1985. What a year. The Nintendo Entertainment System debuted in the U.S. to near immediate success. What American video game makers had abandoned as a dead market, Japanese video game companies picked up and revitalized. And they began to dominate. Throughout the 1990s, if an award-winning, mind-blowing, landmark game came out, you could bet it was Japanese. Japan’s gilded, diamond-encrusted horn of video game plenty was pouring choice oils of gaming goodness upon us all. And it seemed the flow would never dry up.

2013. Yasufumi Ono made comments about the state of Japanese gaming at the Infinity Ventures Summit in Kyoto. Currently, Japan controls a mere 30% of the market share in North America and only 13% worldwide. The horn of plenty has become a trombone of self-doubt. Why isn’t the world buying Japanese games anymore? Has Japan lost its touch?

There are several factors at play here. When Japan swooped in to grasp the field mouse that was U.S. gaming, that mouse was dead. Thankfully Japan brought the mouse back to life and became the sole devourer of its innards. Today there is more than one falcon-country eyeing those rodent intestines, namely the U.S., South Korea, and Finland.

Also, Japan doesn’t make the games that western countries presently want to play, games in the “Call of Battlefield: Ghost Ops II” category. Japan makes games more along the lines of Dungeon Monster DX: The Fire! Time was, you could take your Dungeon Monster games and package them so your average Todds and Brandons would buy them. That’s been a challenge Japan has yet to surmount in this modern era. But why is this such a challenge if it wasn’t before?

Instant Connection

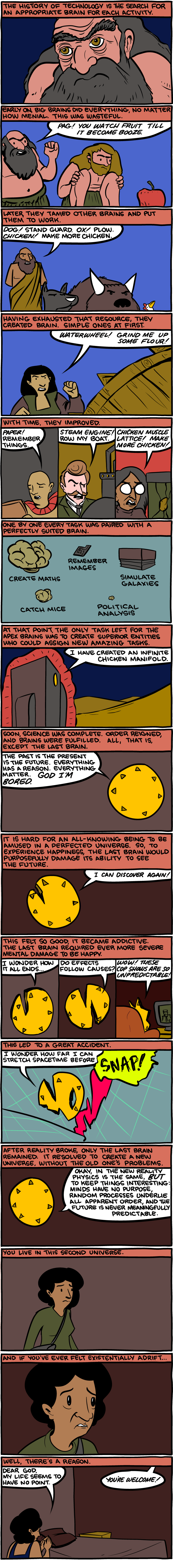

When we hear a story, our mind does its best to connect us to the story’s main character. We want to get to know that character so we can become the hero and experience the tale explicitly. In traditional storytelling, this is no easy task. It takes a witch’s brew of situation, exposition, and time to make a character connection with an audience. And few writers ever know what’s going to work in a given story.

Video games don’t have this problem. It’s a unique storytelling medium. The connection a game character has to the player is almost immediate. My go-to storytelling guru, Scott McCloud, best explains why, by summarizing philosophy first put forth by Marshall McLuhan:

When driving, for example, we experience much more than our five senses report. The whole car—not just the parts we can see, feel and hear—is very much on our minds at all times. The vehicle becomes an extension of our body. It absorbs our sense of identity. We become the car. If one car hits another, the driver of the vehicle being struck is much more likely to say: “Hey! He hit me!!” than “he hit my car!” or “his car hit my car,” for that matter.

So, in touching and controlling the car, your mind makes the car an extension of yourself. The same happens when playing a game. That touch of the controller and your control over the avatar gives your mind the same connection. The hero is a virtual extension of you. You become the hero as soon as you start the game.

This explains why games with subpar stories can still be great games. Your connection to the experience is immediate and doesn’t require a fantastic story to draw you in. If the game is enjoyable, you keep playing because you like your role as the hero. But what happens when you don’t like the hero you become?

Different Heroes For Different Hemispheres

Back to the Inifinity Ventures Summit (we were talking about that, right?). Some interesting statements were made by Sega/Sammy president, Hajime Satomi. Read below his hypothesis on why Japanese games fail to make an impact in the U.S. And Europe:

Europeans and North Americans like strong people, so the main character has to be a fully-grown, middle-aged man. On the other hand, in Asia, people like stories about middle or high school students growing up or becoming stronger. As you make games for more dedicated players, I think you have to be aware of those differences.

This makes sense when you consider characters from best-selling games in the U.S. from the past ten years: Kratos, Nathan Drake, Master Chief, Niko Bellic, Marcus Fenix, and that hooded guy from Assassin’s Creed. All severely grizzled, middle-aged combat types.

