Read the first three issues of Kid Mafia online, for free:

http://kingtrash.com/kidmafia/readkidmafianumberone.html

http://www.kingtrash.com/kidmafia/2/kidmafiatwo.html

http://www.kingtrash.com/kidmafia/3/kidmafiathree.html

Issue 4 out this summer.

Read the first three issues of Kid Mafia online, for free:

http://kingtrash.com/kidmafia/readkidmafianumberone.html

http://www.kingtrash.com/kidmafia/2/kidmafiatwo.html

http://www.kingtrash.com/kidmafia/3/kidmafiathree.html

Issue 4 out this summer.

Taylor SwiftYES!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! YES YES YES YES YES

Stainless steel beanbags from ”Stable Inhabitants of a Changing World” series by Cheryl Ekstrom via Trove.

Taylor SwiftLmao come on

^ Empire II, as featured in Dubai-based Brusselssprout Curatorial Magazine #2 [Fall 2010]

‘Empire II is the continuation of Empire.

On Saturday 25 July 1964 (46 years ago) Andy Warhol and Jonas Mekas filmed the movie Empire.

Empire is a silent, black and white film that lacks a traditional narrative or characters. The passage from daylight to darkness becomes the film’s narrative, while the protagonist is the iconic building that was (and is again) the tallest in New York City. Non-events such as a blinking light at the top of a neighboring building mark the passage of time.

It was filmed from 8:06 p.m. to 2:42 a.m. from the 41st floor of the Time-Life Building, from the offices of the Rockefeller Foundation.’

Empire II is the continuation of the Andy Warhol work: creation of non-media as media, film as non-film. The film was shot on July 27th, 2010 by Andre Orione, David Payton and Lohra Ydna and presents Burj Khalifa (aka Burj Dubai).

Taylor SwiftCOME ON

The Boston Licensing Board holds a hearing tomorrow to figure out what to do about Uncle Crummy's, shut by police in January as part of a crackdown on unlicensed music venues in Allston and Brighton.

Peter Gallagher, listed as the operator of the place at 30 Penniman Rd., has to answer to charges he violated state law by running a night club out of a residence, selling beer and shirts, charging a cover charge and having a live band play, all without any licenses. He was cited after a police raid on Jan. 10, when Ramming Speed and Sexcrement were scheduled to play.

Board hearings start at 10 a.m. in its eighth-floor hearing room in City Hall.

Performance at Uncle Crummy's the week before it was shut:

Taylor SwiftOMG OMG OMG OMG OMG OMG OMG OMG

Taylor SwiftYESSSSSSSSSSSS

Oil on linen works by Adam Sorensen (Born: 1976, Chicago, IL) whose show just concluded at PDX Contemporary Art in Portland.

Taylor SwiftSnake............ SNAAAAAAAAAAAKE :-(

David Hayter, the longtime Metal Gear voice actor, wrote a post on Twitlonger today explaining how he learned that he won't be reprising his role in Metal Gear Solid 5, the upcoming installments in Hideo Kojima's tactical stealth action series.

Hayter has portrayed various incarnations of Snake in the nearly 15 years since 1998's Metal Gear Solid release. When he returned home from Toronto for the holidays last year, he learned that the recording sessions for Metal Gear Solid 5 were "being put together." After he made contact "with someone involved with the production," he was told that they "wouldn't be needing" him.

"If it were my choice, I would do this role forever," Hayter wrote. "To hear anyone else's voice coming from Snake's...

There’s nothing wrong with masturbation. But this book tells you to jack off while you read it, to specific situations like a teacher being proud of you, or doing well at work. And you can’t just crank it a little and turn the page. You have to finish the job. To every single page of the book. Read the “Click To Look Inside!” to see what I’m talking about.

(By the way, this is not the first product I’ve written about where I’m 99% sure the creator thought of the title first.)

[source: Out of Sight, Out of Mind]

‘Since 2004, the US has been practicing in a new kind of clandestine military operation. The justification for using drones to take out enemy targets is appealing because it removes the risk of losing American military, it’s much cheaper than deploying soldiers, it’s politically much easier to maneuver (i.e. flying a drone within Pakistan vs. sending troops) and it keeps the world in the dark about what is actually happening. It takes the conflict out of sight, out of mind. The success rate is extremely low and the cost on civilian lives and the general well-being of the population is very high. This project helps to bring light on the topic of drones [...].’

Taylor SwiftStopping by tomorrow. This rules real fuckin hard.

Pete and Nick, from Guerilla Toss and Cave Bears respectively, have opened up a wild new record shop near the Forest Hills T station in JP! It’s called DEEP THOUGHTS JP (and yes that is a Jack Handey reference). Here’s their self described run down:

RECORDS / TAPES / CDs / BOOKS

noise/psych/punk/krautrock/synth/weird/classic/indie

NEW / USED / RARE / LTD. EDITION

free jazz/prog/international/folk/blues/soul/cheap !!!

BUY / SELL / TRADE / SCHMOOZE

in-stores / listening parties /dj nights / art shows

Go now!

