Yuval Pinter

Shared posts

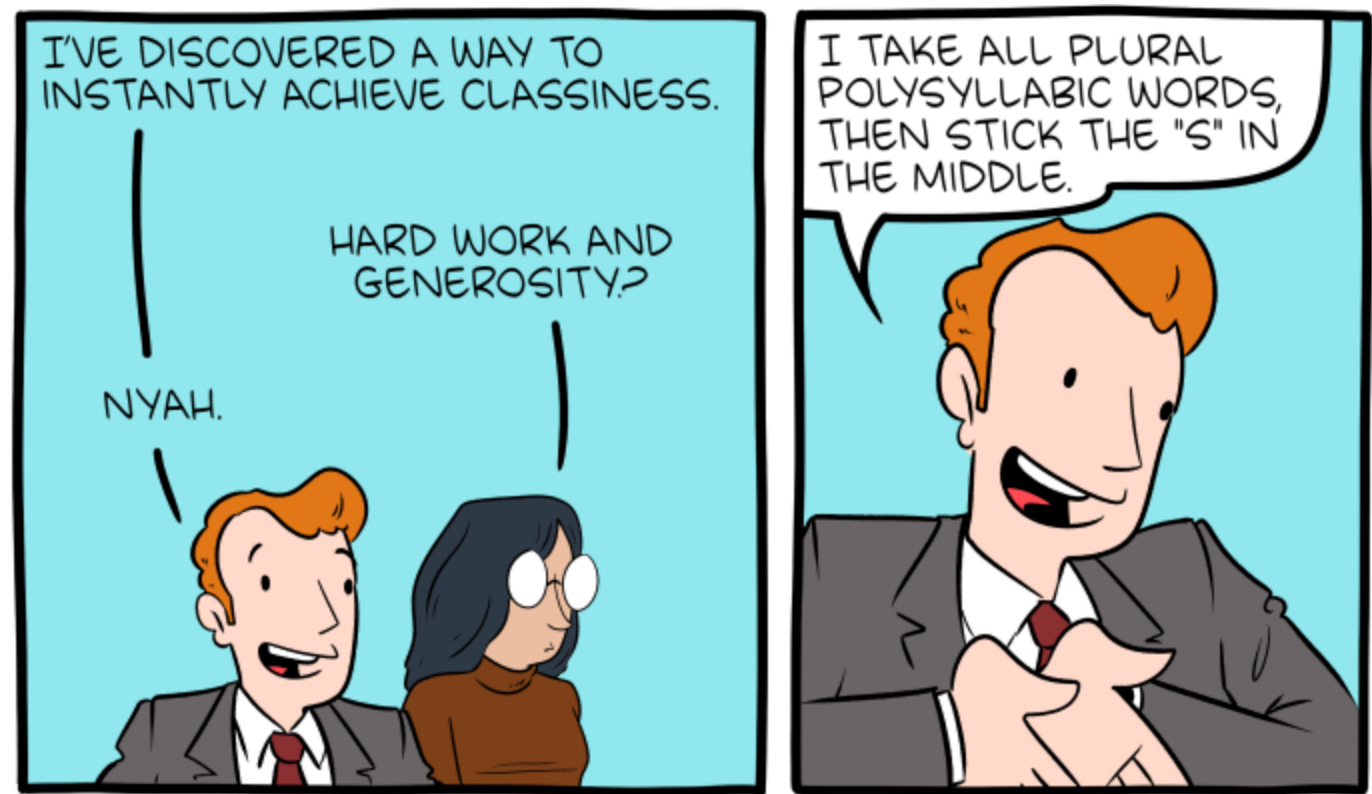

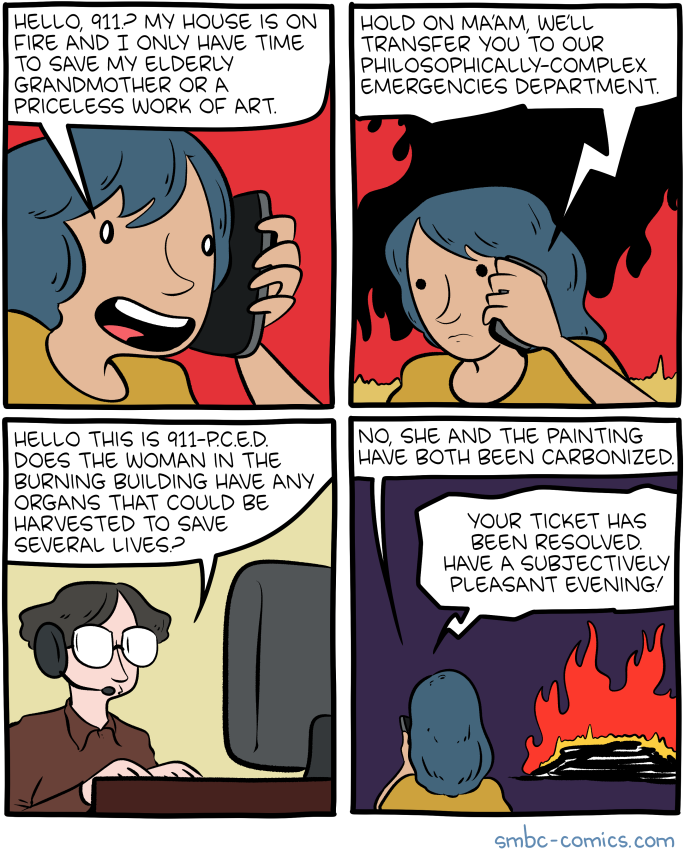

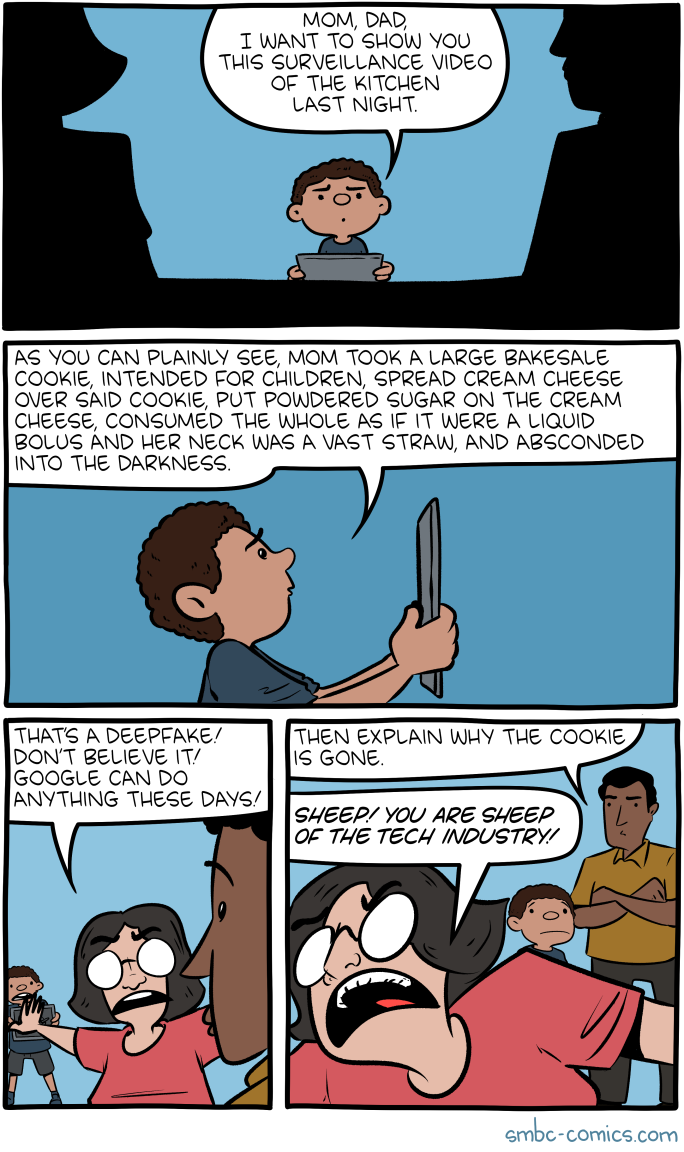

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - PCED

Yuval Pintergood bonus panel

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

95% of PCED calls will be eliminated as soon as we have self-driving trolleys.

Today's News:

Snowy Hunters Everywhere.

Less than a week into the existence of this blog, I posted about the workings of coincidence (see also Apophenia, from 2005); now I’ve got another splendid example. For over a month now I’ve been hacking away at Sokolov’s Между собакой и волком (see this post) with the invaluable help of (inter alia) Boguslawski’s valiant translation Between Dog and Wolf; I quote the following from his introduction (p. xxi):

The best example of a recurrent visual image is the ekphrastic description of Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow, which provides a detailed portrayal of the setting of the novel in chapter 2 and is skillfully repeated in Note XVII. It becomes a source of many reappearing images in the novel (birds, boats, skaters, a frozen river and ponds, hunters and hunting dogs, a tavern) and, in addition, provides a connection to the theme of the seasons, since Bruegel created the famous painting as a part of the series called Months and depicted in it activities common in December and January.

Well, Barnes & Noble is having a 50% off sale on all Criterion Blu-rays and DVDs through August 1, and being an aficionado of Criterion’s superb editions I put together an order that included one of my favorite movies, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Зеркало (Mirror), and the last movie by another of my favorite directors, Abbas Kiarostami’s 24 Frames. I knew nothing about the latter, but Criterion describes it enticingly:

