In 1726, during a long voyage from London to Philadelphia, a young printer hatched the idea of using a notebook to systematically chart his efforts to become a better man. He set out 13 virtues — including industry, justice, tranquillity and temperance — and his plan was to focus on each in turn in an endless quest for self-improvement, recording failures with a black spot in his journal. The virtue journal worked, and the black marks became scarcer and scarcer.

Benjamin Franklin kept up this practice for his entire life. What a life it was: Franklin invented bifocals and a clean-burning stove; he proved that lightning was a form of electricity and then tamed it with the lightning conductor; he charted the Gulf Stream. He organised a lending library, a fire brigade and a college. He was America’s first postmaster-general, its ambassador to France, even the president of Pennsylvania.

And yet the great man had a weakness — or so he thought. His third virtue was Order. “Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time,” he wrote. While all the other virtues were mastered, one by one, Franklin never quite managed to get his desk or his diary tidy.

“My scheme of Order gave me the most trouble,” he reflected six decades later. “My faults in it vexed me so much, and I made so little progress in amendment, and had such frequent relapses, that I was almost ready to give up the attempt.” Observers agreed. One described how callers on Franklin “were amazed to behold papers of the greatest importance scattered in the most careless way over the table and floor”.

Franklin was a messy fellow his entire life, despite 60 years of trying to reform himself, and remained convinced that if only he could learn to tidy up, he would become a more successful and productive person. But any outsider can see that it is absurd to think such a rich life could have been yet further enriched by assiduous use of a filing cabinet. Franklin was deluding himself. But his error is commonplace; we’re all tidy-minded people, admiring ourselves when we keep a clean desk and uneasy when we do not. Tidiness can be useful but it’s not always a virtue. Even though Franklin never let himself admit it, there can be a kind of magic in mess.

…

Why is it so difficult to keep things tidy? A clue comes in Franklin’s motto, “Let all your things have their places … ” That seems to make sense. Humans tend to have an excellent spatial memory. The trouble is that modern office life presents us with a continuous stream of disparate documents arriving not only by post but via email and social media. What are the “places”, both physical and digital, for this torrent of miscellanea?

Categorising documents of any kind is harder than it seems. The writer and philosopher Jorge Luis Borges once told of a fabled Chinese encyclopaedia, the “Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge”, which organised animals into categories such as: a) belonging to the emperor, c) tame, d) sucking pigs, f) fabulous, h) included in the present classification, and m) having just broken the water pitcher.

Borges’s joke has a point: categories are difficult. Distinctions that seem practically useful — who owns what, who did what, what might make a tasty supper — are utterly unusable when taken as a whole. The problem is harder still when we must file many incoming emails an hour, building folder structures that need to make sense months or years down the line. Borgesian email folders might include: a) coming from the boss, b) tedious, c) containing appointments, d) sent to the entire company, e) urgent, f) sexually explicit, g) complaints, h) personal, i) pertaining to the year-end review, and j) about to exceed the memory allocation on the server.

Regrettably, many of these emails fit into more than one category and while each grouping itself is perfectly meaningful, they do not fit together. Some emails clearly fit into a pattern, but many do not. One may be the start of a major project or the start of nothing at all, and it will rarely be clear which is which at the moment that email arrives in your inbox. Giving documents — whether physical or digital — a proper place, as Franklin’s motto recommends, requires clairvoyance. Failing that, we muddle through the miscellany, hurriedly imposing some kind of practical organising principle on what is a rapid and fundamentally messy flow of information.

When it comes to actual paper, there’s always the following beautiful approach. Invented in the early 1990s by Yukio Noguchi, an emeritus professor at Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo and author of books such as Super Organised Method, Noguchi doesn’t try to categorise anything. Instead, he places each incoming document in a large envelope. He writes the envelope’s contents neatly on its edge, and lines them up on a bookshelf, their contents visible like the spines of books. Now the moment of genius: each time he uses an envelope, Noguchi places it back on the left of the shelf. Over time, recently used documents will shuffle themselves towards the left, and never-used documents will accumulate on the right. Archiving is easy: every now and again, Noguchi removes the documents on the right. To find any document in this system, he simply asks himself how recently he has seen it. It is a filing system that all but organises itself.

But wait a moment. Eric Abrahamson and David Freedman, authors of A Perfect Mess, offer the following suggestion: “Turn the row of envelopes so that the envelopes are stacked vertically instead of horizontally, place the stack on your desktop, and get rid of the envelopes.” Those instructions transform the shelf described in Super Organised Method into an old-fashioned pile of papers on a messy desk. Every time a document arrives or is consulted, it goes back on the top of the pile. Unused documents gradually settle at the bottom. Less elegant, perhaps, but basically the same system.

