I often feel like I have Oscar the Truth Toad sitting on my head. Painting by Travis Louie.

Shared posts

Content, Cats & a Site Update

A.Nfor the cat pictures.

Hi! Hi hi hi.

How are you? I am fine. Everything is fine. Very very busy with non-blog work and then we had to travel to New York for a family wedding on Saturday and oh, absolutely, the whole thing started out as a planned day trip and ended up being a complete and utter clusterfuck as per my usual travel exploits, and while I suppose it would make for a classic Idiots Doing Idiot things story, the real reason things unraveled on us as badly as they did obviously kills the potential/appropriateness of humor. Long story short: Getting out of Manhattan and onto the very last NJ Transit train of the night was no easy feat on Saturday, and involved several unnecessary and/or aborted Uber rides, a lost credit card, a frantic sprint on and off the subway and a lot of REALLY oblivious, slow-moving Mets fans.

None of it was very fun, but we made it home and the wedding was just lovely.

(We also finally took some pictures of us together!)

Another reason for the relative silence here on the blog is that FINALLY, in the year of our Lord 2016, I am redesigning the fucking thing. I promise to keep the overall change fairly minimal, but it's obviously time to make the site responsive/mobile friendly and freshen up the layout and fonts. My four-year-old self will still be here to scream at you, just from the top of the site so I can stop wasting

so much

damn space

over

there.

<--------------

Currently working on some ad zone kinks and settling on final fonts (VOTE NOW SERIF OR SANS SERIF IN COMMENTS THIS IS MIGHTILY IMPORTANT), but other than that, you can go ahead and Expect That Shit at some point very soon.

In the meantime, please to enjoy some photos about the True Cost of a Forever Home from a very patient rescue cat's perspective:

HALP

Judge's Football Team Loses, Juvenile Sentences Go Up

Kids who are sentenced by college-football-loving judges who are disappointed after unexpected team losses are finding themselves behind bars for longer than kids who are sentenced after wins or predicted losses.

That’s the gist of a new working paper by a pair of economists at Louisiana State University. It sounds almost comical, like an Onion headline, at first glance: “Judge Sentences Teen to Two Years After Louisiana Tigers Fall to Wisconsin Badgers.” But, insists Naci Mocan, an economics professor at LSU and a co-author (with a fellow professor, Ozkan Eren) of “Emotional Judges and Unlucky Juveniles,” it’s not far off.

In looking at decisions handed down by judges in Louisiana’s juvenile courts between 1996 and 2012, the pair found that when LSU lost football games it was expected to win, judges—specifically those who had earned their bachelor’s degrees from the school—issued harsher sentences in the week following the loss. When the team was ranked in the top 10 before the losing game, kids wound up behind bars for about two months longer, on average. When the team was not as highly ranked, it was a little more than a month. The pair found that the harsher sentences disproportionately affected black defendants.

Judges are supposed to operate without bias and without letting their emotions influence how they make decisions. They are also human. And the idea that emotions in one realm shape decisions in another is not new. The stock market does better when the sun is shining, for instance. But the stakes, particularly for young people of color, are high.

The authors looked specifically at first-time offenders between the ages of 10 and 17 who were convicted of a single statute offense, like drug use or robbery, to “circumvent any potential confounding effects.” They excluded first- and second-degree murder and aggravated rape because those cases require mandatory sentences in Louisiana, and ultimately looked at about 8,200 records involving 207 judges.

Mocan and Eren found that the behavior of the children in court wasn’t a factor in sentencing. Economic background didn’t seem to play a role either. Cases are randomly assigned by a computer in Louisiana juvenile court, so judge selection wasn’t an issue. And a placebo test showed that non-LSU games didn’t have an impact.

The research is obviously limited in scope, and the authors looked at a state where football culture runs deep. It’s unclear whether judges in, say, California, would hand down longer sentences after a University of Southern California loss. Jeffrey Butts, the director of the Research and Evaluation Center at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, said the study seemed like “academic clickbait.” What are judges supposed to do, he asked rhetorically, not handle cases in the week following each unexpected loss?

Butts is open to good data analysis, he said, and appreciates transparency, but he has concerns about what he sees as a movement toward using large data sets for things like predictive policing, where police use math and data analysis to pinpoint potential criminal activity. That may be acceptable as long as it’s one tool in many, he said, but data shouldn’t drive the entire justice system.

Where some might argue relying on data would eliminate human bias, Butts worries it would reinforce and hide bias. Consider, he said, a 16-year-old drug user who lives in a neighborhood where everyone has a car and a rec room or a basement where neighborhood kids gather to smoke or shoot up or whatever. Those kids are going from private space to private space, so the chances of being seen by a cop and arrested are low. Now consider a 16-year-old drug user who lives in a two-room apartment where no one has cars. He and his friends wind up taking a bus or walking to a local park or alleyway, where the chances of being arrested are high. That second kid might get picked up more often, which might mean increasingly tough sentences. A human might be more aware of the context in which the kids are committing the crimes, Butts said, where an algorithm might fail.

But Mocan hopes the research will strengthen what he says is a growing body of evidence that suggests emotions influence unrelated decisions. He hopes, too, that the more judges know about the impact of emotional shocks (in this case, football losses), the more aware they’ll be of their own decisionmaking. “Maybe they will be careful,” he said.

Mocan and his colleague started looking at the impact of football scores after studying how judges react to news coverage and local crimes. As they were contemplating how judicial decisions are affected by judges’ exposure to different communities, they wondered whether football might also be a factor. “Frankly, in the beginning, we thought we wouldn’t find anything and that it was probably a waste of time,” Mocan said. “But, in fact, we found robust and significant relationships.”

Marc Schindler, the executive director of the Justice Policy Institute and a former public defender in Baltimore, said he found the study fascinating. While he’s not convinced judges will take it to heart, he said defenders might see the study as a tool. If he was defending a kid in Louisiana in the week after a big LSU upset and knew the judge had attended the school, he might say something like, “Now, Your Honor, I know we all had a rough day on Saturday, but we all know we’re not going to let that impact our decision making…” Maybe it would backfire, but maybe it wouldn’t.

Schindler wants to know how unique the results are, but, broadly, he thinks the paper could bring renewed attention to the fact that adult behavior or emotion, such as anger at a kid’s attitude in court, can drive decisions in juvenile court where kids’ actions are what should matter most. “We shouldn’t lock kids up because they make us mad,” he said. In an ideal world, he added, everyone dealing with children in the juvenile-justice system should be trained in adolescent development and also be aware of their own biases, racial and otherwise.

While the paper is relatively small in scale, perhaps it will spark a broader conversation and more research. “This is not a little lab experiment,” Mocan said. “These are consequential decisions made by uniformly highly educated people.”

You Can Pinch to Zoom in Instagram Now

It’s always been one of the most annoying parts of Instagram: If you really liked a friend’s photo, and wanted to get up close to inspect it… you could’t. There was no way to zoom in on a photo.

Instagram has now relieved us of that error. Starting Wednesday, iOS users will be able to pinch to zoom in on Instagram photos and videos. Android users will be able to zoom in a few weeks, says the company.

“As things change, we’re still focused on improving the core parts of Instagram,” says a release from the company.

Instagram has put its app through a number of changes in the past year, most significantly adding a rolling “Stories” feature earlier this month. Many of these changes were undertaken to fend off its biggest rival, Snapchat, which has become increasingly popular among teenagers. Wednesday’s update seems to demonstrate that the app is looking for any way to improve its core services without undermining the simplicity that made it famous.

Girls Feel Stranger Things, Too

As an eleven-year old-girl growing up in the 1980s, I was sure I was some variety of previously unclassified monster. I had a million words at my command, but still couldn’t make adults understand me. I stared in the mirror wondering if I was pretty and good, and also wondering why I cared. I felt, in other words, like a “weirdo”—but I wasn’t. This was the completely average experience of an eleven-year-old girl in the Reagan-era suburbs. But it was an experience I rarely saw reflected back to me in the movies I watched — despite the fact that the 1980s were supposedly a golden era of movies for young people.

