Lexaloffle Games' PICO-8 "fantasy console" is going to get a physical, handheld version when it ships pre-installed (with a library of built-in games) on Next Thing's $49 PocketCHIP handheld computer. ...

Lexaloffle Games' PICO-8 "fantasy console" is going to get a physical, handheld version when it ships pre-installed (with a library of built-in games) on Next Thing's $49 PocketCHIP handheld computer. ...

Taylor Swift

Shared posts

PICO-8 'fantasy console' to become an actual handheld console -- sort of

#1219; The Connotation Competition

City Hall raises a trans flag

John Keith shows us the new flag flying in front of City Hall - in support of rights for transgender residents. Mayor Walsh and other city officials raised the flag yesterday.

Nintendo bringing Animal Crossing and Fire Emblem to mobile

Taylor Swift:SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF: :SIREN.GIF:

The Singles Jukebox is seeking new writers

Taylor SwiftI've been thinking about applying to this for awhile and my undying hatred of Inskeep might push me over the edge

The Singles Jukebox is home to a talented roster of writers from around the globe with passionate, critical voices dedicated to the spectrum of modern music. We are an unpaid collective with a friendly community and many writers and alumni writing professionally elsewhere. If you’re a writer interested in exploring diverse genres and unfamiliar sounds we want to hear from you.

The site is seeking applications from writers with bold ideas and a willingness to tackle new subjects. We are particularly interested in writers whose voices are under-represented in music criticism and strongly encourage women and people of color to apply. All are welcome to apply, including those who have previously expressed interest in writing for the website.

If you’d like to be considered, please submit the following as an email to info@thesinglesjukebox.com (no attachments, please) by midnight at the end of May 15th:

1. Two blurbs on songs of your choosing from the following list:

- Calibre 50 – Préstamela a Mí

- Ingrid – Double Pedigree

- Jana Hermann – Kults

- Kungs vs. Cookin’ on 3 Burners – This Girl

- Lali – Único

- Madeintyo – Uber Everywhere

- Margo Price – Hurtin’ (On the Bottle)

- Onuka – Vidlik

- OT Genasis ft. Young Dolph – Cut It

2. A blurb on one of your least favorite songs of the year so far.

3. A blurb on a song from this year that we haven’t covered.

4. A sample of your writing — this could be anything from a published review to a blog post you’re proud of, anything you think represents the best of your work. If you don’t have anything suitable, please add a blurb for a third song from the list.

All blurbs should be up to 250 words of clean, concise copy and include a score from 0-10 that is well justified by the writing. If you have questions, send an email to info@thesinglesjukebox.com. All submissions will be considered, and we will respond to all applicants.

Officer's gun goes off by mistake in Jamaica Plain; police investigating

Taylor SwiftLocal officer said to be "grieving" over rotation of seasonal sandwiches

The scene from inside City Feed and Supply.

Around 2 p.m. on Seaverns Avenue, just off Centre Street.

P. Cheung forwarded a friend's photo from inside City Feed.

John Hayden forwards a report from the local neighborhood watch - that an officer's gun went off accidentally and that nobody was hit. Boston Police are investigating the incident.

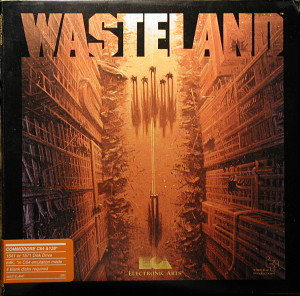

Wasteland

Taylor SwiftHere is a really great example of how to do a lot of great research work, expend a lot of energy on making a complex subject readable and understandable, and then shoot yourself in both feet and the ass by tripling down on deadnaming some of the greatest computer game engineers of the 1980s for fucking "historical anachronism"'s sake. DON'T DO THIS!!!!!

We can mark the formal beginning of the Wasteland project to the day in December of 1985 when Brian Fargo, head of Interplay, flew out to Arizona with his employee Alan Pavlish to meet with Michael Stackpole. If all went well at the meeting, Pavlish was to join Stackpole and Ken St. Andre as the third member of the core trio who would guide the game to release. His role, however, would be very different from that of his two colleagues.

A hotshot programmer’s programmer, Pavlish, though barely twenty years old, had been kicking around the industry for several years already. Before Interplay existed, he’d done freelance work on Commodore VIC-20 games for their earlier incarnation as Boone Corporation, and done ports of games like Murder on the Zinderneuf to the Apple II and Commodore 64 for another little company called Designer Software. When Pavlish came to work for Interplay full-time, Fargo had first assigned him to similar work: he had ported the non-Interplay game Hacker to the Apple II for Activision. (In those pre-Bard’s Tale days, Fargo was still forced to accept such unglamourous work to make ends meet.) But Fargo had huge respect for Pavlish’s abilities. When the Wasteland idea started to take off while his usual go-to programming ace Bill Heineman1 was still swamped with the Bard’s Tale games and Interplay’s line of illustrated text adventures, Fargo didn’t hesitate to throw Pavlish in at the deep end: he planned to make him responsible for bringing the huge idea that was Wasteland to life on the little 64 K 8-bit Apple II and Commodore 64.

However, when Fargo and Pavlish got out of their airplane that day it was far from certain that there would be a Wasteland project for Pavlish to work on at all. In contrast to St. Andre, Stackpole was decidedly skeptical, and for very understandable reasons. His experiences with computer-game development to date hadn’t been happy ones. Over the past several years, he’d been recruited to three different projects and put considerable work into each, only to see each come to naught in one way or another. Thanks largely to the influence of Paul Jaquays,2 another tabletop veteran who headed Coleco’s videogame-design group during the first half of the 1980s, he’d worked on two games for the Coleco Adam, a would-be challenger in the home-computer wars. The more intriguing of the two, a Tunnels & Trolls adaptation, got cancelled before release. The other, an adaptation of the film 2010: Odyssey Two, was released only after the Adam had flopped miserably and been written off by Coleco; you can imagine how well that game sold. He’d then accepted a commission from science-fiction author cum game developer Fred Saberhagen to design a computer game that took place in the world of the latter’s Book of Swords trilogy. (Stackpole had already worked with Flying Buffalo on a board game set in the world of Saberhagen’s Berserker series.) The computerized Book of Swords had gone into stasis when it became clear that Berserker Works, the development company Saberhagen had founded, just didn’t have the resources to finish it.

So, yes, Stackpole needed some convincing to jump into the breach again with tiny Interplay, a company he’d never heard of.3 Luckily for Interplay, he, Fargo, and Pavlish all got along like a house on fire on that December day. Fargo and Pavlish persuaded Stackpole that they shared — or at least were willing to accommodate — his own emerging vision for Wasteland, for a computer game that would be a game and a world first, a program second. Stackpole:

Programmers design beautiful programs, programs that work easily and simply; game designers design games that are fun to play. If a programmer has to make a choice between an elegant program and a fun game element, you’ll have an elegant program. You need a game designer there to say, “Forget how elegant the program is — we want this to make sense, we want it to be fun.”

I was at a symposium where there were about a dozen people. When asked to tell what we were doing, what I kept hearing over and over from programmer/game designers was something like “I’ve got this neat routine for packing graphics, so I’m going to do a fantasy role-playing game where I can use this routine.” Or a routine for something else, or “I’ve got a neat disk sort,” or this or that. And all of them were putting these into fantasy role-playing games. Not to denigrate their skills as programmers — but that’s sort of like saying, “Gee, I know something about petrochemicals, therefore I’m going to design a car that will run my gasoline.” Well, if you’re not a mechanical engineer, you don’t design cars. You can be the greatest chemist in the world, but you’ve got no business designing a car. I’d like to hope that Wasteland establishes that if you want a game, get game designers to work with programmers.

This vision, cutting as it does so much against the way that games were commonly made in the mid-1980s, would have much to do with both where the eventual finished Wasteland succeeds and where it falls down.

Ditto the game’s tabletop heritage. As had been Fargo’s plan from the beginning, Wasteland‘s rules would be a fairly faithful translation of Stackpole’s Mercenaries, Spies, and Private Eyes tabletop RPG, which was in turn built on the foundation of Ken St. Andre’s Tunnels & Trolls. A clear evolutionary line thus stretched from the work that St. Andre did back in 1975 to Wasteland more than a decade later. No CRPG to date had tried quite as earnestly as Wasteland would to bring the full tabletop experience to the computer.

