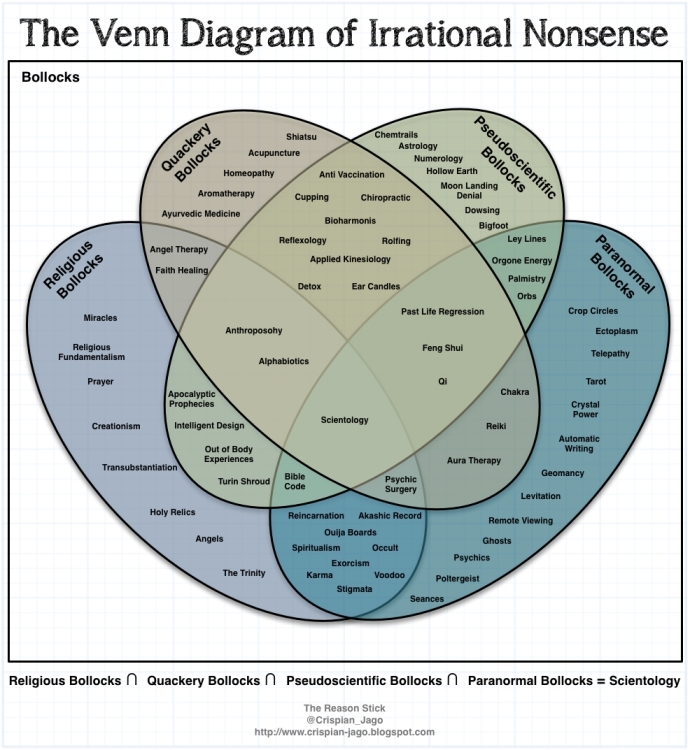

One way to describe our overall editorial stance at SBM is that we are criticizing medical science in a constructive way because we would like to see higher standards more generally applied. Science is complex, medical science especially so because it deals with people who are complex and unique. Getting it right is hard and so we need to take a very careful and thoughtful approach. There are countless ways to get it wrong.

One way to get it wrong is to put too much faith in a new technology or scientific approach when there has not been enough time to adequately validate that approach. It’s tempting to think that the new idea or technology is going to revolutionize science or medicine, but history has taught us to be cautious. For instance, antioxidants, it turns out, are not going to cure a long list of diseases.

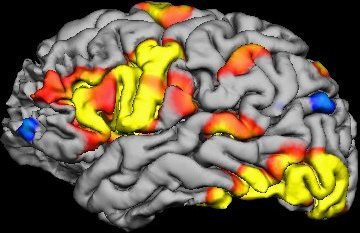

One recent technology that is very exciting, but insiders recognize is very problematic, is perhaps even more problematic than we thought –functional MRI scans (fMRI). A new study suggests that the statistical software used to analyse the raw data from fMRIs might be significantly flawed, producing a flood of false positive results.

An fMRI primer

MRI scanning uses powerful magnets to image soft tissue in the body. The magnets (1.5-3 Tesla, typically) align the spin of hydrogen atoms in water molecules with the magnetic field. The time it takes for the atoms to align and then relax depends on the characteristics of the tissue. The MRI scan therefore sees subtle differences in tissue (density, water content) and uses this information to construct detailed images.

Functional MRI takes it one step further – it images blood flow using a technique known as blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) imaging. When a part of the brain is active there is an initial dip in blood oxygenation as the neurons consume oxygen, but then blood flow increases bringing more oxygen to the tissue. This peaks at about 6 seconds, then the oxygen level dips below baseline and then back to baseline.

Software analyses the raw data from fMRI scan to create what are called voxels. A voxel is a three-dimensional pixel, representing a tiny cube of brain tissue containing about a million cells. The software determines the activity level of each voxel based upon how closely changes in oxygenation level match the expected pattern that occurs when brain cells are active.

The software will also look for groups of voxels that have the same activity level, a phenomenon known as clustering. Scientists infer from a clustering of voxels showing increased activity which in turn is inferred from how closely it matches the expected pattern of oxygenation, that a part of the brain is undergoing increased activity. Researchers try to correlate such regional activity with specific tasks, and then infer that this part of the brain is involved in that task.

The Black Box

Already we can see that interpreting the results of an fMRI study involves a chain of inference. The chain gets longer, however, because often researchers will need to do multiple trials of multiple individuals and then compare their brain activity statistically.

For example, you might have one control group that is essentially doing nothing, while another group is looking at a specific image. Then you compare the fMRI activity statistically between the two groups, and can conclude that looking at the specific image correlates with increased activity in one part of the brain, and from that you infer that the active part of the brain is involved in visual processing.

