Shared posts

Saturday assorted links

2. “The 1970 census found 42% of black households owned their own homes. Today, the number is also 42%.” Link here.

3. Puffin beaks are fluorescent and we had no idea discovery by accident. By the way “”They can see colours that we can’t comprehend,” Dunning said.”

The post Saturday assorted links appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

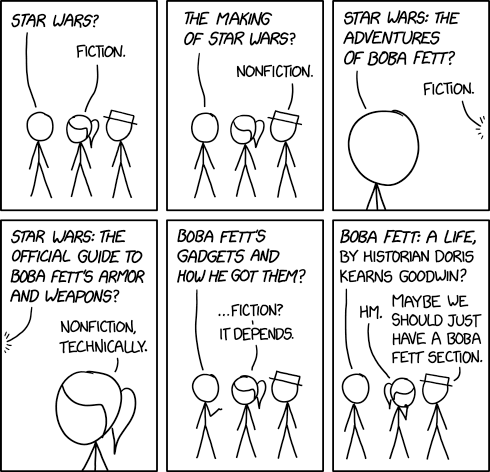

Why I'm Not a Beer Geek

Yesterday, on the discussion-resistant platform of Twitter, I had a choppy exchange about the nature of the beer geek. I argued that I wasn't one, and Nick concluded, "Hilarious to think that a guy who writes books about beer and travels the world to explore rare styles denies being [a beer geek]." (New motto!: "Providing inadvertent hilarity since 2006 ™.") Let's take it off the Twitter and break this whole thing down. I have lately noticed quite a deviation in my own behavior and that of many other beer fans, and it seems worth a paragraph or seven of exploration.

If "beer geek" is a general category identifying anyone who knows what a session IPA is, then I and anyone reading this fit the bill. I think that's Nick's point. Until ten years ago, that was a useful category because the number of people drinking good beer was relatively small. We were already a subculture. But now a majority of beer drinkers are at least sometime "craft" (read: anything but mass market lager) drinkers. Which means this use of beer geek would mean most people who drink beer, and would therefore be drained of any real meaning.

Even more to the point, there's a big difference behaviorally, and this is where I've noticed it. A subculture of super-fans has developed, and they behave in distinctive ways. They spend a lot of time pursuing new beers and are very trend-sensitive. They are the first adopters, lavishing love on beers like "New England IPAs" (right now), kettle-soured beers (last year), or fruit IPAs (2014). They are hugely promiscuous in their fandom, trying to taste as much beer from as many breweries as possible. They have strong opinions about the best breweries and beers and organize them into tiers of coolness, much like music fans. They dream about landing ultra-rare, usually vintage beers ("whales"). They'll stand in line for hours to get a bottle of the latest, coolest beer--or even drive to Vermont so they can stand in line for hours to get one. They avidly record their activities on various social media apps and ratings sites. When they travel abroad, they want to drink as many different beers as possible, and may go to six pubs in an evening. This is the person I think of as a beer geek.

It lines up pretty closely with the way people describe geeks in other subcultures, too. In fact, people have drawn a distinction between nerds and geeks to give the term extra valence:

Geeks are “collection” oriented, gathering facts and mementos related to their subject of interest. They are obsessed with the newest, coolest, trendiest things that their subject has to offer.... Nerds are “achievement” oriented, and focus their efforts on acquiring knowledge and skill over trivia and memorabilia.We don't regularly use the phrase "beer nerd," but I guess it would, in Nick's words, describe a guy who "writes books about beer and travels the world to explore rare styles." I'm definitely far more nerdy than geeky. But there's another dimension here that goes back to the behavior bit, and it's the one that makes me think I'm not a beer geek--and maybe only nerd-adjacent. Beer is unlike sci-fi or just plain sci in that it has an attendant culture and context of use. And this gets to where my interests lie.

|

| Source |

There are other subgroups within beer fandom (the historians/scholars, the homebrewers, the style nazis, the low-information drinkers), but if I had to identify my tribe, it would be the pub-goers. This has given rise in the past five years to conversations that peter out after I confess I haven't tried some new beer or been to a newly-opened brewery. (And by newly-opened I mean since 2010.) It means I end up defending low-status beers in conversations with mystified geeks. Weirdly, it also means that some of my beery interests--an old European brewery I've visited, some weird technique a brewer told me about--are met with glazed eyes by bored geeks. The rise of this kind of beer geek is fairly recent--super-fans didn't exist in enough density to coagulate into a subculture until maybe ten years ago. But now beer geekery is a full-fledged subculture, and its rules, values, and membership mystify me. I am not a beer geek.

Update

This post has spent 24 hours percolating through social media, and there's a vein within the chatter I'd like to respond to. The idea with the post was to point out that a new subculture within beer has developed. I don't think semantics matter here--whether that or another subculture, or even the whole of beer fandom, gets called "beer geek" isn't really the point. The point is more that there now are many different currents within the beer-enjoying community and I feel somewhat out of step with some of them.

I'd like to add that, although I don't see myself as a beer geek in the way paragraph three describes them, I have nothing against those who are. Fandom is like anything--your preferences may vary. I have much more in common with whale-hunters than I do with Bud Light drinkers. We don't need to play our expressions of fandom against one another.

The world’s flags, in 7 charts

The graphics below categorize the flags of the world in fascinating ways — by color, age and design. Created by Ferdio, a design agency that makes infographics, they will show you everything you wanted to know about flags, and maybe more. You can click on the graphics to enlarge them.

1. Most of the world's flags aren't that old. The timeline below shows the date each nation adopted its current national flag. The vast majority were adopted in the past 200 years.

Ferdio

2. No country has a purple flag. Some countries have flags that are bluish-purplish, but none are purple outright, Ferdio said. As the graphic below shows, primary colors predominate.

Ferdio

3. Red, white and blue is the most popular color combo. The U.S. colors aren't that unique — a plurality of the world's flags are red, white and blue. Pan-African and Pan-Arabic color combinations are in fourth and fifth place.

Ferdio

4. Most countries go for three or four colors. Some flags have two colors, but far fewer have five or six.

Ferdio

5. Flags have families, too. As you might have noticed from the graphics before, there are specific families that some flags fall into, by culture or region. The flags of Nordic countries all boast a Scandinavian cross, while Pan-Arab and Pan-African flags sport similar colors.

Ferdio

6. A star is the most commonly used symbol. More than two-thirds of flags have symbols, mostly stars, shields, crosses, suns and moons.

Ferdio

7. Most flag designs stick to the simple. Ferdio used Adobe Illustrator to analyze the number of vector points in each flag — basically, where a line changes direction. They found that many flags are relatively simple, but some have thousands of vector points.

Ferdio

You might also like:

What’s straight across the ocean when you’re at the beach

The history of the world, as you’ve never seen it before

Fascinating maps show the different places locals and tourists go in 19 major cities

Olympic-Level Troll Hijacks HLN Segment on Edward Snowden to Defend Edward Scissorhands

The Founding Myth of the United States of America

Guest post by Benjamin Naimark-Rowse

A teapot from shortly before the American Revolution. By the National Museum of American History.

This past weekend, cities and towns from coast-to-coast hosted fireworks, concerts, and parades to celebrate our independence from Britain. Those celebrations invariably highlight the soldiers who pushed the British from our shores. But the lesson we learn of a democracy forged in the crucible of revolutionary war tends to ignore how a decade of nonviolent resistance before the shot-heard-round-the-world shaped the founding of the United States, strengthened our sense of political identity, and laid the foundation of our democracy.

We’re taught that we won our independence from Britain through bloody battles. We recite poetry about the midnight ride of Paul Revere that warned of a British attack. And we’re shown depictions of Minutemen in battle with Redcoats in Lexington and Concord.

