Submitted by: Unknown

Shared posts

Please design me a dog house

In June of 1956, Frank Lloyd Wright — a man posthumously recognised as "the greatest American architect of all time" by the AIA — received an unusual letter from 12-year-old Jim Berger, a boy looking to commission the design of a home for his dog, Eddie, by the same architect who designed his father's house 6 years previous. Incredibly, Frank Lloyd Wright agreed and, as seen below, supplied a full set of drawings for "Eddie's House" the next year. Construction was eventually completed by Jim's father in 1963.

Eddie hated his new home. It was demolished in 1973.

The full exchange can be found below, along with a photo of the completed dog house. It was the smallest structure ever designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and possibly the least used.

(Sources: Architizer & Deborah Wright; Image: Frank Lloyd Wright, via Wikimedia.)

Transcript

June 19, 1956

Dear Mr. Wright

I am a boy of twelve years. My name is Jim Berger. You designed a house for my father whose name is Bob Berger. I have a paper route which I make a little bit of money for the bank, and for expenses.

I would appreciate it if you would design me a dog house, which would be easy to build, but would go with our house. My dog's name is Edward, but we call him Eddie. He is four years old or in dog life 28 years. He is a Labrador retriever. He is two and a half feet high and three feet long. The reasons I would like this dog house is for the winters mainly. My dad said if you design the dog house he will help me build it. But if you design the dog house I will pay you for the plans and materials out of the money I get from my route.

Respectfully yours,

Jim Berger

Transcript

Dear Jim:

A house for Eddie is an opportunity. Someday I shall design one but just now I am too busy to concentrate on it. You write me next November to Phoenix, Arizona and I may have something then.

Truly yours,

Frank Lloyd Wright

June 28th, 1956

Transcript

Dear Mr Wright

I wrote you June 19, 1956 about designing my dog Eddie a dog house to go with the house you designed for my dad. You told me to write you again in November so I ask you again, could you design me a dog house.

Respectfully yours,

Jim Berger

The Result

RSS Feed proudly sponsored by TinyLetter, a simple newsletter service for people with something to say.

Wes Anderson and Kanye West Are Perfect Together

When you think about it, Kanye West and Wes Anderson have a lot in common — and no, we’re not talking about a certain string of letters, though it does make for some nice assonance/consonance. Both men have a double whammy of cult and mainstream appeal, both take great care with their visual presentation, and both rock the hipster nerd thing like nobody’s business. So when Juxtapoz pointed us to this amazing Tumblr mashing up Kanye lyrics with Anderson films (and sometimes Anderson dialogue with images of Kanye), all we could think was: of course. And then we started laughing. Click through to see a few of our favorite mashups, and then be sure to head over to Kanye Wes for many more ironic gems.

The Royal Tenenbaums / “Love Lockdown.” Image credit: Kanye Wes

“Runaway” / Moonrise Kingdom. Image credit: Kanye Wes

The Royal Tenenbaums / “No Church in the Wild.” Image credit: Kanye Wes

Moonrise Kingdom / “Birthday Song.” Image credit: Kanye Wes

Rushmore / Kanye West. Image credit: Kanye Wes

The Royal Tenenbaums / “All of the Lights.” Image credit: Kanye Wes

Fantastic Mr. Fox / “Clique.” Image credit: Kanye Wes

Rushmore / “Can’t Tell Me Nothing.” Image credit: Kanye Wes

The Royal Tenenbaums / “Power.” Image credit: Kanye Wes

Moonrise Kingdom / “Runaway.” Image credit: Kanye Wes

Sebastian Horsley: Never an Ordinary Man, an interview from 1995

The artist, writer and dandy Sebastian Horsley claimed he was an accident, the product of a split condom. His mother drank through her pregnancy, and tried to abort the unwanted child. She failed and Sebastian was born in 1962. This might explain Horsley’s difficult relationships with women in later life, preferring to use prostitutes rather than share any emotional intimacy with another.

Horsley was originally called Marcus, which he may have preferred as it was closer to his idol Marc Bolan. But after registering his name as a baby, Horsley’s mother knew she had made a mistake, and opted instead for Sebastian. It only took her 5 years to change it by deed poll.

The name Sebastian suited Horsely. It suggested the Christian martyr Saint Sebastian, who was tied to a tree and shot full of arrows for his faith. In the same way Horsely was nailed to a cross in the Philippines for his art. Or, Sebastian Flyte - Evelyn Waugh’s character from Bridehead Revisited, whose beauty and desire were numbed by addiction to alcohol. As Horsley in his way was addicted to heroin and cocaine - a mixture of which eventually killed him. Or, Sebastian Dangerfield, J. P. Donlevy’s dissolute bohemian artist of The Ginger Man.

Horsley briefly attended St. Martin’s Art College but was kicked out after only a few months.

“I don’t think by going to college you can really achieve anything whatsoever - except perhaps they teach you how to be ordinary.”

He taught himself how to be an artist, and saw painting as a way of creating a new, unspoken language. Yet, he often felt incapable of expressing this language, and destroyed many of his paintings. He died in 2010 from an accidental overdose, leaving a life that was, in many respects, his greatest work of art.

In this brief interview from 1995, Sebastian Horsley talks about his background, his view of art, and his sartorial style.

Coming Distractions: Trailer: The Arrested Development Documentary Project

Since 2007, a duo of self-described Arrested Development "superfans" has been diligently working on The Arrested Development Documentary Project, a film whose purpose is as Ann as the nose on plain's face, in the absolute last reference we're going to make in this article. Now that the show is due for an unexpected fourth-season revival, the filmmakers are finally ready to release (somewhere, at some time) their ongoing attempt to "provide awareness" of their beloved, canceled show, because they may as well because Netflix ruined it. After all, there's little to no need to "provide awareness" of the show these days, now that it's alive again and the Internet is doing such an excellent daily job of that. But still, their documentary collects interviews from its cast and creators that all look like they're going to be pretty funny, so that's something.

Read moreGlenn Gould Explains the Genius of Johann Sebastian Bach (1962)

The Canadian pianist Glenn Gould was one of the most brilliant and idiosyncratic interpreters of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. In this 1962 special for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Gould reveals the same brilliance and idiosyncrasy in his understanding of Bach’s place in history.

Bach, says Gould, was not so much ahead of his time as outside it. “For Bach, you see, was music’s greatest non-conformist, and one of the supreme examples of that independence of the artistic conscience that stands quite outside the collective historical process.”

