In 2017 I wrote a book about Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google called The Four. After working my ass off for 25 years, I became an overnight success: speaking gigs, appearances on cable news and talk shows, book and podcast deals. I spent a bunch of time with elected officials, and powerful people wanted to have lunch with me. People were fascinated — shocked, even — by this simple observation: Big Tech is powerful, maybe too powerful.

Much of the concern was a function of the ad-driven nature of platforms — algorithms that tapped into good/bad aspects of human nature to addict us. Most people knew how Facebook and Google made money, but not how they actually worked, how the ad revenue was fueled by the collection of data and the harvesting of attention. In fact, the phrase “Big Tech” was barely known back then. (Check the Wikipedia entry for Big Tech and see which NYU professor is credited with defining the category.) I just read the last sentence and realized I still crave other people’s affirmation. #Pathetic.

Anyway, things are different today. We know we’re being tracked, and we understand how digital platforms make money. We also know they are lucrative, as in, among the fastest growing, most profitable businesses in history. Since A Beautiful Mind won Best Picture in 2002, Google has grown its revenue 625-fold. Digital ads transformed the company from a garage project into a multinational corporation, and turned Meta from a college-campus website into the largest media business in the world. If you had to bet everything, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to go with whoever controls our attention. Meta or Google? Safe bets. Snap? Riskier, but the moppets love it. It’s fun to flirt with other sectors and firms, but these companies are the smart, safe bets.

Until now.

Sea Change

This is proving to be a historically bad year for tech. Few saw it coming. If you bought Facebook stock in 2015, you’ve lost money. If you purchased shares of General Motors, IBM, or Chevron, you’ve made more money than Meta shareholders. Seven years of gains, erased in 10 months. Meta’s meltdown is shocking, but not singular. Google is down 40% this year, Amazon 45%, and Snap 80%. These losses are unprecedented in the Big Tech era.

As with bankruptcy, the sell-off happened gradually, then suddenly. Last week was a turning point. Amazon, Google, Meta, and Snap all missed big on earnings. The common theme? Ads. Or lack thereof. We knew the Mad Men era had come to an end; we weren’t expecting the end of Ad Men. But let’s be honest, advertising sucks. Cable ads provide a glimpse into what it’s like to have restless leg syndrome, and digital ads, while more relevant, are carbon — the noxious byproduct of converting attention into shareholder value via algorithms that bring out the worst in the species. I’ll say it again, advertising sucks.

In a surprising turn of events, ads have become Big Tech’s Achilles’ heel. Google’s ad revenue grew just 3% this quarter, down from 43% growth a year ago. For the first time, YouTube ad revenue declined. Snap registered its slowest ad revenue growth ever. Meta’s ad sales, which make up more than 98% of the business, were a trainwreck. Meanwhile (and yes, this brings me joy) the company continues to incinerate $2 billion a month feeding Mark’s fever dream that he is a god of new worlds. BTW, it appears people are more likely to worship Tom: MySpace has more traffic than Meta’s Horizon Worlds.

Macro

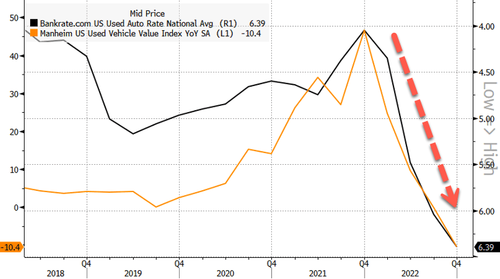

What is/are the meteor(s) that have struck the Gengis & Khan of ads? Meta says the problem is “the uncertain and volatile macroeconomic landscape.” Google blames “the challenging macroclimate.” Snap, “macro headwinds.” Macro, as in, rising inflation, interest rates, and supply chain issues all conspiring to depress advertising demand. And it makes sense, because if people stop spending money on stuff, then the businesses that make that stuff have less money to spend on advertising.

But here’s where it gets scary for these companies’ shareholders: The “macro” culprit is a ghost, as people haven’t stopped spending. U.S. consumer spending beat expectations in September, rising 0.6% for the second month in a row. Meanwhile, the U.S. economy is doing, well, fine — U.S. GDP grew 2.6% last quarter. Of course, there’s still a lot of uncertainty. Growth has slowed, and we’re by no means in the clear. But the weakness we’re seeing in the macroeconomy is a drizzle compared to the Category 5 shitstorm we’re seeing in digital advertising.