Compare that with some of Japan’s top character picks, plucked from a Famitsu poll of readers’ favorite characters: Link, Sora, Yuri Lowell, Sakura Shinguji, and Cloud Strife. All very ungrizzled and full of youthful optimism for the adventures of life (until they enter the job market).

There is some crossover, of course. Both east and west love Chris Redfield, Solid Snake, Link and Cloud. But there is something to Satomi’s ideas. There is clearly a difference in hero preference between hemispheres.

So if Japan once ruled the western gaming market, they must have created games with middle-aged heroes. Not necessarily.

Let’s Compare Some Box Art!

This is a simple exercise. I will present three games released both in Japan and the U.S. We will observe the in-game pixelated sprites that represent the main character(s) and the art on the boxes for the Japanese and U.S. releases of the game. Let’s begin.

DOWNTOWN NEKKETSU MONOGATARI vs. RIVER CITY RANSOM

The in-game character looks pretty cartoony. Could be any age.

Japanese Box Art:

The Japanese release of the game suggests the characters are young high school students.

US Box Art:

But the U.S. release suggests they are weird 36-year-old dudes! Despite that “River City High School” sign behind them, these two are clearly just there to pick up their kids from baseball practice.

ROCKMAN 2 vs. MEGA MAN 2

![]()

The age-neutral Mega Man sprite we know and love.

Japanese Box Art:

Japan gets some great art that actually looks a good deal like our robot friend on the screen.

U.S. Box Art:

America gets a welder with a broken foot and ray gun. He’s a weirdo, but he’s a grown-up combat weirdo!

DRAGON QUEST II vs. DRAGON WARRIOR II

Here’s the in-Game Characters – Japan & U.S.

These in-game characters could be impetuous teens or seasoned adventurers.

Japanese Box Art:

The art for Dragon Quest II features Akira Toriyama’s youthful depictions of the heroes, which have become a staple of the series.

U.S. Box Art:

The American release of Dragon Warrior II is, again, a band of fully-grown adults. These heroes promised each other in college that when they turned 40, they would reunite for a quest to Las Vegas.

Finding Ourselves

So what does this box art comparison mean, exactly? I’ll get to that in a second.

The heroes on our TV screens during the 8-bit and 16-bit eras were less defined and more iconic, and thus more easily interpreted. I touched on this in my article about Hello Kitty, so for a more detailed and Tom Hanks-oriented explanation of icons.

But there was another force at play, helping us interpret our pixel friends. That force is confirmation bias.

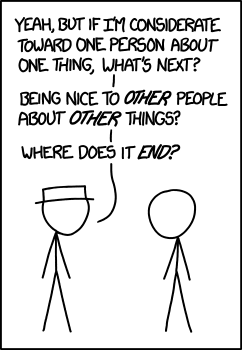

Confirmation bias is the psychological effect of your mind to favor information that coincides with your preconceptions. Traditionally, confirmation bias is used to describe how we gather information to make rational (or irrational) decisions. Recently, however, a young philosophy blogger named Sam McNerney introduced this idea:

If we are defining confirmation bias as a tendency to favor information that confirms our previously held beliefs, it strikes me as ironic to think that it is almost exclusively discussed as a hindrance to knowledge and better decision-making…With such a broad definition, I think it also explains our aesthetic judgments… Put differently, confirmation bias influences our aesthetic judgments just as it does any other judgment.

Since the pixelated hero images transmit so little information as to what they are, players needed the box art to confirm their bias of what they wanted to see, in this case, their bias of what they think, aesthetically, a hero should look like. Japanese gamers’ biases said, “this pixelated image is a youngling,” and the box art confirmed their bias. Western gamers’ biases said, “this pixelated image is muscular manbeast,” and their different box art confirmed their different bias.

Since video games, as we said earlier, offer an instant connection for the player, it is imperative that the player like that connection. Giving players the chance to connect to the heroes they wanted to be helped to ensure they would not put down the controller and, furthermore, keep buying games.

The Beginning Of The End

So that’s it. Everyone was happy, and all it took was paying two artists to do the same job. It’s easier to sell people what they expect than to challenge their perceptions. Unfortunately, this box art trick got harder to pull off as console gaming entered the world of polygons in 1995. Keeping the hero’s in-game appearance ambiguous got a little trickier.

