Burly.Thurr

Shared posts

Photo

Burly.ThurrSomething went wrong at the zoo again.

Photo

Burly.ThurrVia bunker Jordan.

Karl Ove Knausgaard on the Power of Brevity

Burly.ThurrHaven't read the whole thing yet but so far it's fucking amazing. "To look down is to not face your community—to be alone, to exist outside of society—and, as we see in this story, that is dangerous."

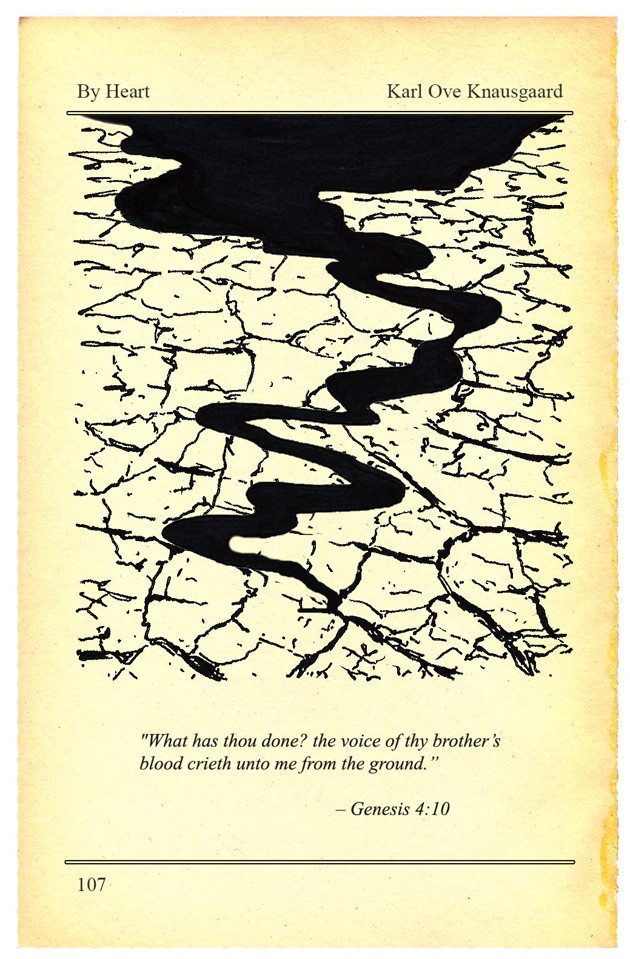

Karl Ove Knausgaard isn’t known for being brief. My Struggle—his celebrated six-volume, 3,600-page autobiographical novel—is an experiment in radical scope, a kind of literary ultra-marathon. How long can a narrator extend a moment?, he seems to ask. How much banality can a story include? How long can a novel digress and still remain compelling?

Related Story

How Writers Can Grow by Pretending to Be Other People

In our conversation for this series, though, Knausgaard chose to examine the biblical story of Cain and Abel—a text he admires for its extreme compression. We discussed the story’s extraordinary economy, its multivalence, and the eternal appeal of family as a subject. (Cain and Abel’s themes—family, ambition, violence, shame—are Knausgaard’s own.) Finally, he gave insight into the process he used to write My Struggle: a willed naivety, a way of writing without thinking, that he compares to improvising music.

My Struggle is being serially translated into English, and the latest volume—Book Four—comes out Tuesday. This installment focuses on 18-year-old Karl Ove’s first job as a schoolteacher in a Norwegian fishing town. Living alone for the first time, he makes his first stumbling forays into work, writing, self-determination, and sex. It’s a story told with a comic grimace—the mature narrator bears unblinking witness as a young man’s overblown ambitions are cut down, one humiliation at a time.

Knausgaard’s work has been translated into more than 15 languages. In addition to the widely-praised My Struggle series, he is the author of Out of This World and A Time For Everything. He lives in Sweden and spoke to me by phone.

Karl Ove Knausgaard: I first heard the Cain and Abel story at school, when I was seven or eight. My teacher told it to our class, and it very much made an impression on me. I returned to it later when I was writing a novel which is set in the Bible, so to speak, and I re-read all those stories again. I was struck by how extremely small it was, just 12 lines or something. It was almost shocking to see that this little story could have such an impact, and become the big story about killing, violence, jealousy, brothers—so many huge topics within the culture.

I need 300 or 400 pages to say something significant. I need space to express simple, banal truths—I don’t have the ability to express them without that space, and a novel for me is the way of building that space. But Cain and Abel always surprises me in the way it manages to be both extremely powerful and extremely short.

In some ways, this concision is typical of the Old Testament. If you look at other very important texts—say, The Odyssey—it’s often different. The Odyssey is very loose and very long, and it’s a completely different way of storytelling. You have that looser, longer form in the Bible, too, but not in this story. In the Bible, if it’s very important, it’s very short. If it’s not important, it’s very long. That’s a rule in almost all texts.

I was invited to be a consultant for the New Norwegian Bible translation of this story. They made lots of different bibles available to us—the King James, of course, but also Swedish bibles, Danish bibles, old Norwegian bibles. The fun and most interesting thing for me was that we had a bible-translation computer program that made all these different editions available. We could click on a single word and get a translation of it. This helped me get closer to the Hebraic original, which was extremely useful during the work with the text.

The Hebrew text is very raw and very direct—almost impossible to translate. I tried to keep as much of that intact. That version has tremendous power because it’s so simple, with the same words coming over and over again in this short passage: earth, blood, faith. The language is so archaic and interesting. Though I haven’t shown this to anyone who’s mastered the language, so I may get everything wrong, this is my sense of the Hebrew original, when Cain has seen his sacrifice rejected by God:

It burned in Cain and his face fell.

Jehovah said to Cain: “Why do you burn, and why does your face fall?”

The simplicity, and the complexity in the simplicity: It’s bottomless. These are texts people have written about for thousands of years, and keep having different kinds of understandings about. The text is so rich and complex that you can take out one element and look at it, and find it expresses something deeply true. It can support all kinds of different interpretations depending on the way you live, or when you live, or who you are.

For instance, I became very interested in the way looking is described in the text. Jehovah looks down at Abel instead of Cain, and that’s when the jealousy begins. As a result, Cain’s face falls—another way of looking down. Jehovah then tells him, “Look up, because if you don’t look up evil will creep at your door.” I interpret this as being about the obligation of looking up at others, of facing the other. To look down is to not face your community—to be alone, to exist outside of society—and, as we see in this story, that is dangerous. I wrote about this when I wrote about the killing in Olso and Utoya three years ago. He [the mass-murderer Anders Behring Breivik] looked down. And if he planned this massacre with someone else, it would have stopped him. It would have been impossible. He could only do it because he was alone.