The state of the economy is a distraction here. Something else is killing ads, and tech companies are reluctant to acknowledge it because, unlike the economy, it’s not cyclical but structural. Hint:

Elephant No. 1

The elephants in the room are Apple and TikTok. Apple is the larger of the two, figuratively and literally. Last week, the Cupertino giant cemented its position as the most enduring tech company in history: Facing the same macro headwinds as Google and Meta, Apple beat earnings expectations on both the top and bottom lines. At $2.4 trillion in market cap, the company is roughly 10 times more valuable than Meta. Three years ago, it was twice as valuable. It’s getting easier to understand why the Zuck wants out of this universe.

Executioner

Apple may be the last thing an ad-driven platform sees before everything goes black. A year ago, Apple’s iOS upgrade forced apps, including Facebook and Instagram, to ask users for permission to track their data. Meta relies on that data to serve personalized ads that garner greater clicks and sales. So if users opt out, the ads become less effective, and Meta, dramatically less valuable.

But few predicted the change would hurt Meta this much. Turns out when Apple’s privacy prompt pops up, only 16% of users agree to being tracked. And if data is the new oil, ad platforms are losing 84% of their Brent Crude. Apple has gone Putin on Meta’s Germany by cutting supply — though this decision was positioned more virtuously, in the name of privacy, vs. war.

Without data, the digital ad ecosystem doesn’t work. I saw this play out in real time. Here at Prof G Media, we collect data — specifically, whether or not you opened this email. It’s not powerful data, but it’s data. It helps us understand what resonates. However, several months ago our open rate fell off a cliff. Why? Apple’s privacy change: Every iPhone reader started showing up as a no-open. Overnight, our data had become useless.

This newsletter isn’t monetized, so the data blackbox isn’t a game changer. But for most online businesses, it’s dire. Small e-commerce companies across the country have seen customer acquisition costs skyrocket … by 10 times. Why? The ads are no longer shown to the right people at the right time. As a result, small businesses have had to shift spend. Since the iOS upgrade, almost half of e-commerce store owners have decreased their Facebook ad spending by 25% or more. This year, the average price of ads on Meta declined 20%. One year ago, before the privacy change, prices had risen 20%. Tim’s revenge turned Meta, overnight, from a spry, twentysomething growth stock into a Golden Girl, mature and complaining.

Elephant No. 2

In advertising, the pie stays the same. The industry has consistently accounted for roughly 1.3% of U.S. GDP. Which means a couple things: 1) There’s always demand, and 2) it’s a zero-sum game. As with foreign exchange, every increase is met with a commensurate decrease somewhere else.

So if the money isn’t going to Facebook, where is it going? The phantom menace here is TikTok. Last quarter (the same quarter Google, Meta, and Snap got crushed), TikTok was the highest-grossing app for the fourth consecutive quarter — meanwhile, the rest of the app market declined. It was also the most downloaded app on the App Store, and more than a quarter of Americans under 30 now get their news from it. TikTok’s global ad revenue will triple this year, to $12 billion, which would best the revenue of Snap and Twitter combined. That number doesn’t include Douyin, TikTok’s China-based counterpart. ByteDance, the parent company that houses these assets, was recently valued at $300 billion. That’s roughly equal to Meta, Snap, and Twitter (at Elon’s inflated price) combined.

TikTok’s growing influence is well documented. We’ve discussed it many times before. Less discussed is the extent to which Xi and Cook have formed an unspoken alliance to repel the advance of Meta. The company is in full-blown retreat. After Facebook and Instagram ads became less effective, ad buyers overwhelmingly turned to TikTok. Standard practice, according to one ad firm, was to move 10% to 15% of ad spend from Facebook to TikTok. The data is opaque (part and parcel of ByteDance being China-owned), but the trend is clear: TikTok is becoming the premier ad platform.

You’d think TikTok would be just as susceptible to Apple’s privacy change as Facebook. After all, TikTok’s ads are fueled by an algorithm, which is fed with your data. But research suggests TikTok is more insulated against Apple’s privacy change than others. According to cybersecurity experts, TikTok can circumvent Apple’s code audits and track activity without the user’s knowledge. Exactly how this works is (again) not so clear, and that’s the point — as one expert pointed out, “ByteDance has gone to monumental lengths to conceal the inner workings of the app.” What could go wrong?

