Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

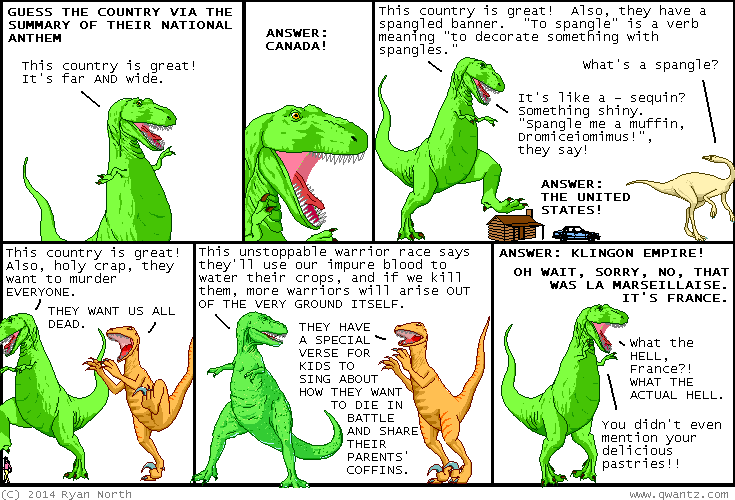

#1044; In which Edwin is made Aware

http://powerpopcriminals.blogspot.com/2014/07/xtc-gribouillage-1992-rare-cdep-given.html

Some countries are born great, some achieve greatness, but all have greatness thrust into their national anthem

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | July 8th, 2014 | next | |

|

July 8th, 2014: La Marseillaise, ladies and gentlemen! I actually don't know what the anthem of the Klingon Empire is :( :( D: – Ryan | |||

A Presumptious Dilettante's Five Belated Eggs

This isn't just a moral imperative. Sure, the Left must stand with the oppressed. Always. By definition. Otherwise why bother being on the Left? Otherwise, what does 'The Left' mean? But it's also a tactical imperative. The system must be attacked at its weakest points. The righteous and rightful rage felt by many on the axis of Trans oppression is absolutely one of the system's weakest points. It hits people where they live: in their bodies. Bodies are oppressed, disciplined, punished, curtailed, invaded, wounded and even dissected by capitalism... and it behoves the Left to realise that this happens in arenas outside the sites of direct capitalist production. This is one of those things that everyone formally 'gets' and then puts to one side. That's not good enough. Capitalist oppression is total, hegemonic, far-reaching and omnipresent. It is intimately and demonstrably bound up with oppression along lines of personal identity, bodily autonomy, bodily identity, sexual identity, gender, sexuality, and race. This is why intersectionality is a crucial concept that's only going to get more crucial. The task will be to relate all these issues to class. Not so that they can be subsumed, assimilated and/or digested, but so the analysis wielded by the Left can be enlarged, educated, made stronger and more inclusive. That is an end in itself - if we know what our ultimate goal really is.

The good news is that class is as intimately bound up with these things as the Left thinks it is. The bad news is that we have to stress the importance of class without playing 'issue trumps' (i.e. our preferred axis of oppression is more crucial or 'primary' or 'causal' than yours... and, by the way, how dare you stress the issues that hit you where you live before the issues that we think of as theoretically more important???).

But there is more good news. We can stress how capitalism, and thus class exploitation along lines of work and wage exploitation (which is basically just another way of saying 'capitalism'), generates and exacerbates such oppression... for the simple reason that it bloody does; it's the currently regnant form of class society, and we can adduce powerful facts to show how the structure of class society generates sexism, female oppression, gender essentialism, the reduction of people to categories, the reification of socially constructed categories into hegemonic 'facts of life', etc.

That's why this is so good. There isn't anything in there that constitutes new and startling revelation, but it's a great little summary/primer/starting-point, from the perspective of a totally 'on-side' Marxism. I found it so anyway - speaking as someone who personally embraces the elderly Goya's maxim "I'm still learning".

One (related) crucial issue to remember... and here I'd proffer the great work of Silvia Federici... is that the oppression of women is not an optional extra with capitalism, nor is it a by-product of capitalism. It is certainly generated and exacerbated by capitalism (part of the argument the Left needs to make) but is also a precondition of capitalism, intimately bound up with the creation of capitalism, and partly capitalism's parent.

The oppression of women existed before capitalism, because capitalism is a form of class society built on top of previous forms of class society (in Europe, feudalism)... just as the capitalist states are forms adapted from pre-capitalist states. And the rise of capitalism in Europe was absolutely and fundamentally bound up with the further domestication, persecution and economic subjugation of women (see Federici, among others). There really is very little wiggle room here to say that one caused the other. They are two sides of the same coin. And 'causality' or 'primary position' loses its meaning in a truly dialectical (i.e. a truly Marxist) analysis. Besides, its an academic question.

LGBTQIA+ oppression is, once again, related. (BTW: please forgive my using the long acronym as shorthand if you don't like the 'lumping together' effect, or if you're on the other side and worry that trying to be that inclusive accidentally implies that anything not covered is, by definition, not included... and also, please don't construe my raising of LGBTQIA+ oppression as an afterthought.) LGBTQIA+ oppression is intimately connected with the issue of women's oppression, and not in the sense of being a 'product' or 'by-product' or 'side effect' of it, but rather as another aspect of the suffocating enforcement and reification of gender that class society entails, relies upon, and by which it is partly produced.

Can geekiness be decoupled from whiteness?

As a fledgling nerd in my teens and early twenties, grammar pedantry was an important part of geek identity for me. At the time, I thought that being a geek had a lot to do with knowing facts and rules, and with making sure that other people knew you knew those facts and rules. I thought that people wouldn’t be able to communicate with each other clearly without rigid adherence to grammatical rules, a thought that may have been influenced by the predominance of text-based, online communication in my social life at the time.

The image shames people for where they place commas and suggests sarcastically that a punctuation error could result in misunderstanding of a suggestion to have a meal as a suggestion to practice cannibalism.

If Facebook had existed at the time, I would have been sharing this image, and others like it, with the best of them. I was sure that correct use of punctuation and adherence to the grammatical rules of standard American English was an essential step along the way to achieving truth, justice, and the American Way. Though I wasn’t sure exactly how. It definitely seemed a lot easier to teach people how to use commas correctly than to teach them how to take another’s point of view (something I wasn’t very good at myself at the time), and like the drunk looking for their keys underneath the lamppost because that’s where it’s easier to see, I ran with it.

Nerds, Rules, and Race

A few years ago, Graydon Hoare mentioned Mary Bucholtz’s article “The Whiteness of Nerds” (PDF link) to me. As a recovering grad student, I don’t read a lot of scholarly articles anymore, but this one has stayed with me. Perhaps that’s because the first time I read it, felt embarrassed. I felt that I had been read. By this point, I suppose I had let go of some of my attachment to grammar pedantry, but I still felt that it was just a bit of harmless fun. I realized that without being consciously aware of it, I had been using devotion to formal rules as a way to perform my whiteness — something that I would certainly have denied I was doing had someone accused me of such.

Bucholtz argues, in short, that geek culture (among American youths) is a subculture defined, essentially, by being whiter than white:

“This identity, the nerd, is racially marked precisely because individuals refuse to engage in cultural practices that originate across racialized lines and instead construct their identities by cleaving closely to the symbolic resources of an extreme whiteness, especially the resources of language.”

Bucholtz is not saying that there are no nerds of color — just that nerd culture, among the teenagers she studied, was defined by hyper-devotion to a certain set of white cultural norms (which some youths of color are perfectly happy to adopt, just as some white youths perform an identification with hip-hop culture).

If we accept her analysis of nerd culture, though, it’s clear that it excludes some people more than others. Adopting hyper-whiteness is an easier sell for people who are already white than for people who are potentially shrugging off their family of origin’s culture in order to do so. If it’s assumed that a young person has to perform the cultural markers of nerd culture in order to be accepted as someone who belongs in a science class or in a hackerspace, then it’s harder for youths of color to feel that they belong in those spaces than it is for white youths. That’s true even though obsessing about grammar has little to do with, say, building robots.

