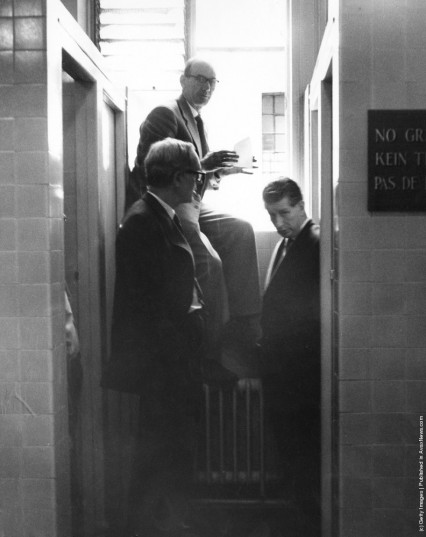

“'You're probably right, but that's not what the public is expecting — this is Hollywood and I want to give people something that's close to what they expect”

-Steven Spielberg to Jacques Vallée

It is named, of course, after J. Allen Hynek's system of classification. Hynek was an astronomer who worked with the United States Air Force as a scientific consultant into their studies into the UFO phenomenon, most famously Project Blue Book. Initially a staunch skeptic, Hynek's views began to change as he investigated more and more and more cases and it became less and less easy for him to discount the credibility of the witnesses he interviewed. After a falling out with the Air Force, Hynek spent the rest of his life investigating UFO cases on a personal basis, and is considering the pioneer of scientific research into UFOs. His famous scale is as follows, in order of increasing high strangeness:

- Nocturnal Lights: Sightings of unexplained lights in the night sky.

- Daylight Discs: Sightings of disc-shaped objects during the daytime.

- Radar-Visual: Confirmed radar hits.

- Close Encounters of the First Kind: A UFO observed less than 500 feet away.

- Close Encounters of the Second Kind: A UFO, sighted less than 500 feet away, with a seemingly discernible physical effect.

- Close Encounters of the Third Kind: A UFO sighted less than 500 feet away, accompanied by sightings of animated beings.

That Steven Spielberg named a movie after Hynek's scale (not to mention casting Hynek himself as an extra in the climactic meeting with the Mothership, along with UFOlogist Stanton Friedman, famous for his interest in the Roswell case) is well known for being the impetus for it becoming ingrained in pop consciousness. But it also reveals the extent to which

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is genuinely indebted to a specific philosophy: Friedman's presence aside, this is not actually a movie about UFOlogy. Indeed, ironically in spite of his influence on the field, Hynek was not what we'd think of today as a UFOlogist and the work he did would likely be met with some suspicion, if not outright scorn, in modern UFOlogy.

No,

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is a movie about spiritualism, childhood, wonder, and the sacred music of the universe. And that makes it pretty much the single most important and powerful work we've looked at so far.

Steven Spielberg, as a creative figure, is often criticized for his fixation on a somewhat vapid notion of “childlike wonder”, and there is something to that. Spielberg has always privileged the child's perspective (or what he perceives a child's perspective to be) and does seem to feel there's something genuinely special about the way children see the world. And certainly it can be argued that starting with

E.T. he begins to dutifully recite these themes as comfortable platitudes film after film. But, in regards to

Close Encounters of the Third Kind in particular, two things really need to be established early on: One, though this is Spielberg's first post-

Jaws work, he's still something of an up-and-coming filmmaker coasting on the latter film's success. At this point, he still very much has something to say and something to prove. And two, Spielberg's interest in childhood, at least in this case, does not come from a place of cloying sentimentality, but from his interest in exploring his own positionality and life experiences.

Steven Spielberg is someone who grew up knowing from a very young age that making movies is all he ever wanted to do. He's the success story every aspiring indie filmmaker dreams of someday being able to emulate. But what this also means is that Steven Spielberg is someone who has a deep, instinctual understanding of images, memories and the power they have over us. It was a confluence of both that compelled a young Spielberg to create the work that became

Close Encounters of the Third Kind when he and his father watched a meteor shower together one night. Some of my earliest and most formative memories are images of the night sky, so I speak from experience when I say I can understand the impact this might have had on someone as creative and imaginative as him.

These images seemed to linger with Spielberg as he made his first commercial movie as a teenager called

Firelight, which was essentially the first draft of

Close Encounters of the Third Kind, incorporating almost all of the same shots and scenes with the exception of having the aliens be malevolent. Six years later, he wrote the short story

Experiences, which tells of a group of teenagers who witness an unexplained light show in the sky one night at the local lovers' lane. It's with

Experiences that Spielberg seems to begin to crystallize what these images mean to him: A group of ordinary, working-class people share something together that changes how they view themselves and their connection to the world by exposing them to the cosmic whole. This is not the pomp and grandeur of religious visions, at least as commonly depicted, this is an intimate moment of soft, gentle beauty that quietly brings them a newfound sense of personal understanding.