You explore the world of Wasteland from a top-down perspective instead of the first-person view of The Bard’s Tale. Note that this screenshot and the ones that follow come from the slightly later (and vastly more pleasant to play) MS-DOS port rather than the 8-bit original.

Early in the new year, Stackpole and St. Andre visited Interplay’s California offices for a week to get the process of making Wasteland rolling. St. Andre arrived with a plot already dreamed up. Drawing heavily from the recent ultra-violent action flick Red Dawn, it posited a world where mutually-assured destruction hadn’t proved so mutual after all: the Soviet Union had won the war, and was now occupying the United States. The player would control a group of American freedom fighters skulking around the farmlands of Iowa, trying to build a resistance network. St. Andre and Stackpole spent a month or more after their visit to California drawing maps of cornfields and trying to find ways to make an awful lot of farmers seem different from one another. (Some of this work can be seen in the Agricultural Center in the finished Wasteland.) But finally the pair had to accept the painful truth: the game they were designing was boring. “I said it will be the dullest game you ever saw,” remembers St. Andre, “because the Russians would be there in strength, and your characters start weak and can’t do anything but skulk and hide and slowly, slowly build up.”

St. Andre suggested moving the setting to the desert of the American Southwest, an area with which he, being born and raised in Arizona, was all too familiar. The region also had a certain thematic resonance, being intimately connected with the history of the atomic bomb. The player’s party might even visit Las Vegas, where folks had once sat on their balconies and watched the mushroom clouds bloom. St. Andre suggested nixing the Soviets as well, replacing them with “ravening monsters stalking through a radioactive wasteland, a few tattered humans struggling to survive against an overwhelming threat.” It meant chucking a fair amount of work, but Fargo agreed that it sounded too good to pass up. They might as well all get used to these sorts of false starts. Little would go smoothly or according to plan on this project.

After that first week at Interplay, St. Andre and Stackpole worked from home strictly in a design role, coming up with the plans for the game that were then left to Pavlish in California to implement in code — still an unusual way of working in the mid-1980s, when even many of the great designers, like Dan Bunten4 and Sid Meier, tended to also be great programmers. But St. Andre and Stackpole used their computers — a Commodore 64 in the case of the former, a battered old Osborne luggable in that of the latter — to do nothing more complex than run a word processor. Bundle after bundle of paper was shipped from Arizona to California, in the form of both computer printouts and reams of hand-drawn maps. St. Andre and Stackpole worked, in other words, largely the same way they would have had Wasteland been planned as a new tabletop adventure module.

Wasteland must be, however, one hell of a big adventure module. It soon became clear that the map-design process, entailing as it did the plotting of every single square with detailed descriptions of what it contained and what the party should be able to do there, was overwhelming the two. St. Andre:

I hadn’t thought a great deal about what was going to be in any of these places. I just had this nebulous story in my mind: our heroes will start in A, they’ll visit every worthwhile place on the map and eventually wind up in Z — and if they’re good enough, they’ll win the game. Certain things will be happening in different locations — monsters of different types, people who are hard to get along with, lots of comic references to life before the war. I figured that when the time came for me to design an area, the Indian Village, for example, I would sit down and figure out what would be in it and that would be it. Except that it started taking a long time. Every map had 1024 squares on it, and each one could do something. Even if I just drew all the buildings, I had to go back and say, “These are all square nine: wall, wall, wall, wall, wall. And if you bump into a wall you’ll get this message: ‘The Indians are laughing at you for walking into a wall.'” Whatever — a map that I thought I could toss off in one or two days was taking two weeks, and the project was falling further and further behind.

Fargo agreed to let St. Andre and Stackpole bring in their old Flying Buffalo buddies Liz Danforth and Dan Carver to do maps as well, and the design team just continued to grow from there. “The guys who were helping code the maps, correcting what we sent in, wanted to do some maps,” remembers Stackpole. “Everyone wanted to have his own map, his own thumbprint on the game.”

Even Fargo himself, who could never quite resist the urge to get his own hands dirty with the creations of this company he was supposed to be running from on high, begged for a map. “I want to do a map. Let me have Needles,” St. Andre remembers him saying. “So I said, ‘You’re the boss, Brian, you’ve got Needles.'” But eventually Fargo had to accept that he simply didn’t have the time to design a game and run a company, and the city of Needles fell to another Interplay employee named Bruce Balfour. In all, the Wasteland manual credits no fewer than eight people other than St. Andre and Stackpole with “scenario design.” Even Pavlish, in between trying to turn this deluge of paper into code, managed to make a map or two of his own.

Wasteland is one of the few computer games in history in which those who worked on the softer arts of writing and design outnumbered those who wrote the code and drew the pictures. The ratio isn’t even close: the Wasteland team included exactly one programmer (Pavlish) and one artist (Todd J. Camasta) to go with ten people who only contributed to the writing and design. One overlooked figure in the design process, who goes wholly uncredited in the game’s manual, was Joe Ybarra, Interplay’s liaison with their publisher Electronic Arts. As he did with so many other classic games, Ybarra offered tactful advice and generally did his gentle best to keep the game on course, even going so far as to fly out to Arizona to meet personally with St. Andre and Stackpole.

Those two found themselves spending as much time coordinating their small army of map designers as they did doing maps of their own. Stackpole:

Work fell into a normal pattern. Alan and I would work details out, I’d pass it down the line to the folks designing maps. If they had problems, they’d tell me, Alan and I would discuss things, and they’d get an answer. In this way the practical problems of scenario design directly influenced the game system and vice versa. Map designers even talked amongst themselves, sharing strategies and some of these became standard routines we all later used.

Stackpole wound up taking personal responsibility for the last third or so of the maps, where the open world begins funneling down toward the climax. St. Andre:

I’m fairly strong at making up stories, but not at inventing intricate puzzles. In the last analysis, I’m a hack-and-slash gamer with only a little thought and strategy thrown in. Interplay and Electronic Arts wanted lots of puzzles in the game. Mike, on the other hand, is much more devious, so I gave him the maps with difficult puzzles and I did the ones that involved walking around, talking to people, and shooting things.

The relationship between these two veteran tabletop designers and Pavlish, the man responsible for actually implementing all of their schemes, wasn’t always smooth. “We’d write up a map with all the things on it and then Alan would say, ‘I can’t do that,'” says St. Andre. There would then follow some fraught discussions, doubtless made still more fraught by amateur programmer St. Andre’s habit of declaring that he could easily implement what was being asked in BASIC on his Commodore 64. (Stackpole: “It’s like a duffer coming up to Arnold Palmer at an average golf course and saying, ‘What do you mean you can’t make that 20-foot putt? I can make a 20-foot putt on a miniature golf course.'”) One extended battle was over the question of grenades and other “area-effect” weapons: St. Andre and Stackpole wanted them, Pavlish said they were just too difficult to code and unnecessary anyway. Unsung hero Joe Ybarra solved that one by quietly lobbying Fargo to make sure they went in.

One aspect of Wasteland that really demonstrates St. Andre and Stackpole’s determination to divorce the design from the technology is the general absence of the usual numbers that programmers favor — i.e., the powers of two that fit so neatly into the limited memories of the Apple II and Commodore 64. Pavlish instinctively wanted to make the two types of pistols capable of holding 16 or 32 bullets. But St. Andre and Stackpole insisted that they hold 7 or 18, just like their real-world inspirations. As demonstrated by the 1024-square maps, the two did occasionally let Pavlish get away with the numbers he favored, but they mostly stuck to their guns (ha!). “It’s going to be inelegant in terms of space,” admits Stackpole, “but that’s reality.”

Logic like this drove Pavlish crazy, striving as he was to stuff an unprecedentedly complex world into an absurdly tiny space. Small wonder that there were occasional blowups. Slowly he learned to give every idea that came from the designers his very best try, and the designers learned to accept that not everything was possible. With that tacit agreement in place, the relationship improved. In the latter stages of the project, St. Andre and Stackpole came to understand the technology well enough to start providing their design specifications in code rather than text. “Then we could put in the multiple saving throws, the skill and attribute checks,” says St. Andre. “Everything we do in a [Tunnels & Trolls] solitaire dungeon suddenly pops up in the last few maps we did for Wasteland because Mike and I were doing the actual coding.”

