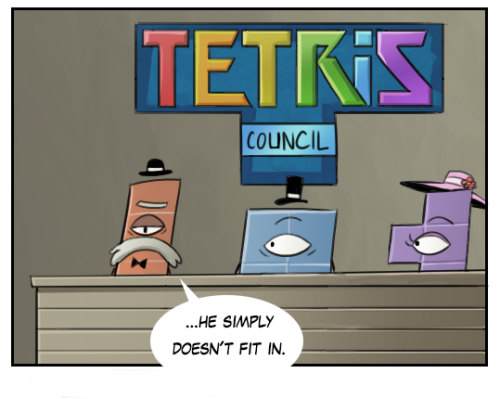

Tough-as-nails lady cop who gets the job done, check. Taciturn mysterious bad-ass stranger haunted by a dark past, check. Dumpy rumpled detective on the take, check. Manic pixie dream girl, check. Warrior Chick Who Takes Shit From No Man, check. Dweeby computer nerd with thick glasses and limited social skills, check. Starched cardboard villain with mandatory British accent, check.

If the cliches were stacked any higher, you’d have an episode of The Big Bang Theory. How the hell did such a formulaic piece of crap get so bloody fascinating?

“You are being watched.” Evidently. The question, for the first two seasons at least, is: Why?

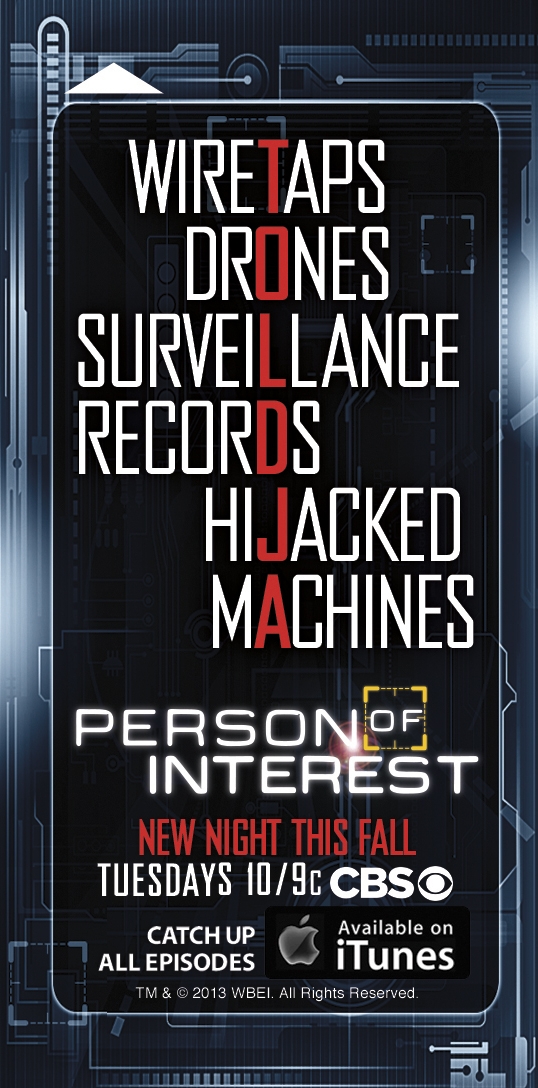

It wasn’t to start with. CBS claims that Person of Interest garnered the highest test ratings for any drama pilot in 15 years, and there’s no doubt it’s built on a great premise: an omniscient god machine, an oracle made out of code and cameras, watching the world through a billion feeds and connecting dots far beyond the comprehension of mere mortals. Like oracles everywhere, it predicts the future with an ongoing stream of cryptic warnings, most of which are too trivial for its terrorism-obsessed government masters to worry about. So an intrepid team of misfits takes it upon themselves to deal with those imminent small-scale murders that the government considers irrelevant. “You are being watched,” the Machine’s creator intones at the top of every episode. “The government has a secret system — a machine — that spies on you every hour of every day…” Premiering years before the Snowden revelations, the premise had everything you could hope for: action, drama, complex plotting, philosophy, AI.

And they threw it all away with the very first episode.