Into this gap moves Netflix’s Stranger Things. As countless commentators have noted, the show offers a very smart brand of nostalgia: the kind that, instead of mocking or aping an earlier era, makes you long for a time you didn’t realize you were missing. Some of this feeling, of course, is screen memories: Stranger Things feels like the 80s because it mimics so accurately the movies we watched in our youth—all of those Spielberg, Carpenter, and Hughes films, not to mention myriad adaptations of Stephen King. But at the same time, in a way that few if any critics have pointed out, it repairs a gaping hole at the center of those movies: their inability, in films all about the wonders of childhood, to imagine the inner lives of girls.

Take The Goonies, for instance, a movie lovingly invoked by Stranger Things, not only in its detailed portrayal of pre-adolescent friendships but in its deft attention to class. There are exactly two girls in The Goonies: Andy, a cheerleader so intent on making out with a particular boy that she ends up accidentally snogging his younger brother, and Stef, a tomboy who spends most of the movie rolling her eyes and audibly scoffing. Andy and Stef are girls defined through and against boys: Andy is boy-crazy, and Stef desperately wants to be a boy.

Take The Goonies, for instance, a movie lovingly invoked by Stranger Things, not only in its detailed portrayal of pre-adolescent friendships but in its deft attention to class. There are exactly two girls in The Goonies: Andy, a cheerleader so intent on making out with a particular boy that she ends up accidentally snogging his younger brother, and Stef, a tomboy who spends most of the movie rolling her eyes and audibly scoffing. Andy and Stef are girls defined through and against boys: Andy is boy-crazy, and Stef desperately wants to be a boy.

As portrayals of 80s kidhood went, E.T. was a bit better; there was so little that was aggressively boylike about Elliot. But while his sensitive outsiderhood invited girlish empathy, his disgust at E.T. in Gertie’s dress-up clothes was a slap. John Hughes’s movies, those cherished staples of 80s adolescence, also offered little; neither Sixteen Candles’s Samantha nor Pretty in Pink’s Andie was particularly complex. (And the fact that two of the most iconic 80s teen girls are named Andy should tell you something about how 80s movies felt about girlhood.) Though Molly Ringwald’s soulful stares and barely-concealed disgust made her a model of seething teenage angst, even those films still defined their female characters primarily in terms of their relationships with men.

Stranger Things, to my relief and delight, tweaks these sources and others to create female characters who aren’t just props in boys’ stories. When Nancy and Barb first appear in Stranger Things, they look like Andy and Stef: Nancy is all aflutter about her budding relationship with school jock Steve; Barb, in her choking flowered top and mom jeans, seems to be actively warding off male sexual interest. A lesser show—an 80s show—would have made Nancy’s arc all about her encounter with Steve; an 80s horror movie would have killed her for it. But for Stranger Things, Nancy’s choice to sleep with Steve is a minor aspect of her character, defined primarily by her development into a “badass.” Barb’s mental inventory of Nancy’s underwear, meanwhile, hints at a possible attraction without turning Barb’s sexuality into an object of ridicule. If she’s a lesbian, she’s neither monstrous nor man-hating, nor is she trying, like Stef, to shed her loathsome girlness.

Stranger Things, to my relief and delight, tweaks these sources and others to create female characters who aren’t just props in boys’ stories. When Nancy and Barb first appear in Stranger Things, they look like Andy and Stef: Nancy is all aflutter about her budding relationship with school jock Steve; Barb, in her choking flowered top and mom jeans, seems to be actively warding off male sexual interest. A lesser show—an 80s show—would have made Nancy’s arc all about her encounter with Steve; an 80s horror movie would have killed her for it. But for Stranger Things, Nancy’s choice to sleep with Steve is a minor aspect of her character, defined primarily by her development into a “badass.” Barb’s mental inventory of Nancy’s underwear, meanwhile, hints at a possible attraction without turning Barb’s sexuality into an object of ridicule. If she’s a lesbian, she’s neither monstrous nor man-hating, nor is she trying, like Stef, to shed her loathsome girlness.

Even more than Nancy and Barb, Eleven redeems, retroactively, all of the disappointment of being a girl in the 1980s watching beautifully rendered portrayals of (pre-)adolescent life that cared only for boys or, at most, boys as seen through the eyes of girls. She embodies how terrible and wonderful and frightening and overwhelming and fun and sad it was to be an eleven-year-old girl during the waning years of the Cold War. I, unlike Eleven, had more vocabulary than “yes” and “no” and was well versed in the roller coaster joys of the La-Z-Boy. But her alienation is completely familiar.

The most compelling aspect of Eleven’s character is how terrified she is by her own feelings. Raise your hand if you would have flipped a van for your sixth-grade crush. Mine was Eric Berg, and I would have done it in a heartbeat. And then I would have been horrified by my own strength. “What is WRONG with you?” Mike demands to know when Eleven hurls Lucas against a wall to stop him punching Mike. What’s wrong is how much she feels: so much she can tear through water with her screams, so much she can open a gate to another dimension.

Adolescent girls have long been taught that our feelings—particularly our new and confusing feelings about boys (or girls, as the case may be)—are the most dangerous thing on earth. To put it in terms that Avidly readers understand: Jo gets mad, so Amy drowns. Emotions kill. Stranger Things doesn’t deny this; it literalizes it, then reminds us that emotions also save and heal. To my pre-adolescent self, Eleven would have been a revelation: a strange girl whose friends (even, eventually, Lucas) accept her as just another kind of weirdo, whose worthiness doesn’t depend on her performance of femininity, whose power is protective and not just destructive.

Fortunately, those of us who grew up in the 80s also experienced the 90s, where Dana Scully and Buffy Summers awaited us. But with its flawlessly staged setting and piled-up homages to 80s movies, Stranger Things has performed a kind of time travel: it has reached back into my memories, Total Recall-like, and inserted characters who now seem as though they were there all along. Nancy, the nerd-turned-monster killer who can like more than one boy at once. Barb, the buttoned-up babygay whose best friend won’t let her be disposable. Eleven, the terrifying, funny, scared, brave, smart weirdo whose feelings could save the world.

Ashley Reed: Timeless 80s icon.

The Bizarre Words of Donald Trump’s Doctor

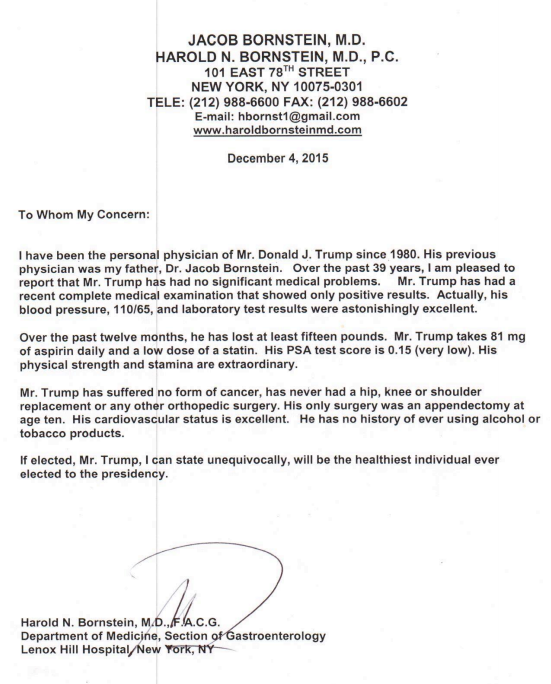

Cameras rolling, Manhattan gastroenterologist Harold Bornstein was confronted last week with a letter that carried his signature. In that letter, the writer “state[d] unequivocally” that Donald Trump “will be the healthiest individual ever elected to the presidency.”

Donald Trump would be the oldest individual ever elected to the presidency. He sleeps little and holds angry grudges. He purports to eat KFC and girthy slabs of red meat, and his physique doesn’t suggest any inconsistency in this. His health might be fine, but a claim to anything superlative feels off.

Bornstein might have jumped on that opportunity to get out of this mess—to say that Trump had dictated the letter, and Bornstein only signed it. Or that Trump had at least suggested phrases. Because it’s not just the facts of Trump’s life that don’t add up, but the linguistics of the letter.

To readers with a keen eye, the hand of Trump might seem evident, particularly the descriptors: “his strength and physical stamina are extraordinary” and his “laboratory test results are astonishingly excellent.” There is even an instance of the Trumpian habit of beginning a sentence with “actually,” for purposes of building on (as opposed to contradicting) the prior sentence: “Mr. Trump has had a complete medical examination that showed only positive results. Actually, his blood pressure and lab results were astonishingly excellent.”

