[Content warning: Severe mistreatment of the mentally ill. Through this post, I’ll be following Foucault in using the politically incorrect term “madness” rather than the more modern “mental illness”, because a big part of his point is worrying about the assumptions contained in the latter term.]

I.

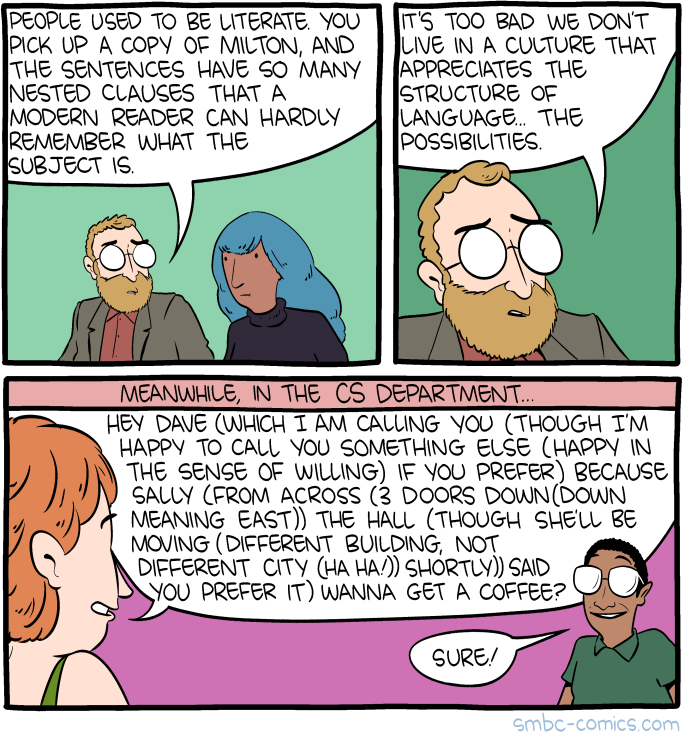

I started reading Foucault’s Madness And Civilization with the expectation that it would be tedious and incomprehensible. You know, the stereotype that postmodernism / post-structuralism / Continentalism / etc. involves a lot of negation of the negation of the inversion of the Other within the Absolute within [and so on for 200 pages]. There was a little of that. But there was also a fascinating look at the history of mental illness, an entertainingly bombastic writing style, and a few ideas that I might have actually half-understood.

The book asked: how have we historically drawn the category boundaries around madness? If there is some great continent containing nations like Irrationality, Immorality, Illness, and Inspiration, from which of these countries have cartographers carved out a homeland for Madness? What wars have been fought over which provinces? What propaganda supports the current international order. And how accurate is it?

II.

Foucault starts with the Late Middle Ages / early Renaissance, when there was suddenly an explosion of interest in madness. The most famous works from this tradition are Ship of Fools and In Praise Of Folly (“fool” originally meant “insane person”) – not to mention pretty much everything by Hieronymus Bosch – and of course Foucault has intensely studied two hundred other examples I’ve never heard of. His theory is that this shares a source with the late medieval fascination with death (think all of those pictures of dancing skeletons). In both cases, the stable tidy medieval order is teetering towards collapse, and so the popular imagination is seized by images of the Outside invading the familiar world.

I feel bad juxtaposing so eminent a figure as Foucault with Lovecraft, but I found his description of Renaissance madness easiest to understand as basically Lovecraftian. We’ve somehow lucked into a bubble of comfortable stability within a vast and horrifying universe. We’ve become so complacent that we’ve forgotten about the bubble and are starting to poke around the edges. When bits of the Outside leak in, madness is the inevitable result. Lovecraft came of age during the First World War, as a European order that considered itself too enlightened to die went down in flames. The end of the Middle Ages must have been a similar period. The insane are those who have seen too much of the horrors that lurk beyond the veil – Yog-Sothoth, Protestantism, whatever.

