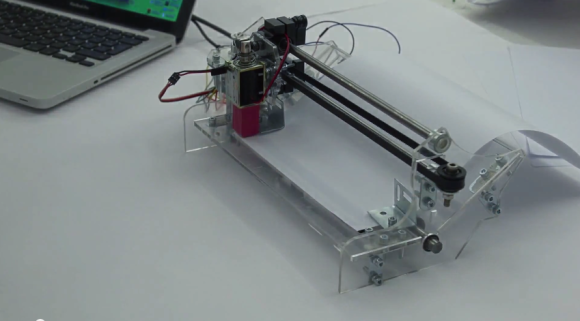

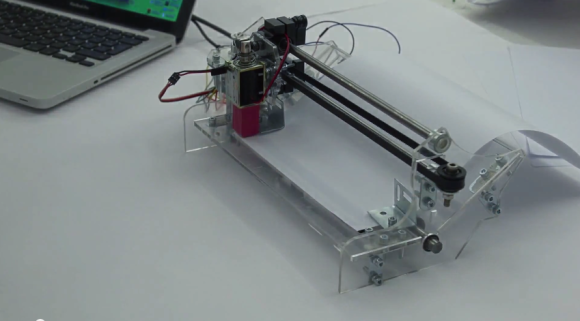

From a distance, it looks like the bare bones of a regular inkjet printer, but it’s not. Instead of an ink-head it features a needle — It’s kind of like a dot-matrix (hole-matrix?) printer.

From a distance, it looks like the bare bones of a regular inkjet printer, but it’s not. Instead of an ink-head it features a needle — It’s kind of like a dot-matrix (hole-matrix?) printer.

Gifs have become a fixture of the web, transformed Buzzfeed into a major media entity, and brought countless millions of hours of joy to bored office drones the world over. There’s a gif search engine and a service that will turn these little moments of web zen into IRL animated pictures.

So why aren’t these miniature animations used more widely for practical purposes? Do any ecommerce sites use animated gifs to show off the unique features of a product? How about replacing turgid instructional guides with gif-tastic help pages? Animated images are a perfect midpoint between static images and full on video content, but are rarely used for productive purposes, with a few exceptions.

DIY.org, a kid friendly site that aims to transform little video gamers into latter day scouts uses the art form to highlight the physicality of their merit badges:

This simple animation shows off the unique feature of an Medieval book that can be read six different ways in three seconds while a highly produced video might take thirty seconds to do the same.

Despite their obvious utility, these catchy little cartoons are relegated to cat pics and epic fails. Why? Are they prematurely dismissed as low brow? Does the larger file size make them a poor fit for an increasingly mobile web? Is the technical challenge of creating them too high?

The question is: How well can this mesh network see you?

How accurately can it geo-locate and track the movements of your phone, laptop, or any other wireless device by its MAC address (its “media access control address”—nothing to do with Macintosh—which is analogous to a device’s thumbprint)? Can the network send that information to a database, allowing the SPD to reconstruct who was where at any given time, on any given day, without a warrant? Can the network see you now?

The SPD declined to answer more than a dozen questions from The Stranger, including whether the network is operational, who has access to its data, what it might be used for, and whether the SPD has used it (or intends to use it) to geo-locate people’s devices via their MAC addresses or other identifiers.

Google no longer understands how its “deep learning” decision-making computer systems have made themselves so good at recognizing things in photos.

This means the internet giant may need fewer experts in future as it can instead rely on its semi-autonomous, semi-smart machines to solve problems all on their own.

The claims were made at the Machine Learning Conference in San Francisco on Friday by Google software engineer Quoc V. Le in a talk in which he outlined some of the ways the content-slurper is putting “deep learning” systems to work.

"Deep learning" involves large clusters of computers ingesting and automatically classifying data, such as pictures. Google uses the technology for services like Android voice-controlled search, image recognition, and Google translate, among others. […]

What stunned Quoc V. Le is that the machine has learned to pick out features in things like paper shredders that people can’t easily spot – you’ve seen one shredder, you’ve seen them all, practically. But not so for Google’s monster.

Learning “how to engineer features to recognize that that’s a shredder – that’s very complicated,” he explained. “I spent a lot of thoughts on it and couldn’t do it.” […]

This means that for some things, Google researchers can no longer explain exactly how the system has learned to spot certain objects, because the programming appears to think independently from its creators, and its complex cognitive processes are inscrutable. This “thinking” is within an extremely narrow remit, but it is demonstrably effective and independently verifiable.

”

SUBMISSION: Torpedo typewriter organized neatly

I interviewed novelist Sol Yurick back in March 2009. Rather than publish the interview on BLDGBLOG as I should have, however, I thought I'd try to find a place for it elsewhere, and began pitching it to a few design magazines. Yurick, after all, was the author of The Warriors—later turned into the cult classic film of the same name, in which New York City is transformed into a ruined staging ground for elaborately costumed gangs—and he was a familiar enough figure amidst a particular crowd of underground readers and independent press aficionados, those of us who might gravitate more toward Autonomedia pamphlets, for example, where you'd find Yurick's strange and prescient Metatron: The Recording Angel, than anything on the bestseller list.

Looked at one way, The Warriors tells the story of a city gone out of control, become feral, taken over by criminal gangs and faceless police organizations, its infrastructure half-abandoned or, at the very least, fallen, limping into a state of quasi-Piranesian decay. The everyday lives of its residents whirl on, while these cartoon-like groups of armed militants spiral toward violence and disaster. Yurick was thus an urban author, I thought, suitable for urban and architectural publications, his insights on cities far more useful than your average TED Talk and about one ten-thousandth as exposed.

In the interview, published for the first time below, Yurick freely discussed the back-story for The Warriors, which was the question that had motivated me to contact him in the first place. But he also drifted into his interests in the global financial system, which, at that point in time, was melting down through a domino game of bad mortgages and Ponzi schemes, and he went on to offer an even more dizzying perspective on Dante's The Divine Comedy. Dante, in Yurick's unexpected retelling, had actually written a series of concentric financial allegories, tales of monetary wizardry starring lost, beautiful souls searching for one another amongst the impenetrable mathematics of paradise.

Along the way, we touched on Mexican drug cartels, the Trojan War, the United Nations, and a handful of forthcoming books that Yurick was still, he claimed, energetically working on at the time.

Image from Paper Tiger, via Sheepshead Bites

Image from Paper Tiger, via Sheepshead Bites

Alas, I pitched the wrong magazines and, soon thereafter, hit the road for a long period of travel and work; the interview simply disappeared into my hard drive and years went by. Then, worst of all, Yurick passed away in January of this year.

The New York Times described him as "a writer whose best-known work, the 1965 novel The Warriors, recast an ancient Greek battle as a tale of warring New York street gangs and earned a cult following in print, on film and eventually in a video game." Writing for The Nation, Samuel Fromartz specifically referred to several "out-of-the-blue interview requests" that had popped up in Yurick's latter years, asking him about, yes, The Warriors. As Fromartz writes, "despite the delight he got in its cult status, it did not mean a lot more to him" than his other books, The Warriors being simply one project among many.

And so this interview sat, unpublished, till I came across it again in my files recently and I thought I'd give it a second life online. It's a fascinating discussion with an aging writer who unhesitatingly looked back at a long career of writing both fiction and political analysis, a life of deep reading and even a few eye-poppingly abstract interpretations of Dante.

What follows is the final edit of our conversation. Yurick was an engaged and pointed conversationalist, and, while I was obviously just another out-of-the-blue interviewer curious about the broken city of The Warriors, I hope this text does justice to his creative and sharp vision of the world.

So this is for Sol Yurick, 1925-2013.

* * *BLDGBLOG: I’d love to start with the most basic question of all, which is to ask about the back-story behind The Warriors. What motivated you to write it when you did?

