| Piled Higher & Deeper by Jorge Cham |

www.phdcomics.com

|

|

|

||

|

title:

"A Grammatical Conundrum" - originally published

8/7/2015

For the latest news in PHD Comics, CLICK HERE! |

||

Jon Back

Shared posts

08/07/15 PHD comic: 'A Grammatical Conundrum'

09/16/15 PHD comic: 'Optimal Number of References'

| Piled Higher & Deeper by Jorge Cham |

www.phdcomics.com

|

|

|

||

|

title:

"Optimal Number of References" - originally published

9/16/2015

For the latest news in PHD Comics, CLICK HERE! |

||

09/23/15 PHD comic: 'A Universal Reference Law'

| Piled Higher & Deeper by Jorge Cham |

www.phdcomics.com

|

|

|

||

|

title:

"A Universal Reference Law" - originally published

9/23/2015

For the latest news in PHD Comics, CLICK HERE! |

||

09/26/14 PHD comic: 'Nothing'

| Piled Higher & Deeper by Jorge Cham |

www.phdcomics.com

|

|

|

||

|

title:

"Nothing" - originally published

9/26/2014

For the latest news in PHD Comics, CLICK HERE! |

||

Dependence Day: The Power and Peril of Third-Party Solutions

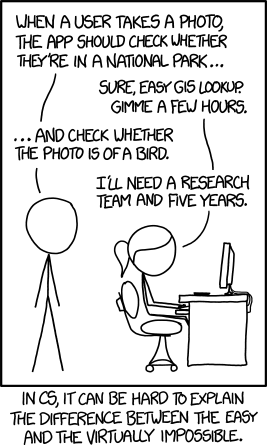

“Why don’t we just use this plugin?” That’s a question I started hearing a lot in the heady days of the 2000s, when open-source CMSes were becoming really popular. We asked it optimistically, full of hope about the myriad solutions only a download away. As the years passed, we gained trustworthy libraries and powerful communities, but the graveyard of crufty code and abandoned services grew deep. Many solutions were easy to install, but difficult to debug. Some providers were eager to sell, but loath to support.

Years later, we’re still asking that same question—only now we’re less optimistic and even more dependent, and I’m scared to engage with anyone smart enough to build something I can’t. The emerging challenge for today’s dev shop is knowing how to take control of third-party relationships—and when to avoid them. I’ll show you my approach, which is to ask a different set of questions entirely.

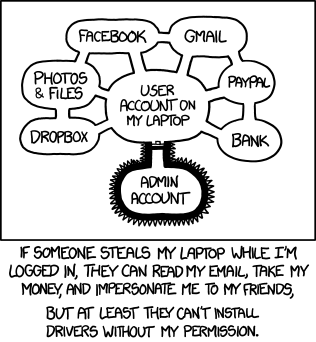

A web of third parties

I should start with a broad definition of what it is to be third party: If it’s a person and I don’t compensate them for the bulk of their workload, they’re third party. If it’s a company or service and I don’t control it, it’s third party. If it’s code and my team doesn’t grasp every line of it, it’s third party.

The third-party landscape is rapidly expanding. Github has grown to almost 7 million users and the WordPress plugin repo is approaching 1 billion downloads. Many of these solutions are easy for clients and competitors to implement; meanwhile, I’m still in the lab debugging my custom code. The idea of selling original work seems oddly…old-fashioned.

Yet with so many third-party options to choose from, there are more chances than ever to veer off-course.

What could go wrong?

At a meeting a couple of years ago, I argued against using an external service to power a search widget on a client project. “We should do things ourselves,” I said. Not long after this, on the very same project, I argued in favor of a using a third party to consolidate RSS feeds into a single document. “Why do all this work ourselves,” I said, “when this problem has already been solved?” My inconsistency was obvious to everyone. Being dogmatic about not using a third party is no better than flippantly jumping in with one, and I had managed to do both at once!

But in one case, I believed the third party was worth the risk. In the other, it wasn’t. I just didn’t know how to communicate those thoughts to my team.

I needed, in the parlance of our times, a decision-making framework. To that end, I’ve been maintaining a collection of points to think through at various stages of engagement with third parties. I’ll tour through these ideas using the search widget and the RSS digest as examples.

