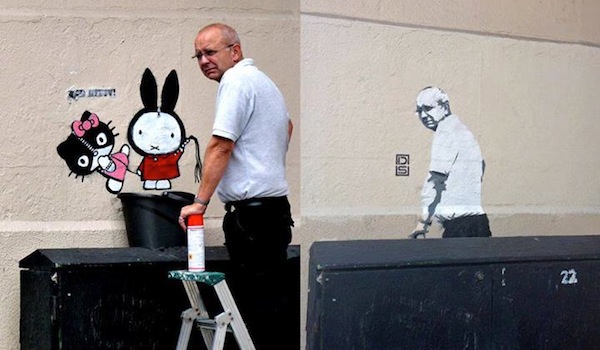

Illustrations by Cei Willis

It was when they manhandled him onto the table, tethered him to a water pipe coming out of the ceiling, and pulled his pants down to his ankles that I experienced a change of heart. For weeks I’d been consumed with hatred for the man on that table. But it’s funny how your perspective changes when someone is about to be tortured, especially when you’re the one that put him there.

It had begun, like many tales of misadventure, in that most anarchic staging post for travel: the Tanzanian bus station. Ever been to one? This is how it goes: The long-distance buses tend to leave at dusk or before; schedules are mind-bogglingly irregular; a tourist tax on the price of a ticket is all but inevitable. Like transport hubs the world over, they’re a magnet for the wretched, the transient, and the dispossessed. And you endure it all for the privilege of cramming yourself into a bus driven by some prepubescent boy-racer in a country with a traffic-accident rate six times worse than that of the UK.

Arriving in the southern town of Mbeya at 10 PM one balmy evening in May, shattered after a 14-hour kick from Dar es Salaam and in a hurry to reach Malawi, I’d steeled myself for another onslaught. At the bus station, arrayed on an expanse of cracked concrete, an collection of ticket offices advertised destinations with a chaotic matrix of handwritten signs and sheets of printer paper pinned to the wall.

And then—and this should have been warning number one—the guy came to me. He was a stocky guy with a wolf's smile and these protruding eyes that gave him the look of a toad. He wore a white polo shirt with a label on the breast that read "AXA Coach Service"—one of Malawi’s biggest people carriers. We’ll call him "Mwizi," which is Swahili for "thief." He showed me bus tickets reassuringly marked with the blocky AXA logo that promised to take us all the way from Mbeya to Blantyre—Malawi’s commercial hub—620 miles south. Too good to be true.

Sure enough, the next morning it all felt wrong. Mwizi seemed agitated as he half-cajoled, half-bundled us onto a minibus bound for the border post. And as it pulled away, through the window, I could see something in his eyes—guilt, I figured later, for when I got to the Malawian side of the border there was no connecting bus to Mzuzu. The tickets were fake. And having gotten our passport stamps and relinquishing our Tanzanian visas, it would have cost us more than the price of the ticket to return—the perfect swindle.

Getting scammed is an everyday feature of the tourist experience, but this was a whole new level of chicanery. It wasn’t the loss of money that pissed me off, but the bare-faced charade, the smiles and reassurances. Not that we were alone: Relaying our tale of woe to other travelers in Malawi, it soon became clear that just about every credulous backpacker taking that route had fallen for the same routine, performed either by Mwizi or others operating just like him.

But poor Mwizi hadn’t reckoned on one thing. I was due to travel up to Rwanda for an assignment in a month’s time, and to get there I needed to pass back through Mbeya. I would be back, and I would have my vengeance.

One month later, I arrived at Mbeya Station at dusk. Looking back, I wonder what retribution I could have pursued to avoid what came later. Perhaps I could have been more subtle—I could have waited for a sight of Mwizi, then ambushed him to demand my money back, and perhaps given him a slap. But I didn’t do subtle. Instead, I simply stormed over to the ticket offices like a wronged colonial big man, shamefully exploiting my white skin, and prowled about barking maniacally until some policemen noticed me and waddled over to investigate.

Word spread. The culprit was found, bundled through a sea of onlookers by many hands. When he saw me, his eyes fell to the ground. Without ceremony, Mwizi was roughly handcuffed and frogmarched north through unlit backstreets. “I had half a mind to just stampede the office and smash your face in,” I spat, sidling up to him as we walked in the gloom. “You did the right thing calling the police, then,” he said. “I am very strong.” This bravado evaporated as soon as Mbeya’s Central Police Station loomed into view.

