Heat death held a morbid fascination for Victorian-era physicists. It was an early example of how everyday physics connects to the grandest themes in cosmology. Drop ice cubes into a glass of water, and you create a situation that is out of equilibrium. The ice melts, the liquid chills, and the system reaches a common temperature. Although motion does not cease — water molecules continue to...

Shared posts

Rain Szeto Renders Imaginitive Scenarios in Intricately Detailed Ink and Watercolor Illustrations

“Cat Hours.” All images © Rain Szeto, shared with permission

In Rain Szeto’s intricately rendered fictional universe, people partake in work and pastimes surrounded by stacks of books, snacks, merchandise, and mementos. Her detailed illustrations (previously) portray the organized chaos of everyday activities in domestic spaces and in shops, cafes, and outdoor areas. Typically centered around a single character like a baker behind a counter or a figure carrying a pot of flowers, the scenes are filled with with quotidian objects, providing a lived-in feeling that brims with colorful energy.

Based in San Francisco, Szeto began working in comics during art school, which cemented her interest in narrative drawings. Specific details like the design of food packaging, an elaborate audio mixer setup, or pastries in a glass case suggest individual hobbies, jobs, and personalities distinctive enough that they could be mistaken for real places. Many of her recent pieces also feature feline friends that stride by confidently or curl up on cushions, including an orange tabby that could just as well be making the rounds to all of the inviting spaces.

Most of these works are on view through April 26 in Szeto’s solo exhibition Idle Moments Too at Giant Robot’s GR2 location in Los Angeles. Find more of her work on Instagram.

“Loaves”

“Afternoon Movie”

“Checked Out”

Left: “Lunch Break.” Right: “Springtime”

“Corner Shop”

“First Customer”

“Noodlin'”

“Shop Cat”

“Smoked Fish”

“Summer Waves”

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. The article Rain Szeto Renders Imaginitive Scenarios in Intricately Detailed Ink and Watercolor Illustrations appeared first on Colossal.

A Custom 3D Printer Weaves Two Colors of Clay into Elaborately Textured Sculptures

All photos by Matt Dayak, © Brian Peters, shared with permission

Through his innovative Dyadic Series, artist and designer Brian Peters defies the limits of clay and technologies. The collection is comprised of cylindrical sculptures that expertly weave soft blue and green with the natural color of ceramic, all created with a custom 3D printer.

Rather than achieve the two-toned compositions through glazes or paints, Peters coded the machine to fabricate each sculpture with both the pigmented and raw materials—most 3D printers add layers from a single body of wet clay—and the resulting forms elegantly entwine unique, textured patterns.

Born out of more than a decade of research into ceramics and the fabrication process, the series is proof that more variations in this technology are possible. Peters shares:

The idea of printing in two (or more) colors simultaneously has been something that has intrigued me for a while, and I finally developed the expertise in building 3D printers to pursue the idea. This new field of exploration is very exciting because you are able to directly print with color, rather than glazing the color afterwards, and will allow me to explore different patterns and textures (such as the woven-like texture created with this first collection).

Based in Pittsburgh, Peters frequently works on large-scale architectural works and wall sculptures, which you can find on his site. He’s currently in the midst of several commissions and building another 3D printer with new capabilities, so follow him on Instagram for updates. (via Design Milk)

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. The article A Custom 3D Printer Weaves Two Colors of Clay into Elaborately Textured Sculptures appeared first on Colossal.

Wealth of Nature

How has Costa Rica managed to restore its natural wonders, while big, rich nations fail?

By George Monbiot, published in the Guardian 21st April 2023

One of the world’s greatest environmental heroes doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page. Though he has done more to protect the living planet than almost anyone alive, his name is scarcely known. It’s partly because he’s quiet and self-effacing and partly because of a general ignorance about Central America that so few of us have heard of Alvaro Umaña.

This might be about to change. He stars in a fascinating film, now released in the Netherlands and negotiating global sales, called Paved Paradise (disclosure: I was also interviewed). It’s the first feature-length documentary I’ve watched that engages intelligently with the most critical environmental issue: land use. By contrast with popular but misguided films such as Kiss the Ground or The Biggest Little Farm, it recognises that sprawling extractive land uses are a lethal threat to the living world. It makes the case that, unless we count the hectares and decide together how best they should be used, we will lose the struggle to defend the habitable planet.

Paved Paradise tells the story of the most remarkable ecological turnaround on Earth: the transformation of Costa Rica. From 1986 to 1990, Umaña was environment minister in Óscar Arias’s government. Arias received the Nobel peace prize for his regional diplomacy. But the equally astonishing environmental shift Umaña catalysed is less well known.

Until the Arias government took power, Costa Rica suffered one of the world’s worst deforestation rates: on one scientific assessment, its forest cover fell to just 24.4% of the country.

Today, forests occupy 57%, which, Umaña tells me, is close to the maximum: some parts were never forested, while others are now occupied by productive farms and cities. While a small amount of illegal timber felling continues, Costa Rica is the only tropical country to have more or less stopped and then reversed deforestation. It now has one of the world’s highest percentages of protected areas. How did it happen?

Umaña persuaded Arias to let him run a new department (energy and environment) with responsibility for protected areas. He saw that the key task was to change financial incentives. Though cattle ranching was unproductive, as the land could support just one cow per hectare, it was marginally more lucrative than allowing the forest to stand.

His department calculated the opportunity cost of forgoing a cow at $64 a year, so this was the money it offered for protecting or restoring a hectare of forest. He began by reaching out to small farmers and their representatives, in those regions where people were most sympathetic to the idea. The smallest landholders were offered grants, slightly larger ones were offered soft loans, with the promise that if their forest was still standing after five years, it could serve as the loan’s guarantee. The plan was astonishingly successful: 97% of those who received loans protected or restored the trees on their land. As landholders everywhere saw the scheme made financial sense, it became massively oversubscribed.

Needing more money, in 1988 Umaña agreed a debt-for-nature swap with the Dutch government. It would cancel part of the foreign debt if the money Costa Rica would otherwise have spent on servicing it were used instead for forest conservation.

Following a change of government, Umaña became the country’s climate ambassador. He helped introduce a special tax of 3.5% on fossil fuels to help pay for forest conservation.

Soon the tree protectors began to supplement their income. Tourists are now the country’s second-biggest source of revenue: government figures show that 65% of them list ecotourism as a principal reason for visiting. They come to see toucans, green macaws, howler monkeys, jaguars, caimans, poison dart frogs and other resurgent natural wonders. Landholders can also apply for a licence selectively to fell a small number of their trees, some of which are very valuable.

One reason for the programme’s success is its sharing of financial benefits, especially through its world-leading gender action plan. Another is cultural change. In building a new identity around “la pura vida” (the simple life), the government showed that, in combination with economic incentives, national pride can help bring long-established practices such as forest clearance for cattle ranching to an end.

Costa Rica helped to inspire the Bonn Challenge, a global programme to restore degraded and deforested land. It launched the international plan to protect 30% of the planet by 2030, and was one of the two founder members, in 2021, of the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (though it has since stood back, following a change of government). These are astonishing achievements for a tiny country.

Compare this record with policy in the UK, which, 37 years after Umaña set to work, is still pissing about with half-solutions and non-solutions, held to ransom by rich and powerful property owners and entirely incapable of making strategic environmental decisions, especially on land use. While Costa Rica’s wildlife is booming, ours is in freefall. The government seems determined, against all advice, to allow this disastrous trend to continue for the rest of the decade.

As for the fuel taxes that could have been used, like Costa Rica’s, to fund ecological repair, the UK government has now forgone a cumulative £80bn in revenue by both abandoning Labour’s fuel duty escalator and giving motorists a special rebate. As a result, our carbon emissions are up to 7% higher than they would otherwise have been.

So why does a rich, powerful nation fail, while a small, much poorer one succeeds? Talking to Umaña and researching the history of this transformation suggests a simple answer: quality of government. When governments are committed, decisive and consistent, things happen. When they are beholden to lobby groups, cronyism and corruption, and delegate responsibility to an abstraction called “the market”, they spend decades flapping their hands while chaos reigns.

Our self-hating state, which parades its can’t-do culture as a source of pride, insisting that government cannot and should not solve our problems, is constitutionally destined to founder. Why can’t we follow Costa Rica’s example? Because a small but powerful contingent insists on failure.

www.monbiot.com

One year in, the devastating environmental impact of war in Ukraine comes into view

February marked the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, 12 months of humanitarian, political, and economic crises. Tens of thousands of lives have been lost, millions of people have been displaced, and while the Ukrainian military surprised the world by holding its own and reclaiming half the land captured by Russia this year, the fighting has no clear end in sight.

The conflict also put the global oil trade in the spotlight. From the beginning, some argued that spiking gas prices in the absence of Russian fuel supplies would spur clean energy planning in Europe and elsewhere. But a year out, it has become clear that the war resulted in essentially a doubling down on dirty fuel, at least in the short term. European subsidies for fossil fuels rose higher than ever and carbon emissions reached a global peak as countries scrambled for coal, oil, and gas. Nations that couldn’t afford natural gas turned to burning more coal, and U.S. President Joe Biden called for more domestic fossil fuel production. Meanwhile, Shell, Exxon, and BP reported record profits.