Sol Yurick: Well, initially it started off when I was talking about some ideas with a friend in college. I’d just finished reading Xenophon and the concept popped into my head. This was the early 1940s.

Then, later, maybe in the 1950s, I read Outlaws of the Marsh, and the combination of ritual and violence in Outlaws of the Marsh just took my breath away. Those things mixed—Xenophon, ritual violence, Outlaws of the Marsh—and, on top of all that, I had already been working on a novel of my own. I was trying to get it published and it kept getting rejected—maybe 37 times?

BLDGBLOG: Wow.

Yurick: To move on to the next step, I wrote The Warriors. I did it in about three weeks. By this time, a lot of these ideas had matured. I’d been thinking about the whole question of gangs. First of all, the youth gangs at that point in time, running into the 1950s and ’60s, had no economic basis whatsoever. They mostly came from poverty-stricken families. You remember the film Rebel Without a Cause, right? That kind of stuff. It was viewed as kind of a national problem.

However, there were also gangs that came out of the suburbs—gangs nobody had ever heard about. No sociologist had wrote about this. In fact, I was big on sociology at the time, especially the works of Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, the founders of modern sociology. I wanted to write about stuff that approached reality—that was based in social reality—and that was not bound by a lot of the clichés or conventions of fiction as I knew it. I wanted to deal with a different stratum of society, something that wasn’t getting the attention it deserved in fiction at the time.

By the time I was actually writing the book, though, the whole 1960s had already started, and I eventually had a different take on it. In the book, it’s really about making a revolution, not just a criminal gang taking over the city. After all, it takes place on July 4th! But, in the book, that holiday is like a slap in the face for my characters—at least that’s the vision of the gang leader, looking at all the things that keep these people down. It’s Independence Day—but independence for whom? Independence from what?

Since that time, I’ve thought an awful lot about gangs and I began to see them in a very different way, as almost a biological formation. People make gangs—men and women, what have you. Cliques, clans, whatever you want to call it. There seems to be a big impulse there, something deeply social and political, but also maybe something biological.

I’d been thinking and meditating on this whole thing—this whole problem of the gang and what makes it. The interesting thing about gangs, as I wrote about them at that point in time, and as I mentioned, is that they had no economic basis. That all began to change during the period of the late 1950s and early 1960s, especially in relation to Vietnam, when more and more heroin began to be imported into the United States—a chunk of that coming through the good offices of the CIA. So, especially looking at the drug cartels in Mexico today, but also looking at this phenomenon of organized crime all over the world, the more you see that gangs are essentially capitalists. Within that system, they organize themselves: they have hierarchical principles and their leadership gets the best of everything. The lower strata are just the soldiers who risk their lives and don’t make out too well.

Look at the other gangs and mafia in 'Ndrangheta, Calabria, the Camorra, the Japanese gangs, the Chinese triads, the Bulgarian gangs, the Russian gangs, all of that. It’s a business. Essentially, there are connections between these phenomena and corporate capitalism and politics, one way or another. On some level, there are always connections to something else—some other group, level, or economic phenomenon. In fact, no phenomenon, whether we’re talking physics or chemistry or what have you is totally isolated. Total isolation, or the making of discrete sets, is really an intellectual concept. No social formation is isolated in and of itself. It just isn’t.

What’s interesting is that, wherever you go, the gangs develop their own cultures. What makes them alike is generally their structures—their hierarchical structures—and the necessity for their leadership, whether it’s male or female, to exhibit charisma, machismo or machisma. And I don't care whether you see this in corporations, which are supposedly rational entities but that, really, are not—because, otherwise, why would people talk about the “culture” of a corporation as something that can drive it into bankruptcy or make it successful? And how is that culture different from another corporation? So, in gangs and corporations both, we’re seeing a kind of driven necessity—maybe biological—to make and sustain a culture. But each culture is different.

Structurally, things look the same, but, culturally, things look different. That fascinates me.

Also, I grew up in a Communist household. Starting in the 1960s, I went back to reading Marx. In the back of my mind, though, there were aspects of Marx that seemed inadequate as a theory. It was very Western-centered; the number of classical and historical references in all of Marx’s work was just overwhelming to me. For all of his references, it felt limited. Then, as well, I began to think more in terms of neo-Darwinism. I don’t mean social Darwinism. Leftists and liberals deny the question of human nature, but what if it’s true? So that also became a consideration in my thinking—mixing the two: Marx and Darwin.

All of that was part of the back-story for The Warriors.

BLDGBLOG: Before we move on to other topics, I think it’s interesting how much the built landscape of New York has changed since you wrote The Warriors. I’m curious, if you were to update the story of Xenophon again and rewrite The Warriors today, if there is a different location you might choose, whether that's a different city or a different part of New York.

Yurick: Well, I would make it global, for one thing. And I would try to bring into it questions of finance—things like that. I’m not sure, though; I haven’t thought of that. Yes, there was a political and economic connection to Xenophon, and to Xenophon’s story—essentially, these gang members were mercenaries, and they were also a surplus population pushed to the edge of society. They were, after all, kids. And they were revolutionaries, not just street criminals. But I don’t know exactly how I’d handle it today.

Again, the whole question of making a revolution in the old way—it’s a tricky one. From my way of thinking, what happened in the Russian Revolution is: you had an uprising. People were discontented and what have you. Then a moment of opportunity came along, when it was a complete breakdown, and, at that point, Lenin stepped in. It was purely opportunistic. There was nothing decent in his move. There it was. It happened. Boom. He took advantage.

BLDGBLOG: In your book-length essay Metatron: The Recording Angel, you combine so many of these interests—everything from finance to electronic writing, looking ahead to what we now call the internet, and so on. I’m curious if we could talk a little bit about how Metatron came about, what you were seeking to do with that book, and where you might take its research today?

Yurick: When I wrote that, it was still early on. Computers were not universally around. I had a friend who was a computer expert—he had become an expert in the 1950s—so I was introduced to computers and the idea long before there were PCs or anything like that. I knew, when I saw stuff that would later become the internet—exchanges between scientists who had access to this kind of stuff—I knew I was looking at a different world. I began to see signs that this was going to become a big phenomenon, one of information and the effects of information. And again, this was before anybody had home computers.

Then computers began to come in, bit by bit. We’re talking maybe 1979. What happened then was that I got tied up with an organization trying to promote the use of satellites for global education. By this time, though, having been through the 1960s and 70s, I was telling them that this was just not going to happen. You’re not going to get money for this kind of thing; they’re going to use satellites for any other purpose for the most part, maybe military purposes, maybe propagandistic purposes, certainly for telecommunications.

But I went down to Washington with these people a couple of times, and we sat in on the committee hearings. Then I wrote a piece—an essay—to sort of introduce our organization. I forget when it was—maybe 1979 or 1978—but Jimmy Carter was coming to the UN and, because of the connections of several people in this organization, somebody got my essay to Jimmy Carter’s people. He almost incorporated a piece of it into his speech at the UN!

That didn’t happen, of course, so I decided I would submit it to this little publishing house, and they asked me to expand on it. I did that, and that was Metatron.

So my mind was ranging over all these things. I was trying to think of what the effect was going to be of computers and networks and satellites, trying to anticipate a lot of side effects. There was a lot I didn’t foresee, but there were some things I saw beginning to happen—that then, in fact, did happen maybe ten years later. Things like running factory farm machines by satellite and, now, running drones over Afghanistan from a place in Nevada. Things like that.

Anyway, having been getting more and more involved in many areas, while at the same time trying to find a basis for writing my fiction from new perspectives, became very destabilizing. Because most writers—most people—just stop growing at a certain point. They stop taking in more stuff because it gets in the way of their writing. But the opposite was happening. For instance, with The Warriors, I was able to make an outline chart of how the themes would develop. I could coordinate everything: what happened to the clothing, what happened at a certain time of day, and so forth and so on. Interestingly, the form of the chart I borrowed from a business model called program evaluation. It was a review technique. So I could do this thing and it came easy.