The station was a squat, nondescript oblong surrounded by barracks, with a wide portico leading into a reception room bisected by a high counter. Police officers strutted in and out, each of them sporting the paunches that seem to go hand-in-glove with power in Tanzania. The lieutenant at the desk—a brutish, heavy-browed man in a bomber jacket—confiscated Mwizi’s personal belongings and another officer dragged him behind the scenes, “for processing,” they said. And then, through the doorway behind the counter, that horrifying scene: the table, the water pipe, the pants around the ankles, the pair of trembling legs sticking out of the green boxers, and the horrible realization that I put him there.

Looking up from his ledger, seeing my face crumple with dismay, the lieutenant at the front desk kicked the door closed with his heel. Ten seconds later, the screaming began.

“I just wanted my money back,” I gibbered.

What had I been expecting? I knew that the Tanzaniam police weren't about to win any prizes for their human-rights record. Deaths in custody are common here; extrajudicial killings are widely reported. Even as Mwizi’s shrieks rang through the building, there seemed to be no consistency in the way the police were dealing with the succession of desperate characters crossing their threshold. One man who came in beside a cowering woman, her eyes submerged by bruises that he had presumably just punched onto her face, seemed destined to escape with a reprimand.

Ten minutes later, Mwizi was dragged back into the vestibule looking forlorn and watery-eyed. It was immediately evident from his hobbled walk and hunched posture that they had beat him in the legs and stomach. I’d known that this was a possibility, but I’d been so blinded by rage that I hadn’t cared. Now, faced with the consequences, I wanted out.

He grimaced as he was forced back to the ground. “It was a mistake,” he whimpered, more for the benefit of his tormentors than for mine. Then, fixing my eye: “I have a family.” He cradled his wrists, which had been welted by the cuffs. His upper lip was trembling.

“You did it from your own free choice,” bellowed a policeman. “Why are you complaining about torture? You have to pay for your crime.” He turned away to castigate a bandy-legged woman who had just been dragged in.

Basic compassion demanded a change of tack. “I have no interest in seeing this man punished further,” I said, with false authority.

“Mzungu [a Bantu word for a person of European descent], we have already treated him,” spat a burly officer. “His relatives will be coming tomorrow morning with your money.”

Seeing me waver, Mwizi snatched his chance: “If they torture me like this again, it is better to die,” he said, before being dragged away again.

At nine the next morning, I was led through the bowels of the police station and into a dingy anteroom stacked high with yellowing case files. An obese female officer sat behind a desk in a creaking wooden chair. Mwizi was there—the picture of exhausted contrition. A deal was struck. Mwizi would have a month to gather the money he’d pilfered. His friends paid the necessary bribe, and we walked out, blinking into the sunshine, at 10 AM.

We did the obvious thing and went for a beer. Slurping greedily from a bottle of Nile Gold, Mwizi told me what they did to him in the room, how they hung him over the water pipe by his cuffs and smashed him about the legs and stomach with an iron bar. He’d spent the night in a lightless cell with 100 men stuffed inside it. “They kill people for less here,” he murmured pitifully.

I still felt a nagging urge to have it out with Mwizi, but by now my anger had all dried up. Here was this man with a wife and two boys seeing a weekly drip of pampered Westerners pass through his town with backpacks full of laptops, Kindles, and $750 cameras. The money he'd stolen from me—around $35—was pocket change to me, and I am by no means rich by Western standards. For him that cash meant food, shelter, and the survival of his family. In a country where everyone has to fight for himself, where corruption is rife and the police respond to a foreigner’s accusation with an iron bar, would I have been above doing the very same thing?

Three weeks later, as I disembark from the Abood bus from Morogoro, Mwizi is waiting at the door. He gives me a bear hug, and over a beer he tells me of his efforts to start making an honest living in the tourism sector, an industry to which he is apparently naturally predisposed. He admits that he has not obtained all of my money. I tell him that I am glad he has tried, and grateful for the 30,000 Tanzanian shillings (around $18) he has amassed in so short a time. I reiterate that I had never intended to have him so severely punished.

“If you hadn’t done that, I might have made the same mistake again,” he declared grandly. “God is very clever. I am thinking of you as a prophet. Now I want to change my life.”

That afternoon, back at the border, I step into the money changer and reach into my pocket for Mwizi’s hard-earned penitence. But my fingers find nothing—and then I remember the man on the minibus, who’d pressed rather too emphatically against my side to let a woman get off, and realize that the money has been pinched. I shake my head, suppress a moan, and shuffle off to get the fuck out of Tanzania.

![1916: 'PHYSICIST DAD' TURNS HIS ATTENTION TO GRAVITY, AND YOU WON'T BELIEVE WHAT HE FINDS. [PICS] [NSFW] 1916: 'PHYSICIST DAD' TURNS HIS ATTENTION TO GRAVITY, AND YOU WON'T BELIEVE WHAT HE FINDS. [PICS] [NSFW]](http://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/headlines.png)