I grew up in Boston where our veneration for revolutionary battles against the British extends far beyond the Fourth of July. We celebrate Patriots’ Day to commemorate the anniversary of the first battles of the Revolution and Evacuation Day to commemorate the day British troops finally fled Boston. And at the start of every Red Sox game we stand, take off our hats, and sing – thirty-three thousand strong – about the perilous fight, the rockets’ red glare, and the bombs bursting in air that gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.

Yet, Founding Father, John Adams wrote that, “A history of military operations…is not a history of the American Revolution.”

American Revolutionaries led not one, but three nonviolent resistance campaigns in the decade before the Revolutionary War. These campaigns were coordinated. They were primarily nonviolent. They helped politicize American society. And they allowed colonists to replace colonial political institutions with parallel institutions of self-government that help form the foundation of the democracy that we rely on today.

The first nonviolent resistance campaign was in 1765 against the Stamp Act. Tens of thousands of our forbearers refused to pay the British king a tax simply to print legal documents and newspapers, by collectively deciding to halt consumption of British goods. The ports of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia signed pacts against importing British products; women made homespun yarn to replace British cloth; and eligible bachelorettes in Rhode Island even refused to accept the addresses of any man who supported the Stamp Act.

Colonists organized the Stamp Act Congress. It passed statements of colonial rights and limits on British authority, and sent copies to every colony as well as one copy to Britain thereby demonstrating a united front. This mass political mobilization and economic boycott meant the Stamp Act would cost the British more money than it was worth to enforce leaving it dead on arrival. This victory also demonstrated the power of nonviolent non-cooperation: people-powered defiance of unjust social, political, or economic authority.

The second nonviolent resistance campaign started in 1767 against the Townshend Acts. These acts taxed paper, glass, tea, and other commodities imported from Britain. When the Townsend Acts went into effect, merchants in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia again stopped importing British goods. They declared that anyone continuing to trade with the British should be labeled “enemies of their country.” A sense of a new political identity detached from Britain grew across the colonies.

By 1770, colonists developed the Committees of Correspondence, a new political institution detached from British authority. The committees allowed colonists to share information and coordinate their opposition. The British Parliament reacted by doubling down and taxing tea, which led enraged members of the Sons of Liberty to carry out the infamous Boston Tea Party.

The British Parliament countered with the Coercive Acts, which effectively cloistered Massachusetts. The port of Boston was closed until the British East India Company was repaid for their Tea Party loses. Freedom of assembly was officially limited. And court trials were moved from Massachusetts.

In defiance of the British, colonists organized the First Continental Congress. Not only did they articulate their grievances against the British, colonists also created provincial congresses to enforce the rights they declared unto themselves. A newspaper at the time reported that these parallel legal institutions effectively took government out of the hands of British appointed authorities and placed it in the hands of the colonists so much so that some scholars assert that, “independence in many of the colonies had essentially been achieved prior to the commencement of military hostilities in Lexington and Concord.”

King George III felt that this level of political organization had gone too far, noting that; “…The New England Governments are in a State of Rebellion; blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this Country or independent.” In response, colonists organized the Second Continental Congress, appointed George Washington Commander in Chief and so began eight years of violent conflict.

The Revolutionary War may have physically kicked the British off our shores, but this past weekend’s focus on war obscures the contributions that nonviolent resistance made to the founding of our country.

During the decade leading up to the war, colonists articulated and debated political decisions in public assemblies. In so doing, they politicized society and strengthened their sense of a new political identity free from the British. They legislated policy, enforced rights, and even collected taxes. In so doing, they practiced self-governance outside of wartime. And they experienced the power of nonviolent political action across the broad stretches of land that were to become the United States of America.

So on future Independence Days, let us celebrate our forefathers’ and mothers’ nonviolent resistance to British colonial rule. And every day as we deliberate the myriad challenges facing our democracy, let us draw on our nonviolent history just as John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington did over two centuries ago.

Benjamin Naimark-Rowse is a Truman National Security Fellow. He teaches and studies nonviolent resistance at The Fletcher School at Tufts University.

Filed under: Governance, Protest, Repression, War Tagged: American Revolution, Nonviolence, United Kingdom, United States

The data must be free!

Ben Goldacre has once again produced some excellent writing on scientific data — he has written an article on data analysis and deworming trials, and it’s both interesting and important. I’ll be using it in my classes, because I do try to hammer home to my students the importance of an appropriate understanding of statistics.

The main point, though, is that science has a problem. In a discipline dependent on the free exchange of information, huge amounts of data are hidden away and locked up as ‘proprietary information’, and all that gets published are basically synopses and interpretations.

Two years ago I published a book on problems in medicine. Front and center in this howl was “publication bias,” the problem of clinical trial results being routinely and legally withheld from doctors, researchers, and patients. The best available evidence — from dozens of studies chasing results for completed trials — shows that around half of all clinical trials fail to report their results. The same is true of industry trials, and academic trials. What’s more, trials with positive results are about twice as likely to post results, so we see a biased half of the literature.

This is a cancer at the core of evidence-based medicine. When half the evidence is withheld, doctors and patients cannot make informed decisions about which treatment is best. When I wrote about this, various people from the pharmaceutical industry cropped up to claim that the problem was all in the past. So I befriended some campaigners, we assembled a group of senior academics, and started the AllTrials.net campaign with one clear message: “All trials must be registered, with their full methods and results reported.”

How else can results be confirmed and replicated?

If you watch one thing on Ebola, make it this

Jim.PavlikI know this is about a week old or so, but man, it's good. Sam Shephard is sounding pretty Cronkite-y here. Impressive.

I’ve been travelling, so I didn’t get to post this until now. If you watch one thing on Ebola, make it this:

Last year, I wished TIE had a media award, so I could give it to Peggy Orenstein. I think Shep Smith has locked up the 2014 award with the above.

“How do you do it all?”

People often ask me how I “do it all.” I think they mean all the blogging, on top of my regular job as a researcher. The simple answer is, I work a lot, much of it in short intervals of time away from my office.

But I very much doubt I work more than the average person who asks, “How do you do it all?” It’s just that a substantial amount of my work product is highly visible: the blogging. I think that gives the impression that I’m doing more in less time.

For all that, I may, in fact, manage time well, as I’ve been told by others for years. People have asked me for time management tips since I was in high school. As has Tyler Cowen and some of the “most productive people on the planet”, I’ve written some down for you below and in no particular order. These are just some aspects of how I generally work and live, only some of which may enhance my productivity.

- I do not work to deadlines. I start early and revise often. I first drafted this post five days ago.

- I keep my pipeline full. I always have stuff to do, to write about, to read. I don’t wonder, “What should I write? What should I read?” I have lists.

- I have many things in process at once. For example, at the moment I have over a dozen posts for various outlets in different states of completion. Some are done. Others are lists of links or notes.

- I protect the morning for the hardest work of the day, requiring the greatest concentration. I try to schedule meetings and calls for the afternoon. I read papers in the afternoons or evenings, with one major exception (see next item).

- I don’t drive on my commute. I walk and take the train. Walking (up to 6 miles per day) replaces what would otherwise be time spent at a gym or similar. During my commute, I catch up on news and, yes, some entertainment by podcast (at 2x speed—people speak too slowly). I read and take care of email on the train.

- I use Twitter, but mindfully. When I don’t have time for it, I ignore it. When I need a short break, I look at it. This has the advantage of combining some entertainment (which is what I seek during a break) with a lot of valuable information (given whom I follow). What feels like a break ends up being more useful, without my even noticing.

- Otherwise, I don’t read a lot of “news.” I read nothing out of a sense of obligation. I skim things in my RSS reader, sometimes flip through The New York Times online or in an app.