All those kinds of relevancies exist in this text. You may say that you reduce it when you use it as a psycho-sociological thing, but I don’t see it like that. I see it as the opposite. You can take one element out and look at it, and let it express something deeply true—without diminishing other potential interpretations, or the text’s overall richness and complexity.

I need 300 or 400 pages to say something significant. I need space to express simple, banal truths.This piece could also be about a basic moment in human history: the first murder, and its connection with sacrifice. The story shows us that sacrifice is meant to take the place of violence. The sacrifice Jehovah wants to see is the sacrifice of Abel’s sheep, which is blood—not the vegetables Cain grew. The next thing you know, Cain’s killed his brother—which is not just blood, but his own blood, spilled on the earth. This brings us in a direct circle back to the sacrifice. When he wrote about this story, the French philosopher Rene Girard wrote that sacrifice—symbolic violence—is an act meant to replace transgression against life. It unites us as a “we.” Without it, there is no “we”—and Cain turns against Abel, brother turns against brother. Symbolic blood becomes real blood. Inside a society, that’s a very dangerous thing.

Of course, it’s a story about family, too. And though I don’t reflect on themes when I’m writing, it’s obvious to me that I’ve always been writing about family. I think it’s because I’m interested in identity—and the family is the first group of people who form your identity and sense of self.

When my last daughter was born, I saw what happened when she was lifted up in the first seconds of her life. She was just by herself. She hadn’t met anyone. But she was lifted, held onto by the neck, and looked at by my wife, and by myself. Those kinds of bonds are the first you have, and you’ll always define yourself in relation to those few people. Later, you’ve got your larger community. You’ve got your nation, and your profession. But it’s all layered on top of this core. The core is the same, no matter what.

I wrote my own version of the Cain and Abel story because I wanted to write about brothers. There’s a lot of me and my brother in that retelling of the story. I’ve always been interested in writing about all those mixed feelings brothers have: your jealousy, and hatred, but always a kind of unremitting love. My brother could do anything he wants—but no matter what kind of horrible thing he does, he would still be my brother. And I think it’s the same way with him.

Part of it is because it’s always been us against our parents—the bond there of coming from the same place, but still being very, very different. When so many qualities are the same, but so much is different, it allows for the kind of compression you see in the Cain and Abel story. It’s a very good place to write from. It’s also a story about losing complete control. Because losing control is the worst thing you can do, and no one wants to do it—I’m sure about that. What is it to lose control so completely?

In a completely different sense, writing My Struggle has been an exercise in giving up control. Every morning now, I write one page. I get up early and write one page in two hours. I start with a word. It could be “apple” or “sun” or “tooth,” anything—it doesn’t matter. It’s just a starting point—a word, an association—and the restriction that I write about that. It can’t be about anything else. Then I just start, without knowing what it’s going to be about. And it’s like the text produces itself.

I’m not talking about quality. For God’s sake, no. It’s not like this text ever looks good or anything. It’s just sitting there writing. Not thinking, and writing. I think it’s a state of mind, one I usually compare with music. When you watch musicians, they’re not thinking about what they’re doing, they’re just playing. Well, the same thing can be with writing. It’s just writing.

When you are not aware of yourself, you start to write things you have never thought about before. Your thoughts do not take the path they would normally have followed, and the thinking is different from your own. The language is in you, but it’s out of you, and it doesn’t belong to you. That’s what literature can do—when you throw something in, something else comes back.

This approach was something I discovered very early on, when I first started to write with ambition. I was 17, 18. I just wrote. I didn’t think. It wasn’t hard, because I was so naive and innocent. But what I mostly did was spit out clichés.

Later, I had many years when I couldn’t write because I felt I knew too much—suddenly, I had a notion of quality. But when I was 27 or 28, I had a new experience for the first time: I just disappeared somewhere. I just wrote and followed the text. It was like reading, basically. I knew I was onto something because I couldn’t predict what was coming and I couldn’t identify it with myself when I read it—it was outside my normal reach, in a way. Not that it was better. But it was different.

This is what makes my work so difficult for me to read and see again. The first thing I think is—oh Jesus, it’s naïve. But in that naivety there is something that’s very direct and true, in a sense.

There’s a difference between writing naively now and when I was 20. When you’ve been writing for 20 years, you know something about writing. You don’t have that knowledge present as you work, but it is still there somewhere and kind of directs you.

Now I have to learn to write differently. I can’t repeat what I did in My Struggle.For My Struggle, the revision process developed during the process of writing those six novels. I edited the first novel with my editor—we did it like a classical novel, more or less. It wasn’t hard. There were some bridges made, and then it looked like a novel. But the second book we hardly edited at all. Much of the editing I’m doing while I’m writing, so when I reached the end—we just kept it, basically. We took out some pages, of course, but it was mostly there. The other books were written in a similar way, with the exception of Book Six—that was so long we needed to take out 150 pages. The others are more or less left alone.

But now I have to learn to write differently. I can’t repeat what I did in My Struggle. It’s become a kind of technique: I write a little bit about how I feel about something, a little bit about failure or shame for something, and then there is a reflection of a more essayistic kind, and then there is a description of something ordinary, and so on. I can’t write that way for the rest of my life. I would be less and less satisfying for myself because there’s nothing new in it. Or, the subjects can be new, but the insights are exactly the same.

What I’d really like to do is think differently, but that’s impossible.

Starting to write differently will be very difficult. Maybe it will create a kind a vacuum where it will be impossible to write. That has happened before. It will happen again. And it will pass again.

The privilege of a novelist is that you’re able to sit for three years by yourself, and no one’s interfering with anything if you don’t want them to. If you have faith in your writing, it’s easy. It’s when you remove that faith that things become difficult—when you start to think, this is stupid, this is idiotic, this is worthless, and so on. That’s the real fight: to overcome those kinds of thoughts. When you start a novel—well, 99 out of 100 novels start in a stupid way, I’m sure. You need to go on so that it can become something. Maybe it will take 50 pages, or 100 pages, but it will be okay.

When I go to bed, I look forward to the next morning because I know I have these two hours to write. It’s a magical place. And I know it’s going to happen. I can trust it.

Quick change of mind on social issues

Burly.Thurrvia David Pelaez. I like the inevitability that this chart implies. Even if it takes nearly 200 years like in the case of Interracial marriage.

As Supreme Court hearings for same-sex marriage start today, Alex Tribou and Keith Collins for Bloomberg look back at timelines for past social issues, such as interracial marriage and abortion.

Each line represents an issue, and the height shows the number of states that removed the ban each year, so you end up with lines that increase slowly, and then there's a sudden jolt upwards that ends in federal action. Note the quick increase over just a few years with same-sex marriage. Marijuana legalization on the far bottom right is getting started.

Scroll down the page for more details on each issue, with moving lines that provide a sense of change and the now familiar gridded state maps filled over time.