In my own youth, I would have said that I liked nitpicking about grammar because it was fun, probably, and because I wanted to communicate “correctly” (perhaps the word I would have used then) so that I could be understood. But was I harping over it for the intrinsic pleasure of it, or because it was a way for me to feel better than other people?

I think people who have been bullied and abused tend to use rules in the hopes that rules will save them. It’s true that many kids who are academically gifted and/or interested in science, math and engineering experience bullying and even abuse, even those who are otherwise (racially, gender-wise, and economically) privileged. It’s also true that some of the same people grow up to abuse their power over others in major ways, as most of the previous posts on this blog show. As a child, I thought that someday, someone was going to show up and stop my mother from abusing me and that that would be made possible by the fact that it was against the rules to hit children. I think that’s part of how I got so interested in formal systems of rules like grammar — eventually leading me to pursue programming language theory as a field of study, which is about using formal systems of rules to make computers do things. I suspect many nerds had a similar experience to mine.

But it’s easier to like formal systems of rules when those rules usually protect you. If you live in a country where the laws were made by people like you, and are usually enforced in ways that protect you, it’s easier to be enamored of technical adherence to the law. And, by analogy, to prescriptive sets of rules like “standard English” grammar. It’s also easier to feel affection for systems of rules when people like yourself usually get a say in constructing them.

Not all nerds are abuse survivors, so perhaps other nerds (as adults) value rule-following because they believe that their aptitude for compliance to formal systems of rules is the key to their economic success. From there, it’s easy to jump to victim-blaming: the line of thought that goes, “If other people would just learn and follow the rules, they would be successful too.”

“Mrs. Smith is a wonderful linguist. Give her a few hours with a grammar and she’ll know everything except the pronunciation.” — Graham Greene, The Comedians

In Graham Greene’s novel The Comedians, set in Haiti in the 1950s, Mrs. Smith — an American who is in the country to proselytize for vegetarianism (not realizing that in the country she’s visiting, nobody can afford to eat meat) — believes that all she needs to do to speak the language of the natives, wherever she’s going, is to memorize the language’s grammatical rules. Not only does she not (apparently) realize the difference between Haitian Creole and Parisian French, she doesn’t seem to know (or doesn’t care) about idioms, slang, or culture. If she really is a wonderful linguist, perhaps she has a native ability to pick up on connotations, which she’s discounting due to her belief that adherence to rules is what makes her successful.

In general, it’s possible that some grammar pedantry is motivated by a sincere belief that if others just learned how to speak and write standard English, they’d be able to pull themselves up by the proverbial bootstraps. But success doesn’t automatically grant insight into the reasons for your success. Maybe understanding rules is secondary to a more holistic sort of talent. Maybe you’re ignoring white privilege, class privilege, and other unearned advantages as reasons for your success, and others won’t enjoy the same outcome just by learning to be good at grammar.

Maybe it’s especially tempting for programmers to play the prescriptivist-grammar game. By nature, programming languages are prescriptive: for programs to make sense at all, a language has to have a formal grammar, a formal mathematical description of what strings of characters are acceptable programs. If there was a formal grammar for English, it would say, for example, that “The cat sat on the mat.” is a valid sentence, and “Mat cat on the sat.” is not. But there isn’t one; English is defined by what its speakers find acceptable, just as every other human language is. Different speakers may disagree on what sentences are acceptable, so linguists can outline many different dialects of English — all of which are mutually understandable, but which have different grammatical rules. There is no correct dialect of English, any more than any given breed of dog is the correct dog.

Programming consists largely of making details explicit — because you’re talking to a not-very-bright computer — that most other humans would be able to fill in from context. Context is why most of the grammar memes that people share are very shallow: no English speaker would actually sincerely confuse “Let’s eat Grandma!” with “Let’s eat, Grandma”, because of contextual knowledge: mostly the contextual knowledge that humans don’t treat each other as food and so the first sentence is very unlikely to be intended, but also the contextual knowledge that we’re talking to Grandma and have been talking about preparing dinner (or, I suppose, the knowledge that we have survived a plane crash and are stranded with no other food sources). If punctuation really was a life-and-death matter any appreciable portion of the time, the human race would be in deep trouble — on the whole, we’re much better at spoken language, and written language is a relatively recent and rare development.

But I think programmers have a good reason to value breaking rules, because that’s what programmers do whenever they are being truly creative or innovative (sometimes known as “disruption”). Hacking — both the kind sometimes known as “cracking” and the legal kind — are about breaking rules. In spoken language, grammatical rules are often (if not always) developed ex-post-facto. It’s probably more fun to study how people actually use language and discover how it always has internal structure than it is to harp on compliance with one particular set of rules for one particular dialect.

Bucholtz argues that nerds are considered “uncool” by virtue of being too white, surprisingly, since white people are the dominant cultural group in the region she was studying. She made that observation in 2001, though. Now, in 2014, “nerd” has come to mean “rich and high status” (at least if you’re male), much more than it means “unpopular and ignored”. We hear people talk about the revenge of the nerds, but are we really talking about the revenge of the hyper-white? Nerds often see themselves as rebelling against an oppressive mainstream culture; is it contradictory to resist oppression by defining oneself as “other” to the oppressor culture… by outdoing the oppressor at their own game?

Bucholtz addresses this question by arguing that while “cool” white youths walk a delicate balance between actng “too black” and “too white”, “nerdy” white youths resolve this tension by squarely aiming for “too white”. I don’t think she would say that the “cool” white kids are anti-racist, just that in defining themselves in opposition to the cool kids’ appropriation of Black American culture, nerds run the risk of behaving so as to devalue and stigmatize the culture being appropriated, intentionally or not.

Moreover, we know that cultural appropriation isn’t a respectful act; are the “hyper-white nerds” actually the anti-racist ones because they refrain from appropriating African-American culture? And does it matter whether we’re talking about youth culture (in which intellectualism can often go unappreciated) or adult culture (where intellectualism pays well)? I’d welcome any thoughts on these questions.

Unbundling Geekiness

What am I really doing if I click “Share” on that “Let’s eat Grandma!” image? I’m marking myself as discerning and educated, and I don’t even have to spell out to anyone that by doing those things, I’m shoring up my whiteness — the culture already did the work for me of convincing everyone that if you’re formally educated, you must be white; that if you aren’t, you must be poor; and then if you’re a person of color and formally educated, you must want to be white. I’m also marking myself as someone who has enough spare time and emotional resources to care a lot about something that has no bearing on my survival.

Incidentally, I’m also marking myself as someone whose neurology does not make it unusually difficult to process written language. There are similar memes I can share that would also mark me as someone who is not visually impaired and thus does not use a screen reader that would make it impossible for me to spell-check text for correct use of homophones. An example of the latter would be a meme that makes fun of someone who writes “fare” instead of “fair”, when the only way to avoid making such a typographical error is to have the ability to see the screen. In “Why Grammar Snobbery Has No Place in the Movement”, Melissa A. Fabello explores these points and more as she argues that social justice advocates should reject grammar snobbery. I agree, and also think that geeks — regardless of whether they also identify as being in “the movement” — should do the same, as it’s ultimately counterproductive for us too.

Geek identity doesn’t have to mean pedantry, about grammar or even about more substantive matters. The Hacker School Rules call out a more general phenomenon: the “well-actually”. The rules define a “well-actually” as a correction motivated by “grandstanding, not truth-seeking”. Grammar pedantry is almost always in the former category: it would be truth-seeking if it was about asking what unclear language means, but it’s usually targeted at language whose meaning is quite clear. I think that what the Hacker School document calls “grandstanding” is often about power dynamics and about who is favored and disfavored under systems of rigid rules. But rules are to serve values, not the other way around; I think geekiness has the potential to be anti-racist if we use our systems of rules in the service of values like love and justice, rather than letting ourselves be used by those systems.