Setting out to reconstruct the moments immediately before and after a photograph is taken, Kiarostami selected twenty-four still images—most of them stark landscapes inhabited only by foraging birds and other wildlife—and digitally animated each one into its own subtly evolving four-and-a-half-minute vignette, creating a series of poignant studies in movement, perception, and time. A sustained meditation on the process of image making, 24 Frames is a graceful and elegiac farewell from one of the giants of world cinema.

So I was excited to get the package today, and I tore off the plastic coverings and checked out the beautifully illustrated booklets they tuck into each box. The one for Mirror reminded me of an element I’d forgotten: “Alexei’s anecdotal recollection of a snowy day during the war prompts a visual echo of the composition of Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow.” Huh, I thought. Then I turned to the Kiarostami and found in Bilge Ebiri’s essay:

The first frame begins with Dutch master Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s immortal sixteenth-century painting Hunters in the Snow, a winter scene of a group of men and dogs looking over a small village beside a frozen lake. Slowly, Kiarostami’s digital embellishments emerge. Smoke rises from a chimney. A bird flits among the branches of a tree. A dog starts sniffing around. A herd of cows lumbers along in the distance. But amid all this movement, the figures of the original painting stand motionless. The hunters carry the same poses they did in 1565. Some birds may hop among the trees, but one remains frozen in the sky, captured midflight by Brueghel 450 years ago, its wings spread out forever.