“Glenn Gould on Bach,” was first broadcast in Canada on April 8, 1962, two years before Gould’s retirement from performing and only two days following his controversial Carnegie Hall concert with the New York Philharmonic, in which Gould’s interpretation of the Brahams D-minor piano concerto was so eccentric that Leonard Bernstein felt compelled to make a disclaimer to the audience. The centerpiece of the recorded broadcast is a performance of Bach’s Cantata BWV 54 featuring the American countertenor Russell Oberlin. “Glenn Gould on Bach” is a fascinating and entertaining half hour–essential viewing for lovers of Baroque and Classical music.

Free Bach Music:

The Open Goldberg Variations: J.S. Bach’s Masterpiece Free to Download

A Big Bach Download: The Complete Organ Works for Free

Glenn Gould Explains the Genius of Johann Sebastian Bach (1962) is a post from: Open Culture. You can follow Open Culture on Facebook, Twitter, Google Plus and by Email.

‘A Baboon of Genius’: Nabokov talks ‘Lolita’ on Fifties TV

Among other things, in recent weeks we have learned that, had Humbert Humbert – the narrator of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita – moved to England, bagged a job with the BBC, and feigned (very much feigned) an interest in pop music… well, what a happy existence he could have led. I can almost picture the old dog presenting Top of the Pops (perhaps even wearing a track-suit and smoking an oversized cigar) surrounded by teenyboppers and smiling ear to ear.

As it was, Nabokov had in mind a more furtive and frustrating existence for his protagonist, who he describes here, in splendid 1950s CBS footage with Lionel Trilling, as a “baboon of genius.” Nabokov himself, shuffling his famous index cards (he insisted upon preparing his answers in advance, and reading them aloud), was in the midst of a very rich vein of form indeed, one that resulted not only in Lolita but also Pnin and Pale Fire. He is bright-eyed, ironical, eccentric, amusing and wholly indifferent to the kind of impression his controversial masterpiece (which has since sold more than fifty million copies) was making to 1950s America.

Mailer Must Die: The ‘Maidstone’ Fight

There are few things sexier in this life than seeing a young, virile Rip Torn go medieval on acclaimed writer, wife-beater and underground filmmaker, Norman Mailer. This may sound like some wondrous fever dream but sometimes magic happens in real life and such an incident not only occurred but was documented in Mailer’s 1970 film, Maidstone. This event was so monumental that already half-whispered legends are born from this moment, including some speculation that Torn was tripping to the gills on acid for two days beforehand, but that’s just the tip.

Artists are mere flesh and blood, too, but with more passion, madness and imagination than the average person, so when they fight, it can quickly turn into a dark, more violent version of Destroy All Monsters. This is exactly what happened behind the scenes on the set of Maidstone, one of three underground films that Mailer directed in the late 60’s. (The other two being Wild 90 and Beyond the Law, with Torn also starring in the latter and the former being written by D.A. Pennebaker) The essential back story is that Mailer changed some key elements from the original script, including an alluded-to brothel sequence. Add in Torn, being the passionate artist that he was (and undoubtedly still is, even if his underground film days are long behind him), some potential chemical and physical exhaustion, all adding up to method acting going one step further.

In the film, Torn’s character, Raoul, the half-brother of famed director and presidential candidate, Norman Kingsley (Mailer), plots an assassination of his politically ambitious and arrogant kin. Torn begins the scene, letting Mailer know only when he clubs him on the head with a hammer. This is no stage magic, though, as they wrestle to the ground, both bleeding for real, with Torn’s coming from a vicious bite on the ear courtesy of Mailer. The tussle is something to behold, with Mailer grunting like an enraged caveman and Torn remaining cool as a cucumber, even saying, “No baby. You trust me?” Mailer pulls a chump move by acting like all is forgiven, only to attack Torn when his defenses are briefly down. But Torn, despite being smaller in size, deftly pins back him down and starts to choke him, when Mailer’s on-screen and real life wife, former-model and actress Beverly Bentley, realizing that the bloodshed was real, starts to scream and freak out, making the Mailer-children brood scream and freak out too.

From there, the battle continues, but with words instead of hammers and fists. Torn is clearly hurt and using words like “fraud” repeatedly, while Mailer tries to he-man it up, coming across like an Ivy League brat playing Hemingway. What’s amazing is, despite all the drama, Torn still manages to one-up Mailer, with one of the highlights being when, off screen, one of the Mailer children says, “don’t fight any more.” It is Rip, not Mailer, who responds, saying “That’s right baby, no fighting. It was just a scene in a Hollywood whorehouse movie. Okay baby? You know it’s okay and your Dad knows it’s okay.” Then he whispers under his breath, looking right at Norman and smiling maniacally, “Up yours.” What’s the best Mailer can come up with? “Adios.”

It would be easier to feel bad for Mailer if he didn’t reek of ego and macho bravado, all in stark contrast to the very earthy and naturally masculine Torn. On top of that, the man was a notorious blowhard with a history of violence against women, including stabbing his second wife Adele Morales. That’s not to say he wasn’t a talented writer and to his credit, the whole reason we are blessed to have this phenomenal fight to enjoy is that he actually included it in the film. Rare moments of slack aside, seeing the young, wild-eyed Torn best Norman Mailer is a borderline-harrowing gift of wonder.

Thankfully, Criterion, as part of their Eclipse series, has recently released not only Maidstone, but also Wild 90 and Beyond the Law as a two-disc set. So now a new generation of fringe film viewers can get a peak into late 60’s underground cinema and see the evolution of one of the greatest working character actors today.