And like Cthulhu, madness has an affinity for water:

One thing at least is certain: water and madness have long been linked in the dreams of European man. Already, disguised as a madman, Tristan had ordered boatmen to land him on the coast of Cornwall…And more than once in the course of time, the same theme reappears: among the mystics of the fifteenth century, it has become the motif of the soul as a skiff, abandoned on the infinite sea of desires, in the sterile field of cares and ignorance, among the mirages of knowledge, amid the unreason of the world — a craft at the mercy of the sea’s great madness, unless it throws out a solid anchor, faith, or raises its spiritual sails so that the breath of God may bring it to port. At the end of the sixteenth century, De Lancre sees in the sea the origin of the demoniacal leanings of an entire people: the hazardous labor of ships, dependence on the stars, hereditary secrets, estrangement from women—the very image of the great, turbulent plain itself makes man lose faith in God and all his attachment to his home; he is then in the hands of the Devil, in the sea of Satan’s ruses.

And so, Foucault tells us, in the fifteenth century there is a sudden emergence of a complex of artistic and philosophical themes linking madmen, the sea, and the terrible mysteries of the world. These culminate in the Ship Of Fools:

Renaissance men developed a delightful, yet horrible way of dealing with their mad denizens: they were put on a ship and entrusted to mariners because folly, water, and sea, as everyone then knew, had an affinity for each other. Thus, “Ships of Fools” crisscrossed the seas and canals of Europe with their comic and pathetic cargo of souls. Some of them found pleasure and even a cure in the changing surroundings, in the isolation of being cast off, while others withdrew further, became worse, or died alone and away from their families. The cities and villages which had thus rid themselves of their crazed and crazy, could now take pleasure in watching the exciting sideshow when a ship full of foreign lunatics would dock at their harbors.

This was such a great piece of historical trivia that I was shocked I’d never heard it before. Some quick research revealed the reason: it is completely, 100% false. Apparently Foucault looked at an allegorical painting by Hieronymus Bosch, decided it definitely existed in real life, and concocted the rest from his imagination.

Foucault apologists try to rescue this, say that he was just being poetic in some way. He wasn’t. Page 8 in my copy: “Of all these romantic or satiric vessels, the Narrenschiff [Ship Of Fools] is the only one that had a real existence — for they did exist, these boats that conveyed their insane cargo from town to town.” He really, really doubled down on this point. As far as I can tell, this is just as bad a failing of scholarship as it sounds – and surprising, since everything else about the book gives the impression of Foucault as an incredibly knowledgeable and wide-ranging scholar.

I couldn’t find any mention of equally bad flaws in the rest of the book, and Foucault really does seem to know his stuff, so I’m tempted to treat this as a one-off error, albeit a completely inexplicable one. I’m including it anyway as a warning before getting into some other pretty weird stuff.

III.

Eventually the Renaissance became less of an impending threat and more of a fait accompli, and people’s worries died down a bit. Madness began to be treated more as ordinary immorality. This didn’t necessarily mean people freely chose to be mad – the classical age didn’t think in exactly the same “it’s your fault” vs. “it’s biological” terms we do – but it was considered due to a weakness of character in the same way as other failures.

In some cases, it was the result of an excess of passions, flightiness, or imagination: the most famous example is Don Quixote, who went crazy after reading too many fiction books. This was actually considered a very serious risk by practically all classical authorities, especially for women. Foucault quotes Edme-Pierre Beauchesne:

In the earliest epochs of French gallantry and manners, the less perfected minds of women were content with facts and events as marvelous as they were unbelievable; now they demand believable facts yet sentiments so marvelous that their own minds are disturbed and confounded by them; they then seek, in all that surrounds them, to realize the marvels by which they are enchanted; but everything seems to them without sentiment and without life, because they are trying to find what does not exist in nature.

And a newspaper of the time:

The existence of so many authors has produced a host of readers, and continued reading generates every nervous complaint; perhaps of all the causes that have harmed women’s health, the principal one has been the infinite multiplication of novels in the last hundred years … a girl who at ten reads instead of running will, at twenty, be a woman with the vapors and not a good nurse.

Novels weren’t the only danger, of course. There were other hazards to watch for, like waking up too late:

The moment at which our women rise in Paris is far removed from that which nature has indicated; the best hours of the day have slipped away; the purest air has disappeared; no one has benefited from it. The vapors, the harmful exhalations, attracted by the sun’s heat, are already rising in the atmosphere.

