Shared posts

PICO-8, o incrível console retrô que só existe na internet

Há quem defenda que boa parte da criatividade presente nos jogos de antigamente se deva as limitações que os desenvolvedores enfrentavam e foi pensando nisso (e na ideia de criarmos nosso próprios games), que Joseph “Zep” White resolveu criar o PICO-8, um “fantasy console” que parece os computadores e videogames da década de 80 e que tem atraído vários desenvolvedores indies.

Basicamente o videogame é uma plataforma onde os game designers recebem todas as ferramentas necessárias para poderem desenvolver e compartilhar suas criações, mas tendo que se adequar a uma paleta de 16 cores, uma tela de 128 × 128 pixels, 4 canais para músicas e efeitos sonoros e acredite, “cartuchos” de jogos com no máximo 32 kB.

Por falar nos jogos, eles podem ser distribuídos através de um arquivo PNG especial que também funcionará como sua embalagem e para criá-los é preciso adquirir uma licença no site do projeto, o que custará US$ 15. Já para jogar o que outras pessoas criaram, basta visitar essa lista e aproveitá-los através do próprio navegador. Destaque para os interessantes Dusk Child, Across The River e Tempest.

É claro que os títulos criados para o PICO-8 estão longe de todo o esplendor tecnológico que vemos hoje em dia, mas a proposta está longe de ser esta e o que impressiona é a capacidade de algumas pessoas de criarem coisas tão legais com tão pouco, como por exemplo esse jogo inspirado no Lemmings.

É claro que os títulos criados para o PICO-8 estão longe de todo o esplendor tecnológico que vemos hoje em dia, mas a proposta está longe de ser esta e o que impressiona é a capacidade de algumas pessoas de criarem coisas tão legais com tão pouco, como por exemplo esse jogo inspirado no Lemmings.

Para quem cresceu na década de 80 criando programas e games para máquinas como o ZX Spectrum, brincar com o PICO-8 certamente será uma experiência fantástica, mas para aqueles que não possuem intimidade com a programação ou que estejam apenas interessados em conhecer algumas criações de pessoas que não se intimidam com limitações técnicas, vale muito a pena acompanhar a comunidade que está se formando em torno deste console virtual.

Se quiser conhecer um pouco mais sobre o que levou Zep White a apostar nessa ideia, recomendo dar uma olhada em um fanzine que pode ser baixado gratuitamente aqui ou cuja versão física pode ser adquirida neste site.

The post PICO-8, o incrível console retrô que só existe na internet appeared first on Meio Bit.

Batman da vida real ajuda menino que sofria com bullying!

Nos Estados Unidos existem vários Batmans pelo país, são homens que se vestem como o super-herói para fazer palestras motivacionais para crianças em várias escolas pelos seus municípios.

No domingo Lenny Robinson, conhecido como o Batman da Rota 29, resgatou um menino de oito anos chamada Jacob de um bully.

Após a biga ser resolvida, ele prometeu sempre proteger o pequeno Jacob, mas Robinson morreu tragicamente num acidente de carro no mesmo dia.

Então outro Batman, o de Huntington, foi até a escola de Jacob na segunda-feira afirmando que ia manter sua promessa.

“O que aconteceu este final de semana com Lenny, o Batman de Maryland, e o momento que ele teve com o Jacob. Todo o Exército do Batman e o mundo precisa ter isso como inspiração” afirmou John Auckland, o Batman de Huntington.

Auckland deixou uma mensagem anti-bullying na Dunbar Intermediate School, dizendo: “Você não precisa de superpoderes para ser o Batman, vocês entendem isso? O Batman não tem nenhum. É tudo bugingangas e se preocupar com os outros.”.

Jacob respondeu: “Eu faço parte do Exército do Batman agora!”.

O Batman poderá ser visto nos cinemas em breve em Batman vs Superman: A Origem da Justiça, que estreia em 24 de março de 2016 no Brasil!

Fonte: CB

AEP: Woman makes “hello i am a feminist” her Tinder bio. The results made her an Instagram star.

Loading More

Permanent Link

Embed Code

Hi ,

We need to confirm your email address for this account.

Thanks!

We have sent you an email so you can confirm the address you provided.

Thanks for Signing Up!

We have sent you an email so you can confirm the email address you provided.

Just click this tiny button to like us on Facebook.

If you've already liked us on Facebook just click here and let's pretend this never happened.

Hemagglutinin-stem nanoparticles generate heterosubtypic influenza protection

The Nature article is here. The FT put it differently: “Scientists make breakthrough in search for universal flu vaccine” Here are many other articles on the same.

And how long did it take us, starting more or less from scratch, to make that Ebola vaccine?

Is it possible that our vaccine development capacity is seriously better than say ten years ago?

Are the biggest potential winners China, India, Indonesia, and Nigeria?

For a relevant pointer I thank J.