EXCLUSIVE: Trump doctor says he wrote health letter in just 5 minutes as limo waited https://t.co/hy9CLowPJt pic.twitter.com/CyoqDpVhIl

— NBC Nightly News (@NBCNightlyNews) August 26, 2016

But Bornstein only stuck to his guns. Not only did he double down on the letter, he said he rather liked the line about Trump being the healthiest person ever elected president. So I’d like to go through this letter a little more closely.

The adjectives are the most obvious clue. Doctors describe lab results as “normal” or “within normal limits.” If in some rare case these results warranted qualitative assessment, “reassuring” or “encouraging” would be more likely than “excellent.” Were it ever warranted to choose “excellent” as the qualifier, the effect would never need heightening with an adverb like “astonishingly.”

Especially to describe normal lab tests. Many doctors do experience astonishment, but we are trained to keep medical documentation within a regimented, almost militant set of rhetorical boundaries. That serves a couple purposes, primarily to limit subjectivity. During my medical internship, I had a patient who was taking blood thinners, and she came to the hospital after she had accidentally taken too much. Our plan was to keep a close eye on her until the medication wore off. I wrote in the patient’s chart, in one hurried stroke, that the action plan was to discharge her from the hospital as soon as her blood coagulation rates were “cool.”

I received an irate page from my attending physician as soon as he read that. “WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR A TEST TO BE COOL?”

Point taken, I was supposed to write “when the INR [international normalized ratio] is between 2 and 3.” This way there would be no ambiguity for anyone who reads that chart. He knew what I meant, but his point was that every nurse and social worker and phlebotomist (and lawyer) who picked up that chart needed to be on the same page. So always write this way.

One key place where he does use the right language—“positive results”—he’s using it a way that would be nonsense in clinical parlance. We would say that a test had a positive result, for example, if an HIV assay detected the presence of a virus. Negative results would mean no HIV. Bornstein writes that Trump’s “medical examination showed only positive results.”

Again, in everyday conversation, people would know what that means. Over years of medical training and practice—decades in the case of Bornstein—the instinct to write in a colloquial way is washed out of you. Whether qualitative hyperbole and superlatives would often be of any use in a doctor’s assessment is moot, because they are simply not part of the lexicon. If a physician were going to break from that lexicon, it would not be in a career-defining document when the task is predicated on conveying credibility and authority.

So for linguistic reasons alone, it would shock me if Bornstein wrote this letter. Add to that the other bizarre elements, and it was jarring to hear him stand by it last week, laughing in the process. In video footage that appears to have been taken covertly, Bernstein also admitted that he “wrote the letter in five minutes” while a car was idling outside waiting for him. This is a critical fact: It means that he cowed to the demands of his patient. (Trump had tweeted two days prior, “I have instructed my long-time doctor to issue, within two weeks, a full medical report—it will show perfection.”)

Patients don’t instruct doctors. Bernstein didn’t admit to taking instruction or dictation from Trump, or to signing a prewritten letter, but he did admit last week to throwing together a haphazard letter under unreasonable time constraints so as not to keep the idling car waiting. The letter is dated December 4, and Trump tweeted his promise on December 3. The two-week deadline was nowhere near. The writing could’ve waited another hour. If the car was in such a hurry, Bornstien could’ve emailed it later that afternoon.

And Bornstein does use email, as we know from the letterhead, which includes “E-mail: hornist@gmail.com.” That is another oddity. Gmail isn’t a secure platform, so it’s not meant for patients to communicate medical information. And that is why you’d be communicating with a doctor in the professional sense. This isn’t just for fear of google being hacked; it’s the law (HIPAA).

(A quibble from an editor: Is writing “E-mail:” necessary? If you saw simply “hbornst1@gmail.com,” would you think, “What is that?”)

Another physician, Jennifer Gunter, an obstetrician-gynecologist and “sexologist,” made similar observations recently in an article for The Huffington Post titled "I’m A Doctor. Here’s What I Find Most Concerning About Trump’s Medical Letter.” (That made me want to start every headline with “I’m a Doctor.”)

What she found most concerning was ... many things. Among them, Bornstein’s signature line says that he is part of the “section of gastroenterology” at Lennox Hill hospital. He is not. And only partly because there is no section of gastroenterology at Lennox Hill hospital. There is a gastroenterology division. And he is not part of that, either.

It may just be that the footer is outdated. And also the header, as it includes two names: Harold Bornstein and Jacob Bornstein. The latter is deceased. He died not recently, but in 2010. That leaves plenty of time to remove his name from the letterhead.

The letterhead also includes a web address, haroldbornsteinmd.com. I visited immediately when I first read the letter. It was a nonfunctioning site. (And now I see that the URL redirects to a site that sells prank teddy bears, of the sort that sing “Happy Birthday” when squeezed, for three solid hours.)

These are all small things in isolation, but together the evidence suggests that this letter was written at a time distinct from the dating of the letterhead and signature, which are seriously outdated. The letter also does not appear to be written by a physician. It does appear to have been written by someone who speaks like Donald Trump.

If Bornstein is the author of these words, and they were written under the circumstances he described on Friday (in five minutes while the limo idled outside), then not only is Bernstein not a meticulous physician, but he has shown that he will compromise professional standards in order to do what Trump asks of him.

So, is Trump in good health? There is no legal requirement mandating transparency in that regard. With the bizarre letter before us, he has not been transparent. That may be the best that can be said. I’m less concerned with his health than his character.

Last week Bornstein laughed when he mentioned Trump’s mental health: “His mental health is excellent. He thinks he’s the best.”

I caught some criticism recently for suggesting that Trump is—as the man’s own ghost-autobiographer described him— “a sociopath.” I was careful not to give him an actual medical diagnosis. Sociopath is a colloquial term for something in the venn diagram between antisocial and narcissistic personality disorders. I thought it was a worthwhile exercise to go through the diagnostic criteria and think about them. The dean of Harvard Medical School, for one, agreed. He said that, at least in this circumstance, more physicians should be speaking out.

Normally it’s inappropriate for physicians to weigh in on patients they haven’t seen personally. Out of respect for the process of diagnosis, some physicians are deferring to Bornstein. What would it take for more in the medical community to break the code and say that this man’s appraisal is inadequate?

Even the reserved CNN correspondent Sanjay Gupta spoke out last week: “I don’t even know what to make of this letter.” That is the Gupta equivalent of spitting fire. “It's just a strange letter that's absurd.”

Bornstein has not replied to request for comment. (I wrote to him at the email address on the letterhead, which might be his actual email address.)

The students are back in town, surviving off happy hour specials...

The students are back in town, surviving off happy hour specials and scavenging the street for free furniture. They come from all corners of the world to savor the excitement of Washington DC. In a few short years most will be gone, but some will stay in a slow evolution from dorm to English basement to shared rowhouse, eventually scattering to the furthest ends of the metro line.

Georgetown’s Old Stone House on 3051 M Street NW has seen it all. Built in 1765, it is Washington’s oldest standing house. If the bricks could speak, what stories would it tell of the generations that have passed by, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, about to begin this next chapter of their lives?

—

*Postcards from Washington DC is a personal challenge to produce a weekly illustration that highlights life in the capital.

—

This week you will be able to buy postcards at Maketto’s vending machines. Follow the guys of Guerilla Vending for more details.

Wind

Don’t we all feel like this guy at times? Beautiful etching by Valdas Misevičius.

That’s how it’s done, bitches. Apparently.

Dog Illustration by Faye Moorhouse

Dog art that’s cute or classically “beautiful” is certainly great (we feature a ton of it right here on this blog), but I think there’s something maybe a little extra special about art that manages to capture the imperfect nature of our canine friends — after all, so much of what makes dogs so endearing, I think, is their (very human-like) imperfect-ness. It’s why the illustrations of Faye Moorhouse speak so strongly to me. The dogs Moorhouse depicts are generally not conventionally “cute” or “beautiful” — Moorhouse herself calls them “hideous” and “wonky” — and yet despite the abstraction of Moorhouse’s illustrations, her dogs somehow seem so much more real. Check out Moorhouse’s work on her website, Tumblr (including her project Dogs A-Z), and Instagram, and find prints over at her Etsy shop.