Throughout the 1970s, Spielberg developed an interest in the growing fascination with the UFO phenomenon, and initially attempted to pitch either a documentary or a docudrama about it, but was always rejected and, eventually,

Jaws took precedence over anything else. It's this that informs

Close Encounters of the Third Kind as much as anything else, because the 1970s were the true heyday of inexplicata and high strangeness. Although the modern UFO phenomenon as it is usually conceptualized dates to the 1940s and 1950s and thus is more properly seen as a contemporary of the Golden Age of science fiction, with which it ran parallel, it was the 1970s that saw the highest concentration of sightings that form the background of what the field of Forteanism is today.

In April of 1977, the same year

Close Encounters of the Third Kind was released, multiple witnesses claimed to have sighted a pale creature with large eyes and limbs like tendrils haunting the town of Dover, Massachusetts in an event that has come to be known as “The Dover Demon Case” and that launched the cryptozoological and Fortean career of behavioural scientist Loren Coleman. Two years prior to that, John Keel published his landmark work of investigative journalism

The Mothman Prophecies, which retold his firsthand experiences trying to report on a series of bizarre and unexplainable events in Point Pleasant, West Virginia leading up to the collapse of the Silver Bridge, including multiple sightings of glowing, shape-changing lights in the sky, a reported contactee case with a being known as Indrid Cold, the definitive, archetypical Men in Black account and, of course, the titular Mothman: A six-foot tall, black, winged humanoid resembling a headless torso with glowing red eyes where its chest should be and enormous black wings, thought by some to be a spiritual guardian come to warn of impending doom. Although all the Point Pleasant events happened in 1966 and 1967, Keel's book wasn't published until 1975, which is when the story became a mainstream phenomenon.

One year before the publication of

The Mothman Prophecies, in 1973-4, there was a rash of unexplainable events throughout the state of Pennsylvania, including a plethora of UFO sightings that corresponded with sightings of Bigfoot-like creatures with green, glowing eyes who seemed to appear out of and disappear into thin air at will. Cases like these and other such events throughout the 1970s began to blur the lines between conventional UFOlogy, which had long held (and still does) to the “ETH” or “extraterrestrial hypothesis”, (which predictably, claimed that UFOs are spacecraft piloted by advanced visitors from other planets), an attitude which defined the so-called UFO era of the 1940s and 1950s, and Forteanism, a discipline which hadn't been seriously examined in a century.

Named for natural scientist and satirist Charles Fort and his concept of “Damned Data”, Forteanism simply means the scientific pursuit of anomalous and unexplained phenomenon that conventional science doesn't like to soil its hands with and a rejection of the claim made by anyone, even scientists, to posses Ultimate Knowledge. And

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is very much a part of this zeitgeist: Far from being a throwback to Golden Age Hard SF, UFOlogy, Roswellianism and the ETH (despite the UFOs in the movie actually being extraterrestrials),

Close Encounters of the Third Kind takes the tortured, wailing Fortean soul of the 1970s and sets it at ease by combining it with Steven Spielberg's rapturous sense of cosmic oneness and personal memory. There are three key figures here: One, of course, is Spielberg himself. Second is Richard Dreyfuss' character Roy Neary, and third is Jacques Vallée.

A former student of J. Allen Hynek, Jacques Vallée is a computer scientist and astronomer who helped create computer models of Mars for NASA and worked with the early ARPANET experiments, but who is likely most famous for his captivating and controversial theories about the UFO phenomenon. A self-described “heretic among heretics”, Vallée gained fame in the UFOlogy community for providing a credible scientific defense of the ETH...before then going on to completely reject it, or rather to reject its self-assured universal acceptance amongst UFOlogists as being too narrow (how very Fortean).

Drawing on Hynek, Vallée believes that we should be open to the possibility that what we know as the UFO phenomenon could actually be a series of different phenomenon, one of which could be a singular nonhuman intelligence that has existed alongside humanity that adapts different cultural forms, perhaps as part of a shared collective unconsciousness. Vallée was the first researcher to compare modern UFO reports to ancient stories about encounters with faery and travelling to Otherworlds, as described in his book

Passport to Magonia, and to point out the UFO phenomenon has existed practically since the dawn of humanity (his most recent book,

Wonders in the Sky, is a rather staggering work that chronicles

every single UFO sighting of scientific merit *in history* up to the 1880s-I highly recommend it).

