Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

The Unrecovered (response to the New York Times's "The Kids Who Beat Autism")

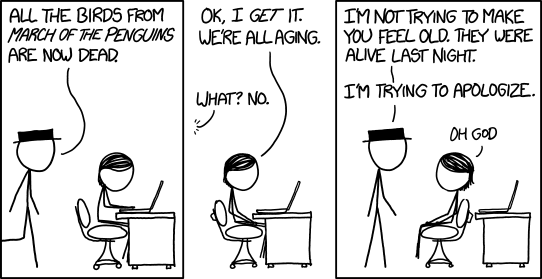

Get Out Your Bingo Card

Meanwhile, somewhere on the Internet, I suspect there’s a tune going on right now that sounds a little something like this.

WE ARE GOING TO MAKE THE HUGO SLATE A REFERENDUM ON THE FUTURE OF SCIENCE FICTION

(loses)

THE HUGOS DON'T MATTER ANYWAY—

John Scalzi (@scalzi) August 17, 2014

I NEVER WANTED THE AWARD THAT'S WHY I'VE WHINED LIKE A KICKED DOG ABOUT IT FOR A COUPLE YEARS RUNNING.—

John Scalzi (@scalzi) August 17, 2014

ITS PROOF THAT ALL THE FEMINISTS NEED TO DO TO WIN AWARDS IS WRITE BETTER STORIES ACCORDING TO THE JUDGEMENT OF THE FANS SHEEESH—

John Scalzi (@scalzi) August 17, 2014

I'VE LEARNED MY LESSON AND MY LESSON IS THAT WE DIDN'T HAVE ENOUGH PATENT RACIST SHITBAGGERY ON OUR SLATE WHAT THAT WAS GOOD WRITING MAN—

John Scalzi (@scalzi) August 17, 2014

AND NOW I WILL IGNORE THE HUGOS AGAIN UNTIL NEXT YEAR WHEN MY FEELINGS OF PASSIVE AGGRESSIVE INADEQUACY ANGRILY WELL UP ONCE MORE—

John Scalzi (@scalzi) August 17, 2014

WHO IS CALLING ME PASSIVE AGGRESSIVE I AM ALL AGGRESSIVE DON'T YOU SEE THIS HUGE GUN I HAVE WITH ME AT ALL TIMES

(breaks down, sobbing)—

John Scalzi (@scalzi) August 17, 2014

SHUT UP I AM NOT CRYING IT'S THAT LITTLE FLECKS OF GUNPOWDER FELL INTO MY EYEBALLS SOMEONE GET ME A FLAMING SWORD SO I CAN FLICK THEM OUT—

John Scalzi (@scalzi) August 17, 2014

RT @wilw: @scalzi don't forget the obligatory "IZ ALL A LIBRUL CONSPIRACY SHEEPLE HUSSEIN OBAMA" stuff.—

John Scalzi (@scalzi) August 17, 2014

I am now done channeling Angry Rationalizing Hugo Losers. If you want more, you'll have to go to the actual source. You have fun with that.—

John Scalzi (@scalzi) August 17, 2014

As they say, bless their hearts.

Third Way-ism and Hegel’s Bluff

“Third Way” people are mean. And they’re proud of it.

I’m speaking arithmetically, which is how these folks seem to approach the world. Take any two sides of a dispute, add them together and divide by two. That’s the average, the mean, and that’s your “Third Way.”

That’s an elegant approach to answering all questions and resolving all disputes. Provided, that is, that every dispute involves two and only two sides, each of which is wrong in precisely equal measure.

I can’t think of any non-mathematical examples of such a dispute between perfectly binary equivalents,* but I suppose it’s possible that there might be some. And in those cases, I suppose, the “Third Way” ideology might be something other than an odious exercise in self-congratulation and a refusal to listen or learn.

But most of life isn’t like that. Most of the time we don’t find ourselves uniquely positioned to ascertain the truth about which everyone around us is obviously and equally wrong.

Most of the time, when someone invokes a “Third Way,” they’re simply committing Hegel’s Bluff:

Simply find two extreme views roughly equidistant from your own along whatever spectrum you see fit to consult. Declare one the thesis and the other the antithesis, and your own position the synthesis. Without actually having to defend your own position, or to explain the shortcomings of these others, you can reassure yourself that you are right and they are wrong. Your position, whatever its actual merits, becomes not only the reasonable middle-ground and the presumably correct stance, but the very culmination of history.

Hegel’s Bluff is usually an exercise in self-reassurance. It’s a way of telling oneself that one is being reasonable. It works for that, well enough — well enough, that is, that Third Way-ers applying this bluff seem genuinely confused when others fail to perceive them as being as eminently reasonable as they perceive themselves.

But persuading others isn’t really what the Third Way of Hegel’s Bluff is designed to do. It rarely persuades. It fails to offer a persuasive argument mainly because it fails to offer any argument at all. That’s not really what it’s for. Arguments are made in support of particular conclusions, but this bluffery is more about just trying to reach that state in which any given dispute is concluded. That’s what it values most — that the unsettling argument be settled, not that it be resolved. It’s more about conflict-avoidance than about conflict resolution.

Having said all of that, please don’t misunderstand me as saying that no truth can ever be found “somewhere in the middle.”**

I’m sure some truth can be found there, even when this “middle” is carefully undefined (the middle of what?) and even when it is defined in the most self-serving manner possible (as in Hegel’s Bluff). Sometimes, the truth — or, more humbly, a better approximation of truth — can indeed be found in “the middle,” but that is not because it is in the middle. It’s location in some actual or imagined “middle” is not what makes it true.

Ancient cosmology argued that the Earth is flat and the sky is solid. Modern science disagrees. The truth is not somewhere in the middle.

- – - – - – - – - – - -

* Mathematical examples are easy. Side 1 says that 2+2=5. Side 2 says that 2+2=3. The Third Way proposes, instead, that we seek a reasonable compromise and conclude that 2+2=4.

That arrives at the correct answer, but it does so for the wrong reasons. It cannot know why that correct answer is actually correct other than that it is equidistant between two alternative answers that coincidentally and conveniently just happen to both be wrong to precisely the same extent. Radicalize either of the incorrect views even slightly — Side 1 says that 2+2=5.1 — and this arbitrary formula will produce an incorrect result which the Third Way devotee will have to accept and affirm. They will assert that “2+2=4.05,” without having any way of knowing why this is wrong or even of knowing that it could be wrong.

This is why Third Way-ers can be so easily manipulated by rhetorical “Overton’s Window” games.

This formulaic mathematical approach also helps to understand why it is that Third Way types never seem to fully comprehend either of the antithetical sides to which their Third Way is the culmination of Truth and History. Both of those “sides” — and they’ll only allow for the existence of two, remember — must be revalued in order for the formula to work. That formula works backwards from its purported conclusion, X: X = (a + b)/2.

Reconstituting the two (and only two) sides of any dispute so that their value can be rendered as precisely “a” and “b” tends to involve a great deal of rounding down or rounding up or caricaturing or misrepresenting.

** Here is an odd thing that distinguishes “Third Way” devotees from everyone else: When they arrive at the middle, they conclude that they have arrived. That’s not really how these spatial metaphors work. If we redefine “the middle” as our end-point destination, then it’s not actually the middle, is it? That would shift the true middle to some prior mid-point between that final “middle” and wherever it was one started. We thus wind up creating a kind of Zeno’s Paradox, with an infinite number of middles and, thus, an infinite number of Third Ways.

Lord Bonkers' Diary: An inflatable Julian Huppert

Not liking the sound of this Data Retention and Investigatory Powers Bill - "I am a Liberal and I am against this sort of thing," as my old friend Clarence “Frogman” Wilcock used to say – I attend a Westminster press conference where Clegg is explaining his support for it. I turn up early to be sure of a good seat, and who should I find arranging the stage set but his special advisers Freddie and Fiona?

They are taking turns with a bicycle pump, attempting to get some air into a large balloon that has had a collection of bristles stuck on it. “Whatever is that, you two?” I ask. “It’s an inflatable Julian Huppert,” they explain. “Because everyone is being so unfair about Nick and seems to love Julian, we thought we would bring this along so Nick can hide behind it when he makes his case today. But it seems to have a slow puncture.”

