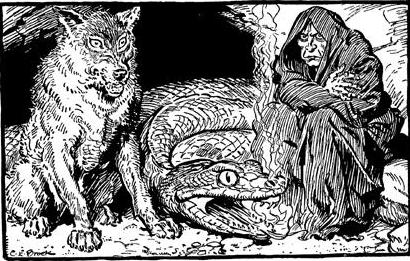

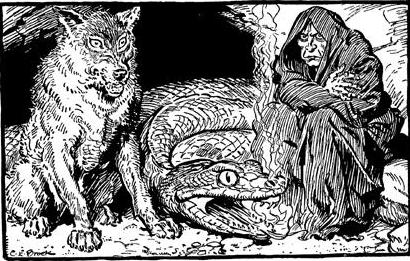

No overview of Viking mythology would be complete without delving a little bit into Loki and the role he plays in the Norse universe. Along with Odin, he’s the most mysterious and perplexing of the gods. Part of the confusion is that his physical being is difficult to nail down. He’s the son of a giant and an unknown figure — perhaps a giantess, a goddess, or something else completely. Loki is at times human-ish (like the other gods), at times a shapeshifter (like Odin), and even one time a mother — he in fact birthed Sleipnir, Odin’s eight-legged flying horse. He was indeed a father as well, but his offspring were terrifying beings like Jormungand (the world-encircling serpent), Fenrir (the great wolf), and Hel (the goddess of the underworld). Before even getting into his character traits, it’s obvious that Loki is capricious and hard to trust.

The children of Loki: Fenrir, Jormungand, and Hel.

In terms of behavior, he’s seemingly either playfully mischievous or downright evil, depending on the story. A reader of Norse mythology is often left perplexed by Loki’s actions, and how those actions are viewed by his fellow gods. He’s cunning, but charismatic to a degree, and it’s a bit of mystery why the other gods in Asgard even keep him around.

Although he’s ever present in the Norse world, he’s never actually worshipped by Viking people like the other gods are. Additionally, while he has a role in many myths — you’ll have noticed his role in nearly all of them throughout this series — he’s never the hero. He’s simply a sideshow — either a foe or a friend, helping or hurting or instigating from the sidelines.

Let’s briefly look at the one story in which he does star, but as you’ll see, is clearly not the hero.

***

Baldur was one of Odin’s sons, known to be generous and courageous. When he started having dreams about a terrible event befalling him, his father — the wise chief — was charged with inspecting the meaning behind these foreshadowings.

So Odin ventured to the underworld, where, after consulting a seeress, he learned that Baldur was indeed doomed and destined to an early death.

Frigg, Baldur’s mother, was obviously distraught by this news. So she obtained oaths from everything in the universe to not harm her son. The gods even tested it by throwing great rocks and sticks his way, only to see the projectiles bounce off him and fall harmlessly to the ground.

Loki, of course, saw an opportunity for trickery. “Did all things swear oaths to spare Baldur from harm?” he asked Frigg. “Oh, yes,” she replied, “everything except the mistletoe. But the mistletoe is so small and innocent a thing that I felt it superfluous to ask it for an oath. What harm could it do to my son?”