But when I tried to do it with The Bag, it didn’t work. I had such a hard time doing The Bag. The chart began to expand and expand till it was about ten feet long; I had different colors on it; it just didn’t work right. But I was learning so much.

Anyway, at certain points you’ve got to say enough. I forget which writer said this: “You don't finish the work you abandon.”

BLDGBLOG: The financial aspects of your work are very interesting here, as well.

Yurick: Do you mean the economic?

BLDGBLOG: Well, I mean “financial” more specifically to refer to the system of writings, agreements, valuations, and so forth that constitute the world of international finance—which, if you take a very basic, material view of things, is just people writing. It’s numbers and spreadsheets, stock prices, contracts, and slips of paper, licenses and patents—its own sort of literature. You imply as much, in Metatron, with its titular reference to the archangel of writing.

Yurick: OK, yes. You know, I’ve been saying for years to people that this is coming, this moment [the financial crisis of 2007-2009], and it’s happening now. I read the newspaper and I see it: these people manufacturing money out of their imaginations. Sooner or later the bubble has got to burst, and it’s bursting.

In a certain sense, what’s taken place—what’s taking place now—is a series of mistakes. In other words, you don’t hire the people who caused the problem in the first place to try to rectify it, yet that’s what’s happening. It’s very interesting, I think, to look at this in terms of the criminal elements that we discussed—the gangs—and to see that what they do is done through extortion, prostitution, the selling of illegal things, illegal commodities, and what have you. They accumulate money and they launder it. But this also happens at the very top levels of finance: they imagine money and then they objectify it in terms of mansions and things like that.

When you’re dealing with this kind of stuff, you’re dealing with fiction—and when you’re dealing with fiction, you’re in my realm.

BLDGBLOG: The financial world that’s been created in the last decade or so often just seems like a dream world of overlapping fictions—of Ponzi schemes and collateralized agreements that no one can follow. It’s as is people are just telling each other stories, but the characters are mutual funds, and, rather than words, they’re written in numbers. To paraphrase Arthur C. Clarke, it’s as if sufficiently advanced financial transactions have become indistinguishable from magic.

Yurick: A long time ago, I started to write a book in which I invented a planet, and the planet was ultimately nothing but finance. I called it Malaputa. Do you know Jonathan Swift’s work at all? One of the trips Gulliver takes is to an island called Laputa, which really means, in Latin, the whore or the hole. There he encounters nothing but intellectuals building the most astonishing mental structures and doing the stupidest things imaginable. Now, Malaputa would be the evil whore.

So the planet I began to invent was a world that interpenetrates ours and it works by the rules of our world, but it’s not visible. Ultimately, it resides in the financial system in which, as you get to the center of it, its mass and velocity keep on increasing potentially. It’s the movement, ultimately, of symbols.

I realized, at a certain point, that what I was also talking about was, in a sense, The Divine Comedy. The descent into the Inferno, if you remember, is in the form of a cone—the inside of a cone. The ascent to the top of Mount Purgatory is also a cone, but you climb on the outside. Then, to move on to heaven, you have a series of concentric circles, at the center of which is the ultimate paradise, which is where God resides. The circles are spinning, but they’re spinning in an odd way. If you’re at the center of a spinning circle, you’re barely moving around. If you’re on the outside, you’re moving with great velocity.

In this case, Dante tells us that the center of the circle spins with the greatest velocity, and the further out you get away from it, the slower it moves. What does finance have to do with this? The woman who Dante idolized—Beatrice—was a banker’s daughter. You could say his interest in her was partly financial, pursued through these circles and cones of symbols. Anyway, that’s the architecture of The Divine Comedy that I was getting at.

From this point—as all of this was going into the stuff I’m writing now—I began to meditate on the question of surplus labor value. Which, as Marx said, is the unpaid part of what a worker doesn’t get, the part that the owner—the owner of the means of production—expropriates.

BLDGBLOG: The Malaputa idea was for an entire standalone novel, or it’s something that you’re now including in your current work?

Yurick: It was originally going to be its own book, but I’m going to change that. I’ll incorporate it; I’ll reinvent it.

I wrote a piece a long time ago for—I forget the name of the magazine. It was on the question of the information revolution, the dimensions of which were not yet clear at that point. I think it was the mid-1980s. I was talking about, even at that point in time, the speed of the transactions, and the infinitesimally small space in which transactions occur—against the space that you have to traverse either by foot or other means, like to the market village or the shopping mall or the warehouse floor.

In other words, I’m saying that finance has a space—it has an architecture. You might want to transfer billions of dollars from one country to another, but both are accounts in one computer space. What you’re doing might have enormous effects on the real world—the world of humans and geography—but what you’ve done is move it a fraction of an inch, at an enormous speed, with an enormous velocity and mass. And that has real effects thousands of miles away.

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious if you see other future developments of these works, or if there’s something new you’re working on at the moment.

Yurick: Yes—I’m working on two things that may intersect. One is a kind of biography that I call Revenge. What I realized, in a certain way—partly because I grew up in the Depression under bad circumstances, and now I see those same circumstances coming back again—I realized at a certain point that my novels Fertig and The Bag were revenge novels. That was a theme that was not clearly in my mind at the time, but that came into my consciousness relatively recently.

Revenge begins with trying to pick a starting point—to impose a starting point—because wherever you begin, there is no ultimate beginning. Someone did something to someone else, in reaction to something that came before that, and so on and so forth. You start in the middle of things, and choose a starting point. It’s like a lot of the things we say about The Iliad, for instance. They start in the middle of things, in medias res.

There was an essay I wrote for The Nation on Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, in which I panned the novel. But what I realized, even at the time I was writing it, was that, in a certain way, the story in that book—the true story it was based on—wasn’t just a random killing. It was a revenge killing. It was about two people who are, in a sense, dispossessed. But the person who got killed—not the family so much, but the farmer himself, Clutter—was no ordinary guy. He was no ordinary farmer, but a well-to-do guy with 3,000 acres and some cattle and maybe an oil-pumping system. He was important. He’d worked in government and he’d worked as a county agent. I won’t go into the history of the county agents and their ultimate role in making agribusiness as we know it today. But he was important enough in 1954 to have been interviewed about a kind of global crisis in agriculture in the magazine section of the New York Times.

This wasn’t the story Truman Capote told. Capote was given an assignment by the New Yorker and he went and he did it. He didn’t know or understand any of this background. He didn’t talk about the role of this guy. Not that this guy was the ultimate villain—this Clutter person—but, the fact is, he had a very key role. If he was important enough to be interviewed in a section on changes in agricultural policy in the New York Times Magazine, that means he’s not just nobody. The fact that he conjoined the outlaws, the killers—the fact that they conjoin, in a sense, with the Clutters—I think is a piece of, you can almost say, Dickensian chance. It’s like how some novelists will start out with two or three random incidents that are not connected at all and then mold them together.

I don’t know if you’ve read The Bridge of San Luis Rey? It’s about six or seven people who are on a bridge that collapses; it falls and they’re killed. What it is is an exercise in what brought these people together: what did they have, or not have, in common? Why this moment and not another moment? That’s what I wanted to develop with this, to go a little into the background of how I came to this line of thinking.

Now, one of the killers: his mother was an Indian [sic] and his father was a cowboy. The other one’s parents were poor farmers. So, here, we have three social groups expressed in these people. In the long struggle between corporate agriculture and the individual farmer, this is what develops: they get pushed off the land, these social groups. In fact, this also connects back to the old story of Joseph, in Egypt. With Joseph in Egypt, yes, he predicts the coming famine—the good times and the coming famine. But, when the famine does come, first he takes the farmer’s money, then he takes their land, and he moves them all into the cities. What you’ve got there is kind of an algorithm for the way agriculture develops: we’re talking Russia, the Soviet Union, China. We're talking the United States. It looks different in different places, but the structure remains the same. You urbanize the people and you consolidate the land.