Also, freedom:

For a long time, certain forms of melancholia were considered specifically English; this was a fact in medicine and a constant in literature…Spurzheim made a synthesis of all these analyses in one of the last texts devoted to them. Madness, “more frequent in England than anywhere else,” is merely the penalty of the liberty that reigns there, and of the wealth universally enjoyed. Freedom of conscience entails more dangers than authority and despotism. “Religious sentiments exist without restriction; every individual is entitled to preach to anyone who will listen to him”, and by listening to such different opinions, “minds are disturbed in the search for truth.”

These are a very selective sampling of quotes from just one of Foucault’s many chapters, and some of them are separated by centuries from others, but the overall impression I got was that conformity/wholesomeness/clean living was salubrious, and deviations from these likely to cause madness. Essentially, if you deviate from your humanity a little bit of the way – by failing to be a godly, sober-living, and industrious person – then that can compound on itself and make you lose practically all of your humanity. You will end up a feral madman, little different from a beast.

This naturally lumped madness in together with the other failures of industry and godliness: crime and poverty. During the seventeenth century, madmen, beggars, and criminals were all crammed together in workhouses. These were always sort of ambiguous between “maybe the structure and routine of work will help these poor souls find the right path” and “let’s keep these losers away from the rest of us”. The opening of the workhouses was sudden and dramatic: in Paris, it began Monday May 14, 1657, when “the archers began to hunt down beggars and herd them into the different buildings of the Hospital.” In England, it started around 1630, when the King recommended prosecuting:

…all those who live in idleness and will not work for reasonable wages, or who spend what they have in taverns…for these people live like savages without being married, nor buried, nor baptized; and it is this licentious liberty which causes so many to rejoice in vagabondage.

Foucault stresses that this wasn’t some plot on the part of authorities to enslave beggars and profit off their labor. The people in charge of the workhouses generally failed at assigning work that was profitable or productive, even in the weak sense of productive at lining their own pockets. They seemed genuinely driven by a belief in the curative power of Honest Work:

Measured by their functional value alone, the creation of the houses of confinement can be regarded as a failure. Their disappearance throughout Europe, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, as receiving centers for the indigent and prisons of poverty, was to sanction their ultimate failure: a transitory and ineffectual remedy, a social precaution clumsily formulated by a nascent industrialization. And yet, in this very failure, the classical period conducted an irreducible experiment. What appears to us today as a clumsy dialectic of production and prices then possessed its real meaning as a certain ethical consciousness of labor, in which the difficulties of the economic mechanisms lost their urgency in favor of an affirmation of value.

In this first phase of the industrial world, labor did not seem linked to the problems it was to provoke; it was regarded, on the contrary, as a general solution, an infallible panacea, a remedy to all forms of poverty. Labor and poverty were located in a simple opposition, in inverse proportion to each other. As for that power, its special characteristic, of abolishing poverty, labor – according to the classical interpretation — possessed it not so much by its productive capacity as by a certain force of moral enchantment. Labor’s effectiveness was acknowledged because it was based on an ethical transcendence. Since the Fall, man had accepted labor as a penance and for its power to work redemption. It was not a law of nature which forced man to work, but the effect of a curse. The earth was innocent of that sterility in which it would slumber if men remained idle: “The land had not sinned, and if it is accursed, it is by the labor of the fallen man who cultivates it; from it no fruit is won, particularly the most necessary fruit, save by force and continual labor.”

According to Johan Huizinga, there was a time, at the dawn of the Renaissance, when the supreme sin assumed the aspect of Avarice, Dante’s cièca cupidigia. The seventeenth-century texts, on the contrary, announced the infernal triumph of Sloth: it was sloth which led the round of the vices and swept them on. Let us not forget that according to the edict of its creation, the Hôpital Général must prevent “mendicancy and idleness as sources of all disorder.” Louis Bourdaloue echoes these condemnations of sloth, the wretched pride of fallen man; “What, then, is the disorder of an idle life? It is, replies Saint Ambrose, in its true meaning a second rebellion of the creature against God.” Labor in the houses of confinement thus assumed its ethical meaning: since sloth had become the absolute form of rebellion, the idle would be forced to work, in the endless leisure of a labor without utility or profit.