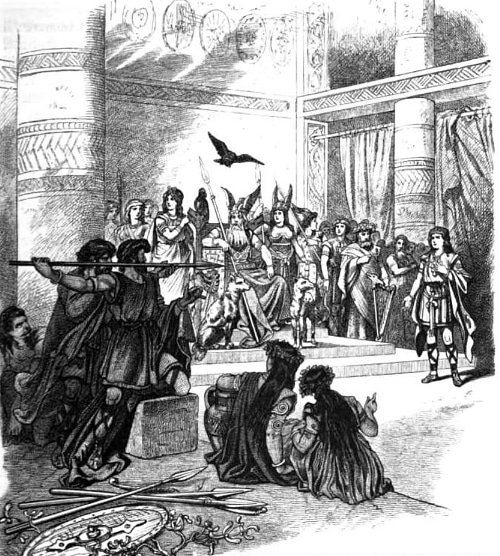

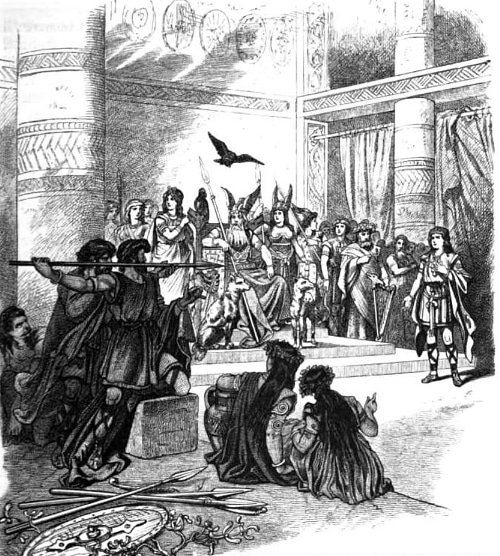

Loki then went out and found some mistletoe to bring back to Asgard. He approached the god Hodr, who was blind, and convinced him to take a spear and throw it at Baldur as yet another test of his invincibility. Indeed, the spear was crafted from mistletoe. Hodr threw the shaft, which pierced Baldur and killed him on the spot.

Loki then went out and found some mistletoe to bring back to Asgard. He approached the god Hodr, who was blind, and convinced him to take a spear and throw it at Baldur as yet another test of his invincibility. Indeed, the spear was crafted from mistletoe. Hodr threw the shaft, which pierced Baldur and killed him on the spot.

After Baldur was killed, another god, Hermod, rode to the underworld to try to convince the goddess Hel to release Baldur back to Asgard because he was so universally loved. Hel agreed that if every creature in the world wept for Baldur, she would release him. And every living thing did indeed weep for the fallen god — except one. A giantess named Tokk — certainly Loki in disguise — withheld her sorrow, and Baldur remained in the underworld.

***

This tale begs the question of where Loki fits into the Norse pantheon. Why is he there at all? What role does he play, and what can we learn from him?

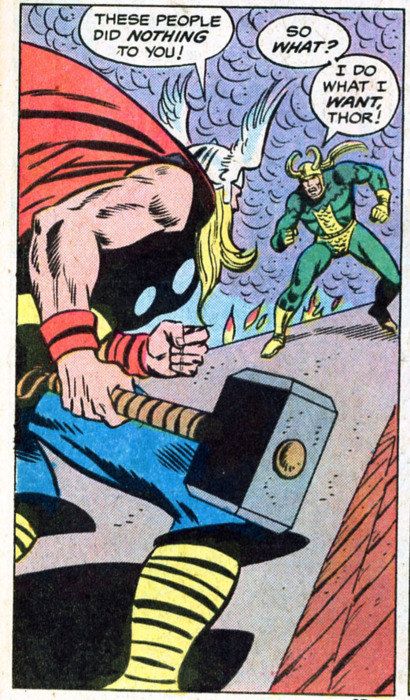

While it’s an oft-debated question, my own research seems to place him as a devil-like character. It’s not the horned, red-skinned Satan you’re probably imagining, though. Early Christianity saw the devil as more of a trickster, a being who constantly lies and deceives by subtle measures rather than through overt evil. Loki’s most common pranks are small and seemingly innocuous actions, but frequently lead to terrible consequences.

When the Vikings started to convert to Christianity near the end of their reign, they combined their pagan gods with their new religion. The character of Loki made an easy parallel to Satan. In paintings, especially as the myths aged into the centuries of the 1000s, he became a jester-type figure, another image that was also often given to the Christian devil.

In this regard Loki exemplifies the trickster archetype that’s been present in mythology and folklore for thousands of years and around the world. Portrayed as a wise fool, this ubiquitous character is most often male, is usually cunning and sometimes even playful, and generally spreads discord through pranks and deception. Sometimes the trickster is simply used for lighthearted entertainment (like Bugs Bunny), and other times — as in Loki’s case — is more of a malicious being.

His presence is often seen as a way to get people to think and behave differently — to not just flow along with the status quo and accept things at face value. The trickster is proof that deception exists in our world; sometimes it’s playful, oftentimes it’s destructive.

One thing is for sure (and some experts note this is how the Vikings looked at him): Loki embodies all that man should not be. He is unreliable, disloyal, shallow, vain, hedonistic…a laundry list of negative characteristics. He’s also incredibly profane — life was simply a joke to him; there was nothing sacred about the world he lived in. To the gods who were worshipped, and to the people worshipping them, all of life was sacred. Thor was present in the thunderstorms, Odin took flight as a raven and used other creatures as his watchdogs — Norse mythology is full of examples of the blending of the natural world and the world of the gods.

