The Nightly Show, April 16, 2015

*hand movements*

Burly.ThurrLooks like NDT believes in aliens, you skeptics. Do you want to question his Authori-tay?

Burly.ThurrFking Oz.

You'll have heard that a group of physicians has written a public letter to Columbia University asking why Dr. Oz is still on the faculty there. Here's the text, and it includes some heartwarming stuff:

. . .We are surprised and dismayed that Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons would permit Dr. Mehmet Oz to occupy a faculty appointment, let alone a senior administrative position in the Department of Surgery. . .

. . .Dr. Oz has repeatedly shown disdain for science and for evidence-based medicine, as well as baseless and relentless opposition to the genetic engineering of food crops. Worst of all, he has manifested an egregious lack of integrity by promoting quack treatments and cures in the interest of personal financial gain.

Thus, Dr. Oz is guilty of either outrageous conflicts of interest or flawed judgements about what constitutes appropriate medical treatments, or both. . .

It goes on in that vein, and I have to say, I basically agree with every bit of it. I have a good amount of contempt for Oz himself, and that has only increased with time. Columbia, or parts of it, may well be fine with having such a famous, high-profile person associated with the school, but Dr. Oz's fame rests on such a shabby foundation. He spouts nonsense to people who don't know any better - is that such a thing to be proud of?

Columbia is taking an academic-freedom, freedom of speech approach to this request, and Oz himself has said that he'll respond on his show. And I'm sure that we're going to hear oh, so much about bringing in all points of view, and being inclusive, and having an open mind, and providing information to the public (and don't they have a right to that?), and much more in that style. There will probably also be a tone of martyrdom - they're out to get him! - and perhaps a few hints about various "interests" with "agendas" that are behind these baseless attacks.

But I would happily sign a statement requesting that Dr. Oz be shown the door - several doors, at speed - and my only agenda is that I think he peddles sensationalist crap for fame and money. Listening to Dr. Oz is all too often a way to end up less informed than when you started, and full of ideas that have no real basis in fact. Remember, this is the man who told a reporter for the New Yorker that "Cancer is our Angelina Jolie. . .we could sell that show every day". Spoken like a man of medical science!

I'm under no illusions that they're going to get rid of him, though. Hey, Columbia sailed right past that green coffee bean nonsense and the Congressional committee grilling. They're not going to worry about some doctors writing a letter. What would get their attention, though, is if some wealthy donors were to start making some noise. Is that going to happen.

Burly.ThurrCrap. Our Leaf is very susceptible to this attack. My 2002 Golf on the otherhand. Good luck getting anything to work.

Last week, New York Times columnist Nick Bilton took to Twitter to let the world know that two kids broke into his car before his very eyes. What made the break-in a little more remarkable was the fact that, according to Bilton, the perps used an electronic device to simply unlock his Toyota Prius, rather than doing things the old-fashioned way with a slim jim, coat hanger, or brick.

Bilton has elaborated on the event in his column, where he postulates that the young miscreants gained entry to his car (and those of several of his neighbors) by amplifying the signal between his keyless entry fob and car. Keyless entry systems typically only communicate with their remote fobs over the distance of a few feet, but he thinks that the gadget is capable of extending this range, fooling the car into thinking that the remote is within range even though it was actually in Bilton's House, about 50 feet away. He arrived at this theory after he consulted with Boris Danev, a Swiss-based security expert:

"It's a bit like a loudspeaker, so when you say hello over it, people who are 100 meters away can hear the word, 'hello,'" Mr. Danev said. "You can buy these devices anywhere for under $100." He said some of the lower-range devices cost as little as $17 and can be bought online on sites like eBay, Amazon and Craigslist.

This isn't the first time that signal repeaters have been linked to car burglaries in California. In 2013, we reported on a similar spate of thefts in Long Beach, California, that left local police 'stumped.' And it’s not the only way of gaining entry to a supposedly secure car; The Register has previously covered devices that can eavesdrop on the signal between a BMW and its remote, allowing miscreants to program a blank remote for later use.

Read 1 remaining paragraphs | Comments

Burly.ThurrWhen airplanes spin out on the runway, I wonder if there's ever a possibility of correcting the spin by turning into it, like in a car. I hope I never have to find out. *crosses fingers*

Something, like nothing, happens anywhere.

Burly.Thurrvia sophia. I'm not an aspiring writer but now i wish i was. what sweet, sweet self-loathing one can feel as an artist or writer. and then get past it... and fall back again. yum.

Maria Popova collects the advice of Cheryl Strayed and uses Strayed’s words to deconstruct motherfuckery.

Invoking the time right before she wrote her first book, when she too was a twenty-something writer plagued by the same fear that she was “lazy and lame,” Strayed recounts how she “finally reached a point where the prospect of not writing a book was more awful than the one of writing a book that sucked”; in other words, she got off the nail.

Burly.ThurrNeed to find that 50% off framing coupon now.

Burly.ThurrAnother win for magical thinking. Er, wait.

On Thursday, Wiccan high priestess Deborah Maynard led the Iowa legislature in prayer. Invited by representative Liz Bennett (make your Pride and Prejudice jokes, please), Maynard was the first Wiccan to deliver the morning blessing.

Burly.ThurrHad never entirely considered this, but I guess it makes sense. Another win for technicality. Since blood gets its red color from hemoglobin, the close cousin of myoglobin, everyone is forgiven for thinking the red liquid from meat was related to blood.

Today I found out the red juice in raw red meat is not blood. Nearly all blood is removed from meat during slaughter, which is also why you don’t see blood in raw “white meat”; only an extremely small amount of blood remains within the muscle tissue when you get it from the store.

Today I found out the red juice in raw red meat is not blood. Nearly all blood is removed from meat during slaughter, which is also why you don’t see blood in raw “white meat”; only an extremely small amount of blood remains within the muscle tissue when you get it from the store.

So what is that red liquid you are seeing in red meat? Red meats, such as beef, are composed of quite a bit of water. This water, mixed with a protein called myoglobin, ends up comprising most of that red liquid.