When not working on the maps, St. Andre and Stackpole — especially the latter, who came more and more to the fore as time went on — were working on the paragraph book that would contain much of Wasteland‘s story and flavor text. The paragraph book wasn’t so much a new idea as a revival of a very old one. Back in 1979, Jon Freeman’s Temple of Apshai, one of the first CRPGs to arrive on microcomputers, had included a booklet of “room descriptions” laid out much like a Dungeons & Dragons adventure module. This approach was necessitated by the almost unbelievably constrained system for which Temple of Apshai was written: a Radio Shack TRS-80 with just 16 K of memory and cassette-based storage. Moving into the late 1980s, the twilight years of the 8-bit CRPG, designers were finding the likes of the Apple II and Commodore 64 as restrictive as Freeman had the TRS-80 for the simple reason that, while the former platforms may have had four times as much memory as the latter, CRPG design ambitions had grown by at least the same multiple. Moving text, a hugely expensive commodity in terms of 8-bit storage, back into an accompanying booklet was a natural remedy. Think of it as one final measure to wring just a little bit more out of the Apple II and Commodore 64, those two stalwart old warhorses that had already survived far longer than anyone had ever expected. And it didn’t hurt, of course, that a paragraph book made for great copy protection.

While the existence of a Wasteland paragraph book in itself doesn’t make the game unique, St. Andre and Stackpole were almost uniquely prepared to use theirs well, for both had lots of experience crafting Tunnels & Trolls solo adventures. They knew how to construct an interactive story out of little snippets of static text as well as just about anyone, and how to scramble it in such a way as to stymie the cheater who just starts reading straight through. Stackpole, following a tradition that began at Flying Buffalo, constructed for the booklet one of the more elaborate red herrings in gaming history, a whole alternate plot easily as convoluted as that in the game proper involving, of all things, a Martian invasion. All told, the Wasteland paragraph book would appear to have easily as many fake entries as real ones.

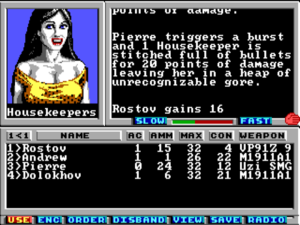

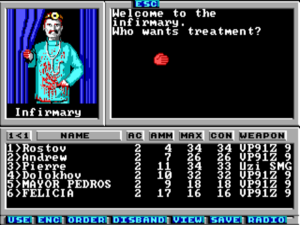

For combat, the display shifts back to something very reminiscent of The Bard’s Tale, with the added tactical dimension of a map showing everyone’s location that you can access by tapping the space bar. And yes, you fight some strange foes in Wasteland…

Wasteland‘s screen layout often resembles that of The Bard’s Tale, and one suspects that there has to be at least a little of the same code hidden under its hood. In the end, though, the resemblance is largely superficial. There’s just no comparison in terms of sophistication. While it’s not quite a game I can love — I’ll try to explain why momentarily — Wasteland does unquestionably represent the bleeding edge of CRPG design as of its 1988 release date. CRPGs on the Apple II and Commodore 64 in particular wouldn’t ever get more sophisticated than this. Given the constraints of those platforms, it’s honestly hard to imagine how they could.

Key to Wasteland‘s unprecedented sophistication is its menu of skills. Just like in Mercenaries, Spies, and Private Eyes, you can tailor each of the up to four characters in your party as you will, free from the restrictive class archetypes of Dungeons & Dragons (or for that matter Tunnels & Trolls). Skills range from the obviously useful (Clip Pistol, Pick Lock, Medic) to the downright esoteric (Metallurgy, Bureaucracy, Sleight of Hand). And of course career librarian St. Andre made sure that a Librarian skill was included, and of course made it vital to winning the game.

Also as in Mercenaries, Spies, and Private Eyes, a character’s chance of succeeding at just about anything is determined by adding her level in a relevant skill, if any, to a relevant core attribute. For example, to determine a character’s chance of climbing something using her Climb skill the game will also look to her Agility. The system allows a range of solutions to most of the problems you encounter. Say you come to a locked door. You might have a character with the Pick Lock skill try getting in that way. Failing that, a character with the Demolition skill and a little handy plastic explosives could try blasting her way in. Or a strong character might dispense with skills altogether and just try to bash the door down using her Strength attribute. Although a leveling mechanism does exist that lets you assign points to characters’ skills and attributes, skills also improve naturally with use, a mechanism not seen in any previous CRPG other than Dungeon Master (a game that’s otherwise about as different from Wasteland as a game can be and still be called a CRPG).

The skills system makes Wasteland a very different gameplay experience from Ultima V, its only real rival in terms of 8-bit CRPG sophistication at the time of its release. For all its impressive world-building, Ultima V remains bound to Richard Garriott’s standard breadcrumb-trail philosophy of design; beating it depends on ferreting out a long string of clues telling you exactly where to go and exactly what to do. Wasteland, by contrast, can be beaten many ways. If you can’t find the password the guard wants to let you past that locked gate, you can try an entirely different approach: shoot your way in, blow the gate open, pick the lock on the back door and sneak in. It’s perhaps the first CRPG ever that’s really willing to let you develop your own playing personality. You can approach it as essentially a post-apocalyptic Bard’s Tale, making a frontal assault on every map and trying to blow away every living creature you find there, without concerning yourself overmuch about whether it be good or evil, friend or foe. Or you can play it — relatively speaking — cerebrally, trying to use negotiations, stealth, and perhaps a little swindling to get what you need. Or you can be like most players and do a bit of both, as the mood and opportunity strikes you. It’s very difficult if not impossible to get yourself irretrievably stuck in Wasteland. There are always options, always possibilities. While it’s far less thematically ambitious than Ultima V — unlike the Ultima games, Wasteland was never intended to be anything more or less than pure escapist entertainment — Wasteland‘s more flexible, player-friendly design pointed the way forward while Ultima V was still glancing back.

Indeed, a big part of the enduring appeal of Wasteland to those who love it is the sheer number of different ways to play it. Interplay picked up on this early, and built an unusual feature into the game: it’s possible to reset the entire world to its beginning state while keeping the same group of lovingly developed characters. Characters can advance to ridiculous heights if you do this enough, taking on some equally ridiculous “ranks”: “1st Class Fargo,” “Photon Stud,” etc., culminating in the ultimate achievement of the level 183 “Supreme Jerk.” This feature lets veteran players challenge themselves by, say, trying to complete the game with just one character, and gives an out to anyone who screws up her initial character creation too badly and finds herself overmatched; she can just start over again and replay the easy bits with the same party to hopefully gain enough experience to correct their failings. It takes some of the edge off one of the game’s most obvious design flaws: it’s all but impossible to know which skills are actually useful until you’ve made your way fairly deep into the game.

The very fact that re-playing Wasteland requires you to reset its world at all points to what a huge advance it represents over the likes of The Bard’s Tale. The first CRPG I know of that has a truly, comprehensively persistent world, one in which the state of absolutely everything is saved, is 1986’s Starflight (a game that admittedly is arguably not even a CRPG at all). But that game runs on a “big” machine in 1980s terms, an IBM PC or clone with at least 256 K of memory. Wasteland does it in 64 K, rewriting every single map on the fly as you play to reflect what you’ve done there. Level half of the town of Needles with explosives early in the game, and it will still be leveled when you return many days later. Contrast with The Bard’s Tale, which remembers nothing but the state of your characters when you exit one of its dungeon levels, which lets you fight the same big boss battles over and over and over again if you like. The persistence allows you the player to really affect the world of Wasteland in big-picture ways that were well-nigh unheard-of at the time of its release, as Brian Fargo notes:

Wasteland let you do anything you wanted in any order you wanted, and you could get ripple effects that might happen one minute later or thirty minutes later, a lot like [the much later] Grand Theft Auto series. The Ultima games were open, but things tended to be very compartmentalized, they didn’t ripple out like in Wasteland.

Wasteland is a stunning piece of programming, a resounding justification for all of the faith Fargo placed in the young Alan Pavlish. Immersed in the design rather than the technical end of things as they were — which is itself a tribute to Pavlish, whose own work allowed them to be — St. Andre and Stackpole may still not fully appreciate how amazing it is that Wasteland does what it does on the hardware it does it on.