Spend time and dollars at this store. Make it your epicenter when in JP. JP needs this place bad. Boston in general needs more places like this. Much love and best of wishes. If they can do we all can do it (and Boston Hassle can gets its performance venue open)! LONG LIVE THE JP RECORD SHOP KNOWN AS DEEP THOUGHTS JP.

The post CRUCIAL BOSTON INFO: DEEP THOUGHTS JP Record Shop is OPEN appeared first on The Boston Hassle.

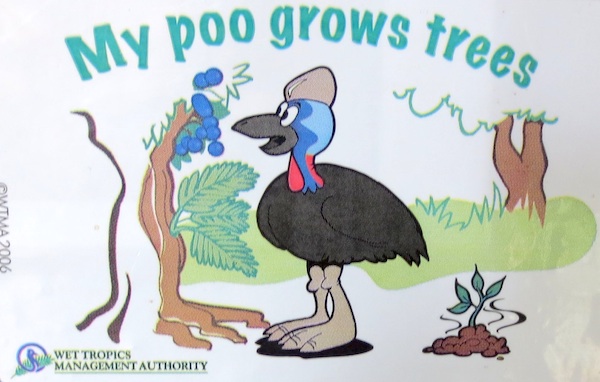

The cassowary is a two-meter high bird with a large horn on its head, cankles, a red wattle, and a bright blue neck. The fact that it is well-camouflaged in the Australian rain forest tells you something about this remarkable habitat.

Every so often a nature show tries to bill the cassowary as ‘the most dangerous bird in the world’, and even though this is technically true, it's a little disingenuous. Northern Queensland makes a lot of competing demands on your fear. From old classics like the paralysis tick, salt-water crocodile, and box jellyfish, to hungry young newcomers like the the flesh-eating Daintree ulcer, the Daintree rainforest has a deep bench. And even though the cassowary has giant slashing blades on its feet, and is powerful enough to disembowel a person with one kick, it's clear that the bird's heart is not in it. It just wants to eat fruit and be left alone. There are plants in Daintree (read on!) scarier than the cassowary.

Most mornings in Port Douglas I go down to the wildlife center to watch Cassie the cassowary eat her breakfast, a large bowl of fruit that has been laid out for her by the volunteer staff. She stands above it with quiet dignity, dipping her head occasionally to grab another piece. There are two cassowaries at the center, both left free to roam in the semi-open enclosure. Cassie prefers to stand by the door, while Ayerlie likes to hang out under the raised walkway, startling passers-by by poking her head out near their feet. The cassowary has an unnerving stare. Like its relative the emu, it fixes you with giant, unblinking eyes (framed by gorgeous lashes!) with an intensity that makes you wonder if it is having second thoughts about a fruit-only diet.

Cassie is less interested in passers-by, perhaps because of her high-profile station near the entrance. It's amusing to watch visitors react as they come out the screen door and see the enormous, blue-necked creature grooming its long black feathers just a few steps away. The cassowary's feathers are so long and fine they look almost like fur. Once in a long while, Cassie lets out a seismic, almost inaudibly low growl that sounds like a fair-sized motorcycle gang revving up just over the horizon. You feel it more in your chest than hear it. This is the bird's territorial call, and the casque on her head serves as an amplifier, making it easier for it to her to hear the same low frequencies at a distance ①. Infrasound penetrates the thick forest much more easily than sounds of a higher pitch. The growling completed, she settles down carefully, folding her legs under her, and rests for a while on the ground like a giant hen.

Being mobile and solitary, the cassowary has a hard time adjusting to the modern human presence in Australia. For the last three centuries, non-indigeneous Australians have been hypnotized by the idea that, with enough spadework, this fascinating continent could be made to look like Dorset. The result everywhere has been catastrophic, but it is especially pitiful here. One of the richest habitats in the world has been cleared to make way for vast fields of sugar cane ②. More recently the Queensland authorities have designated ‘cassowary corridors’, or links between remaining patches of rain forest, to allow the birds to wander. It takes quite a bit of territory to satisfy a cassowary, and even more territory to give it a chance at finding a suitable mate. To get from one patch of forest to another means crossing busy roads, and the biggest threat to the southern cassowary (which has no predators) is the automobile. Speed bumps and cassowary crossing signs don't deter visitors from barreling along rain forest roads at high speed.

To the cassowary, the Daintree rain forest is a big, year-round buffet. Like coffee hipsters who won’t touch beans that have not first passed through a civet cat, some plants in Daintree won't even germinate until their seeds have transited a cassowary. The bird's nitrogen-rich turds give seedlings a huge advantage in the race for the canopy, and like doting parents frantic to get their children into Harvard, plants will go to great trouble to get their fruit into a cassowary. The itinerant and hungry bird is happy to oblige, eating its fill under a variety of trees that have specialized in making it happy, then walking several kilometers until it's timefor another feast. It deposits new generations of fruit trees as it goes. The cassowary eats, the plants grow, and both sides of the arrangement are happy. ③

This struggle for canopy is a feature of any forest, but it is unusually murderous in the tropics, where water and sunshine are abundant and there is no winter break. The first task of any seedling is to break through into sunlight, and plants will resort to desperate measures, including climbing all over their rivals until one or the other collapses under the weight. The rain forest only looks peaceful because we see it at a human time scale, and fail to notice the slow-motion deathmatch.