In fact, red meat is distinguished from white meat primarily based on the levels of myoglobin in the meat. The more myoglobin, the redder the meat. Thus most animals, such as mammals, with a high amount of myoglobin, are considered “red meat”, while animals with low levels of myoglobin, like most poultry, or no myoglobin, like some sea-life, are considered “white meat”.

Myoglobin is a protein, that stores oxygen in muscle cells, very similar to its cousin, hemoglobin, that stores oxygen in red blood cells. This is necessary for muscles which need immediate oxygen for energy during frequent, continual usage. Myoglobin is highly pigmented, specifically red; so the more myoglobin, the redder the meat will look and the darker it will get when you cook it.

This darkening effect of the meat when you cook it is also due to the myoglobin; or more specifically, the charge of the iron atom in myoglobin. When the meat is cooked, the iron atom moves from a +2 oxidation state to a +3 oxidation state, having lost an electron. The technical details aren’t important here, though if you want them, read the “bonus factoids” section, but the bottom line is that this ends up causing the meat to turn from pinkish-red to brown.

Pro-tip: when searching for non-copyrighted pictures for an article, don’t search for “white meat” or really any variation of that on Google Image Search.

If you liked this article and the Bonus Facts below, you might also enjoy:

Bonus Facts:

Expand for References

Enjoy this article? If so, get our FREE wildly popular Daily Knowledge and Weekly Wrap newsletters:

Subscribe Me To: Daily Knowledge | Weekly Wrap

Burly.ThurrIRL context for present day settings of Under Heaven and River of Stars.

Xinjiang is one of those remote places whose frequent mention in the international press stymies true understanding. American photographer Carolyn Drake has come to know the region well, and struggled to break free from its clichés. The summation of her work is Wild Pigeon, an ambitious, beautiful, and crushingly sad book.

Burly.ThurrSeems fishy. For some reason, and this was over ten years ago, i experienced some very negative attitudes toward pot when i studied in sweden for semester. This study seems like a grab for headlines more than legit research.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Burly.ThurrA little trance throwback for Friday afternoon. I was listening to Oakie on Grooveshark: http://grooveshark.com/s/Life+At+New+York+CD+1/4YTrGB?src=5

Burly.ThurrThose girls got me in the last photo. And the little baby feet in the corner. Karl's feet still look like that.

Burly.Thurr"Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace." http://watergate.info/1969/07/20/an-undelivered-nixon-speech.html

Burly.ThurrHorrified at how these were constructed. Blasted through coral and limestone? Gawd.

[Image: Courtesy of Sotheby's].

[Image: Courtesy of Sotheby's]. [Image: Courtesy of Sotheby's].

[Image: Courtesy of Sotheby's].

[Images: Courtesy of Sotheby's].

[Images: Courtesy of Sotheby's].

[Images: Courtesy of Sotheby's].

[Images: Courtesy of Sotheby's]. [Image: The Danish National Maritime Museum by BIG; photo by Luca Santiago Mora via Dezeen].

[Image: The Danish National Maritime Museum by BIG; photo by Luca Santiago Mora via Dezeen].This parcel was used by the Navy Air Station to house its submarine war ships during the Cuban Missile Crisis and has a very colorful and distinct history. Perfect for marine use and development in a great location. Property includes seven finger cut coral canals that are 90 feet wide and over 25 feet deep, plus a deep water basin with dredged entry channel that provides passage to Boca Chica Channel (Oceanside) and Key West Harbor (Bayside).The asking price?

[Images: Courtesy of Sotheby's].

[Images: Courtesy of Sotheby's].Burly.ThurrI'm with stupid.

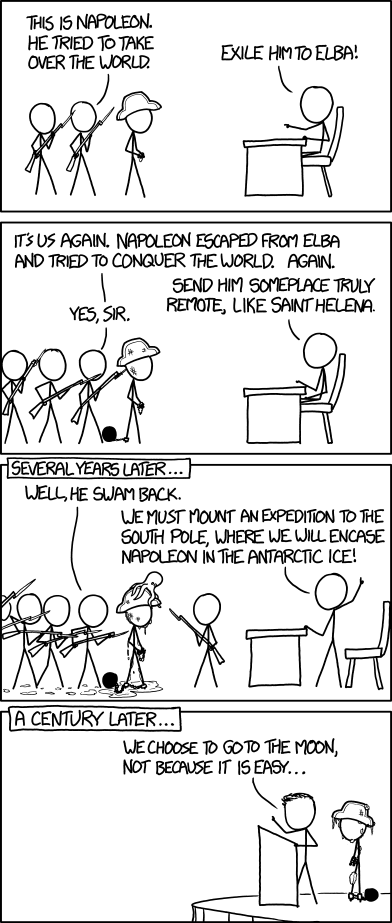

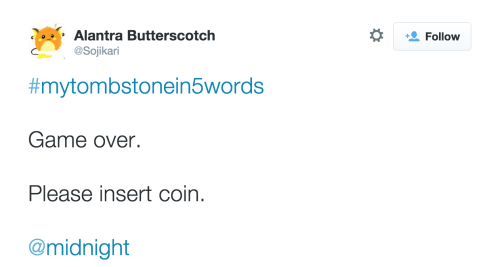

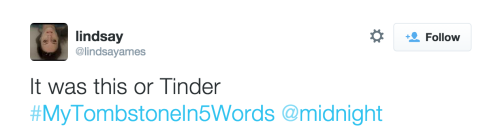

We carved out 10 plots for our favorite Hashtag Wars entries, but only one of these will be Tweet of the Day! Watch tonight’s show to see which wins!

Los Angeles-based musician and composer Andy Rehfeldt (previously) created a great new video in which the band Korn appears to perform a smooth jazz version of their 1999 song “Falling Away From Me“. The music in this remix was arranged and performed by Rehfeldt while being recorded and produced at the Endless Noise studio in Santa Monica, California.

The original version of “Falling Away From Me” for comparison:

Burly.ThurrSame. repost.

James Burke is a legendary science historian who created the landmark BBC series Connections which provided an alternative view of history and change by replacing the traditional “Great Man” timeline with an interconnected web in which all people influence one another to blindly direct the flow of progress. Burke is currently writing a new book about the coming age of abundance, and he continues to work on his Knowledge Web project. In the interview, James Burke says we must soon learn how to deal with a world in which scarcity is scarce, we are more connected to our online communities than our local governments, and home manufacturing can produce just about anything you desire.

