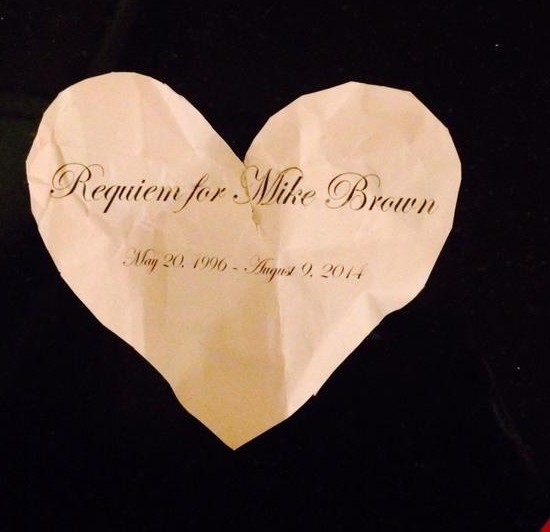

Via the Saint Louis Dispatch

“Michael Brown protesters interrupted the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra’s concert on Saturday night, causing a brief delay in the performance at Powell Symphony Hall.

The orchestra and chorus were preparing to perform Johannes Brahms’ Requiem just after intermission when two audience members in the middle aisle on the main floor began singing an old civil rights tune, “Which Side are You on?” They soon were joined, in harmony, by other protesters, who stood at seats in various locations on the main floor and in the balcony.

The protesters then unfurled three hand-painted banners and hung them from the Dress Circle boxes. One banner listed the birth and death date of Brown, who was shot by Ferguson police Officer Darren Wilson on Aug. 9.

The five-minute interruption was met with a smattering of applause from some audience members, as well as members of the orchestra and chorus. Others simply watched as the orchestra remained silent.”

I wasn’t there, obviously, but I’m inclined to say the protesters did the right thing- certainly that their actions, to me, seem both justified and appropriate.

There have been many political protests at the Proms over the years, some poignant and effective, some simply disgraceful. It all has to do with motivation for the protest, respect for the audience, appropriateness of context and respect for the music. Interrupting the piece would have been disrespectful to music, musicians and audience. Protesting before a Requiem seems poignant and appropriate- someone ought to be singing in memory of any and all people killed by violence. Maybe the protest helped people hear the work with more open ears and raw nerves- probably upsetting, but eye opening. One friend of mine questioned whether staging a protest on private property was fair to the hall, the orchestra and the audience. I’m not sure I agree. If the concert hall can’t be the center of civic life, a hub for intellectual discussion, a place to share ideas, a place we can mourn, cry, scream, love and heal together, we may as well burn every concert hall to the ground. When we value genteel niceties and professional convenience over the existential questions of right and wrong, life and death, we, as artists, have probably made ourselves completely irrelevant.

Classical music was once the most political of art forms. Beethoven wrote the Eroica in support of Napoleon’s struggles for liberty and freedom from an oppressive monarchy. When Bonaparte crowned himself emperor, Beethoven famously scratched out the dedication to the fallen hero. Wagner may have been a toxic soul, but he was deeply engaged in political ideas and clearly saw his music as, among other things, an instrument of social and political change. Sibelius’s music helped fuel the Finnish struggle for liberation from Russian occupation, and Verdi’s helped bring together Italy into a modern and united country. Mozart’s three great operas based on libretti by Lorenzo Da Ponte were provocative and highly controversial political statements questioning the birthright of the ruling class, the inherent nobility of the noble, and the wisdom and decency of those who rule. Benjamin Britten’s masterpiece, the War Requiem, is a pacifist cris de coeur, that not only reminds us of the utter futility of industrial scale mass murder, but also of the fundamental humanity of those on both sides of any conflict. Shostakovich described much of his music as a gallery of tombstones- memorials to victims of Stalinist terrors and Nazi atrocities. Rostropovich’s performance of the Dvorak Cello Concerto during the 1968 Russian crushing of the Prague Spring remains one of the musical and social high-points of Proms history. I could go on.

It has been a widely accepted truism in my lifetime that music and politics ought to be kept separate. There is a kernel of wisdom in this idea. Music ought to bring us together, not drive us apart, and I know that by keeping my political ideals out of the discussion to the best of my ability in the workplace, I’ve been able to form countless friendships and vital collaborations with people who have very different political outlooks and world-views from me. The social act of making and sharing music has provided a framework and a forum for me, and them I hope, to find common ground. It’s important we nurture that fragile shared public space.

On the other hand, if we can’t agree on the rightness and wrongness of certain things, what is the point of that public space? If we can’t find some common ground in our understanding of massive historical events and social problems, what hope to we have of improving the human condition? How perfect is it that the protesters sang “Which Side are You on?” I read that as referring to the side of life or the side of death, the side of love or the side of hate, the side of peace or the side of murder. Too many people seem to be seeing it terms of the side of white people or the side of black people, the side of the cops or the side of Mike Brown. Simply agreeing on the pleasant sound made by a fine orchestra and chorus performing Brahms is not enough. Classical music, worried about alienating funders and scaring off audience, has completely neutered itself in my lifetime. Politics is a combative business- a rough and imprecise way of working through the problems society faces. All too often, in order to appear reasonable and unbiased, our social discourse offers equal time to both right and wrong. Art can help us to illuminate and clarify what is right and what is wrong by engaging and awakening our sense of empathy. Which Side are You on? We hope you’re on the side of empathy.

We call a Requiem a “Mass for the Dead” but that’s a misleading bit of shorthand. It’s better thought of as a “Mass of Remembrance for the Survivors” (my teacher, Gerhard Samuel, wrote an important work called “Requiem for Survivors” that explores this very idea). A Requiem exists to give voice to the pain of loss and to help us find reason and comfort in our darkest hours. The media belittles and trivializes human life at every turn. If this week’s protest helped anyone to listen to Brahms’s music with more empathy, to think about the value of Mike Brown’s life and the loss being endured by his family, I think that’s a positive thing. If the performance that followed the protest could have given some solace to Mr Brown’s family or the survivors of any of the many violent deaths plaguing our society, that would have been a wonderful thing. If we can’t agree that killing is wrong, that violent deaths are always a tragedy, what hope do we have? If the words of Brahms’ Requiem are simply a framework for some beautiful music that let’s the performers show how accomplished they are and let the audience relax after a busy week, I don’t know why we’d bother struggling on to raise money to put on concerts. This is supposed to be life or death stuff- infinitely raw and relevant.

“You now have sorrow;

but I shall see you again

and your heart shall rejoice

and your joy no one shall take from you.

Behold me:

I have had for a little time toil and torment,

and now have found great consolation.

I will console you,

as one is consoled by his mother”

Original Source