Thanks to Chung-Chieh Shan and Naomi Ceder, as well as Geek Feminism bloggers Mary and Shiny for their comments on drafts.

Day 4932: You Can Prove Anything With Statistics Part Deux

This time it’s Tom Clarke writing in the Gruaniad to assert:

“How the Tories chose to hit the poor”

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/02/tories-poor-george-osborne-inequality-conservatives

(and just look at all those buzzwords in that URL!)

“George Osborne claims to have cut inequality,” adds the sub-editor. “But look behind the figures and it's clear the Conservatives can't take any credit.”

To summarize: the existing data points do not agree with his thesis so he says that they don't count and makes up what next year's figures will say instead.

It seems Iain Drunken Swerve isn’t the only one for whom denial is a preferred tactic.

The implications of the piece are that the CHOICES of the Coalition are bad ones, and therefore that any beneficial outcome is accidental. To come to that conclusion it is necessary to downplay, ignore or indeed run away and hide from the contribution of the Liberal Democrats to Coalition policy.

Inequality, measured by the Office for National Statistics figures for 2011/12, FELL in the UK under the Coalition, and the new 2012/13 figures show that fall has not reversed.

As Lib Dem Voice reports, the Institute for Fiscal Studies have commented that inequality is now lower than since before Tony Blair brought Labour back into government in 1997.

This is a fact.

A startling one but indisputably a fact. Startling not just because this is the first fall in inequality for nearly three decades, but also because it is unique among Western nations.

Is this a beneficial outcome?

What has happened has happened in the worst way. I – and I think most Liberals – would prefer to reduce inequality by raising everyone up, not grinding the richest down. Making the rich pay, that’s Labour’s way. In this recession, everyone has had to take a hit, including hitting some of the least well off, but proportionately the better off you were the more you’ve been asked to pay – from each according to their means, as it were. And it must gall Labour and the left that this Coalition has been more socialist than the socialists ever were.

But if, as Labour do, you subscribe to the “Spirit Level” thesis that more equal societies are happier, healthier and better then you would have to say this is a beneficial outcome. Even if you don’t subscribe, you would have to accept that the cost of the Crash had to be borne by someone, and these figures show that the better-off have shouldered their share of the burden. Those better able to pay have paid and as a result there has been a slight rebalancing of income after tax and benefits.

So is this just by accident or does it down to the choices we have made in government?

It is not difficult to see how it’s happened. Salaries were frozen or even reduced, whereas, at the insistence of the Liberal Democrats, benefits continued to be increased*, and with a triple lock pensions – more than half the Social Security budget – were and still are increased by even more.

(*Full disclosure: for the period covered by these figures, benefits were increased in line with inflation. For 2013/14 benefits were still increased, but we could not stop George Osborn capping many increases, but not pensions, at 1% – a cut in real spending power as it is below the rate of inflation. Because pensions increase by more than inflation, the impact of this is uncertain, but it does, of course, form the basis of Mr Clarke’s speculation that inequality will rise again in next year’s official figures.)

Add to that the effect of the flagship Liberal Democrat tax policy of raising the personal allowance, a tax cut directly aimed at the less well-off earners.

And the Liberal Democrats also required, in the price for Coalition, that Capital Gains Tax – a tax largely paid by the well-off – be increased from Labour’s inequality-creating low level of 18% to a more reasonable 28%.

Furthermore, the Lib Dems would not let Master Gideon reduce the top rate of tax from 50% to the 40% rate that it was under Labour.

Remember when Labour raised the top rate to 50p… for a MONTH. The Coalition because of the Liberal Democrats has a rate of 45% that is still higher than under any budget presented by Gordon Brown.

Remember when Labour DOUBLED the tax paid by those in the lowest band, and how Mr Balls still wants to reintroduce the 10p starting rate? The Coalition because of the Liberal Democrats gave those people a ZERO starting rate and took them out of paying income tax altogether!

You can see the theme here: Labour under Mr Blair and Mr Brown – who, if you recall, were in the words of Mr Peter “Prince of Darkness” Mandelson: “intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich” – saw inequality rise like a rocket. The Coalition, because of Liberal Democrats’ fair tax policies, has seen a remarkable fall.

For that fall in inequality to come about because “the Tories chose to hit the poor” IS. NOT. POSSIBLE.

Remember Labour’s COMPLICITY in the Great Crash of the Twenty-Nothings. It wasn’t ALL down to a few “rogue bankers”. I’ve written before of how Labour’s “borrow and spend” economic policy buoyed the bubble, how their “let the good times roll (on tick)” philosophy cheered on many millions of small borrowers to risk more than they could afford on the (fictitious) promise of a never-ending supply of cheap money lent from China – how often did Gordon Brown say “no more boom and bust”? What did he think he was encouraging people to do?

Remember how Labour were taking bungs and favours from everyone from Bernie Eccleston to Rupert Murdoch. They were deeply entwined with the really filthy rich.

Remember the facts of what Labour really DID, not the fairy story of good times that they want you to believe in.

Labour, even when they nationalised a bank or two, were only ever socialist by accident; we have achieved this by design.

In this crash (which, whatever the causes, you have to admit happened on Labour’s watch) everyone has done worse. But Liberal Democrat choices have made good on the Chancellor’s promises of being “all in this together”.

And that’s important to us because we CARE about a Fairer Society as well as a Stronger Economy.

The impression from his article is that Mr Clarke appears not to care that Labour never really cared at all.

"…so when the truth finally outs, what will be the response?"

Practically an admission there that he doesn't know that either. So he’s just making that answer up too. Not necessarily an unreasonable prognostication – Mr Drunken Swerve has form – but still not in fact fact.

The 2013/14 data – when it comes out next year – may (or may not!) undermine the Chancellor's current statement, but at least Mater Gideon is basing his words on the facts as they are known now. Mr Clarke and the Graun are not.

And the confirmation bias of 450 below the line CiFers nodding and saying “he’s right you know” does not count as supporting evidence.

Mr Clarke touches their G (for Grauniad) spot again by referring to the 2008 crash as “Lehman Brothers' implosion” pinning the blame on the bank and definitely not the profligacy of any governments that might have supposedly had oversight of the economy at the time.

And again we have the lazy accusation against the Coalition of “a government that has lurched to the right”.

Then there is this:

"This week's data only takes us up to this point, the financial year that began in April 2012"

This is such a weirdly constructed sentence that I have to wonder if it's deliberate. If you are talking about the point that the data takes us to, then surely it only makes sense to talk about the *end* of that Financial Year, so April 2013.

By using 2012 (whether by accident or design) it conveys the impression that the data is even more out of date and only covers maybe a year or so when the Coalition were in charge, rather than 60% of the current Parliament.

If you are going to criticize the use of statistics by others, then you must take the greatest care that no distortion creeps into your own version – that he has failed to do so critically undermines his argument.

I realize Mr Clarke has a book to sell – it’s actually advertised right there in the article (or “advertising feature” as these things used to be called) and "oops I have no evidence" doesn't help with that, but really this is just hiding from the facts.

Inequality has fallen. This is not because the Tories chose to hit the poor. It’s because the Liberal Democrats chose to defend the poorest-off where we could and to raise fair taxes from the rich.

SSRIs: Much More Than You Wanted To Know

Miri – the person, not the organization – writes about depression. There’s a lot there worth thinking about, but one part caught my eye:

I’m a little tired of being told that SSRIs “don’t work” when they’re part of the reason I didn’t try to off myself four years ago. There is compelling evidence to suggest they do not actually work and there is compelling evidence to suggest that they do actually work, so I’m comfortable saying that the jury’s still out on this one.