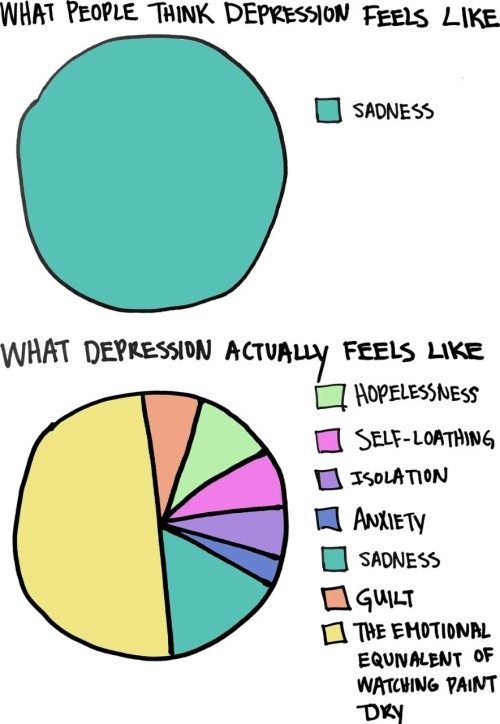

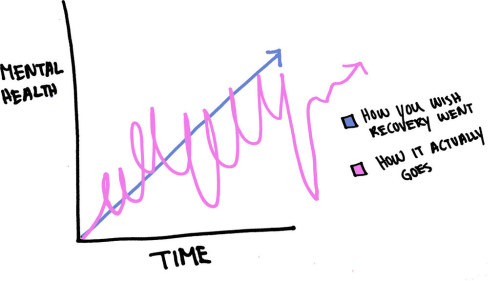

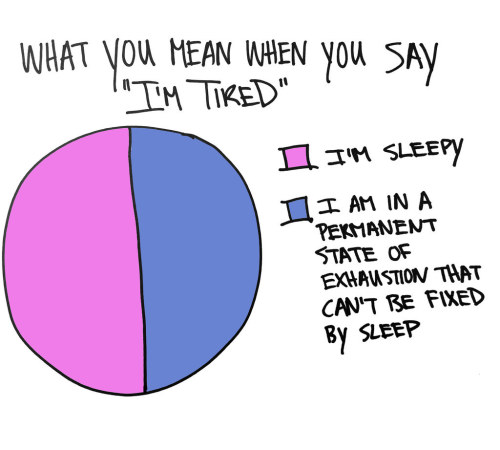

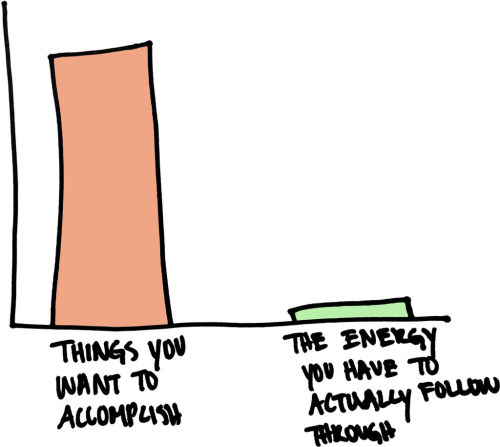

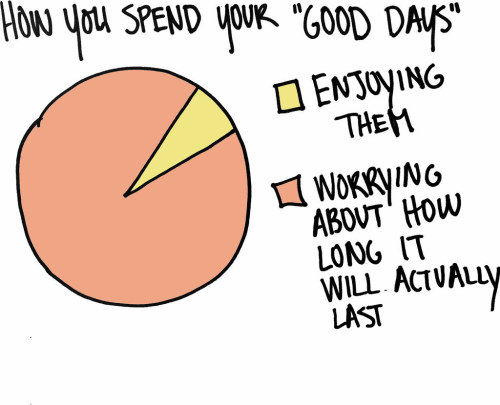

thysweetpoison: Understanding How Depression Feels (via...

Albener Pessoa(via firehose)

Já escolhi a minha funerária

Eu não tenho acompanhado nos últimos 20 anos como anda o mercado do marketing funerário, mas ao que tudo indica essa é uma das melhores propagandas que existem.

Foi filmada EM PÉ por um celular? Foi.

As meninas estão odiando estar ali? Estão.

Mas essa cena delas saindo de dentro do caixão me conquistou de um jeito que não consigo explicar.

vi no Ah Negão

Client: I want to start thinking outside of the box with our presentations.Me: What do you mean...

Client: I want to start thinking outside of the box with our presentations.

Me: What do you mean exactly?

Client: I think we should do our PowerPoints with a portrait layout instead of landscape.

Me: PowerPoints are landscapes so they use up all the space on a computer screen or projector. That’s why it’s the way it is.

Client: But if we did it like a portrait, everyone would think it was edgy and different. You’ve got to think outside of the box.

AEP : Common Knowledge and Aumann’s Agreement Theorem

The following is the prepared version of a talk that I gave at SPARC: a two-week high-school summer program about applied rationality held in Berkeley, CA for the past two weeks. I had a wonderful time in Berkeley, meeting new friends and old, but I’m now leaving to visit the CQT in Singapore, and then to attend the AQIS conference in Seoul.

Common Knowledge and Aumann’s Agreement Theorem

August 14, 2015

Thank you so much for inviting me here! I honestly don’t know whether it’s possible to teach applied rationality, the way this camp is trying to do. What I know is that, if it is possible, then the people running SPARC are some of the awesomest people on earth to figure out how. I’m incredibly proud that Chelsea Voss and Paul Christiano are both former students of mine, and I’m amazed by the program they and the others have put together here. I hope you’re all having fun—or maximizing your utility functions, or whatever.

My research is mostly about quantum computing, and more broadly, computation and physics. But I was asked to talk about something you can actually use in your lives, so I want to tell a different story, involving common knowledge.

I’ll start with the “Muddy Children Puzzle,” which is one of the greatest logic puzzles ever invented. How many of you have seen this one?

OK, so the way it goes is, there are a hundred children playing in the mud. Naturally, they all have muddy foreheads. At some point their teacher comes along and says to them, as they all sit around in a circle: “stand up if you know your forehead is muddy.” No one stands up. For how could they know? Each kid can see all the other 99 kids’ foreheads, so knows that they’re muddy, but can’t see his or her own forehead. (We’ll assume that there are no mirrors or camera phones nearby, and also that this is mud that you don’t feel when it’s on your forehead.)

So the teacher tries again. “Knowing that no one stood up the last time, now stand up if you know your forehead is muddy.” Still no one stands up. Why would they? No matter how many times the teacher repeats the request, still no one stands up.

Then the teacher tries something new. “Look, I hereby announce that at least one of you has a muddy forehead.” After that announcement, the teacher again says, “stand up if you know your forehead is muddy”—and again no one stands up. And again and again; it continues 99 times. But then the hundredth time, all the children suddenly stand up.

(There’s a variant of the puzzle involving blue-eyed islanders who all suddenly commit suicide on the hundredth day, when they all learn that their eyes are blue—but as a blue-eyed person myself, that’s always struck me as needlessly macabre.)

What’s going on here? Somehow, the teacher’s announcing to the children that at least one of them had a muddy forehead set something dramatic in motion, which would eventually make them all stand up—but how could that announcement possibly have made any difference? After all, each child already knew that at least 99 children had muddy foreheads!

Like with many puzzles, the way to get intuition is to change the numbers. So suppose there were two children with muddy foreheads, and the teacher announced to them that at least one had a muddy forehead, and then asked both of them whether their own forehead was muddy. Neither would know. But each child could reason as follows: “if my forehead weren’t muddy, then the other child would’ve seen that, and would also have known that at least one of us has a muddy forehead. Therefore she would’ve known, when asked, that her own forehead was muddy. Since she didn’t know, that means my forehead is muddy.” So then both children know their foreheads are muddy, when the teacher asks a second time.