Rangers

I’m on a plane as I write this, taking my sons to see the Glasgow Rangers play St. Johnstone in Perth, Scotland. We are football mad, and I want my sons to see my dad’s favorite team in a 10,000-seat stadium. I’m trying to re-create a memory my dad used to tell me about, when he and his father went to this same game — the Rangers were his team. He’d get emotional talking about that day, one of his few memories of doing something, alone, with his father.

About 20 years ago, I stopped dwelling on my dad’s shortcomings, put the bullshit aside, and decided to be the son I’d like to be … full stop. The catalyst for this was his sister telling me he’d been physically abused by his father. He had never mentioned this. The idea that the person you should trust most would beat you, and the damage that must do to a young soul, is unthinkable. When I told my dad about our trip, he didn’t remember who the Rangers were. He’s 92 and struggling. As his attention and memories are disappearing, I’m riddled with questions that will likely never be answered: What planes did he repair while serving in the Royal Navy? My mom, his second wife, told me his first wife tried to kill herself after he told her he was leaving her — is this true? Another difficult subject I never had the confidence to broach. All of a sudden, a ton of questions.

This weekend, I will take a bunch of videos of us rooting for the Rangers and send them to my father. I’ll also send them to my sons with a voiceover. I will tell them what I know of their grandfather’s affinity for the Rangers. I’ll also tell them that I have no interest in football, but love it because they love it, and it makes me feel closer to them. And that when they were born, for the first time, I knew I had purpose. That all “this” meant something.

Life is so rich,

P.S. I’ll go deeper on Big Tech and the strategies that do work for it in the Business Strategy Sprint, happening Dec 5-9. Join me. Sign up here.

The post Elephants in the Room appeared first on No Mercy / No Malice.

Some have raised questions and concerns about the “gig” economy and the rise of these new independent and autonomous work types. Detractors frequently highlight that these work types lack some of the structured benefits that are frequently attached to traditional full time job offerings. However, what they fail to consider is that there is one critical and fundamental feature of the “gig” economy that is completely absent from traditional job types. That feature — worker autonomy of both time and place — simply does not exist in other industries. One cannot show up for work at Starbucks on a Monday and then decide not to work at all on Tuesday, and for only 2 hours on Wednesday. Oh yeah, and then on Thursday let’s just “play it by ear.” One cannot get a job at Walmart or McDonalds or ironically even as a taxi cab driver without agreeing to some sort of shift or schedule. It is unheard of for an employee to say “I want to work 3 hours this week, 45 the next, and then take 2 weeks off.” This autonomy and freedom of the “gig” work type, which is highly valued by millions and millions of people, would be impossible to implement for the overwhelming majority of companies.

Some have raised questions and concerns about the “gig” economy and the rise of these new independent and autonomous work types. Detractors frequently highlight that these work types lack some of the structured benefits that are frequently attached to traditional full time job offerings. However, what they fail to consider is that there is one critical and fundamental feature of the “gig” economy that is completely absent from traditional job types. That feature — worker autonomy of both time and place — simply does not exist in other industries. One cannot show up for work at Starbucks on a Monday and then decide not to work at all on Tuesday, and for only 2 hours on Wednesday. Oh yeah, and then on Thursday let’s just “play it by ear.” One cannot get a job at Walmart or McDonalds or ironically even as a taxi cab driver without agreeing to some sort of shift or schedule. It is unheard of for an employee to say “I want to work 3 hours this week, 45 the next, and then take 2 weeks off.” This autonomy and freedom of the “gig” work type, which is highly valued by millions and millions of people, would be impossible to implement for the overwhelming majority of companies. In November of 2014, the Morgan Stanley sell-side research team that focuses on the auto industry, headed by Adam Jonas, made a trip to Detroit to visit the big three automakers. In their own words, “the highlight of the trip, however, was three Uber trips we took between meetings.” They chronicled these three trips in a report they published titled,

In November of 2014, the Morgan Stanley sell-side research team that focuses on the auto industry, headed by Adam Jonas, made a trip to Detroit to visit the big three automakers. In their own words, “the highlight of the trip, however, was three Uber trips we took between meetings.” They chronicled these three trips in a report they published titled,