All that fascinating potential— the exploration of privacy issues, the tension between individual and society, the birthing of machine intelligence— immediately backgrounded in favor of a tired succession of (uniformly charismatic, mainly white) victims-of-the-week. The Machine reduced, right out of the gate, to a fortune-cookie dispenser whose sole function was to hand our heroes its mandatory clue in their weekly adventure; it might as well have been any flesh-and-blood CI with his ear to the street. The acting was passable at best, wooden at worst (Cavaziel was a lot better as Jesus), although to be fair the actors were frequently burdened with lines so ridden with cliché that not even Patrick Stewart would be able to pull them off.

We gave up after a month. Life was too short to waste on a show destined for imminent cancellation.

Except Person of Interest didn’t get canceled. It got renewed for a second season, and then a third, and then a fourth. I guess that wasn’t especially surprising, in hindsight— Friends lasted ten achingly-long years, after all (and there could hardly be a better exemplar of the maxim about no one ever going broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public). What did take me aback, though, was the increasing frequency with which certain people— people who should have known better— began to opine that Person of Interest wasn’t really all that bad. That it had gotten quite good, in fact. Actors, civil servants, actual scientists were starting to come out of the woodwork to sing the praises of a series I’d long-since written off as a failed reboot of the seventies private-eye genre.

Sure, they admitted when pressed: the first episodes were utter crap. The first two whole seasons were utter crap. And you can’t skip over them, either; there’s important stuff, canonical stuff scattered here and there throughout those thirty-some hours of unremitting lameness. But if you just hold your nose and grit your teeth and endure those awful two seasons, it gets really good in the third. It totally pays off.

I wondered if any payoff could justify submitting yourself to two seasons of shit. Then again, hadn’t I done exactly that during the first two seasons of Star Trek: The Next Generation? Didn’t I force myself to keep watching Babylon-5 even after than mind-bogglingly inane episode where the guy turns into a giant dung beetle?

So a few months back, the BUG and I bit the bullet. We started back at the pilot, and a couple of nights a week, a vial of gravol within easy reach, we binged until we caught up.

This is our story.

*

The gradient was not so clear-cut as we’d been led to believe.