Now, this argument can be generalized to any (finite) number of children. The crucial concept here is common knowledge. We call a fact “common knowledge” if, not only does everyone know it, but everyone knows everyone knows it, and everyone knows everyone knows everyone knows it, and so on. It’s true that in the beginning, each child knew that all the other children had muddy foreheads, but it wasn’t common knowledge that even one of them had a muddy forehead. For example, if your forehead and mine are both muddy, then I know that at least one of us has a muddy forehead, and you know that too, but you don’t know that I know it (for what if your forehead were clean?), and I don’t know that you know it (for what if my forehead were clean?).

What the teacher’s announcement did, was to make it common knowledge that at least one child has a muddy forehead (since not only did everyone hear the announcement, but everyone witnessed everyone else hearing it, etc.). And once you understand that point, it’s easy to argue by induction: after the teacher asks and no child stands up (and everyone sees that no one stood up), it becomes common knowledge that at least two children have muddy foreheads (since if only one child had had a muddy forehead, that child would’ve known it and stood up). Next it becomes common knowledge that at least three children have muddy foreheads, and so on, until after a hundred rounds it’s common knowledge that everyone’s forehead is muddy, so everyone stands up.

The moral is that the mere act of saying something publicly can change the world—even if everything you said was already obvious to every last one of your listeners. For it’s possible that, until your announcement, not everyone knew that everyone knew the thing, or knew everyone knew everyone knew it, etc., and that could have prevented them from acting.

This idea turns out to have huge real-life consequences, to situations way beyond children with muddy foreheads. I mean, it also applies to children with dots on their foreheads, or “kick me” signs on their backs…

But seriously, let me give you an example I stole from Steven Pinker, from his wonderful book The Stuff of Thought. Two people of indeterminate gender—let’s not make any assumptions here—go on a date. Afterward, one of them says to the other: “Would you like to come up to my apartment to see my etchings?” The other says, “Sure, I’d love to see them.”

This is such a cliché that we might not even notice the deep paradox here. It’s like with life itself: people knew for thousands of years that every bird has the right kind of beak for its environment, but not until Darwin and Wallace could anyone articulate why (and only a few people before them even recognized there was a question there that called for a non-circular answer).

In our case, the puzzle is this: both people on the date know perfectly well that the reason they’re going up to the apartment has nothing to do with etchings. They probably even both know the other knows that. But if that’s the case, then why don’t they just blurt it out: “would you like to come up for some intercourse?” (Or “fluid transfer,” as the John Nash character put it in the Beautiful Mind movie?)

So here’s Pinker’s answer. Yes, both people know why they’re going to the apartment, but they also want to avoid their knowledge becoming common knowledge. They want plausible deniability. There are several possible reasons: to preserve the romantic fantasy of being “swept off one’s feet.” To provide a face-saving way to back out later, should one of them change their mind: since nothing was ever openly said, there’s no agreement to abrogate. In fact, even if only one of the people (say A) might care about such things, if the other person (say B) thinks there’s any chance A cares, B will also have an interest in avoiding common knowledge, for A’s sake.

Put differently, the issue is that, as soon as you say X out loud, the other person doesn’t merely learn X: they learn that you know X, that you know that they know that you know X, that you want them to know you know X, and an infinity of other things that might upset the delicate epistemic balance. Contrast that with the situation where X is left unstated: yeah, both people are pretty sure that “etchings” are just a pretext, and can even plausibly guess that the other person knows they’re pretty sure about it. But once you start getting to 3, 4, 5, levels of indirection—who knows? Maybe you do just want to show me some etchings.

Philosophers like to discuss Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty meeting in a train station, and Moriarty declaring, “I knew you’d be here,” and Holmes replying, “well, I knew that you knew I’d be here,” and Moriarty saying, “I knew you knew I knew I’d be here,” etc. But real humans tend to be unable to reason reliably past three or four levels in the knowledge hierarchy. (Related to that, you might have heard of the game where everyone guesses a number between 0 and 100, and the winner is whoever’s number is the closest to 2/3 of the average of all the numbers. If this game is played by perfectly rational people, who know they’re all perfectly rational, and know they know, etc., then they must all guess 0—exercise for you to see why. Yet experiments show that, if you actually want to win this game against average people, you should guess about 20. People seem to start with 50 or so, iterate the operation of multiplying by 2/3 a few times, and then stop.)

Incidentally, do you know what I would’ve given for someone to have explained this stuff to me back in high school? I think that a large fraction of the infamous social difficulties that nerds have, is simply down to nerds spending so much time in domains (like math and science) where the point is to struggle with every last neuron to make everything common knowledge, to make all truths as clear and explicit as possible. Whereas in social contexts, very often you’re managing a delicate epistemic balance where you need certain things to be known, but not known to be known, and so forth—where you need to prevent common knowledge from arising, at least temporarily. “Normal” people have an intuitive feel for this; it doesn’t need to be explained to them. For nerds, by contrast, explaining it—in terms of the muddy children puzzle and so forth—might be exactly what’s needed. Once they’re told the rules of a game, nerds can try playing it too! They might even turn out to be good at it.

OK, now for a darker example of common knowledge in action. If you read accounts of Nazi Germany, or the USSR, or North Korea or other despotic regimes today, you can easily be overwhelmed by this sense of, “so why didn’t all the sane people just rise up and overthrow the totalitarian monsters? Surely there were more sane people than crazy, evil ones. And probably the sane people even knew, from experience, that many of their neighbors were sane—so why this cowardice?” Once again, it could be argued that common knowledge is the key. Even if everyone knows the emperor is naked; indeed, even if everyone knows everyone knows he’s naked, still, if it’s not common knowledge, then anyone who says the emperor’s naked is knowingly assuming a massive personal risk. That’s why, in the story, it took a child to shift the equilibrium. Likewise, even if you know that 90% of the populace will join your democratic revolt provided they themselves know 90% will join it, if you can’t make your revolt’s popularity common knowledge, everyone will be stuck second-guessing each other, worried that if they revolt they’ll be an easily-crushed minority. And because of that very worry, they’ll be correct!

(My favorite Soviet joke involves a man standing in the Moscow train station, handing out leaflets to everyone who passes by. Eventually, of course, the KGB arrests him—but they discover to their surprise that the leaflets are just blank pieces of paper. “What’s the meaning of this?” they demand. “What is there to write?” replies the man. “It’s so obvious!” Note that this is precisely a situation where the man is trying to make common knowledge something he assumes his “readers” already know.)