We also sit down with Matt Novak, creator and curator of Paleofuture, a blog that explores retro futurism, sifting through the many ways people in the past predicted how the future would turn out, sometimes correctly, mostly not.

This episode is brought to you by The Great Courses. Order Your Deceptive Mind or another course in this special offer and get 80% off the original price.

Thanks to your support on Patreon, you can now read a transcript of my interview with James Burke from that episode. More transcripts are on the way. I hope to add about four a month.

Burly.ThurrSame. Repost for playlist.

Your current browser isn't compatible with SoundCloud.

Please download one of our supported browsers. Need help?

Is your network connection unstable or browser outdated?

Burly.ThurrReposting because my podcast feed broke. Fixed now.

Lacan said that there was surely something ironic about Christ’s injunction to love thy neighbour as thyself – because actually, of course, people hate themselves. Or you could say that, given the way people treat one another, perhaps they had always loved their neighbours in the way they loved themselves: that is, with a good deal of cruelty and disregard. ‘After all,’ Lacan writes, ‘the people who followed Christ were not so brilliant.’ Lacan is here implicitly comparing Christ with Freud, many of whose followers in Lacan’s view had betrayed Freud’s vision by reading him in the wrong way. Lacan could be understood to be saying that, from a Freudian point of view, Christ’s story about love was a cover story, a repression of and a self-cure for ambivalence. In Freud’s vision we are, above all, ambivalent animals: wherever we hate we love, wherever we love we hate. If someone can satisfy us, they can frustrate us; and if someone can frustrate us we always believe they can satisfy us. And who frustrates us more than ourselves?

Ambivalence does not, in the Freudian story, mean mixed feelings, it means opposing feelings. ‘Ambivalence has to be distinguished from having mixed feelings about someone,’ Charles Rycroft writes in his appropriately entitled A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis: ‘It refers to an underlying emotional attitude in which the contradictory attitudes derive from a common source and are interdependent, whereas mixed feelings may be based on a realistic assessment of the imperfect nature of the object.’ Love and hate – a too simple vocabulary, and so never quite the right names – are the common source, the elemental feelings with which we apprehend the world; they are interdependent in the sense that you can’t have one without the other, and that they mutually inform each other. The way we hate people depends on the way we love them and vice versa. According to psychoanalysis these contradictory feelings enter into everything we do. We are ambivalent, in Freud’s view, about anything and everything that matters to us; indeed, ambivalence is the way we recognise that someone or something has become significant to us. This means that we are ambivalent about ambivalence, about love and hate and sex and pleasure and each other and ourselves, and so on; wherever there is an object of desire there must be ambivalence. But Freud’s insistence about our ambivalence, about people as fundamentally ambivalent animals, is also a way of saying that we’re never quite as obedient as we seem to be: that where there is devotion there is always protest, where there is trust there is suspicion, where there is self-hatred or guilt there is also self-love. We may not be able to imagine a life in which we don’t spend a large amount of our time criticising ourselves and others; but we should keep in mind the self-love that is always in play. Self-criticism can be our most unpleasant – our most sadomasochistic – way of loving ourselves.

We are never as good as we should be; and neither, it seems, are other people. A life without a so-called critical faculty would seem an idiocy: what are we, after all, but our powers of discrimination, our taste, the violence of our preferences? Self-criticism, and the self as critical, are essential to our sense, our picture, of our so-called selves. Nothing makes us more critical – more suspicious or appalled or even mildly amused – than the suggestion that we should drop all this relentless criticism, that we should be less impressed by it and start really loving ourselves. But the self-critical part of ourselves, the part that Freud calls the super-ego, has some striking deficiencies: it is remarkably narrow-minded; it has an unusually impoverished vocabulary; and it is, like all propagandists, relentlessly repetitive. It is cruelly intimidating – Lacan writes of ‘the obscene super-ego’ – and it never brings us any news about ourselves. There are only ever two or three things we endlessly accuse ourselves of, and they are all too familiar; a stuck record, as we say, but in both senses – the super-ego is reiterative. It is the stuck record of the past (‘something there badly not wrong’, Beckett’s line from Worstward Ho, is exactly what it must not say) and it insists on diminishing us. It is, in short, unimaginative; both about morality, and about ourselves. Were we to meet this figure socially, this accusatory character, this internal critic, this unrelenting fault-finder, we would think there was something wrong with him. He would just be boring and cruel. We might think that something terrible had happened to him, that he was living in the aftermath, in the fallout, of some catastrophe. And we would be right.

Hamlet, we all remember, wanted ‘to catch the conscience of the king’. For catch the OED has ‘to seize or take hold of, to ensnare, to deceive, to surprise … to take, to intercept … to seize by the senses or intellect, to apprehend’; the term derives originally from hunting and fishing, though it also had in the 16th century our modern connotation of to ‘catch out’. It would have been a very revealing thing to do, to catch the conscience of a king. ‘Conscience’ at the time didn’t only have our modern sense of internal moral regulation but also meant ‘inward knowledge or consciousness’; the dictionary cites a 1611 usage as meaning ‘inmost thought, mind, heart’. To catch the conscience of a king would be radically to expose his most private preoccupations and, in the words of the dictionary, to expose ‘the faculty or principle which judges the moral quality of one’s actions or motives’.

These definitions are interesting not least because they raise the question of just how private or inward or inmost conscience is supposed to be. When we’re talking about a king, or indeed about any authoritative voice, not to mention the religion of the state that the king represented, we might expect that morality would have to be public. And yet these definitions contemporary with Hamlet intimate that one’s morality might also be one’s most private thing: private from the authorities, given that the language of morality was the language of religion, and Hamlet was written at a time of considerable religious division; but also perhaps private in the sense of hidden from the self. One might live as if a certain morality was true without quite knowing what it was. It would be like a morality that had no texts to refer to, nor even knew that reference was required: an unconscious morality, with no discernible cultural moorings. So in speaking one’s mind one might be speaking all sorts of other minds, some recognisable, some not. Hamlet, Brian Cummings writes in Mortal Thoughts, ‘far from speaking his mind, confronts us with a fragmentary repository of alternative selves’. If conscience can be caught – like a fish, like a criminal – it might be part of that fragmentary repository of alternative selves that is like a troupe of actors. The play is the thing in which the conscience of a king – or indeed of anyone, conscience itself being like a king – may be caught, exposed, seen to be like a character. And therefore thought about, and discussed. What does the conscience of the king or of anyone look like? Who, or what, does it resemble? What does it wear? Being able to reflect on one’s conscience – being able to look at the voice of conscience from varying points of view – is itself a radical act (one that psychoanalysis would turn into a formal treatment). If the voice of conscience is not to be obeyed, what is to be done with it?