Just then the pump parts company from the valve in the inflatable Huppert, which proceeds to deflate with an all too familiar sound. “I am afraid you have Julian down,” I observe. “Though, come to think of it, perhaps he has let himself down?”

Lord Bonkers was Liberal MP for Rutland South West 1906-10.

Previously in Lord Bonkers' Diary:

Lord Bonkers' Diary: Spotting a wrong 'un

One of the things I have acquired in my long experience of business and politics is the ability to spot a wrong ‘un. George de Chabris, Allen Stanford, Bernie Madoffwithallyourmoney… I wasn’t taken in by any of them. There are more poisonous varieties of wrong ‘un, of course, which is why Cyril Smith was one of a number of politicians, such as [names redacted on solicitor’s advice], whom I never allowed to visit the Home for Well-Behaved Orphans.

Really, I should have smelt a rat the first time I met him, as he and his mother were huddled around the hearth of their terraced house in Rochdale, burning postal votes to keep warm. This was against any number of electoral laws (not to mention the Clean Air Act), but I have to confess I was impressed that every one I saw had been cast for the opposing candidate.

Lord Bonkers was Liberal MP for Rutland South West 1906-10.

Previously in Lord Bonkers' Diary:

Burdens

[Content note: Suicide. May be guilt-inducing for people who feel like burdens. All patient characteristics have been heavily obfuscated to protect confidentiality.]

The DSM lists nine criteria for major depressive disorder, of which the seventh is “feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt”.

There are a lot of dumb diagnostic debates over which criteria are “more important” or “more fundamental”, and for me there’s always been something special about criterion seven. People get depressed over all sorts of things. But when they’re actively suicidal, the people who aren’t just gesturing for help but totally set on it, they always say one thing:

“I feel like I’m a burden”.

Depression is in part a disease of distorted cognitions, a failure of rationality. I had one patient who worked for GM, very smart guy, invented a lot of safety features for cars. He was probably actively saving a bunch of people’s lives every time he checked in at the office, and he still felt like he was worthless, a burden, that he was just draining resources that could better be used for someone else.

In cases like these, you can do a little bit of good just by teaching people the fundamental lesson of rationality: that you can’t always trust your brain. If your System I is telling you that you’re a worthless burden, it could be because you’re a worthless burden, or it could be because System I is broken. If System I is broken, you need to call in System II to route around the distorted cognition so you can understand at least on an intellectual level that you’re wrong. Once you understand you’re wrong on an intellectual level, you can do what you need to do to make it sink in on a practical level as well – which starts with not killing yourself.

As sad as it was, Robin Williams’ suicide has actually been sort of helpful for me. For the past few days, I’ve tried telling these sorts of people that Robin Williams brightened the lives of millions of people, was a truly great man – and his brain still kept telling him he didn’t deserve to live. So maybe depressed brains are not the most trustworthy arbiters on these sorts of issues.

This sort of supportive psychotherapy (ie “psychotherapy you make up as you go along”) can sometimes take people some of the way, and then the medications do the rest.

But sometimes it’s harder than this. I don’t want to say anyone is ever right about being a burden, but a lot of the people I see aren’t Oscar-winning actors or even automobile safety engineers. Some people just have no easy outs.

Another patient. 25 year old kid. Had some brain damage a few years ago, now has cognitive problems and poor emotional control. Can’t do a job. Got denied for disability a few times, in accordance with the ancient bureaucratic tradition. Survives on a couple of lesser social programs he got approved for plus occasional charity handouts plus some help from his family. One can trace out an unlikely sequence of events by which his situation might one day improve, but I won’t insult his intelligence by claiming it’s very probable. Now he attempts suicide, says he feels like a burden on everyone around him. Well, what am I going to say?

It’s not always people with some obvious disability. Sometimes it’s just alcoholics, or elderly people, or people without the cognitive skills to get a job in today’s economy. They think that they’re taking more from the system than they’re putting in, and in monetary terms they’re probably right.

One common therapeutic strategy here is to talk about how much the patient’s parents/friends/girlfriend/pet hamster love them, how heartbroken they would be if they killed themselves. In the absence of better alternatives, I have used this strategy. I have used it very grudgingly, and I’ve always felt dirty afterwards. It always feels like the worst sort of emotional blackmail. Not helping them want to live, just making them feel really guilty about dying. “Sure, you’re a burden if you live, but if you kill yourself, that would make you an even bigger burden!” A++ best psychiatrist.

There is something else I’ve never said, because it’s too deeply tied in with my own politics, and not something I would expect anybody else to understand.

And that is: humans don’t owe society anything. We were here first.

If my patient, the one with the brain damage, were back in the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness, in a nice tribe with Dunbar’s number of people, there would be no problem.

Maybe his cognitive problems would make him a slightly less proficient hunter than someone else, but whatever, he could always gather.

Maybe his emotional control problems would give him a little bit of a handicap in tribal politics, but he wouldn’t get arrested for making a scene, he wouldn’t get fired for not sucking up to his boss enough, he wouldn’t be forced to live in a tiny apartment with people he didn’t necessarily like who were constantly getting on his nerves. He might get in a fight and end up with a spear through his gut, but in that case his problems would be over anyway.

Otherwise he could just hang out and live in a cave and gather roots and berries and maybe hunt buffalo and participate in the appropriate tribal bonding rituals like everyone else.

But society came and paved over the place where all the roots and berry plants grew and killed the buffalo and dynamited the caves and declared the tribal bonding rituals Problematic. This increased productivity by about a zillion times, so most people ended up better off. The only ones who didn’t were the ones who for some reason couldn’t participate in it.

(if you’re one of those people who sees red every time someone mentions evolution or cavemen, imagine him as a dockworker a hundred years ago, or a peasant farmer a thousand)

Society got where it is by systematically destroying everything that could have supported him and replacing it with things that required skills he didn’t have. Of course it owes him when he suddenly can’t support himself. Think of it as the ultimate use of eminent domain; a power beyond your control has seized everything in the world, it had some good economic reasons for doing so, but it at least owes you compensation!

This is also the basis of my support for a basic income guarantee. Imagine an employment waterline, gradually rising through higher and higher levels of competence. In the distant past, maybe you could be pretty dumb, have no emotional continence at all, and still live a pretty happy life. As the waterline rises, the skills necessary to support yourself comfortably become higher and higher. Right now most people in the US who can’t get college degrees – which are really hard to get! – are just barely hanging on, and that is absolutely a new development. Soon enough even some of the college-educated won’t be very useful to the system. And so on, until everyone is a burden.

(people talk as if the only possible use of information about the determinants of intelligence is to tell low-IQ people they are bad. Maybe they’ve never felt the desperate need to reassure someone “No, it is not your fault that everything is going wrong for you, everything was rigged against you from the beginning.”)

By the time I am a burden – it’s possible that I am already, just because I can convince the system to give me money doesn’t mean the system is right to do so, but I expect I certainly will be one before I die – I would like there to be in place a crystal-clear understanding that we were here first and society doesn’t get to make us obsolete without owing us something in return.

After that, we will have to predicate our self-worth on something other than being able to “contribute” in the classical sense of the term. Don’t get me wrong, I think contributing something is a valuable goal, and one it’s important to enforce to prevent free-loaders. But it’s a valuable goal at the margins, some people are already heading for the tails, and pretty soon we’ll all be stuck there.

I’m not sure what such a post-contribution value system would look like. It might be based around helping others in less tangible ways, like providing company and cheerfulness and love. It might be a virtue ethics celebrating people unusually good at cultivating traits we value. Or it might be a sort of philosophically-informed hedonism along the lines of Epicurus, where we try to enjoy ourselves in the ways that make us most human.

And I think my advice to my suicidal patients, if I were able and willing to express all this to them, would be to stop worrying about being a burden and to start doing all these things now.

An Iron Curtain Has Descended Upon Psychopharmacology

Imagine if a chemist told you offhandedly that the Russians had different chemical elements than we did.

Here in America, we use elements like lithium and silicon and bismuth. We have figured out lots of neat compounds we can make with these elements. We’ve also figured out useful technological applications. Lithium makes batteries. Silicon makes computer chips. Bismuth makes pretty gifs you can post on Tumblr.