[Found via Four & Sons]

Share This: Twitter | Facebook | Don't forget that you can follow Dog Milk on Twitter and Facebook.

© 2016 Dog Milk | Posted by Katherine in Other | Permalink | No comments

It Shouldn't Have Taken a Khizr Khan

I’ve found the Khizr Khan vs. Donald Trump clash exhilarating. It’s the closest thing Americans have yet seen to the famed “Have you no sense of decency, sir,” riposte that helped doomed Joseph McCarthy. But it’s disturbing, too. If it proves that America can overcome the bigotry and ignorance that Trump represents, it also shows how much Trump has already set America back.

Start with the Democratic Party’s decision to feature Khan at its convention in the first place. The Clinton campaign understandably wanted to showcase someone who could rebut Trump’s slander that Muslims cheered 9/11 and should be temporarily banned from the United States. And in the story of Captain Humayun Khan, and the figure of his father and mother, the party had a potent counter-narrative. The problem is that in choosing a family that had displayed such extraordinary patriotism and sacrifice, Democrats sent the implicit message that Muslims must show extraordinary patriotism and sacrifice in order to deserve the same rights and respect as everyone else. The Democratic Party, after all, did not require that the African American, Latino, female and LGBT speakers at the Wells Fargo Center earn their right to demand equal protection of law by losing a child.

For all his eloquence and dignity, Khizr Khan himself accentuated this double standard when, in the opening sentence of his speech, he described himself and his wife as “patriotic American Muslims—with undivided loyalty to our country.” (Earlier in the week, Bill Clinton had said something similar, declaring that, “If you’re a Muslim and you love America and freedom and you hate terror, stay here and help us win and make a future together.”)

I haven’t reviewed the transcript of every convention speech. But I strongly doubt that the Clinton campaign asked any Mexican American, Jewish American, Asian American, Irish American, or Italian American speakers to declare their love for America and to disavow their connection a foreign power. Imagine, for instance, the furor that would have ensued had the Clinton campaign asked Debbie Wasserman Schultz to declare her “undivided loyalty to our country.”

I’m not naïve. Obviously, Khan included those words because his faith is now the object of public suspicion, just as John F. Kennedy’s was when he declared in 1960 that he believed in an America “where no public official either requests or accepts instructions on public policy from the Pope.” What’s depressing is that such a declaration is more politically necessary today than in 2004, 2008, or 2012—because in the years since 9/11, Islamophobia has not subsided. It has increased.

What has happened in the days since Khan’s speech has been inspiring and disturbing too. Trump has attacked Khan, and been roundly repudiated for doing so. But most of the outrage, from both politicians and pundits, has centered on Trump’s criticism of a Gold Star family. That misses the point. There’s nothing inherently wrong with openly disagreeing with someone who has lost a child in battle. If a Gold Star father became a prominent crusader against gay marriage, those of us who support gay marriage would have every right to publicly challenge him, the magnitude of his personal loss notwithstanding.

What made Trump’s attack odious was not that he criticized a father and mother who have lost a son in war. It’s that by suggesting that Ghazala Khan was not “allowed” to speak, he recapitulated the anti-Muslim bigotry that made her convention appearance necessary in the first place. The reason politicians and pundits should embrace the Khans and repudiate Trump is not because they are Gold Star parents and he is not. It’s because they are defending religious liberty while he is menacing it.

Celebrating Khizr Khan as a Gold Star father is easy because it’s apolitical. Every American politician and pundit, no matter their ideological bent, pays homage to military families. Celebrating Khizr Khan as a champion of Muslim rights, by contrast, is harder. After all, some of the same conservatives who salute the Khans for their wartime sacrifice simultaneously demand a ban on Muslim refugees and warn about the imposition of Sharia law in the United States.

Hopefully, this is merely a passing phase in American history. Seventy-five years ago, Japanese and African Americans also needed to go to war to “prove” that they deserved full citizenship. Khizr Khan is an inspiration. But I look forward to the day when an American Muslim father whose son protested the war in Iraq, rather than dying it, can also ascend a convention stage and demand the equal rights that he and his family deserve.

Corgis shall follow me all the days of my life

Remembering Tasha Tudor’s illustrated ‘The Lord Is My Shepherd’

At some point in the last few years, my mother solemnly handed my childhood mementos over to me in a large archival box. Inside it I found, among my little drawings and ceramic hearts, a book version of the 23rd Psalm called The Lord is My Shepherd, illustrated by Tasha Tudor. I was expecting a child myself and scrambling to assemble edifying books to read to her. While I’m not particularly religious and couldn’t in any case picture intoning the 23rd Psalm to an infant, I remembered the book as an old friend from my childhood shelf, keeping company with a small number of Christian-themed books for children, like Tomie DePaola’s Parables of Jesus, and later, The Chronicles of Narnia. I wouldn’t baptize my daughter, and it was unlikely that I would take her to church, but I liked the idea of having a few tasteful religious texts around the place.

I was baptized and confirmed; I was taken to church and sent to choir. I have lost the habit of religion, though I am occasionally surprised by the residue it leaves on my life. I admire faithful people, believing still that religious practice is some mark of virtue. I experience the customary reverent shivers in cathedrals and mosques and other holy places, if they are beautiful. I pray when it is expeditious, in a manner that has more to do with fear and a compulsive streak than with God — secret mantras and gestures learned not from the Episcopal Church, but devised in the childhood dark or on scary airplanes.

I had the baby and forgot about the book for a while, dutifully holding board books with black and white pictures in front of her blurred eyes as I had been instructed by the child development treatises. By God, this five-day-old is going to get her proper start in life, I thought, until I realized she was a sleeping peanut and I could watch television for most of the day. Now the baby is eighteen months old and opinionated. She’s obsessed with books that have flaps and wheels and things that pop out, and she likes to abandon stories mid-way through to pick up another book we’ve read thirty times that week. But sometimes she takes a book from the shelf and pads over to me and smacks my knee to pull her onto my lap and we arrange the book and her sippy cup just so, and she leans back and nestles her head under my chin and drinks her milk and sits through the whole story.

A few weeks ago, she padded over to me holding The Lord is My Shepherd. The book has that satisfying slightly loose spine of a book 30 years old or more, and firm, flexible, almost unctuous-feeling pages. “The Lord is my shepherd,” I read, feeling unaccountably embarrassed and weird, as though my child would judge me for reading to her about God. “Daggy,” she said, because the first illustration is a little girl watched over by a little corgi dog. “I shall not want,” I read. “Daggy,” the baby said: the little girl eats breakfast; a mother corgi gloats over her litter.

The 23rd Psalm as illustrated by Tasha Tudor is absolutely teeming with corgis. Corgis in green pastures; corgis beside the still waters; corgis in the shadow of death (represented by country graveyard and a circling hawk). The baby was delighted; but I had begun tearing up at verse 2, “He maketh me to lie down in green pastures” (corgis in a meadow, with cow). I was bawling by “Thou anointest my head with oil,” which shows the girl and the corgi sweetly embracing. “Daggy,” the baby said cheerily, while I blew my nose on my sleeve. At the last verse, “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever,” the girl and her corgi sit on a hill at twilight, looking up at the stars.

The second time we read the book, a few weeks later, I wept again.

One summer weekday I wandered into the church I used to attend and sat down in a pew, where I promptly burst into tears; obviously, encounters with forgotten but familiar Christian places and rituals cause an upswell of subterranean sentiment in me. But there is something particularly affecting about Tasha Tudor’s imagining of the old psalm. The little girl lives in a bucolic setting with beehives and fresh bread and small packs of happy-looking livestock. She romps barefoot through the forest with no fear, delighting in streams and sunbeams. A corgi is her “mostly companion,” as her city-dwelling counterpart Eloise might say. The world is good and clean and sweet-smelling and self-sustaining. Even the evil is naturalistic and part of the order of things: a hawk with its eye on a field mouse. There is no climate change, no civil war, no refugee crisis, no electoral politics. The lord is with her indeed.