In The Interpretation of Dreams Freud used Hamlet as, among other things, a way of understanding the obscene severities of conscience. In what seems in retrospect a rather simple picture of a person, he proposed that we were driven by quickly acculturated biological instincts, tempered by controls and prohibitions internalised from the culture through the parents. Conscience, which twenty years later, in The Ego and the Id, Freud would incorporate into his notion of the super-ego, was there to protect and prohibit the individual from desires that endangered him, or were presumed to. In Freud’s view we have conscience so that we may not perish of the truth – the truth, that is, of our desire. Hamlet was illuminating for Freud because it showed him how conscience worked, and how psychoanalytic interpretation worked, and how psychoanalysis could itself become part of the voice of conscience.

‘The loathing which should drive [Hamlet] on to revenge,’ Freud writes, ‘is replaced in him by self-reproaches, by scruples of conscience, which remind him that he himself is literally no better than the sinner whom he is to punish.’ Hamlet, in Freud’s view, turns the murderous aggression he feels towards Claudius against himself: conscience is the consequence of uncompleted revenge. Originally there were other people we wanted to murder but this was too dangerous, so we murder ourselves through self-reproach, and we murder ourselves to punish ourselves for having such murderous thoughts. Freud uses Hamlet to say that conscience is a form of character assassination, the character assassination of everyday life, whereby we continually, if unconsciously, mutilate and deform our own character. So unrelenting is this internal violence that we have no idea what we’d be like without it. We know almost nothing about ourselves because we judge ourselves before we have a chance to see ourselves.

Freud is showing us how conscience obscures self-knowledge, intimating indeed that this may be its primary function: when we judge the self it can’t be known; guilt hides it in the guise of exposing it. This allows us to think that it is complicitous not to stand up to the internal tyranny of what is only one part – a small but loud part – of the self. So frightened are we by the super-ego that we identify with it: we speak on its behalf to avoid antagonising it (complicity is delegated bullying). But in arguing with his conscience, in trying to catch it, with such eloquence and subtlety, Hamlet has become a genius of self-reproach; his conversations with himself and others about conscience allow him to speak in ways no one had ever quite spoken before.

After interpreting Hamlet’s apparent procrastinations with the new-found authority of the new psychoanalyst, Freud feels the need to add something by way of qualification that is at once a loophole and a limit. ‘But just as all neurotic symptoms,’ he writes, ‘and, for that matter, dreams, are capable of being “over-interpreted”, and indeed need to be, if they are to be fully understood, so all genuinely creative writings are the product of more than a single impulse in the poet’s mind, and are open to more than a single interpretation.’ It is as though Freud’s guilt about his own aggression in asserting his interpretation of what he calls the ‘deepest layers’ in Hamlet – his claim to sovereignty over the text and the character of Hamlet – leads him to open up the play having closed it down. You can only understand anything that matters – dreams, neurotic symptoms, people, literature – by over-interpreting it; by seeing it, from different aspects, as the product of multiple impulses. Over-interpretation, here, means not settling for a single interpretation, however apparently compelling. The implication – which hints at Freud’s ongoing suspicion, i.e. ambivalence, about psychoanalysis – is that the more persuasive, the more authoritative the interpretation the less credible it is, or should be. If one interpretation explained Hamlet we wouldn’t need Hamlet anymore: Hamlet as a play would have been murdered. Over-interpretation means not being stopped in your tracks by what you are most persuaded by; to believe in a single interpretation is radically to misunderstand the object one is interpreting, and interpretation itself.

In the normal course of things, tragic heroes are emperors of one idea: they always under-interpret. Hamlet, we could say, is a great over-interpreter of his experience; and it is the sheer range and complexity of his thoughts – his interest in his thought from different aspects – that makes him such an unusual tragic hero. ‘Emerson was distinguished,’ Santayana wrote, ‘not by what he knew but by the number of ways he had of knowing it.’ Freud was beginning to fear, at this moment in The Interpretation of Dreams, and rightly as it turned out, that psychoanalysis could be undistinguished if it had only one way of knowing what it thought it knew. It was dawning on him, prompted by his reading of Hamlet, that psychoanalysis, at its worst, could be a method of under-interpretation. And to take that seriously was to take the limits of psychoanalysis seriously; and indeed the limits of any description of human nature that organises itself around a single metaphor. The Oedipus complex – a story about the paramount significance of forbidden desire in the individual’s development – was the essential psychoanalytic metaphor. Comparing Hamlet with the psychoanalytic readings of Hamlet as an Oedipal crisis would soon more than confirm Freud’s misgivings about the uses and misuses of psychoanalysis. Indeed such readings underline Deleuze and Guattari’s point in Anti-Oedipus that the function of the Oedipus myth in psychoanalysis is, paradoxically, to restore law and order, to contain with a culturally prestigious classical myth the unpredictable, prodigal desires that Freud had unleashed.

So there is Cummings’s distinction between the notion of Hamlet speaking his mind as opposed to his speaking a ‘fragmentary repository of alternative selves’; and there is Freud’s authoritative psychoanalytic interpretation of Hamlet highly qualified by his subsequent promotion of ‘over-interpretation’; and there is Hamlet’s troupe of actors who will perform a play that will be the thing to catch the conscience of a king. And there is of course Hamlet’s question in his most famous soliloquy, in which he tells us something about suicide, and something about death, and something about all the unknown and unknowable future experiences that death represents. And he does this by telling us something about conscience. Or rather, two things about conscience.