The Russians don’t use any of these. They have their own Russian elements on their own Russian periodic table, with long Russian names you can’t pronounce. Apparently some of these also have useful technological applications. One of them is a room temperature superconductor. Another improves the efficiency of dirigibles by 500% for some reason.

No one in America seems remotely interested in any of these Russian elements. Many American chemists don’t even know they exist, even though each element has its own English-language Wikipedia page. When informed, they just say “Yeah, the Russians have lots of stuff,” and leave it at that.

American research teams pour millions of dollars into synthesizing novel elements in order to expand their periodic tables and the number of useful compounds they can make. If anyone suggests importing and studying some of the Russian elements, the chemists say “Huh, that never occurred to us, maybe someone else should do it,” and go back to spending millions of dollars synthesizing entirely novel atoms.

If a chemist told you this, you would think they were crazy. Science, you would say, is science everywhere. You can’t have one set of elements in Russia and another in the US, everyone would work together and compare notes. At the very least one side would have the common decency to at least steal from the other. No way anything like this could possibly go on.

But as far as I can tell this is exactly the state of modern psychopharmacology.

Consider anxiety. I would kill for a good anti-anxiety drug. Right now my choices are pretty limited. Benzodiazepines and barbituate work great but are addictive and dangerous. SSRIs work okay but need a month to take effect. Neurontin, Vistaril, and Buspar are safe, fast-acting, and totally ineffective. And Lyrica is expensive and off-label. As a result, a lot of my anxious patients tend to stay anxious.

Any textbook, database, or lecture you care to check on anti-anxiety medications will list the ones I just listed above plus a couple of others I’m forgetting.

But if you look the matter up on Wikipedia, you see all these weird names like mebicarum, afobazole, selank, bromantane, emoxypine, validolum, and picamilon. You can show these names to your psychiatrist and she will have no idea what you’re talking about, think you’re speaking nonsense syllables. You can show them to the professor of psychopharmacology at a major university and your chances are maybe like 50-50.

These are the Russian anti-anxiety drugs. They seem to have pretty good evidential support. Wikipedia’s bromantane article gives a bunch of studies of bromantane in the footnotes, including a randomized controlled trial in the forbiddingly named Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova.

And look what else Wikipedia’s bromantane article says:

Study results suggest that the combination of psychostimulant and anxiolytic actions in the spectrum of psychotropic activity of bromantane is effective in treating asthenic disorders compared to placebo. It is considered novel having both stimulant and anti-anxiety properties.

Imagine reading about a Russian element on Wikipedia, and at the end there’s this paragraph saying “By the way, this element inverts gravity and has to be tied to the ground to prevent it from falling upwards”. An anxiolytic stimulant is really really cool. But somehow generations of American psychopharmacologists must have read about bromantane and thought “No, I don’t think I’ll pay any more attention to that.”

My guess is the reason we can’t prescribe bromantane is the same reason we can’t prescribe melatonin and we can’t prescribe fish oil without the charade of calling it LOVAZA™®©. The FDA won’t approve a treatment unless some drug company has invested a billion dollars in doing a lot of studies about it. It doesn’t count if some foreign scientists already did a bunch of studies. It doesn’t count if millions of Russians have been using the drug for decades and are by and large still alive. You’ve got to have the entire thing analyzed by the FDA and then rejected at the last second without explanation (yes, I have just been reading Marginal Revolution’s review of Innovation Breakdown: How the FDA and Wall Street Cripple Medical Advances; I do need to check out the actual book). Absent an extremely strong patent on the drug there’s no reason a drug company would want to go forward with all of this. I don’t know what the legalities of buying Russian drug rights from Russian companies are, but I expect they’re complicated and that pharmaceutical companies have made a reasoned decision not to bother.

Given this situation, it’s perfectly reasonable for doctors not to prescribe them. Certainly I don’t plan to prescribe any Russian drugs when I get my own practice. Imagine if a patient gets liver failure on one – and remember that people are getting liver failure all the time for random reasons. The patient’s family decides to sue and I’m stuck defending my decision in court. “Yes, Your Honor, I admit I told the deceased to buy a medication no other psychiatrist in the state has ever heard of from a sketchy online Russian pharmacy. But in my defense, there was a study supporting its use in Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. Which I didn’t read, because I don’t speak Russian.”

Everyone follows their own incentives perfectly, and as a result the system as a whole does something insane. Classic multipolar trap.

Luckily, this hasn’t stopped a lively gray market trade in these chemicals, which I totally one hundred percent approve of. Noopept, for example, is a prescription drug in Russia but is sold over-the-counter by online suppliers here. You can even get some bromantane for two bucks a pill.

Don’t worry. I’m sure these people are on the level. How could a site with a background like that possibly be unreliable?

PSA prostate screening is inaccurate and a waste of money.

CHEF – “Chocolate Salty Balls”

#809, 2nd January 1999

Every so often on Popular I hit a knowledge gap that there’s simply no way of talking around, and this is one. I have only ever seen one episode of South Park, after the pub one night, sometime in its first flush of success. I didn’t like it enough to watch more, and that turned out to be it for me and the show – this single aside. If you want a comment on South Park, how “Chocolate Salty Balls” fits into it, its cultural significance – well, the box is open, and I know a lot of the writers here are fans.

Every so often on Popular I hit a knowledge gap that there’s simply no way of talking around, and this is one. I have only ever seen one episode of South Park, after the pub one night, sometime in its first flush of success. I didn’t like it enough to watch more, and that turned out to be it for me and the show – this single aside. If you want a comment on South Park, how “Chocolate Salty Balls” fits into it, its cultural significance – well, the box is open, and I know a lot of the writers here are fans.

With that large and necessary context torn out, what independent life can this song have? Quite a lot. It’s the first outright comedy record to get to #1 since “The Stonk”, but the gap in care, structure and wit between the songs is colossal. There’s none of the soul-shrivelling forced bonhomie of Red Nose Day about this record, where you herd the comics of the day into a studio and pray something half-funny emerges. This is a return to a seventies model – funny songs that got to Number One because they made people laugh.

Except it was never quite so simple. The wheels of the chart require constant greasing, and the applicator here is DJ Chris Moyles, who made “Chocolate Salty Balls” his cause. The last time I touched on the unheavals of Radio One, during Britpop, the station was emerging from Matthew Bannister’s cultural purge. Out went the populist, roadshow-ready entertainer DJs; in came a gaggle of cool kids who knew a bit about music. Gone was the notion that wonderful Radio 1 would be the jolly backbone of Britain’s working day – instead it would move into a tastemaker role, shepherding new trends into the mainstream.

The long-term consequences of this play out across the 00s, but with Britpop at least the strategy seemed to work beautifully. But Britpop faded, and the brash post-Spice wave of tweenpop was exactly the sort of thing the new, cool, Radio 1 struggled with. Bannister’s remade station, you felt, had not really planned on what to do with music it didn’t instinctively like. The old Radio 1 had no such scruples.

And meanwhile, Moyles had emerged as the station’s rising star, very much along the old populist lines – entertainment and banter first, music second, though with a slightly hipper, crueller edge. Promoted to the drivetime show in October 1998, he wanted to foster a big smash, make an impact. Comedy records and hit-hungry DJs had been a regular fit back in the 1970s: they could be again – particularly a record from a show which, like Moyles himself, bounced along on a rep for political incorrectness.

That was one big difference between the old station and the new: the new one could embrace smutty records – if they came from a fashionable source – where the old one huffed and hummed and banned them. And so it was that the national pop station threw its tastemaking weight behind a song whose chorus – and main gag – is a guy singing “suck on my balls, baby”.

Back in the 70s heyday of the comedy record, that wouldn’t just have been unthinkable, it would have ruined the joke. In the days of Judge Dread (“It’s little boy blue with his horn”), the point wasn’t the dirt, it was sneaking it into a public space – like the charts – and sniggering as that space tried and failed to throw it back out.