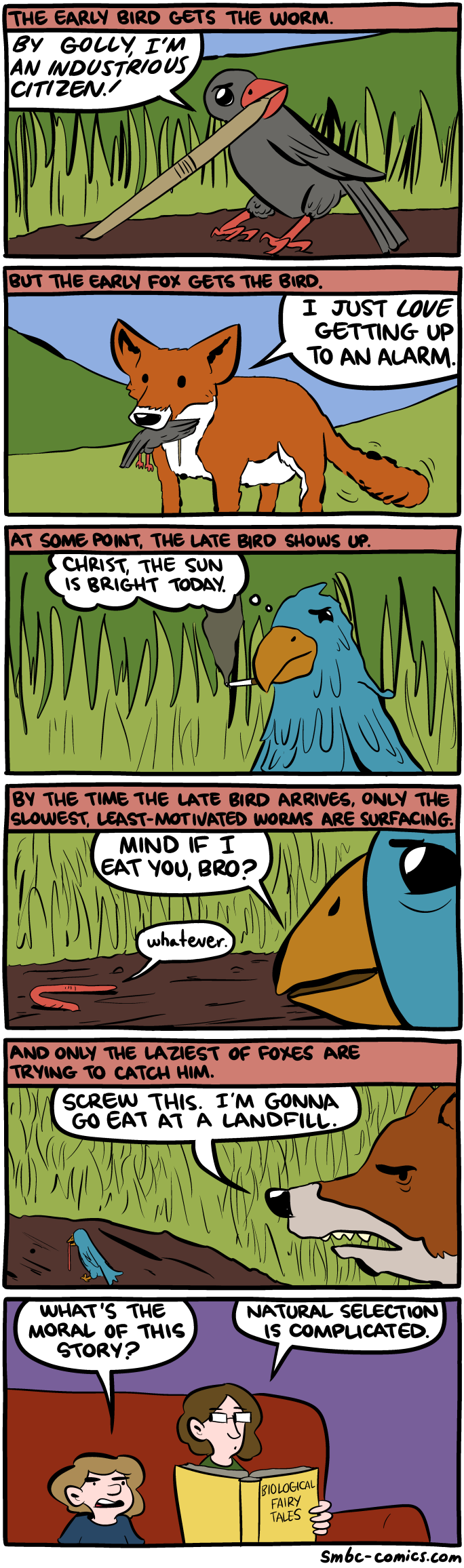

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - On the Topic of Early Birds and Worms

Burly.Thurrvia sophia.

chasibunny: phantomsolari: Obama takin it to a WHOL NUTHA...

Burly.ThurrI mean, there have been some excellent highlights, but thinking I might have to make some time to watch the whole thing.

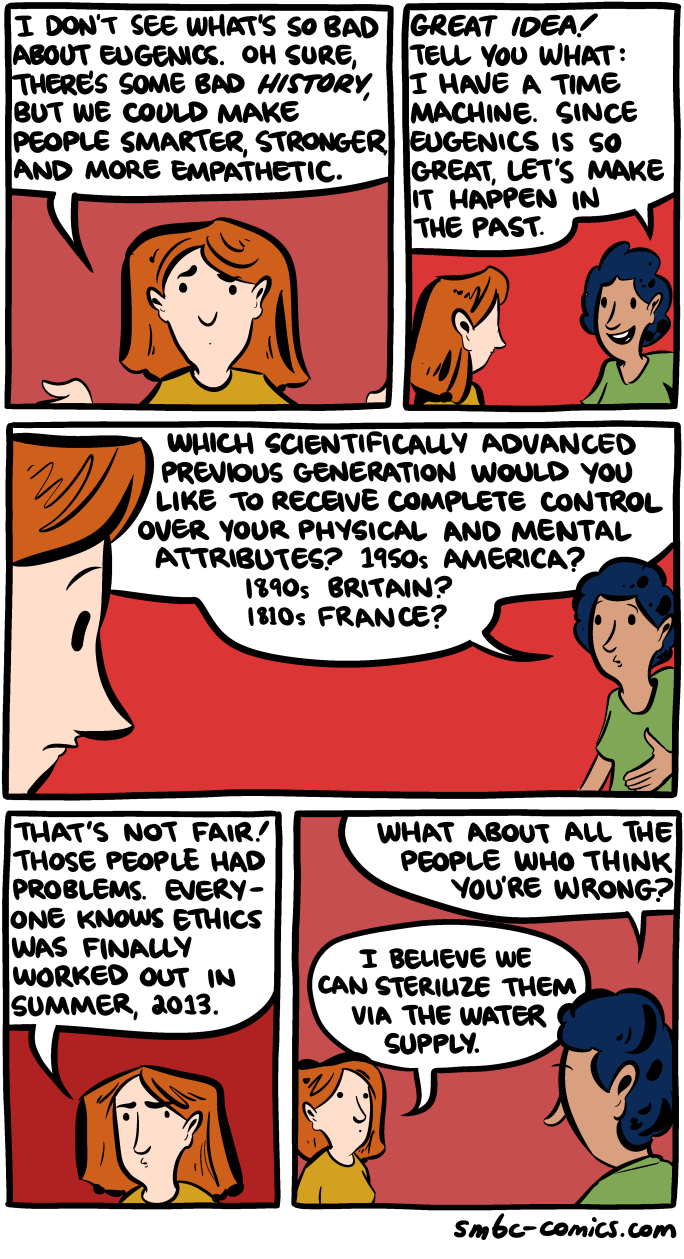

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Eugenics is a great idea!

Burly.ThurrSo well put.

Job Security

Burly.ThurrFinally a purpose for a philosophy degree!

Volkswagen chairman Ferdinand Piech quits in power struggle

Burly.ThurrI wonder why Germany still has such success with trade unions: "The message was clear: whoever wants change at a substantial German company needs to consult the trade unions first." Quoted from the article I'm actually trying to share: http://theconversation.com/vorsprung-durch-realpolitik-what-vw-power-games-say-about-german-ceo-culture-40396

Looks like Bugatti Veyron Super Sport colors.

From the article:

While there's no official confirmation on this, you are looking at Ferdinand Piech's personal Porsche 918 Spyder. Sure, one would expect somebody in his position - he also owns ten percent of Porsche, to own an example of Zuffenhausen's untimate machine.

4 pictures and full article

.

sandandglass: Top ten Obama jokes from the 2015 WHCD (full...

Burly.ThurrVia David Pelaez.

sandandglass: Video: Cecily Strong at the 2015 White House...

note0157h7: I did some of these (a few of which were retweeted)...

Burly.ThurrShared for the comment.

I did some of these (a few of which were retweeted) and got a bunch of ‘gater pouting - they were clearly camping the tag just so they could piss and moan at people who don’t appear in their G A M E R G A T E tag searches. One of them took the opportunity to start spouting his conspiracy theories about how Aaron Diaz is a stalker.

