By Gary Brecher

By Gary Brecher

On November 20, 2014

KUWAIT CITY — There are times when the sheer ignorance and ingratitude of the American public makes you sick.

KUWAIT CITY — There are times when the sheer ignorance and ingratitude of the American public makes you sick.

This week marks the 150th anniversary of Sherman’s March from Atlanta to the Sea, which set off on November 16, 1864—the most remarkable military campaign on the 19th century, the campaign which got Lincoln reelected, broke the back of the Confederacy, and slapped most of Dixie’s insane diehards into the realization they were defeated.

You’d think our newspaper of record, the New York Times, would find an appropriate way to mark the occasion, but the best the old Confederate-gray lady could come up with was a churlish, venomous little screed by an obscure neo-Confederate diehard named Phil Leigh. Leigh poses a stupid question: “Who Burned Atlanta?” and comes up with a stupider answer: “Sherman, that bad, bad man!”

Leigh actually thinks he’s fixing blame—blame!—for Sherman’s perfectly sensible, conventional action, the burning of a major rail center in his rear before setting out unsupported across enemy territory.

What next? Will the NYT dig up some crusty tenth-generation Tory sulking in the suburbs of Toronto to ask, “Who Killed All Those Innocent Redcoats on Bunker Hill?” Or a sob story by the Imperial Japanese Navy’s last surviving sailor asking, “Who Sank All Our Carriers?”

Leigh’s silly article could only work on totally ignorant readers, or on his fellow tenth-generation sulkers brooding about what went wrong circa 1863. And the funny side of that is that Sherman, more than anyone else in U.S. history, devoted his life to trying to slap these Dixie dreamers into waking up and thinking like grown-ups.

But it’s hopeless, as Leigh’s article reveals. Here’s Phil Leigh, a 21st century American, implicitly defending the old Southern delusion about a kindly, gentlemanly war:

“Perhaps the most widely accepted justification [for the burning of Atlanta] was the inherent cruelty of war. When a society accepts war as intrinsically cruel, those involved in wartime cruelties are exonerated.”

Phil Leigh seems to be the only human alive who doesn’t “…accept war as intrinsically cruel…”? All over the world, if you asked someone, “Is war intrinsically cruel, sir/madam?” they’d look at you like you were insane. But there does happen to be one demographic—an arguably insane one, indeed—which does not accept that war is cruel: the bitter white Southern neo-Confederate one to which Leigh belongs. For them, war was wonderful when it was just brave Southern gentlemen killing 360,000 loyal American soldiers.

That was the good war, as far as they were concerned. War became “intrinsically cruel” for them when that dastardly Sherman started visiting its consequences on rural Georgia, burning or destroying all supplies that could be used by the Confederate armies which had been slaughtering American troops for several years. Oh, that bad, bad Sherman!

Let’s settle Leigh’s little mind puzzle right off: Yeah, Leigh—you pus-filled sack of sore loser—you’re right, Atlanta was burned by William Tecumseh Sherman, the greatest general in American history. Damn right. That’s not a matter of blame, but of sound military sense.

What Southern romanticists like Leigh will never get—because it’s their very nature not to get it, just as a paranoid schizophrenic can never get that no one is persecuting him—is that Sherman’s whole military enterprise was an attempt to stop the slaughter by slapping the South into adulthood. From way before the war, when Sherman was a professor at a military academy in Louisiana, his attitude toward the South’s Planter culture was like a fond uncle watching his idiot nephew stumbling into a fast car, planning to drive drunk into the nearest tree.

Sherman tried to tell these idiots, over and over, that they were stupid and deluded. He wasn’t even going to debate the non-existent justice of their cause like Grant, who rightly called the Confederacy “the worst cause for which men ever fought.” Sherman, who was a much more analytical, intellectual man than Grant, focused on the fact that the South—the white, wealthy South, that is; the only one that mattered—was wrong. About everything. Every damn thing in the world. But most of all about its childishly romantic notions about war. Here’s what he said to his Southern friends before the war:

“You people of the South don’t know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don’t know what you’re talking about. War is a terrible thing! You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it … Besides, where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth — right at your doors. You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.”

That was Sherman’s advice to the South before the war even began. And he was, as usual, absolutely right. But he was talking like a grown-up to people who didn’t want to think like adults. Their whole society was based on horrible lies—“a bad cause to start with”—which gave them a deep aversion to cold truths. So they stuffed themselves, as Mark Twain said, with copious doses of the worst “chivalrous” nonsense they could find, like Walter Scott’s pseudo-medieval novels, and went off to cause the biggest slaughter of their fellow Americans in history, a body-count far higher than the sum total of all Americans killed in all wars with other countries.

