Originally published in the November 1984 issue

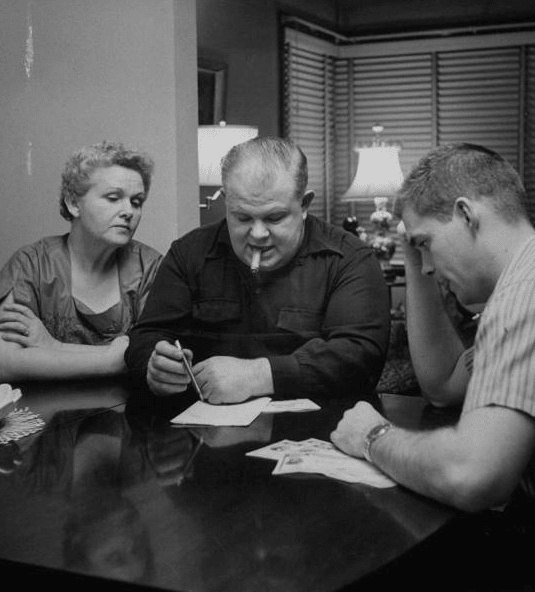

I last saw Hiers in a rice paddy in Vietnam. He was nineteen then--my wonderfully skilled and maddeningly insubordinate radio operator. For months we were seldom more than three feet apart. Then one day he went home, and fifteen years passed before we met by accident last winter at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington. A few months later I visited Hiers and his wife. Susan, in Vermont, where they run a bed-and -breakfast place. The first morning we were up at dawn trying to save five newborn rabbits. Hiers built a nest of rabbit fur and straw in his barn and positioned a lamp to provide warmth against the bitter cold.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

"What people can't understand," Hiers said, gently picking up each tiny rabbit and placing it in the nest, "is how much fun Vietnam was. I loved it. I loved it, and I can't tell anybody."

Hiers loved war. And as I drove back from Vermont in a blizzard, my children asleep in the back of the car, I had to admit that for all these years I also had loved it, and more than I knew. I hated war, too. Ask me, ask any man who has been to war about his experience, and chances are we'll say we don't want to talk about it--implying that we hated it so much, it was so terrible, that we would rather leave it buried. And it is no mystery why men hate war. War is ugly, horrible, evil, and it is reasonable for men to hate all that. But I believe that most men who have been to war would have to admit, if they are honest, that somewhere inside themselves they loved it too, loved it as much as anything that has happened to them before or since. And how do you explain that to your wife, your children, your parents, or your friends?

That's why men in their sixties and seventies sit in their dens and recreation rooms around America and know that nothing in their life will equal the day they parachuted into St. Lo or charged the bunker on Okinawa. That's why veterans' reunions are invariably filled with boozy awkwardness, forced camaraderie ending in sadness and tears: you are together again, these are the men who were your brothers, but it's not the same, can never be the same. That's why when we returned from Vietnam we moped around, listless, not interested in anything or anyone. Something had gone out of our lives forever, and our behavior on returning was inexplicable except as the behavior of men who had lost a great perhaps the great-love of their lives, and had no way to tell anyone about it.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

In part we couldn't describe our feelings because the language failed us: the civilian-issue adjectives and nouns, verbs and adverbs, seemed made for a different universe. There were no metaphors that connected the war to everyday life. But we were also mute, I suspect, out of shame. Nothing in the way we are raised admits the possibility of loving war. It is at best a necessary evil, a patriotic duty to be discharged and then put behind us. To love war is to mock the very values we supposedly fight for. It is to be insensitive, reactionary, a brute.

But it may be more dangerous, both for men and nations, to suppress the reasons men love war than to admit them. In Apocalypse Now, Robert Duvall, playing a brigade commander, surveys a particularly horrific combat scene and says, with great sadness, "You know, someday this war's gonna be over. " He is clearly meant to be a psychopath, decorating enemy bodies with playing cards, riding to war with Wagner blaring. We laugh at him--Hey! nobody's like that! And last year in Grenada American boys charged into battle playing Wagner, a new generation aping the movies of Vietnam the way we aped the movies of World War 11, learning nothing, remembering nothing.