Then, of course, with the book I go into my own reactions to all kinds of literature, and I stop to try to rewrite that literature. For instance, suppose we think of The Iliad as one big trade war. Troy, as you know, sat on the route into the Black Sea, which means it commanded the whole hinterland where people like the Greeks and the Trojans did trading. The Trojan War was a trade war.

BLDGBLOG: The mergers and acquisitions of the ancient world.

Yurick: So that's the kind of stuff I’m working on.

In the end, of course, the smaller farmer fought agribusiness tooth and nail, and they lost. We see what agribusiness has done to food itself, creating all kinds of mutational changes in seeds and so forth. Again, I think of the collectivization period in the Soviet Union in which, in order to win, you had to starve the peasants. That’s what the intellectuals of the time wanted, without understanding the practicality of life on the ground, so to speak. It was a catastrophe.

On the other hand, one of the images I had when I was a kid, during the Depression, was: you’d go see a newsreel and you’d see farmers spilling milk and grain on the ground because they couldn’t get their price. People didn’t have enough food, but they were just dumping their milk in the mud. These were smaller farmers—agribusiness hadn’t happened yet. So you’ve got two greed systems going on here.

Anyway, I use all that as the novel’s jumping-off point. In a sense, I’m saying Clutter had it coming to him—or his class had it coming to him.

But I’m in the very early stages. It becomes like a little race between living and doing it, and ultimately dying. I’m not rushing myself, but I’m having fun.

* * *

This interview was recorded in March 2009. Thank you to Sol Yurick for the conversation. You can also read this interview over on Gizmodo.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This oft-quoted nugget from Arthur C. Clarke is perfectly embodied in this otherworldly model by Nick V. (Brickthing). It’s not often that I’m blown away by the aesthetics of a spacecraft, but Nick is one of the best builders in the community, and has been tearing it up of late. This model, an alien “deity” worshipped by ancient humanity, à la Stargate, is a study in excellence.

To avoid making every other post here on Brothers Brick one of Nick’s new models, I’m also going to point out this stunning bonsai tree.

things people could tip for:

Gerard Rubio’s open-source knitting machine, OpenKnit, can make you a custom sweater in just an hour. I’ve waited in line for a fitting room for longer than that! via hackaday.

For all the hubbub about 3D printers leading a way into a new era of manufacturing, a third industrial revolution, and the beginnings of Star Trek replicators, we really haven’t seen many open source advances in the production of textiles and clothing. You know, the stuff that started the industrial revolution. [Gerard Rubio] is bucking that trend with OpenKnit, an open-source knitting machine that’s able to knit anything from a hat to a sweater using open source hardware and software.

We’ve seen a few builds involving knitting machines, but with few exceptions they’re modifications of extremely vintage Brother machines hacked for automation. OpenKnit is built from the ground up from aluminum extrusion, 3D printed parts, a single servo and stepper motor, and a ton of knitting needles.

The software is based on Knitic, an Arduino-based brain for the old Brother machines. This, combined with an automatic shuttle, allows OpenKnit to knit the sweater seen in the pic above in about an hour.

*I’d suggest checking out that Core77 post, because this video looks like design-fiction, and it isn’t.

“As its name suggests, MX3D-Metal can print lines of steel, stainless steel, aluminum, bronze or copper ‘in mid-air.’

JakkynThis is a brilliant idea!

Creative inspiration as products are exposed in all their glory

We all know the story… the kids who spend hours pulling apart every product they can get their hands on will grow up to become tomorrow’s designers, engineers and creative geniuses. Well, the offices of Bolt in downtown Boston show that this is more than just a cliché.

Building a great hardware product is brutally hard work and our walls remind us of that everyday.

Set with a relatively small budget for decorating the office space in an inspirational way, the Bolt team made a list of their favourite hardware products of all time and purchased each item from eBay. The products were then disassembled, cleaned, and mounted on the walls in all their exploded designer glory.

This can be seen as merely an ‘art project’, with all the innards of the products exposed and neatly knolled into place. But as the exposed products become more and more a part of the every day, they have become valuable tools to educate, inspire and remind of how important exquisite design and meticulous engineering are to the success of a business.

Our ‘art’ was initially intended to decorate the walls, but the longer it’s been up the more often we actually USE it. Companies find it helpful to reference specific parts during design reviews. Molded parts showcase the difference between different plastic textures…

Products on show include design classics from Apple, Dyson, Sony, Braun, Microsoft and Polaroid to name just a few.

(Apple iMac ‘lamp’ version, 2002)

(shown from left: Dyson Air Multiplier, Apple Macbook Pro, OLPC XO-1, Apple iPad 1, Sony Flip Clock, 3COM Palm V)

Click through to the Bolt blog where they discuss some of the thinking behind this design exploration, and the impact that it has had on the creative work environment. You’ll also get to see some more pictures of the exploded products.

It’s great to be reminded that there is design inspiration all around us; all you need to do is take the time to look a little closer. For another example of the inspiration and beauty in manufactured objects, check out this publication by Todd McLellan.

Exploded Hardware via Hack A Day

Posted in Functional Art + Objects, Guy Blashki, Technology by Guy Blashki | Comments are off for this post

*One and a half million Youtube hits in a week? I’d say that strikes a nerve, then.

Published on Dec 17, 2013

“The Cubli is a 15 × 15 × 15 cm cube that can jump up and balance on its corner. Reaction wheels mounted on three faces of the cube rotate at high angular velocities and then brake suddenly, causing the Cubli to jump up. Once the Cubli has almost reached the corner stand up position, controlled motor torques are applied to make it balance on its corner. In addition to balancing, the motor torques can also be used to achieve a controlled fall such that the Cubli can be commanded to fall in any arbitrary direction. Combining these three abilities — jumping up, balancing, and controlled falling — the Cubli is able to ‘walk’.

“Lead Researchers: Gajamohan Mohanarajah and Raffaello D’Andrea

“This work was done at the Institute for Dynamic Systems and Control, ETH Zurich, Switzerland and was funded in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), grant number 146717.”

For more details visit: http://www.idsc.ethz.ch/Research_DAnd…

Other links:

http://robohub.org/swiss-robots-cubli…

Popes! They’re always surprising you. I bet this pope loves to party.

On Tuesday, we reached the first goal in our Patreon drive! Thank you to all of you who chipped in and helped make this such a success. I’m going to do my best to make your patronage worthwhile and enjoyable. I get to keep drawing comics and it’s all thanks to you.

We’ll start sending out your rewards when the first pledges get processed at the end of the month.

The Patreon page will remain up and open to new patrons. If you’re ready to take the dive and pledge a dollar or so per month, we’ll be there waiting for you.

Dead Media Beat: XL Repubblica

I just received news from the ex-editor that XL Repubblica, one of my favorite magazines, has ceased publication. A very Dead Media story — but for me, a heartfelt one.

This mag was created by some with-it Milanese mediated guys who got the ear of a major Italian publishing house. They wrote to me, and asked me to become a founding columnist for their daring, out-of-nowhere effort.

I was properly touched by this mark of the esteem in which I was held in glamorous Milano, so I agreed to give it a try. So I promptly became an Italian mag staffer, writing about future trends, for Italian men. XL Repubblica was an Italian hipster guy mag. Lots of music, shoes, clubs, cars, clothes, travel, some scandal sometimes, some thoughtful pondering of the mystery that is Italian womanhood, and also me, an American cyberpunk futurist.

Although the guys running it were supremely with-it, that plan to publish a category print magazine was old-fashioned, even eight years ago. Mags are still around, but their business is disrupted. You just can’t get the necessary car, clothes and cologne ads together to support the enterprise. That’s not how consumerism works any more. A lot of the economies of scale around printing, shipping, storing and mailing paper are blown to hell, too.