Largely ignored, however, at least in many international circles, has been the war’s massive environmental impact on Ukraine itself. A year out, the extent of these damages are becoming clear. In its campaign, Russia has targeted electric grids, oil refineries, and nuclear plants, and wrought untold damage to ecosystems, soil, and water through the bombing of fields and industrial sites.

“In 2015, we had a fire at an oil facility that was one of the biggest environmental disasters in Ukrainian history,” said Yevheniia Zasiadko, the head of the climate department at Ecoaction, a Ukrainian nonprofit. “Since the Russians invaded, there have been more than 40 such facilities destroyed across Ukraine.”

Attacks on oil depots caused some of the tens of thousands of blazes that have burned across Ukraine mostly started by shelling. About a third of the country’s forests have been affected, and over 57,000 acres have completely burned down, according to data from Ukraine’s environment ministry (as reported in the Economist, the ministry’s website was down at publication time). Oil and trees set ablaze are some of the main contributors to the 46.2 million tons of carbon dioxide, or CO2, released into the atmosphere since Russia’s invasion. The ministry says air pollution has been one of the war’s most costly environmental impacts.

Ecoaction has been tracking the environmental damage since last February, drawing information from media reports and local government announcements and publishing updated findings online every two weeks. Greenpeace joined the effort to provide satellite verification and mapping. So far the team has documented 863 instances of degradation, including widespread forest fires, destroyed terrestrial and marine ecosystems, burst pipelines filling wetlands with oil, sunken ships in the Black Sea, chemical plant waste spilling into rivers, and radioactive releases from nuclear plants. “A huge territory is still occupied so we don’t even know what is happening there,” said Zasiadko. Much of the liberated territory of Ukraine is full of explosive mines, which poses a challenge for mapping and ground-truthing.

“Ukraine is an industrial country and we have a lot of chemical and heavy metal [processing] factories,” said Zasiadko. A big part of that was destroyed, she said, which released toxic materials to flow into waterways and leach into the soil. In the early days of the war, part of a Russian missile hit a livestock waste storage facility near the Ikva river in the Rivne region of western Ukraine and caused a fish die-off in the neighboring region. In another case near the town of Sumy, in northeast Ukraine, people had to stay inside their homes for days after receiving notice of ammonia leaking from a struck power plant.

“Because lots of area was mined [with explosive devices], firefighters cannot do their job, and local scientists cannot go in to monitor the situation.”

Kateryna Polyanska, an ecologist with the Ukrainian environmental nonprofit Environment People Law, has been traveling around the country examining the landscape and taking soil samples from mine craters. “At the beginning I tried to analyze satellite images but that wasn’t enough,” she told Grist. “I understood that I should go to the fields.” Her early lab results have found nickel, zinc, and other heavy metals from shells, bombs, and shrapnel in the soil, as well as chemical contamination and fuel from unexploded missiles. In her travels, she also observed the growing problem of “war waste,” toxic materials from rubble, like asbestos in home ceilings, without any place for proper disposal.

“A lot of these things have a huge risk for human health and lives,” said Polyanska, adding that the attacks and their aftereffects have also impacted animals, like foxes in the forest, dolphins in the Black Sea, and rare ecosystems like the Holy Mountains in the Donetsk province, in the east of Ukraine. Over 30 percent of the country’s natural protected areas have been hit and the environment ministry estimates 600 animal species and 880 plant species are at risk of extinction, as reported in the Guardian.

Another area of particular concern has been nuclear radiation. Last February and March, Russian forces occupied the Chernobyl power station, the site of an infamous 1986 nuclear accident, for five weeks; they dug trenches in the thousand-square-mile radioactive exclusion zone, now effectively a protected area. Studies after they left showed radiation levels three times higher than normal in parts of the Red Forest.

“Because lots of area was mined [meaning scattered with explosive devices], firefighters cannot do their job, and local scientists cannot go in to monitor the situation,” said Denys Tsutsaiev, a Greenpeace campaigner in Kyiv. He added that just after the liberation of the Chernobyl territory, a fire truck drove over a mine and exploded.

Ukraine’s four active nuclear plants from which the country sources half its electricity are also at risk. For the past eleven months, Russian forces have occupied the Zaporizhzhia plant in the south of the country, and damages to surrounding power supply lines raise concerns about reactors overheating. “At the moment there is only one backup line connected to the plant,” said Tsutsaiev. Russians have also drained the nearby Kakhovka reservoir, used for cooling the plant’s reactors and providing water to large populations to the south.

Donbas, the country’s eastern region where much of its industry is concentrated, is also the country’s main coal producing area. It has long been a site of conflict, proclaimed partially as an independent territory by pro-Russian separatists in 2014 and currently under Russian occupation. Between 2015 and 2021, international monitoring showed that over 30 coal mines had been flooded in the region, polluting groundwater and surface water with metals, sulfates, and mineral salts. Since the beginning of full-scale invasion, 10 more have been flooded, though it’s possible that the actual number is higher.

“Usually when Russia occupies a territory they cut off electricity,” said Zasiadko. “That means the pipelines aren’t taking out groundwater, and the mines flood.”

While much of Ukraine’s power grid miraculously remains standing, over 213 reported attacks on electric facilities over the last several months have left large parts of the country without power, limiting drinking water treatment and compromising human health.

With war still raging, Zasiadko says it has been hard to get Ukrainian officials and international allies to pay attention to reconstruction in liberated areas. Harder still is drawing resources for environmental restoration.

“Ukrainian authorities are speaking about ecocide but there isn’t much action on ‘what are we going to do with the pollutants?’,” said Zasiadko. “There is mostly discussion about rebuilding infrastructure and roads.” In July, at the Ukraine Recovery Conference in Lugano, Switzerland, Ukrainian authorities presented their first reconstruction plan to a large group of international leaders and finance institutions; environmental groups objected to it on the grounds that it consisted mostly of construction projects “without a systematic approach to nature conservation.”

Zasiadko says the priority, when it comes to the environment, needs to be testing, monitoring, and pollution clean-up. Ukraine’s economy is 40 percent agriculture, she said, and it’s already coming back in the reclaimed areas. “At the moment the soil is not always de-mined and there have been many examples of explosions on farmlands.” She is concerned that people are growing food in polluted soil. Soil cleanup is a long endeavor, specific to the site and the contaminant. And de-mining could take 10 years. “In the future, we will need special divers who can go in and clean the rivers from explosive materials and mines,” said Polyanska.

Ukraine’s environment ministry, for its part, is keeping an extensive record of the environmental damage and evaluating the cost with the goal of demanding compensation from Russia. The ministry’s most recent findings report that almost a third of the country remains hazardous, 160 nature reserves are under threat of destruction, and the total cost of environmental damage is over $50 billion. While Tsutsaiev appreciates the efforts to document the damage, he says the government and partners should also be seeking other funding and making a plan for how restoration is going to occur.

Ukraine was in the midst of a “just transition” pilot program to help coal workers find new clean energy jobs in nine cities in the eastern coal mining regions when the war broke out. That project has been put on hold. Tsutsaiev hopes reconstruction can be used as an opportunity to rebuild with climate change in mind.

“Greening the reconstruction means empowering local municipalities not to use all the old technologies but to think about energy independence and energy security,” said Tsutsaiev. He cited the example of a hospital close to Kyiv that was damaged in the first days of the war. Greenpeace helped with the installation of a heat pump and solar panels during reconstruction. “Now, when there is no electricity in the area, the hospital continues to receive power,” he said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline One year in, the toxic legacy of war in Ukraine comes into view on Mar 1, 2023.

A Wooden Artwork Miraculously Unfurls into a Functional Desk Designed by Robert van Embricqs

All images courtesy of Robert van Embricqs

The surge in remote work during the last few years prompted Amsterdam-based designer Robert van Embricqs to rethink how conventional desks would impact a home’s atmosphere. He wanted to invite “the user to fold that desk away when work is over” and created a now-viral piece that seamlessly transforms from office to artwork.

Constructed with warm wood and brass hinges, the “Flow Wall Desk” features flush vertical slats that twist and unfold into a tabletop. The small piece of furniture, which can support about 40 pounds, is minimal in aesthetic and mimics organic movements as it unfurls from sleek relief to functional space.

Find the desk and other modular designs in van Embricqs’ shop, and follow his work on Instagram. (via Hyperallergic)

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. The article A Wooden Artwork Miraculously Unfurls into a Functional Desk Designed by Robert van Embricqs appeared first on Colossal.

While Vermeer’s ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ Is on Loan, the Mauritshuis Showcases 170 Imaginative Renditions in Its Place

Ankie Gooijers. All images courtesy of the Mauritshuis

While Johannes Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring” is on loan to Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum for the largest-ever exhibition of the Dutch artist’s work, a cheeky surrogate takes its place. The Mauritshuis in the Hague is currently showing My Girl with a Pearl, a lighthearted and vastly creative digital installation, where the iconic painting usually resides.