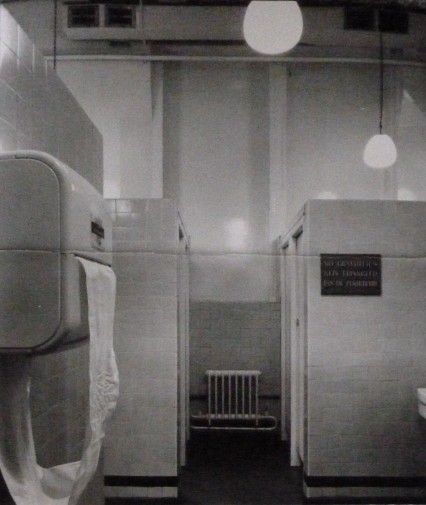

Steven Spielberg was provably influenced by Vallée's work when making

Close Encounters of the Third Kind, because not only did he bring Vallée on as a consultant, he also explicitly based Doctor Lacombe, François Truffaut's character in the film, on Vallée himself. But while Vallée frequently openly wonders about his hypothesized nonhuman intelligence potentially manipulating humans for some unknown and unseen purpose, Spielberg's idealism, and, I'll say it, childlike sense of wonder, prevents him from being that cynical, and

Close Encounters of the Third Kind has all of this in droves. The scene on the hill where the contactees watch the UFOs glide over the road before flying off in formation perfectly conveys a profound sense of cosmic wonder, beauty, love and togetherness, which is mirrored again when Jillian and Roy tearfully watch the aliens greet the humans in the film's final moments. At no point in the movie do the UFOs once feel frightening or threatening: Strange, mysterious and difficult to understand, yes, but never scary. When we see those lights in the sky at night, we feel nothing but an overwhelming sense of joy and kindness.

Spielberg's focus on children is easy to see throughout the film. Barry is the first person who is contacted, and he's the only main character who is never unnerved or confused by what's going on: He simply accepts and understands. The aliens themselves look remarkably childlike too, so it's quite easy to read this as Spielberg saying a child's perspective is the best way to engage with the world and attain higher states of enlightenment. And it's easy from this to launch into the typical criticism of Spielberg, that his focus on childlike wonder embraces naivete and sentimentality at the expense of adult experience. But to do this, we would have to ignore practically everything else about

Close Encounters of the Third Kind: Unlike with

E.T. and Elliot, Barry is manifestly not the protagonist here, Roy and Jillian are (actually, to be perfectly accurate, the protagonist is really probably Lacombe, though the film is really quite good at building an ensemble cast for what it is) and it's not his perspective we're supposed to be paying the most attention to.

Like

Experiences before it,

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is really about the intersection of the greater universe with everyday, working-class people. The mythic with the mundane. This is the most obvious with telephone repairman Roy and single mom Jillian, but none of the other people contacted come from particularly privileged backgrounds either, from the other blue-collar people Roy and Jillian meet on the Indiana-Ohio line to the farmers and nomads in Mongolia, India and the Sonora Desert. Even Lacombe, who is a scientist and spends most of the movie running around with the military, is just someone who wants to understand his place in the universe and is at frequent odds with his ostensible superiors (which mirrors the real life Jacques Vallée's distrust of the military establishment: It was his witnessing of the immediate wiping of record tapes capturing a retrograde satellite while working for the French Space Agency in 1955, a time when no space agency had the means to launch an artificial satellite, that inspired him to take up independent UFO investigation in the first place).

“The sun came out last night. And it sang to me.”

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is sometimes read to have Christian undertones (odd, given Spielberg's Jewish heritage), and there is the slightest hint of pop Christianity about it:

The Ten Commandments comes on television at one point, and the aliens greeting Roy and escorting him into the Mothership looks a bit like angels escorting someone to heaven (Roy's arms are even outstretched, and he has been described as a Moses figure. Yes this, is from the Old Testament, but the iconography on display, especially

The Ten Commandments, is obviously pop Christian).

A few things strike me about this reading: For one, Jacques Vallée would probably point out a lot of things described in the Bible could be read as UFO sightings. Secondly, it's silly to suggest Spielberg didn't know who his audience was in the 1970s United States (Hint: the major's comment when the army is trying to figure out how to evacuate the area around Devil's Tower about “every Christian soul” is a big clue). But what really disabuses me of any pop Christian reading of this movie is its most iconic aspects: Devil's Tower, and those five little notes.