The first quarto of Hamlet has, ‘Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,’ while the second quarto has, ‘Thus conscience does make cowards.’ If conscience makes cowards of us all, then we’re all in the same boat; this is just the way it is. If conscience makes cowards we can more easily wonder what else it might be able to make. Either way, and they’re clearly different, conscience makes something of us: it is a maker, if not of selves, then of something about selves; it is an internal artist, of a kind. Freud says that the super-ego is something we make; it in turn makes something of us, turns us into a certain kind of person (just as, say, Frankenstein’s monster turns Frankenstein into something that he wasn’t before he made the monster). The super-ego casts us as certain kinds of character; it, as it were, tells us who we really are; it is an essentialist; it claims to know us in a way that no one else, including ourselves, can ever do. And, like a mad god, it is omniscient: it behaves as if it can predict the future by claiming to know the consequences of our actions – when we know, in a more imaginative part of ourselves, that most actions are morally equivocal, and change over time in our estimation. (No apparently self-destructive act is ever only self-destructive, no good is purely and simply that.) Self-criticism is an unforbidden pleasure: we seem to relish the way it makes us suffer. Unforbidden pleasures are the pleasures we don’t particularly want to think about: we just implicitly take it for granted that each day will bring its necessary quotient of self-disappointment, that every day we will fail to be as good as we should be; but without our being given the resources, the language, to wonder who or what is setting the pace, or where these rather punishing standards come from. How can we find out what we think of all this when conscience never lets go?

If conscience makes us cowards then what is conscience like? Cowardice may be, as the dictionary puts it, the ‘display … of ignoble fear in the face of pain, danger or difficulty’; according to Chambers, a coward may be a ‘pusillanimous person’, someone ‘wanting firmness of mind … mean-spirited’. Cowardice is deemed to be unimpressive, inappropriate, a shameful fear. We are cowardly when we are not at our best, when frightened. But there are acceptable and unacceptable versions of fearfulness, which means we should be fearful in certain ways, and fearful of certain objects. Fear, like everything else, is subject to cultural norms. So if conscience makes cowards, it demeans us; it is the part of ourselves that humiliates us, that makes us ashamed of ourselves. But what if it makes the very selves that it encourages us to be ashamed of? As Hamlet famously tells us, it sometimes torments us by stopping us killing ourselves when our lives are actually unbearable. It can, as Hamlet can’t quite say, be a kind of torturer; even making us go on living when we know, in a more imaginative part of ourselves, that our lives have become intolerable. Conscience, that is to say, can seduce us into betraying ourselves. Freud’s super-ego is the part of our mind that makes us lose our minds, the moralist that prevents us from evolving a personal, more complex and subtle morality. When Richard III says, ‘O coward conscience, how dost thou afflict me!’ a radical alternative is being proposed: that conscience makes cowards of us all because it is itself cowardly. We believe in, we identify with, this starkly condemnatory and punitively forbidding part of ourselves; and yet this supposed authority is itself a coward.

Conscience is intimidating because it is intimidated. We have to imagine not that we are cowardly, but that we have been living by the morality of a coward; the ferocity of our conscience might be a form of cowardice. But what other kind of morality might there be? If we have been living by a forbidding morality, what would an unforbidding morality look like? There are moralities inspired by fear, but what would a morality be like that was inspired by desire? It would, as Hamlet’s soliloquy perhaps suggests, be a morality, a conscience, that had a different relation to the unknown. The coward, after all, always thinks he knows what he fears, and knows that he doesn’t have the wherewithal to deal with it. The coward, like Freud’s super-ego, is too knowing. A coward – or rather, the cowardly part of ourselves – is like a person who must not have a new experience. Hamlet is talking about suicide, but talking about suicide is a way of talking about experiences one has never had before:

Who would fardels bear

To grunt and sweat under a weary life

But that the dread of something after death

(The undiscovered country from whose bourne

No traveller returns) puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of.

Thus conscience does make cowards –

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action.

‘The undiscovered country from whose bourne/No traveller returns’ is also the unknown and unknowable future, ‘bourne’ reminding us that our relation to the future is both a continual being born and something we have to find ways of bearing. One of the ways we bear the unknownness of the future is to treat it as though it was, in fact, the past; and as though the past was something we did know about. (Freud would formalise this idea in his concept of transference: we invent new people on the basis of past familial relationships, as if we knew those people and could use that knowledge as a reliable guide.) There is no expectation that the unknown will be either better than expected, or wholly other than the way it can be imagined.

But talking about conscience – and the prospect of death – gives Hamlet some of his best lines. If conscience doesn’t always feed us our best lines, he suggests, then talking and writing about it may. Conscience, in its all too impoverished vocabulary and its all too serious and suffocating drama, needs to be over-interpreted. Under-interpreted it can only be taken on its own terms, it can only be propaganda (the super-ego only speaks propaganda about the self, which is why it is so boring, and yet so easy to listen to). Something as unrelenting as our internal soliloquies of self-reproach, Freud realised, necessitated unusually imaginative redescriptions. Without such redescriptions – and Hamlet is of course one – the ‘fragmentary repository of alternative selves’ will be silenced. The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune are as nothing compared with the murderous mufflings and insinuations and distortions of the super-ego because it is the project of the super-ego, as conceived of by Freud, to render the individual utterly solipsistic, incapable of exchange. Or to make him so self-mortified, so loathsome, so inadequate, so isolated, so self-obsessed, so boring and bored, so guilty that no one could possibly love or desire him. The solitary modern individual and his Freudian super-ego, a master and a slave in a world of their own. ‘Who do I fear?’ Richard III asks at the end of his play, ‘Myself? There’s none else by.’

Like all unforbidden pleasures self-criticism, or self-reproach, is always available and accessible. But why is it unforbidden, and why is it a pleasure? And how has it come about that we are so bewitched by our self-hatred, so impressed and credulous in the face of our self-criticism, unimaginative as it usually is? Self-reproach is rarely an internal trial by jury. A jury, after all, represents some kind of consensus as an alternative to autocracy. Self-criticism, when it isn’t useful in the way any self-correcting approach can be, is self-hypnosis. It is judgment as spell, or curse, not as conversation; it is an order, not a negotiation; it is dogma not over-interpretation. Psychoanalysis sets itself the task of wanting to have a conversation with someone – call it the super-ego – who, because he knows what a conversation is, is definitely never going to have one. The super-ego is a supreme narcissist.