“Chocolate Salty Balls” can’t rely on that frisson of subversion, even if Chris Moyles might have bristled at the idea he was part of an establishment now. Fortunately, it gets to rely on being funny instead. The central gag – cooking song turns sexual – isn’t just done with panache and left, it’s reinforced by two other, even better ideas. The first is that Parker and Stone know that if you’ve got Isaac Hayes doing your innocent-song-becomes-sex-jam running gag, you use him – so the “recipe instructions” verse of the song is gloriously, creamily over-the-top even without the innuendo (“a touch of va-NILL-uh”) and the music is robustly enjoyable pop funk in its own right.

And the second is that having flipped the cooking metaphor into the sex one, “Chocolate Salty Balls” collapses it back again, paying off the straight-faced tone with the “on fire” gag. It wouldn’t do to overstress the cleverness here – in the end, this is mostly about keeping the promise of a South Park record called “Chocolate Salty Balls” – but having a trick to end on is like knowing how to end a sketch well. It’s basic, but it’s seemed beyond almost every other comedy record we’ve dealt with.

#1052; In which Secrets are shared

It’s Been a Difficult Week (Note: It is Tuesday.)

Yesterday I was going to post about Broadchurch, the British drama we finished watching this past weekend. The Michael Brown news put the kibosh on that, as it seemed tasteless to talk about fictional murdered white kids when there was a real murdered black kid who needed talking about. But not by me; the last thing this situation needed was a white nerd man pontificating on it. That story hasn’t gotten any better, and in fact just keeps getting worse.

Then, last night, came the news that Robin Williams had died, apparently by his own hand. The simple death of Williams is a weird thing. He’s certainly an icon of my generation, and I loved him on “Mork and Mindy”, but he and I parted ways soon afterwards. I occasionally saw movies he was in, but I went more toward George Carlin for comedy.

The suicide following depression thing, well of course that hits home. We’re going to get deluged with “tears of a clown” and “I am Pagliacci” stuff over the next few days, as we learn all over again, as we do each time, that sometimes even very funny and seemingly happy people are hiding a wealth of internal pain. But we’ll forget it soon enough and go back to how depression isn’t a really real thing and you just need to cheer up and antidepressants are evil emotion-destroying poisons and all you really need are Natalie Portman and The Shins.

I feel hollowed out by all this. Last night on Twitter this Achewood comic was going around and I joined in because it was so apt. And this isn’t just the Robin Williams thing, it’s also the Mike Brown thing. We’re all fighting and trying our damndest just to exist. Just to make it to the next day. It’s the only game in town and you can’t win.

Newsnight 101 (Or: trans folk are not perfoming seals)

As many will be aware, mainstream media outlets ran segments on trans issues yesterday following the news that former boxing promoter Kellie Maloney had transitioned. Trans people were invited to appear on both national and local radio and TV shows, and I know Paris Lees in particular had a very hectic day. In general, coverage was positive and the positivity was often from unexpected sources such as the tabloid press.

The BBC did, as is sadly increasingly the case with their coverage of trans issues, fail badly with their use of appropriate terminology and pronouns. The worst offender was Newsnight, which had booked Paris Lees and Fred Dash to appear. They then also asked someone holding transphobic views to appear and both Paris and Fred, being wise to how these things worked, decided to pull out. As the person concerned has stated very publicly that they wanted to debate trans folk getting access to toilet facilities, and that Julie Bindel reported that she was asked on to discuss “whether there is such a thing as a ‘female brain’ and gender essentialism” (Code for “debating if trans people are really just mentally ill?”) this definitely was the right decision.

But given some of the negative narrative I have seen today on Twitter, I thought a little reminder of some basic principles was in order:

Psychology 101: You can be a member of a group and still hold views oppressive to that group. In particular, the view that trans folk should be denied access to gender-appropriate facilities is a transphobic view that leads to events such as people being sexually assaulted. Just because it is a trans person is expressing that view does not magically mean it is not transphobic.

Politics 101: If you engage in discussion on a topic in front of people, you put it in their minds that it’s a topic that has not been settled. Thus, debating access to toilets on Newsnight puts it into the minds of hundreds of thousands of members of the public that it’s still something they can deny to trans folk, because they think it’s not been sorted out already. And Newsnight is regarded as a leader by some, so where they go others will follow.

No, thanks. Trans rights will progress much faster if we don’t go round in circles, endlessly having that debate. It is not as if the trans community has been lacking in other more positive coverage over the last 72 hours and reaching many more people than Newsnight would.

And I have saved the rant for last…

Equality 101: How is it acceptable to demand that anyone, particularly a member of a marginalised group, turn up and debate something on your terms as if they were circus animals? Worse, labeling their refusal to play nicely as oppressing free speech, “aggressive” (As Caroline Criado-Perez, the ten-pound note lady, did) or “intolerant” (As the editor of Newsnight did) really highlights how some people are utterly terrified that a previously oppressed group might finally be gaining some say in their own futures.

A few thoughts on UKIP vote shares and their chances in 2015

Writing on the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog, Steven Ayres looks at where UKIP’s vote came from in the 2014 local elections, and what this might mean in next year’s general election.

Writing on the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog, Steven Ayres looks at where UKIP’s vote came from in the 2014 local elections, and what this might mean in next year’s general election.

It’s an interesting piece, but it brings me back a thought I’ve had recently with regard to UKIP’s chances next years and whether analysis is factoring in the effects of differential turnout and the motivation to vote of UKIP voters.

One assumption that we tend to make in projecting local election results forward to a general election is that the different turnout at the two elections can be ignored as a factor. We know that general elections have larger turnouts that local elections, but we assume that the voters who turn out at local elections are a proportional sample of the voters who’ll turn out at the general election. As an example, imagine a constituency with four parties where 20,000 people will vote at a general election, but only 10,000 of those will vote at the preceding local election. At that local election, we get the following result:

The tendency is to assume that the percentages of votes received in that election represent the share of opinion amongst the wider electorate and that thus amongst the general election electorate of 20,000 Party A will have 8,000 voters (40%), Party B will have 6000 voters (30%) etc. We assume that the 50% who will turn out for the local election is drawn equally from the parties – a Party A voter and a Party D general election voter both have a 50% probability of voting in the local election.

The reason I’m writing this in relation to UKIP votes is that it seems to me that projections of what UKIP might do in 2015 assume that their voters turned out at the same rate in 2013 and 2014 as did supporters of the other parties. I’d need to go back to some of the polling from before May’s elections to confirm this, but my recollection is that it showed UKIP supporters were much more likely to intend to vote than those of other parties.

To go back to the example, we assume it represents voter intention amongst the wider population, but what if each party’s supporters had a wildly different likelihood to vote at local elections? For example, if Party A’s supporters were 80% likely to vote at local elections, while Party D’s were only 20% likely, both could actually have 5,000 supporters amongst the general population. Extrapolating a general election result from a local one when the parties have had differing levels of turnout is not going to produce accurate forecasts.

To return to the UKIP question, one thing I have noticed is that while they have had relatively high percentages in some elections, they’ve not gone beyond around x% of the total electorate. By my calculation, the share of the electorate UKIP have got in high-profile elections recently is:

My suspicion – and it’d take a lot of time with a lot of polling and election data and a stats package to explore that in more depth – is that UKIP’s peak support within the electorate is somewhere around 15%, but they are much more likely to turn out at all elections than voters for the other parties are. Thus, in elections with a lower turnout, their higher propensity to vote and our tendency to assume that those elections are a mirror of voters as a whole makes them look more of a threat in the general election than they will actually be. However, in a general election with turnouts of over 60%, it’s very hard for a party that can’t get more than 20% of the electorate to win a seat. That would require winning a seat with 33% of the vote or less, and while that’s possible, it’s very rare.

UKIP’s dilemma for next year is that their best chance of winning seats comes if a) there’s a low overall turnout in a seat, allowing the higher motivation of their voters to be a factor and b) there are multiple parties competing for a seat, thus making it possible to win with a low share of the vote. However, seats with strong competition between multiple parties are unlikely to have a low turnout because of the amount of campaigning that’s done in them. It seems that UKIP are very good at getting out the vote, but they’ll need to broaden the number of people willing to vote for them to have a serious chance of winning a Westminster seat.

I am pleased the party will take no further action against David Ward

The Liberal Democrats have said they will take no further action against a Yorkshire MP who suggested he would have fired rockets into Israel.

Bradford East MP David Ward faced the prospect of party disciplinary measures after he took to social media site Twitter to support Palestinians in the Gaza conflict.