Given the effort they expend to attract cassowaries, plants look dimly on any third parties that try to crash the fruit party, especially third parties who can't be trusted to pass the seeds whole. Unfortunately for us, they solve this free-rider problem with poison. Despite the enormous diversity in species, and the abundance of fruit, there is almost nothing safe in the forest for people to eat. Through what one imagines to have been a miserable series of experiments, the aborigines have worked out protocols for how to eat some of this stuff without dying. There is a nut, for example, that if you cut it into thin wafers, wrap them in a cloth, leave the bundle suspended in a stream for three days to leach out the poison, pound it into a mash, and take care not to eat more than a small fingerful at one sitting (so you don't go blind), is edible. These are the snack options available in Daintree.

The rain forest finds other ways to be unwelcoming. The first plants to grow after a space has been cleared tend to be particularly awful, which means footpaths and sunny clearings are some of the more hazardous places to walk in the forest. My favorite of these pioneers is the vegetable kingdom’s shout-out to the nearby box jellyfish, a plant the normally unflappable Australians have named the ‘stinging tree’. Nomen omen. The stinging tree is covered in a myriad of tiny glass spines that embed themselves in your skin at the slightest touch. And because we are talking about Australia, the glass is coated in neurotoxin. The wound will keep hurting for weeks, and then it will start to itch.

My Aussie friend describes leaning against such a tree trunk with his hand to catch his balance, realizing only too late that it was an oversize stinging tree. It was a week before he could touch anything, and two months before his hand finally felt normal. The first night he spent an interesting evening with tweezers and a bottle of whisky. The recommended treatment, he learned later, is a depilatory wax strip. Given the amount of pain involved, it's fortunate that he didn't have access to a machete.

The stinging tree is not without a sense of humor. Its bright red fruit, if you can think of a way to remove the neurotoxic peach fuzz, is one of the few edible fruits in the forest.

Another way to pass some time in the sunny parts of Daintree is by hooking yourself on the lawyer vine, or wait-a-while. These beautiful names give you a sense of just how many thorns cover this aggressive, creeping vine. It catches on absolutely everything and uses its powers of attachment to climb up other plants (a standard strategy in the rain forest) towards the canopy, eventually crushing them under its own weight. Up close it looks a lot like a burr, if you have ever seen a burr dozens of meters long and as thick as a banana.

The final joke the Daintree rain forest plays on people isn’t obvious to the casual visitor, but catches many hikers unaware. Despite the name, it can be difficult to find fresh water when it’s not actively raining. And when it does start to rain, it rains torrentially, and you are liable to find your legs covered in leeches. Daintree takes its rain seasonally, during the period from December to April known as the ‘Big Wet’, and at other times hikers struggling up the Mount Sorrow trail have found themselves stranded in the dark, miserable and dessicated, surrounded by poisonous fruit and loud, mocking birds.

Until recently, a cassowary named Elvis guarded the approach to Mount Sorrow like some kind of bridge troll, preventing many people from even attempting the hike. This uncompromising bird patrolled the beach at the trailhead, holding one couple hostage for forty minutes, and on another occasion surprising an Indian tourist with a kick from behind as he photographed a sunset. The Port Douglas gazette reports, with a straight face, that the poor man “ran into the safety of the water”. His further fate is not recorded.

Elvis was eventually trapped and deported to some more remote part of Daintree, exiled for the crime of taking the fight too aggressively to The Man. The forest has been further defanged in a couple of places where biologists have set up ground-level boardwalks and elevated walkways that take you through the canopy. The view from these is spectacular. Very little of what goes on in this forest is visible from ground level, and the catwalks give a sense of just how specialized every plant and animal becomes in such a rich habitat. The view from up high, along with explanatory placards, also tips you off to the Daintree's big secret.

It turns out that this is one of the oldest ecosystems on the planet. I remember marveling when I visited Poland's last stretch of primeval forest that the patch had existed uninterrupted since the glaciers retreated from Central Europe 12,000 years ago. But the Daintree rain forest has been around for 180 million years, about ten thousand times as long. Before there was an Australia, before there were flowering plants, or cassowaries to eat their fruit, this forest was already growing. Through a fluke of geology and climate it has persisted all the way into our era, along with a selection of giant ferns and other relic plants found in no other part of the world. It is humbling to be in a place that predates not only your species, but your genus, family, and order, and remembers your class when they were just a bunch of scurrying, trembling little dinosaur treats. Given its incredible antiquity, it doesn't seem fair that we should now have the power to decide this forest's fate, but here we are.