Foucault presents confinement alternately as workhouses mixing together madmen and poor people, and as ultra-secure special hospitals for the insane. I’m not sure what to make of this contradiction; maybe the less ill people were in one, and the more ill people in the other? Maybe he’s just interested in the general phenomenon of confinement? In any case, the places for the insane were pretty bad too:

In his Report on the Care of the Insane Desportes describes the cells of Bicetre as they were at the end of the eighteenth century: “The unfortunate whose entire furniture consisted of this straw pallet, lying with his head, feet, and body pressed against the wall, could not enjoy sleep without being soaked by the water that trickled from that mass of stone.” As for the cells of La Salpêtrière, what made “the place more miserable and often more fatal, was that in winter, when the waters of the Seine rose, those cells situated at the level of the sewers became not only more unhealthy, but worse still, a refuge for a swarm of huge rats, which during the night attacked the unfortunates confined there and bit them wherever they could reach them; madwomen have been found with feet, hands, and faces torn by bites which are often dangerous and from which several have died.”

It would be nice to think these kinds of things only survived because the public didn’t know about them, but that, uh, doesn’t seem to be quite what was happening:

As late as 1815, if a report presented in the House of Commons is to be believed, the hospital of Bethlehem exhibited lunatics for a penny, every Sunday. Now the annual revenue from these exhibitions amounted to almost four hundred pounds, which suggests the astonishingly high number of 96,000 visits a year.

All of these locks and chains and cages and exhibitions draw an obvious analogy of madmen and animals. Foucault doesn’t think this is a coincidence:

When practices reach this degree of violent intensity, it becomes clear that they are no longer inspired by the desire to punish nor by the duty to correct. The notion of a “résipiscence” is entirely foreign to this regime. But there was a certain image of animality that haunted the hospitals of the period. Madness borrowed its face from the mask of the beast. Those chained to the cell walls were no longer men whose minds had wandered, but beasts preyed upon by a natural frenzy: as if madness, at its extreme point, freed from that moral unreason in which its most attenuated forms are enclosed, managed to rejoin, by a paroxysm of strength, the immediate violence of animality. This model of animality prevailed in the asylums and gave them their cagelike aspect, their look of the menagerie…

What is most important is that it is conceived in terms of an animal freedom. The negative fact that “the madman is not treated like a human being” has a very positive content: this inhuman indifférence actually has an obsessional value: it is rooted in the old fears which since antiquity, and especially since the Middle Ages, have given the animal world its familiar strangeness, its menacing marvels, its entire weight of dumb anxiety. Yet this animal fear which accompanies, with all its imaginary landscape, the perception of madness, no longer has the same meaning it had two or three centuries earlier: animal metamorphosis is no longer the visible sign of infernal powers, nor the result of a diabolic alchemy of unreason. The animal in man no longer has any value as the sign of a Beyond; it has become his madness, without relation to anything but itself: his madness in the state of nature. The animality that rages in madness dispossesses man of what is specifically human in him; not in order to deliver him over to other powers, but simply to establish him at the zero degree of his own nature.

There is a lot I didn’t understand about this section, but the overall gist seems to be trying to lump the insane in together with other forms of badness and deviation from the moral norm – whether animals or criminals – and shutting them away where they could not be seen.

IV.

The late eighteenth century on was the period of reform, when the mentally ill were taken out of the prisons and workhouses and brought to nice benevolent asylums in the countryside where they could convalesce in peace under the supervision of expert doctors.

…or at least this is the prevailing narrative. Foucault is having none of it.

The houses of confinement weren’t just for criminals and madmen. They were also for the “undeserving poor” – homeless, beggars, unemployed. But the Industrial Revolution was changing the conception of poverty. Foucault places this in the context of modern economics, which introduced abstract ideas like “jobs” and “workers”. In this model, the poor were potential workers who just lacked jobs, not the weird exotic subspecies of humanity called “paupers”. The past paradigm had focused on healing their souls through the redemptive power of make-work; the new paradigm said that if they could be enlisted to work productive industrial jobs it would improve the Economy and everyone would be better off.