I’m not saying it Means anything, but tell me that isn’t weird.

Bunin’s Loopy Ears.

Another break from Sokolov, another great Bunin story (see this post): his 1916 “Петлистые уши” [Loopy Ears] (published in 1917, in Slovo 7) is far more interesting than it is made to sound in the usual summary (“man murders prostitute”). Yes, in the last sentence we learn that a prostitute has been murdered, but that’s just the donnée on which the story is based (apparently it was sparked by Bunin’s having read a newspaper account of such a killing). Bunin was polemicizing with his least favorite writer, Dostoevsky (one of the things he and Nabokov had in common), replacing the loquacious and tormented Raskolnikov with the sullen Adam Sokolovich, a former sailor who spends his time wandering around Petrograd, looking into shop windows, and hanging out in dives. At the start of the story we see him in such a dive, in the down-at-heels neighborhood near Five Corners (Пять углов, associated with Dostoevsky), haranguing a couple of sailors about the depravity of mankind (I quote the translation in Thomas Gaiton Marullo, “Crime without Punishment: Ivan Bunin’s ‘Loopy Ears’,” Slavic Review 40.4 [Winter 1981]: 614-624 [JSTOR]):

It is time to abandon the fairy tale concerning pangs of conscience, those moments which supposedly haunt the murderer. People have lied enough as it is — as if they shudder from the sight of blood. Enough of writing novels about crimes with their punishments; it is time to write about crimes without any punishments at all. The outlook of the criminal depends on his view of the murder — whether he can expect from his crime the gallows, reward, or praise. In truth, are they tormented, are they horrified, those who accept ancestral revenge, duels, war, revolution, and executions?

He goes on to mention the famous (in his day) French executioner Louis Deibler (who chopped off “exactly five hundred heads”), the violence in popular literature (including James Fenimore Cooper and the Bible), and the horrors of World War I (Bunin was writing two years into the war): the mass murder of Armenians by the Turks, the poisoning of wells by the Germans, and the bombing of Nazareth (I can find no reference to this — maybe a war rumor in 1916?). He concludes that it was only Raskolnikov who was ever tormented by murder, and only because his spiteful creator insisted on sticking Christ into all his trashy novels (“по воле своего злобного автора, совавшего Христа во все свои бульварные романы”). By the time he leaves his indifferent companions and heads out into nighttime Petrograd, oppressed by a wintry fog, half the story has gone by, and since Bunin does not waste sentences, we obviously need to give due weight to that conversation.

At this point we get a wonderful travelogue (Mark Aldanov quotes it at the start of his 1933 “Об искусстве Бунина” [On the art of Bunin] and says “I don’t know any description in Russian literature equal to it,” concluding his detailed analysis of the story by calling it the best of Bunin’s short works): Sokolovich walks down Nevsky Prospect, seeing a fallen horse by the famous Palkin restaurant (at #47 since 1874), crossing the Anichkov Bridge over the Fontanka, seeing the reddish gleam of the clock on the City Duma, reaching the Kazan Cathedral and entering the Dominique Cafe (that translation of the article in the Encyclopaedia of St. Petersburg for some reason uses the spelling “Dominic,” though they correctly give the name of the Swiss founder as Dominique Ritz Aport; the 1914 Baedecker calls it Dominique), where he sits in a dark corner, orders a black coffee, and fends off an undercover cop. These pages are clearly meant to compete with similar descriptions of the city in Gogol, Dostoevsky, and Bely, and they do so brilliantly. At 1 AM the restaurant closes and he goes back out onto the frigid street:

At night in the fog Nevsky is terrifying. It is deserted, dead, the haze that befogs it seems a part of that Arctic haze that comes from the end of the world, that place where something incomprehensible to human reason is hidden and that is called the pole.

Ночью в туман Невский страшен. Он безлюден, мертв, мгла, туманящая его, кажется частью той самой арктической мглы, что идет оттуда, где конец мира, где скрывается нечто непостижимое человеческим разумом и называется Полюсом.

(I thought “в туман” must be a typo for “в тумане,” but all editions seem to have it.) That’s one of the many passages I marked in the margin as worthy of repeating aloud and enjoying repeatedly, and I quote it here as a sample — the story is full of such writing, and for anyone who loves good prose it’s worth learning Russian just to read Bunin.

At this point he sees the prostitute, Korolkova, calls a cab, takes her to a cheap hotel in the outskirts (“в таинственную глушь ночных столичных окраин”), snaps at the sleepy номерной (valet/concierge/boots), orders champagne and grapes, and leaves early in the morning (upon which the valet enters the room and sees the body). It’s a grim description of dehumanized humans and efficiently produces the effect Bunin wanted, but it’s not what the story is “about.” It is not, as Victor Terras once called it, “a chilling study of sadism” — or rather, that’s merely one of the many things it is, and one of the least interesting. The story is about the story, all of it; like a poem, it’s a machine made of words.