But I cheerfully did it anyway, deck chair on the analog Titanic, because it was the right thing to do. And boy, did I ever write some weird stuff for XL Repubblica. Every month. I never missed a deadline — and here at the end, I feel I can brag about that.

And Jesus, what off-the-wall topics they allowed me. Sometimes, they’d commission something from me — usually about some significant current event — but most of the time they were just, well, “Whatever, maestro!”

My XL column was quite a lot like this blog. Only it was more thought-through, better arranged, and entirely and utterly for Italians. There was something especially cool and weird about its strange, cross-cultural, artificial Italian-ness. It’s super-strange when a foreigner is deliberately trying to explain things to you, from an idiom and point of view that he imagines that you yourself have, and that he thinks you will understand. That sounds and feels weirder, in some ways, than him just simply being foreign. Sometimes you have to marry a foreigner to get it about how mind-distorting and exhilarating that is. It’s like guitar reverb.

So my junket was great, and I think I could have gone on with that task until I was white-haired, feeble, and the oldest young-guy’s futurist in this whole world But: the cruel economics of the Twenty-Teens finally caught up with them. So, XL Repubblica is no more.

Well, I sure learned a lot, doing that. I don’t regret one moment. My heart goes out to everyone associated with this noble effort. They are good people. I hope they thrive in the new year.

A lot of things die at Christmas. It’s the darkest time of the year — at least, in this hemisphere that the USA shares with Italy, that is.

So it goes — as the late Mr. Vonnegut used to pontificate, before he went.

This blog you’re reading won’t last forever, either. It’s haunted by Dead Media, too.

This blog, you see, is actually the remnant of my WIRED USA column. For quite a while, I wrote a column in the WIRED USA print mag, before I became WIRED’s first blogger ever.

The thing I still find cool about this blog — and the reason I still do it here, practically every day — is that it makes absolutely no economic sense. It looks kinda like mainstream publishing, but it isn’t. This blog is a historical accident, and truly a bohemian niche.

I mean, sure, there are some pop up ads floating around over there (((—->))). I hope somebody makes money from those. I don’t. I doubt that you, my blog reader, ever give them any.

My blog here in the shadowed attic of the Conde Nast empire doesn’t even have a topic. It’s just a clearinghouse for general whatever-the-hellness, aimed at a core audience of nobody-in-particular.

Blogging here, for me, is not even an act of labor. It’s scarcely more trouble to me than getting up in the morning and putting on a shirt, pants and shoes. My clothes also distribute public messages, too. My clothes have come to identify me as a traveller. A globalist, a network type, and believe me, I know that attitude of mine is very much part of the problem, in the destruction of so many things I once loved.

Us real futurists, the ones who aren’t kidding about our engagement with the passage of time, we don’t sell that many shiny new cars. But we sure spend a lot of thoughtful time at the graveside.

And sometimes we mourn. We must grieve. A pity about that cool magazine. They were swell.

Over the years, I wrote an absolute ton of XL Repubblica pieces, and I wrote ‘em in English (they were painstakingly translated into Italians by dedicated staffers). Nobody ever read them in English, though — no one but me.

So I thought, in cherished memory of XL — an enterprise I was in from start to finish — I would run one of my favorite XL columns here.

This piece has a very European sensibility, given that it’s mostly about American gadgets. It dates back to about 2008. And if you’re Italian: you know that term you still use, “Crisis”? You’re not in a crisis. A crisis doesn’t ever last that long. You’re not even in a depression, because those also lift after a while, and it’s been a long while. In Southern Europe, you’re in a condition of organized oppression.

*************************

Technology for Tomorrow’s Hard Times

Business news all over the planet is howling that we’re past the edge of financial collapse, so here are some handy technology tips for living in a depression.

You won’t need to worry much about fancy new consumer technology, because a society in a depression lacks consumers. Basically, you can put your trust in two important technical possessions. First, a cheap, sturdy cellphone. Second, a rugged Leatherman “Pocket Survival Tool.” I’ll explain why in a minute.

You don’t have to be married to a Serb (like I am) to understand that Eastern Europe should be your role model for modern collapse. If you want to know what a financial collapse is really like, study the post-Communist “Transition.” The governments went broke, money was worthless, all the major industries slowed or stopped, the police and army lost their credibility, and everything people thought they knew about reality was turned on its head. That’s what it’s like when it gets serious.

Many people died in the Transition — they found they were unable to survive. However, they never died from any huge, imaginary threats to their well-being, such as terrorists, atom bombs, starving mobs, or freezing or starving to death. That’s all the glamorous stuff of science-fiction disaster movies. Most people who died, died from shame. They died from bewilderment, embarrassment, confusion, regret, and despair. Their primary means of death was alcohol.

These casualties were mostly men. They were responsible men who were committed to the collapsing system and took that sense of much failure too personally. They hated being seen in public with their torn shoes, no car, aimless, hopeless, looking like a bum. They couldn’t invent any useful new role for themselves and regain their lost self-respect. So they drank themselves to death.

Women, by contrast, were much less committed to being some sturdy part of the official Communist apparatus, so, during the crisis, women looked after the sick, had pot-luck suppers, washed the laundry, swapped old possessions and, especially, complained a lot. Women took refuge in bargain-hunting, nurturing, bartering, housework, and lamenting. They were too busy to despair, so their casualties were much lower.

This is why you need your cellphone. You will be using your phone to hunt bargains outside the official economic system, which has failed you and all your friends. A failure that large is not your fault. It does not reflect on you personally. Think of it as something like an earthquake. Your dignity, your suit and tie, your fine car — how much energy should you waste on those?

Use your phone to listen carefully to the complaining. Do not beg anybody for help, but find out what your friends are begging for, find that, and give that to them. Your new economic plan is to make them owe you favors. In an economic collapse, personal favors are worth much more than the currency, which is probably inflating or unobtainable. Don’t worry if your favors are not directly returned. You want a big social reputation for being helpful.

Your aim is not to gather cash or earn a salary, but to make yourself visibly valuable to others. Many of your stricken neighbors will be suddenly obsessed with petty crime, violence, looting, revenge and booze. Don’t go into that kind of racketeering; the risk is too high. If you attempt to deal in narcotics, gold, gems, arms, women or money laundering, you will have too much competition.

The best trade goods in a collapse are small, portable luxury items that have become rare because nobody makes them during emergencies: nice items like medicines, condoms, shaving cream, lingerie and candy. While the neighborhood tough guys are busy killing each other for cartons of cigarettes, you’ll have many new friends.

Use your phone to find these valuable things, and whenever you do, always get extra ones. Do not store them or hoard them: give them away for favors. When you live outside the money economy, complaining is the major currency. Listen to the other guy’s complaints, do something practical, then call him on the cellphone to tell him the good news. He’ll be amazed, but also grateful enough to send you text messages about other such opportunities.

If you are the center of a circle of grateful lamenters, you will not drink yourself to death. You will survive. You will not be happier during a depression — that idea is stupid — but you might find that adversity has refined your character. You’ll discover you have skills that you never suspected.

Now we come to the issue of the Leatherman Pocket Survival Tool. Most people in Eastern Europe never had one of these fine devices, which are made of stainless steel and have 25-year warranties. That’s because the Survival Tool was invented by Tim Leatherman, an American engineer who spent time in Eastern Europe.

One of the symptoms of a society destined for collapse is that nobody properly repairs anything. There is general decay all around, because everyone intuitively senses that the enterprise has no future. There is no public money to do large-scale, new, ambitious public projects. Gloomy individuals feel too helpless and scared to take any private initiative.

Thus the Leatherman survival tool, which was designed by Mr. Leatherman to fix the broken things in Eastern Europe. The Survival Tool can fit in a (large) pocket or purse, and it features a neat fold-out arsenal of sturdy steel pliers, knives, saws, screwdrivers, and files. The Leatherman can attack most domestic problems: clumsily, but conveniently.