Thanks for the validation, you shit-magicians.

Comedian Maria Bamford discusses suicide, OCD, and buying elephant costumes for her dog on Etsy

Burly.ThurrMaria grew up in Duluth!

It’s almost a shame to confine Maria Bamford to text. After all, the 44-year-old comedian's shape-shifting voice has defined her standup career. Bamford has an uncanny ability to convey an entire character with the subtlest tonal shift. When her voice is just a little huskier than normal, she’s a smarmy Hollywood ladder-climber. A little higher and with a slight quiver to it, and she’s that overeager coworker who’s just dying to go to Quiznos for lunch. And Bamford uses that voice to deliver a one-of-a-kind set about OCD, suicide, organized religion, and her pet pugs.

I spoke with her earlier this month about how she writes jokes, how she makes the saddest parts of the human experience funny, and finding dog clothes on Etsy.

Danielle Kurtzleben: A lot of your jokes seem to be about being an outsider — having mental illness, being an unconventional comedian, being single. What is it about being an outsider that you find so compelling?

Maria Bamford: It’s all perception, thinking that one is an outsider. I mean, the thing I like about standup is that it is independent. And nobody can tell you that you’re not doing it right. I mean, they can, but you can still keep doing it.

And you get to say exactly — exactly — what you want to say, and do exactly what you find funny.

So it’s a delightful art form. My friend Amy just gave me a good premise for a joke today. We were talking about how friends are always in flux and, at least in LA, it’s like marketing, like you’ve got to stay on somebody’s email list and tweet at them, like signing up for some sort of service: "Are you still interested in our, uh ... ok! All right! It sounds like you're busy!"

In a big city, it becomes sort of service-oriented: "Are you within my driving range? Oh, we actually don't work. You seem like a really interesting person and, you know, I want to support you, but I know geographically I can’t."

DK: Is that where your jokes materialize? From conversations with friends?

MB: It’s a mix of stuff. I have a joke right now. It’s about my friend Amy, but really, it’s like all the voices are me, you know? Or versions of me. May I tell it to you? The joke?

DK: Absolutely!

MB: It’s happening. It’s too late now. You can’t stop it. It’s already hit the gate.

My friend Amy is always trying to get me to do stuff: [quivering, excited voice] "You want to go horseback riding?"

[normal voice] Oh god. What is it?

"You’ve got a horse and a dusty trail, with two lesbians who used to be a couple but now they run a small business together, and you have to wash the horses with a chemical that’s blue with no label, and you cut up carrots and you put them in a bucket, and the horses bite."

Okay. I’ll go once. But I’m going to cry all the way there, and I’m going to need a Peanut Buster Parfait on the way back. [manic] Ice cream. Hot fudge. Peanuts. Ice cream. Hot fudge. Peanuts. Ice cream. Whipped cream! Topped with cherry!

The thing is, I’m the one who tried to get a friend to go horseback riding. And it’s hilarious, because now she’s totally into horseback riding and I don’t want to go.

But that’s how I feel about doing things. The next thing is she said, "Maria, do you want to go swing dancing?"

People are still doing that? The war is over! There’s plenty of pantyhose for everyone!

"It’s on Sunday from 2 to 4, just when you don’t want to do anything, and even if you bring a partner you’ve got to dance with strangers the whole time, and some of them are drunk, or from the era where women weren’t allowed to talk back, and—"

I’ll go for three years. I’ll go for three years. And I’ll do my hair that way. And I’ll do the lipstick and I’ll get the shoes, but that is IT.

And the thing is, I’m the one who tried to get friends to do it. So it’s me. But — what was the last one?

"Do you want to go to a fitness boot camp?" — and this is one that my friend did actually try to get me to go to.

Oh god.

"It’s every day at 6 am, but you’ve got to be committed. They’re trying to get you into a shape. And you get to hold a basketball, but you don’t actually play basketball. And you put on boxing gloves, but you never get to actually box, and you run and you run and you run, and there’s no game element to distract you from the fact that you're running and running and running"

Here’s what I’m going to do: I’m going to go every day for 14 days in a row. And I'm going to get excited about it. I'm gonna tell people about it. And I’m going to get other people to go. And then on Day 15, Tonya — and I know it’s going to be Tonya — is going to say, [peppy, cheerleader-ish voice] "Okay, Maria! Today I want to see you push it!" And I’m never going to go again.

"But will you forget to cancel the automatic debit from your checking account for the next two years?"

[whispers] Of course I will. I love you so much.

My friend did get me to go to a fitness boot camp, and it was so miserable. There was no fun to be had! And we tried to make it fun, we tried to have some laughs, but then they wouldn’t let us laugh during it because we were distracting.

Listen to Maria tell her new joke, complete with her trademark voices and a journalist cackling in the background.

DK: Did you at least feel like you were in better shape?

MB: Oh yeah, totally. We got into great shape, but who cares? It was just so miserable. At least let’s, like, have weird races. Let's race each other and have prizes. I mean, if we’re going to get all serious about it, let’s do the Hunger Games. Let’s get really weird. If I could have won something or if there was something like, "Fall upon the rabbit!" and we all have to chase this rabbit. "Fall upon it! With your knives!" It’s violent, but it’s great cardio.

DK: Who are some of the best comedians you are seeing out there right now?

MB: There are so many wonderful comedians. Kate Berlant — she’s out of LA, and she is a delight. And then I just saw a few comics from Chicago that were just spectacular. Rebecca O’Neal was just great, and then Katie McVay I also saw out of Chicago, and she was really wonderful and super-funny.

I just think it’s a real renaissance — there are so many great comics, not only people older and the same age as me, but people who are only 12. Just nubile 12-year-olds.

DK: What do you mean by "comedy renaissance"?

MB: I think it's a boom. There are just so many more comics, which also means great comedians, and it’s really wonderful. I just remember when I started out, there just weren’t as many open mics or venues. I don't remember comedy being revered that much — and now it seems to be seen as an art form.

It used to be listed next to karaoke at the end of whatever the free paper was. And maybe it should be. Karaoke is an art form. It’s quite beautiful.

DK: You do a great job of making some potentially depressing things, like suicide or OCD or loneliness, really funny. How do you navigate that line?

MB: I think it depends on the audience. The people I do it for are already on board. I think I could do that material in a different venue or with people who didn’t know what they’re coming to see, and they would be pissed and bummed out. I think a lot of it rests on the audience. It’s not that I’m a genius. It’s that the people that are coming are ready to hear it. They think it’s in the zeitgeist. Like, I’ve felt like there's been so much more support and openness about mental illness — Catherine Zeta-Jones on the cover of People saying she’s bipolar. It’s just really wonderful. But yeah, I’m definitely preaching to the choir.