The kicker is that, to prevent something from becoming common knowledge, all you need to do is censor the common-knowledge-producing mechanisms: the press, the Internet, public meetings. This nicely explains why despots throughout history have been so obsessed with controlling the press, and also explains how it’s possible for 10% of a population to murder and enslave the other 90% (as has happened again and again in our species’ sorry history), even though the 90% could easily overwhelm the 10% by acting in concert. Finally, it explains why believers in the Enlightenment project tend to be such fanatical absolutists about free speech—why they refuse to “balance” it against cultural sensitivity or social harmony or any other value, as so many well-meaning people urge these days.

OK, but let me try to tell you something surprising about common knowledge. Here at SPARC, you’ve learned all about Bayes’ rule—how, if you like, you can treat “probabilities” as just made-up numbers in your head, which are required obey the probability calculus, and then there’s a very definite rule for how to update those numbers when you gain new information. And indeed, how an agent that wanders around constantly updating these numbers in its head, and taking whichever action maximizes its expected utility (as calculated using the numbers), is probably the leading modern conception of what it means to be “rational.”

Now imagine that you’ve got two agents, call them Alice and Bob, with common knowledge of each other’s honesty and rationality, and with the same prior probability distribution over some set of possible states of the world. But now imagine they go out and live their lives, and have totally different experiences that lead to their learning different things, and having different posterior distributions. But then they meet again, and they realize that their opinions about some topic (say, Hillary’s chances of winning the election) are common knowledge: they both know each other’s opinion, and they both know that they both know, and so on. Then a striking 1976 result called Aumann’s Theorem states that their opinions must be equal. Or, as it’s summarized: “rational agents with common priors can never agree to disagree about anything.”

Actually, before going further, let’s prove Aumann’s Theorem—since it’s one of those things that sounds like a mistake when you first hear it, and then becomes a triviality once you see the 3-line proof. (Albeit, a “triviality” that won Aumann a Nobel in economics.) The key idea is that knowledge induces a partition on the set of possible states of the world. Huh? OK, imagine someone is either an old man, an old woman, a young man, or a young woman. You and I agree in giving each of these a 25% prior probability. Now imagine that you find out whether they’re a man or a woman, and I find out whether they’re young or old. This can be illustrated as follows:

The diagram tells us, for example, that if the ground truth is “old woman,” then your knowledge is described by the set {old woman, young woman}, while my knowledge is described by the set {old woman, old man}. And this different information leads us to different beliefs: for example, if someone asks for the probability that the person is a woman, you’ll say 100% but I’ll say 50%. OK, but what does it mean for information to be common knowledge? It means that I know that you know that I know that you know, and so on. Which means that, if you want to find out what’s common knowledge between us, you need to take the least common coarsening of our knowledge partitions. I.e., if the ground truth is some given world w, then what do I consider it possible that you consider it possible that I consider possible that … etc.? Iterate this growth process until it stops, by “zigzagging” between our knowledge partitions, and you get the set S of worlds such that, if we’re in world w, then what’s common knowledge between us is that the world belongs to S. Repeat for all w’s, and you get the least common coarsening of our partitions. In the above example, the least common coarsening is trivial, with all four worlds ending up in the same set S, but there are nontrivial examples as well:

Now, if Alice’s expectation of a random variable X is common knowledge between her and Bob, that means that everywhere in S, her expectation must be constant … and hence must equal whatever the expectation is, over all the worlds in S! Likewise, if Bob’s expectation is common knowledge with Alice, then everywhere in S, it must equal the expectation of X over S. But that means that Alice’s and Bob’s expectations are the same.

There are lots of related results. For example, rational agents with common priors, and common knowledge of each other’s rationality, should never engage in speculative trade (e.g., buying and selling stocks, assuming that they don’t need cash, they’re not earning a commission, etc.). Why? Basically because, if I try to sell you a stock for (say) $50, then you should reason that the very fact that I’m offering it means I must have information you don’t that it’s worth less than $50, so then you update accordingly and you don’t want it either.

Or here’s another one: suppose again that we’re Bayesians with common priors, and we’re having a conversation, where I tell you my opinion (say, of the probability Hillary will win the election). Not any of the reasons or evidence on which the opinion is based—just the opinion itself. Then you, being Bayesian, update your probabilities to account for what my opinion is. Then you tell me your opinion (which might have changed after learning mine), I update on that, I tell you my new opinion, then you tell me your new opinion, and so on. You might think this could go on forever! But, no, Geanakoplos and Polemarchakis observed that, as long as there are only finitely many possible states of the world in our shared prior, this process must converge after finitely many steps with you and me having the same opinion (and moreover, with it being common knowledge that we have that opinion). Why? Because as long as our opinions differ, your telling me your opinion or me telling you mine must induce a nontrivial refinement of one of our knowledge partitions, like so:

I.e., if you learn something new, then at least one of your knowledge sets must get split along the different possible values of the thing you learned. But since there are only finitely many underlying states, there can only be finitely many such splittings (note that, since Bayesians never forget anything, knowledge sets that are split will never again rejoin).

And something else: suppose your friend tells you a liberal opinion, then you take it into account, but reply with a more conservative opinion. The friend takes your opinion into account, and replies with a revised opinion. Question: is your friend’s new opinion likelier to be more liberal than yours, or more conservative?

Obviously, more liberal! Yes, maybe your friend now sees some of your points and vice versa, maybe you’ve now drawn a bit closer (ideally!), but you’re not going to suddenly switch sides because of one conversation.

Yet, if you and your friend are Bayesians with common priors, one can prove that that’s not what should happen at all. Indeed, your expectation of your own future opinion should equal your current opinion, and your expectation of your friend’s next opinion should also equal your current opinion—meaning that you shouldn’t be able to predict in which direction your opinion will change next, nor in which direction your friend will next disagree with you. Why not? Formally, because all these expectations are just different ways of calculating an expectation over the same set, namely your current knowledge set (i.e., the set of states of the world that you currently consider possible)! More intuitively, we could say: if you could predict that, all else equal, the next thing you heard would probably shift your opinion in a liberal direction, then as a Bayesian you should already shift your opinion in a liberal direction right now. (This is related to what’s called the “martingale property”: sure, a random variable X could evolve in many ways in the future, but the average of all those ways must be its current expectation E[X], by the very definition of E[X]…)

So, putting all these results together, we get a clear picture of what rational disagreements should look like: they should follow unbiased random walks, until sooner or later they terminate in common knowledge of complete agreement. We now face a bit of a puzzle, in that hardly any disagreements in the history of the world have ever looked like that. So what gives?