- I stop reading or just skim ahead things that are not well written, don’t speak to me, or don’t teach me anything. Sometimes I read posts and articles backwards (last paragraph, next to last, and so forth). I’m hunting for the incremental update.

- I watch little TV. I miss most movies.

- I reply to email that I intend to respond to at all within minutes, typically (except when circumstances do not allow). This probably isn’t productivity enhancing. I just think my colleagues and friends appreciate the responsiveness. Providing it makes me feel nice and useful.

- Unless I have a unique take, I don’t write about things that many others are.

- I seek feedback on my products, listen to it, and make changes as warranted.

- I’m nearly completely paper free. All my work products’ inputs and outputs are electronic and in the cloud. Same goes for life management tools like my calendar.

- I rarely take notes. When I do, they’re either electronic to begin with or transferred to electronic rapidly and where they need to be for future use.

- I try to remember where to find useful information, rather than trying to remember all the useful information. This is why I blog and tweet. They’re searchable memory aids. Also, I am fortunate to have access to highly reliable, external (human) memory.

- I ignore most office and institutional politics, skip every possible meeting, and don’t pay close attention at all times in most of those I attend. (These habits can be potentially dangerous. I have some protective workarounds, which rely on the skills, interests, and good will of others. Gains from trade.)

- I don’t take calls that are not pre-arranged and with people I want to talk to. I don’t listen to voicemail promptly, if at all.

- I say “yes” only to things I feel I can do well given the amount of time I think is asked of me. (Doing something well implies I want to do it.)

- When I take breaks, they are real breaks, without guilt. When needed, I have blown off weeks of evenings playing video games or reading novels. I take internet-free vacations. I trust myself that my motivation to work hard will return, but don’t force it. It always works out. (This takes practice.)

- I love to learn and write. I don’t try to do it. I feel a need for it. Then I just do it.

Two final points: Information in any form (reading, TV, podcasts/radio, the content of meetings, emails, and so forth) is almost entirely entertainment, with little lasting informational value. How much do you recall from a book you read three years ago, a movie you saw one year ago, an hour-long conference call you were on last month, an article you read last week, or a radio program you listened to three days ago? How much can you write down about it? What was the key point or message? With few exceptions, what took many minutes or hours to consume has been converted to, at most, a few sentences of information in your long-term memory. The rest of the information is not retained. From a long-term perspective, most of what you consumed was filler, momentary entertainment (if that), packaging, art, which is all fine and good, but not necessarily memorable information. For gathering information of long-term value, skipping or skimming the likely non-memorable parts and finding ways to codify in a searchable form the important, new information is more efficient, though not necessarily easy. (If one is seeking entertainment, inspiration, and the like, this is not applicable. I like art too!)

Finally, there are many other ways to be productive and types of productive people. Some of my very productive cobloggers work in very different styles, for instance. It leads me to suspect that one is not productive because of one’s methods, but one is simply productivity-oriented first and then develops personalized methods to suit.

Notes From a First Foray into Text Mining

Guess what? Text mining isn’t push-button, data-making magic, either. As Phil Schrodt likes to say, there is no Data Fairy.

I’m quickly learning this point from my first real foray into text mining. Under a grant from the National Science Foundation, I’m working with Phil Schrodt and Mike Ward to use these techniques to develop new measures of several things, including national political regime type.

I wish I could say that I’m doing the programming for this task, but I’m not there yet. For the regime-data project, the heavy lifting is being done by Shahryar Minhas, a sharp and able Ph.D. student in political science at Duke University, where Mike leads the WardLab. Shahryar and I are scheduled to present preliminary results from this project at the upcoming Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association in Washington, DC (see here for details).

When we started work on the project, I imagined a relatively simple and mostly automatic process running from location and ingestion of the relevant texts to data extraction, model training, and, finally, data production. Now that we’re actually doing it, though, I’m finding that, as always, the devil is in the details. Here are just a few of the difficulties and decision points we’ve had to confront so far.

First, the structure of the documents available online often makes it difficult to scrape and organize them. We initially hoped to include annual reports on politics and human-rights practices from four or five different organizations, but some of the ones we wanted weren’t posted online in a format we could readily scrape. At least one was scrapable but not organized by country, so we couldn’t properly group the text for analysis. In the end, we wound up with just two sets of documents in our initial corpus: the U.S. State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, and Freedom House’s annual Freedom in the World documents.

Differences in naming conventions almost tripped us up, too. For our first pass at the problem, we are trying to create country-year data, so we want to treat all of the documents describing a particular country in a particular year as a single bag of words. As it happens, the State Department labels its human rights reports for the year on which they report, whereas Freedom House labels its Freedom in the World report for the year in which it’s released. So, for example, both organizations have already issued their reports on conditions in 2013, but Freedom House dates that report to 2014 while State dates its version to 2013. Fortunately, we knew this and made a simple adjustment before blending the texts. If we hadn’t known about this difference in naming conventions, however, we would have ended up combining reports for different years from the two sources and made a mess of the analysis.

Once ingested, those documents include some text that isn’t relevant to our task, or that is relevant but the meaning of which is tacit. Common stop words like “the”, “a”, and “an” are obvious and easy to remove. More challenging are the names of people, places, and organizations. For our regime-data task, we’re interested in the abstract roles behind some of those proper names—president, prime minister, ruling party, opposition party, and so on—rather than the names themselves, but text mining can’t automatically derive the one for the other.

For our initial analysis, we decided to omit all proper names and acronyms to focus the classification models on the most general language. In future iterations, though, it would be neat if we could borrow dictionaries developed for related tasks and use them to replace those proper names with more general markers. For example, in a report or story on Russia, Vladimir Putin might get translated into <head of government>, the FSB into <police>, and Chechen Republic of Ichkeria into <rebel group>. This approach would preserve the valuable tacit information in those names while making it explicit and uniform for the pattern-recognition stage.

That’s not all, but it’s enough to make the point. These things are always harder than they look, and text mining is no exception. In any case, we’ve now run this gantlet once and made our way to an encouraging set of initial results. I’ll post something about those results closer to the conference when the paper describing them is ready for public consumption. In the meantime, though, I wanted to share a few of the things I’ve already learned about these techniques with others who might be thinking about applying them, or who already do and can commiserate.

This may be the greatest conversation I’ve ever had

Jim.PavlikHow could I possibly add anything to this?

SEK went to the supermarket to pick up tuna fish for his elderly cat who now only eats food that also contains tuna. As tuna is on sale, he purchases twenty cans of it and is on the checkout line in front of POLITE DRUNK MAN.

POLITE DRUNK MAN: You don’t eat all them cans, now?

SEK: Wasn’t planning on it.

POLITE DRUNK MAN: TV say they full of Menicillin.

SEK: Mercury?

POLITE DRUNK MAN: Menicillin, bad for the children, real bad.

SEK: I promise not to share it with any kids.

POLITE DRUNK MAN: Menicillin’s terrible, make ‘em have miscarriages.

SEK: The kids?

POLITE DRUNK MAN: Ain’t even get a chance to be kids, they born miscarried, or with arms.

SEK: I’ll keep that in mind.

POLITE DRUNK MAN: Dead babies with arms, that’s what Menicillin do. Best watch out.

SEK: I will, promise.

Beer vs Wine, Again, for Some Reason

So I’ve been loving Vox.com lately. If I had a few hundred hours a week to waste, I would probably waste them reading the stories and associated “cards” on Vox. At least until I got caught up. Most of what I read there is either personally interesting (politics and political science!), some of it is professionally useful (marijuana) and some of it, sometimes, fits here. So I encourage to you to go over to Vox and read the story that originally accompanied these maps I yoinked. I will not recapitulate their points here. Instead, I will point out some things about the first map they didn’t, either because they did not know, did not care, or did not think were more generally interesting for their audience.