All of which rather raises the question of why I don’t enjoy actually playing Wasteland a little more then I do. I do want to be careful here in trying to separate what feel like more objective faults from my personal issues with the game. In the interest of fairness and full disclosure, let me put the latter right out there first.

Put simply, the writing of Wasteland just isn’t to my taste. I get the tone that St. Andre and Stackpole are trying to achieve: one of over-the-top comic ultra-violence, like such contemporary teenage-boy cinematic favorites as the Evil Dead films. And they do a pretty good job of hitting that mark. Your characters don’t just hit their enemies in Wasteland, they “brutalize” them. When they die, enemies “explode like a blood sausage,” are “reduced to a thin red paste,” are “spun into a dance of death,” or are “reduced to ground round.” And then there’s some of the imagery, like the blood-splattered doctor in the infirmary.

The personal appeal you find in those quotes and that image, some of the most beloved among Wasteland‘s loyal fandom, says much about whether you’ll enjoy Wasteland as a whole. In his video review of the game, Matt Barton says that “you will be disgusted or find it hilarious.” Well, I must say that my own feelings rather contradict that dichotomy. I can’t quite manage to feel disgusted or outraged at this kind of stuff, especially since, in blessed contrast to so many later games, it’s almost all described rather than illustrated. I do, however, find the entire aesthetic unfunny and boring, whether it’s found in Wasteland or Duke Nukem. In general, I just don’t find humor that’s based on transgression rather than wit to be all that humorous.

I am me, you are you, and mileages certainly vary. Still, even if we take it on its own terms it seems to me that there are other problems with the writing. As CRPG Addict Chester Bolingbroke has noted, Wasteland can’t be much bothered with consistency or coherency. The nuclear apocalypse that led to the situation your characters find themselves in is described as having taken place in 1998, only ten years on from the date of Wasteland‘s release. Yet when the writers find it convenient they litter the game with absurdly advanced technology, from human clones to telepathic mind links. And the tone of the writing veers about as well, perhaps as a result of the sheer number of designers who contributed to the game. Most of the time Wasteland is content with the comic ultra-violence of The Evil Dead, but occasionally it suddenly reaches toward a jarring epic profundity it hasn’t earned. The main storyline, which doesn’t kick in in earnest until about halfway through the game, is so silly and nonsensical that few of even the most hardcore Wasteland fans remember much about it, no matter how many times they’ve played through it.

Wasteland‘s ropey plotting may be ironic in light of Stackpole’s later career as a novelist, but it isn’t a fatal flaw in itself. Games are not the sum of their stories; many a great game has a poor or nonexistent story to tell. To whatever extent it’s a triumph, Wasteland must be a triumph of game design rather than writing, one last hurrah for Michael Stackpole the designer before Michael Stackpole the novelist took over. The story, like the stories in many or most allegedly story-driven games, is just an excuse to explore Wasteland‘s possibility space.

And that possibility space is a very impressive one, for reasons I’ve tried to explain already. Yet it’s also undone, at least a bit, by some practical implementation issues. St. Andre and Stackpole’s determination to make an elegant game design rather than an elegant program comes back to bite them here. The things going on behind the scenes in Wasteland are often kind of miraculous in the context of their time, but those things are hidden behind a clunky and inelegant interface. In my book, a truly great game should feel almost effortless to control, but Wasteland feels anything but. Virtually every task requires multiple keystrokes and the navigation of a labyrinth of menus. It’s a far cry from even the old-school simplicity of Ultima‘s alphabet soup of single-keystroke commands, much less the intuitive ease of Dungeon Master‘s mouse-driven interface.

Some of Wasteland‘s more pernicious playability issues feel like they stem from an overly literal translation of the tabletop experience to the computer. The magnificent simplicity of the Mercenaries, Spies, and Private Eyes system feels much more clunky and frustrating on the computer. As you explore the maps, you’re expected to guess where a skill and/or attribute might be of use, then to try manually invoking it. If you’re not constantly thinking on this level, and always aware of just what skills every member of your party has that might apply, it’s very easy to miss things. For example, the very first map you’re likely to visit contains a mysterious machine. You’re expected to not just dismiss that as scenery, or to assume it’s something you’ll learn more about later, but rather to use someone’s Intelligence to learn that it’s a water purifier you might be able to fix. Meanwhile other squares on other maps contain similar descriptions that are just scenery. In a tabletop game, where there is a constant active repartee between referee and players, where everything in the world can be fully “implemented” thanks to the referee’s imagination, and where every player controls just one character whom she knows intimately instead of a whole party of four, the Mercenaries, Spies, and Private Eyes system works a treat. In Wasteland, it can feel like a tedious, mechanistic process of trial and error.

Other parts of Wasteland feel like equally heroic but perhaps misguided attempts to translate things that are simple and intuitive on the tabletop but extremely difficult on the computer to the digital realm at all costs, full speed ahead and damn the torpedoes. There is, for instance, a convoluted and confusing process for splitting your party into separate groups that can be on entirely separate maps at the same time. It’s impressive in its way, and gives Wasteland claim to yet another first in CRPG history to boot, but one has to question whether the time and effort put into it might have been better spent making a cleaner, more playable computer game. Ditto the parser-based conversation engine that occasionally pops up. An obvious attempt to bring the sort of free-form conversations that are possible with a human referee to the computer, in practice it’s just a tedious game of guess-the-word that makes it far too easy to miss stuff. While I applaud the effort St. Andre and Stackpole and their colleagues at Interplay made to bring more complexity to the CRPG, the fact remains that computer games are not tabletop games, and vice versa.

And then there’s the combat. The Bard’s Tale is still lurking down at the foundation of Wasteland‘s combat engine, but Interplay did take some steps to make it more interesting. Unlike in The Bard’s Tale, the position of your party and their enemies are tracked on a graphical map during combat. In addition to the old Bard’s Tale menu of actions — “attack,” “defend,” etc. — you can move around to find cover, or for that matter charge up to some baddies and stave their heads in with your crowbars in lieu of guns.

Yet somehow combat still isn’t much fun. This groundbreaking and much beloved post-apocalyptic CRPG also serves as an ironic argument for why the vast majority of CRPG designers and players still favor fantasy settings. Something that feels important, maybe even essential, feels lost without the ability to cast spells. Not only do you lose the thrill of seeing a magic-using character level up and trying out a new slate of spells, but you also lose the strategic dimension of managing your mana reserves, a huge part of the challenge of the likes of Wizardry and The Bard’s Tale. In theory, the acquiring of ever more powerful guns and the need to manage your ammunition stores in Wasteland ought to take the place of spells and the mana reserves needed to cast them, but in practice it doesn’t quite work out like that. New guns just aren’t as interesting as new spells, especially considering that there really aren’t all that many of the former to be found in Wasteland. And you’re never very far from a store selling bullets, and you can carry so many with you anyway that it’s almost a moot point.

Most of all, there’s just too much fighting. One place where St. Andre and Stackpole regrettably didn’t depart from CRPG tradition was in their fondness for the wandering monster. Much of Wasteland is a dull slog through endless low-stakes battles with “leather jerks” and “ozoners,” an experience sadly divorced from the game’s more interesting and innovative aspects but one that ends up being at least as time-consuming.

For all these reasons, then, I’m a bit less high on Wasteland than many others. It strikes me as more historically important than a timeless classic, more interesting than playable. There’s of course no shame in that. We need games that push the envelope, and that’s something that Wasteland most assuredly did. The immense nostalgic regard in which it’s still held today says much about how amazing its innovations really were back in 1988.

As the gap between that year of Wasteland‘s release and Fargo, Pavlish, and Stackpole’s December 1985 meeting will attest, this was a game that was in development an insanely long time by the standards of the 1980s. And as you have probably guessed, it was never intended to take anything like this long. Interplay first talked publicly about the Wasteland project as early as the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June of 1986, giving the impression it might be available as early as that Christmas. Instead it took fully two more years.

Thanks to Wasteland‘s long gestation, 1987 proved a very quiet year for the usually prolific Interplay. While ports of older titles continued to appear, the company released not a single original new game that year. The Bard’s Tale III, turned over to Bill Heineman following Michael Cranford’s decision to return to university, went into development early in 1987, but like Wasteland its gestation would stretch well into 1988. (Stackpole, who was apparently starting to like this computer-game development stuff, wrote the storyline and the text for The Bard’s Tale III to accompany Heineman’s design.) Thankfully, the first two Bard’s Tale games were continuing to sell very well, making Interplay’s momentary lack of productivity less of a problem than it might otherwise have been.