Alfred Kazin wrote that war is the enduring condition of twentieth-century man. He was only partly right. War is the enduring condition of man, period. Men have gone to war over everything from Helen of Troy to Jenkins's ear. Two million Frenchmen and Englishmen died in muddy trenches in World War I because a student shot an archduke. The truth is, the reasons don't matter. There is a reason for every war and a war for every reason.

For centuries men have hoped that with history would come progress, and with progress, peace. But progress has simply given man the means to make war even more horrible; no wars in our savage past can begin to match the brutality of the wars spawned in this century, in the beautifully ordered, civilized landscape of Europe, where everyone is literate and classical music plays in every village cafe. War is not all aberration; it is part of the family. the crazy uncle we try--in vain--to keep locked in the basement.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Consider my own example. I am not a violent person. I have not been in a fight since grade school. Aside from being a fairly happy-go-lucky carnivore, I have no lust for blood, nor do I enjoy killing animals, fish, or even insects. My days are passed in reasonable contentment, filled with the details of work and everyday life. I am also a father now, and a male who has helped create life is war's natural enemy. I have seen what war does to children, makes them killers or victims, robs them of their parents, their homes, and their innocence--steals their childhood and leaves them marked in body, mind, and spirit.

I spent most of my combat tour in Vietnam trudging through its jungles and rice paddies without incident, but I have seen enough of war to know that I never want to fight again, and that I would do everything in my power to keep my son from fighting. Then why, at the oddest times--when I am in a meeting or running errands, or on beautiful summer evenings, with the light fading and children playing around me--do my thoughts turn back fifteen years to a war I didn't believe in and never wanted to fight? Why do I miss it?

I miss it because I loved it, loved it in strange and troubling ways. When I talk about loving war I don't mean the romantic notion of war that once mesmerized generations raised on Walter Scott. What little was left of that was ground into the mud at Verdun and Passchendaele: honor and glory do not survive the machine gun. And it's not the mindless bliss of martyrdom that sends Iranian teenagers armed with sticks against Iraqi tanks. Nor do I mean the sort of hysteria that can grip a whole country, the way during the Falklands war the English press inflamed the lust that lurks beneath the cool exterior of Britain. That is vicarious war, the thrill of participation without risk, the lust of the audience for blood. It is easily fanned, that lust; even the invasion of a tiny island like Grenada can do it. Like all lust, for as long as it lasts it dominates everything else; a nation's other problems are seared away, a phenomenon exploited by kings, dictators, and presidents since civilization began.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

And I don't mean war as an addiction, the constant rush that war junkies get, the crazies mailing ears home to their girlfriends, the zoomies who couldn't get an erection unless they were cutting in the afterburners on their F-4s. And, finally, I'm not talking about how some men my age feel today, men who didn't go to war but now have a sort of nostalgic longing for something they missed, some classic male experience, the way some women who didn't have children worry they missed something basic about being a woman, something they didn't value when they could have done it.

I'm talking about why thoughtful, loving men can love war even while knowing and hating it. Like any love, the love of war is built on a complex of often contradictory reasons. Some of them are fairly painless to discuss; others go almost too deep, stir the caldron too much. I'll give the more respectable reasons first.

Part of the love of war stems from its being an experience of great intensity; its lure is the fundamental human passion to witness, to see things, what the Bible calls the lust of the eye and the Marines in Vietnam called eye fucking. War stops time, intensifies experience to the point of a terrible ecstasy. It is the dark opposite of that moment of passion caught in "Ode on a Grecian Urn": "For ever warm and still to be enjoy'd/ For ever panting, and forever young. " War offers endless exotic experiences, enough "I couldn't fucking believe it! "'s to last a lifetime.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Most people fear freedom; war removes that fear. And like a stem father, it provides with its order and discipline both security and an irresistible urge to rebel against it, a constant yearning to fly over the cuckoo's nest. The midnight requisition is an honored example. I remember one elaborately planned and meticulously executed raid on our principal enemy--the U.S. Army, not the North Vietnamese--to get lightweight blankets and cleaning fluid for our rifles repeated later in my tour, as a mark of my changed status, to obtain a refrigerator and an air conditioner for our office. To escape the Vietnamese police we tied sheets together and let ourselves down from the top floor of whorehouses, and on one memorable occasion a friend who is now a respectable member of our diplomatic corps hid himself inside a rolled-up Oriental rug while the rest of us careered off in the truck. leaving him to make his way back stark naked to our base six miles away. War, since it steals our youth, offers a sanction to play boys' games.