The difference between a request and a goal

This point often reveals false assumptions about what a client or stakeholder wants. In the case of the search widget, we began researching a service that our client specifically requested. Fitted with ajax navigation, full-text searching, and automated crawls to index content, it seemed like a lot to live up to. But when we asked our clients what exactly they were trying to do, we were surprised: they were entirely taken by the typeahead functionality; the other features were of very little perceived value.

In the case of the RSS “smusher,” we already had an in-house tool that took an array of feed URLs and looped through them in order, outputting x posts per feed in some bespoke format. They’re too good for our beloved multi-feed widget? But actually, the client had a distinctly different and worthwhile vision: they wanted x results from their array of sites in total, and they wanted them ordered by publication date, not grouped by site. I conceded.

It might seem like an obvious first step, but I have seen projects set off in the wrong direction because the end goal is unknown. In both our examples now, we’re clear about that and we’re ready to evaluate solutions.

To dev or to download

Before deciding to use a third party, I find that I first need to examine my own organization, often in four particular ways: strengths, weaknesses, betterment, and mission.

Strengths and weaknesses

The search task aligned well with our strengths because we had good front-end developers and were skilled at extending our CMS. So when asked to make a typeahead search, we felt comfortable betting on ourselves. Had we done it before? Not exactly, but we could think through it.

At that same time, backend infrastructure was a weakness for our team. We had happened to have a lot of turnover among our sysadmins, and at times it felt like we weren’t equipped to hire that sort of talent. As I was thinking through how we might build a feed-smusher of our own, I felt like I was tempting a weak underbelly. Maybe we’d have to set up a cron job to poll the desired URLs, grab feed content, and store that on our servers. Not rocket science, but cron tasks in particular were an albatross for us.

Betterment of the team

When we set out to achieve a goal for a client, it’s more than us doing work: it’s an opportunity for our team to better themselves by learning new skills. The best opportunities for this are the ones that present challenging but attainable tasks, which create incremental rewards. Some researchers cite this effect as a factor in gaming addiction. I’ve felt this myself when learning new things on a project, and those are some of my favorite work moments ever. Teams appreciate this and there is an organizational cost in missing a chance to pay them to learn. The typeahead search project looked like it could be a perfect opportunity to boost our skill level.

Organizational mission

If a new project aligns well with our mission, we’re going to resell it many times. It’s likely that we’ll want our in-house dev team to iterate on it, tailoring it to our needs. Indeed, we’ll have the budget to do so if we’re selling it a lot. No one had asked us for a feed-smusher before, so it didn’t seem reasonable to dedicate an R&D budget to it. In contrast, several other clients were interested in more powerful site search, so it looked like it would be time well spent.

We’ve now clarified our end goals and we’ve looked at how these projects align with our team. Based on that, we’re doing the search widget ourselves, and we’re outsourcing the feed-smusher. Now let’s look more closely at what happens next for both cases.

Evaluating the unknown

The frustrating thing about working with third parties is that the most important decisions take place when we have the least information. But there are some things we can determine before committing. Familiarity, vitality, extensibility, branding, and Service Level Agreements (SLAs) are all observable from afar.

Familiarity: is there a provider we already work with?

Although we’re going to increase the number of third-party dependencies, we’ll try to avoid increasing the number of third-party relationships.

Working with a known vendor has several potential benefits: they may give us volume pricing. Markup and style are likely to be consistent between solutions. And we just know them better than we’d know a new service.

Vitality: will this service stick around?

The worst thing we could do is get behind a service, only to have it shut down next month. A service with high vitality will likely (and rightfully) brag about enterprise clients by name. If it’s open source, it will have a passionate community of contributors. On the other hand, it could be advertising a shutdown. More often, it’s somewhere in the middle. Noting how often the service is updated is a good starting point in determining vitality.

Extensibility: can this service adapt as our needs change?

Not only do we have to evaluate the core service, we have to see how extensible it is by digging into its API. If a service is extensible, it’s more likely to fit for the long haul.

APIs can also present new opportunities. For example, imagine selecting an email-marketing provider with an API that exposes campaign data. This might allow us to build a dashboard for campaign performance in our CMS—a unique value-add for our clients, and a chance to keep our in-house developers invested and excited about the service.

Branding: is theirs strong, or can you use your own?

