I spent a handful of years living in Turkey, and I’d like to take a little of your time discussing how Turkey went from a typical Eastern European country to the emergent Islamist state it is today.

I spent a handful of years living in Turkey, and I’d like to take a little of your time discussing how Turkey went from a typical Eastern European country to the emergent Islamist state it is today.

(This piece is by Sean-Paul Kelley – Ian)

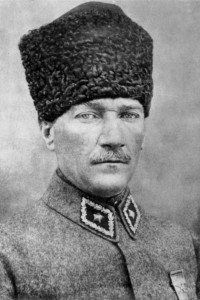

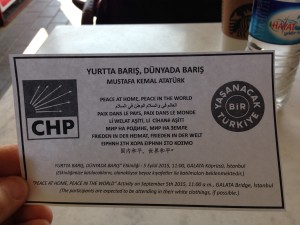

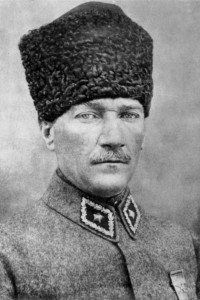

The last time I was in Turkey, in Fall 2015, the tension in the city was palpable. More Turks than ever before expressed, outright, their distaste and even hatred of Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the modern republic. Vastly different than my first visit in 2001, now it was all tension bordering on rude to inhospitable in late 2015. If you know anything about the Turks you’d have been shocked at the lack of hospitality.

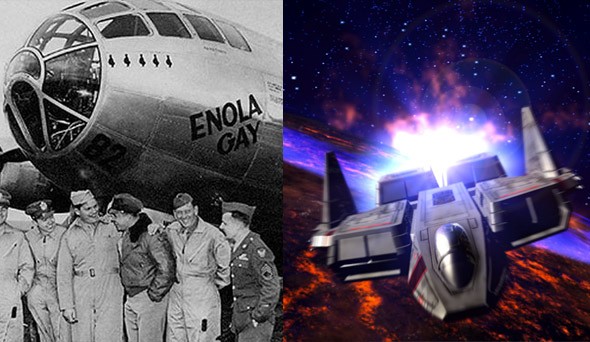

But it was the anger directed towards Ataturk in several conversations that had me so confused. As Walter Russell Mead notes, Atatürk’s accomplishments were great: “Kemal Atatürk rallied the remnants of the nation, defeated a Greek invasion, forced the Allies out of Constantinople and made Turkey a secular republic and an ethnic nation state on the European plan.” He also instituted deep and widespread internal reforms: Women’s rights, education, and the legal system were given rights and responsibilities were overhauled, and he built a new capital in Angora—Ankara—site of the Ottoman’s worst defeat until the 19th century. This defeat by Tamerlane in 1402 set the Ottoman project back by 50 years, and let Constantinople stagger on another 50 wasted years.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk would let nothing hold him back. He first major achievement came during the defense of Gallipoli. Stopping near the highest point in the area where the Allies advanced he noted their failure to capture the heights. amateurish moves on the part of the British generals, which would cost the souls of hundreds of thousands of men. But Kemal, ever moving forward, ordered his soldiers haul artillery to the top. There they were to pour a merciless, relentless stream of enfilading fire into the Allies lines, halting them permanently.

After WWI, Turkey faced the consequences of the Sykes-Picot Treaty, that dubious deposition of schoolboy skullduggery launched inside the bowels of an English gentleman’s club. Atatürk felt no obligation to adhere to the contemptible treaty and steeled himself for a fight against each of the Allies or, hopefully not, all at once. There would be no rump Turkey. Atatürk was a fighting general and he met the Franco-Armenian army first. They invaded form the East but, possessed by a Seljuk warrior, Atatürk sacrificed land for time until he met and defeated the Franco-Armenian invasion force at Marash in 1920. Rallying his soldiers for more hardship, for the Turks had their backs up against the wall between 1920-22. A year and a half after his defeat of the Franco-Armenian force, he met the Greeks at Sakarya, where he thrashed them so badly that even poor, old Gen. Venizelos, consumed of the great idea, Megali, Greater Greece, at long last conceded it was dead.

The end of the wars brought no respite for Atatürk, by now he had the reigns of the entire nation firmly in his grip. Working harder than ever, there he was, day after day, remaking Turkey along new lines: the nation-state. Here, he changed the alphabet, sent little girls to school, opened the faculty of Turkey’s greatest universities to foreigners, aiming for foreign knowledge and science and suspended Shari’a law in April, 1924. Turkish women gained the right to vote in local elections in 1930. Four years later, universal suffrage came to Turkey, sooner than many of its more “enlightened and advanced” Western neighbors. One of his greatest achievements, although this is beyond the scope of this essay, deserves mention: Ataturk abolished marriage for the misogynist, or what we call polygamy, in 1926. Had Muslim jurists been traveling along with Ataturk whispering in his ears that this is haram (forbidden), that is haram, all is haram, none of his achievements would have lasted a decade. Modern Turkey is impossible without Ataturk’s drive to secularize.

Atäturk, however, failed at two crucial problems, which when left to fester, as they would, troubled the young republic for the remainder of the century and beyond.

First, Atäturk and his brain trust never addressed the bigotry and discrimination shown towards the Alevi (Alawites if you are Suriani or live in Syria), which frequently led to what we would call pogroms. Second, the Kurds. I’m convinced Ataturk ignored the Kurds with a deep and abiding silence as a matter of policy. If he even whispered to someone that they existed then the logical conclusion demanded a state of their own, as Turkey had demanded based on Wilsonian principles of self-determination. Nationalism, that evil virus from Europe was spreading and all it has left the Kurds is death, destruction, blood and tears.

Even now the Kurds are a paradox, to others and to themselves. Turkey’s economic miracle was fueled by Kurdish immigrants willing to leave their dusty Anatolian farms for the balmy Aegean and Black Sea cities like Izmir, Bursa, Sinop and Trabzon have all benefited from the Erdoğonomics. So have the western Anatolian cities like Eskişehir, Afyon, Kayseri, Sivas and Konya. But the immigrants from the far eastern provinces bring their problems with them, especially those from the deep countryside. They are exceptionally conservative, the veil is never even spoken of. Daughter’s are chaperoned, a mother or aunt is fine, “after all,” a young woman friend of mine from Afyon once said, “we aren’t so backwards as the Saudis, although a little of their money would be nice.” This is paradox number one: they have gained tremendously from ‘Erdoğonomics’ even as the AKP and government as a whole treats them like shit. However, go out to Diyarbakir, Van or Urfa and it’s a different story. The Kurds proclaim their undying brotherhood with the Turks, they just “want to speak their own language and maybe watch TV in it. Is this not asking too much,” one young Kurd asked me back in 2009 during a multi-year lull in the violence. The answer: obviously no.

My neighborhood, Tophane, has changed enormously over the last few years. Once a party area for European backpackers, it’s now mostly Kurds, Zazaki speakers, not Kurmanj, and enough Syrian refugees to notice. Both groups wrapped up tight in the comforts of hejab, modest clothing for both men and women. One day even I was chided wearing shorts to the bodega to get a pack of gum. Mead notes that my nieghborhood was like many others across the peninsula. “In Ankara and Istanbul the generals, the statesmen and the businessmen live international and largely secular lives,” he writes, “Women went bareheaded, and, for the daughters of the upper middle class, the freedom of western secular life beckoned.” However, ominous clouds float above the economic success of Erdoğan, “in the cities and villages far from the metropolitan centers, in places like Konya and Gaziantep, something else was happening.” That something else was Anatolian peasants migrating en masse to plentiful jobs in the cities, but these migrants brought their piety with them and demanded everyone else live as they do.

My neighborhood, Tophane, has changed enormously over the last few years. Once a party area for European backpackers, it’s now mostly Kurds, Zazaki speakers, not Kurmanj, and enough Syrian refugees to notice. Both groups wrapped up tight in the comforts of hejab, modest clothing for both men and women. One day even I was chided wearing shorts to the bodega to get a pack of gum. Mead notes that my nieghborhood was like many others across the peninsula. “In Ankara and Istanbul the generals, the statesmen and the businessmen live international and largely secular lives,” he writes, “Women went bareheaded, and, for the daughters of the upper middle class, the freedom of western secular life beckoned.” However, ominous clouds float above the economic success of Erdoğan, “in the cities and villages far from the metropolitan centers, in places like Konya and Gaziantep, something else was happening.” That something else was Anatolian peasants migrating en masse to plentiful jobs in the cities, but these migrants brought their piety with them and demanded everyone else live as they do.

Hejab was mandatory in my mahalle, which makes me biased. That said, a novelist friend who lives in the Asian-side, uber-posh mahalle Moda, said even there the intolerance grew. Often it manifested itself as conservative men and women walked through the mahalle shouting at walkers, shaming them. Fatih—where the sumptuous Sulimaniye Mosque is—is terribly conservative. And even benighted Şişhane has been cleaned up a little, brothels moved to Zeytinburnu. In the suburbs it’s now a rough, blue-collar heroin infested mahalle of young unemployed male mayhem.

Hejab was mandatory in my mahalle, which makes me biased. That said, a novelist friend who lives in the Asian-side, uber-posh mahalle Moda, said even there the intolerance grew. Often it manifested itself as conservative men and women walked through the mahalle shouting at walkers, shaming them. Fatih—where the sumptuous Sulimaniye Mosque is—is terribly conservative. And even benighted Şişhane has been cleaned up a little, brothels moved to Zeytinburnu. In the suburbs it’s now a rough, blue-collar heroin infested mahalle of young unemployed male mayhem.

I loved the old, secular, Turkey.

All this as preamble to the coup, and what it will mean for the future.

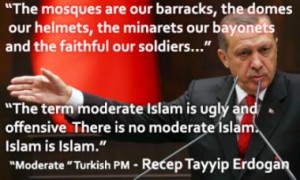

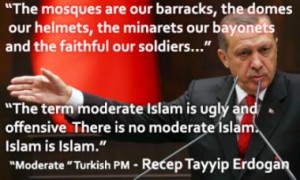

The moment I heard about the coup attempt in Turkey yesterday I posted my thoughts without pause or editing. My gut said “I seriously doubt the coup will take hold. Erdoğan cut far into the military muscle with Ergenekon.” The dying optimist in me, however, thought that “maybe it’ll last—and I hope it does—because Erdoğan is a vile, hateful little man.” My loathing for Erdoğan is spectacular, I hope his end resembles Ceaușescu’s, limbs torn from his body into shreds by an angry street mob, and not that of Islam Karimov, the leader who boiled his opponents alive yet will more than likely die peacefully in his large palace on a hill outside Tashkent overlooking the rolling Hungry Steppe.

Turkey’s military deserves an altogether different fate as units were trying to fulfill a constitutional purpose expected of them in the 20th century and/or two, they were lied into believing their movements into the streets of Istanbul were just an exercise. Whether they were lied to or not their highest constitutional duty has been the preservation of the secularism Kemal Atäturk imposed on the young nation he cobbled together in the late 20s and early 30s. Their duty is not the preservation of democracy, but of secularism.

American Liberals, Progressives and a handful of Conservatives usually incorrectly believe the Turkish army’s main goal is to promote and protect democracy. Democracy is not the only good, secularism is a good in an of itself.

But the army was never likely to succeed.

Why not? What was different this time? Why, in the past had the army been successful and Friday it was not?

In a word: Ergenekon.

In the old Turkish myths Ergenekon is a mythical “Land of Darkness,” a homeland cut clean and deep from the Archean rocks of the Tien Shan, a time when Titans and man roamed the Earth and man, terrified of the giants, sought shelter in the deep valleys the Tien Shan are famous for in search of their very own Shangri-la.

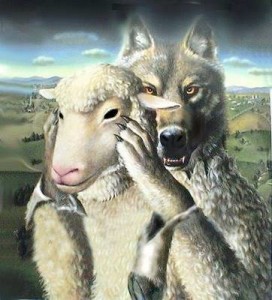

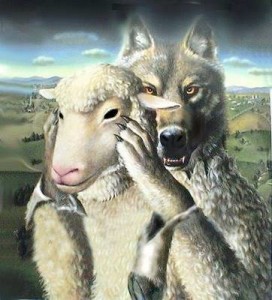

Erdoğan’s Ergenekon was the persecution of allegedly ultra-secular and nationalist (read: Kemalist) high ranking officers in Turkey’s armed forces, up to and including the general staff. Erdoğan conducted his military purge at great risk to himself, but with very good reasons based his own persecutions and jail-time at the hands of what we now Turkey’s deep state. Erdoğan’s left jail in 2003 and immediately became prime ministership—he feared a large group of officers would coalesced in opposition to the AKP-Gulenist alliance he led in parliament. (Allied at the time, Gulenists and Gulen himself apparently witnessed a bit too much immorality and tattled. This led to an irrevocable break between Erdoğan and Gulen.) There were fears in 2003 that AKP represented a brand of crypto pan-Islamism. Most analysts disputed this, using an analogy Americans would understand. Imagine if Pat Robertson’s hand-picked candidate won the presidency? It would not be a theocracy in America, would it? It sounds great, except that they were wrong.

Erdoğan’s Ergenekon was the persecution of allegedly ultra-secular and nationalist (read: Kemalist) high ranking officers in Turkey’s armed forces, up to and including the general staff. Erdoğan conducted his military purge at great risk to himself, but with very good reasons based his own persecutions and jail-time at the hands of what we now Turkey’s deep state. Erdoğan’s left jail in 2003 and immediately became prime ministership—he feared a large group of officers would coalesced in opposition to the AKP-Gulenist alliance he led in parliament. (Allied at the time, Gulenists and Gulen himself apparently witnessed a bit too much immorality and tattled. This led to an irrevocable break between Erdoğan and Gulen.) There were fears in 2003 that AKP represented a brand of crypto pan-Islamism. Most analysts disputed this, using an analogy Americans would understand. Imagine if Pat Robertson’s hand-picked candidate won the presidency? It would not be a theocracy in America, would it? It sounds great, except that they were wrong.

Protecting Turkey from this kind of pan-Islamism was part of the military’s job description. Under any other prime minister the military would have kicked him or her out office, brought order to the country and help elections as soon as possible thus preserving secularism in Turkey.

Ataturk and his immediate successors had good reason to believe that if a Muslim nation was to be modern it must embrace secularism. He looked at the chaos in Saudi Arabia, the emerging Hashemite Kingdoms and Egypt and their chronic inability to manufacture their own needs and support themselves. He believed in secularism first, then there could be democracy.

A portion of Turkey’s armed forces will soon be tried as traitors for their embrace of the Kemalist constitution. That’s just as Erdoğan would have it, too.

A disclaimer is needed here. No one likes generals sticking their noses into politics. Too often they end up like the Sphinx in Egypt: noseless, after the target practice of bored troops. Nor do I like it when generals engage in retail politics. President Clinton should have fired Colin Powell for insubordination when he wrote an op-ed opposing Clinton’s proposed gays in the military policy early in his first term. President Obama did fire one general who had the poor taste of telling the truth and getting caught. But there is a more recent case, this one quite scary, too. General Breedlove, former SACEUR, actively plotted against Obama’s Ukrainian-Russia policy. Breedlove contrary to President Obama’s express orders pushed for war. Once Obama learned of this he should have busted the general down to private and forced him to resign, on a private’s pension. Sadly, this is another example of old, clear lines of separation fraying in many of America’s most hallowed institutions. But I digress.

A disclaimer is needed here. No one likes generals sticking their noses into politics. Too often they end up like the Sphinx in Egypt: noseless, after the target practice of bored troops. Nor do I like it when generals engage in retail politics. President Clinton should have fired Colin Powell for insubordination when he wrote an op-ed opposing Clinton’s proposed gays in the military policy early in his first term. President Obama did fire one general who had the poor taste of telling the truth and getting caught. But there is a more recent case, this one quite scary, too. General Breedlove, former SACEUR, actively plotted against Obama’s Ukrainian-Russia policy. Breedlove contrary to President Obama’s express orders pushed for war. Once Obama learned of this he should have busted the general down to private and forced him to resign, on a private’s pension. Sadly, this is another example of old, clear lines of separation fraying in many of America’s most hallowed institutions. But I digress.

In America there is a clear separation (still) between civilian leaders and military brass; but, as mentioned above, modern Turkish precedent gives the military a special role, wide latitude to defend Kemal’s most important and lasting achievement: the secularization of Turkey. Secularism is the sine qua non of the Turkish Republic’s existence. Without it, Ataturk knew Turkey would flounder toward modernity, flailing and failing, until turning inward against the enemy within: the Alevi or the the Kurds. The Armenians had left, forcibly, and what few Greeks remaining either assimilated into Turkish culture as to be invisible, or were so old they were left alone and forgotten. Ataturk’s prescience was scarily precise, once the independence of the army was curbed, secularism would die. Turkish secularism perished before our eyes on June 15, 2016, after lasting almost a century.

A little clarity is necessary to avoid confusion: Erdoğan is not the prime minister, who is technically the most powerful individual in Turkey. Erdoğan is president now, one who is fighting to create a new constitutional order in Turkey where the president, a once ceremonial job only becomes the alpha of all alphas.

Is Tayyip America’s stooge? He most certainly is not. He is an Islamist, an elected one. On multiple occasions. But because he also implemented the right conditions for the economy to soar for almost ten years—when he was elected it cost 10,000,000 lira to buy a glass of tea. At one point the Lira to dollar exchange rate was 1.6 Lira to the dollar. He tamed inflation and then European light manufacturing investment money poured in to the country. It was an economic miracle.

This gave him an enormous amount of political capital that he’s been living off of ever since. He also had a skilled foreign minister, Davotoglu, who brought a real peace between the Kurds and Turkey. I was in Diyarbakir in 2008 and it was lovely. Meanwhile, many Kurds began migrating from the countryside to the cities along the Aegean and Black Sea where jobs were to be found.

They also blew Istanbul up like a balloon. In 2003 the population was 7 million. Today it is roughly 14 million. Most of the Kurdish migrants are very conservative religiously and with the peace seeming lasting, combined with the Kurdish leader, Abdullah Ocalan’s death sentence being commuted by Prime Minister Ecevit in 2002, Turkey’s future seemed positive. Add to that a last IMF/World Bank bailout to solidify Turkey’s perennially troublesome, embezzled banks. The growth was impressive. But as Walter Russell Mead writes the wheel turns and those once ignored will soon rule, “Atatürk’s Turkey marginalized the pious Anatolian peasants; now their grandchildren and great grandchildren are building a new Turkey. They see themselves storming the citadels of cosmopolitan, urban privilege in much the same way that Sultan Mehmet Fatih, the Conqueror, took Constantinople from the last Byzantine emperor. They have come to the cities like Mehmet and his warriors, and they are remaking them in their image.” This they did.

After almost a decade a speed bump crept up on Turkey’s leaders. The Arab Spring arrived and to everyone’s surprise the wheels came of economic and foreign policy. The foreign policy he and Davutoğlu implemented, “Zero Problems with Neighbors” fell apart. Had one observed closely signs pointed to the unraveling of the Turco-Israeli Entente. First, Turkey and Israel verbally sparred over who would sit where during negotiations for their next summit meeting. Traditionally the host nation had the high seat but Netanyahu and Lieberman had a new government, necessitating they prove themselves to constituents back home and hatched a plot to humiliate Erdoğan. Erdoğan being a man who never forgets a slight soon saw an opportunity for a propaganda victory against Israel: the Gaza Blockade.

Then Turkey sent the Mavi Mara and it was a PR disaster for Israel. Erdogan learned an important lesson: if there is an enemy abroad he can maintain and increase his power. Why? During this time his party the AKP won an outright majority in a parliament historically fragmented and factious. He has been doing this ever since. I

Turkey has a long history of expecting and appreciating the military stepping in as guarantor of secularism in the country. The military is not and never has been the guarantor of democracy. This is a fundamental support beam in Turkey.

But not on Friday.

Pepe Escobar autopsies the scene, cutting straight through to the viscera: “in the end they did not have the numbers – and the necessary preparation. All key ministries seemed to be communicating among themselves as the plot developed, as well as the intel services. And as far as Turkish police as a whole is concerned, they are now a sort of AKP pretorian guard.”

Pepe Escobar autopsies the scene, cutting straight through to the viscera: “in the end they did not have the numbers – and the necessary preparation. All key ministries seemed to be communicating among themselves as the plot developed, as well as the intel services. And as far as Turkish police as a whole is concerned, they are now a sort of AKP pretorian guard.”

Escobar then unloads an idea that floated around NatSec circles on Twitter and Facebook in the hours after the coup seemed doomed: somehow Erdoğan had foreknowledge of the plot, knew it to be weak and let it proceed secure and possibly giddy over the giant power-grab he’d soon achieve.

Escobar explains, “Erdoğan’s intel services knew a coup was brewing; and the wily Sultan let it happen knowing it would fail as the plotters had very limited support. He also arguably knew – in advance— even the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), whose members Erdoğan is trying to expel from parliament, would support the government in the name of democracy.”

Unlike all the windbags and chatterboxes on TV or the earnest but easily mislead Knights of Keyboard Manor thwacking bits and bytes across the ‘net, using words like Reichstag and False Flag without a shred of evidence to support their suppositions other than a gut feeling, Escobar does something radical: he offers some very plausible evidence for his theory. Like a modern day I.F. Stone, cutting through an overload of giga-this and peta-that, Seńor Escobar informs his readers how “[e]arlier last week Erdoğan signed a bill giving soldiers immunity from prosecution while taking part in domestic security ops – as in anti-PKK (but hypothetically this law could be used to excuse soldiers who were unknowingly misled into participating ed. note ~spk); that spells out improved relations between the AKP government and the army. And then Turkey’s top judicial body HSYK laid off no less than 2,745 judges after an extraordinary meeting post-coup. This can only mean the list was more than ready in advance.” (Emphasis mine.) This same thought was expressed by a friend and I’m with her and Escobar: it’s more than plausible, it’s probable.

Those who thought Erdoğan had been wounded badly over the confrontation with Russia—even the United States began evacuating non-essential military and diplomatic personnel after the fallout with Russia and a spate of terrorist bombings—are now watching the biggest power grab in Turkey since 1908 when 200 “Young Turks” demanded the reinstatement of the Constitution of 1876. Sultan Abdul Hamid II refused on principle, only to watch revolt spread like wildfire on the steppe across his ever shrinking patrimony, until he capitulated. The Turks may call Erdoğan “the Little Sultan” as an insult on the sly, but he’s got some big ole’ britches now, britches that will only get bigger.

Those who thought Erdoğan had been wounded badly over the confrontation with Russia—even the United States began evacuating non-essential military and diplomatic personnel after the fallout with Russia and a spate of terrorist bombings—are now watching the biggest power grab in Turkey since 1908 when 200 “Young Turks” demanded the reinstatement of the Constitution of 1876. Sultan Abdul Hamid II refused on principle, only to watch revolt spread like wildfire on the steppe across his ever shrinking patrimony, until he capitulated. The Turks may call Erdoğan “the Little Sultan” as an insult on the sly, but he’s got some big ole’ britches now, britches that will only get bigger.

What kind of actions can be expected from Erdoğan once the coup dust settles, a friend asked the evening of the coup? “The immediate consequence,” explains Pablo Escobar, “is that Erdoğan now seems to have miraculously reconquered his ‘strategic depth’” both internally and externally. In laymen’s terms: he’s more powerful now domestically—look for purges—even after the fiasco that was Syria and with Russia’s shot down jet, and more. Plus the unholy Kurdish mess, including its lack of real policy doesn’t much matter. Erdoğan’s much like Bismarck in 1866 after defeating the Austrians at the Battle of Königgrätz. “Bismarck punched his fist on his desk,” writes historian Jonathan Steinberg, “and cried “I have beaten then all! All!’”

Neo-Ottomanism, Turkey’s version of Neo-conservativism, previously almost discredited, is now in the ascendant. Neo-Ottomanism can be described as “a dramatic shift from the traditional Turkish foreign policy of the Kemalist [type], which emphasized looking westward towards Europe with the goal of avoiding the instability and sectarianism of the Middle East (emphasis added).” Instead “Neo-Ottomanism promotes greater political engagement (read: interference) of the modern Republic of Turkey within regions formerly under the rule of the Ottoman Empire” of which it is a successor state. In practical terms this means more intervention in Syria, a continuance in the break with Israel, possible incursions into Iraqi-Kurdistan for which there is a 1990s precedent by former Prime Minister Tansu Çiller.

If Erdoğan was previously perceived as a bit unbearable, something of a hothead, he’ll be insufferable now and for the foreseeable future. How big a chair at the big boys table is he going to demand? With NATOs second largest armed forces of 640,000 troops, it’ll be fairly sizable.

For the foreseeable future Turkey’s fate is inextricably bound with that of President Erdoğan. With Erdoğan in such a commanding role in regards to his peers and the club he wants to join in Davos, it’s going to be tough when he’s ironically bested by the only leader the West cannot stomach, Vladimir Putin. Is this an opening for Putin and Erdoğan to settle the Armenian issue?

Might Putin shave Erdoğan and Turkey away from the Atlantic Alliance? Putin and Erdoğan share similar conservative domestic and foreign policy ideologies. What of the NATO-Turkish partnership? Does Turkey close İncirlik Air Force Base every time it gets an itch, or wants to retaliate for some perceived slight? Erdoğan is notorious for perceiving slights where none exist. For instance, he walked out of a speech by Shimon Peres because Peres hurt his feeling, then Erdoğan used it as an excuse to dissolve the entente between Israel and Turkey. Is this the kind of behavior NATO can expect? Even now İncirlik Air Force Base is closed to US flights. Consider: İncirlik is “home to A-10s, the most reliable manned aircraft the US possesses for providing air support to ground forces fighting Isis.” Is this a temporary bug or long-term feature?

Then there is the domestic American fallout. Facts are curious things. In the case of Turkey the many Islamaphobes in the USA (and some of Western Europe) will no doubt inform everyone, correctly, too, that Turkey is governed by Islamists. Then they, or someone like them will point out how NATO—and by NATO I mean the USA who foots 75% of NATO’s bill—is legally and morally obligated to defend Turkey if attacked by an outside force, be it Iran, Syria, Iraq, Russia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Armenia or even Fiji. Is it plausible to imagine a situation where Turkey’s new found èlan might hold the great Atlantic alliance, and America’s 60-70 tactical nuclear weapons currently based in Turkey, hostage? What price would we be willing to pay? Would we extradite Muhammed Fethullah Gülen, once Erdoğan’s partner but now his bête noire. Would we evacuate İncirlik?

How these questions and many others unfold in the near future depend on voters in other nations, plus those in the United States who get to choose between the fascistic Donald Trump and the corporate sellout and former Goldwater Girl, Hillary Clinton.

The voters of the Western democracies must be bewildered (and a bit exhausted) at present. Consider that the following events have occurred in the span of seven days: Brexit, a new British PM, a possible ITexit, an attempted coup in Turkey, and a terrorist attack in Nice, France. Did I miss anything? I’m certain I did. Regardless, all these events give voters everywhere a complicated set of variables to digest before even considering domestic matters, much less voting on them. No wonder everone wants to be on antidepressants. What a week.

I don’t think Erdoğan is lacking in the pelotas o huevos department. I do think he believes his own PR—and when leaders begin to do that they quickly lose touch with the people who put them where they are. That spells trouble. But, that’s for another post. I want to address another crucial point: “If Gulen and his organization were really behind the coup that means it was orchestrated by the CIA.” For the life of me, and perhaps I am naive or just credulous enough to believe the CIA would never get into bed with the Gulenists, I find this rumor making the rounds implausible. The Gulenists stand for everything the United States is opposed to, at least rhetorically. Further, I don’t see Gulenist-American interests in alignment here, either. If you have more, please elucidate.

______________________________________________________________

Just a short while ago this headline scrolled across the television: Judicial Reform Comes to Turkey at Long Last. As widely known, the courts in Turkey have long proven to be Erdoğan’s prime obstacle in recreating the constitution in his image. The news story implied that in the midst of the coup attempt, members of the courts were being rounded up, detained and/or arrested. 188 arrest warrants were issued for members of the High Council of Judges and Prosecutors—Turkey’s highest official judicial body—five members were removed at an emergency meeting Saturday morning..

Ever the cagey one, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is taking no chances. While taking on the Hugh Courts he slashes through the lower courts like Alexander sliced through the Gordian Knot. “2,745 judges of duty [in total],” writes RT, were fired Saturday morning.

All of this leads us inexorably to the possible conclusion that the coup was premeditated and orchestrated by Erdoğan or one of his key allies. An Anglo-American court of law would judge this behavior premeditated, indicating clear intent on the part of the anti-coup party, Little Sultan Erdoğan his own self.

So, why is that important?

I’ll let esteemed Col. Lang explain:

“What I am hearing from sources in Turkey is that this was a pre-emptive false flag designed to fail in which the people sent into the coup were sacrificed by their superiors who are Erdoğans adherents in the armed forces.”

If these judicial dismissals aren’t a smoking gun, they’re at least warm shell casings. They point to further purges in the days ahead. How far Erdoğan goes—civil servants, public school teachers, regional administrative workers—no one knows.

Over the weekend of July 15-17, there were several more developments furthering the claim that the coup was a set-up by Erdoğan or that he knew it was coming. First, there was the demand by Erdoğan and his surrogates in the media that the United States must give up Fethullah Gulen before any activites at İncirlik Air Force Base could be resumed. To prove how serious the Turks were several actions were taken to rattle the Americans based there. First, the power was shut off and remained off for at least three days. Pro-Erdoğan prosecutors then raided the air force base, accusing Americans of hiding pro-coup generals and others loyal to Gulen. Following these incidents the air force base was “blocked by Turkish military authorities” and placed under siege. Nothing is going into the base and nothing is coming out. As of 9:40 PM last night the base was still without electricity and remained surrounded by the Turkish military in what is fast becoming the century’s greatest game of chicken, this one between Erdoğan and NATO.

As of this writing—10:12 am Central Time—the total number of those purged is somewhere between 50,000-60,000 Turks deemed disloyal to Erdoğan, the AKP and/or supporter(s) of the Gulenist-terror organization. The BBC writes, “The purge of those deemed disloyal to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan widened on Tuesday to include teachers, university deans and the media.”

With these measure Erdoğan is cutting broad and deep, like Stalin, before him; eliminating potential sources of opposition before they can coalesce into revolt. With the sacking of teachers, however, it’s clear one of his main aims is the complete destruction of the Kemalist-Secular order in Turkey. Schools have been the repository of Ataturk’s legacy. Where Turkish children have their first encounter with Ataturk, the father of the modern Republic of Turkey. Sweeping away secular teachers will change Turkey irrevocably.

There is more to the purges than just schools. 9,000 people are in custody, for starters and expected to rise much higher. With numbers like these it’s clear that President Erdoğan’s claim the purges are necessary to “cleanse all state institutions” of members of the Gulenist-clique is a lie.

As of 3:00 AM US Central Daylight Savings, the BBC estimated the following have been purged with more to follow:

-

7,500 soldiers have been detained, including 118 generals and admirals

-

8,000 police have been removed from their posts and 1,000 arrested

-

3,000 members of the judiciary, including 1,481 judges, have been suspended

-

15,200 education ministry officials have lost their jobs

-

21,000 private school teachers have had their licenses revoked

-

1,577 university deans (faculty heads) have been asked to resign

-

1,500 finance ministry staff have been removed

-

492 clerics, preachers and religious teachers have been fired

-

393 social policy ministry staff have been dismissed

-

257 prime minister’s office staff have been removed

-

100 intelligence officials have been suspended

Again, the BBC makes a crucial observation: “The purge is so extensive that few believe it was not already planned. And there seems little chance that everyone on the list is a Gulenist.”