I think the jury is less out now than it was a couple of years ago. I think there’s at least kind of a consensus on the data, mixed with a lot of debate over how to express a very complicated reality to the public in a concise way.

And I am going to bypass that debate by just braindumping eight thousand words worth of very complicated reality on you.

The claim that “SSRIs don’t work” or “SSRIs are mostly just placebo” is most commonly associated with Irving Kirsch, a man with the awesome job title of “Associate Director Of The Program For Placebo Studies at Harvard”.

(fun fact: there’s actually no such thing as “Placebo Studies”, but Professor Kirsch’s belief that he directs a Harvard department inspires him to create much higher-quality research.)

In 1998, he published a meta-analysis of 19 placebo-controlled drug trials that suggested that almost all of the benefits of antidepressants were due to the placebo effect. Psychiatrists denounced him, saying that you can choose pretty much whatever studies you want for a meta-analysis.

After biding his time for a decade, in 2008 he struck back with another meta-analysis, this being one of the first papers in all of medical science to take the audacious step of demanding all the FDA’s data through the Freedom of Information Act. Since drug companies are required to report all their studies to the FDA, this theoretically provides a rare and wonderful publication-bias-free data set. Using this set, he found that, although antidepressants did seem to outperform placebo, the effect was not “clinically significant” except “at the upper end of very severe depression”.

This launched a minor war between supporters and detractors. Probably the strongest support he received was a big 2010 meta-analysis by Fournier et al, which found that

The magnitude of benefit of antidepressant medication compared with placebo increases with severity of depression symptoms and may be minimal or nonexistent, on average, in patients with mild or moderate symptoms. For patients with very severe depression, the benefit of medications over placebo is substantial.

Of course, a very large number of antidepressants are given to people with mild or moderate depression. So what now?

Let me sort the debate about antidepressants into a series of complaints:

1. Antidepressants were oversold and painted as having more biochemical backing than was really justified

2. Modern SSRI antidepressants are no better than older tricyclic and MAOI antidepressants, but are prescribed much more because of said overselling

3. There is large publication bias in the antidepressant literature

4. The effect size of antidepressants is clinically insignificant

5. And it only becomes significant in the most severe depression

6. And even the effects found are only noticed by doctors, not the patients themselves

7. And even that unsatisfying effect might be a result of “active placebo” rather than successful treatment

8. And antidepressants have much worse side effects than you have been led to believe

9. Therefore, we should give up on antidepressants (except maybe in the sickest patients) and use psychotherapy instead

1. Antidepressants were oversold and painted as having more biochemical backing than was really justified – Totally true

It is starting to become slightly better known that the standard story – depression is a deficiency of serotonin, antidepressants restore serotonin and therefore make you well again – is kind of made up.

There was never much more evidence for the serotonin hypothesis than that chemicals that increased serotonin tended to treat depression – making the argument that “antidepressants are biochemically justified because they treat the low serotonin that is causing your depression” kind of circular. Saying “Serotonin treats depression, therefore depression is, at root, a serotonin deficiency” is about as scientifically grounded as saying “Playing with puppies makes depressed people feel better, therefore depression is, at root, a puppy deficiency”.

The whole thing became less tenable with the discovery that several chemicals that didn’t increase serotonin were also effective antidepressants – not to mention one chemical, tianeptine, that decreases serotonin. Now the conventional wisdom is that depression is a very complicated disturbance in several networks and systems within the brain, and serotonin is one of the inputs and/or outputs of those systems.

Likewise, a whole bunch of early ’90s claims: that modern antidepressants have no side effects, that they produce miraculous improvements in everyone, that they make you better than well – seem kind of silly now. I don’t think anyone is arguing against the proposition that there was an embarrassing amount of hype that has now been backed away from.

2. Modern SSRI antidepressants are no better than older tricyclic and MAOI antidepressants, but are prescribed much more because of said overselling – First part true, second part less so

Most studies find SSRI antidepressants to be no more effective in treating depression than older tricyclic and MAOI antidepressants. Most studies aren’t really powered to do this. It seems clear that there aren’t spectacular differences, and hunting for small differences has proven very hard.

If you’re a geek about these sorts of things, you know that a few studies have found non-significant advantages for Prozac and Paxil over older drugs like clomipramine, and marginally-significant advantages for Effexor over SSRIs. But conventional wisdom is that tricyclics can be even more powerful than SSRIs for certain very severe hospitalized depression cases, and a lot of people think MAOIs worked better than anything out there today.

But none of this is very important because the real reason SSRIs are so popular is the side effect profile. While it is an exaggeration to say they have no side effects (see above) they are an obvious improvement over older classes of medication in this regard.

Tricyclics had a bad habit of causing fatal arrythmias when taken at high doses. This is really really bad in depression, because depressed people tend to attempt suicide and the most popular method of suicide attempt is overdosing on your pills. So if you give depressed people a pill that is highly fatal in overdose, you’re basically enabling suicidality. This alone made the risk-benefit calculation for tricyclics unattractive in a lot of cases. Add in dry mouth, constipation, urinary problems, cognitive impairment, blurry vision, and the occasional tendency to cause heart arrythmias even when taken correctly, and you have a drug you’re not going to give people who just say they’re feeling a little down.

MAOIs have their own problems. If you’re using MAOIs and you eat cheese, beer, chocolate, beans, liver, yogurt, soy, kimchi, avocados, coconuts, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, you have a chance of precipitating a “hypertensive crisis”, which is exactly as fun as it sounds. As a result, people who are already miserable and already starving themselves are told they can’t eat like half of food. And once again, if you tell people “Eat these foods with this drug and you die” and a week later the person wants to kill themselves and has some cheese in the house, then you’re back to enabling suicide. There are some MAOIs that get around these restrictions in various clever ways, but they tend to be less effective.

SSRIs were the first class of antidepressants that mostly avoided these problems and so were pretty well-placed to launch a prescribing explosion even apart from being pushed by Big Pharma.

3. There is large publication bias in the antidepressant literature – True, but not as important as some people think

People became more aware of publication bias a couple of years after serious research into antidepressants started, and it’s not surprising that these were a prime target. When this issue rose to scientific consciousness, several researchers tried to avoid the publication bias problem by using only FDA studies of antidepressants. The FDA mandates that its studies be pre-registered and the results reported no matter what they are. This provides a “control group” by which accusations of publication bias can be investigated. The results haven’t been good. From Gibbons et al:

Recent reports suggest that efficacy of antidepressant medications versus placebo may be overstated, due to publication bias and less efficacy for mildly depressed patients. For example, of 74 FDA-registered randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 12 antidepressants in 12,564 patients, 94% of published trials were positive whereas only 51% of all FDA registered studies were positive.

Turner et al express the same data a different way:

. The FDA deemed 38 of the 74 studies (51%) positive, and all but 1 of the 38 were published. The remaining 36 studies (49%) were deemed to be either negative (24 studies) or questionable (12). Of these 36 studies, 3 were published as not positive, whereas the remaining 33 either were not published (22 studies) or were published, in our opinion, as positive (11) and therefore conflicted with the FDA’s conclusion. Overall, the studies that the FDA judged as positive were approximately 12 times as likely to be published in a way that agreed with the FDA analysis as were studies with nonpositive results according to the FDA (risk ratio, 11.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 6.2 to 22.0; P

The same source tells us about the effect this bias had on effect size:

For each of the 12 drugs, the effect size derived from the journal articles exceeded the effect size derived from the FDA reviews (sign test, P

I think a lot of this has since been taken on board, and most of the rest of the research I’ll be talking about uses FDA data rather than published data. But as you can see, the overall change in effect size – from 0.31 to 0.41 – is not that terribly large.

4. The effect size of antidepressants is clinically insignificant – Depends what you mean by “clinically insignificant”

As mentioned above, when you try to control for publication bias, the effect size of antidepressant over placebo is 0.31.

