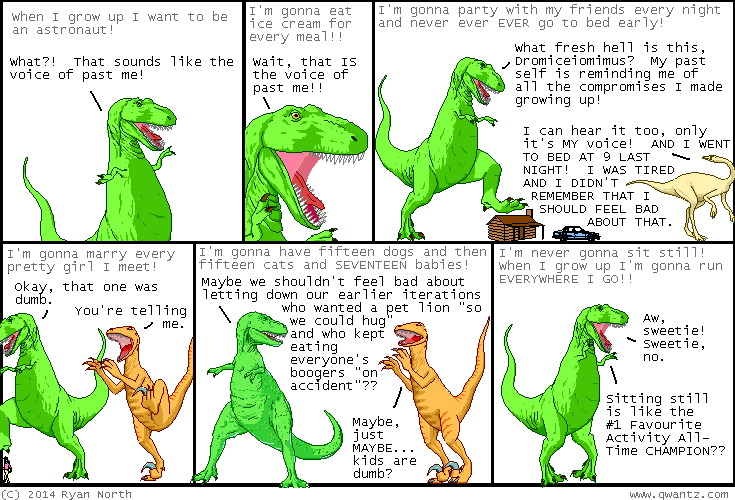

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | May 20th, 2014 | next | |

|

May 20th, 2014: Last night I dreamed that it was my job to describe how it feels to be a dog, but then I woke up into a world where it's my job to make dinosaurs talk in comics! I feel like I traded up!! – Ryan | |||

Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

i was so tired i forgot to feel bad about being so tired, OH WELL

#1032; In which a Dog is praised

UKIP, BBC, Vote Shares and Earthquakes

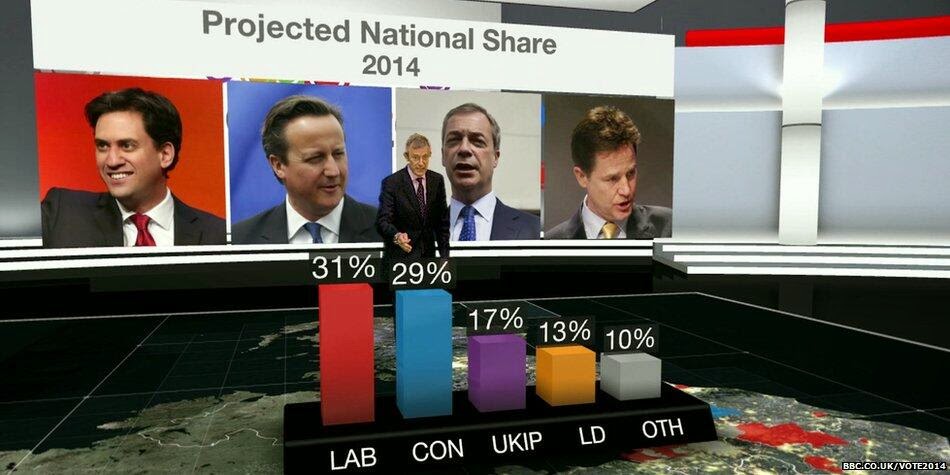

I think we can all be agreed that the #Vote2014 coverage of local council elections left a little to be desired. An over emphasis on the situation with UKIP, the audacity of sending reporters to clearly UKIP friendly areas and being flabbergasted at the fact that UKIP is something people talk about when asked about the elections, and generally spending their air time talking to politicians about what the public must be thinking based on the votes coming in rather than...you know...asking the public. At one point we genuinely had a two labour figures being interviewed against each other about the state of politics. Crazy.

However I'm sensing around social media that people are firmly still in the "denial" stage of grief when it comes to UKIP. You may argue with the term "earthquake", but it is utterly delusional to not agree that UKIP are facing a frantic surge in popularity every time an election rolls around. The reason why some are calling this an "earthquake" or a shake up of politics, or the beginning of four party politics, is that UKIP support is spreading (outside of London) and entrenching.

In 2012, the first real year of local "success" for UKIP they didn't have enough support to warrant giving them their own spot in the "projected national share" projections that the BBC creates from the councils it gets full results for. They polled 13% in the few places they stood, but this wasn't a wide enough base to give them any meaningful peg on the national vote share ladder.

Then came 2013, and a whopping 23% prediction of the national vote if this had been a general election.

However, yesterday comes and UKIP are "only" pegged at 17% in a projected national share, a full 4% above the Liberal Democrats and in third place. By any standards, in an election where such a large amount of the country's local councillors are elected, this is a big deal.

Cue "The Mass Denial". "Their support is dropping!" they say. "This doesn't matter because turnout is so low!" they say. "It's just a protest vote, it'll go away!" they say.

One of the sad things about politics, I find, is that generally people vote the same whether it's 20% of people voting or 70%. There are of course not insignificant variations as different interest groups and political groups are brought into the fold by higher turnout, and higher turnout has the general effect of moving the pointer from one direction (usually the disaffected protestors) to another (the prgamatic and loyal). You can see it from previous projected national shares of the vote, taking what people do on a turnout of 35% nationally can translate into a fairly decent idea of what would happen at 60-70% turnout.

Look at 2009. Lib Dems are a viable third place party by this point, however they were also seen as a party propped up by protest votes. The BBC gave them a projected national share of 28% compared to Labour's 23%, with the Tories on a downward trend at 38%. The actual 2010 result? Tories 36%, Labour 29% and Lib Dems on 23%.

Labour voters turned up at the General Election in a way they didn't at local elections, and by contrast Lib Dems fared worse on vote share nationally with their MPs than their councillors. Is this the key to showing that UKIP's support is a protest vote like Lib Dems? That their 17% will fall to 12% or below?

Perhaps, or perhaps because demographically the Lib Dems and UKIP are mirror images of each other, with UKIP commanding a legion of fringe supporters that are a) Motivated for wholesale change rather than just no tuition fees and b) part of a generation that holds a sense of civic pride in voting, the chances of their share dropping quite so high as that of the Lib Dems circa 2009-2010?

But what of this idea their support is dwindling? A fantasy, as far as I'm concerned.

In 2013, the first year where the BBC deemed it necessary to give UKIP their own slot on the projected national share, was a year where many councils were electing their councillors, but not London, not Wales, not a number of larger areas and cities. Previously UKIP had been part of "Others" which had a share of 15%, but were left with 9% when UKIP moved out.

Going from around 5-6% as part of the "Others" to 23% was always a monumental leap. It was likely questioned at the time by the very people now using it as gospel to show that UKIP are "on the slide" rather than on a surge.

But it didn't include areas that we now know are not very UKIP friendly, predictably areas with higher proportions of migrants and diverse communities. If you take the results from places like London away this notion that UKIP have done worse than in 2013 slips away very easily. They have, more accurately, performed about the same as last year if not a little better.

Their council seat wins are consistent with 2013, and in seats that they didn't win they've started to put themselves in 3rd or even 2nd spots. They've not won any councils, but quite frankly it would be a thunderous earthquake if, in the space of two years, UKIP gained control of a council let alone more than one.

Then there is national polling.

Opinion polls are fairly reliable. People that aren't seeing the results they want like to believe they're not, and people that are seeing results they want maybe put a little bit too much stock in individual ones. Take the Greens. They feel they're surging, despite their opinion levels being fairly consistent except into the run up of the EU elections for years (and in the EU polling they're doing no better than 5 years ago). But I digress.

In 2012 ICM (in my opinion the most accurate pollster) put UKIP around the local election dates on 3-4%. In 2013 at the same point of the year it was 18%, though this was a clear outlier where a support level of 7-9% is more accurate, and in 2014 is is keeping around 9-11%.

This is not the trend of a party losing support, it is one of a steady rise in support of nearly 10% in two years, though we should wait a few more months for these particular elections (and the outliers they seem to generate) to see how much more this could potentially rise. It's also worth noting that these spikes in support really seem to translate in to spikes in voting. In my opinion it's not all coincidence their support was around 18% in the lead up to the 2013 local elections and the 17% they're projected right now.

UKIP are here, and they may not realistically be much more of a party than the Greens are as it stands, but they are also showing all the signs of taking this seriously. The BNP were just a bunch of ranty, illiterate, racists that managed to somehow pool enough brainpower to form a party. UKIP are already talking, quite sensibly, about how they're going to target seats to grow their support, to grow their volunteer base...to do all the things a serious political party does to move from being a protest party into one that retains consistent base levels of support.