DK: Maybe that’s what’s going on in comedy, the same thing that’s going on in music — you can go on Spotify and find really niche things. You can find someone who plays calliope music, if you’re into it.

MB: Which is so great! It’s made it possible for artists of all kinds to have — all sorts of craft people have careers and have incomes. Like how I shop only on Etsy, for the most part, for gifts and stuff. And that’s all people like me who are, you know, making a specialized thing, and somebody’s going to look for, "I need an elephant costume for a pug, but somehow I want it to be knit." Well, I’m going to search for that on Etsy.

DK: Is that something you’ve searched for?

MB: Oh yeah. I have an elephant costume for my pug.

It’s so great. I don’t think I would have been able to have a career before the internet.

But then, if you don’t ever see whatever else is out there, you don’t know. There are huge swaths of comedy that are not represented by hipster comedy coverage. Like in my neighborhood, there’s a giant Armenian comedy show that’s put on in this theater in Glendale. That is not discussed in the LA Weekly, but if you seek it out you can find it.

So is that good, that you can find exactly what you want? Or is it making it so that everyone’s more segregated into different things?

I don’t know. It’s hard to say, because before, it was you just get whatever you got. I love Steve Martin, but a lot of people had Steve Martin albums, and I didn’t find out about the Mexican comedian Cantinflas until I moved to LA.

DK: I’ve read quotes from comics like Chris Rock about fears of trying out new material on some audiences — the fear of an audience being too easily offended. Do you ever feel that?

I don’t know. I think it’s just like it’s always been. It’s a public forum, and maybe there's more social media, but things pass over so quickly. I mean, people have like 48 hours of "Oh my god, can you believe they said that? Oh, Christ." And then it’s on to the next new crisis. People are fairly forgiving, or they worry about other things.

Of course, I've had things that have been negative happen on the internet, where I’ve felt scared, and it’s like, so what? It’s okay!

It’s like we’re at a giant potluck dinner and someone is yelling out, "I hate you! You brought the wrong dish! You said you were going to bring a casserole and you brought this thing, and I think you’re a f**king idiot! And you're evil and you should have never been born!"

"...Oh, okay."

It’s just a group of people talking to each other. So the only people who are paying attention are other human beings.

I think everybody’s doing the best they can, and sometimes it’s not that great. I don’t know. Life is hard.

I’ve had some things where my manager called me: "Oh, this thing happened, and you really need to redress it, because somebody said this on the thing." and I’m like "Ehhhh … maybe not."

DK: And it never ends up blowing up?

MB: And if it did, it’s okay. The worst that can happen is the worst thing that can happen.

The worst that can happen is that someone finds out I’m not always the nicest person. Let’s say I was grumpy on an airline flight or something. Well, that’s for sure happened. Then what’s the worst that could happen? I could be jailed. Mmm, probably not, but if I were, I’d be jailed. And no one would ever talk to me again. Well, I like to read. And sometimes in women’s prisons, they have dog training camps.

I’m not saying that that would happen, and maybe that’s thinking too big, but even if all is lost, people are dealing with a lot more than that. So it’ll be fine.

Fuck Belle Gibson And The Enablers She Rode In On

Burly.Thurr#magicalthinking beat

“Wellness Guru” Belle Gibson lied about having terminal brain cancer and made a killing peddling bogus cures. At Boing Boing, Xeni Jardin excoriates Gibson and “the culture of magical thinking and hero idolization that built her myth into a profitable business, ignoring decades of real science, and placing vulnerable people with cancer at real risk of death.”

Calvin and Hobbes

Burly.ThurrI'm pretty sure this is an Irish blessing.

Goodbye, cruller world: the first doughnut in space is surprisingly tragic

Burly.ThurrIt almost fell directly through a contrail, highlight the very-low-but-not-zero risk of a space food strike with an airplane (like a bird strike, but higher in the atmosphere).

On April 9, 2015, a couple of Swedes made history by sending a doughnut into space.

The video shows how they attached both a camera and a doughnut to a weather balloon, and then sent the balloon 20 miles up (32 kilometers). That took the doughnut beyond the stratosphere — though, technically, this isn't considered outer space, which starts 62 miles (100 km) above Earth. The balloon later landed in the water, where the pastry was recovered by the Swedish Sea Rescue Society and returned it to the group.

The beautiful journey shows the blue magnificence of Earth's oceans, the haze of light playing upon the atmosphere's edge, and the incredible endurance of the doughnut's colorful sprinkles. Yet somehow, it's bittersweet. Though the video shows the beauty of both the doughnut and this blue marble we call home, it also serves as a poignant farewell from pastry to planet.

But then it fell back to Earth, so the Swedes ate it:

Putting novel foods into space — and recording these historic achievements — has become an odd fixation of people with weather balloons and GoPro cameras. Natural Light made a video of beer in space, Andy Shovel sent a burger and chips to space, and some Harvard students floated up a hamburger.

So why balloons? In part because it's extremely difficult to get these foods into space via regular spaceship. As Mary Roach described in Packing for Mars, conventional foods aren't very well-suited to space travel. On March 23, 1965, a corned beef sandwich was brought aboard the Gemini III capsule. But before astronaut Jim Young could eat it, he had to stash it — the sandwich broke apart too easily and risked spreading crumbs around the ship (which in low gravity are almost impossible to extract).

Since then, astronauts have been limited in what treats they can take to space. NASA says that thanks to vacuum-sealed packaging, astronauts can now bring brownies aboard the International Space Station. Someday, a doughnut may leave Spaceship Earth again.

Maybe next time, it won't be a tragedy.

WATCH: 'A time lapse of Earth from the International Space Station'

The real side effect of a gluten-free diet: scientific illiteracy

Burly.Thurr"Facts are great, but if you don’t acknowledge the power of the narrative you have to throw up your hands in frustration."

Walk into any grocery store or coffee shop and you'll find gluten-free muffins, gluten-free chips, and gluten-free bread. Gluten has replaced fat as the ingredient we love to shun.

The Gluten Lie by A. J. Levinovitz

And yet, scientists can't find any good evidence to support this fad. Gluten is a protein composite that gives shape to grains like wheat, rye, and barley. And it's true that a very small fraction of people have celiac disease, a real medical condition that causes their bodies to violently reject gluten. But that's only a small fraction of people, and it's not enough to explain the craze. The rest of us are going gluten-free without any real scientific basis for doing so.

It's exactly because the gluten-free diet has surged in popularity recently, despite the science, that Alan Jay Levinovitz, a professor of philosophy and religion at James Madison University, became fascinated by it. I talked to him about his new book, The Gluten Lie, to better understand why we've gone against this grain to the tune of more than $10 billion this year.

Julia Belluz: You are an academic specializing in Chinese philosophy and religion. Why did you end up looking at diet?