Mr Ward had said: “The big question is - if I lived in Gaza would I fire a rocket? -probably yes.”

Now Lib Dem chief whip Don Foster has said no further action will be taken after Mr Ward apologised for any offense (sic).I am pleased to hear it.

I gave my own view on this blog at the time David sent his tweet. He was being foolish - whatever Gaza about it is not about him - but also making the serious point that military action of the sort undertaken by Israel can be counterproductive.

Don Foster's decision is a blow to those who comb Twitter and the wider web in the hope of finding something they can claim to be offended by and then demand action.

It is also a blow to those in the Liberal Democrats whose chief activity is calling for other people to be thrown out of the party.

Paddy Ashdown foresees the end of Iraq and rise of Kurdistan

And as the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia disappeared from the map, it became clear he was right.

On the Guardian website (and I assume in tomorrow's paper) Paddy Ashdown suggests that a similar process is now taking place in the Middle East:

What is happening in the Middle East, like it or not, is the wholesale rewriting of the Sykes-Picot borders of 1916, in favour of an Arab world whose shapes will be arbitrated more by religious dividing lines than the old imperial conveniences of 100 years ago.As part of these changes, Paddy foresees the Kurds in northern Iraq (bolstered by Western aid) breaking away to form an independent state.

When I was secretary of York Liberal Students around 1979-80 we had a recruiting leaflet. One of the causes it backed was an independent state for the Kurds.

This policy had been inherited from officers who had since left university, but we kept it on the leaflet - even if none of us could have pointed to where Kurdistan would be on a map.

Whoever wrote that leaflet probably envisaged Kurdistan breaking away from Turkey rather than Iraq, but I thought of it when I read Paddy's article.

Rejected Stephen King Short Story Ideas

- It’s the future and they take your thumbs when you get divorced

- It’s the future and they take your thumbs when you get divorced

- Evil car culture

- A man discovers Fargo was real

- A man discovers where the feminists bury the bodies, is killed

- A man who prefers rap music to Creedence is doomed

- A knitting circle accidentally casts a spell

- Postman gets stuck in yard with angry dog, forever

- An old man finally buys a smartphone. Smartphone psychic, dispensing terrible omens

- A joyriding punk discovers a muscle car made out of muscle

- Jim Morrison only person to show up to Doors fan’s birthday party. Surprise: He’s the grim reaper, fan is dead.

- An old woman speaks in ominous gibberish

- A woman switches coffee brands – terrible consequences

- A cloud of smoke looks like an animal, briefly

- Maine is full of sadists

- A man addicted to nostalgia

- Texas is full of sadists, with trite nicknames

- An old jukebox won’t stop playing Creedence

- A milkman keeps seeing a cow down the road from his house

- A lonely man with a whimsical job falls in love with his phone

- The malt shop seems so innocent… and yet

Read more Rejected Stephen King Short Story Ideas at The Toast.

The crooked ladder: the gangster's guide to upward mobility.

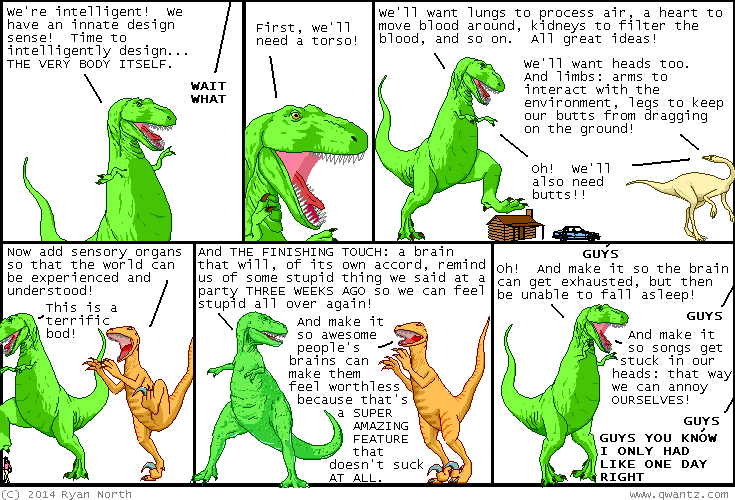

also make it so they can forget the name of people right after they've met them, aweeeesommmmme

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | August 7th, 2014 | next | |

|

August 7th, 2014: Dinosaur Comics has over a decade of comics for you to read! That's a lot of comics, and who wants to go back and read them all in one sitting? YOU? >Perhaps! And that option is available to you. But now there is another option: get a curated selection of Classic Favourites delivered to you every day! Dinosaur Comics is now syndicated on GoComics, and if you go to that site you can get new-to-you comics delivered right too you! ALSO: the comics are at a slightly higher resolution, which may blow your mind. ALSO: you can comment on the comics, which is something I've never had here, but now you can do it there! So it is time to share your opinions. – Ryan | |||

Rogeting

That students could hope to succeed by means of such substitutions suggests that something is broken — in their understanding of how language works, and in their ability to imagine a reader’s response to their writing.

Thanks to Ian Bagger for sending The Guardian article my way.

A related post

Beware of the saurus (Don’t hunt for “better words”)

You’re reading a post from Michael Leddy’s blog Orange Crate Art. Your reader may not display this post as its writer intended.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons 3.0 License.

Unpacking The Fandom Police

Here we go again: about two weeks from now, I will be incessantly bouncing off the walls because of the impending new series of Doctor Who… Actually, I’m doing that already. Oh dear. It’s going to be a long couple of weeks. Anyway, since I started this blog, there’s been a recurring pattern of “exciting Doctor Who thing happens —> I see loads of fandom gatekeeping —> I rant about it on here” and, as I ended up reading Facebook comments this morning, this is no exception. So, let’s get rid of a few elitist myths about fandoms so we can all get back to, you know, enjoying them.

1.) You’re not obliged to toe a party line. Love a series, episode, character, film, scene, album, song… aspect of the fandom that everyone else hates? Or vice versa? Fine. Fandoms don’t have to be hive minds. (We have Daleks for that.) It doesn’t mean you’re not a real fan, or that you’re somehow less intelligent as many fandom elitists like to imply, or that you’re wrong. Basically, you’re allowed to enjoy things, or not.

2a.) You’re entitled to your opinion – and others are entitled to criticise it. Contrary to popular belief, you’re not the only one entitled to an opinion. More generally, this line of thinking is often used to defend bigotry; for example, someone may justify their homophobic view with “free speech, I’m entitled to my opinion”, then when it’s called out dismiss the criticism as an attack because “free speech, I’m entitled to my opinion”. This happens pretty much everywhere, including within fandoms. Also, see point 1, we’re not Daleks, etc. 2b.) Some opinions are more potentially harmful than others. Basically, there’s a difference between “actually, I thought that album was okay” and “actually, I thought that sexist joke was okay”; only one of those may contribute to the perpetuation of an existing oppression.

3a.) You’re allowed to like problematic media. Otherwise, you wouldn’t be allowed to like anything. The “fans vs feminists” divide isn’t real – you can be both! 3b.) You’re allowed to NOT like problematic media. This doesn’t make you humourless, or a spoilsport, or a killjoy, it just means you don’t want to put up with kyriarchy – and, of course, you shouldn’t have to.

4.) You’re allowed to criticise the media you love. To give a personal example, there have been several occasions when I’ve discussed sexism within Doctor Who and/or the fandom on Twitter, only to be met with the response that I’m picking on it. Apparently, I should be focusing on all of media all at once, but anyway: I talk more about Doctor Who because it’s where I actually know what I’m talking about. I talk more about Doctor Who because, well, I bloody love Doctor Who. That’s why I’m bothering to discuss it. That’s why (for instance) sexist tropes and fandom gatekeeping sadden me. If anything, criticising the media you love is a compliment; it means you believe it could be even better.

5.) You’re allowed to be late to the party. If you’re a fan now, you’re not less of one for not being there from the start. Going back to Doctor Who again (sorry…), us under-50s were all late to the party, many new Who fans haven’t seen any classic Who, and (while I’d thoroughly recommend classic Who) that’s okay.