War replaces the difficult gray areas daily life with an eerie, serene clarity. In war you usually know who is your enemy and who is your friend, and are given means of dealing with both. (That was, incidentally, one of the great problems with Vietnam: it was hard to tell friend from foe--it was too much like ordinary Life.)

War is an escape from the everyday into a special world where the bonds that hold us to our duties in daily life--the bonds of family, community, work, disappear. In war, all bets are off. It's the frontier beyond the last settlement, it's Las Vegas. The men who do well in peace do not necessarily do well at war, while those who were misfits and failures may find themselves touched with fire. U. S. Grant, selling firewood on the streets of St. Louis and then four years later commanding the Union armies, is the best example, although I knew many Marines who were great warriors but whose ability to adapt to civilian life was minimal.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

I remember Kirby, a skinny kid with JUST YOU AND ME LORD tattooed on his shoulder. Kirby had extended his tour in Vietnam twice. He had long since ended his attachment to any known organization and lived alone out in the most dangerous areas, where he wandered about night and day, dressed only in his battered fatigue trousers with a .45 automatic tucked into the waistband, his skinny shoulders and arms as dark as a Montagnard's.

One day while out on patrol we found him on the floor of a hut, being tended by a girl in black pajamas, a bullet wound in his arm.

He asked me for a cigarette, then eyed me, deciding if I was worth telling his story to. "I stopped in for a mango, broad daylight, and there bigger'n hell were three NVA officers, real pretty tan uniforms. They got this map spread out oil a table, just eyeballin' it, makin' themselves right at home. They looked at me. I looked at them. Then they went for their nine millimeters and I went for my .45. "

"Yeah?"I answered. "So what happened

"I wasted 'em," he said, then puffed on his cigarette. Just another day at work, killing three men on the way to eat a mango.

How are you ever going to go back to the world?" I asked him. (He didn't. A few months later a ten-year-old Vietcong girl blew him up with a command-detonated booby trap.

War is a brutal, deadly game, but a game, the best there is. And men love games. You can come back from war broken in mind or body, or not come back at all. But if you come back whole you bring with you the knowledge that you have explored regions of your soul that in most men will always remain uncharted. Nothing I had ever studied was as complex or as creative as the small-unit tactics of Vietnam. No sport I had ever played brought me to such deep awareness of my physical and emotional limits.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

One night not long after I had arrived in Vietnam, one of my platoon's observation on posts heard enemy movement. I immediately lost all saliva in my mouth. I could not talk; not a sound would pass my lips. My brain erased as if the plug had been pulled--I felt only a dull hum throughout my body, a low-grade current coursing through me like electricity through a power line. After a minute I could at least grunt, which I did as Hiers gave orders to the squad leaders, called in artillery and air support, and threw back the probe. I was terrified. I was ashamed, and I couldn't wait for it to happen again.

The enduring emotion of war, when everything else has faded, is comradeship. A comrade in war is a man you can trust with anything, because you trust him with your life. "It is," Philip Caputo wrote in A Rumor of War "unlike marriage, a bond I that cannot be broken by a word, by boredom or divorce, or by anything other than death." Despite its extreme right-wing image, war is the only utopian experience most of us ever have. Individual possessions and advantage count for nothing: the group is everything What you have is shared with your friends. It isn't a particularly selective process, but a love that needs no reasons, that transcends race and personality and education--all those things that would make a difference in peace. It is, simply, brotherly love.

What made this love so intense was that it had no limits, not even death. John Wheeler in Touched with Fire quotes the Congressional Medal of Honor citation of Hector Santiago-Colon: "Due to the heavy volume of enemy fire and exploding grenades around them, a North Vietnamese soldier was able to crawl, undetected, to their position. Suddenly, the enemy soldier lobbed a hand grenade into Sp4c. Santiago-Colon's foxhole. Realizing that there was no time to throw the grenade out of his position, Sp4c., Santiago-Colon retrieved the grenade, tucked it into his stomach, and turning away from his comrades, and absorbed the full impact of the blast. " This is classic heroism, the final evidence of how much comrades can depend on each other. What went through Santiago- Colon's mini for that split second when he could just a easily have dived to safety? It had to be this: my comrades are more important than my most valuable possession--my own life.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Isolation is the greatest fear in war. The military historian S.L.A. Marshall con ducted intensive studies of combat incidents during World War 11 and Korea and discovered that, at most, only 25 percent of the men who were under fire actually fired their own weapons. The rest cowered behind cover, terrified and helpless--all systems off. Invariably, those men had felt alone, and to feel alone in combat is to cease to function; it is the terrifying prelude to the final loneliness of death. The only men who kept their heads felt connected to other men, a part of something as if comradeship were some sort of collective life-force, the power to face death and stay conscious. But when those men cam home from war, that fear of isolation stayed with many of them, a tiny mustard seed fallen on fertile soil.