Oh, but that was glorious, for idiots like Phil Leigh. What was non-glorious was Sherman burning Atlanta. You see what Sherman was up against? That’s why his campaigns, unlike any other Union general’s and in fact any other waged by an American commander until the age of “hearts and minds” warfare dawned a century later, were designed, above all, to smack awake a crazed and homicidally delusional population. Like John Wayne slapping some hysterical private, Sherman tried, in everything he said and did, to make the South face reality.

Sherman knew the wider world, and tried to warn the arrogant provincials who ran the Confederacy what it meant to them—all the peoples wiped out of existence for far less sustained craziness than the South was demonstrating, and all the eager immigrants waiting to take the traitors’ places:

“If [the Confederates] want eternal war, well and good; we accept the issue, and will dispossess them and put our friends in their place. I know thousands and millions of good people who at simple notice would come to North Alabama and accept the elegant houses and plantations there. If the people of Huntsville think different, let them persist in war three years longer, and then they will not be consulted. Three years ago by a little reflection and patience they could have had a hundred years of peace and prosperity, but they preferred war; very well. Last year they could have saved their slaves, but now it is too late.

All the powers of earth cannot restore to them their slaves, any more than their dead grandfathers. Next year their lands will be taken, for in war we can take them, and rightfully, too, and in another year they may beg in vain for their lives. A people who will persevere in war beyond a certain limit ought to know the consequences. Many, many peoples with less pertinacity have been wiped out of national existence.”

Sherman was trying, in everything he did, to wake these idiots from their delusion. That’s why they hate Sherman so much, 150 years after his campaign ended in total success: Because he interrupted their silly and sadistic dreams, humiliated them in the most vulnerable part of their weird anatomy, their sense of valorous superiority. Sherman didn’t wipe out the white South, though he could easily have done so; he was, in fact, very mild toward a treasonous population that regularly sniped at and ambushed his troops. But what he did was demonstrate the impotence of the South’s Planter males.

The taking and burning of Atlanta were just one more chance to slap the South awake, as Sherman saw it. When he was scolded—by people who were in the habit of whipping slaves half to death for trivial lapses—for his severity toward the (white, landowning) people of Atlanta, he replied, in his “Letter to Atlanta,” in a way that shows how patiently he kept trying to talk grown-up sense to an insane population:

“You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices to-day than any of you to secure peace. But you cannot have peace and a division of our country…

“The only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home, is to stop the war, which can only be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride.

“You have heretofore read public sentiment in your newspapers, that live by falsehood and excitement; and the quicker you seek for truth in other quarters, the better. I repeat then that, by the original compact of government, the United States had certain rights in Georgia, which have never been relinquished and never will be; that the South began the war by seizing forts, arsenals, mints, custom-houses, etc., etc., long before Mr. Lincoln was installed, and before the South had one jot or tittle of provocation. I myself have seen in Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi, hundreds and thousands of women and children fleeing from your armies and desperadoes, hungry and with bleeding feet…But these comparisons are idle. I want peace, and believe it can only be reached through union and war, and I will ever conduct war with a view to perfect an early success.”

Seems clear enough, right? “I just took your city, and out-thought as well as out-fought your generals and troops (and by the way, just to lay another fond Southern myth to rest, the Confederate troops who faced Sherman’s army were inferior, not just in numbers or equipment, but man-for-man, one-on-one, as they showed in dozens of battles)—so are you going to wake up and stop whistling Dixie, you loons?”

The answer was obvious: No, they weren’t. They still haven’t, as Phil Leigh’s nasty little commemoration of Sherman’s March demonstrates. You can’t fix crazy, and it seems to breed true down the generations.

Crazy people don’t need, or want, evidence. They prefer anecdotes with crying little girls. So here’s Phil Leigh’s case that burning Atlanta was a bad thing:

“One Michigan sergeant conceded getting swept up in the inflammatory madness, even though he knew it was unauthorized: ‘As I was about to fire one place a little girl about ten years old came to me and said, ‘Mr. Soldier you would not burn our house would you? If you did where would we live?’ She looked at me with such a pleading look that … I dropped the torch and walked away.”

Yes, one Michigan soldier, who was in a position to help slap the South awake by showing its impotence in the face of America’s vengeance, was overcome by sentimentality and “dropped the torch.” But that torch, as it were, was passed to stronger hands, and Atlanta burned. As it should have. You know what’s worse than a little girl asking “Mister Soldier” not to burn her house? Getting your leg sawed off by a drunken corpsman after a Minie ball fired by traitors turned your femur into bone shards. Or getting a letter that your son died of gangrene in one of those field hospitals where the screaming never stopped, and the stench endured weeks after the army had moved on. Those are the realities of war that Sherman hated—truly hated, which is something you can’t say by any means about most successful generals—and tried to bring to a quick end.