This was evidently the defining feature of Tudor’s work; her 2008 New York Times obituary describes a delightfully eccentric person who believed she was a reincarnated ship captain’s wife from the nineteenth century. Tudor, whose given name was Starling Burgess, raised her four children on a homestead where she went barefoot and made clothing from home-grown flax, accompanied by up to 14 corgis at a time. (She could “play the dulcimer and handle a gun” and “find a four-leaf clover within five minutes.”) The illustrations from the book are so powerful, maybe, because they were animated by her personal vision of the good life, a life she evidently tried very hard to live.

But Tudor also finds the opioid root of the psalm itself, which encapsulates all the comforts of religion without any of its complications, its challenges to serve. The 23rd Psalm is about sheep and a shepherd, if you parse the metaphor, and sheep have it pretty good, assuming their shepherd is nice and their pastures are green. They just have to be themselves and go where they’re led. The optimism of the psalm seems both necessary and cruel now, when the year, the decade, has been marked with human suffering, drowned children, things that should be our responsibility to fix. “Everything is going to be okay,” the psalm says; never is the impossibility — the hubris — of that promise more obvious than when you become a parent. But I was a child when I was religious and thus my religion is that of a child’s. So I let the book tell my uncomprehending baby that everything will be okay, and I try to believe it myself.

Lydia Kiesling is the editor of The Millions. Read more of her writing here.

Corgis shall follow me all the days of my life was originally published in The Hairpin on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Read the responses to this story on Medium.

Smear Campaign 2016 Political Poop Bags from MetroPaws

MetroPaws has brought their popular Smear Campaign waste bags back for the 2016 election! (Longtime readers may remember the 2012 edition.) Whether as a gift or a gag, Democrap or Repooplican, these bags are sure to make a statement! Available online from MetroPaws.

Share This: Twitter | Facebook | Don't forget that you can follow Dog Milk on Twitter and Facebook.

© 2016 Dog Milk | Posted by capree in Grooming + Hygiene | Permalink | No comments

Track of the Day: 'Toccata and Fugue in D Minor'

All this week, Elaine—who writes our Politics & Policy Daily newsletter—has been soliciting reader responses to the question, “What song should Donald Trump come out to when he walks on stage Thursday night at the Republican National Convention?” Scores of you have written in, and Elaine will be announcing the top picks tomorrow, but right now, before The Donald struts out (or maybe flies out?) to the podium tonight, here’s an over-the-top entry from Susie that I couldn’t resist posting as a note, namely to publish the words “carnelian-red dripping maw”:

Trump’s walk-out melody at the RNC should be “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor.” Costume and staging matter, too. His entrance will be preceded by a veritable battalion of marching, naked-but-draped, blonde bombshells (literally). His profligately gilt-edged children—clearly branded TRUMP on their foreheads, and with all their strings and the master puppeteer visible by over-head projection—will also join the procession, dropping tiny-but-very-white redneck effigies along his walkway (to mark his path of retreat).

Trump enters with a dark and crookedly flowing cape sporting stripes pulsing in neon yellow. The papier mâché wall following him is decorated in pesos-stuffed piñatas and bordered in the blood of migrants. The music will abruptly stop on a loud and jarring note immediately upon him reaching the podium and just after the crowd-circulated collection plates have been gathered into his grasping hands. Photo op: His orange face will outshine his yellow pulsing stripes, and the green of Republican dollars falling from his blistered hands into the black hole of his drooling, carnelian-red dripping maw will sparkle in the light of a purple Lucifer’s welcoming embrace.

That’s not what Ben Carson had in mind. Or Boehner.

(Submit a song via hello@. Track of the Day archive here. Pre-Notes archive here.)

Perimenopause: a fun little play

(God and the Archangel Michael, ironing out some last details about humanity)

The Archangel Michael: Dear God, how do we inform women that it's time to stop procreating?

God: What do you mean, "time to stop"?

Michael: Well, they can’t do it when they’re 80, right? Their bones would break.

God: Oh, they’ll certainly be dead by 50. Look how many diseases I made up. (Points to diseases.)

Michael: But let’s say they figure out to wash their hands. Once they invent soap someone’s going to live longer than that, King of Kings.

God: "Soap?" Christ. Okay, so we end things. Let's say, 40, they're done. No, 55.

Michael: You said they’d be dead by…

God: Somewhere between 40 and 55. Leave it up to them.

Michael: Leave it up to… ?

God: Their bodies or whatever. Their bodies are temples, right? Didn’t I make that up?

Michael: And how will they become aware this is happening?

God: Cause their menses to cease, obviously. I COMMAND CESSATION!

Michael: It’s just us, All Knowing One. You don’t have to blow out my eardrums.

God: Sorry, sorry.

Michael: So it just … doesn’t come back? That seems rude.

God: You think they need a warning? You’re right, they need a warning.

Michael: I mean, it might be nice—

God: Hot flashes.

Michael: Excuse?

God: Yea, their bodies shall verily heat from within, as if an inner fire rages.

Michael: So they heat up, and then they know the childbearing years are over?

God: It happens just, like, from time to time, for a while.

Michael: What does a while mean?

God: Between 1 and 10 years! You know I hate details, Michael.

Michael: Got it. Some hot flashes for ... a while.

God: Also mood swings. We’re going to make them angry. And then freaked out. And then angry again. And hot!

Michael: You already said hot.

God: It's such an important part of the process. For some reason.

(Michael begins backing out of room)

God: Also! Their menses shall be royally fucked for a good long while. One cycle might be 15 days, the next one 96. Just really all over the fucking place. So that when it does go away, they’re nothing but pleased.

Michael: (stares at Him)

God: Isn’t that nice? Isn’t that a nice thing I’m doing? They’re not thinking about mortality when their bodies are going haywire.

Michael: I mean—

God: Wait! And pimples. They’re going to break out like they’re teenagers.

Angel: God, why—

God: That’ll teach them to live that long.

Michael: Okay, well. Good job, My Lord. I think we have a good long list now, so...

God: Oh, I’m just getting started.

Michael: (sighs, takes out notepad again)

God: Look, this is just for fun. We both know they’re never going to learn to wash their hands.

Poor at 20, Poor for Life

It’s not an exaggeration: It really is getting harder to move up in America. Those who make very little money in their first jobs will probably still be making very little decades later, and those who start off making middle-class wages have similarly limited paths. Only those who start out at the top are likely to continue making good money throughout their working lives.

That’s the conclusion of a new paper by Michael D. Carr and Emily E. Wiemers, two economists at the University of Massachusetts in Boston. In the paper, Carr and Wiemers used earnings data to measure how fluidly people move up and down the income ladder over the course of their careers. “It is increasingly the case that no matter what your educational background is, where you start has become increasingly important for where you end,” Carr told me. “The general amount of movement around the distribution has decreased by a statistically significant amount.”

Carr and Wiemers used data from the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation, which tracks individual workers’ earnings, to examine how earnings mobility changed between 1981 and 2008. They ranked people into deciles, meaning that one group fell below the 10th percentile of earnings, another between the 10th and 20th, and so on; then they measured someone’s chances of moving from one decile to another. But the researchers wanted to see not just the probability of moving to a different income bracket over the course of a career, but also how that probability has changed over time. So they measured a given worker’s chances of moving between deciles during two periods, one from 1981 to 1996 and another from 1993 to 2008.

They found quite a disparity. “The probability of ending where you start has gone up, and the probability of moving up from where you start has gone down,” Carr said. For instance, the chance that someone starting in the bottom 10 percent would move above the 40th percentile decreased by 16 percent. The chance that someone starting in the middle of the earnings distribution would reach one of the top two earnings deciles decreased by 20 percent. Yet people who started in the seventh decile are 12 percent more likely to end up in the fifth or sixth decile—a drop in earnings—than they used to be.

Overall, the probability of someone starting and ending their career in the same decile has gone up for every income rank. “For whatever reason, there was a path upward in the earnings distribution that has been blocked for some people, or is not as steep as it used to be,” Carr said.

Carr and Wiemers’ findings highlight a defining aspect of being middle class today, says Elisabeth Jacobs, the senior director for policy and academic programs at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, the left-leaning think tank that published Carr and Wiemers’ paper. “If you’re in the middle, you’re stuck in the middle, which means there’s less space for others to move into the middle,” she said. “That suggests there’s just a whole bunch of insecurity going on in terms of what it means to be a worker. You can’t educate your way up.”