When I came back from Vietnam I tried to keep up with my buddies. We wrote letters, made plans to meet, but something always came up and we never seemed to get together. For a few year we exchanged Christmas cards, then nothing . The special world that had sustain our intense comradeship was gone. Everyday life--our work, family, friends--reclaimed us, and we grew up.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

But there was something not right about that. In Vietnam I had been closer to Hiers, for example, than to anyone before or since. We were connected by the radio, our lives depended on it, and on eachother. We ate, slept, laughed, and we terrified together. When I first arrived in Vietnam I tried to get Hiers to salute me, but he simply wouldn't do it, mustering at most a "Howdy, Lieutenant, how's it hanging" as we passed. For every time that I didn't salute I told him he would have to fill a hundred sandbags.

We'd reached several thousand sandbags when Hiers took me aside and said "Look, Lieutenant, I'll be happy to salute you, really. But if I get in the habit back here in the rear I may salute you when we're out in the bush. And those gooks a just waiting for us to salute, tell 'em who the lieutenant is. You'd be the first one blown away." We forgot the sandbags and the salutes. Months later, when Hiers left the platoon to go home, he turned to me as I stood on our hilltop position, and gave me the smartest salute I'd ever seen. I shot him the finger, and that was the last I saw of him for fifteen years. When we met by accident at the Vietnam memorial it was like a sign; enough time had passed-we were old enough to say goodbye to who we had been and become friends as who we had become.

For us and for thousands of veterans the memorial was special ground. War is theater, and Vietnam had been fought without a third act. It was a set that hadn't been struck; its characters were lost there, with no way to get off and no more lines to say. And so when we came to the Vietnam memorial in Washington we wrote our own endings as we stared at the names on the wall, reached out and touched them, washed them with our tears, said goodbye. We are older now, some of us grandfathers, some quite successful, but the memorial touched some part of us that is still out there, under fire, alone. When we came to that wait and met the memories of our buddies and gave them their due, pulled them tip from their buried places and laid our love to rest, we were home at last.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

For all these reasons, men love war. But these are the easy reasons, the first circle the ones we can talk about without risk of disapproval, without plunging too far into the truth or ourselves. But there are other, more troubling reasons why men love war. The love of war stems from the union, deep in the core of our being between sex and destruction, beauty and horror, love and death. War may be the only way in which most men touch the mythic domains in our soul. It is, for men, at some terrible level, the closest thing to what childbirth is for women: the initiation into the power of life and death. It is like lifting off the corner of the universe and looking at what's underneath. To see war is to see into the dark heart of things, that no-man's-land between life and death, or even beyond.

And that explains a central fact about the stories men tell about war. Every good war story is, in at least some of its crucial elements, false. The better the war story, the less of it is likely to be true. Robert Graves wrote that his main legacy from World War I was "a difficulty in telling tile truth. " I have never once heard a grunt tell a reporter a war story that wasn't a lie, just as some of the stories that I tell about the war are lies. Not that even the lies aren't true, on a certain level. They have a moral, even a mythic, truth, rather than a literal one. They reach out and remind the tellers and listeners of their place in the world. They are the primitive stories told around the fire in smoky teepees after the pipe has been passed. They are all, at bottom, the same.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Some of the best war stories out Of Vietnam are in Michael Heir's Dispatches One of Heir's most quoted stories goes like this: "But what a story he told me, as one pointed and resonant as any war story I ever heard. It took me a year to understand it: "'Patrol went up the mountain. One man came back. He died before he could tell its What happened.'

" I waited for the rest, but it seemed not to be that kind of story; when I asked him what had happened he just looked like he felt sorry for me, fucked if he'd waste time telling stories to anyone as dumb as I was."