6.) Mainstream isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Older fans of long-running fandoms such as… you can see where this is going, will remember a time when fandom and geekery were shameful and secretive. Nowadays, this isn’t really the case at all. As a younger fan who doesn’t really remember otherwise, I find it really interesting to hear about all that stuff, but sometimes it does inadvertently veer into “these darn kids are getting something for nothing” and, well, surely that’s only a good thing?

7.) (heavy sarcasm in this one) HUGE REVELATION – You’re allowed to be attracted to characters/actors. Yes, even if you’re *GASP* a woman. Furthermore – and this may sound astonishing to some – it is entirely possible to be attracted to characters without it being the central reason you are a fan. And even if that was the reason you got into the fandom in the first place – does it really matter? Shockingly, you don’t actually have to choose between being attracted to people and appreciating what they do, being attracted to characters and also liking other characters, etc, etc. You can still be a fan. Note how it’s only ever female sexuality which is ridiculed as shallow and used to dismiss women within the fandom (no change there, then). And for the record, you’re also allowed to not bother with any of that.

8.) If you like the thing, you can call yourself a real fan. Seriously. That’s all it entails. You don’t have to buy X pieces of merch, or go to X number of events, or know absolutely everything there is to know about it, or have seen/read/listened to/consumed every last bit of related media that exists, or cosplay, or write fanfic, or read it, or anything else. You’re allowed to get things wrong. You’re even allowed to call the Doctor “Doctor Who” or even “Dr Who” – I mean, the original credits did. It doesn’t matter. You just need to like the thing.

9.) You’re allowed to be a casual fan! You’re allowed to just dip into an episode every so often and not care about missing out. You’re even allowed to just wear the T-shirts without knowing all that much about the band. Yes, really. Doing so doesn’t hurt anybody.

10.) Be wary of false panic about other fans. Again, I’ll stick with what I know for this one. I’ve seen so much OUTRAGE about fans thinking Peter Capaldi is too old… but I haven’t actually seen one person say Peter Capaldi is too old. I’ve seen so much fangirls (and it is always girls, see point 11) for apparently referring to Matt Smith as “the third Doctor”… but I haven’t actually seen a single person do that. I’ve seen several posts angry at fans trying to change the fandom name… but I haven’t seen anyone outside those posts actually doing so. There’s a lot of faux-outrage out there.

11.) Question who benefits from this gatekeeping/elitism and how. Even if “fake fans” existed, they wouldn’t be hurting anyone, so why is there all this fuss? Note how quite a bit of this gatekeeping specifically references “girls”, “teenage girls”, “fangirls”, but note also that even when it doesn’t, it’s often coded as being aimed at women (teenage girls in particular) through references to fandoms seen as female-dominated (One Direction being a popular one) and mocked accordingly. Look into the “fake geek girl” trope, and pay attention to double standards.

12.) I’M SORRY, DID SOMEBODY SAY TWELVE

Friendship Is (Still) Countersignaling

Related: Friendship Is Countersignaling

When I was in high school, I was terrified of people asking me to do things with them. Usually they were things I didn’t like, and I’d want to say no, but I’d be worried I was offending them, or that I was looking like this total loser who was never willing to do anything fun.

The situation got much worse if it went on to personal questions, because I might have to reveal I wasn’t as cool as everyone else. Like if I kept refusing invications to do stuff, and someone asked what I did like to do in my spare time, I would have to admit it was a combination of playing Civilization 2, modding Civilization 2, and posting on Civilization 2-related forums. Or if someone asked me who my friends were, I might have to admit I didn’t have very many. I came up with so many clever excuses for avoiding these sorts of conversations, and so many mumbled half-answers that managed to accurately communicate “go away go away go away I can’t think of a non-scary answer right now”.

Meanwhile, now I encounter the same sorts of issues at work and I usually handle it like this:

CO-WORKER: Hey, we’re going to go golfing after work? You want to join us?

ME: Oh, thanks, but I don’t like doing things.

CO-WORKER: Really? Nothing? What do you do in your free time?

ME: Really. Nothing. I sit alone in my room all day quietly.

CO-WORKER: You’ve got to have friends!

ME: Oh, no. I don’t have friends. That sounds waaaay too complicated.

CO-WORKER: But there must be some stuff you like!

ME: Nope! Sorry, I hate everything!

The weird thing is that this has actually made me kind of popular, a combination of people respecting my honesty and assuming that I’m covering up for some kind of super fascinating life I’m not telling them about.

Part of me wishes I could tell 16 year old me about this and save him years of terrified mumbling and phobia of social interactions.

Another part is pretty sure it wouldn’t help. The only reason I’m psychologically able to make this work is that I feel okay about myself socially. I have a lot of people I know and like, I feel like I have developed some decent social skills, and the people at my work know I’m not a total loser because I do good patient care a lot of the time. I feel like if all the evidence (both internal as in my own thoughts, and external as in my friends’ observations) pointed to me actually being a loser, then me giving loser-ish answers to questions would be taken a very different way and would not be socially possible for me.

In other words, I am able to countersignal social skills and being an okay person, but only because I have, through noncountersignally methods, brought myself to a place where me countersignaling was more likely than taking things totally straight.

This reminded me of the oft-maligned dating advice to “just be yourself”.

A lot of people have analyzed this in a lot of different ways, usually not very kindly.

My thought is that being yourself is a form of countersignaling. If you are able to conspicuously not make any effort to impress your date, but still seem like an okay human being – like someone who knows they can afford to not impress their date, rather than someone who’s too unimpressive to impress them even when they’re trying – then being yourself is a pretty good strategy.

On the other hand, using this as actual dating advice for people who are bad at dating is a terrible idea. It would be like me telling 16-year-old-me to use the “I sit in a room all day and do nothing” set of conversational responses. I would be eaten alive.

Depending on how many layers of signaling/countersignaling there are on a given topic, the appropriate advanced-level advice might be suicide for beginners, and vice versa.

Amazon Gets Increasingly Nervous

Amazon is not in the least bit happy about the full-page ad some authors have placed into the New York Times this weekend, complaining about its tactics in its negotiations with Hachette, so it is perhaps not entirely coincidental that this weekend Amazon is trying a new tactic: Trying to convince readers that it is in their best interest to favor Amazon’s business needs and desires.

Thus readersunited.com, which posts a letter from Amazon to eBook readers. Go ahead and take a moment to read it (another version, almost word for word, went out to Kindle Direct authors this morning as well), and then come back.

Back? Okay. Points:

1. First, as an interesting bit of trivia, readersunited.com was registered 18 months ago, which does suggest that Amazon’s been sitting on it for a while, waiting for the right moment to deploy it, which is apparently now.

(Update, 7:03pm — more information on the domain name and when it likely came into Amazon’s possession.)

But as a propaganda move, it’s puzzling. A domain like “ReadersUnited” implies, and would be more effective as, a grassroots reader initiative, or at the very least a subtle astroturf campaign meant to look like a grassroots reader initiative, rather than what it is, i.e., a bald attempt by Amazon to sway readers to its own financial benefit. Amazon isn’t trying to hide its association with the domain — it’s got an Amazon icon right up there in tab — so one wonders why Amazon didn’t just simply post it on its own site, to reinforce its own brand identity. The short answer is likely this: It’s just a really clumsy attempt to reinforce the idea that Amazon is doing this for readers, rather than for its own business purposes.

Well, surprise! It’s not. That much is obvious in the Tab header for readersunited, which (currently, at least) reads: “An Important Kindle request.” That much is correct — Amazon is doing this to support its own Kindle brand, not directly for readers (or for authors) at all. It was (again) clumsy of Amazon to leave that in there, but then I don’t think much of Amazon’s messaging in this corporate battle with Hachette has been particularly good. Amazon’s PR department is good at not commenting on its business practices; when it does comment, it does a lot of flubbing.

2. Amazon reheats in this new letter a number of arguments it made in a previous letter, arguments which have been picked apart by me and others. I’ll refer you to my previous commentary on the matter for further elucidation, and otherwise note that in general Amazon’s points make perfect and logical sense as long as one proceeds from the assumption that Amazon is the only distributor of books whose business needs one should ever consider.