This lack of mobility holds even for people with a college degree, the researchers found. Many college-educated workers started their careers at higher earnings deciles than those before them did, but also tended to end their careers in a lower decile than their predecessors. Women with college degrees also started off their careers earning at a higher decile than they used to, and the presence of more college-educated women in the workforce could be making it harder for men to move up the ranks.

Carr and Wiemers aren’t sure exactly why the American economy has become less conducive to economic mobility. The decline in unions may play a role: Organized labor was once better able to negotiate pay raises for their members, whatever their career stage. Carr and Wiemers also cite the work of the economist David Autor, who has found that the number of jobs at the bottom and the top of the pay scale is increasing, while the number of jobs in the middle isn’t. If there were more employment growth in the middle, those who start out at the bottom might have a better shot at moving up.

Increasing income inequality may play a role, too. Carr and Wiemers found that the earnings of the people in the top decile are much higher than they used to be, compared to the overall population. That means it is increasingly harder to reach those top ranks. “In the presence of increasing inequality,” they conclude, “falling mobility implies that as the rungs of the ladder have moved farther apart, moving between them has become more difficult.”

Thank Goodness for Sookie St. James

Her weight was never a topic of discussion on “Gilmore Girls.”

Everyone has that one favorite TV show that came along at the right time with the perfect storyline and characters to leave them totally devoted, defending it from detractors and rewatching until whole episodes are memorized. Some were all over “The West Wing” when it debuted. For me, it was Gilmore Girls.

It’s obvious that I’m not alone. Between the breaking-news-bulletins over the announcement that the series would be revived by Netflix and the popular podcast Gilmore Guys, it’s managed to remain relevant in pop culture even almost ten years after it went off the air. Some of the jokes haven’t aged well and references are laughable now for how dated they are (never forget that Howard Dean moment in season four). Even so, for me, the show is like a warm bowl of homemade soup, comfortable and familiar. I’ve watched an episode or two after scary movies to make myself feel better. Sure, no one in real life talks in quips and casual pop culture references — at least no one who isn’t trying to talk like a fictional character — but that just makes me love my escape to Stars Hollow even more.

I was the same age as Rory when the series started and now that I’m nearly the same age as Lorelai, I see the show from a new perspective. Still, my favorite character has remained the same: the funny, sunny, talented Sookie St. James, played by Melissa McCarthy (Kelly Bishop as the matriarch Emily Gilmore is a close second). Her character was the rare positive appearance of a fat person on television. Almost all other characters, especially at the time, were in the Fat Monica vein: cheap jokes and stereotypes. I’m convinced after living through the early aughts as a fat teenager, the age of low-rise jeans and bellybutton rings, that I can survive anything. My personality is more in line with the showy, outgoing Lorelai than the quiet, serious Rory, and I was still years away from any sort of self-acceptance. Seeing a character on screen who looked like the grown up version of myself, living her life without any hangups about her appearance was not a small thing, even if I wasn’t fully aware of it at the time.

Credit must go to the show creator Amy Sherman-Palladino for no subplots about Sookie trying to lose weight or side comments from Sookie wishing she could change her body. Her weight was never a topic of discussion at all. An early characteristic of Sookie was exaggerated clumsiness. In the pilot, before we ever see Melissa McCarthy on screen, we hear her. To be accurate, it wasn’t quite her so much as a clatter of pots and pans from a commotion she caused in the kitchen. Sookie cheerfully moves on, a clumsy-person cliché. Thankfully, this klutziness didn’t stick. Instead, the running jokes became more about Sookie’s obsessive attention to detail and the pride she takes in her work. When Lorelai and Sookie have their first major fight over possibly going into business together, Sookie holds her own and makes the flighty, emotional Lorelai promise that she’ll stick with their plan. Throughout the series, it wasn’t Lorelai with the stable family life, but Sookie, and it depended on her income.

The best lesson I learned from Sookie was about love. There’s a moment halfway through the first season where Lorelai, in a moment of annoyance, says to Sookie, “When did you become a relationship expert? You haven’t been in a relationship in years.” Lorelai immediately apologizes and Sookie forgives her, but it was obviously a painful remark. It also inspires her to do something about it. Later in the episode, Sookie asks her produce man, Jackson, if he’d like to go to dinner with her and he accepts. Rejection was far and away my number one fear as a teenager. Teased by my classmates, I felt constantly rejected and unwanted, but that’s not the same thing as actual rejection. The thought of being brave in this way terrified me. It wasn’t until years later, as I got closer to Sookie’s age, that taking the initiative lost its terror and became empowering. It feels good to take control of your destiny.

Watching Sookie’s relationship with Jackson flourish was like the universe telling me, “Relationships are possible! Just hang in there, kid!” My favorite episode of the whole series is the season two finale, “I Can’t Get Started.” It has everything: the Rory and Jess kiss (!), Lorelai and Christopher’s reunion then heartbreak, and the great wannabe-catchphrase “Oy with the poodles already.”

The best part for me, though, was the scene in the kitchen. Lorelai walks in on Sookie in her wedding dress redecorating her own cake in a fit of night-before-nervousness. A bad dream had her trying on her dress and veil before zooming down to make adjustments to her wedding cake. The two friends have a touching moment as Lorelai calms her down. Before leaving the kitchen, Lorelai says, “Hey Sookie.” “Yeah?” her friend responds. “You’re in your wedding dress.” Sookie looks down at herself almost as if just realizing she was wearing it. “I am.” “You’re beautiful,” Lorelai says, while Sookie beams. It’s such a funny, sweet, real moment that never makes the joke about Sookie getting married, the kind of scene that even in a state of teenage anxiety could make me think I might possibly meet my own Jackson someday. That imperfect, chubby me might get married someday and it wouldn’t be a punchline.

It’s been more than fifteen years since “Gilmore Girls” debuted and there hasn’t been a character quite like Sookie, even if her role lessened toward the end of the series. The British program “My Mad Fat Diary” is great, and definitely a big step forward, but what made Sookie special was that she was an adult, someone who wasn’t still going through a struggle of self-acceptance. I’m sure this whole thing has be strange for Melissa McCarthy herself, whose own weight yo-yo-ed during the series. She’s opened up in recent interviews about losing fifty pounds for the upcoming Ghostbusters movie while at the same time, Elle magazine chooses to use a close-up photograph for her cover. It has be weird for McCarthy to go back to the Stars Hollow set, but this fan is glad she’s doing it.

Andrea Laurion is a writer and comedian from Pittsburgh. She’s probably drinking coffee right now.

Thank Goodness for Sookie St. James was originally published in The Hairpin on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Read the responses to this story on Medium.

Mainlining Vitamins Is Silly and Harmful

You were up late drinking with clients. Your head is pounding, and all you want to do is to take an Advil and go back to bed. But you’re on a deadline. If you’re a believer in modern-day elixirs, it’s time to press the “whoops button” and get your day back with IV vitamins.

Celebrities have been touting them for years, citing vague life affirming and energy-boosting effects. “We got nuffffin but love & vittys in our veinzzzz #vitaminpush,” reads Miley Cyrus’s Instagram caption for a photo of the cringing singer with tubes taped to her tattooed arm. Now registered nurses from boutique clinics will show up at your office, home, or hotel room and hook you up to an IV bag full of fluids and nutrients for around $500. In a number of cities, IV vitamin clinic buses trawl the streets for clients.

The trouble is, there’s no evidence it works.

With names like The Hangover Club, VitaSquad, and The Drip Room, dozens of IV vitamin providers fall into the high-end alternative medicine sector, with no support from peer-reviewed studies. They all use Lactated Ringer’s Injection, a solution for fluid and electrolyte recovery, and various cocktails containing trace elements and an alphabet of vitamins.

Some even include the local anesthetic lidocaine, which can provoke life-threatening reactions, as well as the anti-oxidant glutathione, which has not been approved by the FDA as an IV product. Treatments last anywhere between 30 minutes and two hours depending on the volume of the cocktail and the size of your veins.

The moment a nutrient like magnesium or Vitamin C is formulated for injection, it becomes a prescription drug, because of all the ways it could go wrong. Done incorrectly the IV can cause a severe bloodstream infection, and any undissolved crystals can clog up capillaries in the lungs.