It is a great story, a combat haiku, all negative space and darkness humming with portent. It seems rich, unique to Vietnam. But listen, now, to this:

"We all went up to Gettysburg, the summer of '63: and some of us came back from there: and that's all except the details. " That is the account of Gettysburg by one Praxiteles Swan, onetime captain of the Confederate States Army. The language is different, but it is the same story. And it is a story that I would imagine has been told for as long as men have gone to war. Its purpose is not to enlighten but to exclude; its message is riot its content but putting the listener in his place. I suffered, I was there. You were not. Only those facts matter. Everything else is beyond words to tell. As was said after the worst tragedies in Vietnam: "Don't mean nothin'." Which meant, "It means everything it means too much." Language overload.

War stories inhabit the realm of myth because every war story is about death. And one of the most troubling reasons men love war is the love of destruction, the thrill of killing. In his superb book on World War II, The Warriors,J. Glenn Gray wrote that "thousands of youths who never suspect the presence of such an impulse in themselves have learned in military life the mad excitement of destroying." It's what Hemingway meant when he wrote, "Admit that you have liked to kill as all who are soldiers by choice have enjoyed it it some time whether they lie about it or not."

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

My platoon and I went through Vietnam burning hooches (note how language liberated US--we didn't burn houses and shoot people: we burned hooches and shot gooks), killing dogs and pigs and chickens, destroying, because, as my friend Hiers put it, "We thought it was fun at the time." As anyone who has fired a bazooka or an M-60 machine gun knows, there is something to that power in your finger, the soft, seductive touch of the trigger. It's like the magic sword, a grunt's Excalibur: all you do is move that finger so imperceptibly just a wish flashing across your mind like a shadow, not even a full brain synapse, and I poof in a blast of sound and energy and light a truck or a house or even people disappear, everything flying and settling back into dust.

There is a connection between this thrill and the games we played as children, the endless games of cowboys and Indians and war, the games that ended with "Bang bang you're dead," and everyone who was "dead" got up and began another game. That's war as fantasy, and it's the same emotion that touches us in war movies and books, where death is something without consequence, and not something that ends with terrible finality as blood from our fatally fragile bodies flows out onto the mud. Boys aren't the only ones prone to this fantasy; it possesses the old men who have never been to war and who preside over our burials with the same tears they shed when soldiers die in the movies--tears of fantasy, cheap tears. The love of destruction and killing in war stems from that fantasy of war as a game, but it is the more seductive for being indulged at terrible risk. It is the game survivors play, after they have seen death up close and learned in their hearts how common, how ordinary, and how inescapable it is.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

I don't know if I killed anyone in Vietnam but I tried as hard as I could. I fired at muzzle flashes in tile night, threw grenades during ambushes, ordered artillery and bombing where I thought tile enemy was. Whenever another platoon got a higher body count, I was disappointed: it was like suiting up for the football game and then not getting to play. After one ambush my men brought back the body of a North Vietnamese soldier. I later found the dead man propped against some C-ration boxes; he had on sunglasses, and a Playboy magazine lay open in his lap; a cigarette dangled jauntily from his mouth, and on his head was perched a large and perfectly formed piece of shit.

I pretended to be Outraged, since desecrating bodies was frowned on as un-American and counterproductive. But it wasn't outrage I felt. I kept my officer's face on, but inside I was... laughing. I laughed--I believe now--in part because of some subconscious appreciation of this obscene linkage of sex and excrement and 'death; and in part because of the exultant realization that he--whoever he had been--was dead and I--special, unique I me--was alive. He was my brother, but I knew him not. The line between life and death is gossamer thin; there is joy. true joy, in being alive when so many around you are not. And from the joy of being alive in death's presence to the joy of causing death is, unfortunately, not that great a step.