White-labeling is the practice of reselling a service with your branding instead of that of the original provider. For some companies, this might make good sense for marketing. I tend to dislike white-labeling. Our clients trust us to make choices, and we should be proud to display what those choices are. Either way, you want to ensure you’re comfortable with the brand you’ll be using.

SLAs: what are you getting, beyond uptime?

For client-side products, browser support is a factor: every external dependency represents another layer that could abandon older browsers before we’re ready. There’s also accessibility. Does this new third-party support users with accessibility needs to the degree that we require? Perhaps most important of all is support. Can we purchase a priority support plan that offers fast and in-depth help?

In the case of our feed-smusher service, there was no solution that ran the table. The most popular solution actually had a shutdown notice! There were a couple of smaller providers available, but we hadn’t worked with either before. Browser support and accessibility were moot since we’d be parsing the data and displaying it ourselves. The uptime concern was also diminished because we’d be sure to cache the results locally. Anyway, with viable candidates in hand, we can move on to more productive concerns than dithering between two similar solutions.

Relationship maintenance

If someone else is going to do the heavy lifting, I want to assume as much of the remaining burden as possible. Piloting, data collection, documentation, and in-house support are all valuable opportunities to buttress this new relationship.

As exciting as this new relationship is, we don’t want to go dashing out of the gates just yet. Instead, we’ll target clients for piloting and quarantine them before unleashing it any further. Cull suggestions from team members to determine good candidates for piloting, garnering a mix of edge-cases and the norm.

If the third party happens to collect data of any kind, we should also have an automated way to import a copy of it—not just as a backup, but also as a cached version we can serve to minimize latency. If we are serving a popular dependency from a CDN, we want to send a local version if that call should fail.

If our team doesn’t have a well-traveled directory of provider relationships, the backstory can get lost. Let a few months pass, throw in some personnel turnover, and we might forget why we even use a service, or why we opted for a particular package. Everyone on our team should know where and how to learn about our third-party relationships.

We don’t need every team member to be an expert on the service, yet we don’t want to wait for a third-party support staff to respond to simple questions. Therefore, we should elect an in-house subject-matter expert. It doesn’t have to be a developer. We just need somebody tasked with monitoring the service at regular intervals for API changes, shutdown notices, or new features. They should be able to train new employees and route more complex support requests to the third party.

In our RSS feed example, we knew we’d read their output into our database. We documented this relationship in our team’s most active bulletin, our CRM software. And we made managing external dependencies a primary part of one team member’s job.

DIY: a third party waiting to happen?

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: a prideful developer assures the team that they can do something themselves. It’s a complex project. They make something and the company comes to rely on it. Time goes by and the in-house product is doing fine, though there is a maintenance burden. Eventually, the developer leaves the company. Their old product needs maintenance, no one knows what to do, and since it’s totally custom, there is no such thing as a community for it.

Once you decide to build something in-house, how can you prevent that work from devolving into a resented, alien dependency?

- Consider pair-programming. What better way to ensure that multiple people understand a product, than to have multiple people build it?

- “Job-switch Tuesdays.” When feasible, we have developers switch roles for an entire day. Literally, in our ticketing system, it’s as though one person is another. It’s a way to force cross-training without doubling the hours needed for a task.

- Hold code reviews before new code is pushed. This might feel slightly intrusive at first, but that passes. If it’s not readable, it’s not deployable. If you have project managers with a technical bent, empower them to ask questions about the code, too.

- Bring moldy code into light by displaying it as phpDoc, JSDoc, or similar.

- Beware the big. Create hourly estimates in Fibonacci increments. As a project gets bigger, so does its level of uncertainty. The Fibonacci steps are biased against under-budgeting, and also provide a cue to opt out of projects that are too difficult to estimate. In that case, it’s likely better to toe-in with a third party instead of blazing into the unknown by yourself.

All of these considerations apply to our earlier example, the typeahead search widget. Most germane is the provision to “beware the big.” When I say “big,” I mean that relative to what usually works for a given team. In this case, it was a deliverable that felt very familiar in size and scope: we were being asked to extend an open-source CMS. If instead we had been asked to make a CMS, alarms would have gone off.

Look before you leap, and after you land

It’s not that third parties are bad per se. It’s just that the modern web team strikes me as a strange place: not only do we stand on the shoulders of giants, we do so without getting to know them first—and we hoist our organizations and clients up there, too.