With or without your Leatherman, you will be a pretty bad amateur handyman. You lack the real tools and real training. Never mind: the professional handymen, the plumbers, electricians and so forth, were too well-paid to find any work, so they’re probably drinking. Your Survival Tool is a psychological prop. This gadget has so many tools, and it offers so many possibilities that, even though you may be lousy at the work, it will keep you from despairing.

Moaning, complaining, despairing people will be hugely impressed when you pull out a huge shiny Leatherman from your pocket, belt or bag, and actually do something. They’ll be grateful even if you screw up, because, after all, they’re not paying you. They’re just watching you cut your way free from the mayhem by refusing to be part of the problem.

And when nobody’s part of the problem, then the problem becomes history.

The internet of things may be coming to us all faster and harder than we'd like.

Reports coming out of Russia suggest that some Chinese domestic appliances, notably kettles, come kitted out with malware—in the shape of small embedded computers that leech off the mains power to the device. The covert computational passenger hunts for unsecured wifi networks, connects to them, and joins a spam and malware pushing botnet. The theory is that a home computer user might eventually twig if their PC is a zombie, but who looks inside the base of their electric kettle, or the casing of their toaster? We tend to forget that the Raspberry Pi is as powerful as an early 90s UNIX server or a late 90s desktop; it costs £25, is the size of a credit card, and runs off a 5 watt USB power source. And there are cheaper, less competent small computers out there. Building them into kettles is a stroke of genius for a budding crime lord looking to build a covert botnet.

But that's not what I'm here to talk about.

I have an iPad. (You may be an Android or Windows RT proponent. Don't stop reading: this is just as applicable to you, too.) I mostly use it as a reacreational gizmo for reading and watching movies, and a little light gaming. But from time to time it's handy to have a keyboard—I use it for email too. So I bought one of these (warning: don't buy it direct, it costs a lot less than £90 on the high street). It's a lovely piece of kit: charges over micro-USB, magnetically clips to the front of the iPad to cover it when not in use, communicates via bluetooth.

But I suddenly had a worrying thought.

This keyboard contains an embedded device powerful enough to run a bluetooth stack. The additional complexity of adding wifi is minimal, as is the power draw if it's designed right. Here's an SD card, with wifi. It's aimed at camera owners: the idea is it can automatically upload your snapshots to the cloud. Turns out it runs Linux and it's hackable.

Look at that cute Logitech bluetooth keyboard. There's a lot of space in it, behind the slot the iPad sits in. Presumably that chunk of the case is full of battery, and the small embedded computer that handles the bluetooth stack. Even if it isn't hackable in its own right, what's to stop someone from buying a bunch of bluetooth keyboards and installing a hidden computer in them? Done properly it'll run a keylogger and some sniffing tools to gather data about the device it's connected to. It stays silent until it detects an open wifi network. Then it can hook up and hork up a hairball of personal data—anything you typed on it—at a command and control server. Best do it stealthily: between the hours of 1am and 4am, and in any event not less than an hour after the most recent keypress.

I hear tablets are catching on everywhere. Want to dabble in industrial espionage? Get a guy with a clipboard to walk into an executive's office and swap their keyboard for an identical-looking one. When they come back from lunch they'll suffer a moment of annoyance when their iPad or Microsoft Surface turns out to have forgotten it's keyboard. But they'll get it paired up again fast, and forget all about it.

I don't want you to think I'm picking on Logitech, by the way. Exactly the same headache applies to every battery-powered bluetooth keyboard. I'm dozy and slow on the uptake: I should have been all over this years ago.

And it's not just keyboards. It's ebook readers. Flashlights. Not your smartphone, but the removable battery in your smartphone. (Have you noticed it running down just a little bit faster?) Your toaster and your kettle are just the start. Could your electric blanket be spying on you? Koomey's law is going to keep pushing the power consumption of our devices down even after Moore's law grinds to a halt: and once Moore's law ends, the only way forward is to commoditize the product of those ultimate fab lines, and churn out chips for pennies. In another decade, we'll have embedded computers running some flavour of Linux where today we have smart inventory control tags—any item in a shop that costs more than about £50, basically. Some of those inventory control tags will be watching and listening to us; and some of their siblings will, repurposed, be piggy-backing a ride home and casing the joint.

The possibilities are endless: it's the dark side of the internet of things. If you'll excuse me now, I've got to go wallpaper my apartment in tinfoil ...

*Gosh, what a swell lecture that is. It’s as crammed with good stuff as a walnut. Anyone with an interest in design fiction should read this, and anyone with a serious interest should read it three times and take notes.

http://blog.tobiasrevell.com/2013/12/critical-design-design-fiction-lecture.html

Every so often a news item grabs my eyeballs and reminds me that I'm supposed to be an amateur futurologist, because of course SF is all about predicting the future (just like astronomy is all about building really big telescopes, and computer science is all about building really fast computers, and, and [insert ironic metaphor here]).

Via MetaFilter, I stumble across the latest development in 3D printing (now that 3D printed handguns have gone mainstream). Mad props go to another printing startup, although that's not what they're marketing themselves as: Fabrican ...

Fabrican is a unlikely-sounding spin-off of the Department of Chemical Engineering, at Imperial College (which in case you're not familiar with it is one of the top engineering/science colleges in the UK; formerly part of the University of London)—at least, it's unlikely until you begin thinking in terms of emulsions, colloids, and the physical chemistry of nanoscale objects. It's basically fabric in a spray can. Tiny fibres suspended in liquid are ejected through a fine nozzle and, as the supernatant evaporates, they adhere to one another. If at this point you're thinking The Jetsons and spray-on clothing, have a cigar: you've fallen for the obvious marketing angle, because if you're trying to market a new product and raise brand awareness among the public, what works better than photographs of serious-faced scientists with paint guns spray-painting hot-looking models with skin-tight instant leotards? (Note: the technical term for this sort of marketing gambit is, or really ought to be, bukake couture.)

The real marketing value pitch is less ambitious, and buried further down the page. Fabrican currently amounts to spray-on felt; a loose mat of unwoven fibres that adhere to one another and naturally entangle. This is brilliant if you're an auto manufacturer, who wants to do away with the laborious hand-fitting of carpets in your cars (just have the paint shop spray the carpet on the floor panels), or a furniture manufacturer who wants to soften the image of those cheap plastic chairs you sell for lecture theatres or buses and commuter rail.

But the implications go much further, because this is just step one. What we're looking at is the first sign of the shift to 3D printing of clothing (and no, Victoria's Secret doesn't count, other than for novelty value, any more than the Honeywell 316/Nieman Marcus Kitchen Computer of 1969 was a sign of the personal computer revolution to come).

Here's the thing: we live in an age of plenty when it comes to clothing—but it relies on a dirty little secret. Clothing has gotten much, much cheaper over the past century; if you ignore the brand premium on Levi's jeans (which have risen in price in real terms, due to going from cheap workware for manual labourers to premium brand name fashion item), a pair of workman's trousers today cost less than a quarter of the equivalent price in 1900. But this fall in prices is local to us, in the developed world. Fabric is woven on mechanical looms, as it has been for a couple of centuries, and garments are still largely cut and entirely sewn by human hands—the greatest enabler of increased productivity was the sewing machine in the 1850s (and, later, the overlocker/serger and other specialised industrial sewing devices). Our cheap clothes are made in sweatshops by underpaid developing world workers, and as Bangladeshi wages rise, the factories migrate to cheaper nations.

A side-effect of separating garment manufacture from consumers (us) is that they don't fit well, either. There are legends of Chinese clothing factories whose first batch of sized-for-western-girth produce has to be rejected by the buyers because nobody on the shop floor believed that the people they were making clothes for could be so fat. Nor do we, in general, have our cheap clothes adjusted to fit. While it's worthwhile to have an expensive suit or formal gown tailored, who would bother fitting a $10 tee-shirt or a $20 pair of jeans? Yes, we have easy access to cheap clothes at prices that make them all but disposable. But we also have cheap clothes that don't fit particularly well and fall apart rapidly.