A lieutenant colonel I knew, a true intellectual, was put in charge of civil affairs, the work we did helping the Vietnamese grow rice and otherwise improve their lives. He was a sensitive man who kept a journal and seemed far better equipped for winning hearts and minds than for combat command. But he got one, and I remember flying out to visit his fire base the night after it had been attacked by an NVA sapper unit. Most of the combat troops I had been out on an operation, so this colonel mustered a motley crew of clerks and cooks and drove the sappers off, chasing them across tile rice paddies and killing dozens of these elite enemy troops by the light of flares. That morning, as they were surveying what they had done and loading the dead NVA--all naked and covered with grease and mud so they could penetrate the barbed wire--on mechanical mules like so much garbage, there was a look of beatific contentment on tile colonel's face that I had not seen except in charismatic churches. It was the look of a person transported into ecstasy.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

And I--what did I do, confronted with this beastly scene? I smiled back. 'as filled with bliss as he was. That was another of the times I stood on the edge of my humanity, looked into the pit, and loved what I saw there. I had surrendered to an aesthetic that was divorced from that crucial quality of empathy that lets us feel the sufferings of others. And I saw a terrible beauty there. War is not simply the spirit of ugliness, although it is certainly that, the devil's work. But to give the devil his due,it is also an affair of great and seductive beauty.

Art and war were for ages as linked as art and religion. Medieval and Renaissance artists gave us cathedrals, but they also gave us armor sculptures of war, swords and muskets and cannons of great beauty, art offered to the god of war as reverently as the carved altars were offered to the god of love. War was a public ritual of the highest order, as the beautifully decorated cannons in the Invalids in Paris and the chariots with their depict ions of the gods in the Metropolitan Museum of Art so eloquently attest Men love their weapons, not simply for helping to keep them alive, but for a deeper reason. They love their rifles and their knives for the same reason that the medieval warriors loved their armor and their swords: they are instruments of beauty.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

War is beautiful. There is something about a firefight at night, something about the mechanical elegance of an M -60 machine gun. They are everything they should be, perfect examples of their form. When you are firing out at night, the red racers go out into tile blackness is if you were drawing with a light pen. Then little dots of light start winking back, and green tracers from the AK-47s begin to weave ill with the red to form brilliant patterns that seem, given their great speeds, oddly timeless, as if they had been etched on the night. And then perhaps the gunships called Spooky come in and fire their incredible guns like huge hoses washing down from the sky, like something God would do when He was really ticked off. And then the flares pop, casting eerie shadows as they float down on their little parachutes, swinging in the breeze, and anyone who moves, in their light seems a ghost escaped from hell.

Daytime offers nothing so spectacular, but it also has its charms. Many men loved napalm, loved its silent power, the way it could make tree lines or houses explode as if by spontaneous combustion. But I always thought napalm was greatly overrated, unless you enjoy watching tires burn. I preferred white phosphorus, which exploded with a fulsome elegance, wreathing its target in intense and billowing white smoke, throwing out glowing red comets trailing brilliant white plumes I loved it more--not less --because of its function: to destroy, to kill. The seduction of War is in its offering such intense beauty--divorced from I all civilized values, but beauty still.

Most men who have been to war, and most women who have been around it, remember that never in their lives did they have so heightened a sexuality. War is, in short. a turn-on. War cloaks men in a coat that conceals the limits and inadequacies of their separate natures. It gives them all aura, a collective power, an almost animal force. They aren't just Billy or Johnny or Bobby, they are soldiers! But there's a price for all that: the agonizing loneliness of war, the way a soldier is cut off from everything that defines him as an individual--he is the true rootless man.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

The uniform did that, too, and all that heightened sexuality is not much solace late it night when the emptiness comes.

There were many men for whom this condition led to great decisions. I knew a Marine in Vietnam who was a great rarity, an Ivy League graduate. He also had an Ivy League wife, but lie managed to fall in love with a Vietnamese bar girl who could barely speak English. She was not particularly attractive, a peasant girl trying to support her family He spent all his time with her, he fell in love with her--awkwardly informally, but totally. At the end of his twelve months in Vietnam he went home, divorced his beautiful, intelligent, and socially correct wife and then went back to Vietnam and proposed to the bar girl, who accepted. It was a marriage across a vast divide of language, culture, race, and class that could only have been made in war. I am not sure that it lasted, but it would not surprise me if despite great difficulties, it did.