In October of 2016, McKinsey and Company (working with Uber) published a detailed research report titled,

In October of 2016, McKinsey and Company (working with Uber) published a detailed research report titled,  Another reason Uber is such a great supplemental work type is that peaks in usage elegantly overlap with time windows that are convenient for traditional 9-5pm, Monday-Friday full-time workers. Friday and Saturday nights are simultaneously the consistent weekly peaks of (a) demand on the Uber system, and (b) spare time that is available for people with standard full-time jobs that want to pick up some incremental income (the chart to the right highlights this). The same thing happens with holidays and festivals. The need for rides (and therefore drivers) at music festivals or seasonal events or in a vacation town like Tahoe are bursty. That said, these same holiday weekends are when people searching for supplemental income are free from the primary occupation and can make the voluntary decision to earn more money. I have met drivers in Tahoe that came to town with their family (on vacation) and are earning while others are hiking or skiing. The matching of this excess supply with excess demand is both elegant and fortunate.

Another reason Uber is such a great supplemental work type is that peaks in usage elegantly overlap with time windows that are convenient for traditional 9-5pm, Monday-Friday full-time workers. Friday and Saturday nights are simultaneously the consistent weekly peaks of (a) demand on the Uber system, and (b) spare time that is available for people with standard full-time jobs that want to pick up some incremental income (the chart to the right highlights this). The same thing happens with holidays and festivals. The need for rides (and therefore drivers) at music festivals or seasonal events or in a vacation town like Tahoe are bursty. That said, these same holiday weekends are when people searching for supplemental income are free from the primary occupation and can make the voluntary decision to earn more money. I have met drivers in Tahoe that came to town with their family (on vacation) and are earning while others are hiking or skiing. The matching of this excess supply with excess demand is both elegant and fortunate. There is another incredible driver-partner benefit of the Uber system that is radically different from traditional work types.

There is another incredible driver-partner benefit of the Uber system that is radically different from traditional work types.  In just a few short years, over 3 million driver-partners have joined the Uber platform. To put that in perspective, Walmart has grown to 2.3 million employees over 55 years. I think it’s safe to say that over the past five years, no industry has created more new jobs and new income opportunities than ride-sharing. And keep in mind that approximately three-fourths of the industry revenue goes straight to the labor provider — which is higher than almost any other industry on the planet. As a result, in just a few short years, global ride-sharing driver-entrepreneurs have taken in approximately $75+ billion dollars (with industry lifetime revenues north of $100 billion dollars). And keep in mind that ride-sharing

In just a few short years, over 3 million driver-partners have joined the Uber platform. To put that in perspective, Walmart has grown to 2.3 million employees over 55 years. I think it’s safe to say that over the past five years, no industry has created more new jobs and new income opportunities than ride-sharing. And keep in mind that approximately three-fourths of the industry revenue goes straight to the labor provider — which is higher than almost any other industry on the planet. As a result, in just a few short years, global ride-sharing driver-entrepreneurs have taken in approximately $75+ billion dollars (with industry lifetime revenues north of $100 billion dollars). And keep in mind that ride-sharing  In all the discussion about why independent work is different than a traditional full time occupation, all of the focus has been on the features and benefits that are absent relative to the historic and perhaps idyllic notion of “work type.” What is missing from the conversation is why this job type is so special and unique to so many millions of people. There is simply no way for the vast majority of employers in the world to offer a completely independent and autonomous work-schedule. They are unlikely to enable “instant payment” either. Yet these are the EXACT same features that show up over and over again in the research as to why people chose independent work in the first place. Independent work is undisputedly “different” from a traditional job type — which is exactly why it is so valuable to so many people.

In all the discussion about why independent work is different than a traditional full time occupation, all of the focus has been on the features and benefits that are absent relative to the historic and perhaps idyllic notion of “work type.” What is missing from the conversation is why this job type is so special and unique to so many millions of people. There is simply no way for the vast majority of employers in the world to offer a completely independent and autonomous work-schedule. They are unlikely to enable “instant payment” either. Yet these are the EXACT same features that show up over and over again in the research as to why people chose independent work in the first place. Independent work is undisputedly “different” from a traditional job type — which is exactly why it is so valuable to so many people.