Computer scientists may recognise something rather familiar about this arrangement: it mirrors the way that computers handle their memory systems. Computers use memory “caches”, which are small but swift to access. A critical issue is which data should be prioritised and put in the fastest cache. This cache management problem is analogous to asking which paper you should keep on your desk, which should be in your desk drawer, and which should be in offsite storage in New Jersey. Getting the decision right makes computers a lot faster — and it can make you faster too.

Fifty years ago, computer scientist Laszlo Belady proved that one of the fastest and most effective simple algorithms is to wait until the cache is full, then start ejecting the data that haven’t been used recently. This rule is called “Least Recently Used” or LRU — and it works because in computing, as in life, the fact that you’ve recently needed to use something is a good indication that you will need it again soon.

As Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths observe in their recent book Algorithms to Live By, while a computer might use LRU to manage a memory cache, Noguchi’s Super Organised Method uses the same rule to manage paper: recently used stuff on the left, stuff that you haven’t looked at for ages on the right. A pile of documents also implements LRU: recently touched stuff on the top, everything else sinks to the bottom.

This isn’t to say that a pile of paper is always the very best organisational system. That depends on what is being filed, and whether several people have to make sense of the same filing system or not. But the pile of papers is not random. It has its own pragmatic structure based simply on the fact that whatever you’re using tends to stay visible and accessible. Obsolete stuff sinks out of sight. Your desk may look messy to other people but you know that, thanks to the LRU rule, it’s really an efficient self-organising rapid-access cache.

…

If all this sounds to you like self-justifying blather from untidy colleagues, you might just be a “filer” rather than a “piler”. The distinction between the two was first made in the 1980s by Thomas Malone, a management professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Filers like to establish a formal organisational structure for their paper documents. Pilers, by contrast, let pieces of paper build up around their desks or, as we have now learnt to say, implement an LRU-cache.

To most of us, it may seem obvious that piling is dysfunctional while filing is the act of a serious professional. Yet when researchers from the office design company Herman Miller looked at high-performing office workers, they found that they tended to be pilers. They let documents accumulate on their desks, used their physical presence as a reminder to do work, and relied on subtle cues — physical alignment, dog-ears, or a stray Post-it note — to orient themselves.

In 2001, Steve Whittaker and Julia Hirschberg, researchers at AT&T Labs, studied filers and pilers in a real office environment, and discovered why the messy approach works better than it seemingly has any right to. They tracked the behaviour of the filers and pilers over time. Who accumulated the biggest volume of documents? Whose archives worked best? And who struggled most when an office relocation forced everyone to throw paperwork away?

One might expect that disciplined filers would have produced small, useful filing systems. But Whittaker and Hirschberg found, instead, that they were sagging under the weight of bloated, useless archives. The problem was a bad case of premature filing. Paperwork would arrive, and then the filer would have to decide what to do with it. It couldn’t be left on the desk — that would be untidy. So it had to be filed somewhere. But most documents have no long-term value, so in an effort to keep their desks clear, the filers were using filing cabinets as highly structured waste-paper baskets. Useful material was hemmed in by well-organised dross.

“You can’t know your own information future,” says Whittaker, who is now a professor of psychology at University of California Santa Cruz, and co-author of The Science of Managing Our Digital Stuff. People would create folder structures that made sense at the time but that would simply be baffling to their own creators months or years later. Organisational categories multiplied. One person told Whittaker and Hirschberg: “I had so much stuff filed. I didn’t know where everything was, and I’d found that I had created second files for something in what seemed like a logical place, but not the only logical place … I ended up having the same thing in two places or I had the same business unit stuff in five different places.”

As for the office move, it was torture for the filers. They had too much material and had invested too much time in organising it. One commented that it was “gruesome … you’re casting off your first-born”. Whittaker reminds me that these people were not discarding their children. They weren’t even discarding family photographs and keepsakes. They were throwing away office memos and dog-eared corporate reports. “It’s very visceral,” Whittaker says. “People’s identity is wrapped up in their jobs, and in the information professions your identity is wrapped up with your information.” And yet the happy-go-lucky pilers, in their messy way, coped far better. They used their desks as temporary caches for documents. The good stuff would remain close at hand, easy to use and to throw away when finished. Occasionally, the pilers would grab a pile, riffle through it and throw most of it away. And when they did file material, they did so in archives that were small, practical and actively used.