Best case scenario at the moment is that their support plateaus while the other parties work out a way to mitigate the effects of the UKIP narrative, but with Labour seemingly happy to play deferentially to UKIP as if they have the answers, and Tories not quite sure whether they should be attacking UKIP or trying to show people that they're not that different from them, I'm not sure that's a guaranteed outcome either.

Sitting and pretending the rise of UKIP isn't happening, or being anal over whether or not this constitutes an "earthquake" or not is a waste of effort. The question right now is if the large number of people not voting feel proportionally any different to the proportion of people that voted, and for the other parties to find the solution to getting those usually non-voting people into the voting booths...and to find that solution fast because UKIP seem to have got a solution all of their own and they're already using it.

The Blame Game

UKIP SURGE AHEAD ON SHABOGAN GRAFFITI

THE BBC NEWS DIVISION HAS TAKEN OVER OWNERSHIP OF OBSCURE DOCTOR WHO BLOG SHABOGAN GRAFFITI

"The blog will now be run according to proper BBC guidelines of impartiality," said that lying Zionist shitsack James Harding, head of BBC News.

In other news...

UKIP SURGE FORWARD AND ONWARDS TO CERTAIN FORWARD MARCHING MARCH OF ONWARD SURGING SURGENESS AHEAD ON SHABOGAN GRAFFITI.

The BBC Newsroom is reporting that despite there being no sentiments ever expressed on Shabogan Graffiti that a Ukipper would ever find acceptable, UKIP have broken through with a breakthrough on Shabogan Graffiti and are now surging forward and ahead to breakthroughs and surges on the unpopular blog.

"Apparently the vast majority of the British electorate do not read Shabogan Graffiti," said a hairdo on top of a suit behind a desk, "but even so, the fact that UKIP have now broken through and surged across the blog shows clearly that the British public think UKIP are a force to be reckoned with and a reckon to be forced with and surging and breaking through and getting the mainstream establishment parties running scared."

Finally...

BBC ANNOUNCES NEW SERIES OF POSTS ON SHABOGAN GRAFFITI, TO BE ENTITLED 'IMMIGRATION: ASKING THE DIFFICULT QUESTIONS THAT MOST WHITE WORKING CLASS PEOPLE WANT ANSWERED BUT WHICH THE POLITICAL CORRECTNESS NAZIS REFUSE ANY OF US TO TALK ABOUT'.

Andrew Marr is 412 years old.

SSC Gives A Graduation Speech

[Trigger warning for deliberately provoking horror about graduates' real-world post-college prospects]

[Epistemic status: intended as persuasive speech, may somewhat overstate case]

Ladies and gentlemen, I am honored to have been invited to speak here at the great University of [mumble]. Go Wildcats, Spartans, or Eagles, as the case may be!

I apologize if what I have to say to you sounds a little unpolished. I was called in on very short notice after your original choice for graduation speaker, Mr. Steven L. Carter, had his invitation to speak rescinded due to his offensive and quite honestly outrageous opinions. Let me say in no uncertain terms that I totally condemn him and everything he stands for, and that I am glad to see the University of [mumble] taking a strong stand against this sort of thing.

Ladies and gentlemen, probably the most famous graduation speech in history was Kurt Vonnegut’s “Wear Sunscreen” address. I’m sure you’ve all heard about it. He told an MIT class that they should wear sunscreen. Because for all he knew any more substantial advice he gave might be wrong, but that at least was on a firm evidential basis.

Well, I come here before you to explain that there is now serious controversy in the dermatological community. A 1995 paper found that people who used more sunscreen had a much higher risk of malignant melanoma, the most dangerous type of skin cancer. Eight years later, a review article claimed that the original paper was confounded by fairness of skin, and that likely the relationship between sunscreen use and melanoma is zero. But the story was further complicated by the finding that sunscreen use may increase cancers of the internal organs, either through vitamin D dependent or some vitamin D independent pathways. My understanding is that a majority of dermatologists are still in favor of sunscreen, but that the issue is by no means settled.

But think about what the disagreement means. One of the smartest men in America came before an auditorium just like this, and said that there was only one item of advice of which he was completely certain – that you should wear sunscreen. Absolutely certain. And years later, we know that not only is this a very complicated question on which no certainty is yet possible – but it may very well be that if you follow his advice, you will get cancer and die.

Sometimes the things everybody knows everybody knows just aren’t true. Like, did you know Vonnegut never wrote a graduation speech about sunscreen at all?

So with this spirit of questioning assumptions in mind, I want to ask you a question. Today many of you will be completing your education. Sure, some of you are going on to graduate or professional training, but it is clearly the end of an era. Seventeen years, from kindergarten to the present, and I want to ask you:

Is education worth it?

This sounds like the introduction to every college graduation speech ever. The speaker will ask if education is worth it, say of course it is because something something the human condition, and everyone will cheer and head off to the reception. So in order to keep you on your toes, I want to make the opposite point. What if education, as you understand it – public or private or charter schooling from age four or five all the way to university as young adults – is, on net, a waste of your time and money?

In order to move beyond platitudes in evaluate whether education is worthwhile – to give it the same kind of fair hearing we would want to give sunscreen – we need to list out some of the costs and benefits. Of benefits, two stand out clearly. The philosophical benefits of feeling connected to the beauty of mathematics, the passion of the humanities, the great historical traditions. And the practical benefits of being able to get a job and afford nice things like food and shelter.

We will start with philosophy. Human knowledge is pretty great. Your life has been enriched with the ideas of brilliant thinkers, of giants upon whose shoulders you might one day hope to stand. Isn’t this enough?

But as 86% of you know, you can’t just observe an experimental group has experienced an effect and attribute it to the experimental intervention. You have to see if other people in a control group got the same benefit for less work.

What would be the control group for school? Home-schoolers do much better than those who attend public or private schools by nearly any measure. But this is unfair; it’s what scientists call an “active control”. What we really need to do is compare you to people who got no instruction at all.

It’s illegal not to educate a child, so our control group will be hard to find. But perhaps the best bet will be the “unschooling” movement, a group of parents who think school is oppressive and damaging. They tell the government they’re home-schooling their children but actually just let them do whatever they want. They may teach their kid something if the child wants to be taught, otherwise they will leave them pretty much alone.

And this is really hard to study, because they’re a highly self-selected group and there aren’t very many of them. The only study I could find on the movement only had n = 12, and although it tried as hard as it could to compare them to schoolchildren matched for race and family income level and parent education and all that good stuff I’m sure there’s some weirdness that slipped through the cracks. Still, it’s all we’ve got.

So, do these children do worse than their peers at public school?

Yes, they do.

About college we still know very little. But if you’d stayed out of public school and stayed home and played games and maybe asked your parents some questions, then by the time your friends were graduating twelfth grade, you would have the equivalent of an eleventh-grade education.

Another intriguing clue here is Louis Benezet’s experiment with mathematics instruction. Benezet, an early 20th century superintendent of schools, wondered whether cramming mathematics into kids at an early age had a detrimental effect. He decreed that in some of the schools in his district, there would be no math instruction until grade six. He found that within a year, these sixth graders had caught up with their peers in traditional schools, and furthermore that they were able to think much more logically about math problems – figure out what was going on rather than desperately trying to multiply and divide all the numbers in the problem by one another. If Benezet’s results hold true – and on careful reading they are hard to doubt – any math education before grade six is useless at best. And it’s hard to resist the urge to generalize to other subjects and children even older still.

Why is it so easy for the unschooled to keep up with their better educated brethren? My guess is that it’s because very little learning goes on at school at all. The proponents of education speak of feeling connected to the beauty of mathematics, the passion of the humanities, and the great historical traditions. But how many of the children they spit out can prove one of Euclid’s theorems? How many have been exposed to the Canterbury Tales? How many have experienced the sublime beauty of the Parthenon?

These aren’t rhetorical questions, by the way. According to the general survey of knowledge among college students, 3.3% know who Euclid was, 7.6% know who wrote Canterbury, and a full 15% know what city the Parthenon’s in.

36% of high school students know that an atom is bigger than an electron, rather than vice versa. But a full 59% of college students know the same. That’s a whole nine percent better than chance. On one of the most basic facts about the fundamental entities that make up everything in existence.