This number can actually be broken down further. According to McAllister and Williams, who are working off of slightly different data and so get slightly different numbers, the effect size of placebo is 0.92 and the effect size of antidepressants is 1.24, which means antidepressants have a 0.32 SD benefit over placebo. Several different studies get similar numbers, including the Kirsch meta-analysis that started this whole debate.

Effect size is a hard statistic to work with (albeit extremely fun). The guy who invented effect size suggested that 0.2 be called “small”, 0.5 be called “medium”, and 0.8 be called “large”. NICE, a UK health research group, somewhat randomly declared that effect sizes greater than 0.5 be called “clinically significant” and effect sizes less than 0.5 be called “not clinically significant”, but their reasoning was basically that 0.5 was a nice round number, and a few years later they changed their mind and admitted they had no reason behind their decision.

Despite these somewhat haphazard standards, some people have decided that antidepressants’ effect size of 0.3 means they are “clinically insignificant”.

(please note that “clinically insignificant” is very different from “statistically insignificant” aka “has a p-value less than 0.05.” Nearly everyone agrees antidepressants have a statistically significant effect – they do something. The dispute is over whether they have a clinically significant effect – the something they do is enough to make a real difference to real people)

There have been a couple of attempts to rescue antidepressants by raising the effect size. For example, Horder et al note that Kirsch incorrectly took the difference between the average effect of drugs and the average effect of placebos, rather than the average drug-placebo difference (did you follow that?) When you correct that mistake, the drug-placebo difference rises significantly to about 0.4.

They also note that Kirsch’s study lumps all antidepressants together. This isn’t necessarily wrong. But it isn’t necessarily right, either. For example, his study used both Serzone (believed to be a weak antidepressant, rarely used) and Paxil (believed to be a stronger antidepressant, commonly used). And in fact, by his study, Paxil showed an effect size of 0.47, compared to Serzone’s 0.21. But since the difference was not statistically significant, he averaged them together and said that “antidepressants are ineffective”. In fact, his study showed that Paxil was effective, but when you average it together with a very ineffective drug, the effect disappears. He can get away with this because of the arcana of statistical significance, but by the same arcana I can get away with not doing that.

So right now we have three different effect sizes. 1.2 for placebo + drug, 0.5 for drug alone if we’re being statistically merciful, 0.3 for drug alone if we’re being harsh and letting the harshest critic of antidepressants pull out all his statistical tricks.

The reason effect size is extremely fun is that it allows you to compare effects in totally different domains. I will now attempt to do this in order to see if I can give you an intuitive appreciation for what it means for antidepressants.

Suppose antidepressants were in fact a weight loss pill.

An effect size of 1.2 is equivalent to the pill making you lose 32 lb.

An effect size of 0.5 is equivalent to the pill making you lose 14 lb.

An effect size of 0.3 is equivalent to the pill making you lose 8.5 lb.

Or suppose that antidepressants were a growth hormone pill taken by short people.

An effect size of 1.2 is equivalent to the pill making you grow 3.4 in.

An effect size of 0.5 is equivalent to the pill making you grow 1.4 in.

An effect size of 0.3 is equivalent to the pill making you grow 0.8 in.

Or suppose that antidepressants were a cognitive enhancer to boost IQ. This site gives us some context about occupations.

An effect size of 1.2 is equivalent to the pill making you gain 18 IQ points, ie from the average farm laborer to the average college professor.

An effect size of 0.5 is equivalent to the pill making you gain 7.5 IQ points, ie from the average farm laborer to the average elementary school teacher.

An effect size of 0.3 is equivalent to the pill making you gain 5 IQ points, ie from the average farm laborer to the average police officer.

To me, these kinds of comparisons are a little more revealing than NICE arbitrarily saying that anything below 0.5 doesn’t count. If you could take a pill that helps your depression as much as gaining 1.4 inches would help a self-conscious short person, would you do it? I’d say it sounds pretty good.

5. The effect of antidepressants only becomes significant in the most severe depression – Everything about this statement is terrible and everyone involved should feel bad

So we’ve already found that saying antidepressants have an “insignificant” effect size is kind of arbitrary. But what about the second part of the claim – that they only have measurable effects in “the most severe depression”?

A lot of depression research uses a test called the HAM-D, which scores depression from 0 (none) to 52 (max). Kirsch found that the effect size of antidepressants increased as HAM-D scores increased, meaning antidepressants become more powerful as depression gets worse. He was only able to find a “clinically significant” effect size (d > 0.5) for people with HAM-D scores greater than 28. People have come up with various different mappings of HAM-D scores to words. For example, the APA says:

(0-7) No depression

(8-13) Mild depression

(14-18) Moderate depression

(19-22) Severe depression

(>=23) Very severe depression

Needless to say, a score of 28 sounds pretty bad.

We saw that Horder et al corrected some statistical deficiencies in Kirsch’s original paper which made antidepressants improve slightly. With their methodology, antidepressants reach our arbitrary 0.5 threshold around HAM-D score 26. Another similar “antidepressants don’t work” study got the number 25.

Needless to say, when anything over 23 is “very severe”, 25 or 26 still sounds pretty bad.

Luckily, people completely disagree on the meanings of basic words! Very Severely Stupid is a cute article on Neuroskeptic that demonstrates that five different people and organizations suggest five different systems for rating HAM-D scores. Bech 1996 calls our 26 cutoff “major”; Funakawa 2007 calls it “moderate”; NICE 2009 calls it “severe”. APA is unique in calling it very severe. NICE’s scale is actually the exact same as the APA scale with every category renamed to sound one level less threatening. Facepalm.

Ghaemi and Vohringer(2011) go further and say that the real problem is that Kirsch is using the standard for depressive symptoms, but that real clinical practice involves depressive episodes. That is, all this “no depression” to “severe” stuff is about whether someone can be diagnosed with depression; presumably the people on antidepressants are definitely depressed and we need a new model of severity to determine just how depressed they are. As they put it:

the authors of the meta-analysis claimed to use the American Psychiatric Association’s criteria for severity of symptoms…in so doing, they ignore the obvious fact that symptoms differ from episodes: the typical major depressive episode (MDE) produced HDRS scores of at least 18 or above. Thus, by using symptom criteria, all MDEs are by definition severe or very severe. Clinicians know that some patients meet MDE criteria and are still able to work; indeed others frequently may not even recognize that such a person is clinically depressed. Other patients are so severe they function poorly at work so that others recognize something is wrong; some clinically depressed patients cannot work at all; and still others cannot even get out of bed for weeks or months on end. Clearly, there are gradations of severity within MDEs, and the entire debate in the above meta-analysis is about MDEs, not depressive symptoms, since all patients had to meet MDE criteria in all the studiesincluded in the meta-analysis (conducted by pharmaceutical companies for FDA approval for treatment of MDEs).The question, therefore, is not about severity of depressive symptoms, but severity of depressive episodes, assuming that someone meets DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode. On that question, a number of prior studies have examined the matter with the HDRS and with other depression rating scales, and the three groupings shown in table 2 correspond rather closely with validated and replicated definitions of mild (HDRS 28) major depressive episodes.

So, depending on whether we use APA criteria or G&V criteria, an HRDS of 23 is either “mild” (G&V) or “very severe” (APA).

Clear as mud? I agree that in one sense this is terrible. But in another sense it’s actually a very important point. Kirsch’s sample was really only “severe” in the context of everyone, both those who were clinically diagnosable with major depression and those who weren’t. When we get to people really having a major depressive episode, a score of 26 to 28 isn’t so stratospheric. But meanwhile:

The APA seem to have ignored the fact that the HAMD did not statistically significantly distinguish between “Severe” and “Moderate” depression anyway (p=0.1)

Oh. That gives us some perspective, I guess. Also, some other people make the opposite critique and say that the HAM-D can’t distinguish very well at the low end. Suppose HAM-Ds less than ten are meaningless and random. This would look a lot like antidepressants not working in mild depression.