There are a few ways out:

(1) You could say that the “failed prediction” of Aumann’s Theorem is no surprise, since virtually all human beings are irrational cretins, or liars (or at least, it’s not common knowledge that they aren’t). Except for you, of course: you’re perfectly rational and honest. And if you ever met anyone else as rational and honest as you, maybe you and they could have an Aumannian conversation. But since such a person probably doesn’t exist, you’re totally justified to stand your ground, discount all opinions that differ from yours, etc. Notice that, even if you genuinely believed that was all there was to it, Aumann’s Theorem would still have an aspirational significance for you: you would still have to say this is the ideal that all rationalists should strive toward when they disagree. And that would already conflict with a lot of standard rationalist wisdom. For example, we all know that arguments from authority carry little weight: what should sway you is not the mere fact of some other person stating their opinion, but the actual arguments and evidence that they’re able to bring. Except that as we’ve seen, for Bayesians with common priors this isn’t true at all! Instead, merely hearing your friend’s opinion serves as a powerful summary of everything your friend knows that could possibly be relevant to the question. And if you learn that your rational friend disagrees with you, then even without knowing why, you should take that as seriously as if you discovered a contradiction in your own thought processes. This is related to an even broader point: there’s a normative rule of rationality that you should judge ideas only on their merits—yet if you’re a Bayesian, of course you’re going to take into account where the ideas come from, and how many other people hold them! Likewise, if you’re a Bayesian police officer or a Bayesian airport screener or a Bayesian job interviewer, of course you’re going to profile people by their superficial characteristics, however unfair that might be to individuals—so all those studies proving that people evaluate the same resume differently if you change the name at the top are no great surprise. It seems to me that the tension between these two different views of rationality, the normative and the Bayesian, generates a lot of the most intractable debates of the modern world.

(2) Or—and this is an obvious one—you could reject the assumption of common priors. After all, isn’t a major selling point of Bayesianism supposed to be its subjective aspect, the fact that you pick “whichever prior feels right for you,” and are constrained only in how to update that prior? If Alice’s and Bob’s priors can be different, then all the reasoning I went through earlier collapses. So rejecting common priors might seem appealing. But there’s a paper by Tyler Cowen and Robin Hanson called “Are Disagreements Honest?”—one of the most worldview-destabilizing papers I’ve ever read—that calls that strategy into question. What it says, basically, is this: if you’re really a thoroughgoing Bayesian rationalist, then your prior ought to allow for the possibility that you are the other person. Or to put it another way: “you being born as you,” rather than as someone else, should be treated as just one more contingent fact that you observe and then conditionalize on! And likewise, the other person should condition on the observation that they’re them and not you. In this way, absolutely everything that makes you different from someone else can be understood as “differing information,” so we’re right back to the situation covered by Aumann’s Theorem. Imagine, if you like, that we all started out behind some Rawlsian veil of ignorance, as pure reasoning minds that had yet to be assigned specific bodies. In that original state, there was nothing to differentiate any of us from any other—anything that did would just be information to condition on—so we all should’ve had the same prior. That might sound fanciful, but in some sense all it’s saying is: what licenses you to privilege an observation just because it’s your eyes that made it, or a thought just because it happened to occur in your head? Like, if you’re objectively smarter or more observant than everyone else around you, fine, but to whatever extent you agree that you aren’t, your opinion gets no special epistemic protection just because it’s yours.

(3) If you’re uncomfortable with this tendency of Bayesian reasoning to refuse to be confined anywhere, to want to expand to cosmic or metaphysical scope (“I need to condition on having been born as me and not someone else”)—well then, you could reject the entire framework of Bayesianism, as your notion of rationality. Lest I be cast out from this camp as a heretic, I hasten to say: I include this option only for the sake of completeness!

(4) When I first learned about this stuff 12 years ago, it seemed obvious to me that a lot of it could be dismissed as irrelevant to the real world for reasons of complexity. I.e., sure, it might apply to ideal reasoners with unlimited time and computational power, but as soon as you impose realistic constraints, this whole Aumannian house of cards should collapse. As an example, if Alice and Bob have common priors, then sure they’ll agree about everything if they effectively share all their information with each other! But in practice, we don’t have time to “mind-meld,” swapping our entire life experiences with anyone we meet. So one could conjecture that agreement, in general, requires a lot of communication. So then I sat down and tried to prove that as a theorem. And you know what I found? That my intuition here wasn’t even close to correct!

In more detail, I proved the following theorem. Suppose Alice and Bob are Bayesians with shared priors, and suppose they’re arguing about (say) the probability of some future event—or more generally, about any random variable X bounded in [0,1]. So, they have a conversation where Alice first announces her expectation of X, then Bob announces his new expectation, and so on. The theorem says that Alice’s and Bob’s estimates of X will necessarily agree to within ±ε, with probability at least 1-δ over their shared prior, after they’ve exchanged only O(1/(δε2)) messages. Note that this bound is completely independent of how much knowledge they have; it depends only on the accuracy with which they want to agree! Furthermore, the same bound holds even if Alice and Bob only send a few discrete bits about their real-valued expectations with each message, rather than the expectations themselves.

The proof involves the idea that Alice and Bob’s estimates of X, call them XA and XB respectively, follow “unbiased random walks” (or more formally, are martingales). Very roughly, if |XA-XB|≥ε with high probability over Alice and Bob’s shared prior, then that fact implies that the next message has a high probability (again, over the shared prior) of causing either XA or XB to jump up or down by about ε. But XA and XB, being estimates of X, are bounded between 0 and 1. So a random walk with a step size of e can only continue for about 1/ε2 steps before it hits one of the “absorbing barriers.”

The way to formalize this is to look at the variances, Var[XA] and Var[XB], with respect to the shared prior. Because Alice and Bob’s partitions keep getting refined, the variances are monotonically non-decreasing. They start out 0 and can never exceed 1 (in fact they can never exceed 1/4, but let’s not worry about constants). Now, the key lemma is that, if Pr[|XA-XB|≥ε]≥δ, then Var[XB] must increase by at least δε2 if Alice sends XA to Bob, and Var[XA] must increase by at least δε2 if Bob sends XB to Alice. You can see my paper for the proof, or just work it out for yourself. At any rate, the lemma implies that, after O(1/(δε2)) rounds of communication, there must be at least a temporary break in the disagreement; there must be some round where Alice and Bob approximately agree with high probability.