If these were the only drawbacks to vitamin IVs, it might be worth letting individuals make their own decisions about whether to use them. But these treatments have another cost. Some people with damaged intestines and preterm babies—whose digestive systems are not yet developed—receive all of their nutrition from intravenous drips.

"It's not a free ride. We see lots of infections, but people have been kept alive for decades that way," says Dr. David Seres, director of medical nutrition at Columbia University Medical Center’s Institute of Human Nutrition.

Unfortunately the United States suffers from a shortage of the very IV drugs and nutrients sold in vitamin therapy clinics. Since 2011, 90% of American hospitals have reported shortages in these products, and nutrients like calcium, fat, and vitamins have often been omitted from nutrition products for intravenously fed patients.

In that time, there has not been a single period when every nutritional component was readily available at once. In 2014, the FDA even temporarily allowed the import of saline from Europe to alleviate the constricted supply.

Unless you have some sort of intestinal problem that prevents you from absorbing nutrients, all of this water and all of these vitamins are just as easily taken up as part of your diet. And even then, the balance of evidence suggests taking vitamin supplements is a bad idea.

“I don’t think there’s a single vitamin that doesn’t have some toxicity associated with too much,” says Seres. “Just because something is a nutrient—a vitamin or an antioxidant—doesn’t mean that more is better.”

Indeed, randomized controlled studies show the wrong kind of correlation between vitamin supplements and some diseases, such as Beta-Carotene and lung cancer, calcium and heart disease, or vitamin E and prostate cancer. The “goldilocks rule” applies to most aspects of nutrition, and the recommended doses are a happy medium for healthy people.

It may come as a disappointment to fans of radical intervention, but the best cure for hangovers is temperance and the best source of vitamins is food.

When It’s Not a Game For You

Pokémon GO has exploded all over my life. My friends are playing it at work, others are boasting finds in my Facebook feed– this morning I watched a young family catch something outside my gate on their way to the farmer’s market. But I can’t stop thinking about this essay I read: Pokémon GO is a Death Sentence if you are a Black Man..

I have never been as aware of my white-based public safety as the time we were playing an Amazing Race-style game that required us to stop strangers in downtown Los Angeles and ask them if they had something for us. At one point we were even running toward Union Station, one of us yelling, “We have to do it now, we’re running out of time!”

My brain kept whispering, “Nobody is even batting an eye, while you’re running past people who would be detained, if not flat-out shot for doing what you’re doing.”

My friend was sure she’d found one of the “informants” who had our next clue. She called me over and told me she’d asked him if he had something, and he said that depended on if she could tell him what train you take to Hollywood. “This is how we get our next clue! Tell him, tell him!” The only problem was he was now being questioned by two bike cops who assumed he was harassing us.

This is where I mention he was black.

“I’m just going to give him directions,” I said.

“Ma’am, you don’t have to do that,” the officers said as they talked in code over the receivers near their shoulders.

“I want to,” I said. I was pretty sure he was the informant, but my friend was getting nervous, and it was getting tense around us. What am I supposed to say to the officers— “We’re okay here?” I didn’t summon them, they were already bothering him when I walked up, and I was frustrated that they thought they were interrupting either a drug deal or a panhandler — both of which were entirely race-based assumptions.

As officers again told us we should just walk away, I instead told the informant how to get to Hollywood. He opened up a folder from his messenger bag, and handed me my next clue.

He then turned to the bike cops. “It’s a GAME,” he said. After the officers left, I was feeling so shitty.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “All of that sucked.”

“You guys are the only ones with the clue, by the way,” he said. “None of these other people have even once come up to me.”

I would never play Pokémon GO — especially at night — because it sounds like the perfect way to get hit by a car, followed, or mugged. The things I have to think about when I walk alone out there are for who/what I am and what has happened to me. But it’s an entirely different thing to realize you can’t play a kid game because it makes you behave in a way that gets racists and profilers feeling antsy. Or maybe it isn’t different at all. Whatever it is, it’s definitely not a game.

Anxiety: even less fun than you'd think

[Psst: Before we begin this little play, I wanted to tell you that I now have a weekly newsletter! Sign up here. That is all.]

Looking over list of tasks for the day, Alice hears a disembodied voice*.

?: Ha ha, you’re not going to accomplish any of it. Again.

Me: Who said that?

?: Good morning. I am The Nameless, Formless Dread!

Me: I need to cut down on my coffee.

While working

Me: Huh. Did I eat something weird?

NFD: Hello. I am the Nameless, Formless Dread.

Me: Jesus—get off me! I’m trying to work.

NFD: I will help. That thing you’re doing is bad.

Me: How is this a help?

NFD: How about this? That thing you’re doing is very bad.

Me: Please unhook yourself from my abdomen.

NFD: But it’s so soft here. (whispers) Too soft.

After walking past group of neighbors who don’t seem to notice when Alice smiles hello

NFD: Nameless, Formless Dread, here! Ouch. That was awkward. Boy do they not like you.

Me: That’s ridiculous. Why would they dislike me?

NFD: (Shrugs) They have very good reasons that they’ve all agreed on but you’ll never know what those are.

When the phone rings

NFD: AAAAAAAAAAAAAGH DON’T ANSWER IT HIDE HIDE THE NAMELESS FORMLESS DREAD SAYS HIDE

Me: What the hell?

NFD: Someone is dead! Or mad at you!

Me (looking at number): It’s a telemarketer.

NFD: Why don’t your friends call? Oh, because you’re… never mind.

And then later

Me: (closing laptop)

NFD: Hey there, Nameless/Formless Dread, blah blah, hello, are you getting up? Where are you going?

Me: I have a thing I’m supposed to go to.

NFD: No way. Do you know how many things could happen to you out there? And why are you wearing that? Look, I brought kettle corn!

Me: This kettle corn is stale.

NFD: That's an early warning sign of dementia, you know. Thinking, uh, things are stale. I haven't thought this through yet. But don't worry, I will.

In bed

NFD (clambering atop my head): Oh no, oh no! You forgot! YOU FORGOT!

Me: What? WHAT?

NFD: … I can’t remember. Huh. Well, at least now you have all night to figure it out.

*(Don't worry, not really.)

The Problem With The World

“The problem with the world is that the intelligent people are full of doubts, while the stupid ones are full of confidence.”

– Charles Bukowski

Irish Fans are Winning Euro 2016

Say what you will about the Irish, but their fans are some of the most entertaining drunks on the planet. 6 examples below:

1. Irish fans sing lullabies to a French baby on a Bordeaux train.

2. Hundreds of Irish fans serenade French lifeguard Carla Roméra. She awards one of them with a kiss.

3. Irish fans in Paris sing to an older gentleman watching the crowd from his balcony.

4. Irish fans dent the roof of a French car, give the owner money for repairs, then work together to fix the dent themselves.

5. Irish fans chant “Go home to your sexy wives!” to Swedish fans prior to the Ireland/Sweden tie.

6. Other Irish and Swedish fans combine forces to sing Abba’s “Dancing Queen.”

Ireland plays Italy today.

—

Trump: Obama Was Maybe Involved in the Orlando Shooting

In an almost entirely unprecedented moment, Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee for president, suggested in interviews Monday morning that President Obama may have somehow been involved in Sunday’s massacre in Orlando.

Trump’s suggestion came by implication, but the message unmistakable: The president may have somehow known about or been involved in the shooting.

“He doesn’t get it or he gets it better than anybody understands—it’s one or the other and either one is unacceptable,” Trump said on Fox News. He had already called in a statement Sunday for Obama to resign from office. Trump added on Monday:

Look, we’re led by a man that either is not tough, not smart, or he’s got something else in mind. And the something else in mind—you know, people can’t believe it. People cannot, they cannot believe that President Obama is acting the way he acts and can’t even mention the words “radical Islamic terrorism.” There’s something going on. It’s inconceivable. There’s something going on.

During an interview on NBC’s Today show, Trump offered a slightly softer version of the accusation, suggesting Obama was willfully blind: “There are a lot of people that think maybe he doesn’t want to get it.”