Getting back to Ghaemi and Vohringer, they try a different tack and suggest that there is a statistical floor effect. They quite reasonably say that if someone had a HAM-D score of 30, and antidepressants solved 10% of their problem, they would lose 3 HAM-D points, which looks impressive. But if someone had a HAM-D score of 10, and antidepressants (still) solved 10% of their problem, they would only lose 1 HAM-D point, which sounds disappointing. But either way, the antidepressants are doing the same amount of work. If you adjust everything for baseline severity, it’s easy to see that antidepressants here would have the same efficacy in severe and mild depression, even though it doesn’t look that way at first.

I am confused that this works for effect sizes, because I expect effect sizes to be relative to the standard deviation in a sample. However, several important people tell me that it does, and that when you do this Kirsch’s effect size goes from 0.32 to 0.40.

(I think these people are saying the exact same thing, but so overly mathematically that I’ve been staring at it for an hour and I’m still not certain)

More important, Ghaemi and Vohringer say once you do this, antidepressants reach the magic 0.5 number not only in severe depression, but also in moderate depression. However, when I look at this claim closely, almost all the work is done by G&V’s adjusted scale in which Kirsch’s “very severe” corresponds to their “mild”.

(personal aside: I got an opportunity to talk to Dr. Ghaemi about this paper and clear up some of my confusion. Well, not exactly an opportunity to talk about it, per se. Actually, he was supposed to be giving me a job interview at the time. I guess we both got distracted. This may be one of several reasons I do not currently work at Tufts.)

So. In conclusion, everyone has mapped HAM-D numbers into words like “moderate” in totally contradictory ways, such that one person’s “mild” is another person’s “very severe”. Another person randomly decided that we can only call things “clinically significant” if they go above the nice round number of 0.5, then retracted this. So when people say “the effects of antidepressants are only clinically significant in severe depression”, what they mean is “the effects of antidepressants only reach a totally arbitrary number one guy made up and then retracted, in people whose HAM-D score is above whatever number I make up right now.” Depending on what number you choose and what word you make up to describe it, you can find that antidepressants are useful in moderate depression, or severe depression, or super-duper double-dog-severe depression, or whatever.

Science!

6. The beneficial effects of antidepressants are only noticed by doctors, not the patients themselves – Partly true but okay

So your HAM-D score has gone down and you’re no longer officially in super-duper double-dog severe depression anymore. What does that mean for the patient?

There are consistent gripes that antidepressant studies that use patients rating their own mood show less improvement than studies where doctors rate how they think a patient is doing, or standardized tests like the HAM-D.

Some people try to turn this into a conspiracy, where doctors who have somehow broken the double-blinding of studies try to report that patients have done better because doctors like medications and want them to succeed.

The reality is more prosaic. It has been known for forty years that people’s feelings are the last thing to improve during recovery from depression.

This might sound weird – what is depression except people’s feelings? But the answer is “quite a lot”. Depressed people often eat less, sleep more, have less energy, and of course are more likely to attempt suicide. If a patient gets treated with an antidepressant, and they start smiling more and talking more and getting out of the house and are no longer thinking about suicide, their doctor might notice – but the patient herself might still feel really down-in-the-dumps.

I am going to get angry comments from people saying I am declaring psychiatric patients too stupid to notice their own recovery or something like that, but it is a very commonly observed phenomenon. Patients have access to internal feelings which they tend to weight much more heavily than external factors like how much they are able to get done during a day or how many crying spells they have, sometimes so much so that they completely miss these factors. Doctors (or family members, or other outside observers) who don’t see these internal feelings, are better able to notice outward signs. As a result, it is pretty universally believed that doctors spot signs of recovery in patients long before the patients themselves think they are recovering. This isn’t just imaginary – it’s found it datasets where the doctors are presumably blinded and with good inter-rater reliability.

Because most antidepressant trials are short, a lot of them reach the point where doctors notice improvement but not the point where patients notice quite as much improvement.

7. The apparent benefits of antidepressant over placebo may be an “active placebo” effect rather than a drug effect – Unlikely

Active placebo is the uncomfortable idea that no study can really have a blind control group because of side effects. That is, sugar pills have no side effects, real drugs generally do, and we all know side effects are how you know that a drug is working!

(there is a counterargument that placebos very often have placebo side effects, but most likely the real drug will at least have more side effects, saving the argument)

The solution is to use active placebo, a drug that has side effects but, as far as anyone knows, doesn’t treat the experimental condition (in this case, depression). The preliminary results from this sort of study don’t look good for antidepressants:

Thomson reviewed 68 double-blind studies of tricyclics that used an inert placebo and seven that used an active placebo (44). He found drug efficacy was demonstrated in 59% of studies that employed inert placebo, but only 14% of those that used active placebo (?2=5.08, df=1, p=0.02). This appears to demonstrate that in the presence of a side-effect-inducing control condition, placebo cannot be discriminated from drug, thus affirming the null hypothesis.

Luckily, Quitkin et al (2000) solve this problem so we don’t have to:

Does the use of active placebo increase the placebo response rate? This is not the case. After pooling data from those studies in which a judgment could be made about the proportion of responders, it was found that 22% of patients (N=69 of 308) given active placebos were rated as responders. To adopt a conservative stance, one outlier study (50) with a low placebo response rate of 7% (N=6 of 90) was eliminated because its placebo response rate was unusually low (typical placebo response rates in studies of depressed outpatients are 25%–35%). Even after removing this possibly aberrant placebo group, the aggregate response rate was 29% (N=63 of 218), typical of an inactive placebo. The active placebo theory gains no support from these data.Closer scrutiny suggests that the “failure” of these 10 early studies to find typical drug-placebo differences is attributable to design errors that characterize studies done during psychopharmacology’s infancy. Eight of the 10 studies had at least one of four types of methodological weaknesses: inadequate sample size, inadequate dose, inadequate duration, and diagnostic heterogeneity. The flaws in medication prescription that characterize these studies are outlined in Table 3. In fact, in spite of design measurement and power problems, six of these 10 studies still suggested that antidepressants are more effective than active placebo.

In summary, these reviews failed to note that the active placebo response rate fell easily within the rate observed for inactive placebo, and the reviewers relied on pioneer studies, the historical context of which limits them.

In other words, active placebo research has fallen out of favor in the modern world. Most studies that used active placebo are very old studies that were not very well conducted. Those studies failed to find an active-placebo-vs.-drug difference because they weren’t good enough to do this. But they also failed to find an active-placebo-vs.-inactive-placebo difference. So they provide no support for the idea that active placebos are stronger than inactive placebos in depression and in fact somewhat weigh against it.

8. Antidepressants have much worse side effects than you were led to believe – Depends how bad you were led to believe the side effects were

As discussed in Part 2, the biggest advantage of SSRIs and other new antidepressants over the old antidepressants was their decreased side effect profile. This seems to be quite real. For example, Brambilla finds a relative risk of adverse events on SSRIs only 60% of that on TCAs, p = 0.003 (although there are some conflicting numbers in that paper I’m not really clear about). Montgomery et al 1994 finds that fewer patients stop taking SSRIs than tricyclics (usually a good “revealed preference”-style measure of side effects since sufficiently bad side effects make you stop using the drug).

The charmingly named Cascade, Kalali, and Kennedy (2009) investigated side effect frequency in a set of 700 patients on SSRIs and found the following:

56% decreased sexual functioning

53% drowsiness

49% weight gain

19% dry mouth

16% insomnia

14% fatigue

14% nausea

13% light-headedness

12% tremor

However, it is very important to note that this study was not placebo controlled. Placebos can cause terrible side effects. Anybody who experiments with nootropics know that the average totally-useless inactive nootropic causes you to suddenly imagine all sorts of horrible things going on with your body, or attribute some of the things that happen anyway (“I’m tired”) to the effects of the pill. It’s not really clear how much of the stuff in this study is placebo effect versus drug effect.

Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that 34% of patients declare side effects “not at all” or “a litte” bothersome, 40% “somewhat” bothersome, and 26% “very” or “extremely” bothersome. That’s much worse than I would have expected.

Aside from the sort of side effects that you expect with any drug, there are three side effects of SSRIs that I consider especially worrisome and worthy of further discussion. These are weight gain, sexual side effects, and emotional blunting.

Weight gain is often listed as one of the most common and debilitating effects of SSRIs. But amusingly, when a placebo-controlled double-blinded study was finally run, SSRIs produced less weight gain than placebo. After a year of pill-taking, people on Prozac had gained 3.1 kg; people on placebo had gained 4.3. There is now some talk of SSRIs as a weak but statistically significant agent for weight loss.

What happened? One symptom of depression is not eating. People get put on SSRIs when they’re really depressed. Then they get better, either because the drugs worked, because of placebo, or just out of regression to the mean. When you go from not eating to eating, you gain weight. In the one-year study, almost everyone’s depression remitted (even untreated depressive episodes rarely last a whole year), so everyone went from a disease that makes them eat less, to remission from that disease, so everyone gained weight.

Sexual side effects are a less sanguine story. Here the direction was opposite: the medical community went from thinking this was a minor problem to finding it near-universal. The problem was that doctors usually just ask “any side effects?”, and off Tumblr people generally don’t volunteer information about their penis or vagina to a stranger. When they switched to the closed-ended question “Are you having any sexual side effects?”, a lot of people who denied side effects in general suddenly started talking.

Numbers I have heard for the percent of people on SSRIs with sexual side effects include 14, 24, 37, 58, 59, and 70 (several of those come from here. After having read quite a bit of this research, I suspect you’ve got at least a 50-50 chance (they say men are more likely to get them, but they’re worse in women). Of people who develop sexual side effects, 40% say they caused serious distress, 35% some distress, and 25% no distress.

So I think it is fair to say that if you are sexually active, your chances with SSRIs are not great. Researchers investigating the topic suggest people worried about sexual side effects should switch to alternative sexual-side-effect-free antidepressant Serzone. You may remember that as the antidepressant that worked worst in the efficacy studies and brought the efficacy of all the other ones down with it. Also, it causes liver damage. In my opinion, a better choice would be bupropion, another antidepressant which has been found many times not to cause sexual side effects and which may even improve your sex life.

(“Bupropion lacks this side effect” is going to be a common theme throughout this section. Bupropion causes insomnia, decreased appetite, and in certain rare cases of populations at risk, seizures. It is generally a good choice for people who are worried about SSRI side effects and would prefer a totally different set of side effects.)

There is a certain feeling that, okay, these drugs may have very very common, possibly-majority-of-user sexual side effects, but depressed people probably aren’t screwing like rabbits anyway. So after you recover, you can wait the appropriate amount of time, come off the drugs (or switch to a different drug or dose for maintenance) and no harm done.

The situation no longer seems so innocuous. Despite a lack of systematic investigation, there are multiple reports from researchers and clinicians – not to mention random people on the Internet – of permanent SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction that does not remit once the drug is stopped. This is definitely not the norm and as far as we know it is so rare as to be unstudyable beyond the occasional case report.

On the other hand, I have this. I took SSRIs for about five to ten years as a kid, and now I have approximately the pattern of sexual dysfunction associated with SSRIs and consider myself asexual. Because I started the SSRIs too early to observe my sexuality without them, I can’t officially blame the drugs. But I am very suspicious. I feel like this provides moderate anthropic evidence that it is not as rare as everyone thinks.

The last side effect worth looking at is emotional blunting. A lot of people say they have trouble feeling intense emotions (sometimes: any emotions at all) when on SSRIs. Sansone and Sansone (2010) report:

As for prevalence rates, according to a study by Bolling and Kohlenberg, approximately 20 percent of 161 patients who were prescribed an SSRI reported apathy and 16.1 percent described a loss of ambition. In a study by Fava et al, which consisted of participants in both the United States and Italy, nearly one-third on any antidepressant reported apathy, with 7.7 percent describing moderate-to-severe impairment, and nearly 40 percent acknowledged the loss of motivation, with 12.0 percent describing moderate-to-severe impairment.

A practicing clinician working off observation finds about the same numbers:

The sort of emotional “flattening” I have described with SSRIs may occur, in my experience, in perhaps 10-20% of patients who take these medications…I do want to emphasize that most patients who take antidepressant medication under careful medical supervision do not wind up feeling “flat” or unable to experience life’s normal ups and downs. Rather, they find that–in contrast to their periods of severe depression–they are able to enjoy life again, with all its joys and sorrows.

Many patients who experience this side effect note that when you’re depressed, “experiencing all your emotions fully and intensely” is not very high on your list of priorities, since your emotions tend to be terrible. There is a subgroup of depressed patients whose depression takes the form of not being able to feel anything at all, and I worry this effect would exacerbate their problem, but I have never heard this from anyone and SSRIs do not seem less effective in that subgroup, so these might be two different things that only sound alike. A couple of people discussing this issue have talked about how decreased emotions help them navigate interpersonal relationships that otherwise might involve angry fights or horrible loss – which sounds plausible but also really sad.

According to Barnhart et al (2004), “this adverse effect has been noted to be dose-dependent and reversible” – in other words, it will get better if you cut your dose, and go away completely when you stop taking the medication. I have not been able to find any case studies or testimonials by people who say this effect has been permanent.

My own experience was that I did notice this (even before I knew it was an official side effect) that it did go away after a while when I stopped the medications, and that since my period of antidepressant use corresponded with an important period of childhood socialization I ended out completely unprepared for having normal emotions and having to do a delicate social balancing act while I figured out how to cope with them. Your results may vary.

There is also a large research on suicidality as a potential side effect of SSRIs, but this looks like it would require another ten thousand words just on its own, so let’s agree it’s a risk and leave it for another day.

9. Therefore, we should give up on medication and use psychotherapy instead – Makes sense right up until you run placebo-controlled trials of psychotherapy

The conclusion of these studies that claim antidepressants don’t outperform placebo is usually that we should repudiate Big Pharma, toss the pills, and go back to using psychotherapy.

The implication is that doctors use pills because they think they’re much more effective than therapy. But that’s not really true. The conventional wisdom in psychiatry is that antidepressants and psychotherapy are about equally effective.

SSRIs get used more than psychotherapy for the same reason they get used more than tricyclics and MAOIs – not because they’re better but because they have fewer problems. The problem with psychotherapy is you’ve got to get severely mentally ill people to go to a place and talk to a person several times a week. Depressed people are not generally known for their boundless enthusiasm for performing difficult tasks consistently. Also, Prozac costs like 50 cents a pill. Guess how much an hour of a highly educated professional’s time costs? More than 50c, that’s for sure. If they are about equal in effectiveness, you probably don’t want to pay extra and your insurance definitely doesn’t want to pay extra.

Contrary to popular wisdom, it is almost never the doctor pushing pills on a patient who would prefer therapy. If anything it’s more likely to be the opposite.

However, given that we’re acknowledging antidepressants have an effect size of only about 0.3 to 0.5, is it time to give psychotherapy a second look?

No. Using very similar methodology, a team involving Mind The Brain blogger James Coyne found that psychotherapy decreases HAM-D scores by about 2.66, very similar to the 2.7 number obtained by re-analysis of Kirsch’s data on antidepressants. It concludes:

Although there are differences between the role of placebo in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy research, psychotherapy has an effect size that is comparable to that of antidepressant medications. Whether these effects should be deemed clinically relevant remains open to debate.

Another study by the same team finds psychotherapy has an effect size of 0.22 compared to antidepressants’ 0.3 – 0.5, though no one has tried to check if that difference is statistically significant and this does not give you the right to say antidepressants have “outperformed” psychotherapy.

