I’m going to tell you a story. At first, it’s going to sound ridiculous. But the longer I talk, the more rational it’s going to appear. (Spoilers for Edge of Tomorrow.)

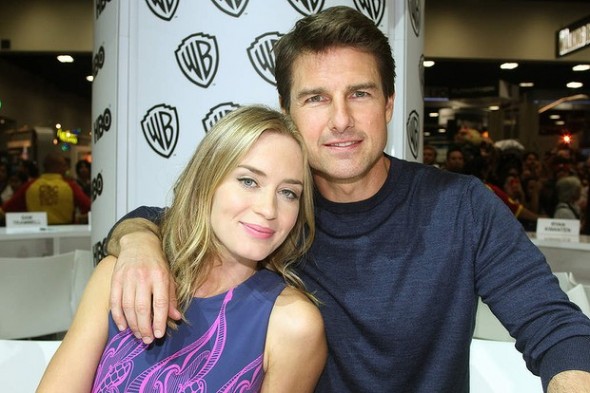

In Edge of Tomorrow, the Earth has been invaded by the alien “Mimics.” Europe has been overrun, and the “United Defense Force” is preparing to launch a massive counter-invasion across the English Channel. At about the half-way point of the movie, the time-looping Major William Cage (played by Tom Cruise) finds himself in a pub in England, listening to some old codgers reminisce about the last time we invaded Normandy. The old men speculate about what it is the Mimics really want. One man says they are on Earth for minerals; the other thinks they’re here for water.

But we don’t really see any evidence of that – in the movie, we get scenic tours of Occupied France and Germany, and all we see are ruins, as far as the eye can see. The Mimics aren’t building mines or settlements, they aren’t even breeding as far as we can tell – they’re all at the front, or laying in wait to ambush infiltrators. It appears that the only thing they are really here for is war. The “Angel of Verdun,” Rita Vrataski (played by Emily Blunt), thinks that the entire goal of the Mimic invasion was to draw Earth’s “top predator” (i.e. humans) into a do-or-die fight, win, and then have the run of the planet.

I think she’s half-right. The Mimics do want Earth to launch a massive counter-attack – but they don’t want to win that do-or-die fight. They want to lose. They’ve got a curse to break.

Edge of Tomorrow is of course strongly associated with the 1993 classic Groundhog Day. Both movies tells the story of an arrogant TV personality, forced into reliving the same day over and over, learning a little bit more each time he wakes up. And the two movies end the same way – with our time-looping hero waking up, finally, to something different. As Phil Connors says, “Anything different is good.”

In Groundhog Day, Phil Connors (Bill Murray) relives February 2nd over and over: no matter what he does, he always wakes up back in his room at a Bed and Breakfast. At the end of the film, Groundhog Day is finally over. Phil wakes up, and it’s tomorrow.

But I always wondered – how would it feel for Phil Connors to go to bed on February 3rd, wondering if February 4 is ever going to come? Even if February 4th comes, what about the 5th? What about Groundhog Day, 1994? I feel like Phil would always be looking over his shoulder, wondering when the next loop is going to find him. But hey - the time loop reset every time he went to sleep, and this time it finally didn’t. He’s probably out for good.

In Edge of Tomorrow, Major Cage finds himself in a time loop that works a little differently – instead of “resetting” every time he goes to sleep, Major Cage “resets” only when he dies. Which poses a question – how would he ever know if he had really broken the loop?

In Tomorrow, Cage’s time looping power is caused by his “hijacking” the time-manipulating power of the alien Mimics. The Mimics are a Hive Mind not entirely unlike the Zerg or the Buggers – the individual Mimics have no personality. A central “Omega” consciousness controls the massive “Alphas,” which control the individual Mimic soldiers. Whenever an “Alpha” dies in battle, the Mimics time-looping power resets the day – they can’t lose, because any timeline in which they do lose eventually gets replaced with one in which they don’t.

On the beach in Normandy, Major Cage accidentally kills one of the alien “Alphas,” covering himself in alien blood. This resets the day, bringing him with it – now time loops every time he dies. Supposedly, this power can be lost – Rita says that if you get wounded, and someone gives you a blood transfusion, it will push the Alpha’s blood out of your veins and you lose the reset power.

But how would she know? Phil Connors knows the loop is over because morning finally comes – neither Rita nor Major Cage would really know that the loop is over until they died and failed to come back. At the end of the movie, Major Cage finds himself in a field hospital, he’s been given a blood transfusion, and he assumes that his power is gone.