There are lots of other results in my paper, including an upper bound on the number of calls that Alice and Bob need to make to a “sampling oracle” to carry out this sort of protocol approximately, assuming they’re not perfect Bayesians but agents with bounded computational power. But let me step back and address the broader question: what should we make of all this? How should we live with the gargantuan chasm between the prediction of Bayesian rationality for how we should disagree, and the actual facts of how we do disagree?

We could simply declare that human beings are not well-modeled as Bayesians with common priors—that we’ve failed in giving a descriptive account of human behavior—and leave it at that. OK, but that would still leave the question: does this stuff have normative value? Should it affect how we behave, if we want to consider ourselves honest and rational? I would argue, possibly yes.

Yes, you should constantly ask yourself the question: “would I still be defending this opinion, if I had been born as someone else?” (Though you might say this insight predates Aumann by quite a bit, going back at least to Spinoza.)

Yes, if someone you respect as honest and rational disagrees with you, you should take it as seriously as if the disagreement were between two different aspects of yourself.

Finally, yes, we can try to judge epistemic communities by how closely they approach the Aumannian ideal. In math and science, in my experience, it’s common to see two people furiously arguing with each other at a blackboard. Come back five minutes later, and they’re arguing even more furiously, but now their positions have switched. As we’ve seen, that’s precisely what the math says a rational conversation should look like. In social and political discussions, though, usually the very best you’ll see is that two people start out diametrically opposed, but eventually one of them says “fine, I’ll grant you this,” and the other says “fine, I’ll grant you that.” We might say, that’s certainly better than the common alternative, of the two people walking away even more polarized than before! Yet the math tells us that even the first case—even the two people gradually getting closer in their views—is nothing at all like a rational exchange, which would involve the two participants repeatedly leapfrogging each other, completely changing their opinion about the question under discussion (and then changing back, and back again) every time they learned something new. The first case, you might say, is more like haggling—more like “I’ll grant you that X is true if you grant me that Y is true”—than like our ideal friendly mathematicians arguing at the blackboard, whose acceptance of new truths is never slow or grudging, never conditional on the other person first agreeing with them about something else.

Armed with this understanding, we could try to rank fields by how hard it is to have an Aumannian conversation in them. At the bottom—the easiest!—is math (or, let’s say, chess, or debugging a program, or fact-heavy fields like lexicography or geography). Crucially, here I only mean the parts of these subjects with agreed-on rules and definite answers: once the conversation turns to whose theorems are deeper, or whose fault the bug was, things can get arbitrarily non-Aumannian. Then there’s the type of science that involves messy correlational studies (I just mean, talking about what’s a risk factor for what, not the political implications). Then there’s politics and aesthetics, with the most radioactive topics like Israel/Palestine higher up. And then, at the very peak, there’s gender and social justice debates, where everyone brings their formative experiences along, and absolutely no one is a disinterested truth-seeker, and possibly no Aumannian conversation has ever been had in the history of the world.

I would urge that even at the very top, it’s still incumbent on all of us to try to make the Aumannian move, of “what would I think about this issue if I were someone else and not me? If I were a man, a woman, black, white, gay, straight, a nerd, a jock? How much of my thinking about this represents pure Spinozist reason, which could be ported to any rational mind, and how much of it would get lost in translation?”

Anyway, I’m sure some people would argue that, in the end, the whole framework of Bayesian agents, common priors, common knowledge, etc. can be chucked from this discussion like so much scaffolding, and the moral lessons I want to draw boil down to trite advice (“try to see the other person’s point of view”) that you all knew already. Then again, even if you all knew all this, maybe you didn’t know that you all knew it! So I hope you gained some new information from this talk in any case. Thanks.

Update: Coincidentally, there’s a moving NYT piece by Oliver Sacks, which (among other things) recounts his experiences with his cousin, the Aumann of Aumann’s theorem.

Another Update: If I ever did attempt an Aumannian conversation with someone, the other Scott A. would be a candidate! Here he is in 2011 making several of the same points I did above, using the same examples (I thank him for pointing me to his post).

AEP : J.K. Rowling Has Endorsed A Script-Flipping Theory About Dumbledore

By now, if you're a Harry Potter fan and frequent the internet you've probably seen the theory floating around about Albus Dumbledore's role in the Deathly Hallows theory.

Source: your-bvcky.tumblr.com

The post explaining the theory has been making the rounds online for a while now, baffling readers with its simplicity (and air-tight application).

(Here's the "Tale of the Three Brothers" if you need a refresher.)

According to the theory on Tumblr, Voldemort represents the eldest, power-hungry brother; Snape is the grieving middle brother; and Harry is the youngest. And Dumbledore? He's death itself.

Like every good theory, it changes the way you see everything.

Just think about it: Snape, Voldemort, and Harry each fit the Peverell brothers so well, not just because of what happens to them, but because of their motivations. Oh, and Voldemort only feared one wizard, Dumbledore. And HE ONLY FEARED DEATH.

But, as with all Potter fan theories that circulate the net, there's only one person who can truly endorse their accuracy, and that's Ms. Rowling herself.

And there you have it: The ultimate seal of approval.

Doesn't get any better than that, folks.

AEP : Here's Why You Should Think Twice Before Buying That Fancy New Camera

All right fine, I'm not really at war with gear. It is, after all, an essential part of the filmmaking process. Without a camera, microphone, and a way to edit it all together, there would be no conceivable way to make live action films. Simple as that.

However, in the past few years, our relationship with gear has become counterproductive, and that's putting it mildly. In essence, we find ourselves in a weird psychologically-crippling loop in which the gear we have is not good enough to produce anything meaningful, and the gear we're about to have will make us whole and put our creative woes to rest. But it never does. And the cycle continues.

So, with that in mind, here's Simon Cade to explain why he's been using a Canon T3i for the past few years, and why he absolutely won't be upgrading to a new camera any time in the near future:

In his blog post, he points out that plenty of other great videos has been shot on DSLRs. For example, Kendy Ty shoots mostly with a T2i, and has produced some impressive-looking work:

Simon says something in this video that really gives me pause: "I don't want the most exciting part of my week to be taking a product out of its box." That hits at the core of something that I, and probably countless other people, have struggled with constantly, and in far more aspects of life than just filmmaking.

The truth is that we lust after new gear because we like the way it makes us feel. It feels good to imagine ourselves creating great work. And more than that, it feels good to imagine that whatever self-imposed psychological barrier that is preventing us from creating work has been overcome through the simple act of purchasing something new. The only problem is that once new gear comes out of the box, you quickly realize that it's not the panacea you were hoping for. It, like the camera you already own, is still just one very small piece of the much larger puzzle which is filmmaking.