I should mention the title, which gives almost as much trouble as Bad Grass. The first word, петлистый, is a perfectly normal (though uncommon) adjective derived from петля ‘loop; noose’; Nabokov — who was uncommonly fond of it, using it in his story Возвращение Чорба [“The Return of Chorb”: петлистые тени листьев], in the novels Камера обскура [Laughter in the Dark: петлистое шоссе] and Дар [The Gift: с петлистыми «рцы» и «покоями»], in the memoir Другие берега [eventually transmogrified into Speak, Memory: в петлистых тенях дышащей в такт аллеи], and several times in his translation of Lolita [любимые, петлистые, детские каракули; воспользоваться петлистым, ленивым шоссе Зед; пошел сквозь петлистый огонь солнца] — rendered it in English as “loopy,” and that’s probably the best translation here (though it can also be Englished as “twisting,” “winding,” “meandering,” and the like). The problem is that the title comes from Sokolovich’s tavern conversation, where he calls himself a degenerate (выродок) and says that you can recognize degenerates, geniuses, vagrants, and murderers by their loopy ears, which resemble the loop/noose with which they’re hanged: “У выродков, у гениев, у бродяг и убийц уши петлистые, то есть похожие на петлю, вот на ту самую, которой и давят их.” And since the Russian plays on the resemblance to the word for the hangman’s noose, Robert Bowie, who translated it for the collection Night of Denial: Stories and Novellas, felt impelled to render the title “Noosiform Ears.” Come on, dude. For that matter, he’s not good on names in general: he calls Deibler “Deblair” and Dominique “Dominick.” But it doesn’t look like a bad translation, and since there are so few English versions of Bunin out there, I recommend it.

Oh, and one last thing. Marullo quotes a Soviet critic as follows:

L. Nikulin writes that Bunin was one of the few Russian writers of the age who did not subscribe to militaristic tones in his writings. Nor did he see the war as providing the potential for the spiritual rebirth of mankind (see L. Nikulin, “Ivan Bunin,” in Ivan Bunin, Sobranie sochinenii, 5 vols. [Moscow, 1956]…).

Good for Bunin! War (as we used to say) is not healthy for children and other living things.

לא כזה גליק גדול

Yuval Pinterכותרת השנה

"While I personally enjoyed this contribution, I cannot escape the sense that this is much ado about..."

ארמזים מאולצים בימי קורונה

Yuval Pinterweeeee're back?

שלום! אנחנו "דגש קל", בלוג העוסק בענייני שפה. מאז ינואר 2020 לא יצא לנו לפרסם רשומה, ומאז מרס 2020 *מחווה בנפנופי ידיים סביב*, אך עתה בשלה העת והגיע השיימינג העצמי עד נפש, לכן אוריד מעל לבי את שהיה לי לכתוב כבר בראשית תקופת המגפה ואולי ייפרץ הסכר להמשך פוסטיאדה כימינו כקדם.

התופעה הסוג-של-לשונית הראשונה שהטרידה אותי ברמת פוסט-לדגש היתה קלישאה שהחלה לפשות, מעין סנובון או תבנית או אלוהים יודע מה, מהצורה X בימי קורונה. בא לי להגיד שהמופעים הראשונים השמו במקום המשתנה את המילה "אהבה", כי זו הווריאציה הברורה ביותר על הספר "אהבה בימי כולרה" למארקס, אבל קשה לבדוק דבר כזה.

אני כן יודע שהתבנית התפשטה בקצב מסחרר: כבר באפריל 2020 הסתובב סרט בזה השם. מאידך גיסא, נראה שהיא נמאסה די מהר. לפי התרשים להלן, הנוגע לגרסה העברית שלה, העם בציון התעשת תוך כחודשיים.

מעניין אותי לדעת אם החצי-קירבה הפונטית של המילה קורונה לכולרה שיחקה פה תפקיד. האם היינו חוטפים גל של "הוראה בימי סארס"? "השקעות בימי אבולה"? "וולנס בימי צהבת נגיפית"? יש דרך מדעית אמינה לבדוק, אבל בואו נוותר עליה בשלב זה.

הערה מנהלתית: אם עוד יש לנו קוראים, אפשר להגיב עם הצעת נושאים לפוסטים בימי פוסט-קורונה, לשלוח בהמייל, להתנדב לרשומת אורח, וככל הימינו-כקדמים כקדם.

"If this was taken from a successfully defended thesis, as it appears to have been, then he should..."

