He refused to get off the bus. Every finger clamped down on the vinyl seat cushion, legs squeezed tight to chest. He knocked his head against his knees, reeling back, smashing into the seat in front of him. The situation bordered on tantrum. Part of me was trying to join with the others to convince him to stand, yet the other distinctly acknowledged he had good reason to protest. I feared what today would ask of us. We would be paddling through Class Three whitewater rapids, thirteen miles, snowmelt cold, high water June on the Arkansas River. The side of the bus read Colorado School for the Blind. They were high schoolers who had recently lost their vision due to genetic disease, accidents. The group leader stroked the crown of the boy’s head, a ring of keys tinkling at her belt. The raft guides plea-bargained with sodas in the office, promising lunchtime swimming opportunities. What we could not guarantee is that it would all be okay.

My boss Chuck had called a meeting of the guides earlier that morning, recommending, “Don’t act like idiots out there.” We sat on bruised white lawn chairs in the cement office. Defunct clock nailed to the wall. The office was located in the back of the Gunsmoke Truck Stop, eighteen-wheeler semis huffed and chugged beyond the smudged glass door. Earlier that week,  I’d gone out on a friend’s raft, closing my eyes, trying to imagine what it’d feel like to be in the center of thrashing waves and complete darkness. As soon as the raft took a drop over a boulder, my eyes would pop open, gasping for the clarity of light.

I’d gone out on a friend’s raft, closing my eyes, trying to imagine what it’d feel like to be in the center of thrashing waves and complete darkness. As soon as the raft took a drop over a boulder, my eyes would pop open, gasping for the clarity of light.

It was my friend Adam who convinced the boy to depart from his gripped posture and ease down the aisle. He swept his cane in front of him, metal tip scraping the grated bus floor. The other students followed behind, carrying Hawaiian-print beach towels. I stepped off the bus, Chuck was chatting with Patty, the group’s leader.

“Oh yes, our buses have seen some wear as well. First the schools have them, then the churches, then the prisons, and then the rafting companies,” he said, shaking her hand. I had a flash of what our company might look like from this woman’s eyes. Here we were in a ramshackle mountain town, behind a back highway travel plaza, orange porta-potty with door ajar in the parking lot, Chuck’s pronounced limp and duct-taped glasses, Adam’s omnipresent Marlboro musk, my hair matted to a solid mass from sleeping in a tent next to the river. We were tanner than anyone should be.

“The kids are excited. They might not tell you, but I think they’re excited,” Patty said. She wore a low, utilitarian ponytail and the not enough hours in the day wince frequented by nonprofit workers. The students were part of a weeklong summer camp designed to help them adjust to vision loss. They would listen to speakers, weave bracelets, put on a theatre production, and hike the back hills of Colorado Springs. A whitewater rafting trip was the culminating experience, a chance to push past fear and build that elusive self-confidence all summer camps proclaim. I would be the only sighted person in my raft.

Chuck held open the office door and the students moved past him in pairs, whispering about the day ahead. I disappeared into the wetsuit room, holding my breath. Towers of used wetsuit booties unfurled a deep, sour smog of foot sweat. Sizes were scratched in black sharpie on the heels. Blue helmets nested into each other in a cardboard box. The students appeared at the doorway, reporting shoe and wetsuit sizes. I wanted to get to know them, establish some common ground before the trip, but I wasn’t sure what to say. I feared being overly helpful to the point of insult, or conversely, neglecting to be clear and amplifying the unknown.

A girl with streaked blonde hair and Minnie Mouse crop top was next, holding a cellphone between her painted nails. A living product of Forever 21, on-beat with the current summer season. Did she ask someone whether her outfit matched each morning? Could she trust the response? A glaze of glittered chapstick smeared across the edges of her lips.

Could she trust the response? A glaze of glittered chapstick smeared across the edges of her lips.

“I’m going to need a different wetsuit. This one smells like piss,” she said, sticking the wetsuit back through the window. At first I nodded, then articulated yes, okay yes, and went to find another. I handed it to her.

“No way. This one smells like piss too.”

Chuck was holding court behind the desk, doling out waivers and punching cash register keys. The guides helped students hold cracked plastic pens to dashed black lines, the ritual pressing down of signatures, legal small print unmentioned. Others hopped and stepped into wetsuits at all corners of the office, steadying their hands on t-shirt racks. Our guide photos, testimony of our general immaturity, were tacked to a corkboard. In Adam’s shot, he waved his paddle overhead, while a rapid raged below. Others had their guide sticks drawn like air guitars. There was one of Chuck ducking as a wave knocks his hat off in a flash flood, the Arkansas River turned the texture of a root beer float. Torn-down trees spun in the muddy rush.