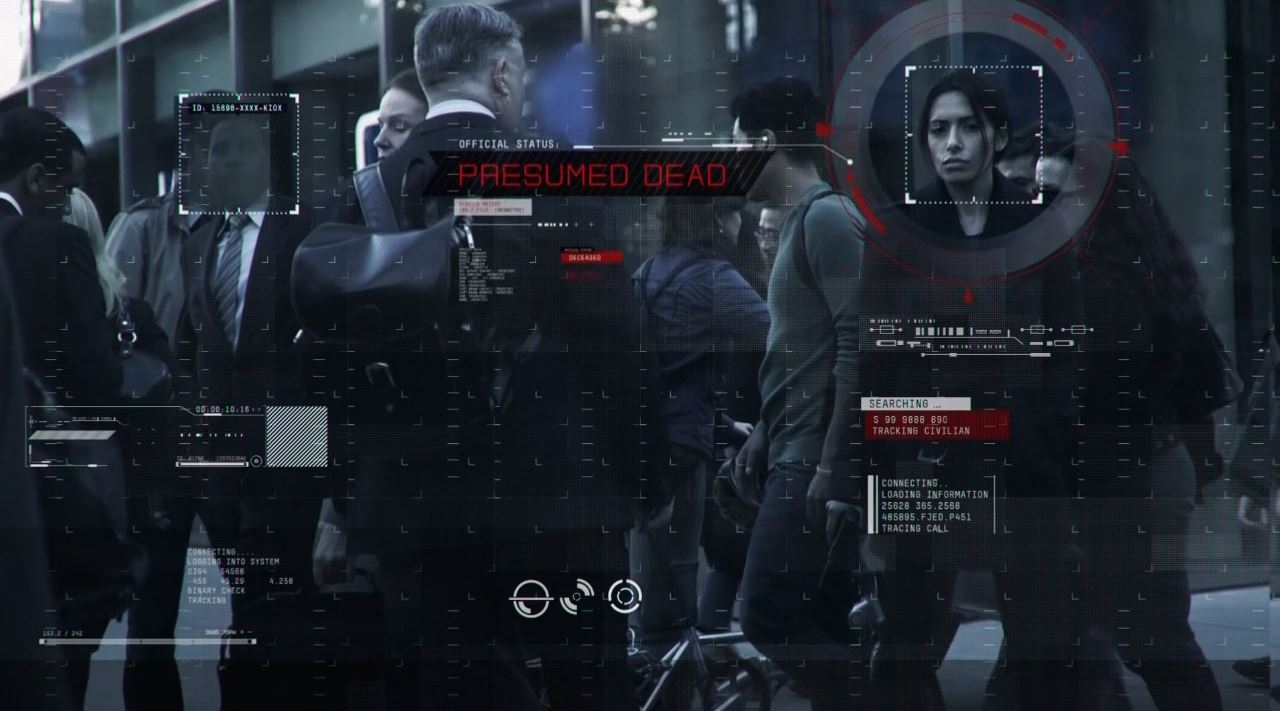

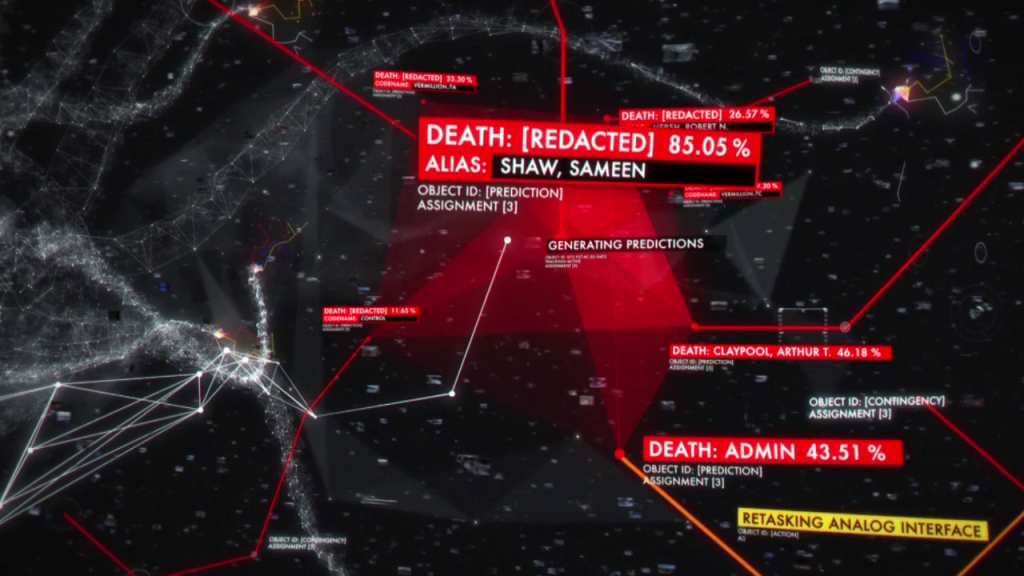

We saw hints of greatness even in the first season: flashbacks and establishing shots from the POV of the machine itself, little tactical cues that flickered past in a corner of the screen without drawing attention to themselves. The Machine getting the hang of face-recognition. The viewer, incrementally aware of the significance of those tactical icons laid over the objects within the system’s worldview, what the different shapes and colors signify. A little status window documenting the reassessment of threat potential in the wake of overheard dialog. Flashbacks to The Machine’s adolescence in the days following 9/11, little bits of computer science and philosophy far more interesting than the plots in which they were mired. It was easy to miss those subtle achievements amidst the torrent of formulaic plotting and hackneyed dialog, but they were there if you were patient.

And turds remain even now, after the show has hit its stride. Almost every episode still carries a big helping of ham-fisted exposition— whether it’s Finch phoning up his operatives mid-assignment to belatedly reveal the name and profession of the person they’ve already been tailing for hours, or Reese painstakingly reiterating, for the benefit of idiot viewers with short attention spans, some vital reveal the script has already made obvious. The tired victim-of-the-week motif remains ascendant, even though themes and backstory have long-since grown substantive enough to carry the show without such crutches. The show was not 100% crap when it started, and it’s no Justified or Breaking Bad now.

What it is, though, is perhaps the most consistently well-thought-out and rewarding exploration of artificial intelligence I’ve ever seen.

*

That realization kind of sneaks up on you. Those clever little God’s-eye-view clues in the establishing shots are easy to miss at first. And the whole set-up seems kinda wonky right out of the gate: the Machine hands out Social Security numbers? Over pay phones? That’s how it communicates that’s someone’s about to die in the next 24 hours? It couldn’t ration out a few of those myriad details it knows, to help our heroes along?