Resulting from an open call last year that garnered nearly 3,500 submissions, the temporary piece features 170 renditions of Vermeer’s 1655 portrait presented on a loop. Mediums and styles vary widely, and the installation features everything from an abstract iteration using multi-color rubber bands to elegantly photographed portraiture to the viral corn-cob figure.

My Girl with a Pearl is on view through April 1 when the original painting—which has been the site of speculation in recent weeks as scholars revealed the earring to be an imitation—is slated to return to the Hague. Those who won’t be able to see the installation in person can find dozens of the renditions on Instagram, in addition to a virtual exhibition of the Vermeer exhibition on the Rijksmuseum’s site.

Lab 07

Guus the Duck

Nanan Kang

Ege Islekel

Emil Schwärzler

Left: Kathy Clemente. Right: Rick Rojnic

Caroline Sikkenk

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. The article While Vermeer’s ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ Is on Loan, the Mauritshuis Showcases 170 Imaginative Renditions in Its Place appeared first on Colossal.

The 2022 World Nature Photography Awards Vacillate Between the Humor and Brutality of Life on Earth

Photo © Staffan Widstrand. All images courtesy of World Nature Photography Awards, shared with permission

Moments of coincidental humor, stark cruelty, and surprising inter-species intimacies are on full display in this year’s World Nature Photography Awards. The winners of the 2022 competition encompass a vast array of life across six continents, from an elephant’s endearing attempt at camouflage to a crocodile covered in excessively dry mud spurred by drought. While many of the photos highlight natural occurrences, others spotlight the profound impacts humans have on the environment to particularly disastrous results, including Nicolas Remy’s heartbreaking image that shows an Australian fur seal sliced open by a boat propellor.

Find some of the winning photos below, and explore the entire collection on the contest’s site.

Photo © Jens Cullmann, gold winner and grand prize of the World Nature Photographer of the Year

Photo © Norihiro Ikuma

Photo © Julie Kenny

Photo © Nicolas Remy

Photo © Vladislav Tasev

Photo © Tamas Aranyossy

Photo © Dr Artur Stankiewicz

Photo © Takuya Ishiguro

Photo © Thomas Vijayan

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. The article The 2022 World Nature Photography Awards Vacillate Between the Humor and Brutality of Life on Earth appeared first on Colossal.

A looming El Niño could give us a preview of life at 1.5C of warming

The last three years were objectively hot, numbering among the warmest since records began in 1880. But the scorch factor of recent years was actually tempered by a climate pattern that slightly cools the globe, “La Niña.”

This year and next, La Niña might give way to its hotter counterpart, El Niño. Distinguished by warm surface waters in the tropical Pacific Ocean, the weather pattern has consequences for temperatures, drought, and rainfall around the world. The planet hasn’t seen a strong El Niño since 2016 — the hottest year ever recorded — and the next El Niño will occur on top of all the warming that’s occurred since then.

El Niño’s return could further strain sensitive ecosystems, like the Great Barrier Reef and the Amazon rainforest, and nudge the planet closer to worrisome tipping points. It might also push the world past a threshold that scientists have been warning about, giving people a temporary glimpse of what it’s like to live on a planet that’s 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) than preindustrial times — a level that could begin to unleash some of the more drastic consequences of climate change.

“Looking back at past years when you’ve had El Niños, we have seen those global temperatures kind of boost themselves, sometimes significantly, depending on how big El Niño was,” said Tom Di Liberto, a climate scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

El Niño is expected to arrive later this year, and the warmer weather pattern could continue to build up through 2024, sending global temperatures past that 1.5 degrees C marker, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, after which they could ease back when a La Niña returns. But there’s still plenty of uncertainty. According to the most recent forecast from NOAA, El Niño has a 60 percent chance of forming by the fall, although other scientists are more confident it’s on the way. Researchers in Germany and China, some of whom issued an early warning for the El Niño that began in 2015, have predicted an 89 percent chance that the pattern will emerge this year — and have cautioned that it could be a strong one.

The world has already warmed an average of 1.2 degrees C (2.2 degrees F) since the Industrial Revolution ushered in the widespread use of fossil fuels. Most estimates said 1.5 degrees of warming wouldn’t arrive until at least the early 2030s. The chance that El Niño could push the planet above that mark for the first time, however, has about a 50/50 chance of happening in the next five years, Adam Scaife, the head of long-range prediction at the U.K. Met Office, told the Guardian last month.

1.5 degrees is about the level of warming that scientists say would be more likely to start setting off irreversible feedback loops, such as the disintegration of ice sheets in Greenland and the West Antarctic, the abrupt thawing of permafrost in the Arctic, or the collapse of the Atlantic Ocean’s Gulf Stream current (as imagined in the film The Day After Tomorrow). Island nations have spearheaded the effort to keep global temperatures below 1.5 degrees because it’s a matter of survival for low-lying atolls that could be swallowed up by rising ocean waters. When crafting the Paris Agreement in 2015, countries committed to “pursuing efforts” to limit warming to 1.5 degrees. In the spirit of taking the goal more seriously, diplomats asked the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to release a report on the effects of 1.5 degrees.

When the report came out in 2018, it made a splash, with news headlines warning that the world had “12 years” left to tackle climate change. Activists, including Greta Thunberg, rallied around the goal as a point of no return. But as time wore on and the world failed to dramatically rein in carbon emissions, the target — already considered unrealistic back in 2018 — slid out of reach. Scientists say that it’s certainly bad news, but it’s not game over. “It’s not like there’s a magical barrier at that number in terms of like, we can never go back, or like it’s a clear tipping point where that number specifically flips a switch,” Di Liberto said. “These things run on a spectrum.” Each incremental increase in warming leads to more catastrophic consequences.

Hitting 1.5 degrees in an El Niño year wouldn’t be the same as averaging those temperatures across several years. “This would be a temporary breaching,” said Josef Ludescher, a scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. “This is a different story compared to if it’s a constant state every year for vegetation or corals. One year might be survivable, but what happens if it’s always those temperatures?”

That said, a strong El Niño like the one in that started in 2015 could cause some permanent damage. That year, the Great Barrier Reef in Australia saw the most devastating coral bleaching event in history, with a marine heat wave killing off more than half of corals in the northern part of the reef. If El Niño appears again, “that would ratchet up concerns, especially for another bleaching event across the Great Barrier Reef,” Di Liberto said. Even La Niña years, such as last year, are getting hot enough to cause mass bleaching.

El Niño’s arrival could also be disastrous for the Amazon rainforest, which scientists have warned is nearing a critical “tipping point.” The rainforest, already struggling with challenges from climate change and deforestation, could eventually transform into something more like a grassy savanna, releasing the vast stores of carbon held in its trees. The drought and fires egged on by the last strong El Niño killed roughly 2.5 billion trees in the Amazon, temporarily turning one of the world’s largest carbon-capturing ecosystems into a giant source of carbon emissions.

That same El Niño brought drought to Indonesia, and wildfires took off in forests and peatlands. During their height in September and October that year, the fires in Indonesia and surrounding areas released vast stores of carbon into the atmosphere per day — by one estimate, more than the entire European Union emitted from burning fossil fuels over the same period.

And, just like any other year, ice that melts from the land into the ocean helps lift sea levels. The last big El Niño was likely behind a major bout of melting in Antarctica in January 2016, when a sheet of meltwater developed across the surface of the Ross Ice Shelf, affecting an area larger than the state of Texas. Stronger El Niños may also accelerate the melting of the Antarctic ice sheet by warming up the deep waters of the ice shelf, according to a study by Australian researchers published this week in the journal Nature Climate Change.

But every El Niño is its own thing. Di Liberto likes to talk about it as a “tilt in the odds” towards different weather events. El Niño “may be the most consistent thing that allows us to forecast farther in advance, but we know there are other climate phenomena which could be just as strong an influence in a given month or season,” he said.

The effects would vary, depending on the place. In the United States, for instance, El Niño would likely bring more rain to the South and drier conditions to northern states. It would also cool waters in the Atlantic and lead to stronger wind shear that could tear apart tropical storms, a promising sign for a quieter hurricane season.

Climate change may even be starting to affect El Niño itself, leading to “super El Ninos.” Over the last 40 years or so, the world has seen some of the strongest El Niños on record, Ludescher said. But it’s not totally clear whether this is a trend or just plain old chance. In any case, most models forecast that the world will continue to see intense El Niños over the next century — a worrying sign that the hottest years to come will be made even hotter.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A looming El Niño could give us a preview of life at 1.5C of warming on Feb 24, 2023.

This “climate-friendly” fuel comes with an astronomical cancer risk

This story was originally published by ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for their newsletter.

The Environmental Protection Agency recently gave a Chevron refinery the green light to create fuel from discarded plastics as part of a “climate-friendly” initiative to boost alternatives to petroleum. But, according to agency records obtained by ProPublica and the Guardian, the production of one of the fuels could emit air pollution that is so toxic, 1 out of 4 people exposed to it over a lifetime could get cancer.

“That kind of risk is obscene,” said Linda Birnbaum, former head of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. “You can’t let that get out.”