As a modern writer notes, the Viking people felt that “one embodies Loki whenever one lives in a totally profane manner, without any reference to sacred models — hence Loki’s utter lack of any allegiances to the gods, giants, or anyone else.”

Rather than being flat and one-dimensional, life can be imbued with beauty and mystery when viewed through a lens that says everything is sacred. We are loyal to those around us, because they have meaning in the world, just as we do. We are not hedonistic, because there’s more to life than what can be seen on a screen or on a plate in front of us. No matter your religion or lack thereof, you can treat every day with a certain sacredness that gives texture to an otherwise bleak existence.

And perhaps this is why Loki was kept around in the Norse pantheon. Men need examples not only of the good and honorable and moral, but also of the anti-man. It’s why we have lessons in unmanliness on the website — we can learn just as much from anti-examples as we can from the good examples. When you read the myths of the Vikings, you get a sour taste in your mouth from Loki. You learn from him in a via negativa-type way — you look at his characteristics and subtract them from your life. He’s a deceptive liar, so you should be honest and forthcoming in your interactions with people. He’s unreliable, so you should strive to be a bastion of reliability. His character is as moveable as sand, so be sure your moral foundation is as solid as rock.

To some, the word “trickster” denotes something light and playful — like a young boy pulling a prank. Over the course of writing this series, I’ve talked to numerous people about Norse mythology, and Loki is inevitably one of the characters they’re familiar with. Rather than being sinister, however, they view him in that innocent regard — fun, playful, and a prankster no doubt, but causing no real harm.

Yet I would argue that he should in fact be viewed through a more serious lens. His individual acts of mischief may be small at the outset, but reap consequences far greater than what could have been foretold. Loki brought mistletoe to Asgard, and one of the beloved gods died. You sent a single flirty text to a co-worker, and it ultimately led to the end of your marriage. Small and seemingly innocent acts of deception can snowball into ruinous avalanches.

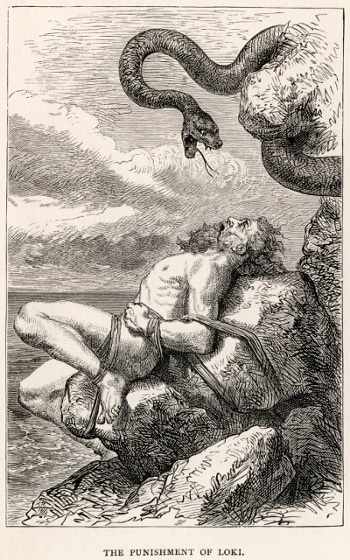

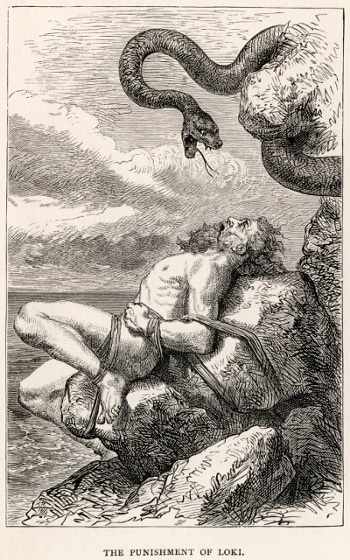

Even the gods eventually got sick of Loki’s trickery and he got what was coming to him. After Baldur’s death, and continued mocking of the other gods, he was bound to a rock with entrails and condemned to have a snake drip poison on his face forever after. He would not be unbound until Ragnarok — and to that apocalyptic event is where we will turn next time to conclude this series.

Read the rest of the Norse mythology series:

Odin

Thor

Tyr

Loki then went out and found some mistletoe to bring back to Asgard. He approached the god Hodr, who was blind, and convinced him to take a spear and throw it at Baldur as yet another test of his invincibility. Indeed, the spear was crafted from mistletoe. Hodr threw the shaft, which pierced Baldur and killed him on the spot.

Loki then went out and found some mistletoe to bring back to Asgard. He approached the god Hodr, who was blind, and convinced him to take a spear and throw it at Baldur as yet another test of his invincibility. Indeed, the spear was crafted from mistletoe. Hodr threw the shaft, which pierced Baldur and killed him on the spot.