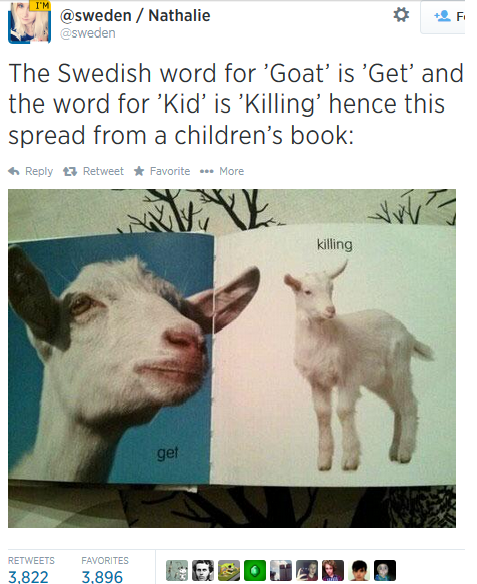

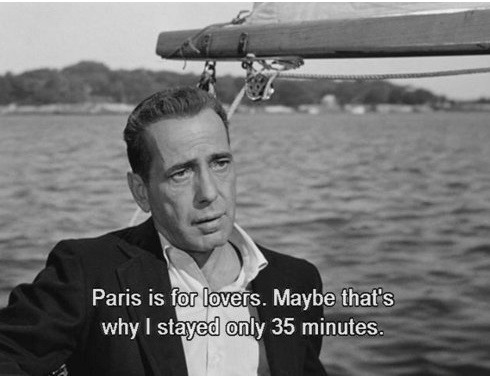

Woody Guthrie and Burl Ives in Central Park, New York, 1940 (courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection)

At the center of Folk City, through January at the Museum of the City of New York, is a clue that the exhibit is more about space than about music. Fixed between the two main rooms is a map of Manhattan and bits of the outer boroughs. The map is sparely drawn, white lines against black, and speckled with red dots pinpointing meaningful sites: venues, record label offices, homes of artists. Most of the dots are downtown, and many are clustered to the south and west of Washington Square Park. In aggregate, the dots add up to something meaningful — but what isn’t exactly clear, at least initially. Consider, though, that the red dots harmonize with the unbroken red walls running fore and aft through the entire exhibit. That’s a lot of red, and patrons might assume it’s a sly joke. The historical New York folk scene, after all, was heavily populated by — and in many ways constructed by — Reds.

But all that red also suggests a unified space, with a gravitational pull. You see a network of red dots on a map, and then take in all the stuff — scratchy recordings and mimeographed fliers and battered guitars — enclosed within the red walls of the exhibit, and it’s as though you’re observing the contents of all the dots, fused together, from the inside out. It’s not the red of left politics, necessarily, but of the bull’s eye: New-York-as-target, drawing people in from across the country and maybe the world, all of them aiming for that red beacon, the glowing red core of a scene. Some from as far away as, say, Hibbing, Minnesota; others who hopped a train from Queens. Walk into the exhibit and you’ll be reminded of one such traveler (the other kind of Red), barreling east toward Manhattan, so sick of Kate Smith on the radio singing Irving Berlin’s star-spangled, god-fearing drivel over and over, so sick of it that he arrived in New York and sat down in a 43rd Street hotel and wrote a little rejoinder. A lifetime later and 60 blocks uptown, those lyrics pave their way into the Folk City exhibit, appearing as massive white text stretching down the length of a brilliantly red floor: This land is your land, this land is my land, from California, to the New York island …

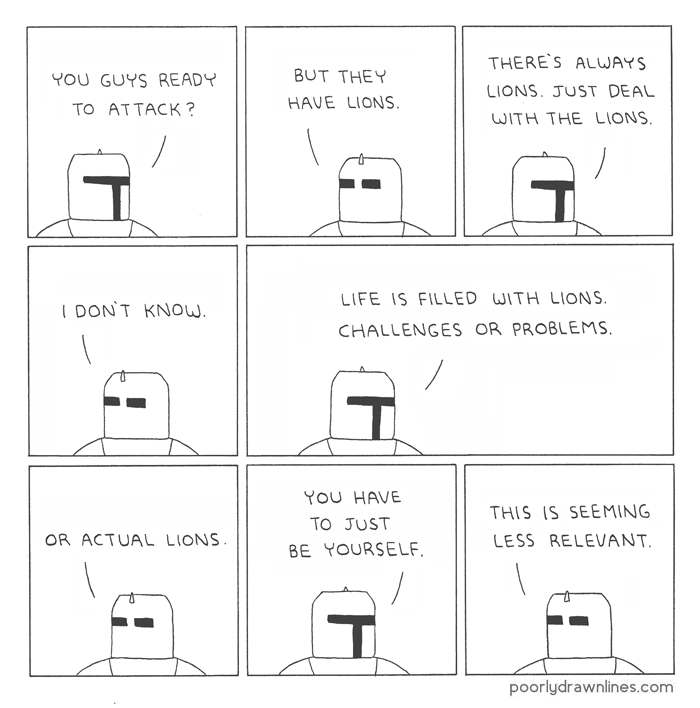

Installation view of ‘Folk City’ at the Museum of the City of New York (image courtesy Museum of the City of New York)

Which is to say: New York became Folk City because a cultural infrastructure, a network of spaces, and the activity within and among them, allowed it to happen. The Folk City exhibit rightly, smartly emphasizes this idea. Sure, it’s about the music, but you can also feel an unsentimental preoccupation with infrastructure, not sound, in the cool uniformity of the red-white-black color scheme; the instruments in their angular display cases; the recordings transmitted through headphones at listening stations — even the ‘Gerdes Folk City’ sign suspended from the ceiling. The exhibit is not about the music per se, or the paraphernalia associated with it, but about the interlocking mechanisms that produced the scene: the record labels (Folkways, Vanguard, Elektra), clubs (The Bitter End, The Gaslight), publications (Sing Out! plus an ocean of fliers, programs, songbooks), and communal spaces (Washington Square Park, Izzy Young’s Folklore Center), all glimpsed through the photographs, printed matter, recorded songs, moving images, and artifacts — the wreckage and relics of the folk revival — that are on display.