Out they went, and now instead of just being an undifferentiated mass of undesirables, the hospitals were more obviously just the two disparate populations of criminals and madmen. But surely now is the point where people see how inhumane it is to stick the mentally ill together with criminals, right?

Sort of.

When the Prior of Senlis asked that madmen be separated from certain convicts, what were his arguments? “He is deserving of mercy, as well as two or three others who would be better off in some citadel, because of the company of six others who are mad, and who torment them night and day.” And the meaning of this sentence would be so clearly understood by the police that the internees in question would be set free. And the demands of the Brunswick overseer have the same meaning: the workshop is disturbed by the cries and the confusion of the insane; their frenzy is a perpetual danger, and it would be better to send them back to the cells, or to keep them in chains. And already, we can anticipate that from one century to the next, the same protests did not have, at bottom, the same value. Early in the nineteenth century, there was indignation that the mad were not treated any better than those condemned by common law or than State prisoners; throughout the eighteenth century, emphasis was placed on the fact that the prisoners deserved a better fate than one that lumped them with the insane […]

La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt bears witness to this in his report to the Committee on Mendicity: “One of the punishments inflicted upon the epileptics and upon the other patients of the wards, even upon the deserving poor, is to place them among the mad.” The scandal lies only in the fact that the madmen are the brutal truth of confinement, the passive instrument of all that is worst about it.