Patty stared up at the olive parachute hanging above the front desk.

“Young, wild years,” Chuck said, motioning up at it with a pencil. He was one of the original pioneers of skydiving, hitchhiking ten-dollar airplane rides at a military base in the sixties.

“Okay, well, as long as they all stay in the raft,” Patty said, scanning over the students.

“You’re in good hands,” Chuck said.

I looked down at my hands. They were shaking.

*

It wasn’t so simple as to load up the raft, students, and set sail. The guides had to make a quarter mile journey down a steep, rocky hill to the river. We hoisted the rafts to our shoulders, heaving lunch coolers tied with figure eight knots, stuttering over loose gravel. Chuck was giving a long, excruciatingly detailed Safety Talk. It was a barrage of “What if” statements: What if you drop your paddle in the river? What if the raft is wedged on a rock? What if you tumble out of the boat into a rapid? What if you are then sucked under the raft and cannot find your way out? What if your guide falls out? What if you are pinned face-first to a log underwater? By the end of the talk, kids had their hands over their mouths. The boy who refused to get out of the bus was tugging on the side of Patty’s cargo shorts. Adam had given up on the talk and chain-smoked, trails of smoke drifting in the purple light. He lived behind the library in a camper called the Raw Dog and had done a few years in the Marines, which meant he was pretty tough and could tie knots better than the rest of us. Chuck proceeded to splay out, belly-down on the ground, clutching one hand up on the raft’s yellow rope, the other waving madly in the air, yelling, “I’m here! I’m here!” as a demonstration of what not to do if the raft flips over.

We broke off into our raft crews and the blonde girl with braces and legitimate reservations about wetsuit scents was assigned to my group. Her name was Emily. She perched on the edge of the raft, holding the hand of a girl with curly red hair. There were six students who would be responsible for paddling the raft. Two pretty girls, wearing gold earrings and bracelets, sat in the back, somehow sequestering themselves from the rest of the group as cool kids can uniquely do, leaning into conversation concerned only with each other. A boy who introduced himself as Matthew had dyed black hair and the pale complexion of the Great Indoors.

“The big thing we need to do today is paddle together. I’ll be steering and calling commands and then you shout back as you paddle forward,” I said.

This call-and-response was a crude system for an entire day of paddling, but it would have to do. I usually told paddlers to watch the person in front of them to stay in sync. It was crucial that we stuck together on our strokes or the raft would veer to one side or end up powerless, smacking against rocks. And I did not want any of these kids to go in the drink. I had no idea if I’d be able to recover them once the river carried them away. We practiced shouting back and forth, “Forward two strokes! Back paddle once!” Our paddles slicing through the breezeless afternoon air. Whatever would happen out there, would happen together, all of us shouting away like an army platoon. I promised the group I’d warn them when big rapids were coming, and they promised me they would keep paddling even if they were scared.

*

People say they go rafting for the thrill, the waves, the escape. I’ve always been in it for the air and space. In the river canyon, the breeze carries hints of Juniper and Pinyon pine, branches waving in the wind on the bank. No competing exhaust fumes or curdled municipal garbage. Dusty orange cliffs rose to vertigo heights, 100 feet, 200 in another section. The river collected sticks and pine needles; armless logs found speed, spreading brief bubbles over the surface. I didn’t point out the Merganzer ducks picking insects from eddy pools. I didn’t point out the silhouette of an old man’s face on the curved canyon wall. We paddled along, shouting our paddle commands, the rhythm of our voices a uniting chant.

Emily kept asking about another raft, carrying a boy named Kyle. “Is it close to us? Can you see him?” Young love. As I listened to the students talk, it sounded like any other summer camp, with the cliques and crushes, leaders and followers. We relaxed in the flat water before the rapids, but I kept reading the river. The main pursuit of being a raft guide is reading the river, which means finding the line, the strongest part of the current. In even the most tumultuous whitewater sections, the kind where water blasts against rocks, spraying a rooster tail high in the air, amidst cyclones, there is a line of passage.

Matthew, from behind a curtain of black bangs, began announcing passing rocks.

“Is that a boulder on the left? And then one maybe twenty feet ahead in the center of the river?” he asked, cupping his hand on his forehead to squint through the sun.

He’d mentioned earlier that he had Congenital Retinal Deficiency, which meant he was losing his vision daily and would eventually go blind, but could still make out shapes. He’d asked to sit in front.