① There is controversy over the cassowary's casque. The leading theories are that it is a simple case of sexual selection (like the peacock's tail) with no practical function, that it is a kind of crash helmet to protect the bird as it runs head-down through the forest, that it protects the bird's head from falling fruit, or that the cassowary uses the casque to dig through leaf litter. With great tact, the biologist Andrew Mack has pointed out that cassowaries do not run with their heads down, and that they invariably use their feet, rather than their heads, to rake through leaf litter. He implies but does not say outright that some of his fellow theorists might benefit by spending, say, ten minutes watching an actual cassowary rather than Road Runner cartoons. Mack does not exclude the possibility that the casque is just a sexual ornament, but he finds the fact that it is ideally structured to amplify sound at low frequencies, and connected to the bird's inner ears, provocative.

② Farmers and fishermen in Australia test the limits of human empathy. While I was in Cairns, for example, controversy ranged around the recent extension of the Great Barrier Reef marine park, opponents arguing that the expanded ban on fishing would harm the Cairns fishing industry, and proponents arguing that that was the whole goddamn point. If it were up to Australian farmers and fishermen, the Great Barrier Reef would be processed into bags of fish meal, the fish meal spread as fertilizer on land obtained by clearing the remaining rainforest, the fertilized land used to grow sugar, and the sugar used as raw material for some of the least appetizing desserts in the world. The fundamental question is this: do we prefer our biomass in the form of gorgeous reef and rain forest ecosystems, or Australians? Unfortunately, the only country that has any say in the matter is also the only one that finds the question hard to answer.

③ This approach to spreading seeds by making tasty fruit for large animals to swallow whole is very common (the technical name for it is megafaunal dispersal syndrome). It worked wonderfully until human beings began to spread out of Africa, hunting large animals on every other continent into extinction. And so we live in a world full of fruits—avocado, mango, papaya, honey locust, osage orange, gingko—whose seeds are designed to be pooped out by large animals, but who have been left without their animal partner. In this respect, the trees of northern Queensland are lucky to still have the cassowary. See The Ghosts of Evolution for the full, fascinating story.

“Truck simulation games are definitely very niche, and indeed historically such games have always been the target of ridicule among hardcore gamers, much more so than flight simulators or train simulators for understandable but not so simple reasons,” Sebor says.

“Perhaps the fact that our games may be ridiculed in the UK but loved in Eastern Europe is down to the fact that a trucker may be considered a low-prestige job in the UK (and a target of Jeremy Clarkson [Top Gear presenter] jokes),” he reasons.

The further East you go, he notes, “the more this job smells of adventure and distant horizons - plus it’s perhaps paying better than average in those countries.”

–Interview with the Developers of Euro Truck Simulator 2

Taylor SwiftATTN: ALLIE

Full of tightly constructed and arranged pop nuggets of a spastic nature, PRETTY & NICE here return with a new tape entitled US YOU ALL WE. Their warped new wave meets glam meets modern SUB POP style pop rock is intact and these four songs whizz by, implanting their hooks deep in your noggin along the way whether you like it or not. And I definitely lean much more toward the liking it side of things. Each song clocks in at under 3 minutes, but each is a journey through herky jerky guitar led verses, big harmonies, memorable choruses, and sudden shifts in unexpected directions. Super inventive pop, like little else we are hearing in Boston or anywhere in New England for that matter. “Hibernate” seems like a classic New England minded ode to resting, and coming back with more vigor than before, and it’s all wrapped up in a bopping pop package featuring the aforementioned twists and turns and soaring vocal melodies. For those of you among us who appreciate pop songwriting as the art form it can be, have a listen won’t you?

The post FRESH STREAM: PRETTY & NICE appeared first on The Boston Hassle.

Murakami Saburo, “Passing Through” (1956). Performance view at the 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition, Ohara Kaikan, Tokyo, c. October 11–17, 1956. (click to enlarge) (© Murakami Makiko and the former members of the Gutai Art Association, courtesy Museum of Osaka University)

Fifteen years in the making, the current Guggenheim exhibition on Gutai presents a groundbreaking spectrum of the art of that group, shaking to its core the notion of the West as the epicenter of contemporary art practices. The show, curated by Ming Tiampo, associate professor of art history at Carlton University, Ottawa, and Alexandra Munroe, senior curator of Asian art at the museum, is titled Gutai: Splendid Playground, an odd sobriquet to describe the annihilating force that birthed the group in postwar Japan. They held together for 18 years, from 1954 to 1972, as a coterie of roughly 59 artists grappling with the annihilation of the past, but also, in their later phase, looking towards the glories and hidden trappings of a imagined technological future. No movement was more primal than Gutai (which translates as “concreteness”), for no other culture on earth had been incinerated by the nuclear bomb. Rising phoenix-like from the ashes of Allied occupation, they upended convention through remarkable developments in painting, performance, installation, experimental film, and sound, kinetic, light, and environmental art.