Granted, there are many things you shouldn’t do yourself, and it’s possible to hurt your company by trying to do them—NIH is a problem, not a goal. But when teams err too far in the other direction, developers become disenfranchised, components start to look like spare parts, and clients pay for solutions that aren’t quite right. Using a third party versus staying in-house is a big decision, and we need to think hard before we make it. Use my line of questions, or come up with one that fits your team better. After all, you’re your own best dependency.

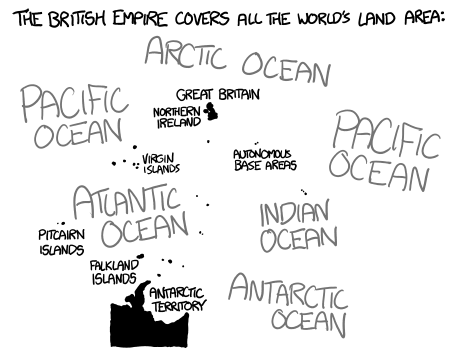

Sunset on the British Empire

Sunset on the British Empire

When (if ever) did the Sun finally set on the British Empire?

—Kurt Amundson

It hasn't. Yet. But only because of a few dozen people living in an area smaller than Disney World.

The world's largest empire

The British Empire spanned the globe. This led to the saying that the Sun never set on it, since it was always daytime somewhere in the Empire.

It's hard to figure out exactly when this long daylight began. The whole process of claiming a colony (on land already occupied by other people) is awfully arbitrary in the first place. Essentially, the British built their empire by sailing around and sticking flags on random beaches.[1] This makes it hard to decide when a particular spot in a country was "officially" added to the Empire.

The exact day when the Sun stopped setting on the Empire was probably sometime in the late 1700s or early 1800s, when the first Australian territories were added.[2]

The Empire largely disintegrated in the early 20th century, but—surprisingly—the Sun hasn't technically started setting on it again.

Fourteen territories

Britain has fourteen overseas territories, the direct remnants of the British Empire.[3]

(Many newly-independent British colonies joined the Commonwealth of Nations. Some of them, like Canada and Australia, have Queen Elizabeth as their official monarch. But they are independent states which happen to have the same queen; they are not part of any empire that they know of.)

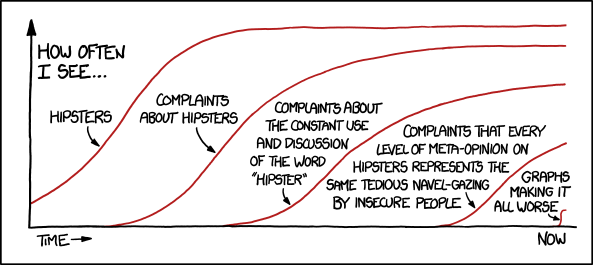

The Sun never sets on all fourteen British territories at once (or even thirteen, if you don’t count the British Antarctic Territory). However, if the UK loses one tiny territory, it will experience its first Empire-wide sunset in over two centuries.

Every night, around midnight GMT, the Sun sets on the Cayman Islands, and doesn't rise over the British Indian Ocean Territory until after 1:00 AM. For that hour, the little Pitcairn Islands in the South Pacific are the only British territory in the Sun.

The Pitcairn Islands have a population of a few dozen people, the descendants of the mutineers from the HMS Bounty. The islands became notorious in 2004 when a third of the adult male population, including the mayor, were convicted of child sexual abuse.[4][5]

As awful as the islands may be, they remain part of the British Empire, and unless they're kicked out, the two-century-long British daylight will continue.

Will it last forever?

Well, maybe.

Four hundred years from now, in April of 2432, the island will experience its first total solar eclipse since the mutineers arrived.[6]

Luckily for the Empire, the eclipse happens at a time when the Sun is over the Cayman Islands in the Caribbean. Those areas won't see a total eclipse; the Sun will even still be shining in London.

In fact, no total eclipse for the next thousand years will pass over the Pitcairn Islands at the right time of day to end the streak. If the UK keeps its current territories and borders, it can stretch out the daylight for a long, long time.

But not forever. Eventually—many millennia in the future—an eclipse will come for the island, and the Sun will finally set on the British Empire.

![The walls of Buckingham Palace are lined with [in case of emergency, break glass] boxes. Inside each one is a cup of tea.](http://what-if.xkcd.com/imgs/a/48/empire_eclipse.png)