But we don’t see any evidence of this. The next time he dies is right after he and Rita manage to finally destroy the “Omega.” They both die in the process – but Cage wakes up again, this time all the way back at the beginning of the movie, with the news that the aliens have been destroyed.

My question is this – doesn’t he still have the time-hijacking power at the end of the movie? Before the blood transfusion, every time he died, he woke back up – and after the blood transfusion, the one time he dies, he still wakes back up. Even if he did lose his power the first time around, he clearly got it back when he killed the Omega and woke back up on the same helicopter where the movie began.

The movie closes with Cage and Rita reuniting – Rita doesn’t recognize Cage, but it’s clear that he’s going to explain what happened, to the only person on Earth who will ever believe him. Roll credits, happily ever after.

But what happens 30, 40 or 50 years later? Cage grows old and eventually dies. And wakes right back up again, ready to start the day. The only way to kill the Mimics is to make sure that they can’t just restart the day where they left off - and the only way to do that is to take their power for good. When Rita and Major Cage lost their power the first time, after a blood transfusion, the Omega was still alive, so the power had a host to revert back to. Now, Major Cage is the last one left standing – so even if he gets a transfusion, it’s possible the power won’t leave him, because it has nowhere left to go.

So let’s spin this scenario out – every time Cage dies, he’s going to wake right back up. No matter how many decades pass, no matter what he does, when he dies, he comes right back to the helicopter, right to the day of humanity’s triumph over the Mimic threat. He’s already been through an “eternity” of resets once – now he realizes that was just the tip of the iceberg, the beginning of a true eternity. He lives his entire life again. And again. And again.

The first time through, he became the world’s most elite soldier. After a few dozen lifetimes more, he’s become the world’s expert in every possible field of inquiry. Maybe he’s not the God, but he’s a God – in the words of Phil Connors, he doesn’t even need to floss. He starts pushing the bounds of science, trying to understand – and maybe control – this power.

But it never works. Cage has already watched Rita, the woman he loves, die in a thousand different ways. And every time, it gets a little bit worse - decades upon decades of memory, lifetimes spent together, wiped away in the blink of an eye.

He gets bored. He gets tired. He gets angry. He realizes the only way to break the loop is to force someone else to break it for him – to kill him and take the power from him. So he tries. Over and over he tries to maneuver the situation so that someone kills him in exactly the right way, under exactly the right circumstances, so that he dies and stays dead.

It’s taking too long. There are too many variables, too many ways for the power to take hold and restart the day before the transfer of power is final. Even if the power is transferred, it might not stick – Rita had it, and apparently lost it. He needs to do something to change the odds – to increase the number of chances. He needs a war. And if the Earth is peaceful in the aftermath of the Mimic war, then he’s going to start that war. He’s the most brilliant man on the planet, known throughout the world as the Friendly Face of the United Defense Force – maneuvering into a position of power isn’t much of a challenge.

But even in a war, he can only be killed once. And that’s when he remembers that conversation in the pub, all those eons ago. The Mimics came all this way, crossed an ocean of stars, just to pick a fight with a bunch of meatbags. Why would they do that? They didn’t come here for minerals or water – they came here for him. They came here because they knew that somewhere, someone was in exactly the right position, at exactly the right time, to take and keep the power.

And apparently, a being that can take and hold the time-reset power is so rare that the only way to find one is to cross a galaxy- it’s not one in a million, or one in a billion, it’s one in a trillion. And the only way to fight a trillion beings is to conquer the galaxy.

This is about more than just his own personal freedom from the endless loop of time – every time he dies, the universe resets. The only way out is through – if he doesn’t find a way to break out, the universe will stagnate, caught forever in a loop. With the United Defense Force in place, conquering Earth takes just a few political and military moves for the Man Who Can’t be Killed. With his knowledge of science and Mimic technology, branching out to the stars can’t be more than a few thousand resets away.

He learns how to transfer his consciousness into multiple bodies, to maximize his exposure into potential enemies – an Alpha is just an extension of the Omega brain, so that the power transfer can happen in more place than one. His armies branch out far and wide, fighting anything and everything with a brain, hoping that someone, somewhere, has what it takes to kill that which can’t be killed. In short, he becomes the Mimics – a single organism, devoted to killing everything, in hopes that maybe, just maybe, there’s something or someone that can kill him first.

He either dies a hero, or lives long enough to become the villain. The “power” to reset time isn’t a power at all – it’s a curse.

The Curse of the Mimics’ Claw originally appeared on Overthinking It, the site subjecting the popular culture to a level of scrutiny it probably doesn't deserve. [Latest Posts | Podcast (iTunes Link)]