“But knowledge isn’t about names and dates!” No, but names and dates are the parts that are easy to measure, and it’s a pretty good bet that if you don’t know what city the Parthenon’s in you probably haven’t absorbed the full genius of the Greek architectural tradition. Anyone who’s never heard of Chaucer probably doesn’t have strong opinions on the classics of Middle English literature.

So in contradiction to the claim that education is necessary to teach beautiful and elegant knowledge, I maintain first that nearly nobody in the educational system picks this up anyway, that people who don’t get any formal education at all pick it up nearly as much of it, and that people not exposed to it as children will, if they decide to learn it as adults, pick it up quickly and easily and without the heartbreak of trying to cram it into the underdeveloped head of a seven year old.

What about the claim that education is practically useful for getting a job and making money?

Even more than most young people, you’ve had the privilege of getting to watch your dreams implode in real time right before your eyes. About fifteen percent of you will be some variant of unemployed straight out of college. Another ten percent will find something part-time. And another forty or so percent will be underemployed, working as waiters or clerks or baristas or something else that uses zero percent of the knowledge you’ve worked so hard to accumulate. The remaining third of you who get something vaguely resembling the job you signed up for will still have to deal with wages that have stagnated over the last decade even as working hours increased and average student debt nearly doubled.

But don’t worry, I’m sure the nice folks at Chase-Bear-Goldman-Sallie-Manhattan-Stearns-Sachs-Mae-FEDGOV will be happy to forgive your debt if you mention you weren’t entirely happy with the purchase. You did hold out for the satisfaction-guaranteed offer, right? No? Uh oh.

As bad as the job market is, staying in school looks worse. Economists warn that attending law school is the worst career decision you can make, so much so that newly graduated lawyers have nothing do to but sue law schools for not warning them against attending and established firms offer an Anything But Law School Scholarship to raise awareness of the problem. Doctors are so uniformly unhappy that they are committing suicide in record numbers and nine out of ten would warn young people against going into medicine. Graduate school has always been an iffy bet, but now the ratio of Ph. D applicants to open tenure track positions has hit triple digits, with the vast majority ending up as miserable adjunct professors who juggle multiple part time jobs and end up making as much as a Starbucks barista but without the health insurance.

I’d like to thank whoever figured out how to include URLs in speeches, by the way. That was the best invention.

But here I cannot honestly disagree with the conventional assessment that going to school raises your earning power. As bad as you will have it, everyone who didn’t graduate college still has it much, much worse. All the economic indicators agree with the signs from the desolate wasteland that was once our industrial heartland: they are doomed. Their wages are not stagnating but actively declining, their unemployment rate is a positively Greek thirty-five percent, and prospects for changing that are few and far between. Some economists blame globalization, which makes it easy to outsource manufacturing and other manual labor to the Chinese. Others blame technology, noting that many of the old well-paying blue-collar jobs are done not by foreigners but by machines. Both trends are set to increase, turning even more factory workers, truck drivers, and warehouse-stockers into burger-flippers, Wal-Mart greeters, and hollow-eyed unemployed.

But don’t let your schadenfreude get the better of you. Twenty years from now that’s going to be you. Sure, right now machines can only do the easy stuff, and the world isn’t interconnected enough to let foreigners do anything really subtle for us. But lawyers are already feeling the pinch of software that auto-generates contracts, and programmers are already feeling the pinch of Indians who will work for half the pay and email their code to Silicon Valley the next morning. You don’t need to invent a robo-drafter to put engineers out of business, just drafting software so effective it allows one engineer to do the work of three. And although there are half-hearted efforts to stop it, it seems more and more like King Canute trying to turn back a tide made of hundred dollar bills.

Once machines can do everything we can better and cheaper, the inevitable end result is employment for a few geniuses who invent and run the machines, immense profits for the capitalists who own the machines, and what happens to everyone else better left unspoken.

“Is this a vision of what shall be, or of what might be only?” Well, a visionaries as diverse as Martin Luther King, Richard Nixon and Milton Friedman have proposed something called a Basic Income Guarantee. When society becomes so advanced that it produces more than enough for everybody – but also so advanced that most individuals below genius level have little to contribute and no way of earning money – everyone should get a yearly salary just for existing. Think welfare, except that it goes to everybody, there’s no stigma, and it’s more than enough to live on. This titanic promise has run up against a giant iceberg with BUT HOW WOULD WE PAY FOR IT written in big red letters on the front. If we cancelled all existing welfare and entitlement programs – which makes sense if we’re giving everyone enough money to live comfortably on, we would only free up enough money together for a universal income of $5,800. I don’t know if you can live on that, but I’d hate to have to try.

But we’ve gotten off track. We were counting the benefits of formal education. We did not do so well in trying to prove that it left you more knowledgeable, but it did seem like it had some practical value in getting you a little bit more money. With your shiny college degree, you can confidently assert “I’ve got mine”, just as long as you take care not to notice the increasingly distant hordes of manual laborers or the statistics showing that the yours you’ve got is less and less every year.

What of the costs of education? What have you lost out on?

Well, first about twenty thousand hours of your youth. That’s okay. You weren’t using that golden time of perfect health and halcyon memories when you had more true capacity for creativity and imagination and happiness than you ever will again anyway. If you hadn’t had your teachers to tell you that you needed to be making a collage showing your feelings about The Scarlet Letter, you probably would have wasted your childhood seeing a world in a grain of sand or Heaven in a wild flower or something dumb like that.

I’m more interested in the financial side of it. At $11,000 average per pupil spending per year times thirteen years plus various preschool and college subsidies, the government spends $155,000 on the kindergarten-through-college education of the average American.

Inspired by a tweet: what if the government had taken this figure (adjusted for inflation) and invested it in the stock market at the moment of your birth? Today when you graduate college, they remove it from the stock market, put it in a low-risk bond, put a certain percent of the interest from that bond into keeping up with inflation, and hand you the rest each year as a basic income guarantee. How much would you have?

And I calculate that the answer would be $15,000 a year, adjusted for interest. We can add the $5,800 basic income guarantee we could already afford onto that for about $20,000 a year, for everyone. Black, white, man, woman, employed, unemployed, abled, disabled, rich, poor. Welcome to the real world, it’s dangerous to go alone, take this. What, you thought we were going to throw you out to sink or swim in a world where if you die you die in real life? Come on, we’re not that cruel.

So when we ask whether your education is worth it, we have to compare what you got – an education that puts you one grade level above the uneducated and which has informed 3.3% of you who Euclid is – to what you could have gotten. 20,000 hours of your youth to play, study, learn to play the violin, whatever. And $20,000 a year, sweat-free.

$20,000 a year isn’t much. The average mid-career salary of an average college graduate is nearly triple that – $55,000. By the numbers your education looks pretty good. But numbers can be deceiving.

Consider the life you have to look forward to, making your $55,000. The exact profession that makes closest to that number is a paralegal, so let’s go with that. You get a job as a paralegal in a prestigious Manhattan law firm. You can’t afford to live in Manhattan, but you scrounge together enough money for a cramped apartment in Brooklyn, which costs you about $2000 a month rent. Every morning you wake up at 7:45, get on the forty-five minute subway ride to Manhattan, and make it to work by your 9:00 AM starting time. Your boss is a kind of nasty lawyer who is himself upset that he can’t pay back his law school debt and yells at you all day. By the time you get back home around 6, you’re too exhausted to do much besides watch some TV. You don’t really have time to meet guys – I’m assuming you’re a woman here, sixty percent of you are, I blame the patriarchy – so you put out a personal ad on Craigslist and after a while find someone you like. You get married after a year; your honeymoon is in Vermont because his company won’t give him enough time off to go any further.