The Freudian super-ego is a boring and vicious soliloquist with an audience of one. Because the super-ego, in Freud’s view, is a made-up voice – a made-up part – it has a history. Freud sets out to trace this history with a view to modifying it, which meant creating a genealogy that begins with the more traditional, non-secular idea of conscience. Separating out conscience from his new apparently secular concept of the super-ego involves Freud in all the contradictions attendant on unravelling one’s history. To put it as simply as possible, Freud’s parents, and most of the people living in fin-de-siècle Vienna, probably thought of themselves as having consciences; and whatever else they felt about these consciences they were the more or less acknowledged legacy of a religious past, a cultural inheritance. Freud wanted to describe what was, in effect, the secular heir of these religious and secularised-religious consciences, the super-ego.

‘We see how one part of the ego,’ he writes in Mourning and Melancholia, ‘sets itself over against the other, judges it critically and, as it were, takes it as its object.’ The mind, so to speak, splits itself in two, and one part sets itself over the other to judge it. It ‘takes it as its object’: that is to say, the super-ego treats the ego as though it were an object not a person. In other words, the super-ego, the inner judge, radically misrecognises the ego, treating it as if it can’t answer back, as if it doesn’t have a mind of its own (it is noticeable how merciless and unsympathetic we can be to ourselves in our self-criticism). It is intimated that the ego – what we know ourselves to be – is the slave of the super-ego. How have we become enslaved to this part of ourselves, and how and why have we consented? What’s in it for us? And in what sense is the super-ego Freud’s implied critique of the Judeo-Christian religions and their god?

Internally, there is a judge and a criminal, but no jury. Annabel Patterson writes in Early Modern Liberalism of Algernon Sidney, whose ‘agenda was to move the reader gradually to understand that the only guarantor against partisan jurisprudence was shared jurisprudence’. Freud’s agenda in psychoanalysis, continuing in this liberal tradition, was to experiment with the possibility of shared internal jurisprudence. Self-criticism might be less jaded and jading, more imaginative and less spiteful, more of a conversation. The enslaved and judged ego could have more than his judge to appeal to, and the psychoanalyst would be the patient’s ally in this project – suggesting juries, offering multiple perspectives on under-interpreted actions. This, of course, was not possible, at least in quite this way, in a monotheistic religion, or an absolutist state. To whom could the modern individual appeal in the privacy of his own mind? Freud would answer through the experiment of psychoanalysis that there is more to a person – more parts, more voices, more fragmentary alternative selves – than the judge and the judged. There is, in effect, a repressed repertoire. Where judgment is, there conversation should be. Where there is dogma there is an uncompleted experiment. Where there is self-condemnation it is always more complicated than that.

Freud’s super-ego is more than just conscience, although it includes this traditional form. It also has other functions, one of which is – in a limited sense – benign. The super-ego is not only the censor or judge but also the provider and guardian of what Freud calls our ‘ego-ideals’. The ego-ideal, Laplanche and Pontalis write in The Language of Psychoanalysis, ‘constitutes a model to which the subject attempts to conform’. Once again, Freud prefers the multiple view: ‘Each individual,’ he writes, ‘is a component part of numerous groups, he is bound by ties of identification in many directions, and he has built up his ego-ideal on the most vari0us models.’ The ego-ideal is both composite – made up from many cultural models and influences – and divisive. It keeps alternative models at bay, but it can also be surprisingly inclusive. In this ambiguity, which Freud can never quite resolve, he is wondering just how constricted the modern individual really is, or has to be. In making the ego-ideal, at its best, the ego has over-interpreted his culture, beginning with the family; he has taken whatever he can use from his culture to make up his own ideals for himself.

But that other aspect of the super-ego, the censor or judge, Freud believes, is just an internalised version of the prohibiting father, the father who says to the Oedipal child: ‘Do as I say, not as I do.’ The super-ego, by definition, despite Freud’s telling qualifications, under-interprets the individual’s experience. It is, in this sense, moralistic rather than moral. Like a malign parent it harms in the guise of protecting; it exploits in the guise of providing good guidance. In the name of health and safety it creates a life of terror and self-estrangement. There is a great difference between not doing something out of fear of punishment, and not doing something because one believes it is wrong. Guilt isn’t necessarily a good clue as to what one values; it is only a good clue about what (or whom) one fears. Not doing something because one will feel guilty if one does it is not necessarily a good reason not to do it. Morality born of intimidation is immoral. Psychoanalysis was Freud’s attempt to say something new about the police.

We can see the ways in which Freud is getting the super-ego to do too much work for him: it is a censor, a judge, a dominating and frustrating father, and it carries a blueprint of the kind of person the child should be. And this reveals the difficulty of what Freud is trying to come to terms with: the difficulty of going on with the cultural conversation about how we describe so-called inner authority, or individual morality. But in each of these multiple functions the ego seems paltry, merely the slave, the doll, the ventriloquist’s dummy, the object of the super-ego’s prescriptions – its thing. And the id, the biological forces that drive the individual, are also supposed to be, as far as possible, the victims, the objects of the super-ego’s censorship and judgment. The sheer scale of the forbidden in this system is obscene. And yet, in this vision of things, all this punitive forbidding becomes, paradoxically, one of our primary unforbidden pleasures. We are, by definition, forbidden to find all this forbidding forbidden. Indeed we find ways of getting pleasure from our restrictedness.