So, of this map, Vox says “the coasts like wine, beer is popular inland.” Yeah, generally, I guess. Except wine is actually the dominant drink in New England, Florida, northern California, a strange pocket in northwest Arkansas, and on the fringes of the Pacific northwest. Beer shares dominance in over 50% of the coastal regions which Vox implies are wine-dominant areas. I only see on surprising thing here, which I’ll get to in a moment. For two reasons (not necessarily unrelated) wine should be popular precisely where it is popular.

Wine is expensive. For most of its life, beer was canned primarily with some bottles. Then craft came along and bottles dominated that sector and now craft brewers are canning again. But wine is bottled (except in some cases when it is bagged and boxed). Also, grapes are harder to ship than any of the ingredients in beer. These two factors (big heavy glass bottles and expensive-to-ship raw ingredients) have always meant that wine has tended to stay close to home. That is not to say that wine has not enjoyed international markets. We know that the ancient Greeks were trading deep into Europe and wine went with them, the Romans too. But the vast majority of wine is drunk locally, primarily because of logistics, which combine to make an expensive product even more so. Those ancient Greek and Roman wine traders were dealing in true luxury items. So it isn’t at all weird that wine would be most popular in those areas where grapes are grown and then secondarily where people can afford to buy it.

As we know from several repetitions on this site, as people get richer, they move their drinking toward wine. And, as Vox notes, wine seems to be an urban phenomena (where, on average, people have more money). Note that wine outpaces beer in northern Virginia (some of the most expensive counties in the country) and continues north through eastern Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and the southern parts of Connecticut and Vermont. On the west coast wine begins dominance in (roughly) Orange County (the “OC”) and continues north through the wine growing region. Also in Colorado Springs (deep inland, but also very rich). As a matter of fact, check out this map of the most expensive counties. It isn’t very finely detailed but you can see that the red areas more or less correspond to the dark areas on the wine map. The blue dots travel the western edge of that shared wine/beer area along the Mississippi River.

Speaking of that one weird thing, that area along the Mississippi River, what is going on there? From Vox’s headline implication, it could just be that we should treat the Mississippi River area as a “coast,” but it is unclear what that would mean. Sure it has shipping, like the coasts, but analyzing the Mississippi as coastal because of shipping should indicate that the Great Lakes region should have some wine popularity too. It’s one of the poorer regions of the country. Obviously this isn’t a “coastal elite” thing. I credit two things. Shipping helps. Shipping over water is more efficient (read: cheap) than shipping overland, so getting wine to the region isn’t as expensive as say, getting it to Denver and down into “The Springs.” But shipping from where? One would suppose that wine dominance would leave a trail along its logistical path if the mere presence of wine could inspire a change in palates. So where’s the trail leading from Sonoma to the Mississippi or from Albany to New Orleans? It doesn’t exist. I think it has more to do with this.

Specifically I think we’re seeing an artifact of that region’s early French influence. It’s not just architecture folks. Those things, like a preference for wine, linger. Notice the dark region on the wine map and compare it to the area on the map above called New France (not the one in Canada, the one where New Orleans is). From there straight north to St. Louis, which, if you’ve ever been to it, you know has a French influence (not just in its name, but that’s a pretty good hint). North of that it was all Bohemian, Scotch, and German farmers. Here’s the description of New France from the article linked above:

NEW FRANCE. Occupying the New Orleans area and southeastern Canada, New France blends the folkways of ancien régime northern French peasantry with the traditions and values of the aboriginal people they encountered in northeastern North America. After a long history of imperial oppression, its people have emerged as down-to-earth, egalitarian, and consensus driven, among the most liberal on the continent, with unusually tolerant attitudes toward gays and people of all races and a ready acceptance of government involvement in the economy. The New French influence is manifest in Canada, where multiculturalism and negotiated consensus are treasured.

I had initially planned to discuss all five maps, but I also didn’t expect to spend so much time on this one. Another time, perhaps.

Share and Enjoy:

Zombie Medicaid arguments

The following is co-authored by Aaron and Austin.

They just won’t die. Evidently, the House Republican budget is going to take another whack at Medicaid reform. Today, from the WaPo:

Medicaid, which provides health coverage to low-income families, is the object of a sharply worded review. “Medicaid coverage has little effect on patients’ health,” the report says, adding that it imposes an “implicit tax on beneficiaries,” “crowds out private insurance” and “increases the likelihood of receiving welfare benefits.”

There are studies documenting circumstances under which Medicaid can substantially “crowd out” private insurance. But, as has been explained on TIE, those circumstances don’t necessarily apply to the ACA. Moreover, many people at the low end of the socio-economic spectrum have the option of Medicaid or nothing. They make less than 138% of the poverty line. They aren’t able to afford insurance without massive subsidies.

But, as always, we want to focus on the first statement, the one that declares that Medicaid doesn’t improve patients’ health. That’s not true.

Does anyone really dispute that having health insurance is better than not having health insurance? Anyone who does should put their money where their mouth is. Mediaid isn’t welfare. You don’t get cash. It pays for health care if you need it. And, like all health insurance, it makes people healthier and saves lives. Lots of people say so. Studies confirm this.

A lot of the research that “shows Medicaid is bad” is flawed or misunderstood.

That research could be improved with the use of better research design, and methodologically stronger studies have shown that Medicaid is good for HIV mortality, child health, infant mortality, and more.

Which brings us to the Oregon Health Study, an actual randomized controlled trial of Medicaid. We have both written on early results. We’ve also commented on the later results, which are the ones people often seize upon to discredit Medicaid. Again.

People say that it does little to improve the health of people who have diabetes, who are at risk for heart disease, who have high cholesterol, or who have high blood pressure. There are real problems with those assertions. The Oregon study was not powered to detect improvements in those domains. We’re sorry, but it wasn’t. Here’s Austin explaining how it wasn’t set up to detect major changes in cholesterol or the Framingham Risk Score. Here’s Aaron talking about how it couldn’t detect changes in hypertension because the vast majority of people didn’t have it, and the assumptions that underlie arguments for being able to see a change aren’t on point. Same goes for diabetes.

Here’s a summary of those issues.

Why do people have insurance? Most people have it to protect themselves from financial ruin should they get really ill. But they also get it because it provides them the ability and incentive to get health care if they need it. Medicaid is about access. It’s just the first step in the chain of events that leads to better health and wellbeing. It’s not sufficient, but it is often necessary.

Many who argue that insurance should immediately and significantly make a population healthier are glossing over these other issues. They also seem not to care that there are no good RCTs proving that private insurance (or Medicare) do this.

There are lots of legitimate claims to make against Medicaid. It under-reimburses physicians, for instance, causing access problems in some areas and for some beneficiaries. (Guess what. Those problems are even worse for the uninsured, though.) But the natural response to saying docs don’t get paid enough would be to increase Medicaid funding to improve that. Gutting the program will do the opposite.

And let’s live in the real world here. Cutting Medicaid will be hard and painful. It will have serious consequences.

We look forward to a continuing and lively debate on how to reform the health care system. But declaring that health insurance in the form of Medicaid hurts people or “doesn’t work” ignores the real good that it does for so many people. (And, come on, health insurance is just pushing money around—it isn’t medicine or procedures.) Let’s listen to each other’s arguments and respond to them, instead of repeating talking points past each other.

Why Shakespeare liked ale but didn’t like beer

Jim.PavlikIt's long but if you want a glance into the life and times of Shakespeare from a brewers/beer drinkers perspective, well...here it is.