Whittaker points out that the filers struggled because the categories they created turned out not to work well as times changed. This suggests that tidiness can work, but only when documents or emails arrive with an obvious structure. My own desk is messy but my financial records are neat — not because they’re more important but because the record-keeping required for accountancy is predictable.

One might object that whatever researchers have concluded about paper documents is obsolete, as most documents are now digital. Surely the obvious point of stress is now the email inbox? But Whittaker’s interest in premature filing actually started in 1996 with an early study of email overload. “The thing we observed was failed folders,” he says. “Tiny email folders with one or two items.”

It turns out that the fundamental problem with email is the same as the problem with paper on the desk: people try to clear their inbox by sorting the email into folders but end up prematurely filing in folder structures that turn out not to work well. In 2011, Whittaker and colleagues published a research paper with the title “Am I Wasting My Time Organizing Email?”. The answer is: yes, you are. People who use the search function find their email more quickly than those who click through carefully constructed systems of folders. The folder system feels better organised but, unless the information arrives with a predictable structure, creating folders is laborious and worse than useless.

…

So we know that carefully filing paper documents is often counterproductive. Email should be dumped in a few broad folders — or one big archive — rather than a careful folder hierarchy. What then should we do with our calendars? There are two broad approaches. One — analogous to the “filer” approach — is to organise one’s time tightly, scheduling each task in advance and using the calendar as a to-do list. As Benjamin Franklin expressed it: “Let each part of your business have its time.” The alternative avoids the calendar as much as possible, noting only fixed appointments. Intuitively, both approaches have something going for them, so which works best?

Fortunately we don’t need to guess, because three psychologists, Daniel Kirschenbaum, Laura Humphrey and Sheldon Malett, have already run the experiment. Thirty-five years ago, Kirschenbaum and his colleagues recruited a group of undergraduates for a short course designed to improve their study skills. The students were randomly assigned one of three possible pieces of coaching. There was a control group, which was given simple time-management advice such as, “Take breaks of five to 10 minutes after every ½-1½ hour study session.” The other two groups got those tips but they were also given much more specific advice as to how to use their calendars. The “monthly plan” group were instructed to set goals and organise study activities across the space of a month; in contrast, the “daily plan” group were told to micromanage their time, planning activities and setting goals within the span of a single day.

The researchers assumed that the planners who set quantifiable daily goals would do better than those with vaguer monthly plans. In fact, the daily planners started brightly but quickly became hopelessly demotivated, with their study effort collapsing to eight hours a week — even worse than the 10 hours for those with no plan at all. But the students on the monthly plans maintained a consistent study habit of 25 hours a week throughout the course. The students’ grades, unsurprisingly, reflected their work effort.

The problem is that the daily plans get derailed. Life is unpredictable. A missed alarm, a broken washing machine, a dental appointment, a friend calling by for a coffee — or even the simple everyday fact that everything takes longer than you expect — all these obstacles proved crushing for people who had used their calendar as a to-do list.

Like the document pilers, the monthly planners adopted a loose, imperfect and changeable system that happens to work just fine in a loose, imperfect and changeable world. The daily planners, like the filers, imposed a tight, tidy-minded system that shattered on contact with a messy world.

Some people manage to take this lesson to extremes. Marc Andreessen — billionaire entrepreneur and venture capitalist — decided a decade ago to stop writing anything in his calendar. If something was worth doing, he figured, it was worth doing immediately. “I’ve been trying this tactic as an experiment,” he wrote in 2007. “And I am so much happier, I can’t even tell you.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger has adopted much the same approach. He insisted on keeping his diary clear when he was a film star. He even tried the same policy when governor of California. “Appointments are always a no-no. Planning ahead is a no-no,” he told The New York Times. Politicians, lobbyists and activists had to treat him like a popular walk-up restaurant: they showed up and hoped to get a slot. Of course, this was in part a pure status play. But it was more than that. Schwarzenegger knew that an overstuffed diary allows no room to adapt to circumstances.

Naturally, Schwarzenegger and Andreessen can make the world wait to meet them. You and I can’t. But we probably could take a few steps in the same direction, making fewer firm commitments to others and to ourselves, leaving us the flexibility to respond to what life throws at us. A plan that is too finely woven will soon lie in tatters. Daily plans are tidy but life is messy.

…

The truth is that getting organised is often a matter of soothing our anxieties — or the anxieties of tidy-minded colleagues. It can simply be an artful way of feeling busy while doing nothing terribly useful. Productivity guru Merlin Mann, host of a podcast called Back To Work, has a telling metaphor. Imagine making sandwiches in a deli, says Mann. In comes the first sandwich order. You’re about to reach for the mayonnaise and a couple of slices of sourdough. But then more orders start coming in.