Alan Jay Levinovitz: The most famous myth in the world is the dietary fall from grace. Adam and Eve go into the garden, eat the wrong food, and become mortal. So it makes sense to us intuitively that everything that’s wrong with us can be traced to a mistake we make with that we eat.

These myths are based on really powerful narratives, stories about how we construct our identities. So throwing facts at a narrative of paradise past isn’t going to do anything. It’s not established on facts to begin with. You have to deconstruct the narrative. Facts are great, but if you don’t acknowledge the power of the narrative you have to throw up your hands in frustration.

JB: How did the gluten-free narrative become the dominant one in diet now?

AJL: There was already the popularity of low-carb diets for people who want to lose weight. The arguments against gluten hooked up with the fear of carbs. [It also connects to] this myth that there was a healthier time in the past, different from modernity, when we didn’t have gluten in our diets. People saw gluten as part of a modern engineered agriculture that took us away from a paradise past associated with Paleolithic man and natural eating habits.

One of the things you need for a good diet narrative is to suggest that foods you must avoid are not just high in calories but are wrong, bad. Gluten fit that narrative well.

JB: But was there a tipping point? Because it seemed like overnight, gluten-free products were in stores everywhere.

AJL: It was slow and steady progress. [Alternative medicine proponent] Joe Mercola started talking about evils of gluten pretty early on. Jenny McCarthy started talking about it in the early 2000s. The book Dangerous Grains came out in 2002. This was a solid 12 years before Wheat Belly and Grain Brain [two popular books that promoted the gluten-free way].

The success of Wheat Belly really played up this narrative of a fallen present — that we now have [genetically modified] "Frankenwheat." William Davis [the author of Wheat Belly] is a master of the idea that there are all these engineered foods making us sick. That book appealed to these timeless myths and won over the general public.

These themes recur again and again. They are appealing to the same myth: there are a lot of mysterious [health] conditions we don’t understand, and it must be that there’s something wrong with our conventional diet. They come up with this idea of a past before agriculture where everyone was happy because they avoided eating grains.

Bread is now seen as a dietary enemy. (Universal Images Group.)

JB: What’s the potential fallout from our obsession with gluten-free?

AJL: The biggest danger is that the kinds of rationales that people like William Davis [author of Wheat Belly] and David Perlmutter [author of The Grain Brain] contribute to scientific illiteracy.

If you read Davis or Perlmutter and go gluten-free and feel better, it makes you believe the way these men think is right. Going gluten-free might make you feel better, but [it could be] because you’re more careful about what you eat or because you're cooking at home more. In the same way, if you watch Dr. Oz and feel empowered, you think Oz actually represents science. That is a real danger because it’s not true.

JB: So what do real scientists say about the health benefits of a gluten-free diet?

AJK: The real scientists, people who are actually researching this stuff, happily admit that right now we just don't know. The state of science right now, as best we know is this: the vast majority of people who think they react to gluten don’t. That much we can be sure of. There may be a small segment of the population sensitive to gluten and who don’t have celiac disease, and only time will tell if that really is something. That’s where we are right now.

Homeless Millennials Are Transforming Hobo Culture

Burly.Thurrvia bernot. Seems to run counter to the decline of hobo culture previously shared in this stream.

Culture

The vagabond ecosystem is changing thanks to cellphones, Wi-Fi, Craigslist and Google Maps. Michael Portugal

On Reddit, he’s /u/huckstah, an administrator on /r/vagabond, a subreddit with nearly 10,000 members—many of them identify as “homeless”—who trade skills and stories. On “the road and the rails,” he’s Huck, and even after we speak twice by cellphone, he tells me he’d prefer I don’t print his real name. “People say, ‘Well, you chose to become homeless.’ But that’s wrong,” he says. Huck says he’s been a hobo for upward of 11 years and started hopping trains and hitching rides at 18. “I did not choose to become homeless. If you want to say I chose to become homeless and sleep on the streets, really all I have to say is fuck you. You’ve never experienced it.”

Or maybe you have experienced it, thanks to the recent Great Recession that caused a spike in homelessness—especially for families—with its tidal wave of foreclosures. And if you have, there’s a good chance you were probably one of the many homeless with a mobile device, a sight that has become increasingly common. The ubiquity of cheap phones and even cheaper data has prompted even longtime homeless to join the growing ranks of people with a cell connection but no house. “The day I started on the road, I had a flip phone, an iPod, a TomTom GPS, an atlas, a laptop, and free Wi-Fi wasn't very easy to find,” says a medic who’s been a hobo for four years and asks me to identify him as “Nuke.” (“I have a pretty decent amount of training and experience in treating combat trauma.”) He now lives out of a ’91 Ford pickup and says, “I have a smartphone, a laptop, and free Wi-Fi is everywhere.”

The rise of the mobile Internet has made a hobo’s life easier, Nuke says. But when I ask Huck about how he and fellow travelers use their smartphones, I get the sense that even for the digitally connected homeless, life is far from easy. “I keep my phone off a lot, or in airplane mode,” he says, “because we can only charge up for a short time—maybe once a day, or sometimes it will be two to three days between charges, maybe an hour of charge.” For Huck and his fellow itinerants, smartphone usage is measured in instants. “We check Google Maps and then we turn it off, or we make a quick phone call and then we turn it off.”

Try Newsweek for only $1.25 per week

That’s a pity because a smartphone can be even more useful for a homeless person than it is for those with a regular roof over their heads. Case in point: Smartphones provide on-the-go weather forecasts, convenient for an everyday life but essential for a homeless one. “You have to keep an eye on the weather when you're living outside,” says Mike Quain, a 22-year-old busker and percussionist. “If it's too cold somewhere, we'll get south any way we can. And no one likes to be surprised by rain. Rain isn't nearly as fun when you don't have a dry place to go.”

Piecemeal job-hunting sites like Craigslist are also required browsing if you’re trying to make a living with no permanent place to call home. “For the past 100 years of this lifestyle in America, we found our jobs by following seasonal schedules and asking around for jobs at farmers' markets and farming supply stores, looking at job ads in newspapers, asking door-to-door,” says Huck, adding that things are done very differently today. “I know thousands of hobos, and I don't know a single one that doesn't use Craigslist. It has completely changed how we find work.”

The uses don’t end there. Quain lists Google Maps, Couchsurfing.org and HitchWiki as “indispensable for vagabonds,” while Nuke is still in awe of his smartphone’s power. “I can fit an entire Radioshack from the ’90s and then some in my pocket now.”

Do a Google search for hobo culture and you’ll find a lot about decline: the death of the working-class itinerant, the fall of the Depression-era drifter who never stopped drifting and the end of the heroic hobo celebrated by the likes of the National Hobo Convention in Britt, Iowa. Vice released a documentary in 2012 called Death of the American Hobo. Those “graybeards,” Nuke will tell you, are on the way out, but there isn’t a dearth of culture left in their wake. Itinerants under the age of 35, he says, are forming their own kind of hobo society, one that overwhelmingly keeps up with technology and the times.