Shortly before Wasteland‘s belated release, St. Andre, Stackpole, and Pavlish, along with a grab bag of the others who had worked with them, headed out to the Sonoran Desert for a photo shoot. Everyone scoured the oddities in the backs of their closets and the local leather shops for their costumes, and a professional makeup team was recruited to help turn them all into warriors straight out of Mad Max. Bill Heineman, an avid gun collector, provided much of the weaponry they carried. The final picture, featured on the inside cover of Wasteland‘s package, has since become far more iconic than the art that appeared on its front, a fitting tribute to this unique team and their unique vision.

Some of the Wasteland team. From left: Ken St. Andre, Michael Stackpole, Bill Dugan, Nishan Hossepian, Chris Christensen, Alan Pavlish, Bruce Schlickbernd.

Both Wasteland and The Bard’s Tale III were finished almost simultaneously after many months of separate labor. When Fargo informed Electronic Arts of the good news, they insisted on shipping the two overdue games within two months of each other — May of 1988 in the case of Wasteland, July in that of The Bard’s Tale III — over his strident objections. He had good grounds for concern: these two big new CRPGs were bound to appeal largely to the same group of players, and could hardly help but cannibalize one another’s sales. To Interplay, this small company that had gone so long without any new product at all, the decision felt not just unwise but downright dangerous to their future.

Fargo had been growing increasingly unhappy with Electronic Arts, feeling Interplay just wasn’t earning enough from their development contracts for the hit games they had made for their publisher. Now this move was the last straw. Wasteland and The Bard’s Tale III would be the last games Interplay would publish through Electronic Arts, as Fargo decided to carry out an idea he’d been mulling over for some time: to turn Interplay into a full-fledged publisher as well as developer, with their own name — and only their own name — on their game boxes.

Following a pattern that was already all too typical, The Bard’s Tale III — the more traditional game, the less innovative, and the sequel — became by far the better selling of the pairing. Wasteland didn’t flop, but it didn’t become an out-and-out hit either. Doubtless for this reason, neither Interplay nor Electronic Arts were willing to invest in the extensive porting to other platforms that marked the Bard’s Tale games. After the original Apple II and Commodore 64 releases, the only Wasteland port was an MS-DOS version that appeared nine months later, in March of 1989. Programmed by Interplay’s Michael Quarles, it sports modestly improved graphics and an interface that makes halfhearted use of a mouse. While most original players of Wasteland knew it in its 8-bit incarnations, it’s this version that almost everyone who has played it in the years since knows, and for good reason: it’s a far less painful experience than the vintage 8-bit one of juggling disks and waiting, waiting, waiting for all of those painstakingly detailed maps to load and save.

Wasteland‘s place in history, and in the mind of Brian Fargo, would always loom larger than its sales figures might suggest. Unfortunately, his ability to build on its legacy was immediately hampered by the split with Electronic Arts: the terms of the two companies’ contract signed all rights to the Wasteland name as well as The Bard’s Tale over to Interplay’s publisher. Thus both series, one potential and one very much ongoing, were abruptly stopped in their tracks. Electronic Arts toyed with making a Bard’s Tale IV on their own from time to time without ever seeing the idea all the way through. Oddly given the relative sales numbers, Electronic Arts did bring a sequel of sorts to Wasteland to fruition, although they didn’t go so far as to dare to put the Wasteland name on the box. Given the contents of said box, it’s not hard to guess why. Fountain of Dreams (1990) uses Michael Quarles’s MS-DOS Wasteland engine, but it’s a far less audacious affair. Slipped out with little fanfare — Electronic Arts could spot a turkey as well as anyone — it garnered poor reviews, sold poorly, and is unloved and largely forgotten today.

In the absence of rights to the Wasteland name, Fargo initially planned to leverage his development team and the tools and game engine they had spent so long creating to make more games in other settings that would play much like Wasteland but wouldn’t be actual sequels. The first of these was to have been called Meantime, and was to have been written and designed by Stackpole with the help of many of the usual Wasteland suspects. Its premise was at least as intriguing as Wasteland‘s: a game of time travel in which you’d get to meet (and sometimes battle) historical figures from Cyrano de Bergerac to P.T. Barnum, Albert Einstein to Amelia Earhart. At the Winter CES in January of 1989, Fargo said that Meantime would be out that summer: “I am personally testing the maps right now.” But it never appeared, thanks to a lot of design questions that were never quite solved and, most of all, thanks to the relentless march of technology. All of the Wasteland development tools ran on the Apple II and Commodore 64, platforms whose sales finally collapsed in 1989. Interplay tinkered with trying to move the tool chain to MS-DOS for several years, but the project finally expired from neglect. There just always seemed to be something more pressing to do.

Somewhat surprisingly given the enthusiasm with which they’d worked on Wasteland, neither St. Andre nor Stackpole remained for very long in the field of computer-game design. St. Andre returned to his librarian gig and his occasional sideline as a tabletop-RPG designer, not working on another computer game until recruited for Brian Fargo’s Wasteland 2 project many years later. Stackpole continued to take work from Interplay for the next few years, on Meantime and other projects, often working with his old Flying Buffalo and Wasteland colleague Liz Danforth. But his name too gradually disappeared from game credits in direct proportion to its appearance on the covers of more and more franchise novels. (His first such book, set in the universe of FASA’s BattleTech game, was published almost simultaneously with Wasteland and The Bard’s Tale III.)

Fargo himself never forgot the game that had always been first foremost his own passion project. He would eventually revive it, first via the “spiritual sequels” Fallout (1997) and Fallout 2 (1998), then with the belated Kickstarter-funded sequel-in-name-as-well-as-spirit Wasteland 2 (2014).

But those are stories for much later times. Wasteland was destined to stand alone for many years. And yet it wouldn’t be the only lesson 1988 brought in the perils and possibilities of bringing tabletop rules to the computer. Another, much higher profile tabletop adaptation, the result of a blockbuster licensing deal given to the most unexpected of developers, was still to come before the year was out. Next time we’ll begin to trace the story behind this third and final landmark CRPG of 1988, the biggest selling of the whole lot.

(Sources: PC Player of August 1989; Questbusters of Juy 1986, March 1988, April 1988, May 1988, July 1988, August 1988, October 1988, November 1988, January 1989, March 1989. On YouTube, Rebecca Heineman and Jennell Jaquays at the 2013 Portland Retro Gaming Expo; Matt Barton’s interview with Brian Fargo; Brian Fargo at Unity 2012. Other online sources include a Michael Stackpole article on RockPaperShotgun; Matt Barton’s interview with Rebecca Heineman on Gamasutra; GTW64’s page on Meantime.

Wasteland is available for purchase from GOG.com.)

Bill Heineman now lives as Rebecca Heineman. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. ↩

Paul Jaquays now lives as Jennell Jaquays. ↩

Interestingly, Stackpole did have one connection to Interplay, through Bard’s Tale designer Michael Cranford. Cranford sent Flying Buffalo a Tunnels & Trolls solo adventure of his own devising around 1983. Stackpole thought it showed promise, but that it wasn’t quite there yet, so he sent it back with some suggestions for improvement and a promise to look at it again if Cranford followed through on them. But he never heard another word from him; presumably it was right about this time that Cranford got busy making The Bard’s Tale. ↩

In what must be a record for footnotes of this type, I have to also note that Dan Bunten later became Danielle Bunten Berry, and lived until her death in 1998 under that name. ↩

Guerilla Toss – “Perfume”

Taylor SwiftThey just get better and better

Your all-time favorites Guerilla Toss are back at it again. Their latest LP, Eraser Stargazer, released in March, is sure to quicken the heart and penetrate the senses. One that is sure to be a classic in GTOSS’s repertoire is the completely danceable, funky-fresh, Bad Mamma Jamma of four minutes and twenty five seconds, entitled “Perfume.” Vocalist Kassie Carlson holds down the fort amongst a cacophony of sound, chanting : “It could be like, it could be like/a perfume/after an idea is/absent/You could find it, you could find it/lazily/Like an aura, like an aura/that has stayed too long.” This song is a journey, an investigation of the intangible and the video for “Perfume,” is no exception.