You have two point four kids, and realize you’ve got to move to a better part of town because your school district sucks. Combined with your student debt, that puts a big strain on the finances and you don’t have enough to pay for child care. Eventually you find a place that will do it for cheap, and although it looks kind of dirty and you’re shocked when Junior calls you a “puta” which isn’t even a proper English curse word the price is right and they’re the only people who will accept four tenths of a kid. The older kids keep asking you and Dad for help with homework, which you can’t give because you haven’t really had time to keep up with your math and grammar and so on skills, what with the paralegal job and the television-watching taking up all your time. So you tell them to ask their teacher for extra help, which their teacher doesn’t give because she’s got forty other kids asking for the same thing and only twenty-four hours in a day. Despite all of this Junior gets into college and you sure haven’t saved up the money to put him through there tuition has spiraled to twelve gazillion dollars by this point and Chase-Bear-Goldman-Sallie-Manhattan-Stearns-Sachs-Mae-FEDGOV can’t lend him that because gazillion isn’t even a real number, and ohmigod what if Junior ends up one of those high school graduates with the Greek-level unemployment rates standing forlornly in front of a decaying factory in the Rust Belt? Worse, what if he ends up living with you? You beg him to go back to the bank and offer to pay whatever interest rates they ask. And so the cycle begins anew.

Or consider your life on a $20,000 a year income guarantee. No longer tied down to a job, you can live wherever you want. I love the mountains. Let’s live in a cabin in Colorado, way up in the Rockies. You can find stunningly beautiful ones for $500 a month – freed from the mad rush to get into scarce urban or suburban areas with good school districts, housing is actually really cheap. So there you are in the Rockies, maybe with a used car to take you to Denver when you want to see people or go to a show, but otherwise all on your own except for the deer and squirrels. You wake up at nine, cook yourself a healthy breakfast, then take a long jog out in the forest. By the time you come back, you’ve got a lot of interesting thoughts, and you talk about them with the dozens of online friends you cultivate close relationships with and whom you can take a road trip and visit any time you feel like. Eventually you’re talked out, and you curl up with a good book – this week you’re trying to make it through Aristotle on aesthetics. The topic interests you since you’re learning to paint – you’ve always wanted to be an artist, and with all the time in the world and stunning views to inspire you, you’re making good progress. Freed from the need to appeal to customers or critics, you are able to develop your own original style, and you take heart in the words of the old Kipling poem:

And none but the Master will praise them

And none but the Master will blame

And no one will work for money

And no one will work for fame

But each for the joy of the working

Each on his separate star

To draw the thing as he sees it

For the God of things as they are

One of the fans of your work is a cute girl – this time I’m assuming you’re a man, I’m sure over the past four years you’ve learned some choice words for people who do that. You date and get married. She comes to live with you – she’s also getting $20,000 a year from the government in place of an education, so now you’re up to $40,000, which is actually very close to the US median household income. You have two point four kids. With both of you at home full time, you see their first steps, hear their first words, get to see them as they begin to develop their own personalities. They start seeming a little lonely for other kids their own age, so with a sad good-bye to your mountain, you move to a bigger house in a little town on the shores of a lake in Montana. There’s no schooling for them, but you teach them to read, first out of children’s books, later out of something a little harder like Harry Potter, and then finally you turn them loose in your library. Your oldest devours your collection of Aristotle and tells you she wants to be a philosopher when she grows up. Evenings they go swimming, or play stickball with the other kids in town.

When they reach college age, your daughter is so thrilled at the opportunity to learn from her intellectual heroes that she goes to Chase-Bear-Goldman-Sallie-Manhattan-Stearns-Sachs-Mae-FEDGOV and asks for a loan. They’re happy to give her fifteen thousand, which is all college costs nowadays – only the people who are really interested in learning feel the need to go nowadays, and supply so outpaces demand that prices are driven down. She makes it into Yale (unsurprising given how much better home-schooled students do) studies philosophy, but finds she likes technology better. She decides to become an engineer, and becomes part of the base of wealthy professionals helping fund the income guarantee for everyone else. She marries a nice man after making sure he’s willing to stay home and take care of the children – she’s not crazy, she doesn’t want to send them to some kind of institution

Your younger son, on the other hand, is a little intellectually disabled and can’t read above a third-grade level. That’s not a big problem for you or for him. When he grows older, he moves to Hawaii where he spends most of his time swimming in the ocean and by all accounts enjoys himself very much.

You’re happy your son will be financially secure for the rest of his life, but on a broader scale, you’re happy that no one around you has to live in fear of getting fired, or is struggling to make ends meet, or is stuck in the Rust Belt with a useless skill set. Every so often, you call your daughter and thank her for helping design the robots that do most of the hard work.

Would you like to swing on a star? Carry moonbeams home in a jar? And be better off than you are? Or would you like to get a formal education?

We’re finally getting back to the point now. I’m sorry it’s taken this long. I can see the Dean of Students checking her watch over there with a worried look on her face. I think she’s worried I’m trying to filibuster your graduation. You know legally if I can keep speaking until midnight tonight, the graduation is cancelled and you have to stay in school another year? It’s true. Those are the rules.

Because I don’t want to talk about the very broad social question of whether Education the concept is worth it to Society as a concept. I want to ask you, standing here today, was your education worth it?

Because this is a college graduation speech, and I am legally mandated to offer some advice, and the specific advice I give will be tailored to your response.

Some of you will say yes, my education was worth it. I am the 3.3%! I know who Euclid was and I understand the sublime beauty of geometry. I don’t think I would have been exposed to it, or had the grit to keep studying it, if I hadn’t been here surrounded by equally curious peers, under the instruction of enthusiastic professors. This revelation was worth losing my cabin in Colorado, worth resigning myself to the daily grind and the constant lurking fear of failure. I claim it all.

And to you my advice is: if you’ve sacrificed everything for knowledge, don’t forget that. When you are a paralegal in Brooklyn, and you get home from work, and you are very tired, and you want to curl up in front of the TV and watch reality shows until you are numb, remind yourself that you value knowledge above everything else, that you will seek intellectual beauty though the world perish, and read a book or something. Or take a class at a community college. Anything other than declaring knowledge your supreme value but becoming a boob.

Others of you will say yes, my education was worth it. Not because of what I learned about ukulele or eucalyptus or whatever, but because of the friends I made here, the proud University of [mumble] spirit of camaraderie, which I will carry forth my entire life.

And to you my advice is similar: if you’ve sacrificed everything for friendship, don’t forget that. When you are a paralegal in Brooklyn, or a market analyst in Seattle, or God forbid an intern in Michigan, and you get home from work, and you are very tired, and you want to curl up in front of your computer and check Reddit, remind yourself of the friends you made here and give them a call. See how they’re doing. Write them a Christmas card, especially if it is December. Anything other than declaring friendship your supreme value and drifting out of touch.

Others of you will say yes, my education was worth it. Not because of what I learned about the Eucharist or eucre or whatever, but because of the connections I made, the network of alumni who will be giving me a leg up in whatever I choose to pursue.

And to you my advice is, again, similar. If you’ve sacrificed everything for ambition, be ambitious as hell. When you are a paralegal in Brooklyn or whatever, claw your way to the top, stay there, and use it to do something important. If you’ve sacrificed everything for ambition, don’t you dare stop at middle manager.

Others of you will say yes, my education was worth it. Not because of what I learned about yucca or the Yucatan or whatever, but because it helped me learn civic values, become a better person who is better able to help others.

And to you my advice is once again similar. If you’ve sacrificed everything to help others, don’t let it all end with donating a tenner to the OXFAM guy on the street now and then. Join Giving What We Can or go volunteer somewhere. If you’ve sacrificed everything for others, make sure others get something good out of the deal!

Others of you will say yes, my education was worth it. Not because of what I learned about eukaryotes or Ukraine or whatever, but because formal education in the school system taught me how to think.

And to…sorry, one second, HAHAHAHAHAHHAHAAAHAHAHAHHHAAHAHA HAHAHAHAHAHHA HAHAHAHAHAHAH HAHAHAHHHHHAAAHAHAHAHAH HAHAHHA HAHAHHHHAHAH HAAHHHAHA HAAHAHAHAHHA HAHHAHAHAHAHAHHAHA AHHHHAHAHAHAHA HAHAHAHAHA HHAAAHAHHAAHHAHA AHHAHAHAHAHA hahaha haha ha hahaha haha heh heh heh okay.

I’m sorry. Ahem. To you my advice is, again, similar. If you’ve sacrificed everything to learn how to think, learn how to think. When someone says something you disagree with, before you dismiss a straw man it and call that person names and slap yourself five for your brilliant rebuttal, take a second to consider it fairly on its own terms. Go learn about biases and heuristics and how to avoid them. Read enough psychology and cognitive science to figure out why your claim might kind of inspire hysterical laughter from people even a little familiar with the field. Just don’t sacrifice everything to learn how to think and end up only rearranging your prejudices.