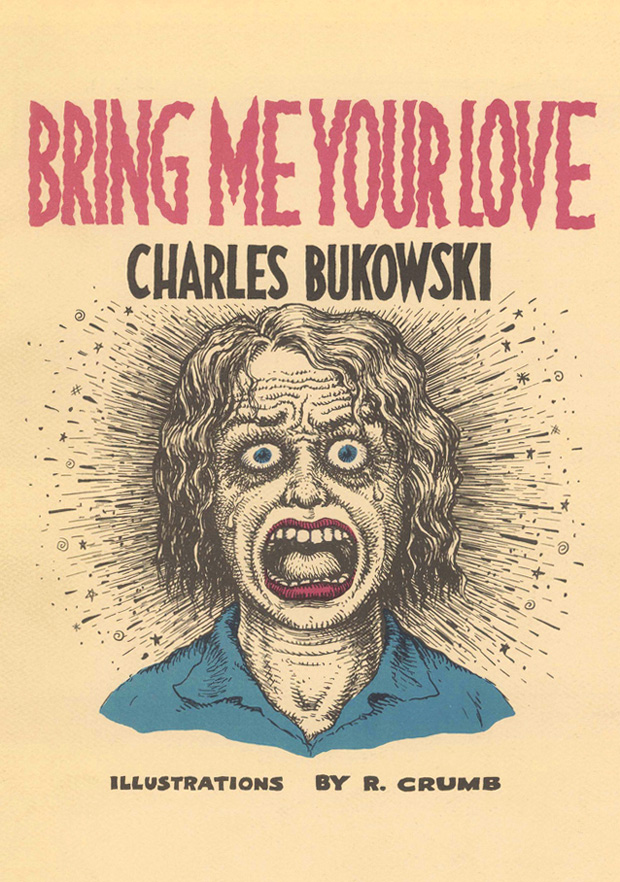

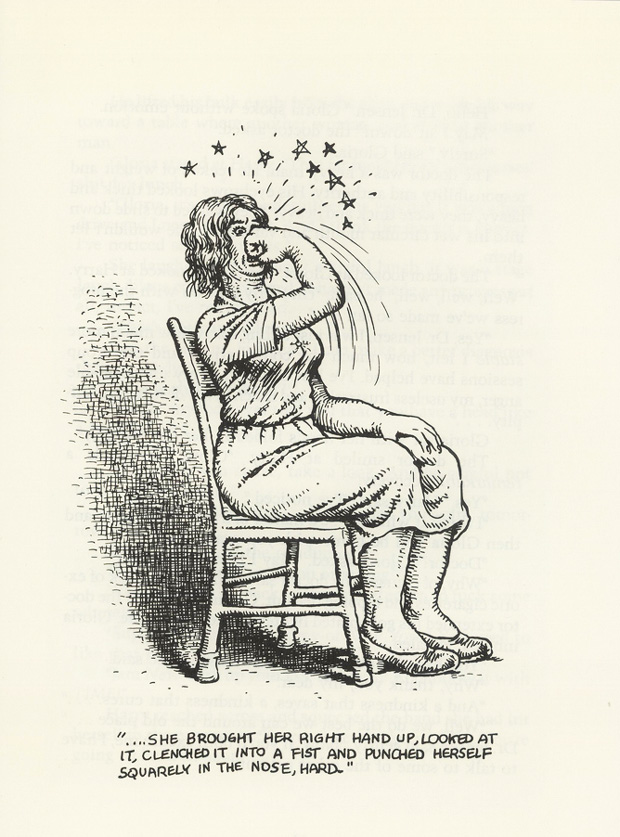

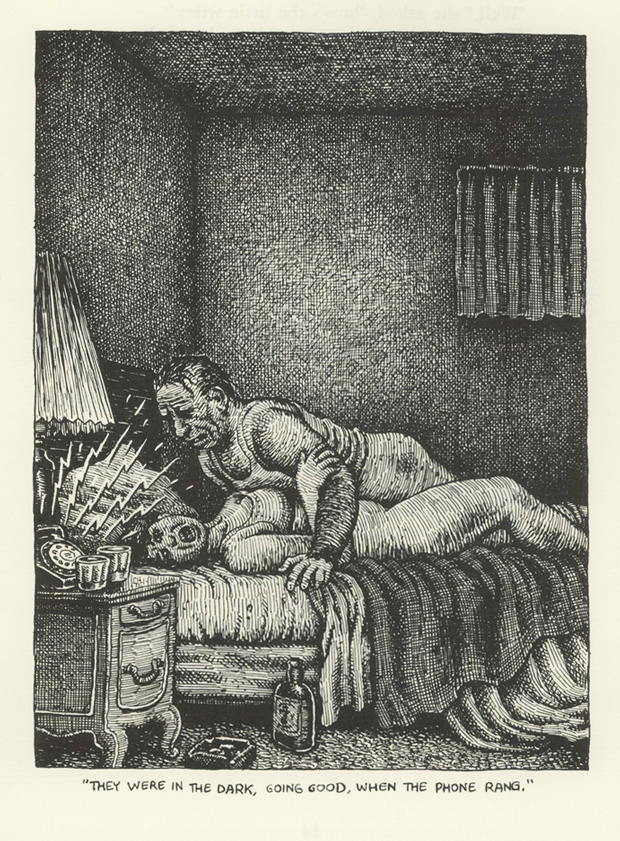

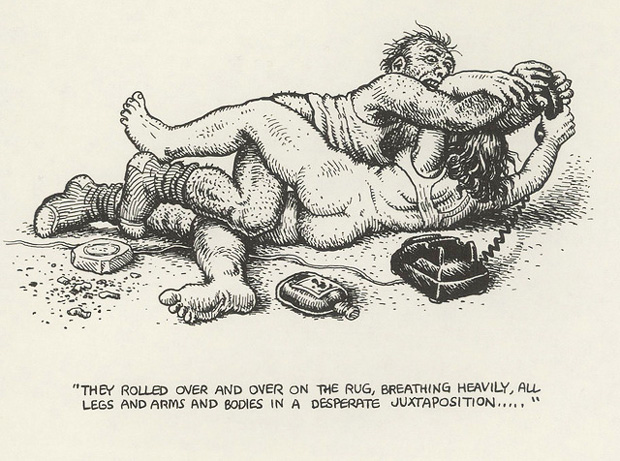

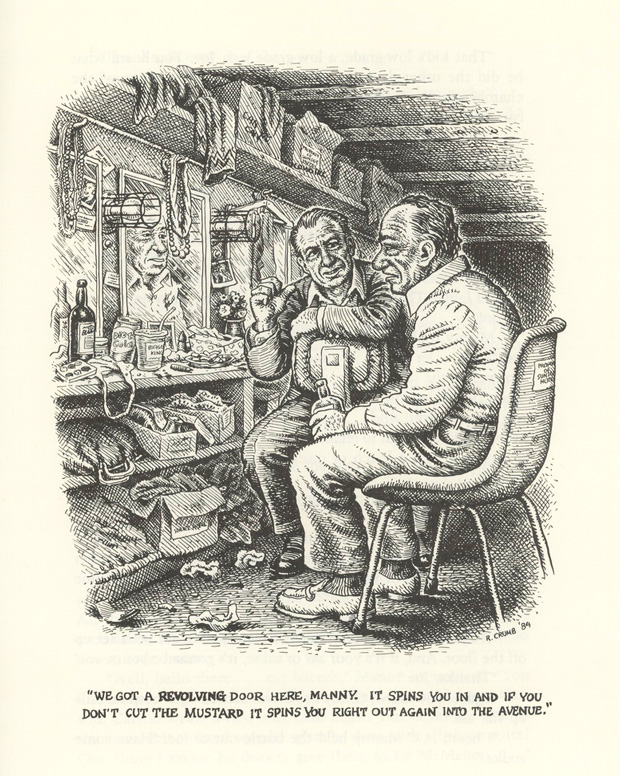

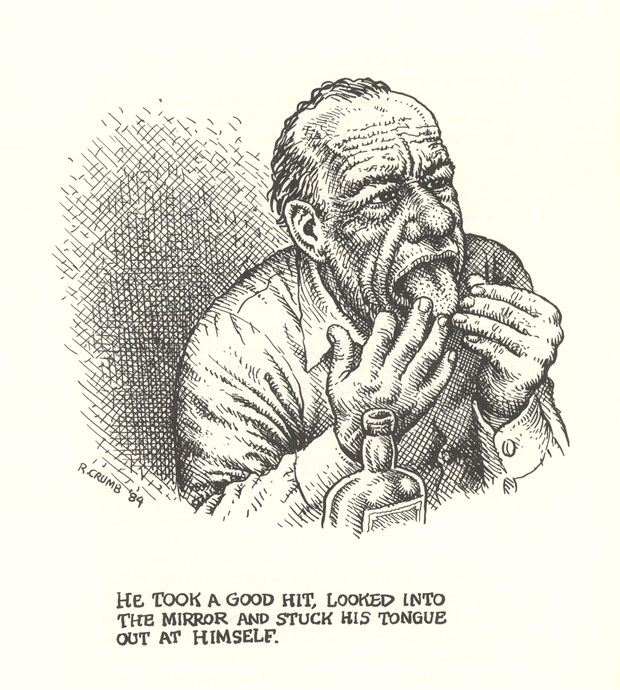

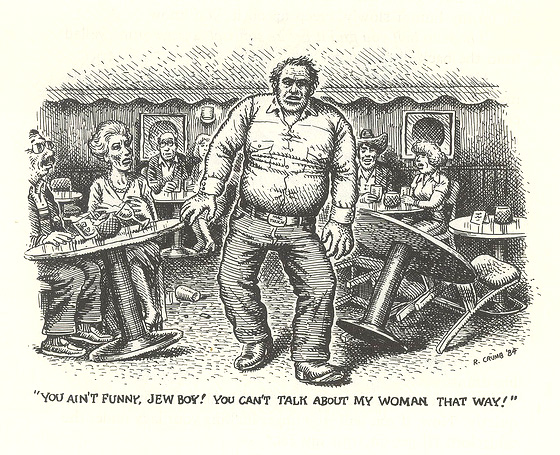

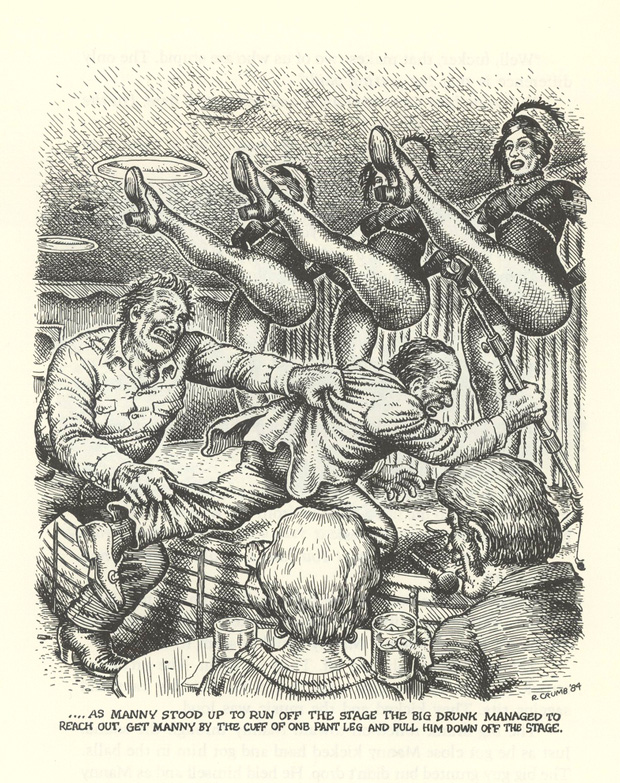

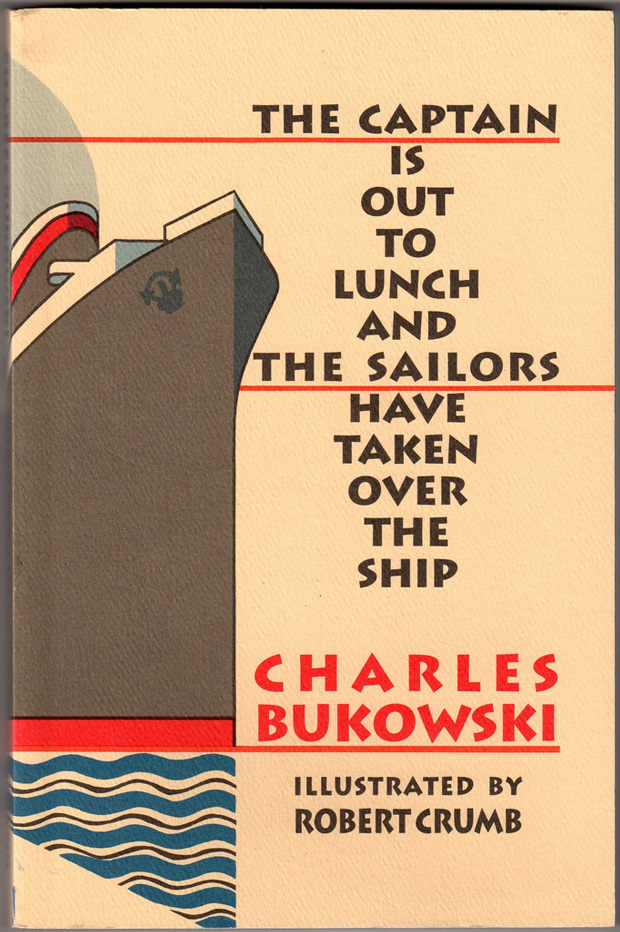

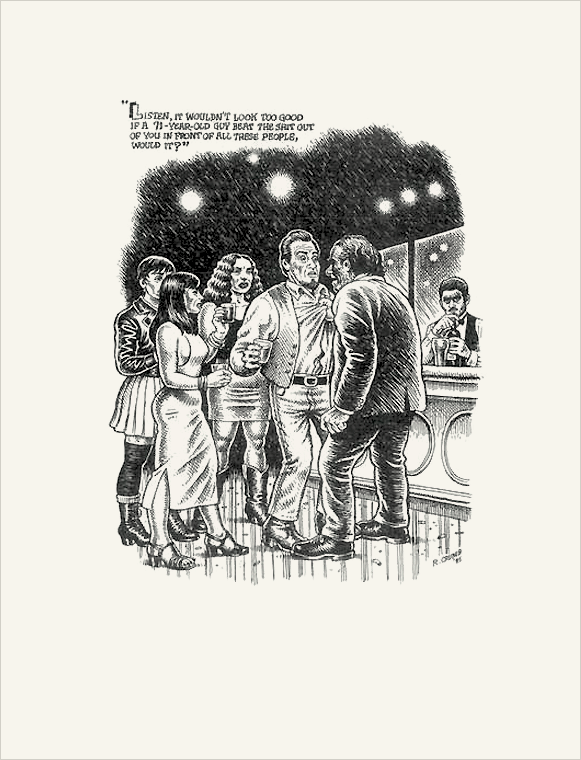

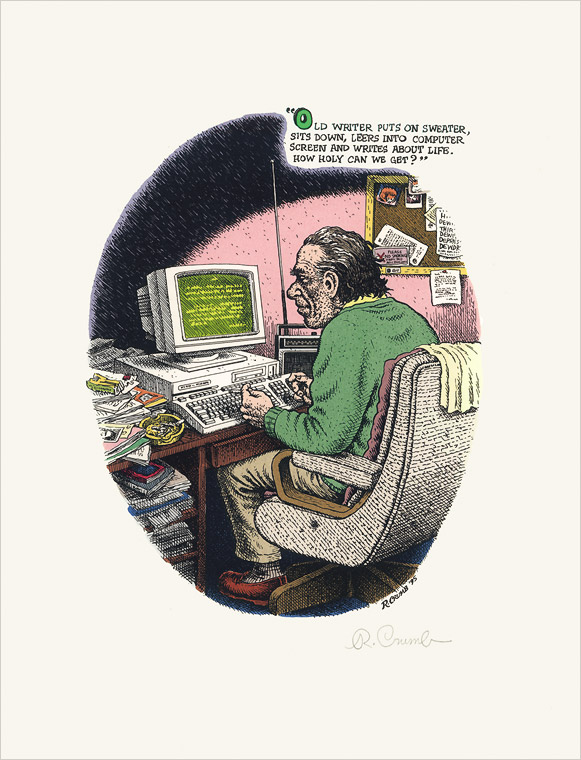

R. Crumb Illustrates Bukowski

Two grand masters of irreverence come together.

In the early 1990s, two titans of the artfully cynical and subversive joined forces in an extraordinary collaboration: Legendary cartoonist and album cover artist R. Crumb illustrated two short books by Charles Bukowski, Bring Me Your Love (public library) and There’s No Business (public library). Crumb’s signature underground comix aesthetic and Bukowski’s commentary on contemporary culture and the human condition by way of his familiar tropes — sex, alcohol, the drudgery of work — coalesce into the kind of fit that makes you wonder why it hadn’t happened sooner.

In 1998, a final posthumous collaboration was released under the title The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship (public library) — an illustrated selection from Buk’s previously unpublished diaries, capturing a year in his life shortly before his death in 1994.