Across the river, at Brooklyn’s Interference Archive, is another exhibit concerned with music and politics, and, indirectly, with space. if a song could be freedom…Organized Sounds of Resistance recalls Folk City, too, in the way it offers patrons the chance not only to view but to hear the exhibit, by way of a turntable, tablet, and crate of albums in the center of the room; online playlists; and a 7″ record pressed for the occasion. But instead of documenting a historical space, as Folk City so ably does, if a song could be freedom… conjures up a kind of speculative space, seemingly outside of history. It is a realm of swirling associations, concerned not with infrastructure but with surfaces: namely, the surfaces of albums, lots of them, spread across two adjoining walls — “political” albums in the broadest sense of the word, broad enough so that the very idea of political music is tested and examined. Some are expected (The Clash, Public Enemy, denizens of Folk City) and some are hardly known. Instead of scanning the exhibit album-by-album, catalogue in hand, like a vinyl geek at a record fair, it’s more satisfying to sit back, relax your eyes, and let the affinities and tensions emerge from the entire artwork. That way, you build your own interpretative infrastructure, which is perhaps the most radical aspect of an exhibit that forcefully celebrates radical politics.

Original Manuscript of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” 1962 (click to enlarge) (courtesy Museum of the City of New York, private collector)

Many of the albums display human faces, and my eyes were drawn to those first, whether iconographic (Che Guevara, Malcolm X) or anonymous. The broadly smiling face of Victor Jara is hard to miss, and a reminder that political music is no trifle — Jara was executed after the US-backed Pinochet coup in Chile, in 1973. I felt an echo of Folk City, where, after walking through the door, you see two grainy newspaper clippings, blown up and reproduced on the wall, announcing Pete Seeger’s battle with the McCarthyite witch hunt. That feeling of confrontation suffuses if a song… most visibly on albums produced by communist, anarchist, and socialist groups (there’s a striking collection from Italy and Portugal) but also in the cut-and-paste aesthetics of punk and hardcore albums, or ones inspired by Black liberation movements. In fact, there are more weapons here than instruments; guns and fists outnumber guitars by a considerable number. Some of these albums document or celebrate actual armed liberation struggles; elsewhere, the guns are a kind of bluster, like visual propaganda. But all that weaponry has the unexpected effect of lending power to images of instruments, charging them with meaning: Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s saxophone, wielded toward an unseen oppressor; Phil Ochs’s guitar case, which perhaps, as in a gangster film, contains something other than a guitar…

The exhibit, and the Interference Archive, is emphatically a project of the left, but if a song… doesn’t tell you what to think about the fraught relationship between politics and music. And yet the exhibit is unwavering in the impression that music, somehow, is central to struggles for human emancipation. Scattered through the collage of albums are testimonials submitted by various people, and one, below the riot grrrl band Bikini Kill’s album Pussy Whipped, is from a woman who encountered that album after she and her family emigrated from Peru to New York, by way of crossing the US-Mexico border. At the time she was angry, disoriented, and poor, but the album taught her that anger might be OK, might even be useful — that it might be essential for struggle. Perhaps this is the meaning behind a Woody Guthrie quotation I noticed back in Folk City — not the enormous, famous lyrics that usher you through the entrance, but the smaller words above his portrait: “The world is filled with people who are no longer needed — and who try to make slaves of all of us, and they have their music and we have ours.”

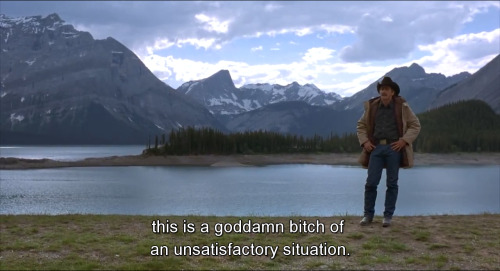

Installation view of ‘if a song could be freedom…Organized Sounds of Resistance’ at Interference Archive (image courtesy Interference Archive)

Sure enough — and Guthrie’s declaration would have been obvious, back then, to many of New York’s folk revivalists, who chose to perform and perpetuate a kind of music that emerged out of the American vernacular, out of the vast laboring classes. Folk music and all its trappings were indicators of, as the song puts it, which side they were on. But thinking through the decades ahead, and through the wider realm of popular music, that dichotomy, between “their music” and “our music,” becomes less stable. And standing before the diversity of albums in the Interference Archive, that division breaks down completely. Who, exactly, is the “we”? And what makes this music “ours”? And what music? And toward what end? These are the questions if a song could be freedom… so artfully poses — not to provide answers, but to lob them into the world like screaming red flares, one after another, requiring attention, attention, attention.

Folk City continues at the Museum of the City of New York (1220 5th Ave, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through January 10. if a song could be freedom…Organized Sounds of Resistance continues at Interference Archive (4, 131 8th St, Gowanus, Brooklyn) through September 6.