Such was the case with The Legend of Zelda‘s transition from 2D to 3D. For the most part, early polygonal models could still be interpreted by both cultures as the heroes they wanted to be. And so it was with 1998’s The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time on Nintendo 64. EVERYONE loved this game. The main character, Link, started out as a kid but later grew into an adult. But what kind of adult? A grizzled one, probably.

How old is this adult Link? Fifteen or thirty-five?

When the first Zelda game for the 128-bit Gamecube was announced, Americans eagerly anticipated their powerful adult Link to appear in new, beautifully rendered 12 million polygons per second! It was at this point Nintendo thought it would be a good idea to have Link represented as a very cartoony boy child in The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. Americans went nuts. Angry nuts! Link had always been an elfin lad since the very beginning, according to the series’ story, but in pixel world and the American mind, he was nice and grizzled. For the first time, gamers were faced with a Link they could not interpret to their liking. Despite The Wind Waker being a gaming triumph, it sold a mere 3.07 million copies worldwide, compared to Ocarina of Time’s 7.6 million.

It was around this time, Japan’s control over the gaming industry began to wane. Of course, it was not solely due to the unambiguous heroes. The Xbox launched with incredible success in 2001, eating away at a large part of the North American market share previously held by Nintendo, Sega, and Sony. American video game companies, having learned from two decades of great Japanese games, started making games just as good or better. The spike in popularity that Japanese pop culture saw in 1999 was diminishing by the mid 2000’s, banishing anime from general acceptance back to the cavern of the nerds, which also meant the unmistakably Japanese video game heroes were banished as well (unless they were grizzled).

In our modern era, we have our two camps making games for themselves. American game companies churning out gritty power lunks and Japanese companies churning out sleek action teens. And we like it that way, apparently. Only a small fraction from each side is interested in games from the other.

The Sun Also Rises

2014. In a few months, the next Infinity Ventures Summit will be held in Sapporo and the Japanese gaming industry will gather once again to discuss the future, the past being a non-issue. The truth is, Japan will likely never again rule the video game world as it once did. The special circumstances of an evacuated market and technology that was easily localized is gone forever. Global competition and the advent of mobile/social gaming has changed the industry so nobody knows what to expect anymore. (BIRDS being angry at PIGS?! Nobody saw that one coming.)

But that’s okay. Industries change. When Georges Méliès and the Edison Trust dominated the film industry, it was only a matter of time before other artists from around the world said, “I want to do that, too!” Film expanded until people loved it so much that certain individuals began making films simply as artistic expression.

The Infinity Ventures Summit is a gathering of companies, so their primary concern should be how to sucker people out of money (using video games, hopefully). But games are made by artists, so I hope when these artists gather in May, they will talk, at least individually, about how to move video games forward as medium, how to push boundaries and make something people have never seen before. There will always be success in giving people what they expect. But there is a truer reward in creating something that changes peoples’ minds.

Bonus Wallpapers!

Sources:

- Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art by Scott McCloud

- Why doesn’t Japan like first-person shooters? Old characters and World War II, says Sega exec, by Casey Baseel

- Confirmation Bias and Art, by Samuel McNerney

- LVLs. Cultural Anxiety Features

- Famitsu’s Top 50 Video Game Characters

It's an impressive piece of technical work, and it will certainly be interesting for fans of the Office to see the incredible range of allusions embedded in the show—Sabia clipped out and identified over 1,300 from 9 seasons of the program. But it also makes an important point about copyright and culture, and is itself a perfect demonstration of how certain assumptions baked into our current law are out of line with reality.

It's an impressive piece of technical work, and it will certainly be interesting for fans of the Office to see the incredible range of allusions embedded in the show—Sabia clipped out and identified over 1,300 from 9 seasons of the program. But it also makes an important point about copyright and culture, and is itself a perfect demonstration of how certain assumptions baked into our current law are out of line with reality.

The Freedom of Information Act is not the only law the public can use to obtain records from the government. Most states have similar laws for accessing documents on the state and local levels. Here in California, EFF is using the California Public Records Act to learn what new technologies local law enforcement agencies are using and whether these technologies violate our rights.

The Freedom of Information Act is not the only law the public can use to obtain records from the government. Most states have similar laws for accessing documents on the state and local levels. Here in California, EFF is using the California Public Records Act to learn what new technologies local law enforcement agencies are using and whether these technologies violate our rights.

Iran Foreign Minister Javad Zarif with EU High Representative Catherine Ashton at the EU+3 and Iran talks, November 2013

Iran Foreign Minister Javad Zarif with EU High Representative Catherine Ashton at the EU+3 and Iran talks, November 2013