If a patient has the time, money, and motivation for psychotherapy, it may be a good option – though I would only be comfortable using it as a monotherapy if the depression was relatively mild.

10. Further complications

What if the small but positive effect size of antidepressants wasn’t because they had small positive effects on everyone, but because they had very large positive effects on some people, and negative effects on others, such that it averaged out to small positive effects? This could explain the clinical observations of psychiatrists (that patients seem to do much better on antidepressants) without throwing away the findings of researchers (that antidepressants have only small benefits over placebo) by bringing in the corollary that some psychiatrists notice some patients doing poorly on antidepressants and stop them in those patients (which researchers of course would not do).

This is the claim of Gueorguieva and Krystal 2011, who used “growth modeling” to analyze seven studies of new-generation-antidepressant Cymbalta and found statistically significant differences between two “trajectories” for the drug, but not for placebo. 66% of people were in the “responder” trajectory and outperformed placebo by 6 HAM-D points (remember, previous studies estimated HAM-D benefits over placebo at about 2.7). 33% of people were nonresponders and did about 6 HAM-D points worse than placebo. Average it out, and people did about 3 HAM-D points better on drug and placebo, pretty close to the previous 2.7 point estimate.

I don’t know enough about growth modeling to be sure that the researchers didn’t just divide the subjects into two groups based on treatment efficacy and say “Look! The subsection of the population whom we selected for doing well did well!” but they use many complicated statistics words throughout the study that I think are supposed to indicate they’re not doing this.

If true, this is very promising. It means psychiatrists who are smart enough to notice people getting worse on antidepressants can take them off (or switch to another class of medication) and expect the remainder to get much, much better. I await further research with this methodology.

What if there were actually no such thing as the placebo effect? I know dropping this in around the end of an essay that assumes 75% of gains related to antidepressants are due to the placebo effect is a bit jarring, but it is the very-hard-to-escape conclusion of Hróbjartsson and Gøtzsche’s meta-analysis on placebo. They find that three-armed studies – ie those that have a no-treatment group, a placebo-treatment group, and a real-drug-treatment group – rarely find much of a difference between no-treatment and placebo. This was challenged by Wampold et al here and here, but defended against those challenges by the long-name-Scandinavian-people here. Kirsch, who between all his antidepressant work is still Associate Director of Placebo Studies, finds here that 75% of the apparent placebo effect in antidepressant studies is probably a real placebo effect, but his methodology is a valiant attempt to make the most out of a total lack of data rather than a properly-directed study per se.

If placebo pills don’t do much, what explains the vast improvements seen in both placebo and treatment groups in antidepressant trials? It could be the feeling of cared-for-ness and special-ness of getting to see a psychiatrist and talk with her about your problems, and the feeling of getting-to-contribute-something you get from participating in a scientific study. Or it could just be regression to the mean – most people start taking drugs when they feel very depressed, and at some point you have nowhere to go but up. Most depression gets better after six months or so – which is a much longer period than the six week length of the average drug trial, but maybe some people only volunteered for the study four months and two weeks after their depression started.

If Hróbjartsson and Gøtzsche were right, and Kirsch and the psychiatric establishment wrong, what would be the implications? Well, the good implication is that we no longer have to worry about problem 7 – that antidepressants are merely an active placebo – since active placebos shouldn’t do anything. That means we can be more confident they really work. The more complicated implication is that psychiatrists lose one excuse for asking people to take the drugs – “Sure, the drug effect may be small, but the placebo effect is so strong that it’s still worth it.” I don’t know how many psychiatrists actually think this way, but I sometimes think this way.

What if the reason people have so much trouble finding good effects from antidepressants is that they’re giving the medications wrong? Psychiatric Times points out that:

The Kirsch meta-analysis looked only at studies carried out before 1999. The much-publicized Fournier study examined a total of 6 antidepressant trials (n=718) using just 2 antidepressants, paroxetine and imipramine. Two of the imipramine studies used doses that were either subtherapeutic (100 mg/day) or less than optimal (100 to 200 mg/day)

What if we’ve forgotten the most important part? Antidepressants are used not only to treat acute episodes of depression, but to prevent them from coming back (maintenance therapy). This they apparently do very well, and I have seen very few studies that attempt to call this effect into question. Although it is always possible that someone will find the same kind of ambiguity around maintenance antidepressant treatment as now clouds acute antidepressant treatment, so far as far as I know this has not happened.

What if we don’t understand what’s going on with the placebo effect in our studies? Placebo effect has consistently gotten stronger over the past few decades, such that the difference between certain early tricyclic studies (which often found strong advantages for the medication) and modern SSRI studies (which often find only weak advantages for the medication) is not weaker medication effect, but stronger placebo effect (that is, if medication always has an effect of 10, but placebo goes from 0 to 9, apparent drug-placebo difference gets much lower). Wired has a good article on this. Theories range from the good – drug company advertising and increasing prestige and awareness of psychiatry have raised people’s expectations of psychiatric drugs – to the bad – increasing scientific competence and awareness have improved blinding and other facets of trial design – to the ugly – modern studies recruit paid participants with advertisements, so some unscrupulous people may be entering studies and then claiming to get better, hoping that this sounds sufficiently like the outcome the researchers want that everyone will be happy and they’ll get their money on schedule.

If placebos are genuinely getting better because of raised expectations, that’s good news for doctors and patients but bad news for researchers and drug companies. The patient will be happy because they get better no matter how terrible a prescribing decision the doctor makes; the doctor will be happy because they get credit. But for researchers and drug companies, it means it’s harder to prove a difference between drug and placebo in a study. You can invent an excellent new drug and still have it fail to outperform placebo by very much if everyone in the placebo group improves dramatically.

Conclusion

An important point I want to start the conclusion section with: no matter what else you believe, antidepressants are not literally ineffective. Even the most critical study – Kirsch 2008 – finds antidepressants to outperform placebo with p

An equally important point: everyone except those two Scandinavian guys with the long names agree that, if you count the placebo effect, antidepressants are extremely impressive. The difference between a person who gets an antidepressant and a person who gets no treatment at all is like night and day.

The debate takes place within the bounds set by those two statements.

Antidepressants give a very modest benefit over placebo. Whether this benefit is so modest as to not be worth talking about depends on what level of benefits you consider so modest as to not be worth talking about. If you are as depressed as the average person who participates in studies of antidepressants, you can expect an antidepressant to have an over-placebo-benefit with an effect size of 0.3 to 0.5. That’s the equivalent of a diet pill that gives you an average weight loss of 9 to 14 pounds, or a growth hormone that makes you grow on average 0.8 to 1.4 inches.

You may be able to get more than that if you focus on the antidepressants, like paroxetine and venlafaxine, that perform best in studies, but we don’t have the statistical power to say that officially. It may be the case that most people who get antidepressants do much better than that but a few people who have paradoxical negative responses bring down the average, but right now this result has not been replicated.

This sounds moderately helpful and probably well worth it if the pills are cheap (which generic versions almost always are) and you are not worried about side effects. Unfortunately, SSRIs do have some serious side effects. Some of the supposed side effects, like weight gain, seem to be mostly mythical. Others, like sexual dysfunction, seem to be very common and legitimately very worrying. You can avoid most of these side effects by taking other antidepressants like bupropion, but even these are not totally side-effect free.

Overall I think antidepressants come out of this definitely not looking like perfectly safe miracle drugs, but as a reasonable option for many people with moderate (aka “mild”, aka “extremely super severe”) depression, especially if they understand the side effects and prepare for them.

Some rambling thoughts on region restrictions

I think at this point in the century, everyone reading this blog—with the [possible] exception of certain lurkers who are required by virtue of their position within their company to toe the Party Line and therefore may not be free to say what they really think—is clear on the drawbacks of DRM.

But regional restrictions make me wince, because from an author's point of view the situation is a bit more complicated.