“You’ve got it,” I said, paddling forward. He smiled as if he’d won something.

When we were still a river bend away, the students heard the first rapid approaching in the distance. It’s named Pinball and that’s the perfect description for how it feels to go through it, raft zinging between the unavoidable rock garden. The entrance is guarded by two flipper rocks, each fifteen feet long and fifteen feet high, sticking straight out of the river. The move was to cut between these rocks, plunk the raft into a hydraulic hole, paddle your way out, and then face the rock garden.

“There’s either a waterfall up ahead or a god damn train,” the red-haired girl said, grabbing onto the rope with both hands, abandoning her paddle. And I really, really needed them to paddle.

I watched the backs of the blue helmets, how they rose up and down as the raft flexed over the rushing waves. The river narrowed, water boiled and morphed over the flipper rocks. Prickly pear cactus specked the riverbank with spines like upturned tacks. I looked for the line, that narrow ridge of passage. The students dug in their paddles as we skirted between the flipper rocks, the raft diving into the hydraulic hole.

Thwack, thwack, thwack, something nailed me in the head, dinging my helmet. Thwack.

“Shit, oh my god!” I yelled, struggling to keep turning the raft straight.

The students snapped around asking what what what. The raft turned sideways and hit a rock. I’d forgotten to strap down their canes. Thwack, as another hit me in the head. I called forwards and we righted the boat, snaked between the remaining boulders, and popped out on the other side.

*

Without additional incident, our rafts pulled off to a beach for lunch. It was a spot called The Zoo, named for the boulder formations shaped like hippopotamus, crocodile, and an elephant’s splintered butt. I began pulling the knots from the coolers, hands shaking in the cold water collected on the raft floor. I realized the students were just sitting there, waiting with paddles crossed over laps, and I’d need to help them onto shore. I led each of them to the charred fire circle, where they sunk down into the sand and leaned against logs.

The guides hauled the coolers and collapsible tables from the rafts, eager for picnic mode. A twenty gallon jug of water teetered on a rock, sleeve of plastic cups tied to the handle. Chuck gave a short sermon on dehydration, “the silent killer.” Patty was on a sunscreen tirade, blobbing out dollops to kids, requiring that they hold out cusped hands as she passed. Emily was smearing hers in a circular motion, the white cream streaking her bangs.

The guides set to chopping onions, slicking turkey meat to a tray, opening pickle jars and hearing the manufacturer’s pop. Chuck whistled as he sliced apples. This was when the guides regrouped, analyzing the previous night’s parties and gossiping about our consistently peculiar paddling crews. Last week we had a senior citizen’s social club. The normally three-hour trip took six hours on account of collective arthritis. The week before was a construction crew of entirely Spanish-speaking workers, rafting as a gift from their boss. My raft had been charging straight for a granite wall and in lack of a proper Spanish equivalent for “Major impact coming, giant rock, holy hell”, I’d yelled out “Explocion!” and all the workers leapt to the floor of the raft, covering their heads.

“You guys making it out there?” I asked.

“Had a girl that would not stop crying, knelt on the bottom of the raft and sobbed. Tried to sing to cheer her up. Bad idea,” Adam said, untwisting the coated yellow wire from the bread’s plastic bag.

“They’re better paddlers than most of the crews I’ve had this year,” I said.

“I think that’s what fear does,” Adam said.

I wondered about fear and rafting as a means of confrontation. Patty kept using the word “overcome” to declare the day’s mission. It was as if fear were a runaway criminal that needed to be seized and tackled to the ground. Both the raft guide and the customer faced respective fears: fear of leading and fear of being led. Both were logical. There had been three deaths on the river that season; undercut rocks created caverns that could trap and drown. Some had strokes from immersion in shockingly cold water. Fear turns out to be persistent, and whitewater will always churn with threat. The important part seemed to be getting in the ring with it. The dare, the dice roll. An acknowledgement of danger, and yet, the continuation of the deed.

The students moved through the lunch line, stroking the slices of meat and cheese to discern what each tray held. Adam elbowed me. The guides ate last and our sandwiches shone with fingerprints. Patty flicked back and forth between students, squeezing out mustard and distributing napkins. I took a seat in the sand with my raft crew. Emily was avoiding direct confrontation with the boy she’d been tracking, but kept asking for updates on what he was doing.

“It sounds like he’s talking about some game?” I reported.

“Oh yeah, no surprise. He’s obsessed with video games even though he can’t play them anymore,” she said.

