFO: April 27, 1995 - Bogadinski,...

TadeuNow that everyone has got a full HD camera in their pockets, where are all the UFOs in full HD resolution? :S

Newswire: Facebook tinkered with users’ feeds for a massive psychology experiment

TadeuImagina na copa

Scientists at Facebook have published a paper showing that they manipulated the content seen by more than 600,000 users in an attempt to determine whether this would affect their emotional state. The paper, “Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks,” was published in The Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences. It shows how Facebook data scientists tweaked the algorithm that determines which posts appear on users’ news feeds—specifically, researchers skewed the number of positive or negative terms seen by randomly selected users. Facebook then analyzed the future postings of those users over the course of a week to see if people responded with increased positivity or negativity of their own, thus answering the question of whether emotional states can be transmitted across a social network. Result: They can! Which is great news for Facebook data scientists hoping to prove a point about modern psychology. It ...