Shiraga Kazuo, “Challenging Mud” (courtesy McCaffrey Fine Art)

Collective artists’ organizations, called bijutsu dantai, had a long history of state sponsorship in Japan, but they tended to squash innovation. The Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai, or Gutai Art Association, based in Ashuya, near Osaka, was founded in 1954 by 49-year-old painter Yoshihara Jiro, a George Maciunas-like figure who mandated, “Never imitate others — make something that has never existed.” Using the loose structure of the dantai, Yoshihara chose younger artists open to new ideas to populate his association. As with the art movements of Dada and Fluxus, the members of Gutai issued a manifesto published in the art journal Geijiutsu Shincho:

These objects are in disguise and their materials such as paint, pieces of cloth, metals, clay or marble are loaded with false significance by human hand and by way of fraud, so that, instead of just presenting their own material, they take on the appearance of something else. Under the cloak of an intellectual aim, the materials have been completely murdered and can no longer speak to us.

Lock these corpses into their tombs. Gutai art does not change the material but brings it to life. Gutai art does not falsify the material. In Gutai art the human spirit and the material reach out their hands to each other, even though they are otherwise opposed to each other.

By January 1, 1955, the group began publishing the Gutai Journals of their artworks, essays, photographs, and documentation of outdoor and stage pieces, one of the few ways anyone outside of Japan knew of their existence. Copies found their way to Europe, the US, and even South America. In 1956, artist Shimamoto Shozo enclosed copies of the magazine in a letter to artist Jackson Pollock. The composer Earle Brown and his wife, dancer Carolyn Brown, avidly collected the journals, sharing them among their avant-garde circle of friends. Gutai 6 even published a spread on Pollock in both English and Japanese. By 1958, the group had gained enough traction to stage the 6th Gutai Art Exhibition at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York — and was resoundly dismissed. Critic Dore Ashton wrote in the New York Times that they were “ineffectual” and derivative of “Pollock followers.” A few astute artists, including Paul Jenkins and Allan Kaprow, who included them in his book on Happenings, begged to differ. Yoshihara later quipped to his Western critics that Gutai artists did not favor the expectation of “Orientalism” in their work.

Motonaga Sadamasa, “Work (Water)” (1956–2011), in the Guggenheim Rotunda (courtesy the Guggenheim Museum)

The current Guggenheim exhibition contains 145 works by 25 artists and begins in the museum’s rotunda with a luscious sculptural installation by the late Motonaga Sadamasa titled “Work (Water),” which employs long, thin, clear industrial plastic tubes weighted by colored water and suspended from the coiling inner spirals of the museum’s walkway.

The Gutai constantly combined materials with the urgency of alchemists, as if by conjuring matter in original ways art could somehow banish man’s inhumanity to man. “Disregarding the frame getting off the walls, shifting from immobile time to lived time, we aspire to create a new painting,” they declared, using sawdust, gravel, dirt, newspapers, glass, their feet, gravity, hot tar, nails, oil, boar hide, and spent bullets as painting materials. Shiraga Kazuo, in the Art Using the Stage show, swung from a rope and paint with his bare feet, a process he called “Sambaso Super Modern”; he said he wanted to make work “as slippery … as a sea cucumber.” One of the revelations of the Guggenheim exhibition is its display of faded videos of his (and others’) process, where one can actually watch his messy, slippery, balletic glide over the canvas.

Shozo Shimato painting with his feet (via Studyblue.com)

Kanayama Akira squirted paint from an electric toy car, and others wore deep-sea goggles while hurling bombs of pigment. Another approach favored brutally singeing fire onto scorched wooden planks or, in one case, actually burning an entire ouvre. Long before Julian Schnabel’s canvases of smashed plates, Shiraga Fuijiko combined oil, synthetic paint, shards of glass, and paper on canvas. Shimamoto Shozo, too poor to buy canvas, painted on layers of newspaper with glue, leaving gaping holes in the picture plane. Matsutani Takesada used synthetic paint and adhesive to redefine the whole idea of painting and plasticity. But the show-stopping piece is 1955′s “Challenging Mud,” which featured an almost naked Shiraga Kazuo kicking and thrashing in the mud, using his entire body as the brush. It forever broke, in one grimy swoop, the barrier between performance and painting. By 1971, Shiraga was ordained as a Buddhist monk at the Enryaku-ji Monastery on Mount Hiei near Kyoto, taking the simple name Sodo, but he continued to paint until his death.

Tanaka Atsuko, “Electric Dress” (1956) (via Medienkunstnetz.de)

There were women in Gutai, most notably Tanaka Atsuko. She first premiered her barely wearable “Electric Dress” in 1957 at Sankei Kaikan Hall in Osaka; as it heated up, it threatened to short circuit and to electrocute her. The dress was so dangerous she could only wear it in five-minute intervals. Tanaka also produced the inventive “Stage Clothes,” peeling off successive layers of clothes, under which were endless layers of yet more garments, and “Work (Yellow Cloth),” a radical intervention for which she procured squares of yellow dyed fabric and mounted them as paintings in a gallery, something only Kazimir Malevich and Robert Rauschenberg dared, with their white paintings on white. She then made a film of drawing circles in the sand, an environmental art piece before it became the fashion, and continued the theme of circles with her multiple canvases of circular shapes.