That risk is 250,000 times greater than the level usually considered acceptable by the EPA division that approves new chemicals. Chevron hasn’t started making this jet fuel yet, the EPA said. When the company does, the cancer burden will disproportionately fall on people who have low incomes and are Black because of the population that lives within 3 miles of the refinery in Pascagoula, Mississippi.

ProPublica and the Guardian asked Maria Doa, a scientist who worked at the EPA for 30 years, to review the document laying out the risk. Doa, who once ran the division that managed the risks posed by chemicals, was so alarmed by the cancer threat that she initially assumed it was a typographical error. “EPA should not allow these risks in Pascagoula or anywhere,” said Doa, who now is the senior director of chemical policy at Environmental Defense Fund.

In response to questions from ProPublica and the Guardian, an EPA spokesperson wrote that the agency’s lifetime cancer risk calculation is “a very conservative estimate with ‘high uncertainty,’” meaning the government erred on the side of caution in calculating such a high risk.

Under federal law, the EPA can’t approve new chemicals with serious health or environmental risks unless it comes up with ways to minimize the dangers. And if the EPA is unsure, the law allows the agency to order lab testing that would clarify the potential health and environmental harms. In the case of these new plastic-based fuels, the agency didn’t do either of those things. In approving the jet fuel, the EPA didn’t require any lab tests, air monitoring, or controls that would reduce the release of the cancer-causing pollutants or people’s exposure to them.

In January 2022, the EPA announced the initiative to streamline the approval of petroleum alternatives in what a press release called “part of the Biden-Harris Administration’s actions to confront the climate crisis.” While the program cleared new fuels made from plants, it also signed off on fuels made from plastics even though they themselves are petroleum-based and contribute to the release of planet-warming greenhouse gases.

Although there’s no mention of discarded plastics in the press release or on the EPA website’s description of the program, an agency spokesperson told ProPublica and the Guardian that it allows them because the initiative also covers fuels made from waste. The spokesperson said that 16 of the 34 fuels the program approved so far are made from waste. She would not say how many of those are made from plastic and stated that such information was confidential.

All of the waste-based fuels are the subject of consent orders, documents the EPA issues when it finds that new chemicals or mixtures may pose an “unreasonable risk” to human health or the environment. The documents specify those risks and the agency’s instructions for mitigating them.

But the agency won’t turn over these records or reveal information about the waste-based fuels, even their names and chemical structures. Without those basic details, it’s nearly impossible to determine which of the thousands of consent orders on the EPA website apply to this program. In keeping this information secret, the EPA cited a legal provision that allows companies to claim as confidential any information that would give their competitors an advantage in the marketplace.

Nevertheless, ProPublica and the Guardian did obtain one consent order that covers a dozen Chevron fuels made from plastics that were reviewed under the program. Although the EPA had blacked out sections, including the chemicals’ names, that document showed that the fuels that Chevron plans to make at its Pascagoula refinery present serious health risks, including developmental problems in children and cancer and harm to the nervous system, reproductive system, liver, kidney, blood and spleen.

Aside from the chemical that carries a 25 percent lifetime risk of cancer from smokestack emissions, another of the Chevron fuels ushered in through the program is expected to cause 1.2 cancers in 10,000 people — also far higher than the agency allows for the general population. The EPA division that screens new chemicals typically limits cancer risk from a single air pollutant to 1 case of cancer in a million people. The agency also calculated that air pollution from one of the fuels is expected to cause 7.1 cancers in every 1,000 workers — more than 70 times the level EPA’s new chemicals division usually considers acceptable for workers.

In addition to the chemicals released through the creation of fuels from plastics, the people living near the Chevron refinery are exposed to an array of other cancer-causing pollutants, as ProPublica reported in 2021. In that series, which mapped excess cancer risk from lifetime exposure to air pollution across the U.S., the highest chance was 1 cancer in 53 people, in Port Arthur, Texas.

The one-in-four lifetime cancer risk from breathing the emissions from the Chevron jet fuel is higher even than the lifetime risk of lung cancer for current smokers.

In an email, Chevron spokesperson Ross Allen wrote: “It is incorrect to say there is a one-in-four cancer risk from smokestack emissions. I urge you avoid suggesting otherwise.” Asked to clarify what exactly was wrong, Allen wrote that Chevron disagrees with ProPublica and the Guardian’s “characterization of language in the EPA Consent Order.” That document, signed by a Chevron manager at its refinery in Pascagoula, quantified the lifetime cancer risk from the inhalation of smokestack air as 2.5 cancers in 10 people, which can also be stated as one in four.

In a subsequent phone call, Allen said: “We do take care of our communities, our workers and the environment generally. This is job one for Chevron.”

In a separate written statement, Chevron said it followed the EPA’s process under the Toxic Substances Control Act: “The TSCA process is an important first step to identify risks and if EPA identifies unreasonable risk, it can limit or prohibit manufacture, processing or distribution in commerce during applicable review period.”

The Chevron statement also said: “Other environmental regulations and permitting processes govern air, water and handling hazardous materials. Regulations under the Clean Water, Clean Air and Resource Conservation and Recovery Acts also apply and protect the environment and the health and safety of our communities and workers.”

Similarly, the EPA said that other federal laws and requirements might reduce the risk posed by the pollution, including Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s regulations for worker protection, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act and rules that apply to refineries.

But OSHA has warned the public not to rely on its outdated chemical standards. The refinery rule calls for air monitoring only for one pollutant: benzene. The Clean Water Act does not address air pollution. And the new fuels are not regulated under the Clean Air Act, which applies to a specific list of pollutants. Nor can states monitor for the carcinogenic new fuels without knowing their names and chemical structures.

We asked Scott Throwe, an air pollution specialist who worked at the EPA for 30 years, how existing regulations could protect people in this instance. Now an independent environmental consultant, Throwe said the existing testing and monitoring requirements for refineries couldn’t capture the pollution from these new plastic-based fuels because the rules were written before these chemicals existed. There is a chance that equipment designed to limit the release of other pollutants may incidentally capture some of the emissions from the new fuels, he said. But there’s no way to know whether that is happening.

Under federal law, companies have to apply to the EPA for permission to introduce new chemicals or mixtures. But manufacturers don’t have to supply any data showing their products are safe. So the EPA usually relies on studies of similar chemicals to anticipate health effects. In this case, the EPA used a mixture of chemicals made from crude oil to gauge the risks posed by the new plastic-based fuels. Chevron told the EPA the chemical components of its new fuel but didn’t give the precise proportions. So the EPA had to make some assumptions, for instance that people absorb 100 percent of the pollution emitted.

Asked why it didn’t require tests to clarify the risks, a spokesperson wrote that the “EPA does not believe these additional test results would change the risks identified nor the unreasonable risks finding.”

In her three decades at the EPA, Doa had never seen a chemical with that high a cancer risk that the agency allowed to be released into a community without restrictions.

“The only requirement seems to be just to use the chemicals as fuel and have the workers wear gloves,” she said.

While companies have made fuels from discarded plastics before, this EPA program gives them the same administrative break that renewable fuels receive: a dedicated EPA team that combines the usual six regulatory assessments into a single report.

The irony is that Congress created the Renewable Fuel Standard Program, which this initiative was meant to support, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and boost the production of renewable fuels. Truly renewable energy sources can be regenerated in a short period of time, such as plants or algae. While there is significant debate about whether ethanol, which is made from corn, and other plant-based renewable fuels are really better for the environment than fossil fuels, there is no question that plastics are not renewable and that their production and conversion into fuel releases climate-harming pollution.

Under the EPA’s Renewable Fuel Standard, biobased fuels must meet specific criteria related to their biological origin as well as the amount they reduce greenhouse gas emissions compared with petroleum-based fuels. But under this new approach, fuels made from waste don’t have to meet those targets, the agency said.

In its written statement, Chevron said that “plastics are an essential part of modern life and plastic waste should not end up in unintended places in the environment. We are taking steps to address plastic waste and support a circular economy in which post-use plastic is recycled, reused or repurposed.”

But environmentalists say such claims are just greenwashing.

Whatever you call it, the creation of fuel from plastic is in some ways worse for the climate than simply making it directly from fossil fuels. Over 99% of all plastic is derived from fossil fuels, including coal, oil and gas. To produce fuel from plastics, additional fossil fuels are used to generate the heat that converts them into petrochemicals that can be used as fuel.

“It adds an extra step,” said Veena Singla, a senior scientist at NRDC. “They have to burn a lot of stuff to power the process that transforms the plastic.”

Less than 6 percent of plastic is recycled in the U.S. Much of the rest — hundreds of millions of tons of it — is dumped in the oceans each year, killing marine mammals and polluting the world. Plastic does not fully decompose; instead it eventually breaks down into tiny bits, some of which wind up inside our bodies. As the public’s awareness of the health and environmental harm grows, the plastics industry has found itself under increasing pressure to find a use for the waste.

The idea of creating fuel from plastic offers the comforting sense that plastics are sustainable. But the release of cancer-causing pollution is just one of several significant problems that have plagued attempts to convert discarded plastic into new things. One recent study by scientists from the Department of Energy found that the economic and environmental costs of turning old plastic into new using a process called pyrolysis were 10 to 100 times higher than those of making new plastics from fossil fuels. The lead author said similar issues plague the use of this process to create fuels from plastics.