An old friend of mine gained a PhD in the relative clauses of William Shakespeare, with particular emphasis on the later plays. Ground-breaking stuff, she told me, and I’m sure that’s true. My own contribution to Shakespearian studies is rather less linguistic and more alcoholic: I seem to be the first person in centuries of scholarly study of the works of the Bard of Avon to point out that his plays clearly show Shakespeare was a fan of ale, but didn’t much like beer.

To appreciate this you have to know that, even in the Jacobean era, ale, the original English unhopped fermented malt drink, was still regarded as different, and separate, from, beer, the hopped malt drink brought over from continental Europe at the beginning of the 15th century, 200 years earlier. It was made by different people: Norwich had five “comon alebrewers” and nine “comon berebrewars” in 1564. In 1606 (the year Macbeth was performed at the Globe theatre) the town council of St Albans, 25 or so miles north of London, agreed to restrict the number of brewers in the town to four for beer and two for ale, to try to halt a continuing rise in the price of fuelwood.

This separation of fermented malt drinks in England into ale and beer continued right through to the 18th century, and can still be found in the 19th century, though the only difference by then was that ale was regarded as less hopped than beer. Even in Shakespeare’s time, brewers were starting to put hops into ale, though this was uncommon. In 1615, the year before Shakespeare died, Gervase Markham published The English Huswife, a handbook that contains “all the virtuous knowledges and actions both of the mind and body, which ought to be in any complete woman”. In it, Markham wrote that

“the general use is by no means to put any hops into ale, making that the difference between it and beere … but the wiser huswives do find an error in that opinion, and say the utter want of hops is the reason why ale lasteth so little a time, but either dyeth or soureth, and therefore they will to every barrel of the best ale allow halfe a pound of good hops

.

The book’s recipe for strong March beer included a quarter of malt and “a pound and a half of hops to one hogshead,” which may be three times more hops than Markham was recommending for ale, but is still not much hops by later standards, though Markham said that “This March beer … should (if it have right) lie a whole year to ripen: it will last two, three and four years if it lie cool and close, and endure the drawing to the last drop.” In his notes on brewing ale, Markham said: ” … for the brewing of strong ale, because it is drink of no such long lasting as beer is, therefore you shall brew less quantity at a time thereof …. Now or the mashing and ordering of it in the mash vat, it will not differ anything from that of beer; as for hops, although some use [sic] not to put in any, yet the best brewers thereof will allow to fourteen gallons of ale a good espen [spoon?] full of hops, and no more.”

Markham was writing in the middle of a battle fought for more than two centuries to try to keep ale still free from hops, and separate from hopped beer. In 1471 the “common ale brewers” of Norwich were forbidden from brewing “nowther with hoppes nor gawle” (that is, gale or bog myrtle). In 1483, the ale brewers of London were complaining to the mayor about “sotill and crafty means of foreyns” (not necessarily “foreigners” in the modern sense, but probably people not born in London and thus not freemen of London) who were “bruing of ale within the said Citee” and who were “occupying and puttyng of hoppes and other things in the ale, contrary to the good and holesome manner of bruying of ale of old tyme used.”

Almost 60 years later, in 1542, the physician and former Carthusian monk Andrew Boorde wrote a medical self-help book called A Dyetary of Helth which heavily promoted ale over beer. Boorde, who declared in his book: “I do drinke … no manner of beere made with hopes,” said that “Ale for an Englysshman is a naturall drynke,” while beer was “a naturall drynke for a Dutche man” (by which he meant Germans), but “

of late days … much used in Englande to the detryment of many Englysshe men; specially it kylleth them the which be troubled with the colycke, and the stone, & the strangulion; for the drynke is a cold drynke; yet it doth make a man fat and doth inflate the bely, as it doth appear by the Dutche mens faces & belyes.”

(There is a great story suggesting why Boorde hated beer so much: a rival writer named Barnes said that when Boorde was studying medicine in Montpelier he got so drunk at the house of “a Duche man” [which probably meant a German rather than someone from the Netherlands], presumably on the Dutchman’s hopped beer, that he threw up in his beard just before he fell into bed. Barnes claimed that when Boorde woke up the next morning, the smell under his nose was so bad he had to shave his beard off. For Boorde, the loss of his beard, in a period when a lengthily hirsute chin was the essential badge of every intellectual and scholar, must have been enormously embarrassing.)

A century on, another English writer, John Taylor, in Ale Ale-vated into the Ale-titude, “A Learned Lecture in Praise of Ale”, printed in 1651, agreed that “Beere is a Dutch Boorish Liquor, a thing not knowne in England till of late dayes, an Alien to our Nation till such time as Hops and Heresies came amongst us; it is a sawcy intruder into this Land.” Earlier, a poet called Thomas Randall, who died in 1635, made the same point, in a poem called “The High and Mighty Commendation of a Pot of Good Ale” that

“Beer is a stranger, a Dutch upstart come

Whose credit with us sometimes is but small

But in records of the Empire of Rome

The old Catholic drink is a pot of good ale.”

Shakespeare, being a far subtler writer than Boorde, Taylor or Randall, never made such obvious statements about his preferences. But he was a Warwickshire boy, country-bred, and he brought his country tastes with him to London. In 1630 a pamphleteer called John Grove wrote a piece called “Wine, Ale, Beer and Tobacco Contending for Superiority”, in which the three drinks declared:

Shakespeare, being a far subtler writer than Boorde, Taylor or Randall, never made such obvious statements about his preferences. But he was a Warwickshire boy, country-bred, and he brought his country tastes with him to London. In 1630 a pamphleteer called John Grove wrote a piece called “Wine, Ale, Beer and Tobacco Contending for Superiority”, in which the three drinks declared:

Wine: I, generous wine, am for the Court.

Beer: The City calls for Beer.

Ale: But Ale, bonny Ale, like a lord of the soil, in the Country shall domineer.

Shakespeare’s country-born preference for ale, and disdain for the city’s beer, pops up across his plays. Autolycus, the “snapper-up of unconsidered trifles”, makes his appearance in The Winter’s Tale singing:

The white sheet bleaching on the hedge,

With heigh! the sweet birds, O, how they sing!

Doth set my pugging tooth on edge,

For a quart of ale is a dish for a king.

By which he means that he can steal the sheet someone has left out to bleach in the sun, and exchange it for a quart of excellent ale in a nearby alehouse (which were, alas, sometimes places where stolen goods could easily be disposed of). But if ale is a dish fit for a king, small beer, according to Prince Hal – soon to be a king – in Henry IV, is a “poor creature”, and he asks Poins: “Doth it not show vilely in me to desire small beer?” Similarly the malicious Iago, in Othello, declares that the perfect woman is fit to do nothing more than “suckle fools and chronicle small beer”.

Nor was Shakespeare impressed by strong beer, judging by the fate of the villainous Thomas Horner, the armourer, in Henry VI, written around 1590-92, who is so drunk on sack, charneco (a wine from Portugal) and double beer given to him by his supporters (“Here’s a pot of good double beer, neighbour: drink it and fear not your man”) that his apprentice, Peter Thump, is easily able to overcome him and kill him in their duel.

What was double beer? The 17th century writer William Yworth, in a book called Cerevisiarii Comes or The New and True Art of Brewing, published in London in 1692, said double beer was “the first two worts, used in the place of liquor [water], to mash again on fresh malt”, so that, in theory, the wort ended up twice as strong.

Certainly double beer was strong enough to keep well. Yworth gave a typical 17th-century pseudo-scientific explanation that the double wort “doth … only extract the Sweet, Friendly, Balsamic Qualities” from the fresh malt, “its Hunger being partly satisfied before.” He continued that double beer “being thus brewed … may be transported to the Indies, remaining in its full Goodness … whereas the Single, if not well-brewed especially, soon corrupts, ropes and sours.” (Ropey beer has a bacterial infection which results in sticky “ropes” appearing in the liquid. Note, incidentally, the implication that strong beer was being exported to hot climates even in the 17th century.)