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter and people say it’s cool. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter and people say it’s cool. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings takes 450+ hours a month to curate and edit across the different platforms, and remains banner-free. If it brings you any joy and inspiration, please consider a modest donation – it lets me know I'm doing something right.

The Scotch Pronunciation Guide: Brian Cox Teaches You How To Ask Authentically for 40 Scotches

Some Scotch names are fairly straightforward — Glenlivet, Glenfiddich, Laphroaig. Others not so much. I mean, give Bunnahabhain and Caol Ila a try. Well, if you’re a connoisseur struggling to get the pronunciation right, this will serve you well. Esquire has created “The American Man’s Scotch Pronunciation Guide” (though you hardly need to be male to profit from it), which features “esteemed actor and proud Scot” Brian Cox sipping/talking his way through more than 40 brand names. Catch them all here.

via @PartiallyExLife

The Scotch Pronunciation Guide: Brian Cox Teaches You How To Ask Authentically for 40 Scotches is a post from: Open Culture. You can follow Open Culture on Facebook, Twitter, Google Plus and by Email.

The Most Iconic Film Title Sequences of All Time

Today marks the opening of Goldfinger: The Design of an Iconic Film Title, MoMA’s focus installation — in conjunction with the film exhibition 50 Years of Bond — featuring the first film title sequence to enter the museum’s permanent collection. Designed and directed by Robert Brownjohn, the Goldfinger titles are believed to be one of the best examples of title design used to produce a pertinent film component that’s not just a necessary afterthought. As the show’s catalog states, “Brownjohn deployed type in dynamic, abstract forms, in this case illustrating both his mastery of modern graphic design and his ability to apply sophisticated graphic treatment to popular media.”

In honor of Bond’s golden anniversary and a long-standing legacy of outstanding opening credits, we’ve taken a look at the art of the title through the ages. From Saul Bass’ pioneering early work all the way up to the exceedingly clever introduction to nerd dramedy at its best, click through to check out the most iconic film title sequences of all time. Let us know in the comments what designs you’d add to this list!

The Man With the Golden Arm by Saul Bass (1955)

The title sequence that introduced the man that would become one of the greatest graphic designers the world has known was an abstraction of a very taboo subject matter in the mid-50s: the life and times of Frankie Machine, a jazz musician (played by Frank Sinatra) battling a heroin addiction. As controversial as the film itself, Bass chose the arm as the central image of his design.