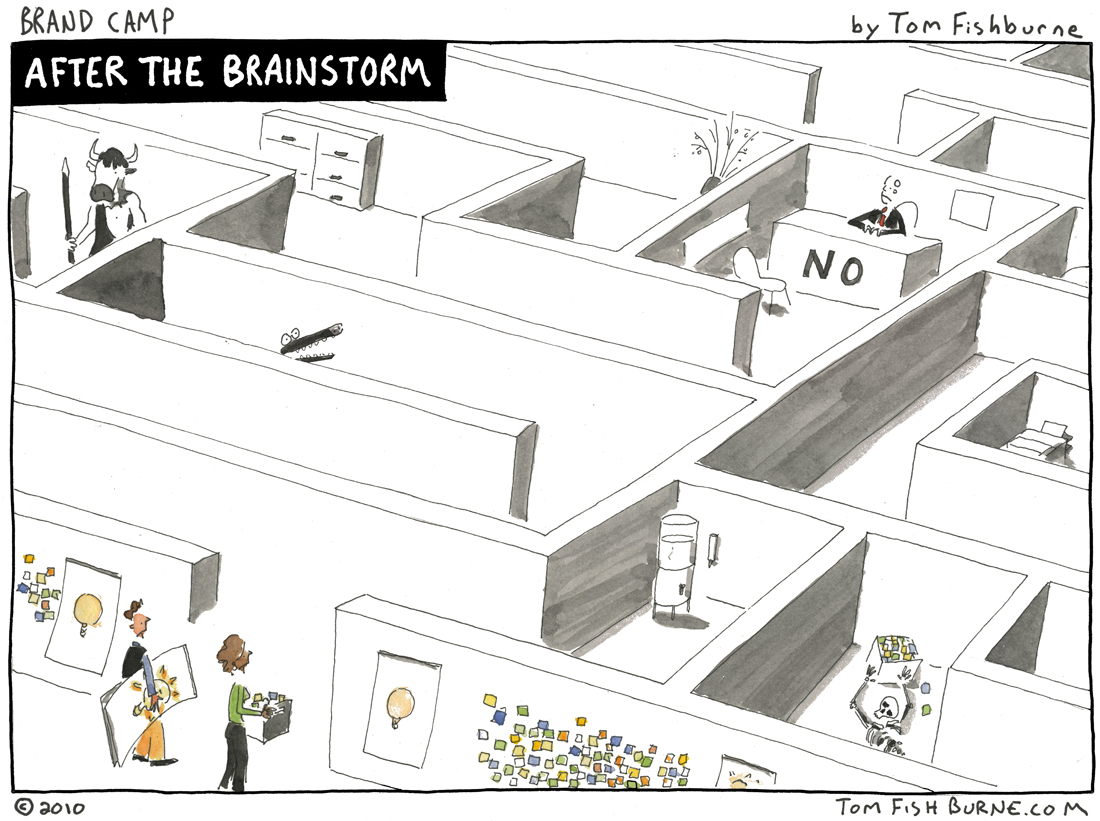

There was apparently general agreement that it was unfair to criminals to keep them confined together with madmen, so out went the criminals – with the madmen staying around in institutions that were starting to sort of resemble the idea of a modern psychiatric hospital.

The beginning of the nineteenth century did start to see fewer chains and rats, and more attempt to treat madmen as human beings. But Foucault is perversely annoyed by this, convinced that this was secretly a way of respecting the mentally ill even less. He notes that their newfound rights were conditional on good behavior and on acting sane, and so in a sense these new more compassionate hospitals gave them less freedom than the old ball-and-chain deal. In the older hospitals, you could do whatever you wanted. You’d be doing it on the wrong side of iron bars, mocked by people who hated you, but you could do it. In the new hospitals, you were forced to constantly perform and please your guards and nurses in order to maintain your privileges. Madmen went from being treated like criminals – who at least are still adult citizens – to being treated like children:

We must therefore re-evaluate the meanings assigned to Tuke’s work: liberation of the insane, abolition of constraint, constitution of a human milieu – these are only justifications. The real operations were different. In fact Tuke created an asylum where he substituted for the free terror of madness the stifling anguish of responsibility; fear no longer reigned on the other side of the prison gates, it now raged under the seals of conscience. Tuke now transferred the age-old terrors in which the insane had been trapped to the very heart of madness. The asylum no longer punished the madman’s guilt, it is true; but it did more, it organized that guilt; it organized it for the madman as a consciousness of himself, and as a non-reciprocal relation to the keeper; it organized it for the man of reason as an awareness of the Other, a therapeutic [and so on for two hundred pages].

A lynchpin of this system was doctors. Foucault says that at this time, doctors really didn’t make much pretense to being able to cure mental illness. Their main role was as a representative of polite society and healthy living. The doctor would go in, talk to some mad people about how really being virtuous and healthful was better than being degenerate and crazy, and this would help the process of drawing them back into the social order (and so out of the excessive wild liberty that was madness). The more high-status and authoritative the doctor, the better – and he has lots of examples of doctors supposedly curing madmen with a couple of stern words delivered in a suitably censorious tone.

He theorizes that after the restore-to-social-order idea of mental health became obsolete, doctors were stuck without a purpose. That is, it was known that it was important to have doctors treating the mentally ill, but unclear exactly what they were supposed to do. One response was to flounder around for a while on various scams and miracle cures. Another response was Freud’s: to accept that the doctor-patient relationship itself somehow had magical properties, and that the doctor being a silent authority figure sitting in judgment of you was actually an effective way to cure psychiatric disease.

V.

Everything above is a really superficial reading of Madness And Civilization and probably misses the whole point of the book.

This point is something that alternately seems postmodern or kabbalistic or – for lack of a better term – insane. It’s not just saying that This Historical Period treated the mad This Way, but That Historical Period treated them That Way. It’s trying to peek beneath the hood (or the veil?) to find the zeitgeist, the animating spirit of the European continent that led them to do things as they did and which transformed one schema into another. This is rarely anything sensible, like “the economy improved” or “there was a revolution”. More often it’s some kind of deep subconscious beliefs about the meaning of humanity or freedom or symbolism or something. If Europe was one guy, this book would be Foucault performing Freudian dream analysis on that guy.