And finally, some of you will say, wait a second, maybe my education wasn’t worth it. Or, maybe it was the best choice to make from within a bad paradigm, but I’m not content with that. And I wish someone had told me about all of this more than fifteen minutes before I graduate.

And to you I can offer a small amount of compensation. You have learned a very valuable lesson that you might not have been able to learn any other way.

You have learned that the system is Not Your Friend.

I use those last three words very consciously. People usually say “not your friend” as an understatement, a way of saying something is actively hostile. I don’t mean that.

The system is not your friend. The system is not your enemy. The system is a retarded giant throwing wads of $100 bills and books of rules in random directions while shouting “LOOK AT ME! I’M HELPING! I’M HELPING!” Sometimes by luck you catch a wad of cash, and you think the system loves you. Other times by misfortune you get hit in the gut with a rulebook, and you think the system hates you. But either one is giving the system too much credit.

Every one of the architects and leaders of the system is fantastically intelligent – some even have degrees from the University of [mumble]. But every one of the neurons in my dog’s brain is a fantastically complex pinnacle of three billion years of evolution, yet my dog herself can spend the better part of an hour standing motionless, hackles raised, barking at a plastic bag.

To you I don’t have very much advice. I’m no smarter than anyone else – well, I know who Euclid is, but other than that – and if I knew how to fix the system, it’s a pretty good bet other people would know too and the system would already have been fixed. Maybe you, armed with a degree from the University of [mumble], will be the one to help figure it out.

On the other hand, someone a lot smarter than I am did have some advice for you. Poor Kurt Vonnegut never did get to give a real graduation speech, but one of his books has some advice targeted at another major life transition:

Hello babies. Welcome to Earth. It’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It’s round and wet and crowded. On the outside, babies, you’ve got a hundred years here. There’s only one rule that I know of, babies-”God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.”

I don’t know how to fix the system, but I am pretty sure that one of the ingredients is kindness.

I think of kindness not only as the moral virtue of volunteering at a soup kitchen or even of living your life to help as many other people as possible, but also as an epistemic virtue. Epistemic kindness is kind of like humility. Kindness to ideas you disagree with. Kindness to positions you want to dismiss as crazy and dismiss with insults and mockery. Kindness that breaks you out of your own arrogance, makes you realize the truth is more important than your own glorification, especially when there’s a lot at stake.

Here we are at the end of a grinder of $150,000, 20,000 hours, however many dozen collages about The Scarlet Letter, and the occasional locker room cry of “faggot” followed by a punch in the gut. Somewhere in another world, there are people just like us in nice cabins reading Aristotle and knowing that nobody will have to go hungry ever again. The difference between us and them isn’t money, because I think the $155,000 the government gave you could have gone either way – and even if I’m wrong about that there’s more than enough money somewhere else. The difference isn’t intelligence, because the architects of our system are fantastically bright in their own way. I think kindness might be that difference.

Technically kindness plus coordination power, but that’s another speech, and the Dean of Students is starting to make frantic hand signals.

I don’t know if it’s really possible to afford to give everyone that cabin in Colorado. But I hope that the people whose job it is to figure that out approach the problem with a spirit of kindness and humility.

In conclusion, both sides of the sunscreen debate have some pretty good points. It will certainly decrease your risk of squamous and basal cell carcinomas, it probably has no effect on the malignant melanoma rate but there’s a nonzero chance it might either cause or prevent them, and its effect on internal tumors seems worrying at this point but is yet to be backed up by any really firm evidence.

I understand this is complicated and unsatisfying. Welcome to the real world.

[Congratulations to my girlfriend Ozy, who graduates college this week!]

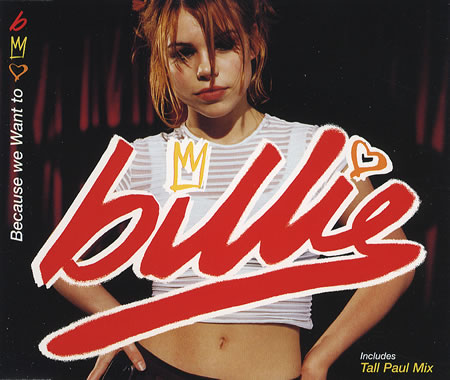

BILLIE – “Because We Want To”

#794, 11th July 1998

Pop Between Realities, Home In Time For TOTP

Pop Between Realities, Home In Time For TOTP

I’ve talked about Dr Phil Sandifer’s TARDIS Eruditorum blog before on Tumblr, but I’ve held off mentioning it here until this post, for hopefully obvious reasons. TARDIS Eruditorum is a critical Doctor Who blog which has been running since 2011 and will end this year. Its format – which Sandifer calls psychochronography – should be familiar to Popular readers: take a cultural object with a long history, and write about it in chronological order. Naturally, writing about the thing ends up meaning writing around the thing. My brother gave me the first three volumes of the book edition of Eruditorum for Christmas, and it was the kick in the arse I needed to really get moving on Popular again.

Eruditorum is tremendous, a mighty achievement. The workrate is boggling, the insight – about a fearsomely well-covered topic – is top-notch, the comments are friendly, the perspective is original. But my favourite thing about it is the structure – the way posts build over weeks, set up recurring concepts, pay off far later, and delight in the formal experiment and play that Sandifer occasionally unleashes within entries. If you don’t like Doctor Who, you might prefer his other epic project – begun last year – a history of British comics from the 1980s on called The Last War In Albion. (Go and look at its Kickstarter, which I’ve backed and might take your fancy too.)

Obviously, narrativisation is something Doctor Who lends itself to more than, say, the charts do, but even so Eruditorum’s narrative is beautifully done, and it’s been a big (and bleedin’ obvious) influence on me this year, not least in demonstrating that a three-posts-a-week workrate gives you a lot more leeway to spread out thematically. Narrativisation is something I’ve resisted doing in Popular, first because it started as an exercise in ignorance (what can I get out of music I know nothing about, without finding anything out?), then because it’s been flitting around and between a well-established story, and demonstrating the arbitrariness of pop success rather than pop’s progress or cohesion seemed far more to the point.

But I’m now getting to the point where existing histories of pop start to drop away. People have talked about what’s happened (or hasn’t happened) in music over the last fifteen years or so, but the stories haven’t quite settled – or at least, the ones that have are often told by more distanced and unsympathetic observers. It certainly isn’t clear that the UK’s number ones are the sensible or right way to tell such stories – Popular will always have more noise than signal – but I’ve found a few good threads to pull on here.

Billie Piper turns out to be a good place to start unravelling one. She is, of course, now more famous for playing Rose Tyler, one of the leads in the revived Doctor Who series. One of the most joyful moments of my dancing, listening, and fannish life was running Club Popular just before the new series began, and Steve Mannion mixing “Doctorin’ The TARDIS” into “Because We Want To”. I’d like to say I always believed Billie would be good, but I honestly had no idea. Whatever she was going to be like, for those five minutes I was totally up for it.

So Billie’s trajectory went from post-Spice pop star to gossip column regular to co-star in the BBC’s most famous show. But it didn’t start there. Before she got a record deal she’d starred in a handful of Smash Hits ads in 1997. Jumping around, scrambling up to the camera, arms swinging, gum blowing, declaring “100% pure pop”. A deal swiftly followed.

Smash Hits in 1997 was not as confident a magazine as its ads suggested. For all that its heyday in the early 80s had seen it bash margins and mainstream together with irrepressible glee and real impact, it had endured a tougher 1990s – successes with Take That and Peter Andre, but harder going in the heyday of Britpop. Now it saw another opportunity: with pop arcing younger, there was territory to claim. Hence the Billie ads – this loping, laughing 15 year old was Smash Hits’ pick as the face of pop.

But what is pop in 1998? What could Billie be the face of? There’s a negative case, put eloquently by commenter Iconoclast in the B*Witched thread:

“this once vital popular art has become commodified, sanitised, neutered, tamed, and bastardised to the level of unthreatening aural wallpaper you can pick up in the supermarket as background music for a dinner party with your parents; in retrospect, this is (probably unwittingly) laying the ground for the eventual Cowellisation (in a broad sense) of popular music, to be lapped up by a compliant and carefully-groomed public who would be baffled by the idea that things could ever have been different.”