And I think that's the problem. The process of making a film can be incredibly overwhelming, especially with small crews and tiny budgets. So, when it comes time to actually make something, it's easy to make excuses like, "Oh I should wait until I have more professional gear." It's a defense mechanism against having to immerse ourselves in a process that is not only daunting and tedious, but which could very well turn out to be a waste of time if the product doesn't turn out like we imagine it in our heads.

From my experience, projects never turn out exactly as you hope they will. There are always obstacles — some technical, some monetary, and some psychological — that get in the way. The only answer is that you have to love the process of making a film. If you can learn to love the process (and it is something that you have to learn), it doesn't matter what gear you have because you're immersing yourself in something that is inherently enjoyable. When you love the process, gear becomes a side note. It still matters, but it's been taken off of the pedestal, and it becomes just another piece of the filmmaking puzzle.

That, my friends, is how we defeat Gear Acquisition Syndrome once and for all.

AEP : 30 Things British People Say Vs What We Actually Mean. #9 Is Perfect.

Share this with your friends by clicking below!

Share this on Facebook

AEP : See Seinfeld recut as a Lifetime movie, then realize life is about nothing

Albener PessoaThe trailer : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AX7UXqVRLbk

This is what happens if you re-edit Seinfeld's seventh and eighth seasons to look like a preview for a terrible movie.

It is profound.

The resulting film, called George, centers on a heartbroken man named George Costanza, whose fiancée, Susan, dies due to a tragic envelope-licking accident. As George seeks to pick up the broken pieces of his life, he seeks encouragement from his closest friends, bonds with a young boy whom he feels a special connection with, and, finally, learns to find grace in a world that, so often, is as cruel as a batch of bad envelope glue.

This will make you love Seinfeld again and, as importantly, realize just how crazy it was that the most popular sitcom in the country spent a year mining comedy from a dead fiancée. Macabre was mainstream.

The best line in the trailer might be Jerry's, when he wisely advises George, "Her death takes place in the shadow of new life; she's not really dead if we find a way to remember her." You suddenly wonder whether Jerry was a profound philosopher — until you remember it's a quote from Wrath of Khan.

NSA Plans for a Post-Quantum World

Quantum computing is a novel way to build computers -- one that takes advantage of the quantum properties of particles to perform operations on data in a very different way than traditional computers. In some cases, the algorithm speedups are extraordinary.

Specifically, a quantum computer using something called Shor's algorithm can efficiently factor numbers, breaking RSA. A variant can break Diffie-Hellman and other discrete log-based cryptosystems, including those that use elliptic curves. This could potentially render all modern public-key algorithms insecure. Before you panic, note that the largest number to date that has been factored by a quantum computer is 143. So while a practical quantum computer is still science fiction, it's not stupid science fiction.

(Note that this is completely different from quantum cryptography, which is a way of passing bits between two parties that relies on physical quantum properties for security. The only thing quantum computation and quantum cryptography have to do with each other is their first words. It is also completely different from the NSA's QUANTUM program, which is its code name for a packet-injection system that works directly in the Internet backbone.)

Practical quantum computation doesn't mean the end of cryptography. There are lesser-known public-key algorithms such as McEliece and lattice-based algorithms that, while less efficient than the ones we use, are currently secure against a quantum computer. And quantum computation only speeds up a brute-force keysearch by a factor of a square root, so any symmetric algorithm can be made secure against a quantum computer by doubling the key length.

We know from the Snowden documents that the NSA is conducting research on both quantum computation and quantum cryptography. It's not a lot of money, and few believe that the NSA has made any real advances in theoretical or applied physics in this area. My guess has been that we'll see a practical quantum computer within 30 to 40 years, but not much sooner than that.

This all means that now is the time to think about what living in a post-quantum world would be like. NIST is doing its part, having hosted a conference on the topic earlier this year. And the NSA announced that it is moving towards quantum-resistant algorithms.

Earlier this week, the NSA's Information Assurance Directorate updated its list of Suite B cryptographic algorithms. It explicitly talked about the threat of quantum computers:

IAD will initiate a transition to quantum resistant algorithms in the not too distant future. Based on experience in deploying Suite B, we have determined to start planning and communicating early about the upcoming transition to quantum resistant algorithms. Our ultimate goal is to provide cost effective security against a potential quantum computer. We are working with partners across the USG, vendors, and standards bodies to ensure there is a clear plan for getting a new suite of algorithms that are developed in an open and transparent manner that will form the foundation of our next Suite of cryptographic algorithms.Until this new suite is developed and products are available implementing the quantum resistant suite, we will rely on current algorithms. For those partners and vendors that have not yet made the transition to Suite B elliptic curve algorithms, we recommend not making a significant expenditure to do so at this point but instead to prepare for the upcoming quantum resistant algorithm transition.

Suite B is a family of cryptographic algorithms approved by the NSA. It's all part of the NSA's Cryptographic Modernization Program. Traditionally, NSA algorithms were classified and could only be used in specially built hardware modules. Suite B algorithms are public, and can be used in anything. This is not to say that Suite B algorithms are second class, or breakable by the NSA. They're being used to protect US secrets: "Suite A will be used in applications where Suite B may not be appropriate. Both Suite A and Suite B can be used to protect foreign releasable information, US-Only information, and Sensitive Compartmented Information (SCI)."

The NSA is worried enough about advances in the technology to start transitioning away from algorithms that are vulnerable to a quantum computer. Does this mean that the agency is close to a working prototype in their own classified labs? Unlikely. Does this mean that they envision practical quantum computers sooner than my 30-to-40-year estimate? Certainly.

Unlike most personal and corporate applications, the NSA routinely deals with information it wants kept secret for decades. Even so, we should all follow the NSA's lead and transition our own systems to quantum-resistant algorithms over the next decade or so -- possibly even sooner.

The essay previously appeared on Lawfare.

EDITED TO ADD: The computation that factored 143 also accidentally "factored much larger numbers such as 3599, 11663, and 56153, without the awareness of the authors of that work," which shows how weird this all is.

EDITED TO ADD: Seems that I need to be clearer: I do not stand by my 30-40-year prediction. The NSA is acting like practical quantum computers will exist long before then, and I am deferring to their expertise.

AEP : TV and the Flynn Effect

Ever notice that old tv shows and movies are boring? Why should this be? Were people more easily entertained thirty years ago? Were they dumber? Why yes, they were.