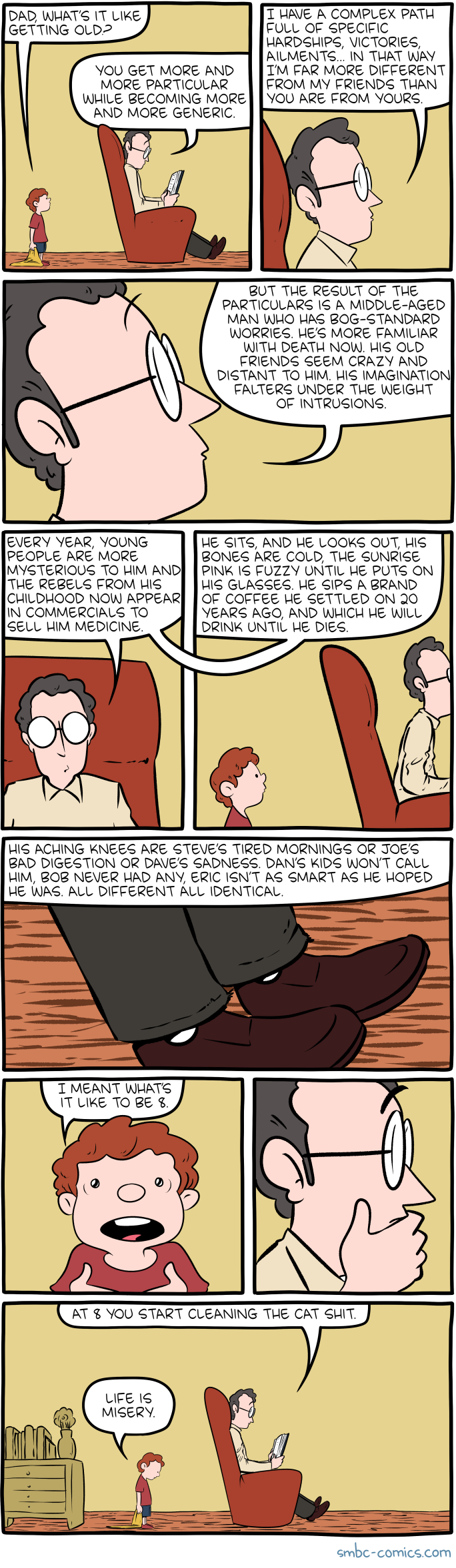

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Old

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

This is one of this comics that prompts very nice 'are you okay?' emails, but honestly I'm just over here giggling.

Today's News:

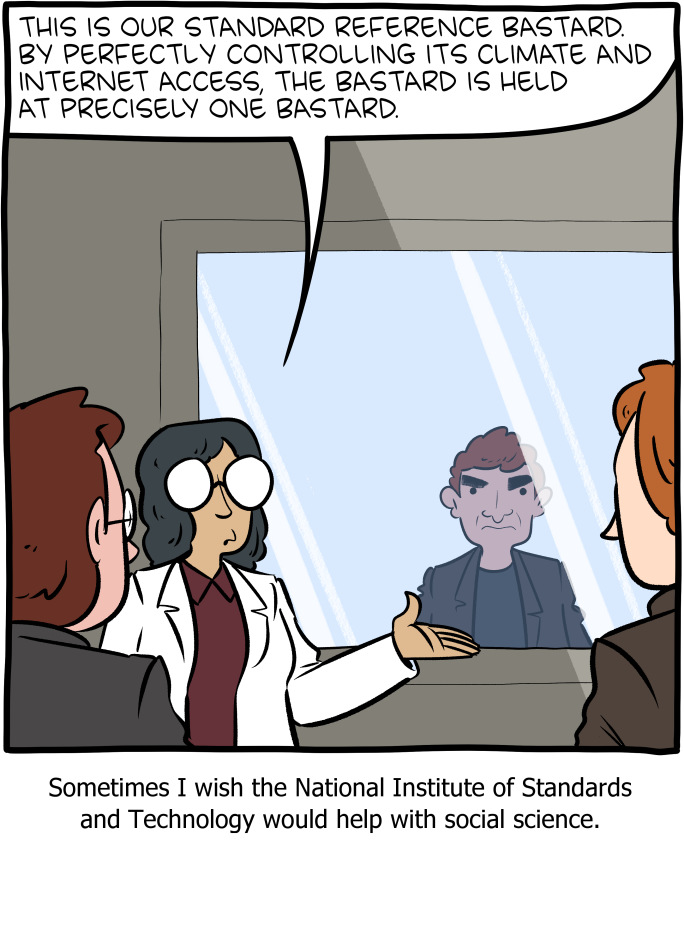

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Reference

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

The reference c-word is held at a stable level of inebriation at an Edinburgh pub.

Today's News:

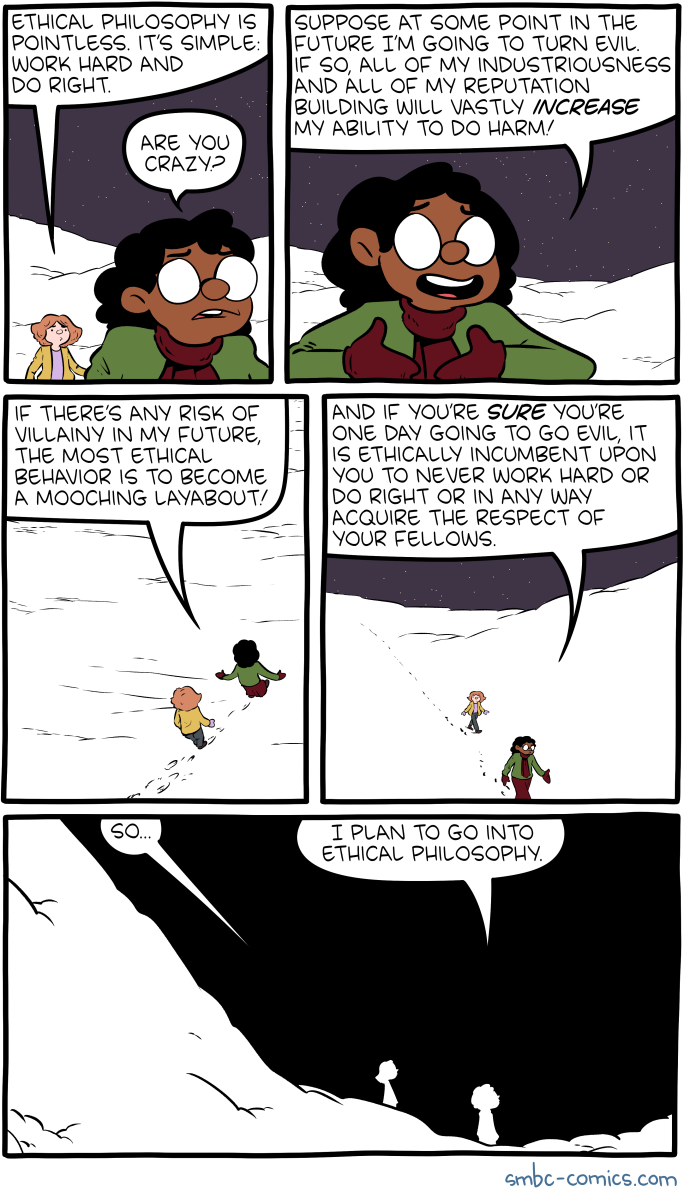

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Ethics

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

Someone on patreon pointed out that Hitler tried to go into painting, and it's just ruined my whole point.