It would be facile to claim that the aliens in

Close Encounters of the Third Kind simply communicate through music, or that music is their language. That's plainly not what's going on: Rather, it's music that both the aliens and the humans recognise as a *universal* form of expression. Recent neurological studies suggest that our reaction to music is largely on the subconscious level, literally resonating with parts of our brain that no other art form can reach. Music is something very primal, and this is once again something mystics have known for centuries. Shamans around the world use music to help enter trance and attain altered states of consciousness, and the Gnostic heretics believe in the concept of

musica universalis, “The Music of the Spheres”, upon which the entire universe is built.

And again, Steven Spielberg understands this: Lacombe and his team travel to India to learn the famous five notes, where the aliens have quite clearly already been. To me, this is one of the most hauntingly powerful and moving scenes, not just in

Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but in all of cinema, as the entire population of an Indian spiritual sect has turned out to chant that indescribably lovely musical sequence at the sky in unison. Spielberg and his team gave us an unabashed Classic Hollywood moment in just about the last moment it was possible to do so. I hear, and

feel that chant, and its powerful sense of understanding, resonate in my mind long after the credits to the actual movie roll.

(Which is not, of course, to discount the more famous synthesizer version at the end: A soft, poignant, gently yearning rendition that's quintessentially Long 1980s and an elegant masterpiece of electronica. I dare you not to cry along with Jillian when you first hear it.)

And furthermore, it provides us with all the material we need to redeem the heavy military focus elsewhere in the movie: It's simply not the case that the US military were the ones who made first contact, in spite of them getting the climactic scene: The aliens came and spoke to people all over the world, and, just as Jacques Vallée felt, each group of people interprets the experience through the lens of their own culture. Which is indeed what happened to Roy and Jillian too, and what

Experiences was trying to get at: It's the same thing William Shatner was trying to tell us on

The Transformed Man-Ultimately, we all have to look within ourselves to work out what enlightenment and the transcendent means to us individually and as communal beings. Imagine a scene as spectacular and wondrous as the Indiana/Ohio line or the climax at Devil's Tower playing out each night to different people all over the world: *That's* what's happening during the cuts in

Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

There is, of course, Devil's Tower itself. The special effects of the scene are of course magnificent: Douglas Trumbull did them, and he also similarly supervised the effects shots on

2001: A Space Odyssey,

Star Trek: The Motion Picture and

Blade Runner, meaning he's pretty much responsible for every one of the most iconic and memorable images from my moviegoing career. I'm constantly awestruck by Trumbull's work: He's an unabashed master at perfectly conveying the most esoteric and indescribable visions and landscapes, which also makes me more than a little jealous of his raw talent. As someone who constantly struggles trying to convey their visions and imaginary worlds in an artistic form, there's not much I wouldn't give for an ounce of Trumbull's skill.

But the power of this moment extends beyond the scene itself: Loren Coleman, an expert in both behavioural patterns and Fortean inexplicata, often points out how places that have certain names (most frequently ones that in some way or another reference devils or faeries) tend to have a much higher concentration and rate of high strangeness than others. Like his frequent nods to the work of J. Allen Hynek and Jacques Vallée, this shows that Steven Spielberg quite evidently did his homework properly. Of course the aliens would point Lacombe's research team to Devil's Tower. And of course, it would be a Tower, a structure that commands a sense of mystery, awe and wonder as it rises from the Earth like a tuning fork or maestro's baton, to tune into the eternal music of the universe.

If

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is indebted to any part of Westernism, it's not pop Christianity, but rather a resurrection of esoteric gnosticism fused with ancient pagan tales of faery-lands and Otherworlds (also note how the people who return from the ship at the end have not aged since they were last seen, just as travellers to the Land of Eternal Summer do not age at the same rate as people in our world do). This is, in fact, a story about ordinary people who have a chance encounter leading them to fall into a whole new world, or rather, who gain the experience and knowledge to understand the harmony between worlds that unites us all together. It's a story about the rediscovery of mysticism, shamanism and enlightenment in the late-capitalism, modernist West, and its trying to tell us such things belong to all of humankind, but especially to the ordinary folks.

It is also true, however, that

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is oftentimes more about the awe one feels at the dawn of such a journey, not the wisdom one learns from undertaking the journey itself. In many was this could be seen as a return to children's literature, and thus another example of Steven Spielberg's “childlike naivete”. But, to borrow from Shigeru Miyamoto, one not need be a child or revert to the mentality of child to understand wonder and joy at experiencing the Cosmic Whole: One merely needs to consciously understand some things that children may know innately and retain that throughout our lives. Always keep learning and growing, but never lose sight of what connects you to your fellow beings and the larger universe. And remember to smile about it, because that's the most joyous feeling of all. If

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is children's literature, it's children's literature for adults, remaining as cosmically profound and moving as it is structurally simplistic. I think we need more things like that.