The opposite of doubele beer was single beer. A recipe for 60 barrels of single beer printed by Richard Arnold in 1503, during Henry VII’s reign says: “To brewe beer x. quarters malte. ij. quarters wheet ij. quarters ootes. xl. lb weight of hoppys. To make lx barrell of sengyll beer”, that is, 10 quarters of barley malt, two quarters of wheat and two quarters of oats, plus 40lbs of hops, to make 60 barrels of single beer. It is very unlikely this would have produced a beer of anything less than 1045 OG, or four per cent alcohol by volume. A modern-day brewing to this recipe by the home brew expert Graham Wheeler, using modern yeast, modern malted barley (which would probably have given a higher extract than 16th century brewers could have achieved), malted oats and Shredded Wheat, came out at 1065 OG and 6.7 per cent ABV.

The opposite of doubele beer was single beer. A recipe for 60 barrels of single beer printed by Richard Arnold in 1503, during Henry VII’s reign says: “To brewe beer x. quarters malte. ij. quarters wheet ij. quarters ootes. xl. lb weight of hoppys. To make lx barrell of sengyll beer”, that is, 10 quarters of barley malt, two quarters of wheat and two quarters of oats, plus 40lbs of hops, to make 60 barrels of single beer. It is very unlikely this would have produced a beer of anything less than 1045 OG, or four per cent alcohol by volume. A modern-day brewing to this recipe by the home brew expert Graham Wheeler, using modern yeast, modern malted barley (which would probably have given a higher extract than 16th century brewers could have achieved), malted oats and Shredded Wheat, came out at 1065 OG and 6.7 per cent ABV.

Unfortunately, this guide to the strength of single beer is completely contradicted by a declaration from the authorities in London in 1552, during the reign of Edward VI, regarding the amount of malt that should go into double and single beer. For “doble beare”, they said, a quarter of “grayne” should produce “fowre barrels and one fyrkin” of “goode holesome drynke”. To make single beer, twice as much drink should be brewed from the same quantity of grain. This would have produced double beer with a strength of around 1047 OG at the bottom end, perhaps 1058 at most (barely five per cent ABV), while the single beer could not have been stronger than around 1025 OG, less than two per cent alcohol.

Both these strengths seem far too low – indeed, they seem to use exactly half the malt one might expect, given Arnold’s recipe for single beer, and evidence from other writers. Recipes from the 17th century show beers of around 1035 to 1045 OG being described as “small beer”. Gervase Markham called a beer of approximately 1045 OG “ordinary beere”. Perhaps the London authorities in 1552 were deliberately trying to force the city’s brewers to make weaker beers.

Whatever the case, there is no doubt that Tudor ale was stronger than Tudor beer. Elizabethan commentators believed you could make twice as much beer from a quarter of malt as you could ale, because the hopped beer did not have to be as strong as ale to stop it going sour too quickly. Reynold Scot in 1574 said a bushel of “Mault” would make eight or nine gallons of “indifferent” ale but 18 or 20 gallons of “very good Beere”.

In London in 1574 (when Shakespeare was 10) there were 58 ale breweries and 32 beer breweries. But the ale brewers consumed an average of only 12 quarters of malt a week, while the beer brewers were on average consuming four times as much. The average Elizabethan London beer brewer’s output in pints was thus probably on average eight times larger than the average ale brewer’s production. Even the biggest London ale brewer was smaller, on this calculation, than the smallest of the capital’s common beer brewers. The biggest Elizabethan London beer brewer consumed 90 quarters of malt a week, enough to make around 14,000 barrels of beer a year, very roughly, which would be a medium-sized brewery even in the 18th century.

It is difficult to be precise without knowing what proportion of grain went into single ale and beer, which used less malt per barrel, and what proportion went into double brews. But very roughly, again, it looks as if, even though there were nearly twice as many ale breweries in the capital, Londoners were drinking four times as much beer from the common brewers as they were ale. Some ale and beer would still have been made by alehouse and inn brewers, but their output probably made little difference to the ratio of ale to beer drunk in the capital. When John Grove said in 1630 that “The citie call for Beere”, it looks as if beer was the city of London’s favourite since at least the 1570s.

It was drunk, generally, from hooped wooden mugs: Jack Cade in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, promising his supporters great bounties when he is ruler of England, declared that as well as seven halfpenny loafs for a penny, “the three-hooped pot shall have 10 hoops.” The wealthy used something grander than wood: the Frenchman Estienne Perlin, a visitor to London in the 1550s, wrote that the English drank beer “not in glasses but in earthenware pots with silver handles and covers”.

Many of the beer brewers were still immigrants from the continent. In St Olaph’s parish, Southwark in 1571 there were 14 Dutch brewers. One, Peter van Duran, who had emigrated from Gelderland 40 years earlier, employed nine servants whose nationalities were given as “Hollanders, Cleveners [from Cleves, on the German/Dutch border] or High Dutchmen [that is, Germans]”, and who included a brewer, three draymen, three tunmen and a boatman.

The size of the London brewing industry was causing pollution problems: in 1578 the Company of Brewers wrote trepidatiously to Queen Elizabeth saying that they understood Her Majesty “findeth hersealfe greately greved and anoyed” with the taste and smoke of the sea coal used in their brewhouses. The brewers offered to burn only wood, rather than coal, in the brewhouses closest to the Queen’s home, the Palace of Westminster.

The Queen herself was a considerable brewer: like her father, Henry VIII, she had both a beer brewer, Henry Campion, who died in 1588, and ale brewers, two men called Peert and Yardley. (Campion’s brewery, according to John Stow’s Survey of London in 1602, was in Hay Wharf Lane, at the side of All Hallows the Great church in Upper Thames Street, which puts it on the same site as the Calverts’ later Hour Glass Brewery.)

The Queen herself was a considerable brewer: like her father, Henry VIII, she had both a beer brewer, Henry Campion, who died in 1588, and ale brewers, two men called Peert and Yardley. (Campion’s brewery, according to John Stow’s Survey of London in 1602, was in Hay Wharf Lane, at the side of All Hallows the Great church in Upper Thames Street, which puts it on the same site as the Calverts’ later Hour Glass Brewery.)

Elizabeth also had naval and military brewhouses in operation at Tower Hill, Dover, Portsmouth and, probably, Porchester by 1565, to supply the army and navy. The first royal beer brewery in Portsmouth was built by Henry VII in 1492, and its operations were enlarged by Henry VIII in 1512/13 at a cost of more than £2,600 to enable it to produce more than 500 barrels of beer a day. It seems quite possible this was one of the biggest breweries in the world at that time. But the beer consumption of the Tudor navy was enormous: perhaps 3,000 barrels a week. It was calculated that a ship of 100 tons, carrying 200 men for two months, needed 56 tuns of beer, (that is, around a gallon a man per day, one tun being equivalent to six 36-gallon barrels), 12,200 pounds of biscuit, three tons of “flesh” and three tons of fish and cheese. Water would turn brackish and unhopped ale would go off: beer would last the tour.

The Tudor army certainly ran on beer. In July 1544, during an English invasion of Picardy, the commander of Henry VIII’s forces complained that his army was so short of supplies they had drunk no beer “these last ten days, which is strange for English men to do with so little grudging.” Relief arrived a couple of days later with 400 to 500 tuns of beer from Calais and ten of “the king’s brewhouses” (presumably mobile breweries) together with “English brewers”.