Sadly for Amazon, the real world is not like that. Readers might see a benefit in not having Amazon being the only distributor of books in the world — if, for example, they like having physical bookstores in their home towns, employing local people and contributing to the local economy, and keeping money in the area rather than shipped to Seattle, or if, simply as a matter of practicality, they remember that companies trying to drive the market toward monopoly rarely are on the side of the consumer in the long run. Or for any other number of reasons.

3. Amazon’s new(ish) argument appears to be that the eBook is a new and amazing medium (which is in many ways true), and compares it to the paperback disrupting the publishing industry before World War II. Well, let’s talk about that for a second.

Leaving aside that Amazon’s initial phrasing of their argument seems to be largely and clumsily lifted from a Mental Floss article, and that paperback books existed well before the 1930s — see “penny dreadfuls,” “dime novels” and “pulps” (further comment on these and other flubs here and here) — the central problem with Amazon’s argument is economic, to wit, it’s trying to say that its drive to have all eBooks priced at $9.99 is just like paperbacks being priced ten times cheaper than hardcover books.

Well, except that $9.99 isn’t one tenth of the price of a hardcover book, otherwise hardcover books would regularly cost $100, which admittedly is a bit steep. $9.99 is something like 40% of the cover price of most hardcovers, and since most retailers discount from the cover price of a hardcover, the real-world price differential decreases from there. This is hardly the exponential cost savings that Amazon wishes to embed into the mind of the people to whom it is making its argument.

Amazon also continues the legerdemain of hyping very high e-book price points — it’s doubling down on its previous $14.99 boogeyman price point by introducing another one that’s even higher: $19.99! — while conveniently ignoring the fact that most eBooks are priced at neither of those price points, even ones tied into a new hardcover release.

As an anecdotal piece of information, the eBook price of my upcoming novel Lock In is $10.67 on Amazon — not $14.99 or even $19.99 — a price that is roughly 40% off the price that Amazon is willing to sell you the hardcover for ($18.62). As another anecdotal piece of data, Lock In currently the most expensive English-language eBook of mine in Amazon’s Kindle store — the other prices range from 99 cents (for various short stories of mine) to $9.01.

When Amazon’s absolutely-amazing, totally-disruptive price point of $9.99 is in fact less than 10% off from the real world price point of the latest eBook from a Hugo-winning, New York Times best-selling novelist with two television series in development, and more than the price of every other eBook of his, what does that tell you? It might tell you many things, but the thing I’m hoping it tells you is that the $9.99 price point is less about changing the world than it is about serving Amazon’s own particular business needs — not the needs of the consumer or (for that matter) the author or the larger business of bookselling. It’s worth it for readers to ask what Amazon’s business needs are.

4. My notation that only one of my English language eBooks is priced above $9.99 at all should bring home the point that this battle between Amazon and Hachette isn’t really about consumer choice. The consumer who wishes to buy a John Scalzi eBook will discover that more than 90% of his work available for sale for less than $10, just as she will discover that large majority of work of almost all authors is priced below $10. The budget-minded consumer is spoiled for choice in the sub-$10 eBook realm. If Amazon fails to get Hachette to bring down its prices on its new releases, than consumers will still be spoiled for choice in the sub-$10 eBook realm.

What it’s about is two large corporations — Amazon and Hachette — arguing about whose business needs are more important. Hachette wants to continue to price new-release eBooks above $9.99 so it can continue to make what it considers an acceptable amount of profit on new releases and then lower the price point as the new release matures, capturing other audiences as it goes. Amazon wants to nail the price at $9.99 because it’s in the business of selling everything to everyone, and price control is a fine way of locking the consumer into its business ecosystem.

But Hachette colluded! Leaving aside that Hachette’s past actions are neither here nor there in this new set of negotiations between these two corporations, if Amazon wishes to note the mote of illegal business action in Hachette’s eye, it ought to equally note the beam in its own. Which is to say that Amazon is no angel on the side of consumers any more than Hachette is — they both have their business interests, and by all indications they are both willing to see what they can get away with until they’re called on it.

It makes sense that Amazon wants to make this about the benefit for the consumer (or the author), just like any corporation wants to make their wholly self-interested actions look as if they’re meant to directly benefit their consumers and stakeholders. Consumers, like everyone else, should ask what’s really at stake.

5. Amazon is correct about one thing in this new letter — authors aren’t of a single mind about this. There are a lot of authors who rely primarily on publishers like Hachette for their income; there are a lot of authors who rely primarily on Amazon for their income; there are a lot of authors who publish in a wide range of ways and receive their income from both and from other sources as well. They will all argue from their own economic point of view because that’s how they keep their lights on. This is not (necessarily) disingenuous, but it may be uninformed or heavily biased depending on the knowledge and inclinations of the author in question.

Readers need to be aware of this and factor in who is saying what, and how their bread is buttered. They should also read more than one author on the subject. Corporations — and in this case Amazon and Hachette — benefit the less you know about their reasons for doing anything; their promoters and detractors benefit when you only take their word for things. So don’t. Find out more, and don’t rely on a single source for information on anything. Including me — look, I’m pretty sure I’m reliably skeptical all the way around, here, and anyone who thinks I have have it in for Amazon while fawning over large publishing houses is delightfully misinformed. But then I would think that, wouldn’t I. So, yeah, get other viewpoints. More information is always good.

6. With that said, if I were a writer whose primary source of income was Amazon’s publishing platform, I would be rooting like hell for Hachette to win this particular round of negotiations. Why? Because if I buy into the argument that Hachette, et al are artifically propping up eBook prices for their own benefit, and I’ve priced my own work below those artifically high price points, then in point of fact I’m cleaning up in the heart of the market while Hachette, et al are skimming in the margins — and the very last thing I want is a large and now-hungry corporation now competing with me at my price point out of necessity. Driving Hachette and all the other publishers into my territory is not likely to work out for me very well.

But they can’t compete there! They’ll die! They’re dying already! Well, I know you want to believe that. But if you’re basing your writing life on that assumption, then you’re leaving yourself open to a very very rude surprise. You need to understand that nearly all of these publishers have been around for a very long time — decades and in some cases centuries — and they’ve seen more market shifts in publishing and in the book market than possibly you can imagine, some of which were as disruptive as the current one. How many disrupting mammals have these lumbering dinosaurs already seen come and go? And believe this: These large publishers may or may not be able to eat Amazon, but they can surely eat you.

I think it is a very good thing that self-publishing and electronic publishing has come and shaken things up in the publishing field; it’s wonderful that authors can connect with readers without having to route through a publisher they have to convince that this audience is there. It is correct that large publishers tend to the conservative and safe, and do what they know, and often only what they know; it is correct that many authors are better off doing their own thing without them. It is wonderful, as a writer, to have options. Speaking for myself, I know I am better off because I have the option, at any time, to chuck my publishers and make a go of it myself. It keeps them appreciative of me, at the very least. But it does not follow that Amazon prevailing in this particular negotiation with Hachette signals the end of “traditional publishing” or that any particular author — independent or otherwise — will benefit if it did. It doesn’t follow that Amazon prevailing in this particular negotiation is beneficial to anyone other Amazon.

If Amazon does not prevail in this argument, it changes nothing for the authors who already use it as their primary means of distribution. They are still in the marketplace, they are still (largely) pricing their works below the very highest end of “traditional publishers” and therefore able to take advantage of readers who are motivated by price, and they are still able to benefit from not having to share their income on the work with anyone but Amazon.

If readers are in fact primarily motivated by price, then the revolution is already here and indie publishers and authors and readers are already benefiting from it while the traditional publishers slowly thrash and die of hypoxia. In which case all that Amazon will do by forcing publishers into lower price points is give them a shot of oxygen and cause them to compete on the point where indies presumably have the advantage: Price. If I were an indie author, I would rather let the publishers thrash and die away from me, then thrash near me and possibly crush me in their dying throes — which may not in fact be dying throes at all and just merely crushing me.

In sum and once again: Amazon is not your friend. Neither is any other corporation. It and they do what they do for their own interest and are more than willing to try to make you try believe that what they do for their own benefit is in fact for yours. It’s not. In this particular case, this is not about readers or authors or anyone else but Amazon wanting eBooks capped at $9.99 for its own purposes. It should stop pretending that this is about anything other than that. Readers, authors, and everyone else should stop pretending it’s about anything other than that, too.