If that's hopelessly naive and childish, than guilty as charged.

I will submit

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is not *quite* a perfect movie. There are things about it I've always had problems with, and even Steven Spielberg says there are things about it he would change, but I'm actually going to disagree with him on what. Spielberg says that he made the film before he became a father, and had he made it now he would never have let Roy board the Mothership and “abandon” Ronnie and his children. Well, with all due respect to Mr. Spielberg...he's wrong. Ever since becoming a parent, Spielberg has supplanted his themes of childlike wonder with an equally strong emphasis on the importance and responsibilities of fatherhood, the most egregious example I can think of is turning Captain Haddock into a father figure for Tintin in his

Adventures of Tintin movie, which couldn't misread both characters any harder if it tried. I hate to say parenthood ruins people's sense of creativity and imagination...but in this case it kinda did.

The thing is, Ronnie and those kids are *not* Roy's family. That's actually the whole point of their entire role in the movie: Roy didn't “abandon” them,

they left

him because they couldn't understand him and Ronnie in particular simply could not accept that the world was not as neat, orderly and mundane as she wanted to think it was. Just like William Shatner said, enlightenment looks like raving lunacy to the unenlightened, or to those too scared to try for it. Props go to Teri Garr here, by the way, who plays Ronnie as essentially what Roberta Lincoln from “Assignment: Earth” would be like as a housewife, which is as demonstrative of her considerable acting chops as it is somewhat sad, considering two of her three most famous roles are harried, frenzied and ditzy blonde women (and speaking of the original

Star Trek, I have to say I noticed and appreciated Roy's AMT USS

Enterprise and Klingon Battlecruiser mobile). No, Roy's real family is Jillian and Barry, and *that's* where

Close Encounters of the Third Kind actually drops the ball.

The scene at the end where Jillian explains to Roy that she's “not ready” and stays behind to pick up Barry while Roy leaves to join the aliens is basically inexplicable and inexcusable. The entire movie has been building to bringing Roy and Jillian together because of their shared experiences...and

now it splits them up, at the most crucial scene in the whole film? To paraphrase Roy himself, why can't they all go together? Because there's a real sexism here, as it implies Jillian's entire motivation was to look after Barry (which it isn't, but that's the implication of that scene) and this means the movie ends on the really sour note that men can go on transcendent mystical adventures and so can children because of their unique perspective, but women can't because they're too domestic (I know there are women in the military unit that leaves at the end, but why wouldn't you have your

actual heroine among them?). I can forgive Ronnie because being willfully blinkered is part of her character, but there's absolutely no reason or excuse for Jillian not to leave with Roy. In fact, it submarines the entire message of the rest of the film: She had the exact same kind of shamanic experience and is every bit as entitled to it as he is, and furthermore,

they love each other goddammit.

(Incidentally, Teri Garr initially tried out for Jillian's role, which she really wanted and I actually would have liked to see).

There are a few other little things that are maybe less successful than others: Something could be made about the fact that there are fewer nonwhite, non-Western characters depicted as individuals when compared to the Westerners: Mongolia, Mexico and, as brilliant as the rest of the scene ultimately is, India, are all ultimately portrayed as somewhat homogenous and uniform, though there *are* nonwhite, non-Western characters too (most notably the African American air traffic controller in Indianapolis and a few officers in the climactic scene at Devil's Tower). Although that noted, I tend to feel

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is much, much better than Hollywood's usual standards when it comes to this sort of thing and while these inconsistencies should be pointed out, they're nowhere near bad enough to damn the whole film.

Which is actually my takeaway from this movie in general:

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is a profound, moving, inspirational work that should stir the soul of anyone who watches it. It may not be the most comprehensive overview of everything it tackles, but you'd be hard pressed to find a better introduction in the world of mass market Soda Pop Art, especially one that leaves you with more vivid images and more powerful emotions. Coming during Hollywood's last great stab at relevance, its a fitting reminder of the things the cinematic spectacle model could actually do right, and also arguably the last moment where it

did do them right. There aren't many times I truly *get* Hollywood or will praise its overt embrace of spectacle, but as far as I'm concerned

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is without question the pinnacle of what Hollywood can do.

It is, quite simply, the greatest live action science fiction movie of all time.