For example, the Europeans didn’t put their madmen on Ships Of Fools just because it was a convenient way to get rid of them, but also because:

Water adds to this the dark mass of its own values; it carries off, but it does more: it purifies. Navigation delivers man to the uncertainty of fate; on water, each of us is in the hands of his own destiny; every embarkation is, potentially, the last. It is for the other world that the madman sets sail in his fools’ boat; it is from the other world that he comes when he disembarks. The madman’s voyage is at once a rigorous division and an absolute Passage. In one sense, it simply develops, across a half-real, half-imaginary geography, the madman’s liminal position on the horizon of medieval concern—a position symbolized and made real at the same time by the madman’s privilege of being confined within the city gates: his exclusion must enclose him; if he cannot and must not have another prison than the threshold itself, he is kept at the point of passage. He is put in the interior of the exterior, and inversely. A highly symbolic position, which will doubtless remain his until our own day, if we are willing to admit that what was formerly a visible fortress of order has now become the castle of our conscience.

Confined on the ship, from which there is no escape, the madman is delivered to the river with its thousand arms, the sea with its thousand roads, to that great uncertainty external to everything. He is a prisoner in the midst of what is the freest, the openest of routes: bound fast at the infinite crossroads. He is the Passenger par excellence; that is, the prisoner of the passage. And the land he will come to is unknown—as is, once he disembarks, the land from which he comes. He has his truth and his homeland only in that fruitless expanse between two countries that cannot belong to him. Is it this ritual and these values which are at the origin of the long imaginary relationship that can be traced through the whole of Western culture? Or is it, conversely, this relationship that, from time immemorial, has called into being and established the rite of embarkation?

Let’s appreciate a few things about this passage. First, it’s phenomenal writing. I apologize for thinking all Continental philosophy had to be badly-written; in retrospect Nietzsche should have cured me of this delusion.

But second, it’s totally bonkers. Like, forget the fact that there weren’t any real Ships Of Fools and Foucault is analyzing a literary motif. Forget that the literary motif actually comes from a metaphor by Plato which is about something else. Even if the rivers of Europe were choked with such Ships, this is just a phenomenally unproductive way to think about anything. This is the kind of thought process where we drill for oil because we are symbolically sexually penetrating Mother Earth (insert kabbalistic analysis of the word “fracking” here).

There is a lot along these lines, none of which I am really able to follow, especially because the book never gives a clear definition of its crucial term “unreason”. The closest I can come is a theory that the Renaissance (and to some degree the later classical period) thought of madness as potentially interesting and valuable. They didn’t like madmen, but they occasionally tried to have a “dialogue between madness and reason”, where they would try to understand where the mad were coming from and what they had to offer civilization. In later periods, this was lost, and the mad were just confined away from human sight – but there was still at least some dignity in it, because madness was allowed to exist on its own terms. Later, when bleak prison workhouses transitioned to humane medical asylums, even that dignity was lost, as sane people’s imperative changed to forcing the mad to conform to the sane world’s standards and deny their madness’ existence.

This is the thrust of the last chapter, and Foucault ties all of this together into a case that all of the reformers were just jerks, and they sought more humane treatment for the mentally ill out of a desire to judge and dominate them. This is fantastically contrarian. Foucault does not give an inch to the position that maybe there was something good and wholesome about the desire to rescue people from being crammed by the dozen in rat-infested cells with all of their limbs chained together. He doesn’t specifically say the rat-infested cells were better, but he sure hints at it pretty hard.

I always like contrarian takes. But I can’t make sense of what Foucault is trying to do here. And also, some of the same sites that debunk the Ship Of Fools thing say that actually the Renaissance was super-cruel to mad people, and Foucault’s picture of them as tolerant and understanding is composed entirely of cherry-picking and imagination.

The best I can do here is say that Foucault is too much of an Idealist where I am a Materialist. I measure humanitarian victories in prisoners freed and rat bites averted. He seems to measures them how the dream sequences of Personified Europe are treating the dialogue between Madness and Reason. Probably there’s a perspective in which this makes sense, but this book didn’t manage to teach me to appreciate it.

VI.

Granted that I couldn’t appreciate the philosophy and remain doubtful of the scholarship, I still enjoyed this book. It was a weird tour of parts of history I wouldn’t otherwise have thought of. And it did accomplish the post-modernist goal of broadening my perspective enough to be more doubtful of my own society’s institutions.