But how has it come about that we so enjoy this picture of ourselves as objects, and as objects of judgment and censorship? What is this appetite for confinement, for diminishment, for unrelenting, unforgiving self-criticism? Freud’s answer is beguilingly simple: we fear loss of love. Fear of loss of love means forbidding certain forms of love (incestuous love, or interracial love, or same sex love, or so-called perverse sexuality, or loving what the parents don’t love, and so on). We need, in the first instance, the protection and co-operation of our parents in order to survive; so a deal is made (a contract is drawn up). The child says to the parents: ‘I will be as far as possible what you need me to be, in exchange for your love and protection.’ As with Hobbes’s story about sovereignty, the protection required for survival is paramount: everything must be sacrificed for this, except one’s life. Safety is preferred to desire; desire is sacrificed for security. But this supposed safety, in Freud’s version, comes at considerable cost: the cost of being turned into, by being treated as, an object. We are made to feel that we need constant critical scrutiny. We must be cram-packed with forbidden desires, if so much censorship and judgment are required. We are encouraged by all this censorship and judgment to believe that forbidden, transgressive pleasures are what we really crave; that really, essentially, deep down, we are criminals; that we need to be protected primarily from ourselves, from our wayward desires.

What this regime doesn’t allow us to think, clearly, is that we are also cram-packed with unforbidden desires; or that there might be a way for our moral ideals to be something other than forbidding. Just as the overprotected child believes that the world must be very dangerous and he must be very weak if he requires so much protection (and the parents must be very strong if they are able to protect him from all this), so we have been terrorised by all this censorship and judgment into believing that we are radically dangerous to ourselves and others.

The books we read in adolescence often have an extraordinary effect on our lives. They are, among other things, an attempt at regime change. In Freud’s language we could say that we free ourselves of our parents’ ideals for us by using the available culture to make up our own ego-ideals, to evolve a sense of our own affinities beyond the family, to speak a language that is more our own. In the self-fashioning of adolescence, books (or music or films) begin really to take, to acquire a subtle but far-reaching effect that lasts throughout a person’s life. We should, therefore, take seriously Freud’s adolescent passion for Don Quixote, a story about a ‘madman’ – as he is frequently referred to in the book – whose life is eventually entirely formed by his reading, in his case the reading of chivalric romances. He is a man who inhabits, lives in and through, the fictions about knights errant that he has consumed, a fictional character who makes himself out of fictional characters.

As a young man Freud was an avid reader, and was very good at and interested in languages. He learned Spanish, as he wrote to a correspondent in 1923, for a particular reason: ‘When I was a young student the desire to read the immortal Don Quixote in the original of Cervantes led me to learn, untaught, the lovely Castilian tongue.’ This ‘youthful enthusiasm’ was born of a passionate relationship with a schoolfriend called Edward Silberstein. He was, Ernest Jones writes in his biography of Freud,

Freud’s bosom friend in school days, and they spent together every hour they were not in school. They learned Spanish together and developed their own mythology and private words, mostly derived from Cervantes … They constituted a learned society to which they gave the name of Academia Cartellane, and in connection with it wrote an immense quantity of belles-lettres composed in a humorous vein.

An intimacy between two boys that is based on a story about an intimacy between two men, an intimacy that inspires writing and humour and complicity: Don Quixote (not incidentally more or less a contemporary with Hamlet) could be linked in many ways with Freud’s life and the development of psychoanalysis. But there is one thing worth singling out in this text for the purposes of thinking further about unforbidden pleasure, and the often futile unforbidden pleasure of self-criticism: Don Quixote’s infamous horse, Rocinante. In a well-known passage in the New Introductory Lectures, where Freud is describing the relationship between the ego and the id – between the person’s conscious sense of themselves and their more unconscious desires – he uses an all too familiar, traditional analogy (as if to say, psychoanalysis is just a modern version of a very old story). ‘The horse,’ Freud writes, ‘supplies the locomotive energy, while the rider has the privilege of deciding on the goal, and of guiding the powerful animal’s movement. But only too often there arises between the ego and the id the not precisely ideal situation of the rider being obliged to guide the horse along the path by which it itself wants to go.’

I take this ‘not precisely ideal situation’ to be an allusion, whatever else it may be in our over-interpreting it, to Don Quixote; and to what, in several senses, he was led by. If we read it like this the ego is the deluded fantastical knight who, like all realists, is utterly plausible to himself. And Rocinante, in this rather more Beckettian version, is what we call an old nag: this is at once a parody of, and an exposé of, the horse as elemental force. And where does Rocinante go, as Don Quixote is led by his horse? He goes home. But because he is a horse, not a person, home does not mean incest – it just means where he lives. Home had always meant more than incestuous desire; until it was under-interpreted by psychoanalysis. In this pre-Freudian/post-Freudian model – one, perhaps, that Freud repressed in his urge to provide a more scientifically bracing and traditionally religious model – the id is the nag Rocinante, the ego is the mad Don Quixote, and the super-ego is the sometimes amusing, often good-humoured, sometimes down to earth and gullible Sancho Panza. ‘Sancho,’ the critic A.J. Close writes, ‘is proverbially rustic; panza means belly; and the character of the man is basically that of the clowns of 16th-century comedy; lazy, greedy, cheeky, loquacious, cowardly, ignorant, and above all nitwitted.’ What does the Freudian super-ego look like if you take away its endemic cruelty, its unrelenting sadism? It looks like Sancho Panza. And like Sancho Panza, the absurd and obscene super-ego is a character we mustn’t take too seriously.

‘Sancho proves to have too much mother wit to be considered a perfect fool,’ Nabokov writes, ‘although he may be the perfect bore.’ We certainly need to think of our super-ego as a perfect bore, and as all too gullible in its apparent plausibility. We need, in other words, to realise that we may be looking at ourselves a little more from Sancho Panza’s point of view, whether or not we are rather more like Don Quixote than we would wish. We may have underestimated just how restricted our restrictiveness makes us.

Burly.ThurrAw, happy birthday, Vox! They're punching above their age-class, IMHO.

Today is Vox's first anniversary, but it is also the 12th anniversary of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld sending what was perhaps the greatest memo ever written. Titled "issues with various countries," it noted in passing that basically none of the Bush administration's foreign policy initiatives were working well, and asked Undersecretary of Defense Doug Feith to solve all the problems:

Needless to say, none of this got solved.

WATCH: 'Frenemies - a story of Iran, Israel and the United States'

Burly.ThurrSecond axiom: If one is good, five is better.

Burly.ThurrThe mechanistic god of empiricism beat.