Where there used to be “jungles” and “hobohemias,” now the Internet is the place present-day hobos—many of them millennials—go to connect and build a community. Sites little-known among the safely homed—DumpsterMap.com (a map of dumpsters ripe for diving), WiFiFreeSpot.com (a list of free Wi-Fi hot spots), On-Track-On-Line.com (railroad digital scanner frequencies)—are common resources, says Huck, for the vast majority of the digitally connected homeless community. “Prior to 2005 or so, all of this was simply done word-of-mouth, which is how it was done for over 100 years.”

Huck is developing a new hobo code. In terms of the mythology surrounding the homeless, this is a big deal. Read about the romance of hobo culture and you’ll find tons of talk about hobo symbols: a face on the side of a barn means the building’s safe to sleep in; a caduceus on a doctor’s door means the doctor will treat homeless. But for hobos nowadays, that’s all outdated. Huck is part of a project to revamp the code completely and make it more useful for the digitally connected hobo by creating a new set of symbols for things such as “Wi-Fi networks and free outlets.” When I ask if I can publish any of the symbols, though, Huck balks: When hobo codes become commonly known by regulars, it’s a problem. “The codes are for us,” he says, “and if other people see it, they could have clues to our secrets, and the next thing you know, that outlet that was accessible to hobos is now locked up or completely gone.”

Conventional wisdom says the Internet and mobile technology keep us in our own little bubbles, isolated and insular. And while perhaps that’s true for those with homes, Quain says it’s the opposite for hobos. For the itinerant homeless, traveling in groups makes sense for a bevy of reasons: safety, company and economies of scale, especially when it comes to digital devices. “Lots of us travel in groups and share the expense of one phone,” Quain says.

Luckily for Quain and his ilk, the ubiquity of the Internet is making finding fellow “travelers” easier than ever. The curious can head to SquatThePlanet.com and TravelersHQ.org to find vagabonds forming groups, swapping stories and arranging meetings.

Squatters have also enthusiastically embraced the mobile Internet as a means of sharing knowledge—often as a way to fight for their place amid urban real estate development. Frank Morales is a former priest, former squatter and current activist with C-Squat, a squatter advocacy organization in New York. The group works with New York’s homeless men and women who park themselves in unused, often crumbling buildings and fix up the structures in an attempt to turn them into permanent homes.

To do this successfully, squatters need to learn how to bring amenities like electricity and running water into long-neglected buildings—and that, says Morales, is where the Internet becomes indispensable. Where before these skills needed to be shared in person (often at day-long squatter “skillshares”), now they can be digitally transmitted to anyone with a smartphone.

“Technology has really bridged the gap for a lot people around the world who are struggling for housing,” says Morales. Nowadays, activist movements use mass-texting platforms to coordinate occupations of neglected buildings for squatters to use. They also keep email lists that track what squats are in danger and distribute information about new laws that affect squatting. Activist homeless have used digital connections to form a movement that believes, in Morales’s words, “we have a moral obligation as individuals and as a society to support the occupation of spaces that are deteriorating and would otherwise just be rotting away to create housing.”

While no comprehensive survey of homelessness and mobile ownership has been done in the United States, small surveys provide a glimpse of how the trends have grown. A study by the University of Sydney found that 95 percent of Australia’s homeless own a mobile device, while Keith McInnes of the Boston School of Public Health’s study of homeless veterans in Massachusetts found that 89 percent own at least one device. (In Australia, mobile penetration in the general population is 92 percent; in the U.S., it’s 90.) However, “it’s hard to do truly representative studies of homeless persons,” says McInnes. For example, mentally ill homeless living under bridges, or in the woods, are probably less likely to have a cellphone and “less likely to be included in survey, because they are hard to find.”

But as McInnes points out, those who do possess a cellphone have a tool both for survival—and for restoring their sense of humanity. While settled people are usually able to meet the wider world head-on and feel no shame, homelessness carries with it a pervasive, ugly stigma. “Having a mobile phone provides homeless persons with an outward-facing identity that can mask their homelessness,” explains McInnes. “With a cellphone, people you call or who call you don’t know you’re homeless.”

Some, like Huck, have taken this one step further, using their connectivity to promote their lives without a roof and walls as a source of pride. Near the end of our interview, Huck lets me know that he and several others on /r/vagabond have just been featured on an episode of Upvoted, Reddit’s weekly podcast, where they’re celebrated, not stigmatized.

“I’ve found a way to be homeless without starving or begging or sleeping in ditches,” he says. “I’ve become a professional vagabond, and this is the lifestyle that I love.”

flavorcountry: I wonder how many times in a row I can watch...

Burly.ThurrWould watch again.

I wonder how many times in a row I can watch this movie and not get sick of it. Probably a lot. Probably infinity times.

Inspirational Quotes, From Really Bad People

Burly.ThurrWell-executed with the background photos, too.

Just because someone was a terrible person, doesn’t necessarily mean they can’t still inspire people, right? If you didn’t know who the quote was from, these words may make you feel more empowered. But your reaction may change quickly when you find out the author.

Merkin

Burly.ThurrI'm having trouble making space for this, but thought you might get a chuckle, @CC.

January 1: Ecce Foreskin

Burly.ThurrThis is hilarious.

According to Christian tradition, January 1 marks the eighth day of Jesus’ life. Among other things, it is the day on which — following Jewish custom — the Son of Man would have been circumcised. And while the rest of his body would presumably have ascended to heaven on the third day after his gruesome execution, early followers believed it quite possible that he had neglected to retrieve his long-excised foreskin before taking a seat at his father’s right hand.

According to Christian tradition, January 1 marks the eighth day of Jesus’ life. Among other things, it is the day on which — following Jewish custom — the Son of Man would have been circumcised. And while the rest of his body would presumably have ascended to heaven on the third day after his gruesome execution, early followers believed it quite possible that he had neglected to retrieve his long-excised foreskin before taking a seat at his father’s right hand.

For medieval and early modern Christians, Jesus’ foreskin remained an object of peculiar veneration, with as many as eighteen different reliquary nubs of flesh competing for attention and honor. Charlemagne allegedly offered one to Pope Leo III as a gesture of gratitude for being crowned emperor in 800. Another, purchased from a vendor in Jerusalem at the end of the 11th century, was brought back to Antwerp as a souvenir from the first Crusade.

Nearly 300 years later, St. Catherine of Siena purported to wear the foreskin as a ring, while the 13th century Austrian mystic Agnes Blannbekin had an even more unusual relationship with the sacred relic. By Agnes’ own account, she tasted the carne vera sancta — the “true and holy meat” — numerous times during communion. As she revealed to an anonymous Franciscan scribe, she had long pondered the whereabouts of Christ’s foreskin until she experienced a revelation one year on the Feast of the Circumcision.