As one analysis of the sequence states, “the titles for the film feature spiny, cut-out projectiles, vaguely redolent of veins and syringes, that manage to be disconcerting despite the accompaniment of Elmer Bernstein’s rather brassy jazz score. Privileging the director’s credit, the titular ‘golden arm’ (which actually refers to Frankie’s prowess as a card dealer and not the location of his track-marks) appears as a bent and tortured appendage, reaching out for either redemption or a fix.”

Vertigo by Saul Bass (1958)

In describing Bass’ opening credits for Vertigo, Ben Radatz, contributor to Art of the Title, wrote that “there is a threshold in art and design where a work can become so iconic as to transcend its own scope and become a symbol for its medium.” This design did just that. Combining artist John Witney’s pioneering spirographic images — an early example of computer arts — with sensual close-ups of the film’s star, Kim Novak, Bass that frames the film’s premise through evocative-yet-unlikely imagery and Hitchcock’s unique branding eye.

Anatomy of a Murder by Saul Bass (1959)

Using cut-out animation, the Saul Bass legacy continues with what has become his most celebrated film sequence. Collaborating again with director Otto Preminger (The Man with the Golden Arm), this similarly controversial film was one of the first mainstream Hollywood films to address sex and rape in graphic terms.

North by Northwest by Saul Bass (1959)

The last Bass design we’ll feature (we easily could have dedicated this piece to him!), the North by Northwest title sequence opens with lines crisscrossing the screen like railroad tracks. The lines then come to form a different shape: a skyscraper. In large block letters, the film’s title and the names of the featured actors move up and down the screen like elevator cars. Soon after, the lines merge into an actual shot of a building, with a sea of yellow taxis reflected in its façade.

Setting the tone for what’s to come, Bass brilliantly conveys the mood of the film down in a brief but compelling graphic narrative.

Dr. No by Maurice Binder (1962)

The 1960s ushered in a new brand of motion graphic pleasure: the James Bond title sequence. Maurice Binder would design 14 of the Bond films’ iconic intros, but Dr. No was the first, and in it he established the often imitated, never duplicated signature gun barrel sequence.

To Kill A Mockingbird by Stephen Frankfurt (1963)

Stephen Frankfurt’s compelling still life sequence was the inspiration for Kyle Cooper’s haunting snapshot of a serial killer for Fincher’s neo-noir thriller, Se7en. The designer explains his mold-breaking macro masterpiece by saying that “the goal was to find a way to get into the head of a child.” As Cooper would later do with a psychopath.

Note: The only filmic version we could find online is a re-score. This is not the original soundtrack.

Dr. Strangelove by Pablo Ferro (1964)

Would Cuban designer Pablo Ferro ever have guessed that his groundbreaking title sequence for Kubrick’s war satire would go on to inspire the next century’s hipster movement? Geoff McFetridge’s version for Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are kicked off a national obsession shared by everyone from America’s favorite denim brand to corner coffee shops the world over.

Ferro’s full-screen graffiti-like scrawls comprised of thick and thin hand-drawn letters were unlike any movie titles before it. One downside of working with hand drawn type: after the film was released, Ferro notice that one word was misspelled: “base on” instead of “based on.” Whoops.

Goldfinger by Robert Brownjohn (1965)

Set to one of Shirley Bassey’s signature tracks, Goldfinger, Brownjohn’s original opening sequence – as stated by the curator of MoMA’s focus installation – captures the sexual suggestiveness and wry humor of the James Bond mythos. Scenes from the film are projected strategically onto starlet Margaret Nolan, while minimal credit texts balance each shot.

Made in U.S.A. by Jean-Luc Godard (1966)

There’s speculation that Godard designed this font — what went on to become his signature typeface — and also this sequence. A playful, patriotic interpretation that almost reads as propaganda for a French film that is unabashedly commenting on America’s increasing global presence.

Thomas Crown Affair by Pablo Ferro (1968)

A lesser known, but equally iconic design by the Cuban legend Pablo Ferro.

Se7en by Kyle Cooper (1995)

“When I was a kid and I would watch horror movies, the monster didn’t come out until the third act,” designer Kyle Cooper has explained. “I was lucky to watch Se7en early on, and I remember thinking that after I saw it, I wanted to see the killer earlier on… to somehow introduce the killer in the titles. I asked if I could look at all the props and anything that [David] Fincher might have to look at, and there were a couple of prop notebooks that had excessive writing in them, and I thought it would be good to do a tabletop shoot with them and have it be about their preparation, as though it was John Doe’s job to prepare them.”

Catch Me If You Can by Kuntzel + Deygas (2002)

Quite clearly inspired by Saul Bass, Kuntzel + Deygas felt that his real genius was finding an idea and then linking it with the music. In Catch Me If You Can, the action takes place between 1963 and 1969. They designed the characters with ’60s haircuts, clothes, and postures, but the music by John Williams brings a lot more of that sixties feeling. As the designers offered, “try another piece of music and you’ll see it does not fit.”

Napoleon Dynamite by Jared Hess (2004)

(Click the above image to view the video.)

Hands down the most iconic title sequence of the last decade. Brilliant, beautiful, and appropriately bizarre.

I Am Love by Marco Cendron (2010)

IO SONO L’AMORE – Opening titles sequence from POMO on Vimeo.

The Italian designer studied old iconic Milanese shop signs for inspiration. The product of a collaboration with calligraphist Luca Barcellona, the gorgeous white lettering floats above film footage of a bleakly beautiful Milan. Combined with Brooklyn-based House Industries’ Neutraface font, a nod to the severity of the Fascist style that characterizes many Milanese buildings, the contradiction of the Italian city (a major theme in the film) is beautiful represented over Pier Paolo Ferrari‘s imagery.

Enter the Void by Tom Kan (2010)

Set to LFO’s “Freak,” all we’re going to say about this one is: watch it.

The 10 Most Lovable Movie Monsters of All Time

This past Friday marked the theatrical release of Frankenweenie, Tim Burton’s full-length animated adaptation of his 1984 live-action short of the same name (which he was fired from Disney for making). We loved the original (we’re pretty sure we wore that VHS tape right out), so we’ve always had a soft spot for Sparky that hasn’t been the least bit dampened by his, ahem, reanimation. As a side effect (there are always side effects for these kinds of things), the film’s release has had us meditating on some other cute monsters from cinema, so we’ve put together a list of the most lovable movie monsters of all time — according to us, of course. Click through to saw “aww” at some adorably grotesque faces, and if we’ve missed your favorite, be sure to add to our list in the comments!