So, where does spray-on fabric come into this?

We are used to wearing clothes made out of woven (or knitted, or crocheted) fabric—lengths of spun yarn that are interlaced in two dimensions to form a flexible mesh. The individual fibres in cotton or wool or linen or silk may be quite short, but when spun they adhere to each other and this allows us to create thread or yarn many orders of magnitude longer than a fibre.

Right now Fabrican's spray-on felt relies on very short fibres in a liquid carrier that form a matted felt when the solvent dries. (I infer that the strands are probably quite weak, individually, requiring the matting to provide some additional tensile strength.) But I'd like you to imagine the same technology refined so that instead of coming out of a spray-can it comes out of an ink jet printer nozzle. And I'd like you to imagine the same print head also having a different "ink" to print with—a waxy masking substance that can dissolve in an oily dry cleaning fluid and be washed out of the finished garment. Print alternate layers of fabric and mask and the layers of fabric won't adhere to one another. Dry clean after printing and you have separate layers. Give it ink jet printer resolution and you should be able to "print" woven fabric, complete with the warp and weft in situ (separated by the mask layer). The rest of this picture is about ten billion dollars and ten years' worth of fine tuning, and then luxury fibres (synthetic spider silk, anyone?): but the basic premise is that we are between 5 and 20 years away from being able to 3D print woven fabric.

What are the implications?

If you don't think printing woven fabric is a big deal, DARPA beg to differ; DARPA is pumping serious money into robot sewing machines. But automating garment assembly from traditional fabric components turns out to be a really hard problem (as this possibly-paywalled New Scientist article on a €23M project to build a sewbot explains). Cloth is slippery, changes shape if you drop it, wrinkles, and has to be stretched and twisted and folded as it is sewn. Note that final word: sewn. If you can print fabric in situ out of fibres in a liquid form, you don't need to sew components to shape—especially if you can print more than one type and colour of fibre at a time: you can fabricate your "stitches" (inter-layer connections) as part of the process, with minimal hand-finishing to possibly add fasteners (zips or buttons).

Add in a left-field extra: the rapid spread of millimeter wave scanners for airport security. These devices caused a bit of a to-do, earning them the nick-name "perv scanner" in some circles, because of their ability to see through clothing to the skin beneath, in order to check passengers for hidden contraband. But if you put the same machine in a clothes shop, it allows the establishment to obtain extremely accurate measurements of its customers without requiring a strip-tease and manual measurement of all the relevant saggy, lumpy bits and pieces. By use of surface-penetrating wavelengths (possibly high-intensity laser light, or infrared) it may also be possible to automatically distinguish between fatty tissue, musculature, and underlying bone structure. All of which are relevant to the construction of clothing.

So here's my picture of the chain store of the future. You go in, go to the scanning booth, and do the airport-equivalent thing in a variety of positions—stretch and bend as well as hands-up. You then look at the styles on display on the shop floor, pick out what you like, and see it as it will appear on your own body on an avatar on a computer screen. You buy it, and a machine in the back of the store (or an out-of-town lights out 24x7 robotic garment factory) begins to print it. Some time later—maybe minutes, maybe hours or a day or two—the outfit you ordered comes to you. And it fits perfectly, every time. Some items are probably still off-the-shelf (socks, hosiery, maybe even those cheap tee shirts), but anything major is printed, unless you can afford to go to the really high end and pay a human being to make it for you out of natural fibres. Oh, and the printed stuff doesn't have seams in places that chafe or bind.

Now, here's the down-side.

The fabrics on offer to start with will be fugly. Maybe not as bad as the bri-nylon shirts and terylene and other crappy synthetics of yesteryear, but it's still going to be fairly obvious (at first) what you're wearing. Figuring out how to make a sprayable matrix that uses cotton or silk or wool fibres has a multi-billion dollar pay-off at the end, so I expect it to happen eventually, but at first the stuff is going to look and feel like felted nylon. The styles on offer at first will also be fugly. I've spent a few years watching my spouse make her own clothing, and it's worth noting that dress patterns are complex and don't scale linearly: going from a size 12 to a size 18 isn't just a matter of blowing every dimension up by 50%. Clothes that are some variation of a simple tube or tubes will be easier than, say, a pair of jeans (with pockets and decorative seams) let alone an underwired bra or a sports jacket. Nor are there going to be many chain stores left to buy this stuff from. The job of a high street store in this scenario is to take measurements with a scanner and handle order fulfilment. Maybe also to act as a showroom. Today they have changing rooms and act as edge-of-network distribution centres. Tomorrow? Expect tumbleweed where the likes of Macy's or Primark have their bigger stores. Let alone T[J|K] Maxx—that business model is on the way out.

But back to the product itself. The first printed garmets aren't going to eat into the high end fashion market. Rather, they're going to displace sweatshop low-end produce. No, scratch that: initially this stuff is going to be something you spray on conference seats and car body panels (and maybe horrible 70s style flock wallpaper). But sooner or later it'll get good enough for really cheap, semi-disposable clothing. And then the pressure to improve the processes and recapture some of that $100Bn imported-from-China garment market will be irresistible.

So I expect 3D printed clothing will take time to catch on. But as it catches on, a lot of developing world factory workers are going to find their jobs are as obsolete as the half million men who used to work down British coal mines, or the million who worked in iron and steel foundries, or the other countless millions who used to pick crops and plough fields by hand and by horse. People who use sewing machines for a living will find their jobs have gone the same place as people who used to work in office typing pools with carbon paper and manual typewriters. Low status jobs, mostly women, with negligible social safety nets to catch them when they fall. On the other hand, this will hopefully be as much a thing of the past as this.

When garment manufacturing returns to the countries where they're consumed, the pace at which fashion trends turn over may actually accelerate: currently, there's a limit on how fast high street fashion can change imposed by the time it takes to send pattern blocks to a factory overseas, verify that the product is of satisfactory quality, then ship the loaded TEUs to market. It'll be like going from batch processing of punched cards on a mainframe in a computer bureau to using a time-sharing terminal: expect flash fashion trends to take off like a rocket once the tech gets cheap enough and good enough to fit the budget and taste of the vital high street 14-24 year old female demographic (and once the design software gets accessible enough).

It'll take a while longer (if ever—there are strength/durability/flexibility issues here) for 3D printing to revolutionize footwear (but, oh my aching feet, I can't wait).

The hand-sewn couture market (which still exists) will be joined by the not-as-high-end machine-sewn-by-real-people somewhat-more-durable market in the middle end. But it won't be a mass employer.

Now. What am I missing?

Executed in collaboration with KMel robotics, and directed by Sam Brown, Swarm’ takes advanced quadrotor technology out of the testing laboratory and into the real world, to produce a dramatic and engaging story. These unique quadrotors were inspired by the design and material principles of Lexus and constructed to an incredible level of detail and precision. Advanced motion capture camera technology is then used to programme the complex movement paths of each quadrotor, resulting in the stunning movement patterns seen in the film.

It’s a car commercial, but worth watching.

Sweet little pets are transformed in a fire. Crawling from the ashes come forth grinning metallic devils with sharp claws and fire blazing in their eyes.

Blush is a very important organ of the house. Regulates the temperature and keeps it warm and alive. Blue when cold, but blushes with red when warm.