And behold, soon she felt with the greatest sweetness on her tongue a little piece of skin alike the skin in an egg, which she swallowed. After she had swallowed it, she again felt the little skin on her tongue with sweetness as before, and again she swallowed it. And this happened to her about a hundred times . . . . And so great was the sweetness of tasting that little skin that she felt in all limbs and parts of the limbs a sweet transformation.

Similarly graphic, often erotic accounts helped assure that Agnes’ Life and Revelations would remain unpublished until the 20th century.

Like most Catholic relics, the Holy Prepuce was believed to possess extraordinary powers, including (not surprisingly) the enhancement of fertility and sexuality. And so in 1421, the English King Henry V retrieved one of the rumored foreskins from the French village of Coulombs to aid his wife, Catherine of Valois, in the delivery of their first son. Alas, while the relic may have helped bring the future King Henry VI into the world, it did his father little enduring good. The king died less than a year later, felled by dysentery.

The Reformation helped to undermine Catholic traditions of all kinds, including its centuries of speculation on the provenance and status of Christ’s foreskin. In 1900, the Church issued an edict than any discussion of the Holy Prepuce would result in excommunication and shunning; since the Vatican II reforms of the 1960s, Roman Catholics have not officially recognized the Feast of the Circumcision, though it continues to be observed in some Anglican and most Lutheran churches. The last public appearance of one of Jesus’ alleged foreskins took place in the Italian village of Calcata, which had hosted the tip of the Redeemer’s penis since 1557. Residents of Calcata and Catholic pilgrims continued to celebrate the Feast of the Circumcision until 1983, when thieves absconded with the foreskin and the jewel-encrusted box that contained it. Neither it nor any other alleged foreskins have ever turned up.

The Big Idea: Daryl Gregory

Burly.ThurrLooks fascinating. @CC and Lev because, let's admit, I'm never getting to this.

Your brain: Is it your friend? Or is it something else entirely — something maybe a little less chummy with you than you thought? Ask Daryl Gregory, because he’s given it some thought (with his brain!!!!) for his newest novel, Afterparty.

DARYL GREGORY:

Your brain is lying to you. Not just about the small stuff, like when it makes you fall for an optical illusion, messes with your sense of time, or creates a gorilla-size gap in your perception when it’s busy concentrating on something else.

Your brain is also lying about the big stuff, the most fundamental aspects of being human. It starts with the illusion that there’s a “you” behind your eyes, and independent “self” that has something called free will. Folks like Daniel Dennett argue that free will is just a feeling of control. And Dan Ariely, the guy who wrote Predictably Irrational, can supply plenty of examples of how our “rational” decision-making can be shaped by things as simple as changing the design of a form at the DMV.

But evolution has also shaped our brains to affect the way we make moral decisions. Consider the well-known thought experiment, the Trolley Problem. A runaway trolley is coming down the track toward five people. You can pull a lever to divert the trolley onto another track, where a single person is standing. Do you kill one person to save five?

The answers people give can vary simply by the story you tell about the singleton who would die. Is he a fat man you’d have to push onto the track yourself, a villain who “deserves it,” or an unsuspecting guy sleeping in his hammock? Because we evolved as social apes, some actions just feel more wrong, even if the moral calculus is the same.

Your brain, basically, is Mr. Liar McLiarpants. And that’s the big idea behind Afterparty.

The story takes place in the very near future. (If you want to write about the present in a way that won’t feel quaint in ten minutes, write near-future SF. It’s just mainstream fiction with the sell-by date scraped off.) To show what life is like a few years into the designer-drug revolution, I made up a few technologies that are pretty much doable now, chief among them the ChemJet.

Here’s how you build one. Take something like a 3D printer. Replace the input material with packets of pre-cursor chemicals (phenethylamine’s a good building block) that you buy semi-legally online. Next download recipes for smart drugs from a vibrant community of bio-hackers. Or make your own, and beta test the results on you and your friends.

Obviously there are going to be some interesting consequences of desktop drug design, some of them horrible.

Lyda Rose, the main character in the book, is a good example of both sides of that bio-hacking coin. She’s a former neuroscientist who discovers that the drug she helped create ten years ago, and thought she buried, is back on the streets, being printed by underground churches.

The drug goes by the name Numinous, and for good reason. Take a little, and you get that mystical feeling that William James described in The Varieties of Religious Experience, and that’s been experienced by humans throughout history. (Some people with temporal lobe epilepsy have it every day.) It has many qualities, but the main one is that you feel like you’re in contact with something wholly outside your self—a divine other.

That’s what happens if you take a little Numinous. Overdose on the drug, however, and you might wake up with a deity permanently installed in your brain—your own personal Jesus.

Ten years before the story starts, Lyda and the co-creators were all given a massive dose of Numinous against their will. (Who did that to them, and why, is one of the mysteries in the book.) Each of the survivors now has their own “divine” presence living with them, and Lyda’s is Dr. Gloria, an angel in a white lab coat. Lyda, as a scientist, knows that Dr. Gloria’s a hallucination. But the other side of the coin is that the good doctor is also good for her; Lyda’s a better person when Gloria is advising her and soothing her.

That’s the main question the book asks: if someone invented a drug that made you technically insane, but helped you to be kinder and more connected to your fellow humans, would you take it? And what happens when other people decide they should convert you for your own good?

If you don’t want to wait for the future to get your dose of chemical evangelism, you can always take the long road. Every day, millions of people meditate, pray, sing whirl, and chant, chasing that feeling of the numinous. Whether it’s God (or some other higher power) communicating with them, or whether it’s just the brain fooling them with its own recipe of chemicals, that’s a question that each person—and his or her brain—has to work out for themselves.

As for me, I trust my brain about as far as I can throw it. (Which isn’t far, because skull.) But I think of it as living with a charming sociopath. Some of the stories it tells become more interesting when you know they’re lies.

—-

Afterparty: Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound | Powell’s

Read an excerpt. Visit the author’s blog. Follow him on Twitter.

You'll Never Look At An Apple Watch The Same Way After This "Pulp Fiction" Parody

A Helmet Cam Video of a Cyclist Hilariously Narrating a Frightening Descent Down a Mountain Bike Race Course

Bicycle racing team manager Claudio Caluori narrates his frightful descent down a mountain bike race course in France in this breathtaking yet humorous helmet cam video. The video was shot in Lourdes on a downhill course at the 2015 UCI Mountain Bike World Cup, a competition that took place last weekend.

via Digg

Photo

Burly.Thurr"thank you for saving that book instead of my sister, god."

Frozach Submitted

Burly.ThurrOh no, the look on Kidney's face as he's handing over the stones to urinary bladder. Shudder.

Expanded from

Expanded from