The idea of novel-reading causing insanity seems ridiculous to us. But is it any more ridiculous than the idea of video games causing violence? Or stereotype threat causing poor test performance? The dustbin of scientific history is filled with weird claims that various social and cultural phenomena have powerful effects on the mind, from refrigerator-mother schizophrenia to low self-esteem causing crime. Surely this is one more warning to before voodoo psychology.

But that’s too easy. I also worry about the idea – constant in its essence in every time period, though changing in its particulars – that mental illness is the result of living your life in an unwholesome way and indulging in illicit pleasures. In the classical period, this included everything from waking up too late, to not working long enough hours, to getting too romantically infatuated, to, well…

Heat clears the way for liquids. It is precisely for this reason that all the hot drinks the seventeenth century used and abused risk becoming harmful: relaxation, general humidity, softness of the entire organism. And since these are the distinctive traits of the female body, as opposed to virile dryness and solidity, the abuse of hot drinks risks leading to a general feminization of the human race. [Thomas Sydenham warns:] “Most men are censured, not without reason, for having degenerated in contracting the softness, the habits, and the inclinations of women. Excessive use of humectants immediately accelerates the metamorphosis and makes the two sexes almost as alike in the physical as in the moral realm. Woe to the human race, if this prejudice extends its reign to the common people.”

And I can’t help noticing a resemblance between this and the modern insistence on diet and exercise. They’ve got the same kind of element of “if you don’t exert a lot of willpower to live your life in a diligent way, then you shouldn’t be surprised when you end up mentally ill.” Although the role of poor diet/exercise in physical illness is beyond questioning, its role in mental illness is more anecdotal and harder to pin down. Don’t get me wrong, there are lots of studies showing it works. But there’s also lots of anomalous data, like how exercise performed as part of your job doesn’t help. This has led some people to suggest that the physical effects of exercise are less important than the social role – the feeling of doing something to fight your depression and conform to a virtuous mode of life. Exercise works for that – but so might avoiding novels and staying away from hot drinks, if that was what your society wanted. I’m not saying this is definitely true. I’m just saying I give it higher credence now that the pattern of “people always want to use willpower-induced conformity to social order as a bulwark against mental illness” is more apparent.

On the other hand, it’s also important not to dismiss something we believe today just because people in the past believed the same thing. I was tempted to say something like I’m skeptical of modern-day behavioral activation because it sounds exactly like past-days “work will cure you because idleness is the mother of all sins” doctrine. But on closer examination, I’m using evidence wrong here. If people in the past believed something, that should be at least some positive evidence it was true – or at least not negative evidence. Of course, they’re going to phrase it in really awkward politically-incorrect ridiculous-seeming terms, because they’re the past. And they’ll probably figure out some way to make it imply a moral atrocity, because, again, past. But that doesn’t mean they’re wrong. Very possibly it’s a timeless truth that routine and purposeful activity help depression. The past phrased this as “idleness is the mother of sin so we should force everyone into workhouses”, and now we’re not as much about forced labor and tracing out sin’s family tree. But behavioral activation therapy still seems pretty powerful.

I think I am going to be suspicious when the implied message stays the same but the specifics keep changing – “stay away from exciting novels” vs. “stay away from violent video games”, or “avoid hot drinks” vs. “avoid sugary foods”. It seems potentially safer when the specifics stay the same, with only the wording and the proposed responses changing.

There was one more thing that worried me about the past, much broader than any of these specific issues: doctors were very sure their cures worked. I knew in principle that there were a lot of placebo cures and cherry-picking, but it’s another thing to have to read story after story of doctors trying ridiculous treatments – one of them had his patient eat soap to cleanse their circulation – and reporting that it definitely worked, every time, and patients who had been violently insane for years were restored to perfect health. I have worked in a lot of excellent psychiatric hospitals, and not one of them has worked anywhere near as well as people in the seventeenth century record their completely ridiculous mental health system of telling people not to reading novels to have worked.

Either everyone in the past is a total liar (given this effect, probably true), Foucault himself is a total liar (given the Ship of Fools thing, probably true), or we need even more constant vigilance than we’ve been applying thus far (alas, probably also true).

.png)