As the critical issues of postwar Japan receded, the Gutai moved from nihilism to exploring the rapid and dehumanizing industrialization and mechanization that accompanied Japan’s economic rejuvenation. Member Joji Kikunami declared:

In order to do something truly human it is imperative that our entire civilization undergo a fundamental transformation, and we should improve human nature individually within social networking our understanding of science and science’s capacity.

In 1962 at the Takashimaya department store in Osaka, the 11th Gutai Art Exhibition showcased the whimsical “Gutai Card Box,” an interactive vending machine with an artist standing inside the structure. When a participant dropped in a ten-yen coin, he received an original art postcard. (The piece has been refabricated for the Guggenheim show.) ”Gutai Card Box” was constructed to emphasize the increasingly mechanized and alienated environment of daily life and consumption, including the rise of the soulless vending machine. Three years later, Gutai was exhibiting at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam along with the NUL and Zero movements, and it was then that they truly burst onto the scene.

Yoshida Minoru, “Bisexual Flower” (1969) (via Vernissage TV)

Many of the group’s later pieces incorporated sensors, kinetic action, light, sound, and most importantly, robotics, in which Japan particularly excelled. Yoshida Minoru’s motorized purple and green Plexiglas and water sculpture “Bisexual Flower,” from 1969, is one of the biggest surprises at the Guggenheim, having not been widely exhibited. It shows a joyful optimism lacking in Gutai’s earlier works.

Nasaka Senkichiro and Yoshihara Michio, “Work” (1970), stainless steel pipe and recorded sound, approximately 150 meters long. Installation view at the Gutai Group Exhibition, Midori Pavilion, Expo ’70, Osaka, March 15–September 13, 1970. (© Nasaka Senkichiro, Yoshihara Naomi, and the former members of the Gutai Art Association; courtesy Museum of Osaka University)

Caught up in the vigor of the 1960s, the Gutai staged outdoor extravaganzas using helium balloons that lifted actors into the air and made experimental films soaked in vinegar that produced startling Stan Brakhage-like effects on film emulsion. One of Kanayama Akira’s “Balloon” sculptures made vaginal pink inflatable, circular tubes into outdoor environmental sculptures on a hill. In 1967 they took over an amusement park on the outskirts of Osaka and worked with materials relating to rapid industrialization and the imminent space age, playing and forging inroads in optical art.

Expo ’70 Osaka, the first World’s Fair in Asia, marked the beginning of the end for Gutai. They presented “Garden on Garden,” a collaboration directed by Yoshihara, a drama of man and matter, at Festival Plaza under the theme “Progress and Harmony for Mankind,” which highlighted the wonders of modern technology. Nasaka Senkichiro and Yoshihara Michio also presented “Work” (1970), a large metal sculptural installation that incorporated sound. In total, 77 countries participated in the Expo, and over 64 million people attended. Isamu Noguchi, from the US, designed a fountain, and robots were showcased.

Two years later, Yoshihara died, and Gutai disbanded. The era of postwar Japanese reconstruction had come to an end. But now, thanks to this exhibition, Western art history is going to have to go through some serious revisions.

Gutai: Splendid Playground is on view at the Guggenheim Museum (1071 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through May 8.

Taylor SwiftGIE VME THESE

I'm just home from Japan - thanks to an efficient series of buses, trains, planes, and one fabulously upholstered ferry. The trip started in Tokyo, then on to Kyoto, eventually making our way to the incredibly special island of Naoshima. While I get unpacked and settled back in to my regular routine, I thought I'd do a quick round-up of a few of my favorite soups from the archives, the ones that really stood out, the ones I love to revisit. I love a good pot of soup, and (particularly) this time of year, make them a couple times a week. And while the following have become some of my stand-bys, let me know if you have a soup recipe you think I'm missing out on. I'm always on the look-out for new ideas to try. In the meantime, I'll try to pull together some pics and a write up of my plane lunch for later in the week! xo-h

- A Simple Tomato Soup: Pictured here - A simple tomato soup recipe inspired by a Melissa Clark recipe - pureed, warmly spiced, and perfect topped with everything from toasted almonds and herbs, to coconut cream or a poached egg.

- Pumpkin and Rice Soup: This was the pumpkin soup I made first-thing after arriving home from India last October - it has an herby butter drizzle and lemon ginger pulp. I serve it over a good amount of brown rice with a dollop plain yogurt.

- Coconut Red Lentil Soup: If emails are any indication, this is certainly one of the more popular soup recipes with all of you. Inspired by an Ayurvedic dal recipe in the Esalen Cookbook, it is a light-bodied, curry-spiced coconut broth thickened with cooked red lentils and structured with yellow split peas. It has back notes of ginger, slivered green onions sauteed in butter, and curry-plumped raisins. It also relies on an interested cooking method to bring it all together.

- Posole in Broth: My style of posole. This version has a vegetable broth base, lots of blossoming corn kernels, avocado and mung beans. It's topped with plenty of chopped olives and toasted almonds.