We begin in the woods, alone with a blinking, flashing, human-like blob. We want to know more so we follow it through trees, a pink and purple shoreline and congested, digital spaces. Sometimes the blob’s movements are fluid and graceful like a sheeted ghost, other times it seems to dance to and fro like the Michelin Man. A few questions spring to mind regarding whether or not the blob is actually two separate entities or just one constantly changing form. Are they summoning each other through some sort of pixelated vision quest or is this one evolving being beckoning us? Both? None of the above?

Will Mayo, Alex Miklowski, and LSDV (Joe Mygan and Pat Chaney, with help from Kevin Butwill) are the crack team behind this one. Like a magazine collaged, dipped in acid, and put through the shredder you’ll want to watch it a couple of times and maybe project it onto the wall and start your own interstellar dance party. Enjoy the Xena-like yodeling from the comfort of your own bedroom. Watch, listen, repeat.

Bill Orcutt releases open source audio program

Taylor Swift"I’d love to see a new generation of cheap, open digital tools that encourage freaks to code so they can spend their money on drugs instead of saving up for the latest module.” I LOVE YOU BILL ORCUTT

Cracked is a “primitive and stripped down” free application created by the former Harry Pussy guitarist and programmer

Guitarist Bill Orcutt has created an open source coding program for working with sound. Entitled Cracked, it is a "free app for Mac OS. It’s a Javascript library and live coding environment for sound making."

Orcutt is best known for his abrasive guitar playing in Miami post-hardcore group Harry Pussy and his solo and group improvisations of the last decade, but he has long pursued a parallel career as a software engineer. His interests in electronics and music first came together in 1998 with Harry Pussy’s Let's Build A Pussy, a double album exploring longform drones reissued by Editions Mego on 2012.

“Lately I've been trying to find a more personal approach for making sound on the computer,” he emails, “something that feels like a software equivalent to one of the cheap Silvertone or Kay guitars I use – something primitive and stripped down, where the inner workings are exposed and easily modifiable, and the music feels like it's being made by you rather than by the program.”

Cracked, he says, “has no traditional user interface, no buttons or knobs, just a window to code into. As you type, changes are interpreted immediately and the sound updates as you go.” A video sent to us by Orcutt shows him jamming on a MIDI pad controller in front of his computer, its screen filed with lines of code, while the speakers spew out a barrage of twisted sounds. “The code itself has a syntax that mimics the way you'd patch a modular or hook up guitar effect boxes,” he argues. “Sound flows from left to right and modules are connected from outputs to inputs. So a line of code like “__().sine().lowpass().ring().reverb().out().play();” does exactly what it looks like: creates and connects a sine oscillator to a lowpass filter to a ring modulator to a reverb to the output and then starts it all playing.”

Orcutt reports Cracked is compatible with various web platforms, and that he’s working on Linux and Windows versions of the program.

“Peter Rehberg of Editions Mego told me that laptop music stopped being interesting when the computers stopped crashing,” he says. “Cracked has yet to crash my computer, but the newness of it can feel risky and occasionally produces unexpected results. Modular synths have become ubiquitous in the 20 years since the introduction of the Eurorack and for many musicians seem to have become an unexamined default. I’d love to see a new generation of cheap, open digital tools that encourage freaks to code so they can spend their money on drugs instead of saving up for the latest module.” Freaks who like the sound of that can download the program here.

Prince's The Revolution reform for live shows

Taylor Swift;—;

Prince's best known backing band reunite and promise live performances

Prince's best known band The Revolution have reformed to play some live shows. They announced they were getting back together in a video made by members Wendy Melvoin (guitar/vocals), Lisa Coleman (keyboards/vocals), Mark 'BrownMark' Brown (bass/vocals), Robert 'Bobby Z' Rivkin (drums) and Matt 'Dr' Fink (keyboards) and shown via Brown's Facebook page.

Though the band had existed in putative form since 1979, the first album officially credited to Prince & The Revolution was 1984's Purple Rain, which featured significant input from Melvoin and Coleman in particular. Following the expansion and eventual dissolution of the band after their tour supporting 1986's Parade, Melvoin and Coleman continued to work together as a duo while their former bandmates pursued solo careers and in the case of Fink, continued to work with Prince.

Over the years there have been reunions involving various configurations of ex-members. In the late 1990s, Prince toyed with the idea of releasing the Revolution-backed album Roadhouse Garden (named after an unreleased and widely bootlegged fan favourite recorded live in 1984). In 2000 he played a Minneapolis show where he was joined by Fink, Rivkin and Brown for a version of "America". In 2012, the band – without their leader – played a benefit show at First Avenue, Minneapolis, where the live segments of the Purple Rain movie were filmed.

Watch Prince & The Revolution playing "Let's Go Crazy" live in Syracuse circa 1985:

After 13 years, 'casual' game hub JayIsGames will shut down

Taylor SwiftRIP to the site that helped me procrastinate throughout the latter half of my college education and straight through the entirety of my career :(

Katy B & Chris Lorenzo – I Wanna Be

Taylor SwiftYEs yes yes yes es yes yes yes

Cruising to victory without fuss.

[Video][Website]

[8.00]

Crystal Leww: The brand management with Katy B has always been awful throughout the entirety of her career, but it’s been particularly perplexing with Honey. Following the massive collaboration with KDA and Tinie Tempah, they went with the big brand name recognition approach and went with the Major Lazer and Craig David collaboration for the single. That could have been great, but the track was a goopy mess, and the album cycle suffered for it. She’s settled back into her underground, underdog house status here with a Chris Lorenzo collaboration. Lorenzo’s got a lot of underground credibility; he was a big house & bass ghostwriter for ten years before finally breaking out of his anonymous role a couple of years back. “I Wanna Be” is so much well-suited for Katy B. UK pop-house has been big for a couple of years, but Lorenzo’s style which is more bass-heavy is still not quite huge even though it’s probably not so hip for the underground anymore. It’s more than a fitting backdrop for Katy B, who gets to do what she does best, which is emote over a dance-forward pop production. There’s a straight line between the underrated “Broken Record” and “I Wanna Be.” For all the mainstream stories about guys stuck in the friendzone, I’m thrilled that Katy B has given a voice for the ladies who’ve felt it, too. This is gorgeous, hurt, pulsing, beautiful dance music made for corner of the room dancing and crying.

[9]

Maxwell Cavaseno: All of these dalliances like her collaborations with Ronson and Diplo have distracted us long enough: this is the realm where Katy shines. Few singers know how to craft their songs to a dance track. Chris Lorenzo’s house is rather tame, but Katy’s all stress and anxiety in her desire, edging off the softened corners. Granted, that weird pitch-shifted ‘wanna be’ sounds like the cry of some rare bird that can’t fly, but this track soars with an enviable grace.

[8]

Danilo Bortoli: Here is a quick comparison: If On A Mission is Katy B’s Rinse 02, then Honey is her very own Wired for Sound. And that says a lot, pretty much because “I Wanna Be” indicates Katy is getting back to the club and gently moving away from those once irritating ballads. For this, she enlists Chris Lorenzo, one of the most exciting producers to come around recently. Here, his approach is additive: he tries to improve what was already perfect. Which means that “I Wanna Be” is still club music about clubs — along with the realization that they sometimes can be sad, grim places. And that their music must be as nocturnal as it is supposed to be haunting. She means it literally this time around: “Don’t leave me here in the dark,” she warns. That phrase is supposed to sound like a commandment, but it comes off as a plea.

[9]

Leonel Manzanares: I loved how long it took — a full verse-chorus cycle — for Lorenzo’s signature jackin’ beat to fully appear; it showed some welcome restraint and let Katy’s moody tone and natural magnetism lead those synths. Too bad that beat didn’t really take off, leaving this 2 a.m.-appropriate house-pop ditty underwhelming. A club-banger without much of a bang.

[6]

Cassy Gress: I could just float away on all the “I wanna be”s. She says, “Don’t leave me here in the dark” and it sounds like that’s where she is.

[7]

Will Adams: “Anxiety’s a bitch,” sighs Katy, and the production agrees: An unstable chord progression, octave-leaping hook, sad piano twinkles, and pause given to a line as crushing as “You don’t know how good it is to dream of you.” The Honey singles had failed to grab me; “I Wanna Be” slaps me out of my haze. It’s the most immediate and urgent Katy B has been in a long while.