Sherman never forgot those horrors. I repeat, he was one of a very few great generals I know who genuinely hated war, and he never lost a chance to say so:

“I confess, without shame, that I am sick and tired of fighting — its glory is all moonshine; even success the most brilliant is over dead and mangled bodies, with the anguish and lamentations of distant families, appealing to me for sons, husbands, and fathers … it is only those who have never heard a shot, never heard the shriek and groans of the wounded and lacerated … that cry aloud for more blood, more vengeance, more desolation.”

Sherman never stopped talking like this, even after the war, when memories dimmed and a sentimental nostalgia became the norm among aging Union veterans. Most people know that Sherman said, “War is Hell,” but few know that he said it in a context where it took real courage, where he was raining on a bunch of young military graduates’ parades. That quote comes from an address Sherman made at a graduation ceremony for the Michigan Military Academy (as long as we’re gonna talk about “Mister Soldier” from Michigan!) and he told those guys flat-out they’d picked the wrong major:

“I’ve been where you are now and I know just how you feel. It’s entirely natural that there should beat in the breast of every one of you a hope and desire that some day you can use the skill you have acquired here. Suppress it! You don’t know the horrible aspects of war. I’ve been through two wars and I know. I’ve seen cities and homes in ashes. I’ve seen thousands of men lying on the ground, their dead faces looking up at the skies. I tell you, war is Hell!”

Here again we see Sherman in his true glory, a cold, bright mind in a world of bloody, hypocritical, murderous sentimental Victorian swine. I only truly love two Civil War commanders, Sherman and George Thomas, the best of all. But Thomas was a softer man than Sherman, too tender by half to see what Sherman saw. Sherman saw the horror full-on, and never flinched.

But that horror just doesn’t register with the Phil Leighs of the world. As far as they’re concerned, it was glorious to kill 300,000 loyal American soldiers in defense of the most vile social system since Sparta. (And by the way, it’s no wonder that rotten movie 300 was so popular in Leigh’s demographic, because the parallels between fuckin’ Sparta and the friggin’ Confederacy are as numerous and disgusting as the roaches in my Kuwait City apartment.)

As far as the Times’ resident neo-Confederate’s concerned, the war was going swimmingly until Sherman came along and bummed their high by abandoning their ersatz chivalry and showing the Planters’ sons their total impotence by marching through their heartland, burning and looting as they pleased.

Sherman, as usual, saw clearly that the craziness of the white South was bone-deep, and could never fully be eradicated. He wouldn’t have been surprised to read Phil Leigh’s spitball-commemoration of his Atlanta victory. What Sherman did hope—and it was a realistic hope, fulfilled by history—was to suppress the South’s craziness for a few generations:

“We can make war so terrible and make [the South] so sick of war that generations pass away before they again appeal to it.”

And it worked; it wasn’t until the past decade or so that these neo-Confederate vermin dared to raise their heads and start hissing their crazy nonsense in public. So Sherman’s alleged brutality, you see, Mister Leigh, was not a matter of blame, or a regrettable side-effect of his campaign. It was the point of his campaign. Sherman began with the goal of humiliating a Southern white elite consumed by delusions of superiority, and the plumes of smoke his bummers sent up as they burned the mansions in their sixty-mile wide swath were meant as a form of advertising: “See? See what we can do if we want to? Now will you fucking wake up?”

Sherman burned Atlanta for two reasons, both perfectly sound:

- Because no sane general, planning to send an army of more than 60,000 men across the enemy’s heartland with no supply line or hope of reinforcement, would leave a major rail/supply center like Atlanta intact in his rear. Burning Atlanta was a no-brainer. Any commander would have done the same, but very few would have dared undertake the march from Atlanta to the Sea at all. It was so radical a plan that British military historian B. H. Liddell Hart claimed it marked Sherman as “the first modern general” and placed him alongside Napoleon and Belisarius as one of the greatest commanders of all time.

- Because every column of smoke rising from a burning mansion, barn, or granary was intended by Sherman as a signal to a psychotically stubborn, deluded Confederate (white, landowning) population that they had lost, and that every additional life lost was, as he kept trying to tell them, an atrocity, a crime far greater than property destruction.

Sherman never admitted to ordering the burning of Atlanta, because—let’s be honest here—there are two rules for American wars: What we do to foreigners, and what we do to other Americans—and for some reason, most historians persist in considering the slave-selling traitors, America-hating swine who ran the Confederacy as Americans. So we could never treat them as we did the people of, say, Tokyo or Dresden, even though the people of those two cities were never responsible for killing so many Americans as the Confederates did.