- Red Lentil Soup with Lemon: Pictured above here - An earthy, turmeric and mustard-spiked lentil soup served over brown rice with spinach and thick yogurt.

- New Year Noodle Soup Recipe: One of my very favorite soups, a bit of an effort, but well worth it if you have a lazy day at home. This is an amazing New Year Noodle Soup from Greg & Lucy Malouf's beautiful book, Saraban. A bean and noodle soup at its core, it features thin egg noodles swimming in a fragrant broth spiced with turmeric, cumin, chiles, and black pepper. You use a medley of lentils, chickpeas, and borlotti beans which makes the soup heart and filling without being heavy. You then add spinach, dill, and cilantro, and lime juice kicks in with a bit of sour at the end. Even beyond that, you also prep a number of toppings to serve with the soup - chopped walnuts, caramelized onions, and sour cream. Amazing.

- Dried Fava Soup with Mint and Guajillo Chiles: Easily one of the best and most interesting soups I've cooked in years. Adapted from a recipe in Rick Bayless's Mexican Kitchen - a dried fava bean and roasted tomato base is topped with a fascinating cider-kissed tangy/sweet quick-pickled chile topping. Don't skimp out on the topping!

- Green Curry Broth: A beautiful, thin green curry broth, fragrant with garlic, lemongrass, and ginger. It gets heat from serrano chiles, and a zing of tanginess from fresh lime juice. Cumin and coriander seeds keep things grounded, and a flurry of freshly chopped herbs make the sky open up.

- Richard Olney's Garlic Soup : In the realm of garlic soup recipes, this is a favorite of mine. From Richard Olney's The French Menu Cookbook, it is made by simmering a dozen or so cloves of garlic in water with a few herbs, then thickening it with a mixture of egg and shredded cheese. It's hard to beat a ladle poured over crusty day-old chunks of walnut baguette.

Continue reading Soups Worth Making...[B]y the late 1960s, the system began to falter. Buildings were in such a sorry state that buyers were increasingly likely to put $100 down, make a few months of high payments, and then, overwhelmed by the avalanche of expenses necessary to make their new homes livable, abandon the properties. Without steady contract payments, Lawndale's contract sellers had no intention of continuing to pay their own mortgages.In the interest of racism, the American taxpayer ended up bankrolling a massive fraud perpetrated on black communities in Chicago. It gets worse:

Instead, they defaulted on their loans, dumping hundreds of crumbling, overmortgaged buildings back onto the lending institutions. Since the near-ruined buildings were now worth only a fraction of the original loans, the institutions essentially lost their loan money, amounting to millions of dollars. These losses pushed First Mutual to the point of collapse. Desperate to recoup something, the company offered the buildings for sale, at "rock bottom prices," to whoever would take them.

The scavengers who gathered to buy were often the same men who had dumped them in the first place. In one day alone, Moe Forman turned six slums over to First Mutual; five of the six ended up back in his hands, with Gil Balin as copartner. Al Berland dumped approximately sixty buildings onto First Mutual and then repurchased them at a fraction of their former worth.

By 1968, First Mutual was out of business, and 659 of its defaulted mortgages--worth $7.8 million--landed with the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), the governmental agency that insured savings and loan deposits. Many of these debts had been owed by Lawndale's worst contract sellers. They included $756,920 in delinquent mortgages owed by Berke, $280,000 by Berland, $502,323 by Forman's F & F Investment company, $28,945 by Forman himself, and $241,658 by Fushanis's estate.

Some observers found it difficult to understand why Forman and his circle were so eager to reclaim the buildings they had so recently shed. "Slums don't pay. If there was a conspiracy, it was stupid," claimed Pierre DeVise, an urbanologist who taught at the University of Illinois in Chicago. In fact, the "stupid" one was probably DeVise. As the Tribune commented, "Such disbelief ... has been the slumlords' greatest ally." For those ruthless enough to stomach the consequences, it was easy to make profits out of buildings for which one paid cash and on which one owed nothing. As Timothy O'Hara pointed out, "If you're not making repairs ... you are making 100 percent profit."One retort that people often make when discussing the history of racism is "We should not dwell on the past." It's an opportunistic claim--no one looks at July 4 and says "We should not dwell on the past." But more to the point, this is not the distant past. The men and women who suffered at the hands of the FHA and the racist aspects of New Deal legislation are very much alive today. Furthermore, their children are alive and the effects of that policy on the country are fairly obvious. We know what we want to know. We believe the ghetto is manifestation of individual will and amorphous culture values because that is what we would prefer to think. It's not so much that we don't want to dwell on the past, so much as we want to choose our past.