[9]

Alfred Soto: With an anonymous singer “I Wanna Be” would be a minor triumph; with Katy B it’s a new classic, the apotheosis of the Brit house revival. Her technical limitations dovetail with Chris Lorenzo’s willingness to manipulate her vocal: the title hook has echoes of Luther Vandross, Stevie B, and Spice Girls, and it’s not bunk.

[8]

Missed Classic: Impossible Mission

Taylor SwiftOne of the very finest games of my youth!!!! I really gotta go back and try to clear it.

|

| This cover makes me think of the movie Wargames |

|

| I'll have to search the bed, drawers and candy machine in this room, all while avoiding the robots |

- Blind Walker – they just travel at a constant speed along their platform, turning around when they reach the end

- Edge Shooter – similar to blind walkers, but at each platform end, they shoot electricity both before and after turning, but don't shoot unless they're at an edge

- Still Shooter – they guys just stand still and shoot, often alternating between shooting left or right, sometimes shooting constantly in one direction, occasionally starting shooting one direction then switching direction just when you think they're simple still shooters.

- Constant Follower – these robots follow the player horizontally wherever they are – they are sometimes shooters, sometimes edge shooters and sometimes not shooters.

- Constant Shooters – these are like blind walkers but stop regularly to shoot, they don't notice where the player is at all

- I See You Robots – these can be constant followers or blind walkers but when they see the player, they either immediately shoot until they lose sight of you or travel extremely fast in the direction of the player

- I'm Looking For You Robots – these guys are like blind walkers, but turn around to look behind them regularly as they travel. As soon as they see you, they either shoot or travel like the I See You variant

- Big Black Balls – these things are giant balls that act like Constant Followers, but are the only robots to travel vertically as well, following the player not just left and right, but up and down as well. They can't travel through platforms though, so can be herded with careful planning. With some good placement, these can even be directed into the path of a robot which instantly kills the Big Black Ball.

- Big Black Figure Eight Ball – this is the one variant of the Big Black Ball that, instead of following the player, travels quickly in a constant figure eight pattern, This requires careful timing but the predictability makes them easier to avoid than most robots

|

| Do any of these punch card parts match? I found this screen overwhelming before I knew what the hell I was supposed to do |

|

| Can you guess what 9-letter word the password is spelling? |

|

| For this room my tactic was to get to the top level where the bookcase is and... damn, it's a Still Shooter - need to find a robot snooze password |

|

| If you played the game back in the 80s and only remember one room, I'm guessing it's this one |

|

| You thought I was kidding about the giggling space penguins, didn't you? |

Because Why the Fuck Not?

Taylor SwiftAs the author of this Puzzle & Dragons blog gets sicker and sicker of playing Puzzle & Dragons every day, his posts get better and better.

Art Ensemble of Chicago live at the North Sea Jazz Festival 1990

Taylor SwiftThis is awesome. Download is in .FLAC.

Here's one I keep coming back to regularly. Beautifully recorded by Dutch radio, this is an excerpt of their performance at the NSJF in Scheweningen in 1990. I went to see them in 1987 and I recall they were playing up on the roof of the main concert building in Scheweningen which is just outside The Hague. I'm not sure whether this is the first set or whether it is a cut and paste of their full performance. There is a longer audience tape of the full one, but of lower audio quality. So I'm sticking with this one instead, even if shorter.

We get to hear first the serene "Prayer for Jimbo Kwesi" which was out on "The Third Decade" album. Then follows an improvisational passage, featuring Roscoe Mitchell among other exciting happenings, and after that it segues into the stately "Song for Atala" which was on their "Dreaming of the Masters", showing that the AEC can play 'em as straight as anybody. The info file that came with this set lists more than what you actually get to hear here.

The line-up is the usual quintet which you can see above. So what else to say but enjoy the company of the masters! Just possibly my fave ensemble of all and anytime!

I Dropped My Phone The Screen Cracked

Taylor SwiftIMPORTANT: Bill Orcutt wrote this audio manipulation library (sidebar: Bill Orcutt is a programmer??!?!?!?!)

Emmett Butler

Taylor SwiftEMMETT!!!!!!!!

Who are you, and what do you do?

My name is Emmett Butler. I'm a software engineer at Parse.ly where I build data collection infrastructure and maintain open source projects related to that work. I'm the maintainer of PyKafka, an open source Python client library for the Kafka distributed log processing server.

I have also built several video games, including the recently released Cibele with Nina Freeman and Star Maid Games, a game based on a true story about a young woman and a young man who meet up to have sex after forming a relationship in an online game. Other games I've worked on include How Do You Do It? and Heads Up! Hot Dogs. I'm interested in building systems and learning more about engineering.

What hardware do you use?

I do most of my programming work on a ThinkPad W530 with eight virtual cores and 8GB of RAM running Debian. When I'm doing things that are specific to Mac or Windows, I resort to my 2009 MacBook Pro with a Windows partition.

In my home office, I use a GeekDesk, a Herman Miller office chair, and an Imprint floor mat to help with standing fatigue. My keyboard is a mechanical CODE Keyboard - mechanical switches cause less typing fatigue over time, which I find to be the most important improvement over standard keyboards. Along the same lines, I've got a thumb-controlled trackball instead of a standard mouse, and a single large monitor that I use instead of the laptop's screen.

And what software?

I love Debian-flavored Linux, and I've been running either Ubuntu or Debian since 2010. Python is currently my language of choice, and I constantly make use of the huge array of open source libraries and tools available to Python programmers.

Apache's Storm and Kafka projects are two of the cornerstones of the platform that Parse.ly is building, and I write code that talks to them quite regularly. When coding, I use a native vim client - gvim on Linux/Windows, MacVim on Mac. For a while, I was using Sublime Text's vim compatibility mode, and it eventually got too cumbersome so I just started using vim. I like the speed at which I can translate thoughts into code in vim compared to other tools, though becoming proficient in vim does require a bit of concerted effort. Practical Vim is a great resource for anyone interested in learning more about efficient code editor use.

I love tmux as a cross-platform way to script common terminal use cases - I have a tmux script that starts a ZooKeeper server and three Kafka client brokers all running in foreground terminals, for example. I've experimented with xterm and Terminator as alternate terminal emulators, but I've found the Mac and Debian defaults to be the best for my needs. On Windows, though, I use the ConEmu console emulator instead of the horrendous default terminal.

What would be your dream setup?

I'm actually pretty close to having my dream setup right now. I suppose it would also involve a door that closes - my current home office is in a corner of our two-room apartment's main room. Other than that, some lower back supports on my chair would be nice. I've put a lot of thought into minimizing my physical discomfort during the work day, and that's probably the biggest hole left in the arrangement.

Thanks for reading! If you're enjoying the interviews, you can help keep this nerdy lil' site independent for as little as $1 a month!

Nintendo Ultra Hand box from 1973

Recently I was lucky to find a Nintendo Ultra Hand in the box version from the early 1970s. This had been on my wanted list for a long time. Although the one I found wasn't in perfect condition, these are so rare that I happily added it to my collection.

|

| Nintendo Ultra Hand (1973 box version) |

I had been on the lookout for more than fifteen years for this version, after first seeing a tiny picture of it online. As I could not find it in any vintage toy shop in Japan, nor on any auction site, I was beginning to wonder if it really existed.

|

| Nintendo leaflet from November 1973 (front) |

This box version was also featured in a 1973 Nintendo leaflet that shows the toy range that Nintendo sold in the early 1970s.

|

| Nintendo leaflet from November 1973 (back) |

On the back of this leaflet the Ultra Hand was shown in a new box design, next to other toys from that era like the Mach Rider and Ele-Conga.

The Ultra Hand was first introduced in 1966 and became Nintendo's first million seller. Seven years later this sales boom was long over, but Nintendo must have still believed in this product, or had surplus stock, when they introduced a new box design. As it was well past its hype days, it must have sold in small numbers at that time. Which would explain why it is so hard to track down in this version.