Iconoclast represents one broad orthodoxy on pop music in the post-Britpop years. As you might guess, I think this is a bit simplistic – to take one example, while I’m not going to pretend Simon Cowell is remotely a force for good, his influence on pop has been far more contested and complex than “Cowellisation” implies. The rest of pop conspicuously fails to adopt Cowell’s dreary formulae, and his forte lies in building hostile fiefdoms which have a horrifyingly good success rate at launching raids on the charts but leave very little changed in their wake.

That’s getting ahead of myself, though. And just because I reject this radically negative version of pop as a whole doesn’t mean I don’t see where it’s coming from. Things were fundamentally changing, and changing in ways many people would see as a loss. Billie, in fact, is a fine example of this, precisely by virtue of being on Doctor Who. She successfully crossed the tracks between pop star and actor – a notoriously difficult journey that tended to leave pop musicians looking horribly embarrassed. But Billie was a triumph.

So how does she cross these tracks? What Billie Piper had that a lot of previous stars lacked was theatre school training, at the Sylvia Young school (a miserable experience, by her own later account). This is one of the big late-90s pivots in British pop – the point at which stage school really started to become the training ground for a pop career. And to accentuate the shift – though one trend does not cause the other – it happens when the art school tradition that had fed into UK pop since Lennon and Stu Sutcliffe has begun to sputter out, a victim of funding cuts and the end of student grants.

The rise of stage schools following the decline of art schools has an ongoing effect on who gets to be pop stars in Britain, a shift in emphasis that also shapes the critical reception of UK pop music. Critics train themselves to spot and respond to the kind of qualities the art-pop tradition fosters: self-expression, conceptual fluency, executing your ideas well. The story of British pop in the 60s is – partly, at least – the story of people discovering how fantastic an arena pop was for those qualities.

A performing arts education – I apologise for the vast and possibly ignorant generalisations I’m committing here – is set up for slightly different things. Performance, obviously. The discipline and craft to repeat those performances. And the ability to inhabit, interpret and communicate material, deeply and quickly. Pop music should benefit hugely from that stuff too – though almost nobody, whatever their education, gets to be famous in pop while being awful at communicating and performing.

It’s not that one educational tradition is good for pop and that one is bad. It’s not that a stage school background means you won’t be great at the kind of things art school brought to pop. And there’s always a cartload of other things happening outside either. But the rise of performing arts influence was bound to have an impact.

It’s relevant that Sylvia Young pupil Billie Piper got to notch up number ones and then dance over to acting. It used to be that acting was a famously terrible pop move. Now music and acting are both options in a more general entertainment career – the old light entertainment model that worked for Cliff Richard and Adam Faith, back again. But it’s also relevant that Billie, the 15 year old face of pop on TV in 1997, gets to cross from audience to performer so quickly. It suggests an ideal of pop stardom that plays, at least, at being democratic. Pop in the art school tradition was something alien, something that might drop into your world and help you fall out of it. Billie’s version of pop is something you step up and become part of.

Why? How? Because you want to. “Because We Want To” is an awkward if likeable thing, a mash-up of two kinds of teenage autonomy songs. One – mainly in the chorus – is a battle cry of domestic rebellion in all its snotty, petty and essential glory. That’s all about doing what you want, and if it’s pointless and banal to the grown-ups – “why do you hang around in crowds?” – so much the better. The verses song – perfect for a vision of pop meritocracy – is about being who you want, following your dreams. “Some revolution is gonna happen today,” Billie sings, but it’s a positivity revolt, where the battles happen around mood and attitude, “We’re gonna chase the dark clouds away”.

The do-what-you-want song is honestly the stronger one here, probably because it’s a lot older: its roots go back to the Fifties and generation-gap tracks like “Yakety Yak”. It’s hard to go too wrong with snotty teen rebels, however corny and carefully constructed they are. The be-who-you-want song, though, feels more modern – an approach one that’ll really come into its own in the 00s and 10s with Christina Aguilera and Katy Perry. In this form it’s too frothy, though. It can’t build the demolishing momentum it needs, it has to stand back for the other Billie, kicking over bins, stomping her feet and wanting to dance all night. That version is simply more fun.

The devil, unfortunately, is in the execution, particularly the music, which is often the great weakness of theatre school British pop. You can have a charismatic performer, but too frequently there’s an apparent assumption they can settle for second-rate backing. Here it’s the kind of light R&B we saw on the Spice Girls’ “Say You’ll Be There” – already a little dated in 1996, but sold on unexpected touches (the P-Funk, the harmonica) which “Because We Want To” doesn’t deliver. And it’s the part where Billie quotes the Spices where the song falls over hardest, nudging her towards rapping, where she loses any hope of sounding like a force of teenage nature and ends up at a kids’ TV approximation of streetwise. “If you want to catch a ride then GET WITH US!”. As Billie’s predecessor on Doctor Who would have said: wicked, Professor.

Plus ca change...

The same battles are still being fought. We still do not know how the challenge of Russian neo-fascism will be met. We still do not know how the European Union can maintain liberty and democracy in the face of the economic complexities that it has created. We still do not know if the UK can meet the challenge of Scottish separatism. We still do not know how Liberty can be protected in the face of the multiple challenges of technology, fear and greed.

In Britain, tonight is the eve of the European and some local elections, in some of the rest of the EU, the vote is already taking place, although for most the official polling day is on 25th May. Normally I would be out canvassing or delivering for the Liberal Democrats, but a thousand miles away, in Estonia, the challenge of UKIP seems more absurd than threatening. Doubtless the UK media who have been unearthing the ancient scandals of lazy, stupid or incompetent (not to mention racist and not a little dotty) UKIP MEPs during the campaign- well done the Tory attack dogs there- will revert to "government in crisis as UKIP surge" once the results are in. I for my part have already voted- on line of course- in the Estonian EU elections. I wish I could vote for one of the excellent British Liberal Democrat MEPs that are in danger of being ousted by drastically inferior competitors. However, as a permanent resident of Estonia, I have chosen to make a difference here.

In a way the Euro campaign reflects the reality of British politics as a whole. The train wreck of Ed Miliband trying to bluff and bullshit his way out of a trap on BBC Radio Wiltshire was cringe-making and hilarious at the same time. The circus of UKIP has come under sustained attack and Farage too has been revealed as a lying bullshitter. Meanwhile the coalition hunkers down- Cameron hoping to hold his ground and Clegg- who had the nous, but not, alas, the killer instinct, to challenge Farage first- will be hoping to avoid another evening of outright catastrophe. The Liberal Democrats have become the blame hound of British politics, but as I watch honourable and decent candidates stand up for the Liberal vision I feel a certain frustration that the shallow ignorance of the British political discourse is trashing Lib Dem support for mistakes that are more obvious and outrageous in the other parties- not least the nasty and pointless UKIP. The fact is that it is Labour for their incompetence and UKIP for their triviality and greed that should be being punished at these elections.

So, I wish my Liberal Democrat friends and colleagues the best of luck. I think we can limit the damage somewhat this time, and if we do, then I hope that the next few months will see a fairer assessment of the considerable achievements of Liberal Democrats in government.

And anyway, after all, it is never over until the return officer clears his throat!

Newsweek Examines Conspiracy Theories, For a Change

Remember Newsweek? It used to be a news magazine, but they magazined so poorly that they were just a website until recently. They’re back in print, and here’s the latest cover:

(I’d like to point out that the JPG artifacts surrounding the magazine’s name are not from me shrinking the image down. Those are in the image on the magazine’s website, so they’re apparently still committed to quality.)

The cover story is on America’s obsession with conspiracy theories, an obsession I share, except America is obsessed with believing in them. It’s a worthwhile thing to talk about, since it seems like every since issue that comes up for debate is tainted by some kook declaring it the work of the Antichrist, Jews, George Soros, and so forth. The same people who snorted derisively at Hillary Clinton’s “vast right-wing conspiracy” now can’t shut up about the plots and wheels behind Benghazi. Every incident is either something cooked up by one group or a “false flag” cooked up by the other. It’s a poisonous environment where no sensible discussion can emerge.

The media doesn’t help, either, since it loves giving these people a voice. If some nutjob thinks that the American Medical Association joined with ACORN to do the Newtown shootings, we have to bring them on the show and let them holler, or at least admit that they raise a lot of questions.