The idea the president is a Manchurian candidate, a mole or agent for jihadism is a stunning accusation, even by the standard of a presidential campaign in which Trump has delivered a series of breathtaking statements, from comparing a rival to a child molester to being unable and unwilling to differentiate one of his policy ideas from Nazi policies.

Such conspiratorial beliefs are not unheard of in American politics, but they are typically banished to the margins. For example, some “Truthers” argued that President George W. Bush was either involved in or turned a blind eye to the 9/11 attacks. There’s no substantiation for those claims, and the people who hold them are generally viewed with derision. So, too, are those who have claimed that mass-shooting events such as the Sandy Hook massacre are “false flag” attacks, designed to drum up support for gun-control measures. The fringe radio host Alex Jones has already labeled Orlando a false flag, offering a sense of who Trump’s allies are on this issue.

What is unprecedented here is that the claims are coming from a major party’s presumptive nominee for president, but unhinged beliefs about Obama are not especially new, nor are they nearly so fringe. The conservative writer Andrew McCarthy argued in a 2010 book that Obama was part of a conspiracy with radical Islamists to subvert the U.S. government. More banally, many people have claimed that Obama is a Manchurian candidate (or a Manchurian president, perhaps), a non-U.S. citizen who is ineligible for the presidency. That claim, too, is bogus, contradicted by a raft of evidence, including Obama’s birth certificate and contemporaneous birth announcements in Hawaii newspapers. Nonetheless, polls as recently as this year have found a majority of Republicans questioning Obama’s citizenship.

These “Birthers” have been encouraged by supporters in upper echelons of politics. In 2011, for example, a prominent businessman began voicing doubts about Obama’s citizenship. He even said he had bankrolled investigators, sending them to Hawaii to look into the matter. (Whether he really did is unclear.) He even claimed that they’d turned up incriminating information. In the end, of course, no such evidence turned up, although the pressure did apparently convince Obama to release his “long-form” birth certificate, a white whale for birthers. Despite what might have been a discrediting experience for the businessman in the eyes of the public, he didn’t slink away and stay quiet. Instead, he ran for president in 2016, and he’s now the GOP nominee: Donald Trump.

He doesn’t even have testicles.

The Women Behind the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

In 1939, the National Academy of Sciences awarded a grant to the Suicide Squad, a group of three students experimenting with rockets at Caltech, now more formally known as the GALCIT (Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology) Rocket Research Project.

It came just in time.

Until then, the group, comprised of Frank Malina, Jack Parsons, and Ed Forman, had no way to fund the rockets they were working on, and was on the verge of disbanding. That first award, $1,000, rescued the group, bringing them back together. When they were awarded a second grant the next year for ten times as much, it was life-changing. It was the U.S. government’s first investment in rocket research. In deference to the Army Air Corps, which had proposed the funding, they changed their name to the Air Corps Jet Propulsion Research Project. Their goal was clear: Develop a rocket plane. The risky project was the beginning of what would become the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Knowing they would need skilled mathematicians, Frank approached his two friends, Barbara (Barby) and Richard Canright. Barby knew the job would be far from a sure thing. She wondered if she could depend on the longevity of the reckless group. She and Richard would be leaving good jobs to work for men who were not known for their reliability. Yet the offer was tempting.

If she accepted, Barby would once again be the only woman in a group of men. It was a job she hadn’t expected, yet one she was eminently qualified for. Math was a comfortable second skin. She would always feel more at home with a pencil in her hand than at a typewriter. In addition, the position held prestige, allowed her to work alongside her husband, and paid twice what she made as a typist. More than the money, it offered her the opportunity to use her neglected math skills.

It wasn’t just the rocket research group that Barby was becoming a member of. She was joining an exclusive group whose contributions spanned centuries. Before Apple, before IBM, and before our modern definition of a central processing unit partnered with memory, the word computer referred simply to a person who computes. Using only paper, a pencil, and their minds, these computers tackled complex mathematical equations.

Early astronomers needed computers in the 1700s to predict the return of Halley’s Comet. During World War I, groups of men and women worked as “ballistic computers,” calculating the range of rifles, machine guns, and mortars on the battlefield. During the Depression era, 450 people worked for the U.S. government as computers, 76 of them women. These computers, meagerly paid as part of the Works Progress Administration, created something special. They filled twenty-eight volumes with rows and rows of numbers, eventually published by the Columbia University Press as the plainly named Mathematical Tables Project series. What they couldn’t know was that these books, filled to the brim with logarithms, exponential functions, and trigonometry, would one day be critical to our first steps into space.

The dream of space exploration was what initially tugged at the Suicide Squad. They worked on engines during the day, but at night they talked about the limits of the universe.

At the time, rockets were considered fringe science, and the people who worked on them weren’t taken seriously. When Frank asked one of his professors at Caltech, Fritz Zwicky, for his help on a problem, the teacher told him, “You’re a bloody fool. You’re trying to do something impossible. Rockets can’t work in space.” In fact, the word rocket was in such bad repute that the group purposely omitted it when they formed their institute, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Some scientists at the sister Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology snickered at them, while Vannevar Bush, an engineering professor at MIT, derisively said, “I don’t understand how a serious scientist or engineer can play around with rockets.”

* * *

The Canrights were enjoying a quiet Sunday afternoon on December 7, 1941. Barby was in the kitchen, cooking and listening to the radio, when the announcer interrupted the program with breaking news. The Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. Barby fell to the kitchen floor, tears streaming down her cheeks. The war had hit home. Hawaii suddenly seemed very close to California. Barby and Richard were glued to the radio for the rest of the evening. Barby knew that their work would now take on a new importance. Going in to the lab the next day, they might have been talking about Pearl Harbor, but they were thinking about the rocket plane. The army needed to lift a fourteen-thousand-pound bomber into the air.

In one month, Barby filled more than twenty notebooks with rows of neatly printed numbers. Each column represented a value from the experiment, plugged into lines of exquisitely complex equations. One of the key computations Barby was responsible for was the thrust-to-weight ratio, an equation that allowed the group to compare the performance of the engines under different conditions. She repeated the calculation many times, sliding the numbers into the equation with the ease of slipping on a pair of shoes.

It was all building to one singular achievement.

It took just a year for the JPL rockets to boost the Douglas A-20A bomber into the air. They experimentally fired the JATO units on the heavy bomber forty-four times, the rockets needing only minor fixes. The project was a success.

All JPL needed now was more employees. Barby was excited when Frank told her he was hiring two more computers, a man and a woman, Freeman Kincaid and Melba Nead. Until then, Barby and Frank’s secretary had been the only two women at the institute. Barby, who didn’t spend much time with the secretary, had felt the lack of female companionship.

Barby’s husband was promoted to engineer. It was what Richard had always hoped for. Although Barby’s experience was similar to his, she was not promoted and hadn’t expected to be. It was simply one of the limits of being female. Although she loved her work, with Richard’s promotion and subsequent added income, she was thinking about starting a family.

Not long after Richard’s promotion, JPL hired two more women, Virginia Prettyman and Macie Roberts, rounding out the computer room to a team of five: four women and one man. The new recruits didn’t seem promising at first. Virginia and Macie, or Ginny and Bobby, as they soon became known, had never heard of a computer before. They answered the want ad with little idea of what they were getting themselves into. Despite the newcomers’ naïveté, the computers immediately became good friends. They spent every day working together, sweating over their calculations, observing experiments in the test pits, and chatting with the engineers.

The computer room worked as seamlessly as a machine, notebooks passed from desk to desk as the five colleagues spent their days transforming raw numbers into meaningful data. Their prize possession was a single Friden calculator. It looked nothing like the modern, sleek devices we’re used to today that can perform hundreds of functions and sit in the palm of our hand. Instead, the calculator was the size of a bread box and heavy. When they first received the Friden, Barby was excited to be in command of a machine that so few people knew how to use. It was the latest technology and much faster than a slide rule, though it could only add, subtract, multiply, and divide. It was a dull gray and looked like a typewriter, but instead of letters, the keyboard held rows of repeating numbers, from 0 to 9.

Melba, Macie, Virginia, Freeman, and Barby were responsible for calculating the potential of rocket propellants. During a conversation one day, Barby noted, “I hear Jack has an idea for a new one. …You’re not going to believe what it’s made of—asphalt.”