IQ test scores have been increasing over time, a fact known as the Flynn effect. No one knows exactly why but some ascribe the effect to the greater cognitive demands of modern life. Writing in the NYTimes Magazine Steven Johnson provides some interesting evidence from television. He argues, I think correctly, that the plot structure of television dramas from a generation ago are much simpler than modern equivalents.

The following graph illustrates a typical Starsky and Hutch episode:

The x axis indicates time and the y axis different plot-threads – the opening and closing points are the little "aha" that brings the story full circle with a little comedic twist.

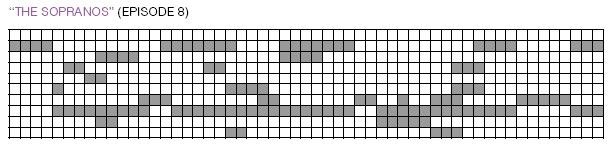

Compare with the Sopranos in which plot-threads and characters interweave across many different episodes:

Is it any wonder that modern viewers are bored by older television?

Johnson wants to argue that the changes in television are part of what is causing the Flynn effect (he doesn’t say this explicitly in the NYTimes article for that you have to read his piece in the April Wired (not yet online) – very meta.) Of course, it’s difficult to say what is cause and what is effect – probably both are involved. (See Dickens and Flynn for more on that theme.)

I liked Johnson’s argument for a new system of tv ratings. Don’t focus on the content focus on the complexity of the content’s presentation.

Instead of a show’s violent or tawdry content, instead of

wardrobe malfunctions or the F-word, the true test should be whether a

given show engages or sedates the mind. Is it a single thread strung

together with predictable punch lines every 30 seconds? Or does it map

a complex social network? Is your on-screen character running around

shooting everything in sight, or is she trying to solve problems and

manage resources? If your kids want to watch reality TV, encourage them

to watch ”Survivor” over ”Fear Factor.” If they want to watch a

mystery show, encourage ”24” over ”Law and Order.” If they want to

play a violent game, encourage Grand Theft Auto over Quake.

Addendum: Ted Frank points out that cable television has added to the phenomena, by fragmenting viewers it has allowed higher quality (less common denominator) content to filter through.

AEP : Would you use this for baby soft skin? Chinese mother makes soap from her BREAST MILK as gifts for friends

Albener PessoaWTF ?

- Woman, named only Ms Qi, from Wuhan, is new mother to four month old

- Made 110 bars of the soaps out of excess breast milk and gave them away

- Breast milk soap trend began in Taiwan and is becoming hot in China

A Chinese mother has made a truly unique present for her friends.

The woman, named only by her surname Qi, has recently created hand-made soap out of excess breast milk, reported People's Daily Online.

She has been making the soaps since the beginning of August in Wuhan, central China.

New mother from Wuhan, China, has started making soaps out of excess breast-milk for friends (file photo)

Breast milk soap has become a big trend in China. Above, a batch of soap made by another unnamed woman

Photographs of her gifts were shared by a close friend and caught wide-spread attention online.

According to reports, the new mother's baby is just four months old.

She was producing too much milk for her baby so decided to create the soaps.

The mother then spent 10 days to stock up more than 10 litres of her breast milk.

She bought a soap-making kit from the internet, after reading up the production process online, and made 110 bars of the breast milk soap for friends.

Close to 1,000 online retailers are said to be selling the breast milk soaps including the above from Ena's Soap

Ready-made breast milk soap, like the one pictured above, is sold for around 1,200 Taiwanese Dollar (£23.63) for 1kg by Ena's Soap

Ena's Soap's products come in several designs. In China, many breast milk soaps are shaped into flowers, hearts and Hello Kitty

Ms Qi claims that breast milk soaps are quickly becoming a new trend in China.

The trend had originated in Taiwan with Taiwan Breast Milk Association leading the way.

Recipes for the soaps could be found on the association's website dating as far back as 2005.

There are currently close to 1,000 online outlets in China selling either breast milk soaps or soap-making kits.

Many of the breast milk soaps are shaped into flowers, hearts and Hello Kitty.

Ms Qi says that the soaps not only mark the first time a woman becomes a mother but is also a nice gift for friends.

A recipient of the gift, named only as Ms Ding, said: 'This is the most unique gift I've ever seen'.

Online retailers of the unusual soap claim that, as well as being used for cleansing, the soaps will make your skin softer and is naturally beautifying.

However, there are health and safety concerns about the use of the soaps too.

Recipes for the soaps could be found on Taiwan Breast Milk Association's website dated from 2005 (file photo)

Director of obstetrics at Affiliated Hospital of Wuhan University of Science and Technology, Dongrui Qing, has revealed there are three key considerations when using breast milk soaps.

The first is that as breast milk is a body fluid, it can easily harbour blood-borne diseases.

This means that a new mother should be certain that she is fit and healthy with no medical conditions that could affect the quality of her milk.

During the preparation of the soap, the milk should also be kept at a low temperature and in sterilised, sealed containers in order to reduce spoilage.

Finally, pregnant women and children should avoid using the soaps as they are more susceptible to any diseases that could be passed on.

From the comments — on suicide

Switzerland tolerates assisted suicide since 1942 and there are very interesting numbers. A) From 1995 to 2009, assisted suicide cases have grown but the total number of suicides keeps constant. B) Assisted suicide in 2009 accounted for approx 30% of all suicides. C) Women chose assisted suicide more than men, but men use firearms more than women to commit suicide. D) Peak assisted suicide is between 75 and 84 years old. It seems that people that cross the 80+ years old line are not affected by painful or exhausting diseases thus they choose to life until it ends naturally E) Peak suicide is between 45-54 years old, midlife crisis is real, F) Overall suicide rates for women kept constant even if assisted suicide rates increase. G) Overall suicide rates for men are going down and assisted suicide goes up.

http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/en/index/news/publikationen.html?publicationID=4732

The overall suicide rate in Netherlands between 1999 and 2013 has been between 8.3 and 11 per 100K habitats. The lowest rate was just before the crisis. http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/themas/gezondheid-welzijn/publicaties/artikelen/archief/2015/4320-suicide-in-noord-holland-noord-en-nederland1999-2013.htm

The WaPo article would lose its killer headline if the total suicide rate is considered when assessing the “exponential” increase of assisted suicide. This seems like another case of double standards. When someone blows their brains with a gun we have to respect the decision and comfort the family, when someone opens the valve of sodium thiopental with their hand…..it’s just wrong.

That is from Axa.