However, O'Hara noted a growing trend among slum landlords: to "avoid paying gas bills until your tenants freeze." Leaving one's building without heat during Chicago's winters was of a different order from refusing to fix faulty wiring or broken windows. It indicated a new phase in their operation, in which the goal was not to get money from tenants but to force them out altogether. For tenants, the results could be lethal. After her nineteen-month-old son, Scott, died of pneumonia, Mary Miller told reporters: "We had to huddle together around the stove and pile on coats and blankets. But it didn't do any good." Every time she complained, "the landlady would say 'If you don't like it get out.'" In the winter of 1969, three babies died over a three-week period because their West Side slum apartments had gone unheated. Their deaths confirmed the insight of the Chicago Tribune's investigative reporters, who noted that, "when someone has to die in this shabby shell game played for money, it is usually a child."

Slumlords' eagerness to rid their buildings of tenants was part of yet another profit-making scheme. It involved the manipulation of the Illinois Fair Plan, which was established in the aftermath of the 1968 riots to ensure that black neighborhoods were covered by fire insurance. As a result of the Fair Plan, buildings in Lawndale were now insurable for the same amount as those on the city's North Side Gold Coast. Slumlords realized that they could insure their rotting, neglected structures for twenty to thirty times what the buildings were worth. Of course, as one observer noted, they "aren't worth anything unless you burn them"--but if you didn't mind arson, then "even an abandoned building could be turned into a $60,000 windfall."

Al Berland didn't mind. By August 1970, fires had broken out in forty-seven of his buildings and he had collected $350,000 in insurance. In one case, a tenant saved the lives of his four children by dropping them one at a time from a second-floor window. In another, Berland and Wolf were observed entering a property they owned at 715 South Lawndale "carefully" carrying some liquid in a bucket. The two men left "in a hurry" and shortly thereafter the building went up in flames. Later that day the police found Berland at his paint store, still wearing the clothing described by a witness. The witness later withdrew from the case "after his car caught fire mysteriously in front of his home." Chicago police sergeant John Moore, an arson expert, said that in his department Berland was known as "a torch."

|

|

Taylor SwiftHELL FUCKIN YEAH

Hi all. The past couple of weeks have been a bit of a whirlwind on this end. I'm (happily) juggling a small handful of projects, all of which I love, but when I find myself setting a google alert for a shower - well, I'm not particularly proud of that. On the cooking front, for the time being, it means I've had to get quite fast and creative in the kitchen. I'm throwing together meals, mostly from the ordinary staples I keep on hand - brown rice, eggs, whatever vegetable is on hand...And yes, some meals are much more successful that others ;) This Kale Rice Bowl, for example, is well worth mentioning. Grains, and greens, and all sorts of goodness going on here. I've been working my way through my last batch of za'atar, and it's part of what makes the bowl special.

You can certainly take this bowl in many different directions if you like. In place of the za'atar, try a different spice blend. On the grain front, I used brown rice, but almost did it with freekah (didn't have time to cook it)....farro would be nice. Or! My original intent was to bake the shredded kale (massaged with olive oil and za'atar), so it had more of a crispy texture, but didn't want to wait for the oven to heat. I ended up sauteing the kale instead. Anyway, play around! xo -h

Continue reading Kale Rice Bowl...Taylor Swiftgod someone PLEASE go to this for me :

Tonight things get spacey in Inman with this dark experimental electronics show. Brooklyn based ZAïMPH is on her way up to LILYPAD and they are bringing slow moving synths with them. Modular synth guru KEITH FULLERTON WHITMAN will peel back your psyche like a ripe onion with his masterly manipulation of the sine wave. PATRICK EMM is all slow buzz and dark samples. Tiny melodic phrases that sound like they are being played on instruments that are pushed to the edge of their capacity, just barely holding on to tonality. Beautiful.

Tonight things get spacey in Inman with this dark experimental electronics show. Brooklyn based ZAïMPH is on her way up to LILYPAD and they are bringing slow moving synths with them. Modular synth guru KEITH FULLERTON WHITMAN will peel back your psyche like a ripe onion with his masterly manipulation of the sine wave. PATRICK EMM is all slow buzz and dark samples. Tiny melodic phrases that sound like they are being played on instruments that are pushed to the edge of their capacity, just barely holding on to tonality. Beautiful.

9pm // All Ages // $10

Live @ Gasometer Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, July 21st, 2012. from Keith Fullerton Whitman on Vimeo.

The post GO TO: TONIGHT (3/17) SLOW BLOOD: ZAïMPH (NYC), KEITH FULLERTON WHITMAN, PATRICK EMM @ LILYPAD appeared first on The Boston Hassle.

Taylor Swift1. This proposal is for the Walgreens being built DIRECTLY UNDERNEATH my office, which, lmao

2. THOSE STATUES I PASS EVERY DAY ARE A "FAMINE MEMORIAL"?????

Walgreens goes before the Boston Licensing Board on March 27 to serve food 24 hours a day at its impending upscale emporium on the site of the old Borders store at School and Washington streets.

According to its application, Walgreens, which plans sushi and juice bars to go with more traditional drugstore fare, is also seeking permission to operate an outdoor patio 24 hours a day, with 24 seats on its own property and 18 extending onto the city sidewalk in front of the Irish Famine Memorial.

Board hearings begin at 10 a.m. in its eighth-floor hearing room in City Hall.