(Update, 8/11: Followup responses to criticisms I’ve seen to this and other Amazon/Hachette pieces I’ve written.)

The Fourth

It is the fourth of July. I've woken early, fed the cats and spent an hour or so reading. My wife is still in bed, but is now awake. She has been off work for a few days, the first holiday she has taken in what seems like at least a year. Junior is staying with his father, and so we have had a relaxing time.

'I don't think George Washington has been yet,' I tell her. 'The pumpkin pie and beer we left out are still under the tree.' It's an old joke but it still raises a laugh, and seems to work for both Independence Day and Thanksgiving. If you've been good, George Washington will bring you presents.

'Was this independence from England, or was it something to do with the civil war?' I still have trouble recalling which public holiday relates to which historical occasion. I've been here just three years.

'Independence from England.' Bess then tells me that Canadians once tried to burn down the White House.

'During the war of independence?'

'Yes.'

'What the hell did it have to do with them?'

'They sided with your lot.'

'Really?'

In my head, the thousands of square miles of land north of the 49th parallel transmogrify into a cartoon character, a geographical slab of orange mashed potato with legs and a face.

Ooh ooh, I'll help you, England. I'm on your side. It turns to blow a raspberry at a similarly shaped character representing the United States.

'I'll see you in a couple of hours.' I kiss my wife on the nose, pull on my boots, and head out of the kitchen door. Yesterday I bought a small United States flag in HEB. There were a load of them on sale at the checkout, one dollar each, the Stars & Stripes on a rectangle of cloth attached to a foot or so of wooden dowel. I bought one because I could think of no good reason not to and they seemed quite nicely made, and now I've mounted it on the rear of my bicycle, expecting it will catch the breeze as I cycle along. I know people who may find this ridiculous, but I'm past caring. I also wear a Stetson because I burn easily and it keeps the sun off my head, and a T-shirt which was a present from Bess's aunt which bears the message you might give some serious thought to thanking your lucky stars you're in Texas. It is exactly this sort of confrontational humour which appeals to me.

I saddle up, in a manner of speaking, and freewheel out onto the street, across Harry Wurzbach Parkway, and down past the school. It's only just gone half past seven, and although the air is warm it's still quite pleasant. I'm pleased with myself. I try to cycle fifteen miles every day, so during summer, the earlier I can get going, the better. Most of the trail I follow is through woodland, so I'm in the shade, but the heat nevertheless becomes a little too much to endure if I leave too late in the morning.

The roads are quiet and for some reason I find myself thinking of Brackenridge Park. We used to spend a few hours there every Wednesday evening. Bess's mother would collect Junior from school, and once my wife had finished work, we would all meet up at Brackenridge Park. There is a race held there on Wednesday evenings, and Sid always runs, so we go along to watch him and to lend our support. Sid is an old friend of the family to the point of more or less being one of the family. He is in his seventies and is one of the tallest men I have ever met, so it's always fairly easy to spot him, bobbing along happily at the rear of the crowd, at least a couple of feet taller than everyone else. We all wave, and he waves back.

Thirty or so minutes later he will come to find us at one of the benches where Mexican families hold their barbecues.

'Howdy, Mr. Burton.' He has the smile of someone who knows something but isn't telling, and he speaks slowly, with disconcertingly lengthy pauses occurring mid-sentence. 'Well, you know I've been reading,' - and into one of those pauses as he sits, arranges his long legs beneath the bench, then considers the rest of the sentence before at last submitting 'about your MI5 and your secret service.'

I'm English, so they're my MI5 and my secret service. I can never quite work out why Sid imagines I will have any useful information on these subjects, but I suppose it's his way of bringing some common ground to the conversation. It seems to make him happy, and so that makes me happy. He's Jewish and very, very much a Texan - a cultural mix I could not have envisioned at any point before I came to live here. I suppose we must seem quite exotic to each other in certain respects.

'So how's my silver fox?'

He is now addressing Bess's mother, who probably heard fine but isn't sure how to respond to that one. Bess and I exchange a look of amused incredulity, and even Junior seems to find it funny to hear his grandmother addressed as such.

Silver fox!

My wife's mother might be described as the strong, silent type. She doesn't give much away, and tends to speak only when she has something she feels is worth saying. I am told she once talked a gun-wielding nutcase in a diner into giving himself up, and I can well believe it. She carries herself with the sort of authority which makes the rest of us disinclined to address her in terms quite so playful as silver fox.

Junior has just called Sid bald eagle, too quiet for Sid to hear and offered as a sort of counterpoint to silver fox. My wife is silently trying to swallow back her laughter. Sid, as Junior has clearly noted, has a certain heraldic grandeur, and so the nickname seems well chosen if a little blunt.

We haven't met up at Brackenridge Park in a while, and I wonder why I should be thinking of it right now as I turn off Corinne Drive and head down Eisenhauer Road towards the market on my bicycle. I suppose maybe that it could be the weather, or just that I feel similarly relaxed.

I cycle onto the path that is the Tobin Trail, which follows Salado Creek from the Spanish missions in the south of the city all the way up to McAllister Park in the north. There are quite a few people out this morning, running, cycling, or walking their dogs, which are mostly either chihuahuas or dachshunds for some reason - both popular breeds in San Antonio. A few people have small flags pinned to their cycle helmets or elsewhere. Everyone smiles and says good morning, and now I remember just why I picked out my one dollar Stars & Stripes from the bin next to the checkout at HEB. It's because I like living here.

A few hours later on some social networking site I see that an acquaintance has marked the occasion with a quote from Harold Pinter:

The crimes of the United States have been systematic, constant, vicious, remorseless, but very few people have actually talked about them. You have to hand it to America. It has exercised a quite clinical manipulation of power worldwide while masquerading as a force for universal good. It's a brilliant, even witty, highly successful act of hypnosis.

I respond with thin sarcasm, adding I wish someone had mentioned this before. Under the circumstances, it doesn't seem to warrant any greater effort on my part. Whilst it may well be true, it has no direct bearing on my situation, and nothing is going to piss me off today.

Apple, Carmen Sandiego, and the Rise of Edutainment

If there was any one application that was the favorite amongst early boosters of personal computing, it was education. Indeed, it could sometimes be difficult to find one of those digital utopianists who was willing to prioritize anything else — unsurprisingly, given that so much early PC culture grew out of places like The People’s Computer Company, who made “knowledge is power” their de facto mantra and talked of teaching people about computers and using computers to teach with equal countercultural fervor. Creative Computing, the first monthly magazine dedicated to personal computing, grew out of that idealistic milieu, founded by an educational consultant who filled a big chunk of its pages with plans, schemes, and dreams for computers as tools for democratizing, improving, and just making schooling more fun. A few years later, when Apple started selling the II, they pushed it hard as the learning computer, making deals with the influential likes of the Minnesota Educational Consortium (MECC) of Oregon Trail fame that gave the machine a luster none of its competitors could touch. For much of the adult public, who may have had their first exposure to a PC when they visited a child’s classroom, the Apple II became synonymous with the PC, which was in turn almost synonymous with education in the days before IBM turned it into a business machine. We can still see the effect today: when journalists and advertisers look for an easy story of innovation to which to compare some new gadget, it’s always the Apple II they choose, not the TRS-80 or Commodore PET. And the iconic image of an Apple II in the public’s imagination remains a group of children gathered around it in a classroom.

For all that, though, most of the early educational software really wasn’t so compelling. The works of Edu-Ware, the first publisher to make education their main focus, were fairly typical. Most were created or co-created by Edu-Ware co-founder Sherwin Steffin, who brought with him a professional background of more than twenty years in education and education theory. He carefully outlined his philosophy of computerized instruction, backed as it was by all the latest research into the psychology of learning, in long-winded, somewhat pedantic essays for Softalk and Softline magazines, standard bearers of the burgeoning Apple II community. Steffin’s software may or may not have correctly applied the latest pedagogical research, but it mostly failed at making children want to learn with it. The programs were generally pretty boring exercises in drill and practice, lacking even proper titles. Fractions, Arithmetic Skills, or Compu-Read they said on their boxes, and fractions, arithmetic, or (compu-)reading was what you got, a series of dry drills to work through without a trace of whit, whimsy, or fun.