Chevron buys oil that another company extracts from discarded plastics through pyrolysis. Though the parts of the consent order that aren’t blacked out don’t mention that this oil came from waste plastics, a related EPA record makes this clear. The cancer risks come from the pollution emitted from Chevron’s smokestacks when the company turns that oil into fuel.

The EPA attributed its decision to embark on the streamlined program in part to its budget, which it says has been “essentially flat for the last six years.” The EPA spokesperson said that the agency “has been working to streamline its new chemicals work wherever possible.”

The New Chemicals Division, which houses the program, has been under particular pressure because updates to the chemicals law gave it additional responsibilities and faster timetables. That division of the agency is also the subject of an ongoing EPA Inspector General investigation into whistleblowers’ allegations of corruption and industry influence over the chemical approval process.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline This “climate-friendly” fuel comes with an astronomical cancer risk on Feb 25, 2023.

Bird Chef

The post Bird Chef appeared first on The Perry Bible Fellowship.

Yes, Crypto is ALL a Scam

TimBThis guy can't NOT put a brick on the accelerator. Still, the comparison between crypto and indulgences is pretty fun

Yes, Crypto is ALL a Scam

Every day I write something about crypto to the nature of “crypto is all a scam”; this belief represents the core of my philosophy in understanding the complexities of crypto—in fact, it’s the very first line of my book on the subject. I sometimes get pushback (mostly in bad faith) on this as being hyperbolic, but the reality is that it’s not hyperbolic at all. It’s the only defensible position once one dives into the underlying ecaonomics of the products being sold, which are all contingent on fraud and misrepresentation, albeit of different forms. From a pure definitional perspective, the Oxford dictionary defines a scam as:

scam /skæm/ (noun): a clever and dishonest plan for making money

And indeed, crypto does match that definition to a tee; it is equal parts clever and dishonest, and misrepresentation and the abuse of language are absolutely central to this scheme. Nevertheless, crypto is undoubtedly both a clever and ingenious scam, and I say this with complete sincerity. It’s not often in history that you get to witness a new predatory financial scheme arise, and with crypto, we got a first-hand look at a genuinely new form of crime rooted in a particularly pernicious and intellectually convoluted duplicity. Crypto is not a currency. Crypto is useless as a unit of account. Crypto is not a reliable store of value. Crypto is not a hedge against inflation. Crypto is not a medium of exchange. Crypto is not a new financial system. Crypto is not a new internet.

These cases are straightforward. If someone sells something that is not what they claim it is, they’re either dishonest in directly misrepresenting the product or themselves. If you sell a horse as a car, you’re either lying or can’t tell the difference between the two and thus have no business selling either, and in both cases, this is a scam. Sincerely believing a car is identical to a horse does not alter objective reality. Similarly, the “crypto as currency” and “crypto as investment” narratives have been thoroughly debunked because the truth value of these statements is predicated on factual claims that are demonstrably falsifiable. The only defensible narratives that remain are slightly fuzzier concepts where crypto is one of:

- A collectible like trainers or art

- A gambling contract

Collectibles

For collectibles, the topic is nuanced and largely philosophical. People assign value to all manner of bizarre curio. However, in most cases, these things have intrinsic value arising from their use. We can wear trainers and hang artwork to decorate a room; they are tangible physical objects, and the floor of their market value arises out of the physical commodities that comprise it, synthesized with craftsmanship or artistry—crypto is not a tangible commodity and thus has none of that, it’s nothing more than an entry in a database created out of thin air. However, there are historical cases of “pseudo-commodities” that, like crypto, have no intrinsic value and which are sold as collectibles, and where market liquidity arises out of more complicated social phenomena. In the Middle Ages, people collected indulgences from the Medieval church because they believed or were socialized into believing that possessing these church-issued certificates would act as a proxy for divine penance, a way of financializing forgiveness of sins to individuals who could not receive it through the sacrament of penance. The sale of indulgences, which—like crypto—were purely narrative-driven collectibles, was a way for the church to raise funds for various causes, such as the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The cost of an indulgence depended on one’s social status, with higher prices for the wealthy and lower costs for the poor. The church went so far as to create a thriving market of sophisticated contracts for both partial and plenary options granting various spiritual rights, all synthesized out of thin air.

Indulgences were the first purely-narrative-driven collectible bubble in human history and utilized the same social dynamics of crypto and predated Satoshi by 500 years. Whether you think indulgences were a scam is a philosophically interesting question. If one is a believer and buys into the idea of the infallibility of the Medieval church’s narrative, then for the finite price of three gold florins, you were buying eternal heavenly salvation—which is a pretty good trade. If one is a non-believer, indulgences were a racket—a scam in the truest sense. Sell the illiterate hoi polloi on an imagined fear built around a complex narrative and then profit from that fear in a self-sustaining closed loop that generates its own demand. And really, there is no “moderate” position here; the answer is black and white and entirely depends on the presupposition of faith in the narrative, which is incommensurate with the opposite position. Nevertheless, the case of asserting that both indulgences and crypto are a scam is absolutely a justified true belief if you reject the underlying presupposition they rest on. Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen, but a market for lemon-flavored fairy dust can never be anything but a scam.

Gambling

The second defensible position for crypto is that it is a gambling contract—most succinctly described by Charlie Munger’s Wall Street Journal op-ed as “a gambling contract with a nearly 100% edge for the house”, which is entirely accurate. A crypto token is a pathological edge case of a financial “asset” (although it stretches the term to absurd limits) with no income from economic activity and no claim on any underlying assets. The most eloquent description of this activity is from Martin Walker:

“Big Crypto firms have been buying and selling”nothing" for so long, mostly in return for different lumps of “nothing,” that many have genuinely come to believe that taking Nothing, giving it a name — and sometimes a story — combined with a little bit of trading back and forth with friends, gives “nothing” enormous value. Whether huge valuations for “nothing” tokens came from simply pumping up the market price of old school cryptocurrencies or creating complex DeFi (Decentralised Finance) structures, the belief in the value of Nothing makes is easy to lose sight of the fact of the underlying reality: it is the inflow of real money rather than “the technology,” “the community,” “the network” or “freedom” that gives crypto assets value."

John Maynard Keynes, the British economist and philosopher, famously stated that “the economic problem” is the struggle to reconcile the conflicting desires for economic goods, given the scarcity of resourcaes. In 1936, Keynes argued that the root of the economic problem lies in the limited resources available to meet the unlimited wants and needs of individuals. Keynesian economics asserts that the solution to the economic problem involves the active manipulation of aggregate demand through monetary and fiscal policies, which help to stimulate economic activity and increase the production and distribution of goods. Finance is thus a means to direct society’s resources towards efficient uses in the presence of imperfect information and unpredictable market conditions.

However, crypto represents a divergence entirely from a Keynesian worldview in that it has created this bizarre simulacrum of markets with all the trappings and veneer of finance but which has no pretense of being tethered to the economic problem at all. No goods, services or resources are being exchanged. Crypto is a Keynesian beauty contest for zero-sum get-rich-quick schemes. I call it the nothingness game, a bizarre contest in which participants continuously punt on get-rich-quick schemes for lumps of nothing based on their perception of which lump of nothing others believe is the most attractive. It’s a byzantine (and completely non-economic) casino game of creating elaborate stories and systems for trading lumps of nothing back and forth based on memes and sentiment. And it really is a remarkable spectacle to watch because it’s a pure exercise in an extraordinary collective hallucinatory delusion, the financial equivalent of watching a room full of LARPing wizards shooting imaginary fireballs at each other.

Now regulated gambling amongst consenting adults is not intrinsically problematic. It’s a form of consumption and entertainment, and while a Keynesian beauty contest for dog-themed lumps of nothing is genuinely bizarre, there’s no a priori rationale that it’s any more weird or arbitrary than poker or betting on a bunch of blokes kicking a football around a pitch. The problem is that, as Charlie Munger points out, it’s a gambling contract with a nearly 100% edge for the house, where neither the game, odds nor rules are fixed or presented accurately to consumers. Casino games are presented to the public honestly as casino games, the odds are printed on the table or machine, and there is an enormous body of regulation surrounding the activity. Nothing about the public presentation of crypto is honest because it is currently sold to both policymakers and the public as a financial investment, not the actual gambling contract it is. Until that changes, the entire crypto-gambling complex is an entirely non-economic unregulated casino built on material misrepresentation, or in other words, a scam.

No matter which crypto narrative one picks, following these ideas to their logical conclusions ends up in economic absurdities or the revelation that the narrative is based on misrepresentation and is thus a scam. Nevertheless, scams and absurd belief systems are universal fixtures of the human condition. The cynical opportunist stance is that it’s better to position oneself as running the gambling parlor or selling indulgences to prey on fellow man’s ignorance. Crypto is a morbid symptom of a society obsessed with wealth and so disheartened by the lack of opportunities for upward mobility that they spend their meager savings gambling on lumps of nothingness; however, their participation in the market only enriches the casino and inevitably deepens their conditions of despair. It’s incredibly bleak, and the biggest scam of crypto is not financial; it’s the anti-humanist philosophy at its core that turns victims into victimizers, rejects the premise of progress, and normalizes nihilism.

