Joachim Wtewael, “Golden Age” (1605), oil on copper, 22.5 x 30.5 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (via Wikipedia)

On its own, a painting by Joachim Wtewael can seem like a two-dimensional manifestation of an absurdly complex gâteau — gorgeous, delicious, but perhaps best taken in in small servings. Gathered together in critical mass in the exhibition, Pleasure and Piety: The Art of Joachim Wtewael (Utrecht, Centraal Museum, traveling this year to Washington, DC and Houston, Texas), however, the paintings’ immaculate surfaces and fervid sensuality make an intoxicating but satisfying meal.

Wtewael (1566–1638) lived in Utrecht, the Netherlands in the early part of the seventeenth century when it was a hotbed, along with Haarlem, of a belated Northern interpretation of Italian Mannerism. Wtewael (imagine an “o” in front of the first W for an approximation of the pronunciation) reveled in the style’s artifice and intricacy for his entire career, long after the frank naturalism influenced by Caravaggio took over in Utrecht. His paintings certainly found patrons, but Wtewael’s whole buoyant enterprise was also kept afloat by his family’s lucrative trade in flax.

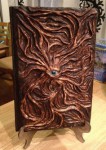

Wtewael often painted on copper, mostly on pieces about the size of a half a sheet of office paper. Copper doesn’t expand or contract with heat or humidity like wood or canvas, which means the painted surfaces can remain pristinely free of cracks or crazing. The metallic support, though invisible, also seems to give a special enameled richness to the paint, which Wtewael applies without visible brushstrokes. The painter wields this meticulous effect in Christian, mythological, and secular subjects, favoring scenes with multiple figures, the more nudes the better.

Joachim Wtewael, ”Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan” (1601), oil on copper, 21 x 15.5 cm. Mauritshuis, the Hague (via wikimedia.org)

Painting some subjects repeatedly but not repetitively, Wtewael juggles variables like setting, costume, and pose to create novel compositions with different inflections of meaning. A favorite motif was the love triangle of Venus, Mars, and Vulcan. In one version (Mauritshuis, 1601), the dynamic is about vision and exposure. In a richly appointed bedroom, Mars is wedged between Venus’s marmoreal loins. He looks up and shakes an angry finger at Mercury, who betrayed their affair to the other gods. Mercury stares back, as he lifts the acid-green canopy of their bed of passion, his watermelon pink hat flaring with the righteous indignation of a tattletale. From airy vantage points to the left, Jupiter, Minerva, Diana, Luna, and Saturn get their glimpse at the entrapped lovers. The wronged Vulcan enters from the viewer’s space, his leather apron flapping, his bare buttocks clenched and blushing with effort and pique. He is about to throw an immobilizing magical net over the pair, and as such stands for both artist and viewer, freezing the couple in time to gaze at their betrayal.

Joachim Wtewael, “Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan” (1604-1608), oil on copper 20.3 x 15.9 cm. Getty Museum (via Wikipedia)

In the version from the Getty collection (1604–08), the theme has become more salty and corporeal. The central dynamic of the painting is now the juxtaposition of Mars’ and Venus’ tangled limbs and, in a gap between the curtains of the bed, a view into Vulcan’s workshop. Vulcan is depicted twice; once in the foreground, again preparing to toss his net, and once in his workshop, the striking of his hammer on the hot metal evoking the couple’s copulation. To confirm the dirtier inflection, a spilling water jug under the bed in the Mauritshuis painting is replaced with a chamber pot, into which has dropped a corner of the bedspread.

Whatever the subject, Wtewael seems intent upon maximizing the illusion of three dimensionality. Compositions drill deep into pictorial space through carefully orchestrated shifts in value: foregrounds, often strewn with telling objects (such Mars’ discarded armor or Vulcan’s dropped hammer), are darkened with bands of shadow. The middle ground is brightly illuminated; this is followed by another swath of shadow, and then views, painted in filmy pastels, into the far distance. This effect is particularly strong in “The Adoration of the Shepherds” (1601, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart), where Wtewael pierces the dark stone wall of the crumbling barn behind the grouping around Christ with three windows, revealing scenes in the far distance, such as tiny shepherds receiving the news of Christ’s birth from an angel the size of a mosquito.