To date about 40,000 such studies have been published, adding a tremendous amount to our knowledge of what different parts of the brain are doing and how they connect up and interact.

However, in addition to other problems with fMRI studies, a key link in this long chain of inference has always been a bit of a controversy – the statistical analysis of the raw data to detect clusters of voxels that are active together. Researchers use statistical software packages that they purchase. They need to learn how to use the software, but most neuroscientists are not software engineers and so they have to trust that the software works as advertised. To them the software is a black box that spits out data.

Famously, neuroscientist Craig Bennett scanned a dead salmon using fMRI and found that when the dead salmon was shown pictures, the software detected a statistical cluster of voxel activity in its brain. Bennett won an Ig Nobel prize for his efforts. More importantly, he sounded an alarm bell that fMRI software might have a problem with generating false positives.

The new study

“Cluster failure: Why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates,” was recently published in PNAS by authors Anders Eklund, Thomas E. Nichols, and Hans Knutsson. This is a follow up study to earlier work with similar results.

In their prior study they set out to conduct validation tests of one popular fMRI statistical software package. They used existing open source data for task-based in individual data, using a null data set (meaning there should be no difference). Given where the thresholds are set in terms of finding a statistical match to a pattern of oxygenation consistent with brain activity, there should be a 5% false positive rate. They found a false positive rate as high as 70%.

The current study expands on their earlier work. First, they are using three of the most common statistical software packages instead of just one, and they are also comparing groups rather than just individuals. They compare two groups each randomly drawn from the same pool of healthy individuals, so there should be no difference. Again, there should be a 5% false positive rate, but they found many statistical tests with much higher false positive rates, between 60-90%. (This depends on the parameters used, like number of subjects and threshold of statistical significance.) They summarize these results:

For a nominal familywise error rate of 5%, the parametric statistical methods are shown to be conservative for voxelwise inference and invalid for clusterwise inference.

There is a lot of statistical jargon in the paper, but basically the voxelwise inference tended to be conservative and have a valid false positive rate less than 5%, while the clusterwise inference tended to have high levels of false positive.

The authors also make two other important points. The first is that they corrected statistically for multiple comparisons when doing their analyses. (In other words, if you roll the dice 20 times, you are likely to get a 5% result once, so you have to adjust the statistical thresholds to account for the fact that you rolled 20 times.) However, in their review of published papers 40% do not correct for multiple comparisons. This means, in those 40% of papers, false positive rates are likely to be even higher.

They also complain that many researchers did not store their raw data in a way that would allow for a reanalysis of the data. We only have the results of the statistical analysis, but cannot run the analysis again with better methods or thresholds.

They also note that a specific software bug was discovered:

Second, a 15-year-old bug was found in 3dClustSim while testing the three software packages (the bug was fixed by the AFNI group as of May 2015, during preparation of this manuscript). The bug essentially reduced the size of the image searched for clusters, underestimating the severity of the multiplicity correction and overestimating significance (i.e., 3dClustSim FWE P values were too low).

What’s the fix?

This type of research is critical to the practice of science – it’s what makes science self-corrective. It also has to do directly with a concept that is critical to science but underappreciated, especially in the general public, that of validity.

Any test or measurement has to be validated, which usually means that the test is used with known data to see that it produces the results it should, that those results are meaningful, and that they are precise and reliable. Until a test has been validated, you don’t know what the results actually mean. They are like the personality tests given is Cosmopolitan Magazine; for entertainment purposes only.

What the authors of the current study are essentially saying is that the statistical software used to tease a signal out of the massive amount of noise generated by fMRI scans have not been properly validated. Prior validation studies were inadequate. Their studies are a better validation paradigm, and they show significant problems with the software that cause at least these three popular packages to generate high percentages of false positives.

The authors conclude:

It is not feasible to redo 40,000 fMRI studies, and lamentable archiving and data-sharing practices mean most could not be reanalyzed either. Considering that it is now possible to evaluate common statistical methods using real fMRI data, the fMRI community should, in our opinion, focus on validation of existing methods.

In other words, we have to dust ourselves off and just move forward. Let’s fix the statistical problems and make sure that fMRI studies going forward are more valid.

I have already had a skeptical eye toward fMRI research given all the crazy results that have been published (the dead salmon study aside). Now I am even more skeptical. Some of the research is clearly very rigorous and high quality, but much of it had many red flags for false positive results (sloppy methods, lack of replication, implausible results).

Hopefully this research and similar validation research will tighten up the field of fMRI research. It is an incredibly powerful tool, but it is tricky to use.