Emily told me that the best part of camp had been getting away from her parents. She described getting Retinis Pigmentosa last year, noticing the blackboard at school getting blurry, and even falling down the stairs one day.

“Now I have to go everywhere with my mom. She even drops me off in front of school in a freaking van,” she said.

“High school is when you want to break away from your parents, so I get that,” I said.

“I’m starting to get better at using my cane. I’ve been going on walks around my neighborhood by myself,” she said. The act of following the cane’s black tip, raking it across the path to find an opening, reminded me of picking a line on the river. Even as rapids crashed on either side, the right line would guide you to safety.

“I want to become more independent, but stepping outside and knowing that if I cross the street at the wrong time I could get hit by a bus, well, that’s intense,” she said.

Emily asked if I’d take her to the bathroom. I stood up and stretched out my hand, she put hers in mind and I helped pull her up. The munch and rustle of lunch rolled on behind us, everyone worshipping the solid ground, a sweet breeze cutting through the canyon. She set down her water bottle, dusted the sand off her wetsuit. She rejoined my hand so easily, trusting me to lead her, over the rotting logs, around the yucca patches, across the roots of cottonwood willows. Emily squatted behind a Pinyon pine tree and I gazed at the river turning past.

*

Three more miles to go. We’d made it through Sidell’s Suckhole, Raft Ripper, Zoom Flume, and were about to approach Graveyard. There had been no major mishaps, except when another company’s raft came by to start a friendly splash war and was confused when the teens didn’t splash back, but winced and drew away. I called forward strokes to make a quick, polite exit.

As we neared Graveyard’s entrance, the students’ vigor had been drained by the day of paddling, morale dragged. They lazily pulled at the water. Matthew was twisting around to take pictures, “I know. It’s weird. My mom wants them.” The raft didn’t have enough horsepower, angling hard to the right. I yelled for more strokes. My crew gave a weak chant, making small dips with their paddle blades. Whiplash shook us on impact, bodies pounding forward. A wave swamped the left side of the raft and Emily was out. Her hands swatting the air, flying backwards, paddle skidding onto the boulder. The river absorbed her, water swept to erasure. The moment held frozen until her blue helmet peaked to the surface, her head lurching as the lifejacket pillow tipped her face skyward.

Whiplash shook us on impact, bodies pounding forward. A wave swamped the left side of the raft and Emily was out. Her hands swatting the air, flying backwards, paddle skidding onto the boulder. The river absorbed her, water swept to erasure. The moment held frozen until her blue helmet peaked to the surface, her head lurching as the lifejacket pillow tipped her face skyward.

“Everyone paddle!” I urged my crew, but they kept panicking, “Who went out?” Adam blew his whistle and it made the squeal of a hawk. Emily’s helmet rocked in the waves. She was cruising on her back, making no resistance, sweeping further and further from our raft.

“Flip over and swim to the sound of my voice! You’ve got to flip over!” I shouted as the current pulled her under the waves. I yelled her name and so did the kids as they paddled with sweat and gusto; the whole raft lit up with Emily’s name. She turned her head, then one shoulder dropped down as she flipped to her stomach. Stroke by stroke, we got closer. I reached out and grabbed the lapel of Emily’s lifejacket. I threw down my paddle and bent my knees to the side of the raft, yanking her upward. The river let out a whooshing as she surged up from the water. We landed on the floor of the boat.

“You made it back,” I said, breathing hard.

She was shivering, spitting, coughing out water. Her lips were puffy and purple. I checked her arms and legs for signs of trauma. The red-haired girl was crying, but wiping the tears away quickly with the back of her hand. Matthew was taking pictures.

“I’m back, yeah, I’m back,” Emily said. “It felt like being in a dark room that is completely wind.”

It sounded almost too poetic, too lucid for a high schooler, but when immersed in the throws of an indifferent river with only one’s self and one’s boldness and one’s fear, reflection unfolds. Patty was consoling the students on her raft. Chuck clapped.

The line appeared. We went.

***

Rumpus original art by Elizabeth Schmuhl.

Related Posts:

goddamn if Vancouver doesn't have a thriving Satanic art scene.

goddamn if Vancouver doesn't have a thriving Satanic art scene.

It's the job of a security researcher to figure out how the company they are working for could be compromised. Apparently that now means using a drone sniff out vulnerabilities a few dozen feet off the ground. The Aerial Assault drone houses a rasp...