Whatever soldiers liked to drink, Shakespeare’s opinion of the hopped drink was so low, if we can assume he was putting his own thoughts into the mouth of Hamlet, that he could think of nothing more depressing than being used after death to seal the bunghole in a cask of beer. Referring to the practice of using clay as a stopper in a barrel, the gloomy Dane tells his friend:

“To what base uses we may return, Horatio! Why may not imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander till he find it stopping a bunghole? … follow him thither with modesty enough, and likelihood to lead it; as thus: Alexander died, Alexander was buried, Alexander returneth into dust; the dust is earth; of earth we make loam; and why of that loam (whereto he was converted) might they not stop a beer barrel?”

In Two Gentlemen of Verona, however, Launce lists as one of the virtues of the woman that he loves the fact that “she brews good ale”, and tells Speed: “And thereof comes the proverb, ‘Blessing of your heart, you brew good ale.’”

Centuries after his death, Shakespeare was adopted as a trademark by Flowers, the biggest brewer in his home town, Stratford upon Avon. (Flowers was founded, incidentally, by Edward Fordham Flower, who had emigrated to the United States, aged 13, in 1818 with his brewer father Richard. The Flowers settled in southern Illinois, near the Wabash river, on what later became the township of Albion – family legend says they turned down a site further north on the shore of Lake Michigan, believing it to be too marshy. Others were less fussy, and the city of Chicago was eventually founded there. Edward and Richard returned to England in 1824 and Edward began brewing in Stratford in 1831.) Fortunately nobody ever pointed out to Flowers that Shakespeare wouldn’t have liked the hoppy brew they were selling.

(A much shorter version of this piece appeared in Beer Connoisseur magazine in 2009. Other parts have been adapted from Beer: The Story of the Pint, published 2003, with additions

Filed under: Beer, History of beer, Hops

“Fuck” in History

Bringing you only the most important news of the day, here’s the first known use of the word “fuck” in the written English language, in its modern spelling. Written by a monk of course, in 1528.

Opt Out of Standardized Testing

The more parents who opt out of making their children go through the pointless and educationally destructive Common Core standardized testing that is the fad of Rheeist politicians of both parties, the better. I certainly implore all the parents who read this blog to stand up against this horrible education policy that hurts both students and teachers.

[12] Preregistration: Not just for the Empiro-zealots

Interactive map of the drug war in Mexico - 2012

It's that time of the year again when I update the interactive map of the drug war in Mexico. The map now uses 30 day months to calculate homicide rates and the new CONAPO population estimates. As usual there is also a Spanish version. All deaths registered without a date of occurrence were assumed to have occurred in the same month they were registered and all deaths without a municipio of occurrence were assumed to have taken place where they were registered. Various events are worth checking out:

- Zacatecas/Fresnillo

- The increase in violence in Nuevo Laredo, which proved to be much worse than thought

- San Fernando

- The Michoacán/Jalisco border (where a mass grave with over 60 bodies was recently found)

- Western border vs Eastern border

- More bodies from the Durango mass graves that apparently were not reported

- Homicides for the whole sexenio

I again classified all deaths of unknown intent into accidents, suicides and homicides based on the age, sex of the victim and injury mechanism by which the death occurred. The method I used is similar to the one I used in my Juarez post (with a penalized regression for Sinaloa and knn for the rest of Mexico). For example, if someone told you to guess the intent of the death of a 70 year old woman who died in Merida by motor vehicle, you'd probably guess it was an accident. If you had to guess the intent of the death of a young male in Acapulco who died by firearm, you'd probably think it was an homicide.

The problems with the data in the Federal District and Sinaloa were also corrected.

Since firearm accidents in Baja California went from 6 in 2006 to a 100 in 2007 and again to 6 in 2008 I reclassified all firearm accidents as if their intent were unknown in 2007.

I also added the mass grave in Taxco and the one in San Fernando since they either don't appear or are incomplete in the dataset from the INEGI.

P.S. You can download a csv with the data from the projects page

A-B InBev, Heineken battle it out for Mexican beer business (video)

There’s big money in beer brewing, and in Mexico, two major companies are competing for the bigger share of that market.

More >> KSDK.

Denver may see 20+ breweries open this year

There were 23 breweries inside Denver’s city limits at the start of 2013 (depending on how you count them), and by December 21, when Station 26 opened in North Park Hill, there were 29 (again, depending on how you count them).

More >> Cafe Society.

Archeologists Discover Ancient Brewer’s Tomb In Egypt

[[Click through to the Bulletin for full content]]

Worldwide Alcohol Consumption Cartogram

Jim.PavlikBeer and maps! What's not to like??! Gall-Peters Debate!!! Oh Yeah!

[[Click through to the Bulletin for full content]]

Sandfall

A rather beautiful new piece of technology from, appropriately, Sandia.

Source: photoree.com

Concentrating thermal solar power – CSP or CST – has been the perpetual bridesmaid to solar PV. Just as it´s about to go commercial, the price of solar PV drops again and the projects are shelved. CSP is growing, but at a fraction of PV´s headlong pace. Brightsource, the leading commercial player in the US, only predicts the global market to reach 30 GW by 2020. (One prediction for PV at the same date is 330 GW.) CSP has one big thing going for it: storage. As you start with a hot fluid, it´s fairly easy to add a thermal heat reservoir at the point of production, The Spanish company Gemasolar has demonstrated 24-hour electricity generation with hot salt storage coupled to a solar tower. The Australian grid operator AEMO reckons that this isn´t optimal, as there´s very little demand for electricity at 3 am, and 9 hours of storage will get you comfortably through the dark evening (pdf report, Appendix 2). Still, a 9-hour Gemasolar clone remains expensive.

The likeliest way to bring costs down is to go hotter. Currently operational CSP plants use water/steam as the working fluid, and standard Rankine-cycle steam generators. The PS10 solar power tower near Seville, the largest currently operational, has a steam working temperature of only 275 deg C at the receiver outlet. Brightsource´s Ivanpah tower in California, the largest under construction, will run hotter at 560 deg C.

The Rankine cycle isn´t very efficient. Most current steam generators are at 35-42%. This is a very mature technology and it´s very hard to improve on it, especially with relatively small 100MW rigs. To push up efficiency, the favoured way is to go hotter. Partly because of the basic physics of heat engines; partly because above 800 deg C or so you can switch to or add a Brayton cycle, aka a gas turbine. Feed the still hot gas turbine exhaust into a conventional steam generator, and you have a combined-cycle generator plant. These are routinely used in natural gas plants and regularly achieve efficiencies over 60%.

A solar tower can easily reach such temperatures at the focal point. Large research parabolic solar furnaces get over 3,500 deg C. Long before the theoretical limit of 6,000 deg – the temperature of the Sun´s surface – you would run out of materials to hold targets in, and you are left with a fun but completely useless fixed death ray. The problem is capturing the heat with a non-magical material and transferring it to your heat engine.

One candidate is an alveolated ceramic block fixed in the receiver, with blown air as the working fluid. The EU went into this in the last decade but the scheme hasn´t made it into precommercial pilots. I suspect the problem isn´t the ceramic but the air: perhaps it´s not dense enough to support high rates of heat transfer.

Enter Sandia with a different idea: grind the (EU´s?) refractory ceramic into sand and use a sand-air mixture as the working fluid. Capturing the heat is beautifully simple: the sand just falls in a curtain past the receiver window and is heated up to 1000 deg C. It is collected at the bottom of the tower in a heat exchanger which feeds air or steam into the turbine. The sand has a lot of thermal inertia so it could be its own storage, depending on cost. The working fluid´s higher temperature and density translates to a more compact and efficient plant with – they hope – a much lower cost of generation.

This photo shows a demonstration receiver. Clearly this is still an early-day lab rig. The aim is a complete operational design by 2017, and they still have to overcome a host of problems, including machinery (pumps, bucket elevators) that will survive a diet of red-hot abrasives. More sketches here. Via CleanTechnica.