Today's News:

English Was Brilliant.

I’m finally reading Boris Fishman’s novel A Replacement Life (see this 2017 post), and I thought this passage was postworthy (the viewpoint character, Slava, is the only one in his immigrant family who can read English, so the mail is turned over to him for interpretation: “Was this a letter from James Baker III alerting the Gelmans that a tragic mistake had been made and the family would have to return to the Soviet Union?”):

The letter was given to Slava. His fingers were small enough for the Bible font and onionskin pages of the brick dictionary they had procured from a curbside, somebody who had learned English already. As the adults shifted their feet, leaning against doorjambs and working their lips with their teeth, he carefully sliced open the envelope and unfolded the letter inside, his heart beating madly. He was all that stood between his family and expulsion by James Baker III. America was a country where you could have Roman numerals after your name, like a Caesar.

As the adults watched, Slava checked the unfamiliar words in the bricktionary. “Annual percentage rate.” “Layaway.” “Installment plan.” “One time only.” “For special customers like you.” The senior Gelmans waiting, Slava was embarrassed to discover himself mindlessly glued to certain words in the dictionary that had nothing to do with the task at hand. On the way to “credit card,” he had snagged on “cathedral,” its spires —t, h, d, l—like the ones the Gelmans had seen in Vienna. “Rebate” took him to “roly-poly,” which rolled around his mouth like a fat marble. “Venture rewards” led him to “zaftig,” a Russian baba’s breasts covering his eyes as she placed in front of him a bowl of morning farina. Eventually, he managed to verify enough to reassure the adults that, no, it didn’t seem like a letter from James Baker III. The senior Gelmans sighed, shook their heads, resumed frying fish.

Slava remained with the bricktionary. Hinky, lunker, wattles. Taro, terrazzo, toodle-oo. “Levity” became a Jewish word because Levy was a Jewish surname in America. “Had had”—knock-knock—was a door. A “gewgaw” was a “gimcrack,” and a “gimcrack” was “folderol.” “Sententious” could mean two opposite things, and wasn’t to be confused with “senescent,” “tendentious,” or “sentient.” Nor “eschatological” with “scatological.” This language placed the end of the world two letters away from the end of a bowel movement.

Russian words were as stretchy as the meat under Grandmother’s arm. You could invent new endings and they still made sense. Like peasants fidgeting with their ties at a wedding, the words wanted to unlace into diminutives: Mikhail into Mishen’ka (little Misha), kartoshka into kartoshechka (little potato). English was colder, clipped, a brain game. But English was brilliant.

Reginald Foster, RIP.

Stu Clayton sent me Margalit Fox’s NY Times obituary of a remarkable Latinist; it begins:

Reginald Foster, a former plumber’s apprentice from Wisconsin who, in four decades as an official Latinist of the Vatican, dreamed in Latin, cursed in Latin, banked in Latin and ultimately tweeted in Latin, died on Christmas Day at a nursing home in Milwaukee. He was LXXXI. His death was confirmed by the Vatican. He had tested positive for the coronavirus two weeks ago, The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported.

A Roman Catholic priest who was considered the foremost Latinist in Rome and, quite possibly, the world, Father Foster was attached to the Office of Latin Letters of the Vatican Secretariat of State from 1969 until his retirement in 2009. By virtue of his longevity and his almost preternatural facility with the language, he was by the end of his tenure the de facto head of that office, which comprises a team of half a dozen translators.

If, having read this far, you are expecting a monastic ascetic, you will be blissfully disappointed. Father Foster was indeed a monk — a member of the Discalced Carmelite order — but he was a monk who looked like a stevedore, dressed like a janitor, swore like a sailor (usually in Latin) and spoke Latin with the riverine fluency of a Roman orator.

He served four popes — Paul VI, John Paul I and II, and Benedict XVI — composing original documents in Latin, which remains the Vatican’s official language, and translating their speeches and other writings into Latin from a series of papal languages. (He was also fluent in Italian, German and Greek.)

As you can see, the obit itself is pleasingly written; a couple more samples:

Father Foster was unabashedly bibulous (from the Latin bibēre, “to drink”); combustible (< combūstibilis); dyspeptic (a Greek word, but indisputably apposite); cacophonous (his was a partly silent order, a state of affairs he more than made up for outside the monastery); undiplomatic (in interviews, he had all manner of advice for his exalted bosses, none of it solicited); and more than a trifle insurrectionist (in the privacy of his monastery room, he told The Minneapolis Star Tribune in 1998, he liked to say Mass attired as he was the day he was born). [...]