Sparky in Frankenweenie

If you had a dog as adorable as Sparky, you’d want to resurrect him too. Well, probably every kid whose dog, regardless of cuteness, gets hit by a car wants to resurrect him, but not everyone is as resourceful (or fictional) as Victor. Unlike the original Frankenstein’s monster, there’s no bitterness and revenge against humanity — just a series of hijinks, terrified neighbors, and a pretty adorable love story with a familiar-looking poodle. Aww.

Maurice in Little Monsters

Remember when Howie Mandel and Fred Savage were all the rage? We yearn for the days — well, sort of. Mandel’s Maurice looks scary, but you couldn’t wish for any cooler, goofier monster to take up residence under your bed. After all, every little boy could use a blue-faced buddy in a leather jacket to show him how to take a walk on the wild side.

Sully and Mike in Monsters, Inc.

These two wisecracking blue-collar monsters are pretty impossible not to love. After all, there’s nothing like a monster buddy comedy to warm our human hearts.

Gizmo in Gremlins

Mogwai care is very simple. If you just follow the rules, you’ll get to have this adorable little fellow as your best friend. And he won’t accidentally spawn hundreds of tiny demons that go on a murderous rampage. Plus, how can you resist that little face?

Eli in Let the Right One In

Eli is sort of the outlier on this list — she may be just as cute as Sully or Sparky, but she’s a hell of a lot more dangerous and frightening. That said, the tender love story and Eli’s emotional depth make us love her as much Oskar does. We probably wouldn’t let her come in, though.

Jack Skellington in The Nightmare Before Christmas

Poor Jack. Haven’t we all felt, at one time or another, like a skeletal monster dreaming of but ill-equipped for the sparkly, apple-red things in life? No? Well. Jack is in many ways a tragic figure, well-intentioned but unable to truly comprehend the world he longs for, and we love all tragic figures. Especially those with bat-shaped bow ties wider than their shoulders.

Shrek in Shrek

Well, obviously. This mighty green ogre is maybe the most popular of all lovable monsters — cuddly, good-hearted, and flanked by equally adorable but slightly less monstrous pals to give him a bit of flavor.

Chewbacca in Star Wars

Chewy might technically be an alien, we guess, but look at the guy — he’s huge and hairy and looks like Bigfoot (he was famously inspired by George Lucas’s dog, Indiana) — so he’s a monster by our standards. Though incapable of English, a better co-pilot and first mate there never was.

Harry in Harry and the Hendersons

And now for the actual Bigfoot — sweet, (relatively) gentle Harry. Whom you love even if he eats your fifteenth birthday corsage that you’ve been saving for six! Whole! Months!

Ludo in Labyrinth

Though he looks mighty monstrous and ugly, Ludo is a sweet and playful creature, and somewhat amazingly given his apparently limited intelligence, is one of the few Labyrinth residents who doesn’t bow down to Jareth. Plus he has that awesome rock-summoning ability, which is rather handy in a pinch.

Bollywood Jaws: The most dramatic ending to a film you’re ever going to see. Ever

Politically Incorrect Advice to the Young from William S. Burroughs, Autotuned

“Any old soul is worth saving at least to a priest, but not every soul is worth buying.”

It is in the tradition of every culture that its cultural icons would impart words of wisdom on its young. In ours, those have come from celebrated minds like E. O. Wilson’s advice to young scientists, Neil Gaiman’s advice to young artists, Jacqueline Novogratz’s advice to young graduates, and Christopher Hitchens’s advice to young contrarians. Joining them is William S. Burroughs with this deliciously autotuned take on his famous, uncensored, and at times questionable advice to the young — which, if anything, underscores the importance of knowing when to and when not to take advice.

It is in the tradition of every culture that its cultural icons would impart words of wisdom on its young. In ours, those have come from celebrated minds like E. O. Wilson’s advice to young scientists, Neil Gaiman’s advice to young artists, Jacqueline Novogratz’s advice to young graduates, and Christopher Hitchens’s advice to young contrarians. Joining them is William S. Burroughs with this deliciously autotuned take on his famous, uncensored, and at times questionable advice to the young — which, if anything, underscores the importance of knowing when to and when not to take advice.

People often ask me if I have any words of advice for young people.

Well… here are a few simple admonitions for young and old:Never interfere in a boy-and-girl fight.

Beware of whores who say they don’t want money. The hell they don’t. What they mean is they want MORE MONEY, much more.

If you’re doing business with a religious son of a bitch, get it in writing. His word isn’t worth shit, not with the good Lord telling him how to fuck you on the deal.

Avoid fuck-ups. You all know the type. Anything they have anything to do with, no matter how good it sounds, turns into a disaster.Do not offer sympathy to the mentally ill. Tell them firmly, ‘I am not paid to listen to this drivel. You are a terminal fool.’

Now some of you may encounter the devil’s bargain if you get that far. Any old soul is worth saving at least to a priest, but not every soul is worth buying. So you can take the offer as a compliment. They charge the easy ones first, you know, like money, all the money there is. But who wants to be the richest guy in some cemetery? Not much to spend it on, eh, Gramps? Getting too old to cut the mustard. Have you forgotten something, Gramps? In order to feel something, you have to be there. You have to be 18. You’re not 18, you are 78. Old fool sold his soul for a strap-on.

How about an honorable bargain? ‘You always wanted to become a doctor. Now’s your chance. Why, you could have become a great healer and benefit humanity. What’s wrong with that?’ Just about everything. There are no honorable bargains involving exchange of qualitative merchandise like souls. Just quantitative merchandise like time and money. So piss off, Satan, and don’t take me for dumber than I look. As an old junk pusher told me, ‘Watch whose money you pick up.’

↬ Ben Kay; image by Christiaan Tonnis

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter and people say it’s cool. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter and people say it’s cool. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings takes 450+ hours a month to curate and edit across the different platforms, and remains banner-free. If it brings you any joy and inspiration, please consider a modest donation – it lets me know I'm doing something right.

Death By Subtitle: How Extravagantly Fallacious Subtitles Are Ruining Books

1959: The Year Everything Changed

Habit: Why We Do What We Do In Life

Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World

And now there’s Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How The World Become Modern, a book which, while very good, doesn’t live up to its subtitle. None of these books do. They can’t. Their subtitles are overly ambitious, promising that everything the reader has ever wondered about will be explicated in grand, enriching, yet academic detail over the course of the next 300 pages. Except this doesn’t happen and reader disappointment ensues. These books are all overpowered by their subtitles.