See more at thorunnarnadottir.prosite.com

*Quite an interesting essay on photography and computation. It makes some good points and I agree with many of them, but I also wonder what happens to “photography.” Whenever I pull a dedicated, single-purpose camera out of my pocket and use it these days, I’m aware of performing an archaic act. It’s like stuffing a big briar pipe when everyone around you is electronically vaping tobacco essences.

http://claytoncubitt.com/blog/2013/5/13/on-the-constant-moment

(…)

“Before these tools became widespread, photographers were indeed very much like painters, in both form and function. The camera itself evolved from the camera obscura, literally a “darkened room,” in which one or two people would stand, and record the scene before them, tracing it on wallpaper. Later film-based large format cameras required easel-like tripods and stationary perspectives. Insensitive emulsions required exposure times of many minutes. There was very little difference between a photographer in the field and a painter sketching in the field. As materials improved, and costs reduced, photographers quickly usurped painterly subjects and methods, from formal portraiture to landscapes to still-life, and, having thus freed the painters from the burden of commercial utility, cleared the path for the flowering of the 20th-century modern art movements, from Cubism to Abstract Expressionism to Performance Art.

“So the Decisive Moment itself was merely a form of performance art that the limits of technology forced photographers to engage in. One photographer. One lens. One camera. One angle. One moment. Once you miss it, it is gone forever. Future generations will lament all the decisive moments we lost to these limitations, just as we lament the absence of photographs from pre-photographic eras. But these limitations (the missed moments) were never central to what makes photography an art (the curation of time,) and as the evolution of technology created them, so too is it on the verge of liberating us from them.

“The Decisive Moment is dead. Long live the Constant Moment.

“Imagine an always-recording 360 degree HD wearable networked video camera. (((I find that all too easy to imagine.))) Google Glass is merely an ungainly first step towards this. With a constant feed of all that she might see, the photographer is freed from instant reaction to the Decisive Moment, and then only faced with the Decisive Area to be in, and perhaps the Decisive Angle with which to view it. Already we’ve arrived at the Continuous Moment, but only an early, primitive version.

“Evolve this further into a networked grid of such cameras, and the photographer is freed from these constraints as well, and is then truly a curator of reality after the fact. “Live” input, if any at all, would consist of a “flag” button the photographer presses when she thinks a moment stands out, much like is already used in recording ultra-high-speed footage. DARPA has already developed a camera drone that can stay aloft recording at 1.8 gigapixel resolution for weeks at a time, covering a field as large as 5 miles wide, down to as small as six inches across, and it can archive 70 hours of footage for review. This feat wasn’t achieved with any new expensive sensor breakthroughs, but rather by networking hundreds of cheap off-the-shelf sensors, just like you’ve got in your smartphone.

“With the iPhone 5 camera module currently estimated to cost about $10/unit, and dropping like a rock with the inexorability of Moore’s Law, we can see how even an individual photographer might deploy hundreds of these micro-networked cameras for less than it costs to buy one current professional DSLR….”

*How entirely terrible to be quietly circling some minor-league, well-behaved star, innocently doing a little astronomy… then you realize that something like this is about to happen.

Artist Leonardo Ulian has transformed electronic components into mandalas and sculptures. From a distance, they look like intricate needlepoint, but up-close, resistors, capacitors and diodes appear. Take a look at his framed art, and sculptural trees. Even the tech components can be brought to nature. via colossal.

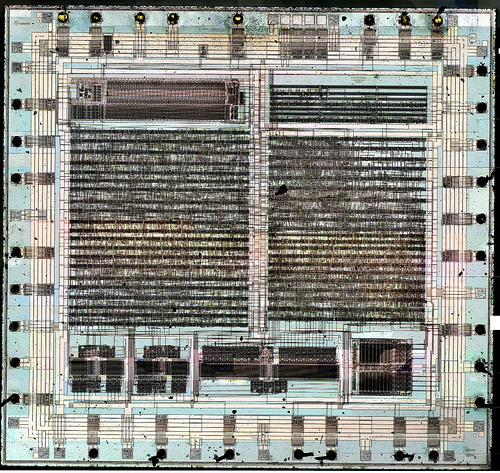

The term "gonzo journalism" gets thrown around pretty loosely, generally referring to stuff that's kind of shouty or over-the-top, but really gonzo stuff is completely, totally bananas. Case in point is James Mickens's The Slow Winter [PDF], a wonderfully lunatic account of the limitations of chip-design that will almost certainly delight you as much as it did me.

The term "gonzo journalism" gets thrown around pretty loosely, generally referring to stuff that's kind of shouty or over-the-top, but really gonzo stuff is completely, totally bananas. Case in point is James Mickens's The Slow Winter [PDF], a wonderfully lunatic account of the limitations of chip-design that will almost certainly delight you as much as it did me.

I think that it used to be fun to be a hardware architect. Anything that you invented would be amazing, and the laws of physics were actively trying to help you succeed. Your friend would say, “I wish that we could predict branches more accurately,” and you’d think, “maybe we can leverage three bits of state per branch to implement a simple saturating counter,” and you’d laugh and declare that such a stupid scheme would never work, but then you’d test it and it would be 94% accurate, and the branches would wake up the next morn- ing and read their newspapers and the headlines would say OUR WORLD HAS BEEN SET ON FIRE. You’d give your buddy a high-five and go celebrate at the bar, and then you’d think, “I wonder if we can make branch predictors even more accurate,” and the next day you’d start XOR’ing the branch’s PC address with a shift register containing the branch’s recent branching history, because in those days, you could XOR anything with anything and get something useful, and you test the new branch predictor, and now you’re up to 96% accuracy, and the branches call you on the phone and say OK, WE GET IT, YOU DO NOT LIKE BRANCHES, but the phone call goes to your voicemail because you’re too busy driving the speed boats and wearing the monocles that you purchased after your promotion at work. You go to work hung-over, and you realize that, during a drunken conference call, you told your boss that your processor has 32 registers when it only has 8, but then you realize THAT YOU CAN TOTALLY LIE ABOUT THE NUMBER OF PHYSICAL REGISTERS, and you invent a crazy hardware mapping scheme from virtual registers to physical ones, and at this point, you start seducing the spouses of the compiler team, because it’s pretty clear that compilers are a thing of the past, and the next generation of processors will run English-level pseudocode directly. Of course, pride precedes the fall, and at some point, you realize that to implement aggressive out-of-order execution, you need to fit more transistors into the same die size, but then a material science guy pops out of a birthday cake and says YEAH WE CAN DO THAT, and by now, you’re touring with Aerosmith and throwing Matisse paintings from hotel room windows, because when you order two Matisse paintings from room service and you get three, that equation is going to be balanced. It all goes so well, and the party keeps getting better. When you retire in 2003, your face is wrinkled from all of the smiles, and even though you’ve been sued by sev- eral pedestrians who suddenly acquired rare paintings as hats, you go out on top, the master of your domain. You look at your son John, who just joined Intel, and you rest well at night, knowing that he can look forward to a pliant universe and an easy life.

The Slow Winter [James Mickens/Usenix]

(via JWZ)

(Image: MYK78 Clipper Chip Lowres, a Creative Commons Attribution (2.0) image from travisgoodspeed's photostream) ![]()

Layer upon layer, each piece tells a fantastic story

The dynamic works of London-based illustrator Martin Tomsky can usually be found bringing children’s books to life… but it’s when he gets his hands on a laser cutter that his imagination really soars.

The layered ply is stained in a number of different shades for added depth, giving the swirling laser cut wood forms a dynamic energy suggestive of a 21st century Hokusai.

Continue after the break to see further examples including details of the 3D effect created by the laser cut wood layers.

This 710mm x 200mm x 25mm piece was commissioned for the Cats and Cartoonists show at Orbital Comics in London.

The following item was inspired by a friend’s father who passed away, a man who loved fishing and was fond of mounting his prize catches.

Like the monsters from mythical stories or the magical worlds of fairy-tales, creatures emerge from the darkest reaches of the forest. The depth of this piece is 40mm.

Click through to the source to see more of these stunning laser cut wooden artworks.

Martin Tomsky via The Dancing Rest

Posted in Functional Art + Objects, Guy Blashki, Laser Cut Wood, Laser Cutting by Guy Blashki | Comments are off for this post

RoboSimian is an ape-like robot designed to meet the disaster-recovery tasks of the DARPA Robotics Challenge.