The Vatican, at any rate, found it could not do without him. When there was an encyclical to be translated; a congratulatory letter to a cardinal or bishop to be written; a contemporary term, like “microchip,” that sang out for a Latin equivalent (he chose “assula minutula electrica”: “tiny amber wood chip”); or, after John Paul II approved a no-smoking ordinance in Vatican City, a sign to be posted (proposed wording: “Vetatur Fumare”), it turned again and again to Father Foster. […]

“You do not need to be mentally excellent to know Latin,” he said in the Telegraph interview. “Prostitutes, beggars and pimps in Rome spoke Latin, so there must be some hope for us.”

The obit is behind a paywall; fortunately, Trevor Joyce sent a couple of links that are free to all comers: Fr. John Zuhlsdorf’s blogpost R.I.P. – Fr. Reginald Foster, OCD, which has some touching personal reminiscences, and a three-minute video Senior Vatican Priest – Father Reginald Foster – interviewed by Bill Maher, in which Foster is very cheeky indeed, to Maher’s delight. Foster has been mentioned here before, in 2004 (“Latin’s loudest advocate in the modern world”) and 2017 (“I have to say, Foster’s insistence on ‘total philological mastery’ sounds off-putting to me”). Stu has ordered Foster’s 2016 book Ossa Latinitatis Sola ad Mentem Reginaldi Rationemque (“The Mere Bones of Latin According to the Thought and System of Reginald”); I trust he will give us a report in good time.

Comic for 2020.12.27

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Surveillance

Yuval Pinterbonus panel.

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

Later it turns out the Dad has masterminded everything.

Today's News:

“History of Swear Words” on Netflix

We’re pleased AF to let you know that “History of Swear Words,” will launch on Netflix January 5, 2021. The series—six 20-minute episodes—will consider the etymologies, false etymologies, and usage of six classic swears: fuck, shit, dick, bitch, pussy, and damn.

We’re especially pleased that one of our Strong Language co-fuckers, lexicographer Kory Stamper, was one of the consultants for the show. The other experts include cognitive scientist and author of What the F Benjamin Bergen; linguist Anne Charity Hudley; professor of feminist studies Mireille Miller-Young; film critic Elvis Mitchell; and author of Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing Melissa Mohr.

Nicolas Cage will host.

More details here. And let’s hope for a second season so we can delve into asshole, cunt, cocksucker, and other sweary faves.

like conjugating verbs, but worse

Linguistics, University of Chicago

Person marking in Washo as Agreement and clitic movement

ML@GT Further Establishes Itself in Natural Language Processing Community

Over the years, the Machine Learning Center at Georgia Tech (ML@GT) has steadily been increasing its presence in the natural language processing (NLP) community. With a few new hires this fall and a big performance at this year’s Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), ML@GT is becoming a major player in the field.

With 10 papers accepted to the main EMNLP conference and three papers at a new, coinciding sister publication called Findings of EMNLP, Georgia Tech researchers are tackling problems like how to summarize text and interpreting how persuasive language impacts domains advertising and argumentation.

Diyi Yang, an assistant professor at ML@GT and the School of Interactive Computing leads the Georgia Tech group with six accepted papers. Yang is also the area chair for the interpretability and analysis of models for the NLP track.

“EMNLP is one of the most prestigious conferences in NLP, and one of the best conferences for the interaction of machine learning and NLP. Georgia Tech’s NLP program is emerging and our presence at EMNLP is a strong signal of it,” said Yang.

Yang also noted that many of the papers accepted from her lab, Social Language and Technologies (SALT), are from first-time authors who are also first-year Ph.D., master’s, or undergraduate students.

“It is a great recognition of our students’ passion, efforts, and their research impact in this NLP space. I feel proud of them and excited about more high-impact and fun projects that will come next!” said Yang.

Outside of accepted papers, Yang is also an invited speaker for the 4th Workshop on NLP and CSS. ML@GT Ph.D. student Yuval Pinter is co-organizing BlackboxNLP, a workshop at EMNLP dedicated to model interpretability. IC Associate Professor Alan Ritter and IC Assistant Professor Wei “Coco” Xu are co-organizing the Workshop on Noisy Text. Ritter and Wei are also involved with the language generation track as a senior area chair for information extraction and area chair, respectively.

Overall, EMNLP accepted 602 long papers and 151 short papers, with a 22.4 percent and 15.5 percent acceptance rate respectively. The conference will take place online Nov. 16 through 20. For more information on ML@GT’s presence at EMNLP 2020, visit ML@GT at EMNLP.

Press Contact:

Allie McFadden | Communications Officer | allie.mcfadden@cc.gatech.edu

Lawyers set to be executed

Melissa Jeltsen, "Lawyers For Mentally Ill Woman Set To Be Executed By U.S. Contract Coronavirus", Huffpost 11/12/2020.

"U.S. Contract Coronavirus" would be an innovative method of execution, but not the most unexpected event of the year.

[h/t Rick Rubenstein]

Angle of Incidence.

This is actually based on the Kaverin novel I posted about yesterday, but that post was long enough already, so I figured I’d let this stand on its own. At one point Liza is having coffee in the Rotonde with her husband Georgii and Kostya, the love of her life, who’s visiting from Russia; she and Kostya have a few precious moments alone when Georgii wanders off too far to hear, and they have the following exchange (Kostya speaks first):

— Он не умеет читать по губам?

— Нет. Кроме того, для нас с тобой угол падения не равен углу отражения.“He doesn’t know how to read lips?”

“No. Besides, for us the angle of incidence isn’t equal to the angle of reflection.”