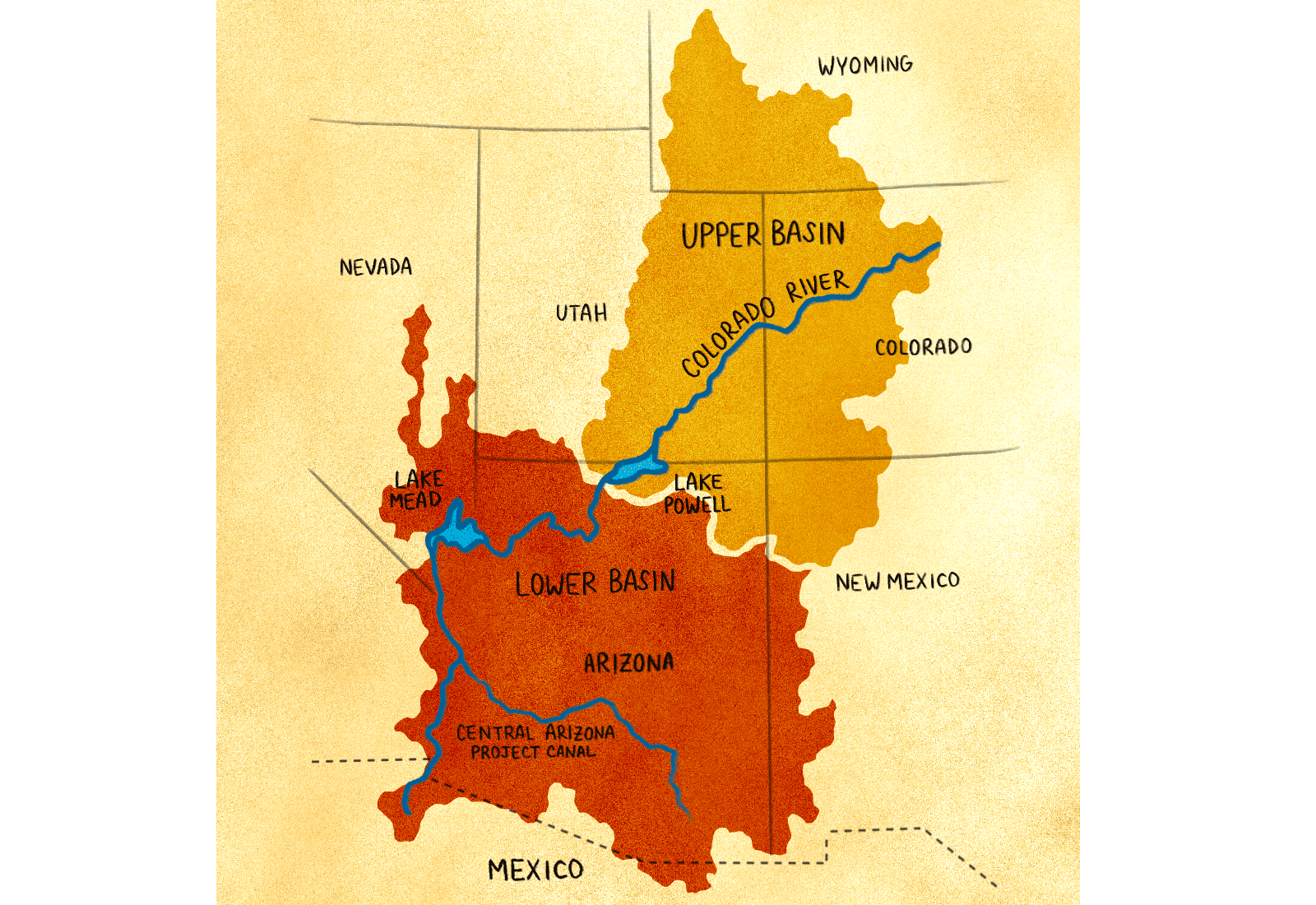

There’s a deal to save the Colorado River — if California doesn’t blow it up

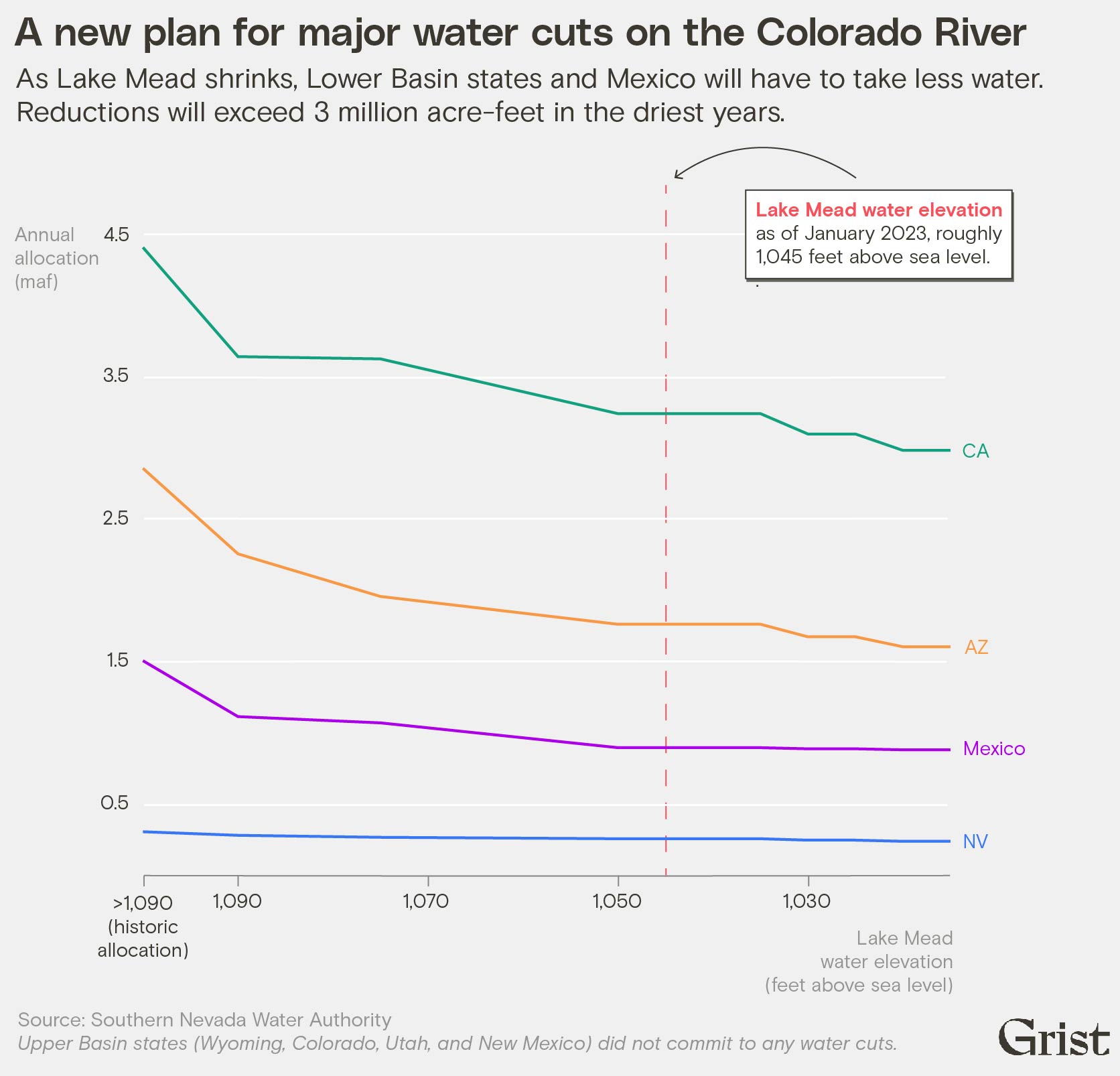

After months of tense negotiation, a half-dozen states have reached an agreement to drastically cut their water usage and stabilize the drought-stricken Colorado River — as long as California doesn’t blow up the deal. The plan, which was developed without the input of Mexico or Native American tribes that rely on the river, seeks to stave off total collapse in the river for another few years, giving water users time to find a comprehensive solution for the chronically-depleted waterway.