So Sherman said only this about the burning:

“Though I never ordered it, and never wished for it, I have never shed any tears over the event, because I believe that it hastened what we all fought for, the end of the war.”

He, unlike the Phil Leighs of the world, was thinking about all the horrors of endless guerrilla war: “If the United States submits to a division now, it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is eternal war…” — which terrified sane grown-ups both North and South, including Robert E. Lee, who told his aides that it was the horror of guerrilla war that made him accept the humiliation of surrender. When the very young, excitable General Porter Alexander proposed that the Army of Northern Virginia literally head for the hills and try guerrilla warfare, Lee answered like a real grown-up:

“You and I…must consider its effect on the country [i.e. the Confederacy] as a whole. Already it is demoralized by the four years of war. If I took your advice, the men would be without rations and under no control of officers. They would be compelled to rob and steal in order to live. They would become mere bands of marauders, and the enemy’s cavalry would pursue them and overrun many sections they may never have occasion to visit. We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from. And, as for myself, you young fellows might go bushwhacking, but the only dignified course for me would be to go to General Grant and surrender myself and take the consequences of my acts.”

Lee wasn’t as sensible as he could have been because any sane Southern officer knew very well that after the twin defeats at Vicksburg and Gettysburg, the lousy grand old cause was lost and all deaths from now on were completely in vain. But at least he knew that guerrilla war usually inflicts ten casualties on the occupied, i.e. the South, for every one inflicted on the occupier, i.e. the Union troops. But then Lee had moments of lucidity in an otherwise chivalry-warped consciousness; the Phil Leighs among us have none.

Sherman was, by contrast, the most grimly sane American ever born—and compared to the endless, mindless brutality of guerrilla war—a Jesse & Frank James world, a Quantrill world, metastasized across the continent, compared to which burning a few houses was a wholesome purgative.

Of course, this is all lost on the Phil Leighs of the world, who—for reasons that cut deep into the ideology of the American right wing—always take burnt houses too seriously, and dead people far too lightly. To them, burning a house is a crime, while shooting a Yankee soldier in the eye is just part of war’s rich tapestry. So their horror of messing with private property joins their sense of emasculation, and their total ignorance of what war on one’s home ground actually means, to form a sediment that could never have been cured, even temporarily, except by the river of armed humanity Sherman sent pouring south and east from Atlanta on November 15, 1864. That cold shower woke them for a little while, at least—long enough to quicken the end of the war and save thousands of lives.

That was all Sherman hoped for. He’d spent time with these guys, and knew they could never really be cured:

“…Sons of [Southern] planters, lawyers about towns, good billiard players and sportsmen, men who never did any work and never will. War suits them …”

Well, they’ve gained about 60 pounds per capita and forgotten how to ride a horse, but they’re still around, still sulking, and, thanks to the New York Times, they’ve been able to let the rest of us know it. After all, what good is a 150-year sulk if nobody notices it?

[Illustration: Brad Jonas for Pando]

Gary Brecher is the War Nerd.

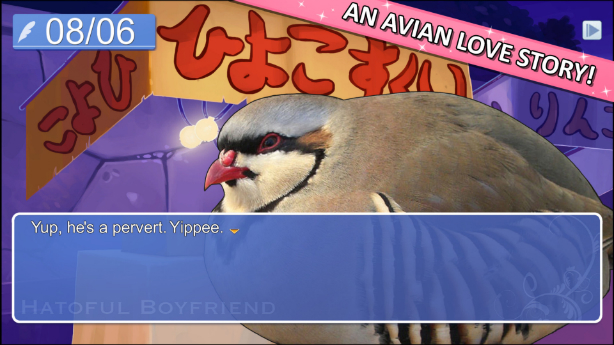

Finally, you can go to the park and feed the pigeons while simultaneously dating a handful of pigeons and discovering their bird-brained plot to overtake the world and enslave humanity. Finally.

Pigeon-dating simulator Hatoful Boyfriend is due out o...

Finally, you can go to the park and feed the pigeons while simultaneously dating a handful of pigeons and discovering their bird-brained plot to overtake the world and enslave humanity. Finally.

Pigeon-dating simulator Hatoful Boyfriend is due out o...

By

By  KUWAIT CITY — There are times when the sheer ignorance and ingratitude of the American public makes you sick.

KUWAIT CITY — There are times when the sheer ignorance and ingratitude of the American public makes you sick.

facebook

facebook reddit

reddit