The line about the angles is repeated twice more in the course of the novel, so it’s not merely a passing remark (and it occurs to me that it’s probably not irrelevant to the titular mirror). It may seem a bit random to the reader unfamiliar with its antecedents, but it is part of a tradition — a meme, as we say nowadays — in Russian literature. The immediate source is Marina Tsvetaeva’s long essay on the painter Natalia Goncharova (both she and especially Tsvetaeva are characters in the novel); she writes that the world is reflected косвенно (‘indirectly, obliquely’) in Goncharova’s paintings, and continues:

То, что я как-то сказала о поэте, можно сказать о каждом творчестве: угол падения не равен углу отражения.

What I once said about a poet could be said about all creative work: the angle of incidence is not equal to the angle of reflection.

This, of course, is a poetic contradiction of the Law of Reflection (“the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection”; for detailed explanations, see this Stack Exchange thread), but why does she bring it up? Because it was in one of the most important Russian works about painting, Merezhkovsky’s Воскресшие боги. Леонардо да Винчи (Resurrected Gods: Leonardo da Vinci; see this LH post) — describing Leonardo’s ability to discuss frightful subjects calmly and dispassionately, Merezhkovsky writes:

Говоря о мертвых телах, которые сталкиваются в водоворотах, прибавил: «изображая эти удары и столкновения, не забывай закона механики, по которому угол падения равен углу отражения».

Speaking about dead bodies colliding in whirlpools, he added: “in depicting these blows and collisions, do not forget the mechanical law according to which the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection.”

Again, this is repeated several times; for example, when Leonardo realizes that waves in water, sound waves, and light all obey the same laws, he exclaims:

«Единая воля и справедливость Твоя, Первый Двигатель: угол падения равен углу отражения!»

“Thy will and justice are one and indivisible, First Mover: the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection!”

(You can see the other occurrences at this National Corpus page.) But two decades earlier, Turgenev had used it in a very different way in one of his poems in prose, Истина и Правда [Scientific truth and real truth], where one person says scientific truth is vitally important and the other mocks him, asking if he can imagine someone running into a gathering and saying excitedly:

«Друзья мои, послушайте, что я узнал, какую истину! Угол падения равен углу отражения! Или вот еще: между двумя точками самый краткий путь — прямая линия!»

“Friends, listen to what I’ve just found out, what truth! The angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection! Or this: the shortest path between two points is a straight line!”

Here it represents the height of banality, on the level of 2 × 2 = 4 (which of course has its own Russian literary history). Why did this law of physics become a meme in Russian and not in English? I speculate because the Russian words are normal, everyday words: падение, translated in this context as “incidence,” is the normal word for ‘fall(ing)’ (both physical and in the Fall of Man), so the law sounds like a popular saying.

Thirst of the Dead

Here are more zombies. And there’s still lots of time to enter my Halloween contest!

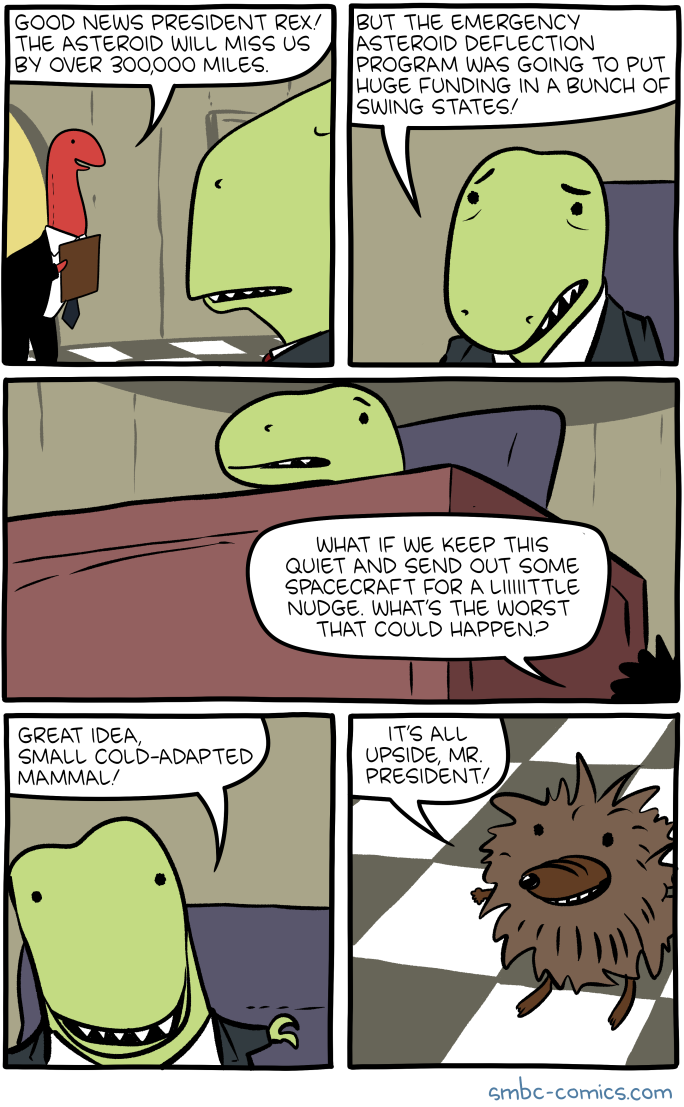

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Nudge

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

Someone on patreon pointed out that the small mammal sure looks like the infamous hedgefox of comics past, which makes perfect sense in context.

Today's News: