Interplanetary Cessna

What would happen if you tried to fly a normal Earth airplane above different Solar System bodies?

—Glen Chiacchieri

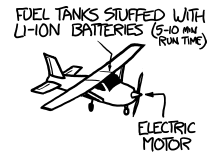

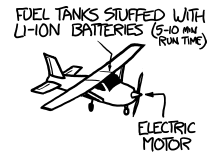

Here’s our aircraft:

The Cessna 172 Skyhawk, probably the most common plane in the world.

Here’s our pilot:

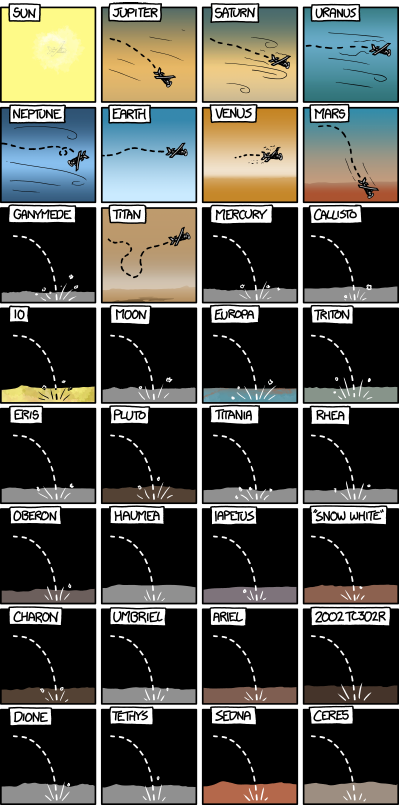

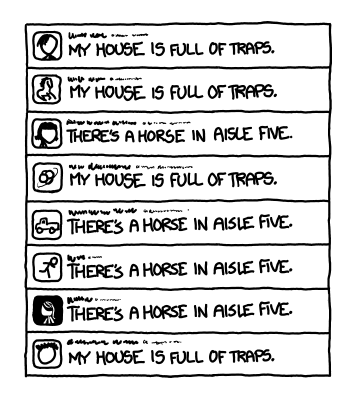

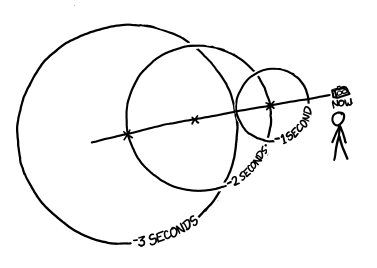

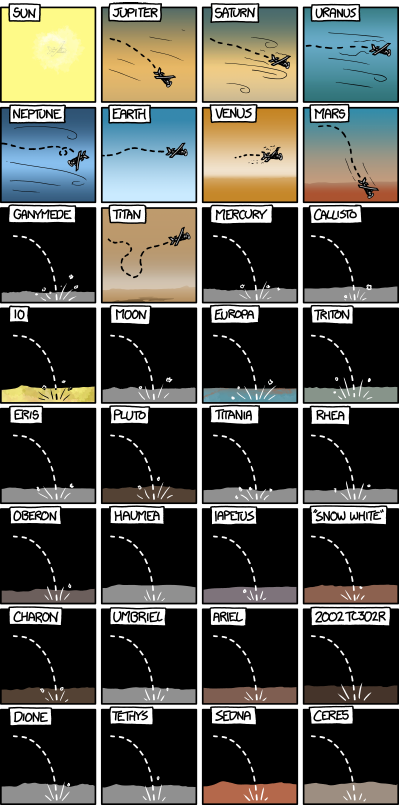

Here’s what happens when the aircraft is launched above the surface of the 32 largest Solar System bodies:

In most cases, there’s no atmosphere, and the plane falls straight to the ground. (If it’s dropped from one kilometer, in a few cases, the crash will be slow enough that the pilot may survive—although the life-support equipment probably won’t.)

There are nine Solar System bodies with atmospheres thick enough to matter: Earth—obviously—Mars, Venus, the four gas giants, Saturn’s moon Titan, and the Sun. Let’s take a closer look at what would happen to a plane on each one.

The Sun: This works about as well as you'd imagine. If the plane is released close enough to the Sun to feel its atmosphere at all, it's vaporized in less than a second.

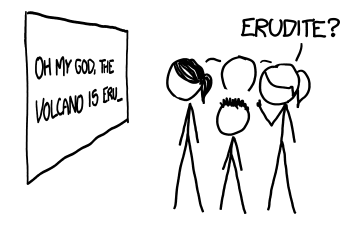

Mars: To see what happens to aircraft on Mars, we turn to X-Plane.

X-Plane is the most advanced flight simulator in the world. The product of 20 years of obsessive labor by a hardcore aeronautics enthusiast who uses capslock a lot when talking about planes, it actually simulates the flow of air over every piece of an aircraft’s body as it flies. This makes it a valuable research tool, since it can accurately simulate entirely new aircraft designs—and new environments.

In particular, if you change the X-Plane config file to reduce gravity, thin the atmosphere, and shrink the radius of the planet it can simulate flight on Mars. (Note: Thank you to Tom J and the folks in the X-Plane community for their help with aerodynamic calculations in different atmospheres.)

X-Plane tells us that flight on Mars is difficult, but not impossible. NASA knows this, and has considered surveying Mars by airplane. The tricky thing is that with so little atmosphere, to get any lift, you have to go fast. You need to approach Mach 1 just to get off the ground, and once you get moving, you have so much inertia that it’s hard to change course—if you turn, your plane rotates, but keeps moving in the original direction. The X-Plane author compared piloting Martian aircraft to flying a supersonic ocean liner.

Our Cessna 172 isn’t up to the challenge. Launched from 1 km, it doesn’t build up enough speed to pull out of a dive, and plows into the Martian terrain at over 60 m/s (135 mph). If dropped from four or five kilometers, it could gain enough speed to pull up into a glide—at over half the speed of sound. The landing would not be survivable.

Venus: Unfortunately, X-Plane is not capable of simulating the hellish environment near the surface of Venus. But physics calculations give us an idea of what flight there would be like. The upshot is: Your plane would fly pretty well, except it would be on fire the whole time, and then it would stop flying, and then stop being a plane.

The atmosphere on Venus is over 60 times denser than Earth’s, which is thick enough that a Cessna moving at running speed would rise into the air. Unfortunately, the air it’s rising into is hot enough to melt lead. The paint would start melting off in seconds, the plane’s components would fail rapidly, and the plane would glide gently into the ground as it came apart under the heat stress.

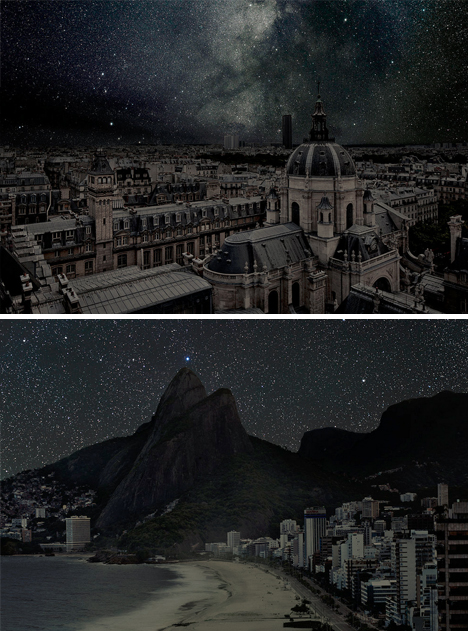

A much better bet would be to fly above the clouds. While Venus’s surface is awful, its upper atmosphere is surprisingly Earthlike. 55 kilometers up, a human could survive with an oxygen mask and a protective wetsuit; the air is room temperature and the pressure is similar to that on Earth mountains. You need the wetsuit, though, to protect you from the sulfuric acid. (I’m not selling this well, am I?)

The acid's no fun, but it turns out the area right above the clouds is a great environment for an airplane, as long as it has no exposed metal to be corroded away by the sulfuric acid. And is capable of flight in constant Category-5-hurricane-level winds, which are another thing I forgot to mention earlier.

Venus is a terrible place.

Jupiter: Our Cessna can’t fly on Jupiter; the gravity is just too strong. The power needed to maintain level flight is three times greater than that on Earth. Starting from a friendly sea-level pressure, we’d accelerate through the tumbling winds into a 275 m/s (600 mph) downward glide deeper and deeper through the layers of ammonia ice and water ice until we and the aircraft were crushed. There's no surface to hit; Jupiter transitions smoothly from gas to solid as you sink deeper and deeper.

Saturn: The picture here is a bit friendlier than on Jupiter. The weaker gravity—close to Earth’s, actually—and slightly denser (but still thin) atmosphere mean that we’d be able to struggle along a bit further before we gave in to either the cold or high winds and descended to the same fate as on Jupiter.

Uranus: Uranus is a strange, uniform bluish orb. There are high winds and it’s bitterly cold. It’s the friendliest of the gas giants to our Cessna, and you could probably fly for a little while. But given that it seems to be an almost completely featureless planet, why would you want to?

Neptune: If you’re going to fly around one of the ice giants, Neptune (Motto: “The Slightly Bluer One”) is probably a better choice than Uranus. It at least has some clouds to look at before you freeze to death or break apart from the turbulence.

Titan: We’ve saved the best for last. When it comes to flying, Titan might be better than Earth. Its atmosphere is thick but its gravity is light, giving it a surface pressure only 50% higher than Earth’s with air four times as dense. Its gravity—lower than that of the Moon—means that flying is easy. Our Cessna could get into the air under pedal power.

In fact, humans on Titan could fly by muscle power. A human in a hang glider could comfortably take off and cruise around powered by oversized swim-flipper boots—or even take off by flapping artificial wings. The power requirements are minimal—it would probably take no more effort than walking.

The downside (there’s always a downside) is the cold. It’s 72 kelvin on Titan, which is about the temperature of liquid nitrogen. Judging from some numbers on heating requirements for light aircraft, I estimate that the cabin of a Cessna on Titan would probably cool by about two degrees per minute.

The batteries would help to keep themselves warm for a little while, but eventually the craft would run out of heat and crash. The Huygens probe, which descended with batteries nearly drained (taking fascinating pictures as it fell), succumbed to the cold after only a few hours on the surface. It had enough time to send back a single photo after landing—the only one we have from the surface of a body beyond Mars.

If humans put on artificial wings to fly, we might become Titan versions of the Icarus story—our wings could freeze, fall apart, and send us tumbling to our deaths.

But I've never seen the Icarus story as a lesson about the limitations of humans. I see it as a lesson about the limitations of wax as an adhesive. The cold of Titan is just an engineering problem. With the right refitting, and the right heat sources, a Cessna 172 could fly on Titan—and so could we.