Of course. for every such story there are hundreds. thousands, of stories of passing contacts, a man and a woman holding each other tight for one moment, finding in sex some escape from the terrible reality of tile war. The intensity that war brings to sex, the "let us love now because there may be no tomorrow," is based on death. No matter what our weapons on the battlefield, love is finally our only weapon against death. Sex is the weapon of life, the shooting sperm sent like an army of guerrillas to penetrate the egg's defenses is the only victory that really matters. War thrusts you into the well of loneliness, death breathing in your ear. Sex is a grappling hook that pulls you out, ends your isolation, makes you one with life again.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Not that such thoughts were anywhere near conscious. I remember going off to war with a copy of War and Peace and The Charterhouse of Parma stuffed into my pack. They were soon replaced with The Story of 0. War heightens all appetites. I cannot describe the ache for candy, for taste: I wanted a Mars bar more than I wanted anything in my life And that hunger paled beside the force that pushed it, et toward women, any women: women we would not even have looked at in peace floated into our fantasies and lodged there. Too often we made our fantasies real, always to be disappointed, our hunger only greater. The ugliest prostitutes specialized in group affairs, passed among several men or even whole squads, in communion almost, a sharing more than sexual. In sex even more than in killing I could see the beast, crouched drooling on its haunches, could see it mocking me for my frailties, knowing I hated myself for them but that I could not get enough, that I would keep coming back again and again.

After I ended my tour in combat I came back to work at division headquarters and volunteered one night a week teaching English to Vietnamese adults. One of my students was a beautiful girl whose parents had been killed in Hue during the Tet Offensive of 1968. She had fallen in love with an American civilian who worked at the consulate in Da Nang. He had left for his next duty station and promised he would send for her. She never heard from him again. She had a seductive sadness about her. I found myself seeing her after class, then I was sneaking into the motor pool and commandeering a deuce-and-a-half truck and driving into Da Nang at night to visit her. She lived in a small house near the consulate with her grandparents and brothers and sisters. It had one room divided by a curtain. When I arrived, the rest of the family would retire behind the curtain. Amid their hushed voices and the smells of cooking oil and rotted fish we would talk and fumble toward each other, my need greater than hers.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

I wanted her desperately. But her tenderness and vulnerability, the torn flower of her beauty, frustrated my death-obsessed lust. I didn't see her as one Vietnamese, I saw her as all Vietnamese. She was the suffering soul of war, and I was the soldier who had wounded it but would make it whole. My loneliness was pulling me into the same strong current that had swallowed my friend who married the bar girl. I could see it happening, but I seemed powerless to stop it. I wrote her long poems, made inquiries about staying on in Da Nang, built a fantasy future for the two of us. I wasn't going to betray her the way the other American had, the way all Americans had, the way all men betrayed the women who helped them through the war. I wasn't like that. But then I received orders sending me home two weeks early. I drove into Da Nang to talk to her, and to make definite plans. Halfway there, I turned back.

At the airport I threw the poems into a trash can. When the wheels of the plane lifted off the soil of Vietnam, I cheered like everyone else. And as I pressed my face against the window and watched Vietnam shrink to a distant green blur and finally disappear, I felt sad and guilty--for her, for my comrades who had been killed and wounded, for everything. But that feeling was overwhelmed by my vast sense of relief. I had survived. And I was going home. I would be myself again, or so I thought.

But some fifteen years later she and the war are still on my mind, all those memories, each with its secret passages and cutbacks, hundreds of labyrinths, all leading back to a truth not safe but essential. It is about why we can love and hate, why we can bring forth Fe and snuff it out why each of us is a battleground where good and evil are always at war for our souls.

The power of war, like the power of love, springs from man's heart. The one yields death, the other life. But life without death has no meaning; nor, at its deepest level, does love without war. Without war we could not know from what depths love rises, or what power it must have to overcome such evil and redeem us. It is no accident that men love war, as love and war are at the core of man. It is not only that we must love one another or die. We must love one another and die. War, like death, is always with us, a constant companion, a secret sharer. To deny its seduction, to overcome death, our love for peace, for life itself, must be greater than we think possible, greater even than we can imagine.

Hiers and I were skiing down a mountain in Vermont, flying effortlessly over a world cloaked in white, beautiful, innocent, peaceful. On the ski lift up we had been talking about a different world, hot, green, smelling of decay and death, where each step out of the mud took all our strength. We stopped and looked back, the air pure and cold, our breath coming in puffs of vapor. Our children were following us down the hill, bent over, little balls of life racing on the edge of danger.

Hiers turned to me with a smile and said, "It's a long way from Nam isn't it?"

Yes.

And no.

Let's block ads! (Why?)