It's the job of a security researcher to figure out how the company they are working for could be compromised. Apparently that now means using a drone sniff out vulnerabilities a few dozen feet off the ground. The Aerial Assault drone houses a rasp...

Back in May, the Internal Revenue Service said thieves nabbed info for 100,000 people through its transcript website. Today the agency increased that number by an additional 200,000 folks, bringing the total number of potential cases to 334,000. Us...

Back in May, the Internal Revenue Service said thieves nabbed info for 100,000 people through its transcript website. Today the agency increased that number by an additional 200,000 folks, bringing the total number of potential cases to 334,000. Us...

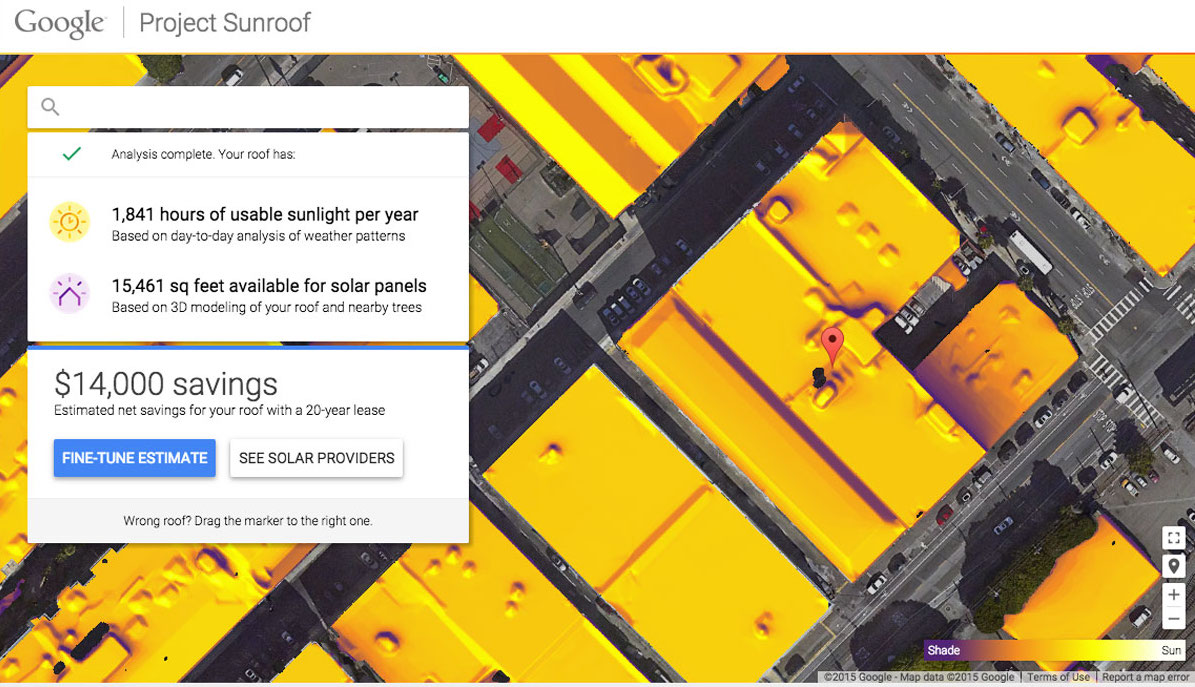

Adding solar panels to your roof can be frustrating, since it's often difficult to know if your home receives enough light to justify the investment. Google Maps, however, has satellite, navigation and sunlight data for every property in the world,...

Adding solar panels to your roof can be frustrating, since it's often difficult to know if your home receives enough light to justify the investment. Google Maps, however, has satellite, navigation and sunlight data for every property in the world,...

India's space agency revealed new photos of a prominent canyon on Mars and showed that it's getting a lot out of a cheap, experimental mission. Images from the nation's Mars Orbital Mission, aka "Mangalyaan," show part of the 62 mile wide and 317 m...

India's space agency revealed new photos of a prominent canyon on Mars and showed that it's getting a lot out of a cheap, experimental mission. Images from the nation's Mars Orbital Mission, aka "Mangalyaan," show part of the 62 mile wide and 317 m...

Despite doubts about the effectiveness of US drone airstrikes in war-torn nations, the Pentagon wants to dramatically increase them. An unnamed official told the WSJ that military commanders intend to bump the number of daily flights by 50 percent....

Despite doubts about the effectiveness of US drone airstrikes in war-torn nations, the Pentagon wants to dramatically increase them. An unnamed official told the WSJ that military commanders intend to bump the number of daily flights by 50 percent....