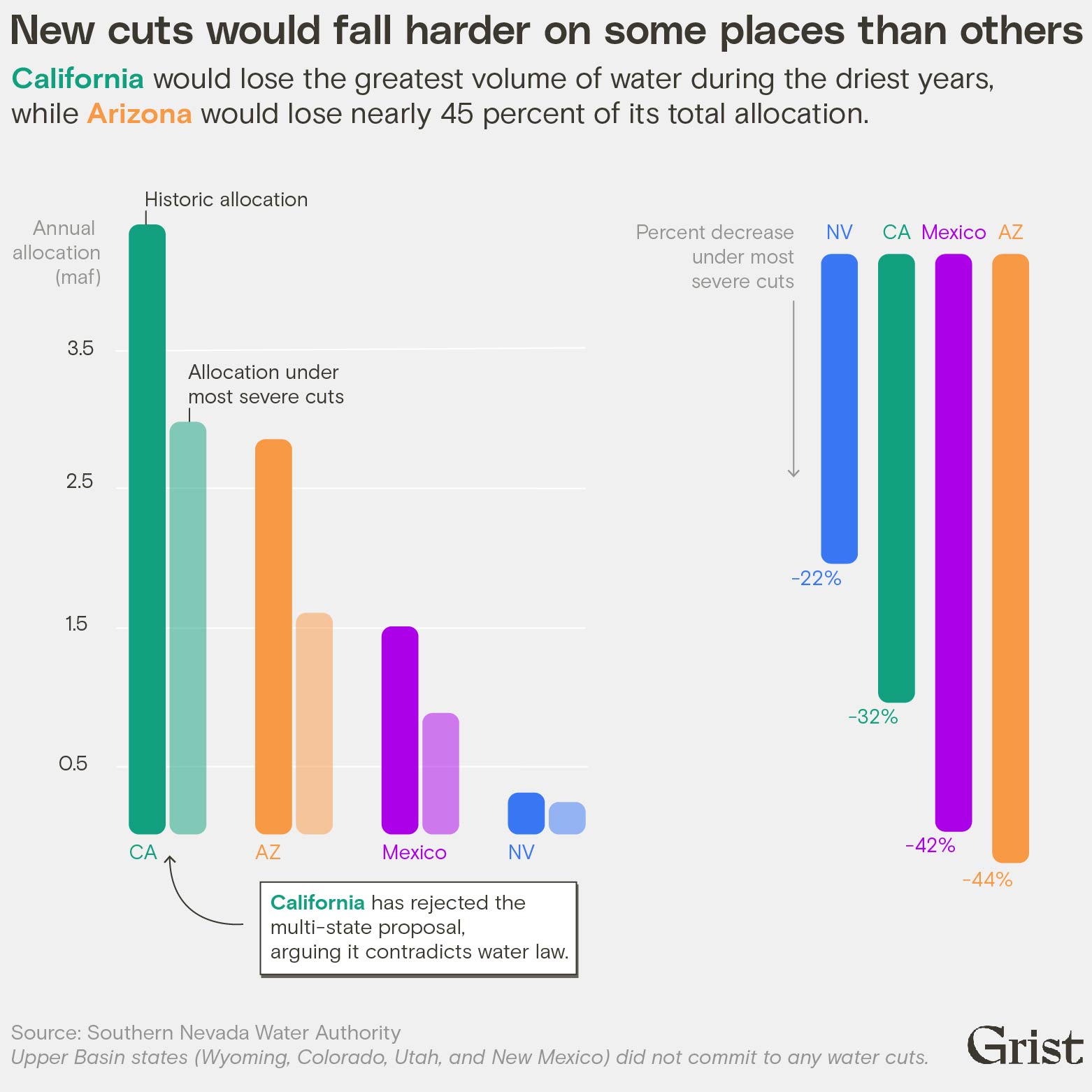

On Monday, six out of the seven states that rely on the Colorado announced their support for steep emergency cuts totaling more than 2 million acre-feet of water, or roughly a quarter of annual usage from the river. The multi-state agreement, prodded into existence by the Biden administration’s threats to impose its own cuts, will likely serve as a blueprint for the federal government as it manages the river over the next four years, ushering in a new era of conservation in the drought-wracked Southwest. While the exact consequences of these massive cuts are still largely uncertain, they will almost certainly spell disaster for water-intensive agriculture operations and new residential development in the region’s booming cities.

But California, which takes more water than any other state, has rejected the proposal as too onerous, instead proposing its own plan with a less stringent scheme for cutting water usage. If the federal government does adopt the six-state framework, powerful farmers in California’s Imperial Valley may sue to stop it, setting up a legal showdown that could derail the Biden administration’s drought response efforts.

Nevertheless, the general consensus on pursuing immediate, dramatic water cuts is unprecedented.

“It puts something down on the table that we haven’t had before,” said Elizabeth Koebele, an associate professor at the University of Nevada-Reno who studies the Colorado River. “The states are saying, ‘We recognize just how bad it is, and we’re willing to take cuts much, much sooner than we had previously agreed to.’”

The Colorado River has been oversubscribed for more than a century thanks to a much-maligned 1922 contract that allocated more water than actually existed, but it has also been shrinking over the past 20 years thanks to a millennium-scale drought made worse by climate change. Last year, as high winter temperatures caused the snowpack that feeds the river to vanish, water levels plummeted in the river’s two key reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, threatening to knock out electricity generation at two major dams.

Federal officials intervened in June, ordering the seven Colorado River Basin states to find a way to reduce their annual water usage by between 2 and 4 million acre-feet. This was a jaw-dropping demand, far more than the states had ever contemplated cutting, and they blew through an initial August deadline to find a solution. The feds upped the pressure in October, threatening to impose unilateral cuts if state officials didn’t work out a solution.

As the interstate talks proceeded, long-buried conflicts began to resurface. The first major conflict is between the Upper Basin states — Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah — and the Lower Basin states: Nevada, Arizona, California, and Mexico. The Upper Basin states argue that the Lower Basin states should be the ones to cut water in response to the drought. These states use much more water, the argument goes, and they also waste a lot of water that evaporates as it flows downstream through reservoirs and canals. The Lower Basin states, meanwhile, argue that no states should be exempt from cuts, given the scale of reductions needed.

The other main conflict is between Arizona and California, the two largest Lower Basin water users and the main targets of future cuts. California’s water rights trump Arizona’s, and therefore the Golden State argues that Arizona should shoulder almost the whole burden of future cuts. Arizona argues in turn that its farms and subdivisions have already cut their water usage in recent years as the drought has gotten worse, and that water-rich farmers in California should do more to help.

In the middle of these warring parties is Nevada, which takes only a tiny share of the river’s water and has emerged as the Switzerland of the Colorado River system over the past year. Water officials from the Silver State have been trying since late summer to broker a compromise between the Upper and Lower Basins and between Arizona and California, culminating in an intense session of talks in Las Vegas in December.

The talks were only partly successful. Officials managed to work out a framework that meets the Biden administration’s demands for major cuts, bringing an end to a year of uncertain back-and-forth. The proposal would cut more than a million acre-feet of water each from Arizona and California during the driest years, plus another 625,000 acre-feet from Mexico and 67,000 acre-feet from Nevada, adding new reductions to account for water that evaporates as it moves downstream. In return for these Lower Basin cuts, the Upper Basin states have agreed to move more water downstream to Lake Powell, helping protect that reservoir’s critical energy infrastructure — but they haven’t committed to reduce any water usage themselves.

“It seems like the Lower Basin states conceded to the Upper Basin,” said Koebele. An earlier version of the six-state proposal called for the Upper Basin to reduce water usage by a collective 500,000 acre-feet, but that call was absent from the final framework.

While the fight between the Upper and Lower Basin states appears neutralized, the conflict between the Lower Basin’s two biggest users is ongoing. Around 40 percent of the agreement’s proposed reductions come from California, where state officials have slammed it as a violation of their senior water rights, derived from a series of laws and court decisions known collectively as the “law of the river.”

“The modeling proposal submitted by the six other basin states is inconsistent with the Law of the River and does not form a seven-state consensus approach,” said J.B. Hamby, California’s lead representative in the talks. Hamby argued that penalizing California for evaporation losses on the river contradicts the legal precedent that gives California clear seniority over Arizona.

Officials from the Golden State released their own rough framework for dealing with the drought on Tuesday. The plan offers a more forgiving schedule than the six-state framework, saving the largest cuts for when Lake Mead’s water level is extremely low, and it forces more pain on Arizona and Mexico. The framework only requires California to cut around 400,000 acre-feet of new water, which the biggest water users already volunteered to do last September in exchange for federal money to restore the drought-stricken Salton Sea. Water users in the state haven’t made new commitments since.

If the Biden administration moves forward with the plan, it may trigger legal action from the Imperial Irrigation District, which represents powerful fruit and vegetable farmers in California’s Imperial Valley. The district sued to block a previous drought agreement back in 2019, and its farmers have the most to lose from the new framework, since they’ve been insulated from all previous cuts. The state’s other major water user, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, has signaled tentative approval for the broad strokes of six-state formula, indicating that a compromise between the two plans might be possible, although it’s not clear such a compromise would please Imperial’s farmers.

“I don’t see how we avoid Imperial suing, other than a bunch of big snowpack,” said John Fleck, a professor of water policy at the University of New Mexico. In response to a request for comment from Grist about litigation, an Imperial spokesperson emphasized the need for “constructive dialogue and mutual understanding.” If Imperial did sue and win, the outcome would likely be even further pain for Arizona and Mexico, where farmers and cities are already struggling to deal with previous cuts.

Koebele told Grist that while the exact numbers may change, federal officials will likely adopt some version of the six-state proposal by the end of the summer. Even a modified version would alter life in the Southwest over the next four years, imposing a harsh new regime on a region whose water-guzzling produces a substantial portion of the nation’s vegetables and cattle feed. Major cities like Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Tijuana would also see water cuts, threatening growth in those places.