This photo shows a demonstration receiver. Clearly this is still an early-day lab rig. The aim is a complete operational design by 2017, and they still have to overcome a host of problems, including machinery (pumps, bucket elevators) that will survive a diet of red-hot abrasives. More sketches here. Via CleanTechnica.

Still, it´s very pretty idea. Gravity is as cheap and reliable a way of moving stuff around as you can possibly get. Give them more money!

******************************

Is it frivolous to judge technological innovations on aesthetic grounds, as I´m doing here? It would be to make it the only criterion. But form follows function. The human aesthetic response is surely part of Daniel Kahneman´s automatic, instinctive, efficient mental System 1, even if it´s educated by conscious learning and reflection. The ev-psych argument that it´s partly based on utility is very strong. Beautiful people have the characteristics of biologically good reproductive partners. Beautiful landscapes of the Arcadian type correspond to good environments for hunter-gatherers. It´s not a stretch that this extends to artefacts as well as images: a beautiful house is one you would like to live in, an iPhone is a tool you enjoy using. So our aesthetic reaponse to engineering reflects an instinctive judgement that it´s fit on a range of practical dimensions: transparent, controllable, economical, compact, stable, reliable.

Of course the aesthetic reponse has other triggers than fitness for use. We are also attracted to environments – mountains, storms, deserts of sand and snow – that are extremely hostile; animals like tigers and dinosaurs that are (or would be) very dangerous; and representations of violence and terror in tragedies and action movies, embedded and distanced in a moral narrative. Why this should be so is a puzzle. Aristotle´s theory of catharsis about the last category look fishy, but I don´t know of a better one. The Romantics distinguished between the Sublime (the Alps, Gothic cathedrals, King Lear) and the Beautiful (girls, flowers, songs). There´s something in this, but as far as I can tell the subjective sensation is the same. Maybe there´s a connection with the paradoxes of sexual selection: features like the peacock´s tail or behaviour like the pronking of gazelles that are worse than useless, but demonstrate to potential mates a male´s superior fitness as obstacles he has successfully overcome. (Sexual selection is not gender-neutral.) Perhaps we admire Gothic cathedrals because of the sheer crazy prowess of building such unnecessarily tall and airy structures out of stone and weak mortar. In any case it doesn´t look as if my aesthetic response to the sand CSP concept is driven by any of these factors.

Early-stage R&D is necessarily based on inadequate information. It´s likely to fail. The decision to fund or not is a poker bet based on the few cards in your hand. It´s sound to pay attention to your instincts as well as your reason – though as information accumulates during the game or project, reason should exert greater control. The aesthetic response is one such input from instinct. So don´t believe in the beautiful idea as Dirac advised – but do give it a chance.

There is a second, unrelated argument for making and publishing an aesthetic judgement. Most R&D projects fail. Indeed most human projects of any ambition do too: most scientific papers and novels are unread, most films are scarcely watched, most competitors in a sporting or electoral competition lose. But while generally failing, we can all still occasionally achieve good work. The relegated football team can score a fine goal in a match it loses. I suggest that it´s therefore a social and cultural duty to praise areté wherever we see it. Success, which is often due to luck, is a very crude and misleading proxy for excellence.

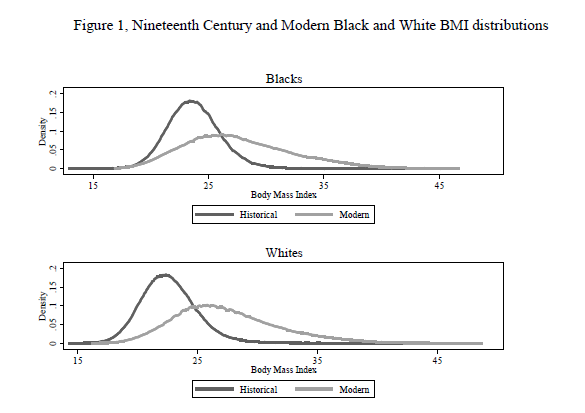

Average is Over

There has been an increase in the mean body-mass index since the 19th century but even more strikingly there has been an increase in the variance, what we might call an increase in weight inequality. More here.

Hat tip: Andrew Leigh.

Average Is Over—if We Want It to Be

Tyler Cowen's new book Average Is Over makes an excellent followup to his previous work The Great Stagnation and I expect it will set the intellectual agenda in much the way that its predecessor did. I want to offer not so much a review as an effort at explication, because I feel like a lot of Cowen's recent work has taken a somewhat cryptic tone for strategic or commercial reasons that are a little bit beyond me.

In Stagnation, Cowen reviewed the previous generation and concluded that despite substantial progress and catch-up in poor countries that the median household in rich countries had suffered stagnant living standards thanks to a slowdown in technological progress. In Average, Cowen looks ahead at the next generation and concludes that despite substantial progress and catch-up in poor countries, the median household in rich countries will suffer stagnant living standards thanks to a speedup in technological progress.

Curious. Which is to say that while each book offers a brilliant exposition of income stagnation and how it intersects with the technological progress of its era, read in conjunction it's clear that in neither period was the stagnation actually caused by the pace of technological change.

And scratch the surface and you'll see that Cowen actually thinks there's a policy reform agenda that, if implemented in a timely fashion, would channel much more of the gains of future automation and computerization to the median household. The agenda is, roughly:

— Liberalization of intellectual property law.

— Liberalization of zoning codes and building restrictions.

— A reformed and somewhat more generous welfare state focused on basic income and wage subsidies.

— Monetary policy that puts greater weight on the labor market fate of young workers and less on the fate of old asset owners.

— A continuation of recent education policy trends that are supportive of greater use of digital technology and outcomes-based meaures.

— Some kind of Sinagporeanization of health care payments, plus supply-side reforms in terms of licensing and so forth.

— Opener borders and freer movement of people.

It's a nice agenda if you ask me. I'm more enthusiastic about monetary policy and less enthusiastic about health care stuff than he is, and I'd also throw in enthusiastic support for preschool stuff that he's skeptical of. But in general a very solid forward-thinking 21st century egalitarian agenda. The reason Cowen focuses more on the somewhat dour outlook for the median household than on these possible solutions to the problem is that he doubts the political system will deliver any of these solutions. He notes that none of them are particularly on the partisan agenda of either political party, that the nature of the U.S. political system makes large changes generally unlikely, that an aging population is less likely to embrace radical changes, and that elites have a lot of ways of reenforcing their control over the political process.

That seems like a reasonable forecast to me. But it's a very different forecast from the forecast that automation and the rise of the machines means that "average is over." The actual forecast is that the political system will be under the control of a relatively narrow elite who will stomp on the interests of the median household.

So I would take the message to be something like "politics is really important just as it always has been and people ought to get more fired up about some ideas that aren't at the current forefront of the congressional agenda." Cowen's actual message seems to be that we ought to make ourselves more complacent, and that these somewhat bleak trends he forecasts aren't really all that bad if you look at them in the right light. But I don't quite see why. If good public policy were easy, there wouldn't be so much poverty and misery in the world. But if good public policy were impossible, there wouldn't be any success stories and "growth miracles" and "trente glorieuses" and so forth.

Why not try? Average is only over if we want it to be over. And I don't!

Map of the World's Most Popular Websites

Cool map from Pew shows the most popular website in each country, weighted by size of internet population.

Google dominates the developed world, but the developing world is very scattered between Google countries and Facebook countries. It looks a little like a map of cold war proxy wars. But the real cold war is between the Google zone and then the vast Chinese market which is dominated by a local company that's friendlier to Chinese censorship efforts. When Farhad Manjoo and I did our Apple/Google war games, this was a key point—Google seems ubiquitous and fully necessary, and then you realize there's a whole giant country where there basically is no Google.

.png)