Read more... »

Morning Makeup Madness (Jenny Jiao Hsia)

"It draws from my personal experiences of waking up late in the morning and having very little time to get ready." - Author's description

Play on itch.io (Browser)

Michael Brough heading back to App Store with latest roguelike, Imbroglio

Taylor SwiftOh fuck yes

Around the halls of Mt. Hexmap, Michael Brough is best known as the creator of one of Owen's favorite games 868-HACK. It was a roguelike whose simple premise belied its depth and is a game everyone should have in their Purchased history. He's made some other games since then (2014's Helix comes to mind) but coming soon is Brough's latest, another roguelike entitled Imbroglio.

Imbroglio on the surface looks a lot like 868-HACK. Each level fits on one screen, although Imbroglio is only 4x4 as opposed to 868's 6x6. There's one major difference, however, and that's deckbuilding. Not the Ascension type, but more like Magic: The Gathering where you'll craft a deck that you'll carry with you on each run. Thus, you'll choose your weapons and such by building a deck and then head into the dungeon, experience permadeath, rebuild deck a deck and try again. Imbroglio has multiple characters each with unique cards that you can mix and match, so building combos and using different characters will make each run feel different.

We don't have an ETA on Imbroglio yet, but it should be soon. We know it's been submitted to Apple, so hopefully it's in our hands within the next week or two. We'll fill you in as soon as it goes live.

Milk scheme

I used to have an idea for a ‘milk scheme’. The milk scheme involved me, every morning before college, going into the Sainsburys next to the bus station, and buying exactly four of the hefty, four-litre bottles of whole milk. And then when I was buying the milk, every day, I would say to the person at the check-out, “always good to start the day with a cold glass of milk.” And then I would pack the bottles into my school bag, all except for one of them, which I would unscrew the top off and start drinking from, deeply and hungrily, and it would go all down my chin.

“Always good to start the day with a cold glass of milk.” I would start out saying this very cheerily, like I was genuinely enjoying the milk, and it was having on me all these beneficial, health-giving effects. But then over time, after weeks and months of doing this, after all the staff there had become familiarised with me as the “milk guy”, I would start to look tireder, sicker, more exhausted. I would step up to the checkout with one of the bottles already mostly empty, and milk stains all the way down my front. I would become pale and bloated with the milk. I like to imagine that my skin would have started oozing with it. For some reason I imagine that it would have taken on a purple hue.

But still, I would always greet them with, “always good to start the day with a cold glass of milk.” A little milk-sick would escape from my mouth. I would stagger away from the checkout, drinking now from a fresh bottle of milk, covered in it.

And then one day I would just stop. I would stop going in and buying the milk, and they would think I had drunk myself to death, on milk.

…

I never actually did the milk scheme, never even tried to put it into action. But when I was about 18 or so, I thought about doing it a lot.

I don’t know what this means.

I guess I want to know, in a way, how far I could have pushed myself with it.

Remembering The Time Somebody Ordered Too Few Copies Of ‘Purple Rain’ (And Way Too Many Of ‘Victory’)

Taylor SwiftGreat anecdote from Matador's Gerard Cosloy, but stick around for the fake Springsteen video

In the summer of 1984, I was employed as clerk/bag security schmoe at the Copley Square location of Strawberries Records and Tapes, the New England chain store owned by Morris Levy (who may or may not have been the inspiration for “The Sopranos” Herman “Hesh” Rabkin). This was a pretty wild time for the music business with a plethora of blockbuster albums by veteran acts competing for shelf space. In the wake of Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’, industry expectations were sky-high for The Jacksons’ ‘Victory’, to say nothing of Bruce Springsteen’s hotly anticipated ‘Born In The U.S.A.’. But both would ultimately be overshadowed (in the aisles of that Strawberries, anyway) by Prince’s 6th album, ‘Purple Rain’.

The store’s buyer loaded up on ‘Victory’ LP’s to an insane degree. THOUSANDS of the fuckers, overstock crammed into every available corner of the store’s back rooms and behind countertops. As you may or may not remember, the album was poorly received, the subsequent stadium tour (co-promoted by New England Patriots exec/heir Chuck Sullivan) bombed and well, the staff of Strawberries had boxes of ‘Victory’ hanging over their shoulders all summer long.

‘Born In The U.S.A.’, was of course, another story. Huge critical acclaim, immensely popular videos (even if the Boss was pissing on the flag, see above), and most importatly, the store had enough stock to satisfy demand, but just barely.

‘Purple Rain’, however is where things got crazy. The film wouldn’t open until late July but the album dropped in June, weeks after “When Does Cry” had pretty much blown everyone away. Despite the fact we had real-live-human beings walking into the store several times a day asking when ‘Purple Rain’ would be out (amongst them, the J.Geils Band’s Peter Wolf, who lived across the street) our store’s manager, for reasons known only to herself, determined that Prince Rogers Nelson was some product of hype and a couple hundred copies of the year’s most eagerly awaited album would be enough.

We blasted thru the available stock within a couple of hours of the doors being unlocked. Customers were outraged, apoplectic that the record they already knew would be the soundtrack to their summer wasn’t available.

An edict came down to tell aggrieved consumers that while we were out of stock on ‘Purple Rain’, we could, however, furnish them with copies of Newcleus’ ‘Jam On Revenge’, which just so happened to be released by the Morris Levy-owned Sunnyview Records.

This suggestion did not sit well with inconvenienced Prince fans. I’d previously not been cursed at in the store before, save for the time Monoman came in to yell at me about a middling review for The Lyres’ ‘On Fyre’ in Matter Magazine (“you should be in prison,” Jeff said…and he was right!). Let’s just say this was my one and only experience being on the retailer end of the Great American Bait & Switch and either I wasn’t very good at it…or Newcleus were way, way out of their league. Maybe a little of both.

So there you go. The music business when it still existed. Needless to say, ‘Purple Rain’ was great, some of us saw the movie twenty times or more and that was the summer Prince went from merely being super popular to the sort of megastardom that caused geniune panic & anxiety in Copley Square.

Richard Lyons, RIP

Prince isn’t the only great musician to die today. Richard Lyons of the legendary cult band Negativland, RIP.

Freak City, Dog Harajuku & Moschino Street Fashion in Tokyo

Shoushi (aka Shoshipoyo) is a Japanese fashion student with blue pastel hair who we often see around the streets of Harajuku.

His look here features a pink “FUBU & Versace” print top and pants from Freak City, a Dog Harajuku M&M’s bomber jacket, platform Nike sneakers from Dog Harajuku, and a Moschino cow print bag. Accessories include a lighter holder necklace by Nasir Mazhar, a KTZ beret, and Too Much Harajuku sunglasses.

Shoushi’s current favorite brand is Moschino and he likes the music of Judy and Mary. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram!

Click on any photo to enlarge it.

Scan of Alan George's Treasure Hunt

Taylor SwiftA BRAIN TONIC!

Rikarin in Harajuku w/ Colorful Leg Warmers, Cow Print & 6%DOKIDOKI

Taylor SwiftDope

Rikarin is a 19-year-old student who we often see on the street in Harajuku. She also has her own YouTube series “My Harajuku Life“.

This time, she was wearing a resale cow print plush top with shorts from 6%DOKIDOKI. She’s also wearing a backpack and waist bag from Kiki2 Koenji and Kinji Harajuku. Her pastel shoes with stars are from Yosuke, worn with handmade faux fur leg warmers, a faux fur hat, and other kawaii accessories from 6%DOKIDOKI and the 100 yen shop.

Rikarin’s favorite place to shop is 6%DOKIDOKI and her favorite band is Dempagumi.inc. Follow her on Instagram or Twitter for daily updates.

Click on any photo to enlarge it.

Mitski – Your Best American Girl

Taylor SwiftOhhhhhh this is fucking great

That would be Felicity, right?

[Video][Website]

[6.60]

Jonathan Bogart: God, I miss 1993.

[7]

Juana Giaimo: If a good single is one that has the potential to appeal audiences, then it seems that Mitski and her label had everything wrong. “Your Best American Girl” is noisy, has nearly unintelligible vocals and although it’s three minutes and a half long, it leaves an unfinished feeling. You’d expect that the chorus would maybe become epic, that she would scream one important line or that violins would transform it into a celestial song. But nothing like that happens. Instead, it finishes as quietly as it began. However, for that reason, the explosion of the chorus works as a revelation of secret emotions. As listeners, we are drawn to it and we want to hear it again, and every time it happens, it has the same striking effect it had the first time, because this could be our own secret, too.

[7]