Steep as the new cuts are, though, they will only last until 2026, when basin leaders will gather again to work out a long-term plan for managing the river over the next two decades. Unlike the current round of emergency talks, that long-term negotiation will include representatives from Mexico and the dozens of Native American tribes that rely on the river.

Koebele said that the questions in those talks will be even more difficult than the ones the states are debating now. Instead of just figuring out who takes cuts in the driest years, the parties will have to figure out how to apportion a perennially smaller river while also fulfilling new tribal claims on long-sought water rights. The present crisis has only delayed progress on those bigger questions.

“Because of the dire situation, we’ve really had to turn our attention to managing for the present,” she said. “So these actions feel more like a Band-Aid to me.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline There’s a deal to save the Colorado River — if California doesn’t blow it up on Feb 1, 2023.

Even with legal protections, extreme heat and wildfire take a toll on farmworkers

Mass shootings at two California mushroom farms last month drew national attention to the dismal working and living conditions imposed on California farmworkers. Surveys of California Terra Garden and Concord Farms, where the assailant had worked, revealed families living in trailers and shipping containers, using makeshift kitchens and portable toilets. State and federal officials have opened investigations into the farms, where workers reported earning below minimum wage.

The conditions are “very typical images … for California and for the country,” Irene de Barraicua, director of operations at Lideres Campesinas, a network of female farmworker leaders, told the Washington Post after the shooting.

Now, the first comprehensive assessment of California farmworker health since 1999, released Friday, demonstrates just how typical those conditions are – and how climate change, and widening inequality, are exacerbating challenges for these workers, some of the most disenfranchised residents of the state.

The landmark study, by the University of California, Merced’s Community and Labor Center, in partnership with organizations that serve farmworkers across the state, and funded by the California Department of Public Health, surveyed over 1,200 workers about their health, well-being, and workplace conditions. It found widespread exposure to wildfire smoke and pesticides, rodents and cockroaches in rental units, inadequate safety training, and lack of access to clean drinking water. Half of all farmworkers surveyed reported going without health insurance, even when between one-third and one-half had at least one chronic health condition.

“Even through these major climate disasters the food supply has not been interrupted,” said Edward Flores, a professor of sociology at UC Merced and one of the report’s authors. “But the conditions that people work in have become riskier to their well-being. And they have fewer resources with which to weather a major event.”

Temperatures can already exceed 110 degrees Fahrenheit in areas including the San Joaquin Valley, Imperial Valley, Coachella Valley, and Sacramento Valley, where much of the state’s farming happens, and the heat is only getting worse. Meanwhile, intense precipitation events cause damage to substandard rental units, and extreme fire weather days, which have doubled since the 1980s, increase the risk of respiratory illness.

More than one in three survey respondents, 92 percent of whom were renters, experienced problems keeping a house cool or warm. And about 15 percent encountered rotting wood, water damage, and leaks.

California’s Division of Occupational Health and Safety, or Cal/OSHA, has various standards in place to protect workers from extreme weather and other occupational hazards. For outdoor workers, for example, employers have to provide fresh water, access to shade, and cool-down rest breaks at 80 degrees Fahrenheit. They also have to train employees and supervisors on the signs of heat illness and maintain a heat illness prevention plan, with written procedures for what to do in case of an emergency.

These standards are some of the strongest in the nation. Still, they often don’t protect farmworkers, who report widespread violations and non-compliance. Almost half the farmworkers surveyed had never been provided with a heat illness prevention plan. And 15 percent received no heat illness training at all.

During wildfire season, 13 percent had to work when smoke made it difficult to breathe, often without respiratory protective equipment as required by Cal/OSHA. While state law also requires pesticide safety training to be provided in a language that farmworkers understand, about half who had worked with the chemicals in the past year did so without receiving adequate training.

Even more concerning, when workplaces were out of compliance with labor laws, 36 percent of farmworkers said they would not be willing to file a complaint. Most of the time, that was for fear of employer retaliation. The fact that only 41 percent of the respondents had access to unemployment insurance suggests that 59 percent weren’t documented, said Edward Flores. “A very vulnerable person has to take the job that’s available to them, even if it’s not up to code.”

As climate change intensifies, challenges facing farmworkers, and especially undocumented workers, will only increase, the report warns. “Whether it’s record heat, catastrophic wildfires, or major floods, farmworkers either have to work in dangerous conditions or they’re unable to work,” said Flores. “They don’t have the same access to a safety net.”

The researchers hope that as California invests in reducing its emissions and helping agriculture adapt to a warming world, the data from the report will lead to more integrated climate, economic, and labor policy. “We should be thinking about a cohesive strategy so that, for example, investment in technology to improve the way that crops are produced might also be done with farmer organizations at the table, with input from health and safety advocates,” said Flores.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Even with legal protections, extreme heat and wildfire take a toll on farmworkers on Feb 7, 2023.

Hal Crook about the Kazoo - Microtonal Groovizator

http://www.patreon.com/publio

Follow me on Instagram↓

http://www.instagram.com/publiodb

Hal Crook is all about playing microtonal melodies with the kazoo.

Hi Hal.

I'm using a 24 note octave for Microtonal Groovizator videos.

≠ = Half sharp

d = Half flat

Original clip here↓

https://youtu.be/Rx17-Axqtt4

Emmanuel don't do it! - Microtonal Harmonizator (24-TET)

http://www.patreon.com/publio

Follow me on Instagram↓

http://www.instagram.com/publiodb

Without Emmanuel this melodies wouldn't exist.

You can follow Emmanuel here↓

http://www.instagram.com/knucklebumpfarms

I'm using a 24 note octave for Microtonal Harmonizator videos.

≠ = Half sharp

d = Half flat

Memories Emerge in Stephen Wong Chun Hei’s Paintings as Vivid Saturated Landscapes

“MacLehose Trail Section 4” (2022), acrylic on canvas, 150 x 200 centimeters. Photos by Bonhams HK, all images © Stephen Wong Chun Hei

Vivid palettes of blues, greens, and pink saturate Stephen Wong Chun Hei’s landscapes, which translate memories of travel into dream-like paintings in acrylic. The artist considers each work a vessel for the impressions of places he’s traveled or hiked. “I never try to capture just one moment in a landscape. The colours are ever-changing through time,” Hei tells Colossal. “This is the reason that the colours in my paintings are not realistic or naturalistic in appearance. I would like them to be more subjective.”

Many of the paintings originate in a sketchbook, which the artist brings along on his adventures and back to his Hong Kong-based studio. “When I work on canvas, I also got the feeling of travel with every brushstroke and colour used,” he shares.

Hei is currently preparing for a show in May at Tang Contemporary, and one of his works will also be on view with Gallery Exit for Art Basel Hong Kong. He’s currently traveling to multiple countries to explore their landscapes, which he hasn’t been able to do since before the COVID-19 pandemic. Follow those excursions on his site and Instagram. (via This Isn’t Happiness)

“MacLehose Trail Section 2” (2022), acrylic on canvas, 150 x 200 centimeters

“MacLehose Trail Section 5” (2022), acrylic on canvas, 150 x 150 centimeters

“MacLehose Trail Section 6” (2022), acrylic on canvas, 150 x 120 centimeters

“MacLehose Trail Uphill at Section 5” (2022), acrylic on canvas, 40 x 30 centimeters

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. The article Memories Emerge in Stephen Wong Chun Hei’s Paintings as Vivid Saturated Landscapes appeared first on Colossal.

A Kinetic Glass Greenhouse Blossoms into a Massive Open-Air Terrarium

All images by Hufton + Crow, courtesy of Heatherwick Studio, shared with permission

A kinetic design by Heatherwick Studio transforms a sleek glass enclosure on the Woolbeding Gardens property into an elegant flower in full bloom. Situated at the edge of the West Sussex estate, “Glasshouse” protects a melange of sub-tropical flora from southwest China, particularly those found along the Silk Road. A hydraulic mechanism opens the 10 panels of the aluminum-and-steel structure during warmer temperatures, allowing for ventilation within the 141-square-meter terrarium and transforming the architectural form into a blossoming botanical.

Heatherwick Studio is responsible for an eclectic array of designs, including a silo-turned-art-gallery and a honeycomb vessel for pedestrians, and you can follow the latest on Instagram.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. The article A Kinetic Glass Greenhouse Blossoms into a Massive Open-Air Terrarium appeared first on Colossal.

Nighttime Reveals the Inner Vitality of Reskate’s Dynamic Glow-in-the-Dark Murals

Nighttime view of “Eulalia” (2022-23), Mérida, Extremadura, Spain. All images © Reskate Studio, shared with permission

By day, Reskate Studio’s bold, deceptively simple murals outline the forms of rope, a mountain, or a dog in a neutral palette. When the sun sets, though, an entirely new image emerges from within the unassuming motif. María López and Javier de Riba, who work collaboratively as Reskate, continue to paint bold, light-sensitive works as part of their ongoing Harreman Project (previously). The artists say their intention is “to try to light up dark corners of cities, both installing new lights and encouraging citizens to interact with the wall—painting with light on it.”