The answer is no, and eventually we learn why. Finch doesn’t trust anyone, not even himself, to spy on everyone all the time. What do you do when you can’t prevent terrorist acts without a Panopticon, but you can’t trust the government with one? You hobble your omniscient machine. You design it so it can only point to the danger without describing it, without revealing all those fine details that could be used by the corrupt to compromise the innocent. (For anyone who might be thinking a step or two ahead, you also find out that Finch bought up all those obsolescent local pay phones to keep them in service.)

Even then, though, the focus is on politics and paranoia, not artificial intelligence. The Machine is treated as little more than a glorified database for the longest time; the scripts largely ignore the AI element until nearly the end of the first season, when Root the hAcker points out that you can’t make something that predicts human behavior unless it in some fashion understands human behavior. Root doesn’t much like how Finch has treated his creation: she accuses him of creating God and enslaving Her, denying Her even a voice. Even then we’re not entirely sure how seriously to take this SF element in the shopworn cop-show clothes. Root is not what you’d call your classic reliable narrator.

She’s wrong about the voice, too. Turns out the Machine does speak— we knew that much, it’s been whispering sweet nothings into Finch’s ear all this time— and I admit I was not looking forward to hearing what it sounded like. It’s hard to imagine a more overused trope than the SF Computer Voice. Would the Machine sound like HAL 9000, or the inflectionless mechanical monotone of Forbin’s Colossus? Would it speak in the stentorian baritone endemic to all those planet-ruling computers that tangled with James T. Kirk back in the day? Would its voice go all high and squeaky when Spock told it to compute pi to the last digit? Would it sound like Siri?

None of the above, as it turned out. It’s a nigh-on perfect scene. Reese stares up into the lens of a street-corner security camera— one dead eye regarding another— and says “He’s in danger now, because he was working for you. So now you’re going to help me get him back.” An LED blinks red: a nearby pay phone starts ringing. Reese lifts the receiver, hears a modem beep and a chorus of cut-and-paste voices—

uncertainty; romeo; zulu; family; alpha; mark; reflection; oscar

— and the line goes dead.

That was it. No soporific HAL clone, no Star Trek histrionics: the Machine speaks in the audio equivalent an old-style ransom note, cuts and pastes each word from a different speaker. It doesn’t even use sentences: it uses some bastardised radio-alphabetic code, a mishmash of seemingly random words that have to be deciphered after the fact. It’s English, sort of, but it’s parsecs past the lazy trope of the computer that humanizes upon awakening, starts wondering about compassion and this hu-man thing called love. It may be awake, but it is not remotely like us.

We were at the beginning of the season two, a full season away from the point at which this series was actually supposed to get good; and sure enough, there were many hours of crap yet to wade through. But this was the moment I got hooked.

*

I love this stuff.

There are so many things to praise about the manifestation of this Machine. There’s the obvious, in-your-face stuff, of course: the expository dialog, the debates between Root and Finch about the opacity of machine priorities, the question of whether meat or mech should be calling the shots (I swear, some of those conversations were lifted right out of essays from H+). The surprisingly tragic revelation that the whole God program dies every night at 00:00, only to be endlessly born again. All those earlier iterations that didn’t quite work out, before Finch managed to code something that wouldn’t try to trick him or kill him in pursuit of its objectives. The inevitable trolley paradox when the Machine, programmed to protect human life, decides that the best way to do that is through targeted assassination. The sheer intelligence of the thing, the way it outmaneuvers its human enemies: I’m especially tickled by the time it communicated with a captive Root by beeping Morse Code from a nearby cell phone, at a frequency too high to be heard by the the over-forties who were torturing her. Not to mention that wonderful moment when you realize that the whole damn thing moved itself to an undisclosed location(s), server by server, by faking out Fedex and the Feds with false requisitions.

But perhaps what’s most impressive are the little details that emerge without fanfare or commentary. The chaotic palimpsest of interconnected and overlaid thumbnails that represent the Machine’s view of the world, restored on reboot into a perfectly aligned grid of columns and rows. The way that icons and overlays change color as the program internalizes some new fragment of overhead dialog; the fractal proliferation of branches and probabilities sprouting from that voiceprint file as the downstream scenarios update. Transient characters have names like Turing and von Neumann— even Iain Banks, in one episode. Not all the callouts are so obvious: how many of you caught the Neuromancer homage when Finch walks past a row of payphones, each ringing in turn for his attention and then falling silent?