Some immediate results of the counter-coup and purges: Turkey’s tourism industry (13 percent of GDP) will die. It is unknown what will happen to the EU manufacturing investments made in country over the last 13 years. Will Turkey remain the Continent’s light manufacturer of choice? At three lira to the dollar odds are it will.

Questions remain, however, festering, itching, and irritating. For example, why does the Civil Service make up such disproportionate numbers? The BBC has an interesting, if sad, answer: “The government is weeding out opponents from Turkey’s Alevi community, which numbers some 15 million.” The Turks spell it Alevi, but President Erdoğan’s enemy to the South, Bashar al-Assad, president of Syria, calls himself an Alawite. The names are identical.

And what of the poor benighted Kurds? More ambivalence, I say. The status quo, but a violent one, if that makes any sense. Continued migration into cities like Istanbul, Ankara, Eskişehir, Balıkesir, Izmir, Trabzon will face more pressure on already aging infrastructure.

What are we to look for next? A few obvious variables come to mind first. Exit visas. For example, just this morning we learned that Erdoǧan issued a blanket foreign travel ban on all Turkish academics. Curfews in selected areas, those known to have opposed President Erdoğan in the past. Detentions without charge are not without precedent in situations such as these in Turkey. Extended purges from the civil service. Reinstatement of the death penalty have been sent up as a trial balloon in several media outlets.

If, as I believe, Erdoğan’s ultimate aim is to remake Turkey into a fully Islamic society, religious judges, or qadis, will be placed in the former positions of their secular counterparts. Moreover, hejab, or modest dress, will be imposed upon women, thus remaking Turkey into an Aegean Iran overnight. This will be followed by the creation of a morality division of the current police departments. All of this might require the abolition of parliament. At that point NATO has a serious decision to make, if Turkey hasn’t already abrogated the North Atlantic Treaty: Stay and tacitly support Erdoğan—supporting despots in the region is SOP—or go, using one of the Balkan nations for operations conducted out of İncirlik Air Force Base. None of this would surprise me now.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, for whatever reason, feels compelled to sweep away the entirety of the old order; the Kemalist-Secular order that jailed him multiple times, but also the same order that brought stability and safety to a shaky new Turkish Republic formed in April, 1920.

As of this writing, it appears Erdoğan and his henchmen in the AKP will succeed. Turkey’s civil society will be dragged back 100 years under the guise of modernity and religion, the greatest paradox of our age. For this writer, however, it’s heartbreaking. Turkey was a second home, and I grieve its loss keenly, every day.

If you enjoyed this article, and want more, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: [Image: Deception Island, from Millett G. Morgan’s September 1960 paper An Island as a Natural Very-Low-Frequency Transmitting Antenna].

[Image: [Image: Deception Island, from Millett G. Morgan’s September 1960 paper An Island as a Natural Very-Low-Frequency Transmitting Antenna]. [Image:

[Image:

Christopher Chant is the Chrestomanci, or head honcho of monitoring the use of magic across the multiverse.

Christopher Chant is the Chrestomanci, or head honcho of monitoring the use of magic across the multiverse.  Some of my favorite books by fantasy fiction writers is when they twist into weird non-fiction. Douglas Adams’ The Meaning of Liff is basically what a dictionary written by P.G. Wodehouse would sound like. Neil Gaiman’s Ghastly Beyond Belief is some of the weirdest stuff he’s ever written.

Some of my favorite books by fantasy fiction writers is when they twist into weird non-fiction. Douglas Adams’ The Meaning of Liff is basically what a dictionary written by P.G. Wodehouse would sound like. Neil Gaiman’s Ghastly Beyond Belief is some of the weirdest stuff he’s ever written.

Jones won or was a finalist in the Mythopoeic Fantasy Awards multiple times, so you have your pick of titles. However, I’d recommend

Jones won or was a finalist in the Mythopoeic Fantasy Awards multiple times, so you have your pick of titles. However, I’d recommend  Most of Diana Wynne Jones’ books are aimed at children and young adults, but she’s also branched out into younger children and adult readers. Who Got Rid of Angus Flint? (1978) is a delightful little picture book about an unwanted friend of the family who stops by unexpectedly and just won’t leave. With only six chapters, it’s a light, fun book for young book lovers practicing their reading skills.

Most of Diana Wynne Jones’ books are aimed at children and young adults, but she’s also branched out into younger children and adult readers. Who Got Rid of Angus Flint? (1978) is a delightful little picture book about an unwanted friend of the family who stops by unexpectedly and just won’t leave. With only six chapters, it’s a light, fun book for young book lovers practicing their reading skills. A bit darker and more mature,

A bit darker and more mature,