The Newsweek article talks about all of this, mentioning death panels, Agenda 21, Common Core, and other current darlings of conspiracy lore. But then they say this:

Take the theories about the George W. Bush administration. There have been claims and suggestions that Bush used the 9/11 attacks — or even engineered them — as a pretext to engage in wars and increase the state security infrastructure; that his vice president, Dick Cheney, orchestrated the Iraq War to shovel millions of dollars in reconstruction contracts to his former employer, Halliburton; and that the administration rigged the 2004 election through fraud in Ohio. And while these ideas have been put forward by plenty of regular citizens, they have also been advanced by national political figures: respectively, Keith Ellison, a Democratic congressman; Senator Rand Paul, a Republican associated with the party’s libertarian wing; and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the son of Bobby Kennedy, who is now a liberal radio talk-show host.

Maybe I’m too far gone down the rabbit hole myself, but there’s a huge difference between “Bush did 9/11″ and “Bush and Cheney used 9/11 as a way to get a war they had already wanted in Iraq to happen.” The former is unsupported nonsense. The latter is documented fact. It doesn’t take an unhinged mind and a lot of logical gymnastics to deduce that Bush and Cheney took advantage of the attack to steer sentiment towards the Iraq war. That’s not the stuff of grainy photos, rumors, and smudged Xeroxes, it’s easily verifiable, countable data that we actually were interested in for a brief moment a few years back.

This isn’t just obnoxious and self-serving, it’s dangerous. To deny what actually happened in the lead-up to the Iraq War is to basically say that the story of the time, that we had credible evidence of imminent WMD use, is legitimate. It’s not, and it never was. It wasn’t a case of the CIA cooking the evidence up, it was a case of the CIA being told to cook the evidence up by the White House. Again, this isn’t wild speculation, we have facts on this. It supports the narrative that anyone who supported the call for war (including Ms. Clinton herself) was understandably convinced of a clear and present danger, which was simply not true. Furthermore, dismissing the fact that Bush and Cheney lied and lied some more to get their war done as a mere fairy story for cranks not only lets them off the hook, but it permits further presidents to do the same.

But of course, looking at the evidence of manipulation would reveal just how much of the media, Newsweek included, whenever they weren’t reporting about the reality of Heaven, aided and abetted the White House by breathlessly repeating whatever hysterical absurdities they were told without doing any work — such as, say, journalism — to verify if any of it matched reality. Better still to say, “No, there was no outright falsification and manipulation of information that we both fell for and encouraged.” If there were no perpetrators, then there can’t be any victims or accomplices.

It’s also interesting to see Newsweek reporting on studies of how people who believed Sarah Palin’s “death panels” story reacted when given evidence that such things didn’t exist. Newsweek, and few other media sources, can’t give examples of when they themselves revealed that the “death panels” nonsense was a lie because they have absolved themselves of this duty, instead explaining that if Palin said it, they just have to report it and their work is done. You cannot fault Americans for hanging on to faulty information if you are responsible for disseminating it without question.

You’ll note that when asking where conspiracy theories come from, Newsweek cites the usual: fringe sources, social media, “the Internet”. Certainly not reputable places like Newsweek, who would never, ever do such a thing. They mention “the mass media” and “news outlets” but only in a matter-of-fact way. They also end the article with

So it goes with the endless loop of conspiracy theories. They can’t be corrected, they can’t be killed. Anyone who attempts to disprove some feverish thought must be involved in the plot. Indeed, most of the experts interviewed for this article agreed on one fact: Once it was published, Newsweek would be accused of being part of the conspiracy.

That’s me rolling my eyes at you, Newsweek.

Crashing Down To Earth: Sensory overload and its aftermath

Andrew HickeyThis is one reason why I want our housewarming the day after the election -- so the whole last week and this one can be one massive event that I can then recover from, rather than a series of smaller ones.

It seems there is one lesson I’ll never learn: if it can be helped, don’t plan to do anything after doing something I know will be massively overloading. I mean, I know not to plan to do anything stressful. I’m vaguely grasping the concept of not planning to do anything involving other people. But when it gets really bad, even that blog post I was planning to write and that bit of work I was planning to finish are not going to happen. They won’t happen. Nothing you can do. They just won’t. Do. Not. Plan. Anything.

Generally I get two types of sensory overload (your mileage may vary):

Same reaction, different threshold. For example, jumping at a loud noise that didn’t startle anyone else. Or arriving at the lecture hall and immediately flushing up. The former is over in a split second, the latter is a bit more horrid but still fades away after a few minutes, and both are very quickly forgotten about as I generally get on with life. For me, the main problem here is self-consciousness rather than anything else.

A Huge Draining Longer-Term One. For example, arguments, unpredictable crowds, parties… oh, and that weather I’m trying in vain not to talk about. At least all the other stuff exists in finite spaces for a finite period of time, and can be escaped from. Anyway, this is where my reaction to The Overloading Thing becomes, at least internally, really different from the standard neurotypical not-liking-this-much reaction. There is, somewhere, a threshold at which a meltdown will happen, but luckily I don’t tend to reach it all that often. Throughout The Overloading Thing, I might be coping pretty well; in fact, it’s pretty likely that I’ll still mainly be enjoying the event as a whole, seeing The Overloading Thing as simply a drawback that’s worth it overall. Sometimes I even get used to it and think I’m absolutely fine.

And then I get home. And. I’m. So. So. So. Drained.

As those of you who follow my Twitter and have had to put up with my whining for the past couple of days may know, I don’t handle heat well. I mean, my body is okay; to be fair, this is probably because it’s stuck with a terrified obsessive controlling brain that only lets it out of the shade when it absolutely has no other choice, but I’ve never actually had sunstroke or similar, I vaguely remember dehydration happening on holiday once when I was like 4, and sunburn is very rare too. My brain, on the other hand, just goes all over the place. It’s an sensory overload thing, and then a panicking-about-sensory-overload thing; consequently, it both worsens and is worsened by my other hypersensitivities. I was out all afternoon yesterday at a garden party, and I had a great day, but realistically it was too much people-ing and too much sun (seriously, if you’re doing outdoors-y stuff, make sure there’s a bit of shade, it’s a tiny silly little thing that not many people understand and it’s massively frustrating) to handle in one sitting.

Still, though, I figured after getting in, having a cold shower, putting some cream on the burned shoulder and continuing to underestimate just how much water I am in fact capable of drinking, I’d feel several billion times better and could, well, get on with the aforementioned stuff I’d planned to do. I have a tendency to think “hey, looks like I survived that without a meltdown or a shutdown, hooray for me” and assume I’ll be fine afterwards. I always forget just how much a massive sensory overload, whatever the cause, wipes me out totally. “Tired” doesn’t quite cover it.

Instead, I end up doing, well, not much. Check Facebook. Check Twitter. Check WordPress. Go back to Facebook. There’s nothing new. Scroll down anyway. Put more cream on the relevant shoulder. Stare blankly at Facebook. Think “Okay, so I overdid it”. Think very little else. It’s a state of “nope, that’s it, limit reached, no more input please”. I’ve found that sometimes, for some reason, a little positive input seems to help; despite the many quiet gentle relaxing songs in existence (and, well, the “silence” alternative), last night nothing did the trick quite like this, or this, or this (which is where I got this post’s title from). I have no idea why that is, especially when there are quiet gentle relaxing Muse songs in existence too, but there you go. I even paced around the room a little, which is my standard “MUSIC IS HAPPENING YAY” stim, but perhaps less ideal when you feel like you’ve used up every last drop of energy. Senses are odd. Other than general sensory oddities, though, I tend to just… sort of… want… nothing… to… happen.

Of course, eventually it starts to get better. The only completely reliable “cure” I’ve found is a good night’s sleep; having said that, the vast majority of my Overloading Things are in some way related to big social events, which tend to either take place in the evening or at least go on until then, so that’s probably why. I suppose, eventually, a lot of time to hide away and recover and regulate would have the same effect. In a way, though, it isn’t totally over; most of the time, it gets filed away under “Things That Made You Feel Awful Which You Should Try And Avoid Where Possible In Future”. If something has gone consistently wrong in the past, I guess it’s natural to perceive it as a threat, to worry about it, to plan ahead and specifically go out of your way to avoid it. Even where that’s not always 100% possible. Or 50% possible. Or possible at all. Or possible at all with no firm knowledge of when it will become possible.