Mann knows all too well how we tend to react. Instead of making the first sandwich, we start to ponder organisational systems. Separate the vegetarian and the meat? Should toasted sandwiches take priority?

There are two problems here. First, there is no perfect way to organise a fast-moving sandwich queue. Second, the time we spend trying to get organised is time we don’t spend getting things done. Just make the first sandwich. If we just got more things done, decisively, we might find we had less need to get organised.

Of course, sometimes we need a careful checklist (if, say, we’re building a house) or a sophisticated reference system (if we’re maintaining a library, for example). But most office workers are neither construction managers nor librarians. Yet we share Benjamin Franklin’s mistaken belief that if only we were more neatly organised, then we would live more productive and more admirable lives. Franklin was too busy inventing bifocals and catching lightning to get around to tidying up his life. If he had been working in a deli, you can bet he wouldn’t have been organising sandwich orders. He would have been making sandwiches.

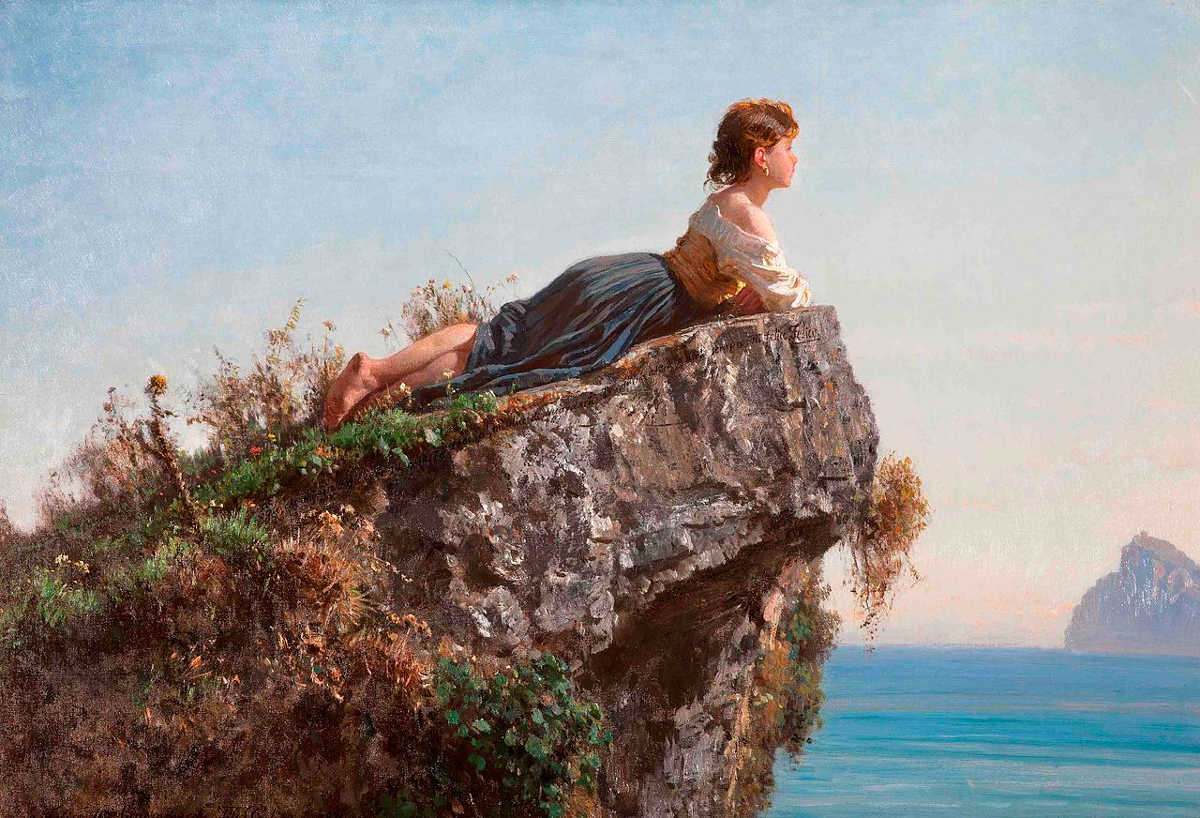

Image by Benjamin Swanson. This article was first published in the Financial Times magazine and is inspired by ideas from my new book, “Messy“. (US) (UK)

Free email updates

(You can unsubscribe at any time)

Email Address

.png)