Greenblatt’s The Swerve is the history of a Latin poem, On the Nature of Things by Lucretius, which was lost ages ago and found in 1417. While Greenblatt’s love for this poem is clear and while he extols its greatness, he never comes close to explaining how the world becomes modern.

There are a few half-hearted attempts to justify the subtitle and a Malcolm Gladwell-esque idea that in history there are swerves, moments where everything suddenly shifts. (The key to having a Macolm Gladwell-esque idea involves capitalizing a noun then making it seem extremely important; luckily, Greenblatt has the dignity to avoid random noun capitalization.) Really, though, this book is the wonderfully well-researched history of Lucretius’s poem. It doesn’t have a lot to do with the entire world or momentous modernity. But if you’ve been keeping up with publishing trends, you probably already knew that.

There’s a tendency in publishing today to affix grandiose subtitles to every non-fiction book that exists. The formula goes a little something like this:

“Cool Phrase [colon] Promise that book will A.) Change Your Life, B.) Show How America Changed, or C.) Explain Everything.”

Here are some more examples:

The Devil in the White City: A Saga of Magic and Murder at the Fair that Changed America (2004)

The Eighty-Dollar Champion: Snowman, the Horse That Inspired a Nation (2012)

Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work, and Learn (2012)

Subtitle grandiosity is a relatively new thing, meant to make books obvious so they can be easily pitched and marketed. There’s a logic to it. Theoretically, subtitles should make it easier for readers to select books. Instead of having to skim an article or book jacket flap, all we have to do is read the subtitle. Supposedly, then, we’ll know what the book is about. However, these subtitles are ridiculously misleading. For instance, Greenblatt’s book isn’t about the entire world. It’s about a single poem. The subtitle misrepresents the book.

The same way snazzy online article titles often don’t describe the articles they’re attached to, book subtitles don’t actually tell you anything about the book. They’re attention grabbers, nothing more. These subtitles are like annoying, dweeby, failed superheroes who wave their arms and scream at us, “Look at me, please! I can do anything you want! Please pay attention over here!”

And even when they’re not extravagantly fallacious, these grandiose subtitles become pompous after analyzing great book titles from the past.

Did Rachel Carson need a subtitle so it’d be easier for readers to understand her? Should George Orwell have tossed a couple of colons into the titles of his works? Would subtitles typical of today have improved these fine writers’ books or made them worse? Let’s take a look by using the subtitle formula on some non-fiction classics.

Silent Spring: How Humans Are Killing Mother Nature And Why It’s Too Late To Stop It

Homage to Catalonia: Life, Love, Death, and Politics During the Spanish Civil War, Which Changed The World

This Boy’s Life: The Inspiring Memoir About Growing Up and Overcoming an Abusive Childhood in the Down-and-Out Northwest

Alfred Kazin’s Journals: The Thoughts and Feelings of a Man Who Understood America Better than Anyone Else Ever

So honestly?

All those books sound bad.

Titles affect how we read and enjoy books. They’re the first words we encounter, even before the author’s note, introduction, or prologue. And if we wouldn’t accept such stupidity and silliness inside books, if reviewers would chastise Greenblatt for making grandiose claims in his actual text, why is it okay to do so on the dust jacket?

An anecdote: A poet once said that the final poem for a book of poetry was the title. This is because titles are part of books’ overall aesthetics. They should provide a sense of unity and honor the actual text. Authors and agents have an obligation to produce the best books possible and having such moronic and misleading subtitles hurts books in the long run. The false promises, pomposity, and silliness of these subtitles erode the reader’s trust and are insulting, as though we’ll only buy books about How America Changed Forever or How Our Lives Will Never Be the Same Again. Intelligent, enjoyable works like Greenblatt’s The Swerve and Kaplan’s 1959 get turned into bloviations, marketed to us using the same claims as self-help books and other charlatan prose.

While this ridiculous subtitling is usually a decision made by editors and marketers who simply want to increase sales—The Swerve, which spent weeks on the NYT bestseller list, is doing pretty good for a book that’s the history of a Latin poem—there needs to be some accountability. There needs to somebody at the publishing houses who’s got a modicum of modesty and after reading the book says, “Maybe this subtitle is a bit BS, even for us.”

Hopefully in the non-fiction mentioned above, the subtitles were tacked on at the end, once the books had been already written. However, there is the worry that, in this subtitle-crazy culture, authors will now write with grandiose subtitles in mind. They’ll feel obligated by commercial pressures to write books about Changing Your Life and about America! and about the History of the Entire World from Neanderthals to Jesus to George Jetson.

Instead of writing a quiet, moving study of a man and museum like Lawrence Weschler did in Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonders or instead of providing incisive insights into the legal system like Janet Malcolm did with The Crime of Sheila McGough, authors will feel pressured to write books that explain America, your life, the world, and everything that’s ever happened.

The long-term worry is that talented writers will alter their subject matter and approach, forcing themselves to make silly claims and absurd overstatements as part of an attempt to make their books more saleable. Research will be jerryrigged to lead to some tedious and unnecessary grand conclusions. Lots of nouns will become capitalized. It will be the Malcolm Gladwell-ing of American non-fiction.

So while the occasional subtitle can be fun and helpful, the subtitle glut we’re experiencing now is bad for books. And this isn’t even getting into the super-long subtitles, like Moby Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them, or the fact that now lots of novels have silly subtitle-ish qualifiers, so there’s Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War and Two Women: A Novel of Friendship.

While it’s fun to imagine parodies (In Cold Blood: A Really Violent Incident Involving Shotguns and a Nice Family Who All Got Got, Which Happened in the Back Country Some Time Ago and the Following Story Was Later Turned Into a Biopic Centered Around the Idea That One of the Killers Sort of Fell in Love with the Author, Who Ended Up Becoming an Immodest Pill Swallower and Famously Wrote, “I’m an alcoholic. I’m a drug addict. I’m homosexual. I’m a genius,” Thus Changing America Forever), it’s all a lot to take. So for the next couple months-ish let’s give ourselves a break and declare a moratorium on subtitles, alright?

***

Alex Kalamaroff is 25 years old. He lives in Cambridge and works for Boston Public Schools.