Here's a brief article in Science that a lot of us should keep a copy of. Plenty of journalists and investors should do the same. It's a summary of what sort of questions get asked of data sets, and the differences between them. There are six broad data analysis categories:

1. Descriptive. This is the simplest case, where you're just summarizing a data set and describing the totals in it.

2. Exploratory. The next step - you search through the descriptive analysis looking for trends or relationships, with which to develop new hypotheses. No guarantees, of course - you'll have to confirm these with more work.

3. Inferential. This one looks at an exploratory treatment and tried to determine whether those trends are likely to hold up. As the authors say, this is probably the most common statistical workup in the literature - better than randome chance, or not? But it can't tell you why something is happening, of course.

4. Predictive. An inferential study is necessarily done on a large sample (well, it had better be, at any rate, if you're going to infer with much confidence). A predictive analysis uses some subset of the data to predict how individual cases will go. The example from drug development would be the use of biomarkers to predict whether a given patient in a trial will respond to some new investigational drug.

5. Causal. At this level, you're trying to see what the magnitude of changes are across the system when you start changing things - what often gets called the "tone" of the system. What are the most important variables, and what has little effect on the outcome?

6. Mechanistic. With the information at the causal level available, now you can really get down to the nuts and bolts. Change A causes effect B, through this detailed mechanism. We don't see this as much with anything involving biology - there always seem to be exceptions. This is more the realm of engineering and physics, although a lot of time and money is going into trying to change that.

It's only at the causal and mechanistic levels that you can start doing detailed modeling with confidence. That's where everyone would like to be with computational binding predictions, but we don't understand them well enough yet. And think how far we have to go to get predictive toxicology to those levels! We can do that sort of thing on a small scale - for example, saying that a compound that (say) inhibits angiotensin-converting enzyme, to this degree, and with that average half-life in vivo, will be expected to lower X% of a random population's members blood pressure by at least Y%. That's after decades of experience and data-gathering, keep in mind.

But that's not aeronautical engineering. Those folks don't tell you that wing design A will provide at least so much lift on a certain percentage of the airframes it gets bolted on to. Nope, those folks get to build their airframes to the same exact specifications, not just take whatever shows up at the factory needing wings, and those airframe/wing combinations had better perform within some very tight tolerances or something has gone seriously wrong. This is just another way of stating the "built by humans" difference I was talking about the other day.

So some of that data analysis hierarchy above is, well, aspirational for those of us doing drug research. The authors of the Science article are well aware of this themselves, saying that "Outside of engineering, mechanistic data analysis is extremely challenging and rarely achievable.". But that level is where many people expect science to be, most of the time, which leads to a lot of frustration: "Look, is this pill going to help me or not?" We should remember where we are on the scale and try to work our way up.

Burly.ThurrAwesome illuminating share from @wampus. (sorry, @wumpus, i saw fatbob call you that and had to use it.)

One of the most commonly-used pesticides in the world was recently declared a probable cause of cancer—but that doesn't mean what you think, and here are some stick figures to explain it to you.

This video by Andrew Maynard of the University of Michigan's Risk Science Center explains what exactly the word "probably" means in that context (it has a specific definition). It doesn't mean that the substance is a carcinogen and it will probably give you cancer; it means that it's probably a carcinogen that may or may not ever give anyone cancer. If that's confusing, don't worry; the stick figures will make it all clear.

Once you've watched that video, consider checking out the others from Risk Bites, including whether BPA is harmful, whether cell phones are frying your brain, and whether or not it's dangerous to eat green potato chips.

What Does "Probably Cause Cancer" Actually Mean? | Risk Bites

Vitals is a new blog from Lifehacker all about health and fitness. Follow us on Twitter here.

Capybaras That Look Like Rafael Nadal

Burly.ThurrFreaking cool. Video is worth it on click through.

Image: © The British Library Board (Royal 12 D xvii)

A one thousand year old Anglo-Saxon remedy for eye infections which originates from a manuscript in the British Library has been found to kill the modern-day superbug MRSA in an unusual research collaboration at The University of Nottingham.

Dr Christina Lee, an Anglo-Saxon expert from the School of English has enlisted the help of microbiologists from University’s Centre for Biomolecular Sciences to recreate a 10th century potion for eye infections from Bald’s Leechbook an Old English leatherbound volume in the British Library, to see if it really works as an antibacterial remedy. The Leechbook is widely thought of as one of the earliest known medical textbooks and contains Anglo-Saxon medical advice and recipes for medicines, salves and treatments.

Early results on the 'potion', tested in vitro at Nottingham and backed up by mouse model tests at a university in the United States, are, in the words of the US collaborator, “astonishing”. The solution has had remarkable effects on Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) which is one of the most antibiotic-resistant bugs costing modern health services billions.

Click here for full story

The University of Nottingham is committed to the principles of the 3Rs of reduction, refinement and replacement. For each project it ensures, as far as is reasonably practicable, that no alternative to the use of animals is possible, that the number of animals used is minimised and that procedures, care routines and husbandry are refined to maximise welfare. The University is a signatory member of the UK Concordat on Openness on Animal Research.

— Ends —

Our academics can now be interviewed for broadcast via our Media Hub, which offers a Globelynx fixed camera and ISDN line facilities at University Park campus. For further information please contact a member of the Communications team on +44 (0)115 951 5798, email mediahub@nottingham.ac.uk or see the Globelynx website for how to register for this service.

For up to the minute media alerts, follow us on Twitter

Notes to editors: The University of Nottingham has 43,000 students and is ‘the nearest Britain has to a truly global university, with campuses in China and Malaysia modelled on a headquarters that is among the most attractive in Britain’ (Times Good University Guide 2014). It is also one of the most popular universities in the UK among graduate employers, in the top 10 for student experience according to the Times Higher Education and winner of ‘Research Project of the Year’ at the THE Awards 2014. It is ranked in the world’s top one per cent of universities by the QS World University Rankings, and 8th in the UK by research power according to REF 2014.

Impact: The Nottingham Campaign, its biggest-ever fundraising campaign, is delivering the University’s vision to change lives, tackle global issues and shape the future. More news…

Burly.ThurrPretty.

Back to collage, Merve Ozaslan

Burly.ThurrAny plans for a Seder this evening?