No wonder the slightest bit of sun freaks me out so much.

Tagged: actuallyautistic, Autism, sensory overload, sensory processing, the heat thing again

We have no idea how big the peer-to-peer economy is

Etsy.com

The micro-entrepreneurship site Etsy now has a more than a million sellers, individuals — overwhelmingly women — making things like barnwood cutting boards, hand-sewn tea towels and children's toys out of their homes or small manufacturing plants.

You would not get any indication that many of them exist, however, if you looked at government data on traditional jobs and small businesses. Their businesses are so small as to get swept aside by the definitions of the Small Business Administration, which include more than 500 employees and millions of dollars in annual receipts.

"That would put Etsy the company in the same category as our sellers," says Althea Erickson, Etsy's public policy director (yes, Etsy has as public policy director). "That’s crazy."

And the work these people do is either sporadic or so inseparable from personal life that it often doesn't look like a "job." Or a "second job" for that matter.

"They get shoved into the 'bad jobs' or 'bad businesses' frame," Erickson says, "as opposed to being taken on their own terms."

We tend to think these jobs are "bad" -- or not even jobs at all -- because they don't come with benefits, because they seem part-time in nature, because they appear to have popped up in response to a bad economy. And as businesses, we think they're "bad," too, because no one expects the woman who makes custom fire station playhouses to grow into the next Mattel. In fact, according to Erickson, most Etsy sellers don't particularly aspire to become big businesses, or to obtain the credit and investors that might get them there.

These people are, however, doing some kind of work — they're making money and producing something, after all — as are many others in the messy peer-to-peer part of the economy where personal and professional activities now increasingly overlap. But the government hasn't counted what it calls "contingent workers" since 2005. You can tell the government that you're self-employed, or that you have a "second job," or a "part-time job." But it's harder to communicate that while you have a regular job at a coffee shop, and maybe even a temp job on the side, you also make money roughly eight hours a week stitching pillows for sale in your living room while you watch TV.

"If I were to ask the government for one thing, it would be to count this sector better," Erickson says. "I feel like things aren’t real until they’re counted, often."

The Bureau of Labor Statistics' Current Population Survey asks questions like "Altogether, how many jobs do you have?" and "How many hours per week do you usually work at your other job?" But these questions assume that someone who gives a ride on UberX, or runs chores through TaskRabbit, or sells crafts on Etsy considers the activity a "job." They also assume that all work can be counted in hours.

But how would you count the amount of time you spend hosting people on Airbnb, or giving rides in your car when you're already on your way to the grocery store? And it's particularly hard to measure work when the people doing it don't consider themselves making "income" so much as rent or gas money.

Here are some more measurement conundrums: If you're one of these "micro entrepreneurs," how would you decide which parts of your "home office" you can write off on your taxes when the economic activity you do at home involves making bath products in your kitchen? How would you calculate your estimated quarterly self-employment taxes when 90 percent of your earnings come around the holidays?

We are, in sum, looking for answers to several questions: How many people are layering this type of Internet-enabled more nebulous work on top of more traditional labor? If micro-entrepreneurs run the gamut from dabblers to full-time proprietors of a business of one (maybe two), how large is that universe?

Of course, we know that people have been making and selling crafts, and providing small-scale services out of their homes for years. But the marketplace of the Internet -- and the lowered barriers of related services like PayPal and Square -- has turned these activities into something larger, something potentially more viable for many people. Once we know how big of a thing we're talking about, we might begin to ask questions about average earnings and economic impact, about who's doing this as a last resort, and who thinks it's "meaningful work."

"That data is a huge part of what’s missing from the policy conversation," Erickson says, although she defers to others to figure out how the government should pose the questions. "Once you have data to show scale, then people start to say, 'Oh yeah, maybe this is something I should care about, maybe this is something we should start building public policies around.'"

At that point, we can start asking questions about how to enable "micro entrepreneurs," whether they're doing this work because of the crummy economy, or because they'd actually rather make hand soaps at home while hosting tourists than work in a traditional office.

Kenneth Clarke is a liberal Conservative not a Liberal Democrat

This is nonsense.

Clarke is a liberal Conservative - a breed that used to be common, but is not almost extinct. And the Conservative Party is much weaker because of it.

In his early days as leader, it looked as though David Cameron had grasped that, in order to win a majority, his party had to reach out to voters who are not instinctive Conservative voters. And in order to do that, he would have to reverse its rightward drift.

Some even saw the formation of the Coalition as a tactical masterstroke on his part. He had co-opted the Liberal Democrats to take the place of his own party's vanished liberal wing.

Few now see Cameron in those generous terms and Steerpike sounds like a Labour activist from the 1980s saying some moderate MP who refused to back the Militant or Bennite line was a "Tory" who should be thrown out of the party.

The truth is that the Conservative Party, which has not won a majority for 22 years now, needs many more people like Kenneth Clarke if it is to thrive.

Someone’s Going to be an Asshole; Why Shouldn’t it be Me?

By now you’ve heard of the horrific situation in Nigeria, where two hundred girls were kidnapped and probably sold into slavery by a band of Muslim fundamentalists called Boko Haram. The girls’ crime? Trying to get an education, which of course is anathema to any band of religious fundamentalists, since they can’t agree on which is the One True Religion, but they’re all certain that it involves hating women.

The government of Nigeria was content to do nothing until some Nigerian citizens started a Twitter campaign that grew into a worldwide plea: #BringBackOurGirls. This has not only spurred Nigeria into at least acknowledging that a crime took place, but also other countries into offering help. This is literally a moment in which hashtag activism actually helped accomplish something. You’d think that would be a good thing.

You’d also think that this is a political no-brainer. Islamic terrorists kidnapping children? Who in their right mind isn’t going to stand up against that? We as a country have spent the last thirteen years doing whatever we can to fight terrorism. And they’re going after innocent girls! All that’s missing from this scenario is a heads-up display and the ability to switch between weapons quickly and you have all 17 of next year’s best-selling videogames.This is exactly the kind of terror-fighting opportunity you’d think people on both sides of the political aisle would fantasize about.

However.

This image then showed up, Michelle Obama showing solidarity with those seeking justice. And immediately the right wing remembered what they hate more than Islamic terrorists who kidnap innocent women. And they also realized that suddenly they weren’t the center of the discussion, and this also made them furious. So at once they had to lash out, making it clear that while they certainly agreed the Boko Haram actions were horrible, this kind of “lazy activism” instead of “real action” was futile and pointless. Real action such as, I guess, yelling about the Obamas on your radio show.

Ann Coulter even took the opportunity to do her favorite thing: try and get a camera pointed at Ann Coulter.

And, on cue, all the usual morons pumped their fists and started back on Benghazi and Hillary Clinton and all of their usual other nonsense, having been assured that they could — in fact were correct in doing so — ignore this seemingly slam-dunk of a Muslim terrorist situation in favor of their conspiratorial fever-dreams.

Who’s surprised?

I’ve come to realize that there’s a sort of common thread to right wing behavior. You see it when some CEO talks about how sure, he destroyed the pensions of thousands of people to get a few bucks but what he did wasn’t technically illegal. You see it when some blowhard is boasting about how he’s just being honest, just saying what everyone’s thinking, just being a realist and telling it like it is. You see it when someone is talking about how we can’t have a good thing because there are ways it could be exploited for personal gain, and it’s clear they’ve thought about this because it’s exactly what they’d do. You see it when someone complains about the “PC Thought Police” not letting folks bully women, minorities, gay folks, and anyone else they find beneath them. The common thread seems to be:

Someone’s going to be an asshole; why shouldn’t it be me?Someone’s got to talk shit about all these people trying to do what they can about a horrible situation they’re otherwise powerless over. In fact, the very fact that it’s such a monumentally obvious thing to get behind makes it perfect for someone to come “tell it like it is”. After all, if you’re making a lot of people angry, you must be doing something right! And if someone’s going to do it, why not you? You could be that guy doing something right! You could be the one getting attention for your daring, raw, politically-incorrect truth bombs! There’s no situation where someone can’t be an asshole, and man, are people going to pay attention and talk about that asshole, so why shouldn’t it be you?