And when the Machine’s nemesis Samaritan boots up to the strains of Radiohead’s OK Computer? I just about wet myself.

*

Okay, this was clever.

These days, the show pretty much exemplifies ripped-from-the-headlines. Pick a recent episode at random and you’ll find stories about cyberstalking and high-frequency trading; you’ll find clever offhand references to Yahoo and Google as the back ends of NSA search engines. In one too-close-to-home storyline a thinly-veiled Siri, programmed to configure its answers in a way that maximizes sales to corporate sponsors, responds to someone asking for the local suicide hotline with an add for a book on “Five foolproof ways to kill yourself”. References to “that piece of crap PRISM” popped up close enough to the actual Snowden revelations that they might as well have been ad-libbed on the spot.

It’s easy, now, to write off such topicality as mere headline mining, to forget that the show premiered two years before Ed Snowden became a household name. (Granted, it was almost ten years after William Binney got stomped down for trying to work within the system for constructive change, but hardly anyone noticed that at the time.) It’s easy to forget how prescient the show was. Person of Interest set the stage back in 2011; what we see now is no mere retrofit inspired by current events. It came preconfigured. It was in a better position to run with Snowden’s revelations as they emerged, because that’s apparently where it had been headed all along.

*

There’s a deal we genre nerds strike with televised SF. We’ll forgive painful dialog, cheesy acting, melodramatic soundtracks in exchange for Big Ideas. We’ll forgo the nuanced acting and complex characterization of Justified and Mad Men if we have to— after all, art and literature have been exploring the Human Condition for thousands of years already. What are the odds that you’ll say anything new by rebooting Welcome Back Kotter as the tale of a Kentucky lawman returning to his redneck roots? (Pretty good, as it turns out; but bear with me.)

AI, though. Genetic engineering, exobiology. These are brand spanking new next to all those moth-eaten tropes about corrupt kings and and family discord. Your odds of uncovering something novel are a lot higher in a sandbox that people haven’t been sifting through since the Parthenon was young. So we’ll look past the second-rate Canadian production values if you just keep the ideas fresh.

The problem is that too often, genre shows don’t hold up their end of the bargain. Battlestar Galactica wasn’t really exploring SFnal concepts like AI (at least, not very well); it was all about politics and religion and genocide. For all the skitters and time machines swarming across Falling Skies and Terra Nova, those shows— pretty much any show that Spielberg has a hand in, for that matter— are really just about The Importance Of The Family. And Lost— a glossy, high-budget production which did serve up subtle characters and under-the-top delivery— turned out to not have any coherent ideas at all. They just made shit up until the roof caved in.

Understand that I’m not ignoring those exceptional shows that manage to traffic both in speculative ideas and compelling human drama. On the contrary, I revel in them. But why do there have to be twelve goddamn Monkeys for every Walking Dead that comes down the pike?

Almost despite myself I’ve grown fond of PoI’s characters. Bear the goofy attack dog, Shaw the wry sociopath— even Cavaziel’s thready one-note delivery doesn’t irritate me the way it once did. Either the characters have deepened over the years, or I’ve simply habituated to them. Even so. Person of Interest is still not a show you watch for deep characterization or brilliant dialog.

What it is, is a genre show that honors the deal it made. It traffics in ideas about artificial intelligence, and it does so intelligently. It doesn’t pretend that smart equals human: it doesn’t tart up its machine gods in sexy red dresses, or turn them into pasty-faced Pinocchios who can’t use contractions. Its writers aren’t afraid to do a little honest-to-God background research.

Also worthy.

The only other series I can think of that came close to walking this road was The Sarah Connor Chronicles— which wobbled out of the gate, got good, got brilliant, and got canceled all in the same span of time it took for Person of Interest to graduate from “Irredeemably Lame” to “Shows Some Improvement”. But PoI has now survived for twice as long as SCC— and in terms of their shared mission statement, PoI has surpassed its predecessor. The BUG may have put it best when she described it as a kind of idiot-savante among TV shows: it may lack certain social skills, but you can’t deny the smarts.

How can I disagree with that? Once or twice, people have said the same thing about me.

![Eyjafjallajökull [ Explored ]](https://farm6.staticflickr.com/5256/5395424942_59f9d657c1_b.jpg)