Along with these compositional techniques, the figures themselves seem to be creating space with their gestures, pushing outwards as if against a clear but confining film. Again, in the “Adoration”: with the exception of the Christ child, who reclines serenely in the center of the painting, everyone’s limbs seem to be in a state of hyperextension: Joseph, giving water to his donkey, balances on one knee and the ball of his foot, arms tracing an elliptical C, and Mary, gazing at the baby, splays her arms and fingers in a spasm of devotion. Two beefcake shepherds, their clinging rustic clothing exposing their shoulders, chest, and back, appear to have just completed a tumbling run to land in adoration beside Christ.

Wtewael also painted big, such as his “Perseus and Andromeda,” (1611, Louvre) — though surely, for this depiction of the myth, that habitual order of names should be reversed: Andromeda luminesces in most of the right foreground while Perseus and the dragon float in the middle distance like a pair of fighting betta fish. The transition of Wtewael’s technique from tiny sheets of copper to large-scale canvas is frictionless; the pictorial elements simply enlarge but lose no delicacy. There is, however, room to reveal yet more descriptive detail, such as the blue network of veins in Andromeda’s breasts, the sprinkle of water from the dragon’s snout, or the meticulous reportage on the features of the exotic shells that fill the foreground.

Joachim Wtewael, “Perseus and Andromeda” (1611), oil on Canvas, 180 x 150 cm. Louvre, Paris (via wikimedia.org)

Looking at his facture on a large scale, it is also possible to appreciate that, despite their satisfying volumetric solidity, there is no hard linear edge to his forms. The edges don’t resolve in a tight line, but modulate into a dark blur, as if the figures were made of a dense mist. Rather than circumscribed contours, it is their satiny sheen that lends them their startling sense of physical presence. Returning to the copper panels with new attention, one sees the same effect there, miniaturized.

Most stunning, perhaps, is the sheer copiousness within the images. The clear winner in this category is the different versions of “The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis,” which each present more than a hundred gods and goddesses in as many different poses. The subject gets competition from such paintings as “The Golden Age,” (1605, Metropolitan) a depiction of the idyllic life of the always-lost past, where satiny-bottomed women tend to babies while well-muscled men pluck food from trees. When he turns to a scene more connected to daily life, such as “Kitchen Scene with the Parable of the Great Supper,” (1605, Berlin), the many figures are replaced with just as many slithering piles of fish, dead game strung from shelves, and heaps of vegetables, all of which manage to radiate only marginally less sensuality than the nudes.

Joachim Wtewael, “Kitchen Scene with the Parable of the Great Supper” (1605), oil on canvas, 65 x 98 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie (via web gallery of art)

Despite the paintings’ charms, this is the first major museum exhibition of Wtewael’s works. It is not just the intimidating pair of consonants that begins his last name that has hindered his appreciation in the art world. From the perspective of evolutionist art history, Wtewael’s stylistic consistency looks like a fatal lack of engagement with the art of his time, like a society lady clinging to her bouffant hairdo after shags have become the norm. Recent art history has also viewed artistic angst as a marker of authentic creation. Wtewael’s only dilemma seems to have been to decide which mythological figure gets the most outlandish hat, or on which cast-of-thousands historical scene to spill his talent. This luscious show is as good a reason as any to ignore that perspective. Bring your magnifying glasses and your appetite.

Pleasure and Piety: The Art of Joachim Wtewael opens at the National Gallery of Art (National Mall between Third and Ninth Streets, along Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC) on June 28 and continue through October 4; from there it will travel to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where it will run from November 1, 2015 to January 31, 2016.

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America are pleased to announce the winners of the 2014 Nebula Awards (presented 2015), as well as the Ray Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation, and the Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy.

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America are pleased to announce the winners of the 2014 Nebula Awards (presented 2015), as well as the Ray Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation, and the Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy.