Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

T Plus 1: Bombing Japan

Playground

A set of children's swings moves slowly back and forth in the humid breeze. Behind them stands a long building, its windows hung with flowers and birds folded from colored paper.

Mounds of dirt are heaped around a dark opening to the east. It appears to be a shelter of some kind.

Several small children are happily chasing dragonflies north of the swing set. Turning south, you see a group of adults (schoolteachers, by the looks of them), wearily digging another shelter like the first.

A little girl races between the swings, hot on the trail of a dragonfly. She trips and sprawls across the sand, laughing with hysterical glee. Then she sees you.

At first, you're sure she's going to scream. Her eyes dart back and forth between you and the teachers; you can see a cry forming on her lips.

Suddenly, the umbrella in your hand catches her eye. You watch her expression soften from fear to curiosity.

>examine girl

The girl is a cute four or five years old.

The girl can't keep her eyes off the umbrella.

You've noticed a faint sound coming from somewhere overhead. The girl turns to stare at the sky.

>girl, hello

The girl blinks uncomprehendingly.

The sound overhead grows louder. There's no mistaking the drone of aircraft.

The girl looks at you expectantly and tries to pull you towards the shelter.

Muttering with exasperation, the teachers drop their spades and begin to trudge in the direction of the shelter.

One teacher, a young woman, sees you standing in the sandpile and shrieks something in Japanese. Her companions quickly surround you, shouting accusations and sneering at your vacation shorts. You respond by pointing desperately at the sky, shouting "Bomb! Big boom!" and struggling to escape into the shelter.

This awkward scene is cut short by a searing flash.

On August 6, 1945, a B-29 Superfortress piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets dropped the second atomic bomb ever to be exploded in the history of the world — and the first to be exploded in anger — on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later another B-29, piloted this time by Major Charles Sweeney, dropped another — the second and, so far, the last ever to be exploded in anger — on Nagasaki; it’s this event that Trinity portrays in the excerpt above. On August 15, Japan broadcast its acceptance of Allied surrender terms.

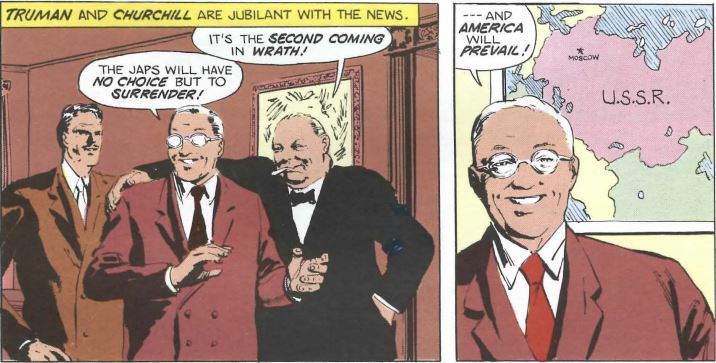

The cultural debate that followed, condensed into four vignettes:

In the immediate aftermath of the event, the support of the American public for the bombings that have, according to conventional wisdom, ended the most terrible war in human history is so universal that almost no one bothers to even ask them about it. One of the few polls on the issue, taken by Gallup on August 26, finds that 85 percent support the decision versus just 10 percent opposed. Some weeks later another poll finds that 53.5 percent “unequivocally” support the country’s handling of its atomic arsenal during the war. Lest you think that that number represents a major drop-off, know that 22.7 percent of the total don’t equivocate for the reason you probably think: they feel that the United States should have found some way to drop “many more” atomic bombs on Japan between August 6 and August 15, just out of sheer bloody-mindedness. Newspapers and magazines are filled with fawning profiles of the “heroes” who flew the missions, especially of their de facto spokesman Tibbets, who comes complete with a wonderfully photogenic all-American family straight out of Norman Rockwell. He named his B-29 the Enola Gay after his mother, for God’s sake! Could it get any more perfect? Tibbets and the rest of the Enola Gay‘s crew march as conquering heroes through Manhattan as part of the Army Day Parade on April 6, 1946. The Enola Gay becomes a hero in her own right, with the New York Times publishing an extended “Portrait of a B-29″ to tell her story. When she’s assigned along with Tibbets himself to travel to Bikini Atoll to possibly drop the first Operations Crossroads bomb, the press treat it like Batman and his trusty Batmobile going back into action. (The Enola Gay is ultimately not used for the drop. Likewise, Tibbets supervises preparations, but doesn’t fly the actual mission.)

Fast-forward twenty years, to 1965. The American public still overwhelmingly supports the use of the atomic bomb, while the historians regard it as has having saved far more lives than it destroyed in ending the war when it did and obviating the need for an invasion of Japan. But now a young, Marxist-leaning economic historian named Gar Alperovitz reopens the issue in his first book: Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam. It argues that the atomic bomb wasn’t necessary to end World War II, and, indeed, that President Truman and his advisers knew this perfectly well. It was used, Alperovitz claims, to send a message to the Soviet Union about this fearsome new power now in the United States’s possession. The book, so much in keeping with the “question everything your parents told you” ethos of the burgeoning counterculture, becomes surprisingly popular amongst the youth, and at last opens up the question to serious historiographical debate in the universities.

Fast-forward thirty years, to the mid-1990s. The Smithsonian makes plans to unveil the newly restored Enola Gay, which has spent decades languishing in storage, as the centerpiece of a new exhibit: The Crossroads: The End of World II, the Atomic Bomb, and the Cold War. The exhibit, by most scholarly accounts a quite rigorously balanced take on its subject matter that strains to address thoughtfully both supporters and condemners of the atomic bombings, is met with a firestorm of controversy in conservative circles for giving a voice to critics of the bombing at all, as well as for allegedly paying too much attention to the suffering of the actual victims of the bombs. They object particularly to the charred relics from Hiroshima that are to be displayed under the shadow of the Enola Gay, and to the quotations from true-blue American heroes like Dwight Eisenhower voicing reservations about the use of the bomb. Newt Gingrich, the newly minted Republican Speaker of the House, condemns the Smithsonian and its director, Martin Harwit, as “cultural elites” telling Americans “they ought to be ashamed of their country.” Tibbets, still greeted as a hero in some circles but now condemned as an out-and-out war criminal in others, proclaims the proposed exhibit simply “a damn big insult” whilst reiterating that he feels not the slightest pang of conscience over what he did and sleeps just fine every night. In the end the grander ambitions for the exhibit are scuttled and Harwit harried right out of his job. Instead the Smithsonian sets up the Enola Gay as just another neat old airplane in its huge collection, accompanied by only the most perfunctory of historical context in the form of an atomic-bombing-justifying placard or two.

Fast-forward another ten years. On November 1, 2007, Paul Tibbets dies at the age of 92. The blizzard of remembrances and obituaries that follow almost all feel compelled to take an implicit or explicit editorial position on the atomic bombings, which are as controversial now as they’ve ever been. Conservative writers lay on the “American hero” rhetoric heavily. It’s the liberal ideologues, though, who become most disingenuously strident this time. Many resort to rather precious forms of psychoanalysis in trying to explain Tibbets’s lifelong refusal to express remorse for dropping the bomb, claiming that it means he had either been a sociopath or deeply troubled inside and holding himself together only through denial. They project, in other words, their own feelings toward the attack onto him whilst refusing him the basic human respect of accepting that maybe the position he had steadfastly maintained for sixty years was an honest, considered one rather than a product of psychosis.

If support for the atomic bombings of Japan equals mental illness there were an awful lot of lunatics loose in the bombings’ immediate aftermath. If we could go back and ask these lunatics, they’d likely be very surprised that people are still debating this issue at all today. Well before 1950 the history seemed largely to have been written, the debate already long settled in the form of the neat logical formulation destined to appear in high-school history texts for many decades, destined to be trotted out yet again for the bowdlerized version of the Enola Gay exhibit. Japan, despite being quite obviously and comprehensively beaten by that summer of 1945, still refused to surrender. But then, as the Smithsonian’s watered-down exhibit put it: “The use of the bomb led to the immediate surrender of Japan and made unnecessary the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands. Such an invasion, especially if undertaken for both main islands, would have led to very heavy casualties among American, Allied, and Japanese armed forces, and Japanese civilians.” The bombings were terrible, but much less terrible than the alternative of an invasion of the Japanese home islands, which was estimated to likely cost as many as 1 million American casualties, and likely many times that Japanese.

For a sense of the sheer enormity of that figure of 1 million casualties, consider that it’s very similar to the total of American casualties in both Europe and the Pacific up to the summer of 1945. Thus we’re talking here about a potential doubling of the the United States’s total casualties in World War II, and very possibly the same for Japan’s already much more horrific toll. The only other possible non-nuclear alternative would have been a blockade of the Japanese home islands to try to starve them out of the war, a process that could have taken many months or even years and brought with it horrific civilian death and suffering in Japan itself as well as a slow but steady dribble of Allied casualties amongst the soldiers, sailors, and airmen maintaining the blockade. For a nation that just wanted to be done with the war already, this was no alternative at all.

Against the casualties projected for an invasion or even an extended blockade, the 200,000 or so killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki starts to almost seem minor. I’d be tempted to say that you can’t do this kind of math with human lives, except that we did and do it all the time; see the platitudes about the moderate, unfortunate, but ultimately acceptable “collateral damage” that has accompanied so many modern military adventures. So, assuming we can accept that, while every human life is infinitely precious, some infinities are apparently bigger than others (Georg Cantor would be proud!), the decision made by Truman and his advisers would seem, given the terrible logic of war, the only reasonable one to make… if only this whole version of the administration’s debate wasn’t a fabrication.

No, in truth Truman never had anything like the debate described above with his staffers — unsurprisingly, as the alleged facts on which it builds are either outright false or, at best, highly questionable. Far from being stubbornly determined to battle on to the death, Japan was sending clear feelers through various diplomatic channels that it was eager to discuss peace terms, with the one real stumbling block being the uncertain status under the Allies’ stated terms of “unconditional surrender” of the Emperor Hirohito. Any reasonably perceptive and informed American diplomat could have come to the conclusion that was in fact pretty much the case in reality: that many elements of this proud nation were still in the Denial phase of grief, clinging to desperate pipe dreams like a rescue by, of all people, a Soviet Union that suddenly joined Japan against the West — but, as those dreams were shattered one by one, Japan as a whole was slowly working its way toward Acceptance of its situation. Given these signs of wavering resolution, it seems highly unlikely that an invasion of Japan, should it have been necessary at all, would have racked up 1 million casualties on the Allied side alone. That neat round figure is literally pulled out of the air, from a despairing aside made by Truman’s aging, war-weary Secretary of War Henry Stimson. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall engaged in a similar bit of dead reckoning, based on nothing but intuition, and came up with a figure of 500,000. Others reckoned more in the range of 250,000. The only remotely careful study, the only one based on statistical methods rather than gut feelings, was one conducted by the Army that estimated casualties of 132,500 — 25,000 of them fatalities — for an invasion of Kyushu, 87,500 casualties — 21,000 of them fatalities — if a follow-up invasion of Honshu also became necessary. Of course, nobody really knew. How could they? The only thing we do know is that 1 million was the highest of all the back-of-the-napkin estimations and over four times the military’s own best guess, meaning it’s better taken as an extreme outlier — or at least a worst-case scenario — than a baseline assumption.

The wellspring for the problematic traditional narrative about the use of the atomic bomb is an article which Henry Stimson wrote for the February 1947 issue of Harper’s Magazine. This article was itself written in response to the first mild stirrings of moral qualms that had begun the previous year in the media in response to the publication of John Hersey’s searing work of novelistic journalism Hiroshima. Stimson’s response sums up the entire debate and the ultimate decision to drop the bombs so eloquently, simply, and judiciously that it effectively ended the debate when it had barely begun. The two most salient planks of what’s become the traditionalist view of the bombing — Japan’s absolute refusal to surrender and that lovely, memorable round number of 1 million casualties — stand front and center. This neat version of events would later be enshrined in the memoirs of Truman and his associates.

Yet, as we’ve seen, Stimson’s version of the debate must be, at best, not quite the whole truth. I want to return to it momentarily to examine the biggest lie therein, which I consider to be profoundly important to really understanding the use of the bomb. But first, what of the stories told by those of later generations who would condemn the use of the bomb? They’ve staked various positions over the years, ranging from unsubstantiated claims of racism as the primary motivator to arguments derived from moral absolutism: “One cannot firmly be against any use of nuclear weapons yet make an exception in the case of Hiroshima,” writes longtime anti-nuclear journalist and advocate Greg Mitchell. Personally, I don’t find unnuanced tautologies of that stripe particularly helpful in any situation; there’s always context, always exceptions.

By far the strongest argument made against the use of the atomic bomb is the one that was first deployed by Gar Alperovitz to restart the debate in 1965: that external political concerns, particularly the desire to send a message to the Soviet Union, had as much or more to do with the use of the bomb than a simple desire to end the war as quickly and painlessly as possible. While the evidence isn’t quite as cut-and-dried as many condemners would have it, there’s nevertheless enough fire under this particular smokescreen to make any proponent of the atomic bombing as having merely been doing what was necessary to end the war with Japan at least a bit uncomfortable.

It was the evening of the first day of the Potsdam Conference involving Truman, Stalin, Winston Churchill, and their respective staffs when Truman first got word of the success of the Trinity test. Many attendees remarked the immediate change in his demeanor. After having appeared a bit hesitant and unsure of himself during the first day, he started to assert himself boldly, almost aggressively, against Stalin. Suddenly, noted a perplexed Churchill, “he told the Russians just where they got on and off and generally bossed the whole meeting.” Only when Churchill got word from his own people of the successful test did all become clear: “Now I know what happened to Truman yesterday…”

There follow Potsdam in the records of the administration’s internal discussions a disturbing number of expressions of hopes that the planned atomic bombings of Japan will serve as a forceful demonstration to Stalin that the United States should not be trifled with in the fast-approaching postwar world order. Secretary of State Jimmy Byrnes in particular gloated repeatedly that the atomic bomb should make the Soviets “more manageable” in general; that it would “induce them to yield and agree to our positions”; that it had given the United States “great power.”

But we have to be careful here in constructing a chain of causality. While it’s certainly clear that Truman and many around him regarded the bomb as a very useful lever indeed against increasing Soviet intractability, this was always discussed as simply a side benefit, not a compelling reason to use the bomb in itself. There were, in other words, lots of musing asides, but no imperatives in the form of “drop the bomb so that we can scare the Russians.” Truman’s diary entry after learning of the Trinity test mentions the Soviets only as potential allies against Japan: “Believe Japs will fold up before Russia comes in. I am sure they will when Manhattan explodes over their homeland.”

If we consider actions in addition to words the situation begins to look yet more ambiguous. Prior to Potsdam the United States had been pushing the Soviet Union with some urgency to enter the war against Japan, believing a Soviet invasion of Manchuria would tie down Japanese troops and resources should an American-led home-island invasion become necessary. The Truman administration also believed a Soviet declaration might, just might, provide the final shock that would bring Japan to its senses and cause it to surrender without an invasion. But in the wake of Trinity American diplomats abruptly ceased to pressure their Soviet counterparts. The Soviet Union would declare war at last anyway on August 8 (in between the two atomic bombings), but the United States, once it had the bomb, would seem to have judged that ending the war with the bomb would be preferable for its interests than having the war end thanks to the Soviet Union’s entry. The latter could very well give Stalin postwar justification for laying claim to Manchuria or other Japanese territories, claiming part of the spoils of a war in which the Soviet Union had participated only at the last instant. An additional implicit consideration may have been the conviction of Byrnes and others that it wouldn’t hurt postwar negotiations a bit to show Stalin just what a single American bomber could now do. The realpolitik here isn’t pretty — it seldom is — but what to make of the whole picture is far from clear. The words and actions of Truman and his advisers would seem ambiguous enough to be deployed in the service of any number of interpretations, from condemnations of them as war criminals to assertions that they were simply doing their duty in prosecuting to the relentless utmost of their abilities their war against an implacable enemy. Yes, interpretations abound, most using the confusing facts as the merest of scaffolds for arguments having more to do with ideology and emotion. I won’t presume to tell you what you should think. I would just caution you to tread carefully and not to judge too hastily.

In that spirit, it’s time now to come back to the biggest lie in Stimson’s article. Quite simply, the entire premise of the article is untrue. Actually, there was no debate at all over whether the atomic bomb should be used on Japan.

Really. Nowhere is there any record of any internal debate at all over whether the atomic bomb should be dropped on Japan. There were debates over when it should be used; on which cities it should be used; whether the Japanese should be warned beforehand; whether it should be demonstrated to the Japanese in open country or open ocean before starting to bomb their cities. But no one, no one inside the administration ever even raised the shadow of a suggestion that it should simply be declared too horrible for use and mothballed. Not even among the scientists who built the bomb, many of whom would become advocates in the postwar years for atomic moderation or abolition, is there even a hint of such an idea. Even Niels Bohr, who was frantically begging anyone in Washington who would listen to think about what the bomb might mean to the future of civilization, simply assumed that it would be used as soon as it was ready to end this war; his concern was for the world and the wars that would follow. Interestingly, the only on-the-record questioners of the very idea of using the atomic bomb are a handful from the military who had no direct vote on the strategic conduct of the war in the Pacific, like — even more interestingly — Dwight Eisenhower. Those unnoticed voices aside, the whole debate over the use of the atomic bomb on Japan is largely anachronistic in that nobody making the big decisions at the time ever even thought to raise it as a question. The use of the bomb, now that it was here, was a fait accompli. I really believe that this is a profoundly important idea to grasp. If you insist on seeing this conspicuously missing debate as proof of the moral degradation of the Truman administration, fair enough, have at it. But I see it a little bit differently. I see it as a sign of the difference between peace and war.

The United States has visited war upon quite a number of nations in recent decades, but the vast majority of Americans have never known war — real war, total war, war as existential struggle — and the mentality it produces. I believe that this weirdly asymmetrical relationship with the subject has warped the way many Americans view war. We insist on trying to make war, the dirtiest business there is, into a sanitized, acceptable thing with our “targeted strikes” and our rhetoric about “liberating” rather than conquering, all whilst wringing our hands appropriately when we learn of “collateral damage” among civilians. Meanwhile we are shocked at the brutal lengths the populations of the countries we invade will go to to defend their homelands, see these lengths as proof of the American moral high ground (an Abu Grahib here or there aside), while failing to understand that what is to us a far-off exercise in communist control or terrorist prevention is to them a struggle for national and cultural survival. Of course they’re willing to fight dirty, willing to do just about anything to kill us and get us out of their countries.

World War II, however, had no room for weasel words like “collateral damage.” It was that very existential struggle that the United States has thankfully not had to face since. This brought with it an honesty about what war actually is that always seems to be lacking in peacetime. If the conduct of the United States during the war in the Pacific was not quite as horrendous as that of Japan, plenty of things were nevertheless done that our modern eyes would view as atrocities. Throughout the war, American pilots routinely machine-gunned Japanese pilots who had bailed out of their stricken aircraft — trained pilots being far, far more precious a commodity to the Japanese than the planes they flew. And on the night of March 9, 1945, American B-29s loosed an incendiary barrage on Tokyo’s residential areas carefully planned to burn as much of the city as possible to the ground and to kill as many civilians as possible in the process; it managed to kill at least 100,000, considerably more than were killed in the atomic bombing of Nagasaki and not far off the pace of Hiroshima. These scenes aren’t what we think of when we think of the Greatest Generation; we prefer a nostalgic Glen Miller soundtrack and lots of artfully billowing flags. Our conception of a World War II hero doesn’t usually allow for the machine-gunning of helpless men or the fire-bombing of civilians. But these things, and much more, were done.

World War II was the last honest war the United States has fought because it was the last to acknowledge, at least tacitly, the reality of what war is: state-sponsored killing. If you’re unlucky enough to lead a nation during wartime, your objective must be to prosecute that war with every means at your disposal, to kill more of your enemy every single day than he kills of your own people. Do this long enough and eventually he will give up. If you have an awesome new weapon to deploy in that task, one which your enemy doesn’t possess and thus cannot use to retaliate in kind, you don’t think twice. You use it. The atomic bomb, the most terrible weapon the world has ever known, was forged in the crucible of the most terrible war the world has ever known. Of course it got used. The atomic bombings of Japan and all of the other terrible deeds committed by American forces in both Europe and the Pacific are not an indictment of Truman or his predecessor Roosevelt or of the United States; they’re an indictment of war. Some wars, like World War II, are sadly necessary to fight. But why on earth would anyone who knows what war really means actually choose to begin one? The collective American denial of the reality of war has enabled a series of elective wars that have turned into ugly, bleeding sores with no clear winners or losers; somehow the United States is able to keep mustering the will to blunder into these things but unable to muster the will to do the ugly things necessary to actually win them.

The only antidote for the brand of insanity that leads us to freely choose war when any other option is on the table is to be forced to stop thinking about it in the abstract, to be confronted with some inkling of the souls we’re about to snuff out and the suffering we’re about to cause. This is one of the services that Trinity does for us. For me, the most moving moment in the entire game is the one sketched out at the beginning of this article, when you meet a sweet little girl who’s about to become a victim of the world’s second atomic-bomb attack. Later — or earlier; chronology is a tricky thing in Trinity — you’ll meet her again, as an old woman, in the Kensington Gardens.

>examine woman

Her face is wrong.

You look a little closer and shudder to yourself. The entire left side of her head is scarred with deep red lesions, twisting her oriental features into a hideous mask. She must have been in an accident or something.

A strong gust of wind snatches the umbrella out of the old woman's hands and sweeps it into the branches of the tree.

The woman circles the tree a few times, gazing helplessly upward. That umbrella obviously means a lot to her, for a wistful tear is running down her cheek. But nobody except you seems to notice her loss.

After a few moments, the old woman dries her eyes, gives the tree a vicious little kick and shuffles away down the Lancaster Walk.

That scene breaks my heart every time I read it, and I’m still not entirely sure why.

I like the fact that Trinity goes to Nagasaki rather than Hiroshima. The Hiroshima attack, the more destructive of the two bombings in human lives by a factor of at least two and of course the first, normally gets all of the attention in art and journalism alike. Indeed, it can seem almost impossible to avoid emphasizing Hiroshima over Nagasaki; I’ve done it repeatedly in this article, even though I started out vowing not to. “We are an asterisk,” says Nagasaki sociologist Shinji Takahashi with a certain bitter sense of irony. “The inferior a-bomb city.” Nagasaki wasn’t even done the honor of being selected as a target for an atomic bomb. The B-29 that bombed Nagasaki had been destined for Kokura, but settled on Nagasaki after cloud cover and drifting smoke from a conventional-bombing raid made a drop on Kokura too problematic. An accident of clouds and wind cost 50,000 or more citizens of Nagasaki their lives, and saved the lives of God only knows how many in Kokura. As the Japanese themselves would say, such is karma. And such is the stuff of tragedy.

Problem Book in Relativity and Gravitation: Free Online!

If I were ever to publish a second edition of Spacetime and Geometry — unlikely, but check back in another ten years — one thing I would like to do would be to increase the number of problems at the end of each chapter. I like the problems that are there, but they certainly could be greater in number. And there is no solutions manual, to the chagrin of numerous professors over the last decade.

What I usually do, when people ask for solutions and/or more problems, is suggest that they dig up a copy of the Problem Book in Relativity and Gravitation by Lightman, Press, Price, and Teukolsky. It’s a wonderful resource, with twenty chapters chock-full of problems, all with complete solutions in the back. A great thing to have for self-study. The book is a bit venerable, dating from 1975, and the typesetting isn’t the most modern; but the basics of GR haven’t changed in that time, and the notation and level are a perfect fit for my book.

And now everyone can have it for free! Where by “now” I mean “for the last five years,” although somehow I never heard of this. Princeton University Press, the publisher, gave permission to put the book online, for which students everywhere should be grateful.

If you’re learning (or teaching) general relativity, you owe yourself to check it out.

Hoist by their own petard

The SNP have indeed been claiming this and this has almost certainly added impetus to their recent surge leaving Labour (if the polls are to be believed) at risk of losing a majority of their Scottish held seats.

It is ridiculous that Labour would be considered to be exactly the same as the Tories just because they happened to be on the same side in a particular campaign. It's the sort of stupidly simplistic argument that we see far too often in politics.

But I am afraid my response to Labour on this is "Ah Diddums".

Because "Labour are exactly the same as the Tories" in Scotland is pretty much identical to "The Lib Dems are exactly the same as the Tories" in the whole of the UK, a line Labour has been pushing since 11th May 2010. A claim which is equally as ridiculous that just because a party is in coalition with another party that means they are now exactly the same party.

I for one am delighted to see Labour being hoist by their own petard in this way.

The Phantom Menaced

It’s hard to know what to think of things like this. There’s something to be said, I suppose, for being reminded that Seattle, where I live, is indeed a liberal bubble, its progressive policies and forward-thinking politics an aberration even in the left-leaning Pacific Northwest, and that much of the rest of Washington state is populated by militiamen, tea party types, and other self-identified American patriots. And I do like to keep up to date on what armed hysteria the gun right is whipping itself into, so I can plan my day accordingly; like the people involved in the protest, I am an owner of multiple firearms, but unlike them, I am not a brain-damaged paranoiac, so it’s useful to be informed about what lunatic degree of terror a perfectly harmless piece of legislation has instilled in these dolts.

The specifics of the ‘protest’ certainly provide lots of opportunity for amusement. The ever-present huckster element manifests itself in the sale of “FIGHT TYRANNY — SHOOT BACK” gimme caps, reputedly to raise bail money; alas for the poor hat-hawker, no arrests were made, and he was forced to keep all that money for himself. The way the hapless crowds were thwarted from their eager act of well-armed civil disobedience by the authorities merely locking the doors is a fine illustration of why the right has never really gotten the whole idea of protest and prefers a nice comforting dose of authoritarianism. And the images of these brave freedom fighters wandering aimlessly through the halls of power trying to find someone who wants to listen to them, huddling in the porticos to avoid getting rained on, and hunkering down outside the governor’s mansion praying to Jehovah to smite someone already are highly comical.

Perhaps the biggest laugh/gasp combination comes from this quote from aging Tumwater sad sack Dave Grenier: “What’s the world coming to when there are people who want to break the law and they won’t let you do it?” Mr. Grenier is present at a protest, ostensibly of the government he believes has lately turned tyrannical, and he seems not to have a clue as to how the government works. One shudders to think of what his conception of law enforcement must be, as he does not seem to understand that its very foundation is not letting people break the law when they want to. (A supplemental giggle can be had from Monroe-based elected official Elizabeth Scott, who, after a show-us-your-tits display of top-grade pandering wherein she flashed her pistol to the hooting crowd, claimed “I carry at least one gun every day because a cop is too heavy and a guard is too heavy.” Rep. Scott might wish to visit Seattle more often, as we employ police and security officers capable of moving under their own power, who need not be carried around.)

But the real tell here, the one that has had me in a spin since at least the days of the Clinton administration when the right seemed to make a tectonic shift from merely oppositional to downright eliminationist, came from her colleague in the Washington state house, Rep. Matt Shea of Spokane Valley. Shea is another Tea Party blatherer, and notorious at the state house for his deranged violent outbursts; aside from his loopy political ideas, which include fanatical gay-bashing, he pulled an illegal and unlicensed gun during a traffic incident, has a track record of public and domestic outbursts of anger against fellow elected officials and his Russian bride, and, during his tour in Iraq with the Army National Guard, he was disarmed and referred for psychiatric counseling by his commanding officer for reckless behavior. In other words, just the sort of fellow you want wandering around the capitol building with a loaded gun.

According to reports, Shea “gave a fiery speech that included a list of more than 20 grievances against the government, including militarization of police, high taxes, surveillance programs, Sharia law, and restrictions on guns”. One could quibble on specifics here; it’s odd that someone so virulently opposed to gay marriage would not find Sharia law so objectionable, and it’s very odd to hear a private citizen armed with an assault rifle complain about the militarization of the police. But the real puzzler is that this isn’t a politician focused on an issue; it’s a politician, as so many on the right have become, blowing a scattershot load, shotgun-style, of exaggerations, lies, mischaracterizations, ignorance, and outright fantasy all over his electorate and hoping something sticks.

For all of their flaws, the Democrats, from the ever-shrinking labor left to the mainstreamed big-business technocrats who have held office since the 1980s, at least try to focus on actual issues — problems that really exist, and about which something at least theoretically can be done. Unemployment, income disparity, low wages, corporate corruption, monopoly power, workplace safety, pollution, alternative energy research, science funding, educational reform, police brutality, financial regulation — whatever one’s position on these issues, they are real. They can be observed and measured; their effects can be gauged, their existence can be seen, and the efficacy of attempts to steer them in one direction or another can be at least loosely graded on a variety of criteria.

But not only do so many of today’s Republicans deny the reality of the observable and indisputable issues, preferring a hands-off approach to virtually every economic problem, pretending vaccination is a matter of personal choice and not public health, and flat-out denying the existence of things like climate change; they also replace them with issues that are pure invention. Taxes are still low at the federal level, both in comparison to other highly developed countries and in comparison to our own history — and Washington doesn’t have a state tax. Sharia law is a pure fantasy in America, as much based in political reality as dragons or moon-men — and in Washington, we’re demographically more likely to be forced to swear fealty to the emperor of Japan than we are to become subject to Sharia law. Despite the seeming daily occurrence of gun murders and mass shootings, not a single piece of meaningful gun control legislation has been passed by the federal government in decades — and the one passed here in Washington was exceptionally mild and had widespread popular support.

The whole foundation of the Tea Party movement was that the American government had become so alienated from the ideals and goals of its people, that it had so abrogated the Constitution, that it represented an excrescence on the nation that needed to be expunged, no differently than our initial overthrow of the British. But despite its long life, not a single one of its dire predictions have come true — not a single one. Where is the Islamization of America we were assured was imminent from the Kenyan usurper Barack Hussein Obama? Where are the roving gangs of inner-city thugs, transformed by federal fiat into an army of goons to enforce his dictatorial proclamations? Where, indeed, are those dictatorial proclamations? Where are the padlocked cattle-cars transporting patriotic dissenters to FEMA concentration camps? Where are the blue-helmeted U.N. battalions, forcing socialist wealth distribution down our throats at gunpoint? Where is even a single one of the doomsday prophecies uttered daily by these rubes and hustlers? Obama has less than a year left in office. Even his signature program of health care reform doesn’t clear the bar of being unconstitutional; hell, he didn’t even manage to get insurance companies out of the equation, let alone come up with death panels or abortion on demand or strip-mall Mengeles or whatever other science-fiction nonsense these two-bit cretins have been fulminating about for the last seven years.

Why people continue to buy into the ramblings of a political party whose program consists of outtakes from The Turner Diaries is the subject for another column. But when people ask me why I am so hard on my fellow Democrats — why I save my strongest criticisms for liberals — this is why. The political struggle is being presented as a battle between bad Democrats and worse Republicans, with my vote, I am assured, either committed to the former or given, by default, to the latter. But to my ears, the Republicans literally have no argument to counter. They are trafficking in pure illusion, describing the political stakes in Fairyland; they have nothing to offer me that is worth arguing against. The battle should be between better or worse solutions to real problems, not between actuality and delusion. I’ll continue to focus on the problems of labor and the left; as far as the right goes, wake me when they talk about something real.

The Good God Project

It isn’t easy, being a god.

This website was founded on the principle that we, as gods, are facing a world where being an omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent deity is a very different thing than it used to be. In a time where civil rights, social justice, feminism, and diversity rule the day, we shouldn’t simply enforce our wills by altering the very fabric of reality the way we did back in olden times (even though we could, if we wanted to). Let’s face it — we’re always going to be gods. And we always want to be good, especially if we get to define what that word means. But are we always going to be good gods? And who even decides that? Answering those questions is what this website is all about, and also ad revenue.

If you’re lucky enough to be a god (although we think gods make their own luck, especially gods of luck), then you’ve probably asked yourself questions like these plenty of times in the past. What should I accept as burnt offerings if my girlfriend is vegan? Why do my worshipers demand omnipresence from me when they know I can’t be everywhere at once? Does embracing polytheism mean I have to hang around those weird-smelling ladies who are super into midwifery? What’s a good way to make subjugation of women sound cool and hip? If I get to order the killing of cartoonists, can I start with the guy who does Momma? We know that, omniscient or not, you need the answers to these questions, without ever questioning your essential nature as lord and master of all creation.

That’s why we started the Good God project. We looked around the internet and saw too many Lokis and not enough Thors. We wanted there to be a place for truly decent gods to discuss their thoughts, their ideas, and yes, their feelings. We knew that you wanted to do more than fulfill the traditional “deity” roles of unleashing plagues, monitoring the fall of sparrows, and issuing post-mortem eternal judgments; you wanted someplace to talk about the things gods aren’t supposed to talk about. Why you’ve never quite been able to carry off a beard, and what you should do about it. How you can never keep track of all the rules about genital malformation. Whose name you’re supposed to call out during sex. Where to find really good craft cocktails on Mount Olympus. When it’s appropriate to discuss that one recurring fantasy you have about running into Amaterasu at a spa weekend without making it seem like you have some kind of Asian fetish.

The Good God project will bring you the best from our editorial staff, consisting of two Olympian gods, three Norse gods, an ancient Babylonian deity, two former staffers for the Huffington Post, and Devang, who works for our angel investor. We’ll also be taking reader submissions (please, no cuneiform) to get the best of what you’re thinking when you aren’t running the engine of the world or righteously smiting the men who lay with other men without even sharing their best grooming tips. We’ll have an entire section on sports tailored specifically for you, a being of such vast and unimaginable power that all human life is but a passing vapor in the air. And, of course, TV recaps.

In our first issue alone, we brought you Opochtli’s essay on bass fishing on Lake Baccarac, Hermes on drone warfare and how it should impact your selection of smartphone apps, Gulki — the Wendic god of cross-dressing — on cross-dressing in ancient Polabia, Will Lietch on the Cardinals’ chances of signing Jesus Christ for the 2016 season, and Zeus on how it’s not really rape if you transform yourself into a songbird or a beam of light first. We also brought in Krishna to live-blog the Grammys, and to explain how it’s impossible for him to be racist because his skin is blue and that’s why it’s okay he used that word to describe Kanye West so many times. And we’re partnering up with some of the finest sites on the web to bring you such award-wanting numericles as “16 Divine Powers You Didn’t Know You Had That Can Get You Laid” and a viral video of a little baby trying on a mitre pretiosa and accidentally breaking its neck. All this for the low price of less than thirteen Philistine foreskins a month!

The Good God Project. Because you don’t have to be a good man to be a great god.

The Sons of Dear Old Clemson

Race relations seem to be at the forefront of the current plan to drag America kicking and screaming back to the mid-19th century, so this sort of thing is fascinating to me. Clemson’s black students have long complained that the university underfunds their programs, fails to hear their grievances, doesn’t give them a voice on campus, and brushes off incidents of racial provocation; the whole thing culminated in this sorry display from one of the university’s upstanding (white) fraternities. Such is the climate that led to the recent push to change the name of Clemson’s main building, which, of course, the college administration declined to do, offering up the familiar explanation that sure, Ben Tillman might have been a questionable guy by today’s oh-so-sensitive standards, but he did a lot for the school, and he’s part of our history, and, hey, what are you gonna do?

Since people in power and the press that thinks its job is to toady people in power as much as possible don’t feel it is particularly important to tell the truth, a bit of a history lesson might be in order here. The post-Civil War state of South Carolina found itself, much to the dismay of well-off landowners and the white supremacist elite, in a nightmare of its own making: thanks to their own massive enslavement of blacks, the voting majority, once those slaves became freedmen, consisted of former slaves who were highly unlikely to vote in the interests of their former masters. Realizing that representative democracy (that is to say, the most sacred principle on which America was founded) was about to bite them in the ass, they decided the best thing to do would be to stop democracy dead in its tracks, in a very literal sense. At first, the legislature tried to ban blacks from voting altogether, and instituted flagrantly unconstitutional laws to deprive them of political influence. When that didn’t work, under the guise of ‘rifle clubs’, the white elite formed racist militias — by every definition of the term, murderous terrorist organizations — and intimidated, assaulted, and killed any blacks foolish enough to believe the North’s victory in the war would mean any improvement in their station.

Into this swamp of violent oppression rode Benjamin Ryan Tillman, one of the most repulsive, base, grotesque human beings to ever hold elected office in the United States. Tillman was a notorious white supremacist; he railed against the idea of having to pay his former slaves a wage, and forced them into onerous work contracts that kept them poor and without options — slavery by another name. He hated blacks and openly railed against them as subhuman animals at every opportunity, and subjected his workers to the lash even though it was no longer legal to do so. Most critically, he joined with the Sweetwater Sabre Club and the Redshirts, two of the most notorious terror gangs of the time, and took part in the massacre of black voters, militiamen, and even elected officials. He oversaw the brutal murder of dozens of blacks in South Carolina, and personally killed at least half a dozen himself. All of this came after the Civil War, when the law of the land recognized his victims as true American citizens with all the rights of an American; but democratically elected officials, upstanding soldiers who served their country, and innocent civilians attempting to exercise their Constitutional right to vote, Tillman murdered them all.

This is not history that is in dispute. It is a matter of plain and well-documented fact. Tillman himself bragged, not only of his contempt for blacks, but of his outright murder of them, until the day he died, including the entire duration of his terms as the governor of South Carolina and a United States senator. Lest anyone assume it excessively hyperbolic to refer to him as a terrorist should know that the description came from Tillman’s own mouth; he constantly boasted of his violence against blacks, making no secret of his contempt for decency, civility, and democracy. “We tried to overcome the (black) thirty-thousand majority by honest methods,” he lied, but discovering it to be a “mathematical impossibility”, he decided to “recover our liberty by fraud and violence”. Years later, in his autobiography, he frankly stated that “the purpose of our visit to Hamburg (where seven black militiamen were murdered) was to strike terror”. Two months later, he led his men into Ellenton, where as many as a hundred blacks were slaughtered, including a state senator.

So, when African-American students today complain about having to daily walk past a building named for this monster, they’re not talking about merely a figure in history who was susceptible to the ordinary bigotry of his time and place, or someone lucklessly entangled in the dismal economics of a slave state, or even a more outspoken than normal Southern white supremacist. They are talking about a man who was considered a violent thug even by the standards of the day; a self-admitted terrorist who led groups of armed rebels in a deadly campaign to overthrow the legitimate government, suppress the fair functioning of democracy, and grind their fellow countrymen into the dirt; a man who not only owned their ancestors, but once he was no longer allowed to do so, commenced to murdering them in numbers that exceed the bodycount of any mass murderer.

This is the armed terrorist of whom Clemson’s (white) Vice-President of Student affairs referred to as part of “the history of Clemson, and you can’t change the history”. This is the multiple murderer that the local news refers to as “a person with a background of prejudice”. This is the anti-democratic racial supremacist Kevin Hart is referring to when he says “it’s a tradition at Clemson University”, and tells us that “what we should really be focusing on” is “all he did for Clemson”. But this view of history requires a moral relativism leagues beyond that of the most leftist postmodernist: it is a fantastical whitewashing that claims no crime is too heinous, no massacre is too horrific that it can’t be balanced out if the perpetrator did something nice for white people. Neo-Confederates and Civil War revisionists will point to the corruption and greed of the postbellum South, but Reconstruction never wreaked anything near the havoc on innocent people that Ben Tillman did all by himself, let alone the combined horrors of hundreds of years of chattel slavery.

No one is asking that Benjamin Tillman be erased from historical memory. What the black students of Clemson are asking is that he be recognized for the monster that he was, and that, instead of being held up as a benefactor to education, he be presented in the historical record as what he was: a terrorist, a bigot, and a killer. Charles Manson is certainly in no danger of being scrubbed from our collective memory; we simply aren’t going to focus on the fact that he was charismatic and could write a catchy tune and name a city park after him. Adolf Hitler will never be forgotten by history, but we have sensibly chosen to remember that the terrible things he did far outweigh the fact that he kick-started the German economy, and have wisely decided not to go around naming schools after him. Asking that a murderer be called a murderer, and not glorified by forcing the descendants of his victims to walk, heads bowed, around a multi-million-dollar structure erected in his name, is not a elimination or a distortion of history; it is an admission and a recognition of history in a country that is increasingly forgetting how to do so.

Memrefuting

(in which I bring this blog back to the “safe, uncontroversial” territory of arguing with people who think they can solve NP-complete problems in polynomial time)

A few people have asked my opinion about “memcomputing”: a computing paradigm that’s being advertised, by its developers, as a way to solve NP-complete problems in polynomial time. According to the paper Memcomputing NP-complete problems in polynomial time using polynomial resources and collective states, memcomputing “is based on the brain-like notion that one can process and store information within the same units (memprocessors) by means of their mutual interactions.” The authors are explicit that, in their view, this idea allows the Subset Sum problem to be solved with polynomial resources, by exploring all 2n possible subsets in parallel, and that this refutes the Extended Church-Turing Thesis. They’ve actually built ‘memcomputers’ that solve small instances of Subset Sum, and they hope to scale them up, though they mention hardware limitations that have made doing so difficult—more about that later.

A bunch of people (on Hacker News, Reddit, and elsewhere) tried to explain the problems with the Subset Sum claim when the above preprint was posted to the arXiv last year. However, an overlapping set of authors has now simply repeated the claim, unmodified, in a feature article in this month’s Scientific American. Unfortunately the SciAm article is behind a paywall, but here’s the relevant passage:

Memcomputing really shows advantages when applied to one of the most difficult types of problems we know of in computer science: calculating all the properties of a large series of integers. This is the kind of challenge a computer faces when trying to decipher complex codes. For instance, give the computer 100 integers and then ask it to find at least one subset that adds up to zero. The computer would have to check all possible subsets and then sum all numbers in each subset. It would plow through each possible combination, one by one, which is an exponentially huge increase in processing time. If checking 10 integers took one second, 100 integers would take 1027 seconds—millions of trillions of years … [in contrast,] a memcomputer can calculate all subsets and sums in just one step, in true parallel fashion, because it does not have to shuttle them back and forth to a processor (or several processors) in a series of sequential steps. The single-step approach would take just a single second.

For those tuning in from home: in the Subset Sum problem, we’re given n integers a1,…,an, and we want to know whether there exists a subset of them that sums to a target integer k. (To avoid trivializing the problem, either k should be nonzero or else the subset should be required to be nonempty, a mistake in the passage quoted above.)

To solve Subset Sum in polynomial time, the basic idea of “memcomputing” is to generate waves at frequencies that encode the sums of all possible subsets of ai‘s, and then measure the resulting signal to see if there’s a frequency there that corresponds to k.

Alas, there’s a clear scalability problem that seems to me to completely kill this proposal, as a practical way of solving NP-complete problems. The problem is that the signal being measured is (in principle!) a sum of waves of exponentially many different frequencies. By measuring this wave and taking a Fourier transform, one will not be able to make out the individual frequencies until one has monitored the signal for an exponential amount of time. There are actually two issues here:

(1) Even if there were just a single frequency, measuring the frequency to exponential precision will take exponential time. This can be easily seen by contemplating even a moderately large n. Thus, suppose n=1000. Then we would need to measure a frequency to a precision of one part in ~21000. If the lowest frequency were (say) 1Hz, then we would be trying to distinguish frequencies that differ by far less than the Planck scale. But distinguishing frequencies that close would require so much energy that one would exceed the Schwarzschild limit and create a black hole! The alternative is to make the lowest frequency slower than the lifetime of the universe, causing an exponential blowup in the amount of time we need to run the experiment.

(2) Because there are exponentially many frequencies, the amplitude of each frequency will get attenuated by an exponential amount. Again, suppose that n=1000, so that we’re talking about attenuation by a ~2-1000 factor. Then given any amount of input radiation that could be gathered in physical universe, the expected amount of amplitude on each frequency would correspond to a microscopically small fraction of 1 photon — so again, it would take exponential time for us to notice any radiation at all on the frequency that interests us (unless we used an insensitive test that was liable to confuse that frequency with many other nearby frequencies).

What do the authors have to say about these issues? Here are the key passages from the above-mentioned paper:

all frequencies involved in the collective state (1) are dampened by the factor 2-n. In the case of the ideal machine, i.e., a noiseless machine, this would not represent an issue because no information is lost. On the contrary, when noise is accounted for, the exponential factor represents the hardest limitation of the experimentally fabricated machine, which we reiterate is a technological limit for this particular realization of a memcomputing machine but not for all of them …

In conclusion we have demonstrated experimentally a deterministic memcomputing machine that is able to solve an NP-complete problem in polynomial time (actually in one step) using only polynomial resources. The actual machine we built clearly suffers from technological limitations due to unavoidable noise that impair [sic] the scalability. This issue can, however, be overcome in other UMMs [universal memcomputing machines] using other ways to encode such information.

The trouble is that no other way to encode such information is ever mentioned. And that’s not an accident: as explained above, when n becomes even moderately large, this is no longer a hardware issue; it’s a fundamental physics issue.

It’s important to realize that the idea of solving NP-complete problems in polynomial time using an analog device is far from new: computer scientists discussed such ideas extensively in the 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, the whole point of my NP-complete Problems and Physical Reality paper was to survey the history of such attempts, and (hopefully!) to serve as a prophylactic against people making more such attempts without understanding the history. For computer scientists ultimately came to realize that all proposals along these lines simply “smuggle the exponentiality” somewhere that isn’t being explicitly considered, exactly like all proposals for perpetual-motion machines smuggle the entropy increase somewhere that isn’t being explicitly considered. The problem isn’t a practical one; it’s one of principle. And I find it unfortunate that the recent memcomputing papers show no awareness of this story.

(Incidentally, quantum computing is interesting precisely because, out of all “post-Extended-Church-Turing” computing proposals, it’s the only one for which we can’t articulate a clear physical reason why it won’t scale, analogous to the reasons given above for memcomputing. With quantum computing the tables are turned, with the skeptics forced to handwave about present-day practicalities, while the proponents wield the sharp steel of accepted physical law. But as readers of this blog well know, quantum computing doesn’t seem to promise the polynomial-time solution of NP-complete problems, only of more specialized problems.)

Money, Money, Everywhere, But Not A Cent To Spend

The DSM is written mostly by academics, which is why it gets so excited about distinctions like schizoid personality versus schizotypal personality. If it were written by clinicians, it might better reflect the sort of cases that make it into a hospital.

There would, for example, be an entire chapter on the scourge of ‘My Boyfriend Broke Up With Me’ spectrum disorders. More attention would get paid to the plague of chronic ‘I Got Angry At My Dad And Told Him I Was Going To Kill Myself To Freak Him Out And He Overreacted And Called The Cops And Now Here I Am In Hospital But Honestly I Didn’t Mean It’. Society would finally wake up to the epidemic of ‘I Wanted To Take My Medicine But My Hand Slipped And I Somehow Took The Entire Bottle All At Once Even Though I Would Never Do Something Like Intentionally Overdose’. And the sufferers of ‘This Patient Probably Has Some Kind Of Complicated Neurological Problem But Neurology Is Tired Of Trying To Figure It Out So They Have Declared It To Be Psychiatric’ might at last get some relief.

But the biggest change to the medical lexicon would be the introduction of ‘Poverty NOS’.

I recently got a patient, let’s call him Paul…

(all of my patient stories are vague composites of a bunch of people with details changed to protect privacy)

…who was in hospital after trying to hang himself. He said he was so deep in debt he was never going to get out. He’d been involved in a messy court case, had to hire a lawyer to defend himself, lawyer ended up running to the tune of several thousand dollars. He was a clerk at a clothing store, barely made minimum wage, maxed out his credit cards, then maxed out other credit cards paying off the first credit cards.

He didn’t seem to have major depressive disorder, but when someone comes in admitting to a serious suicide attempt, procedure says he gets committed. He wasn’t thrilled about this, saying if he missed work then he might lose his job and this was just going to make him further behind on his payments, but I checked with my attending and as usual the answer was “admit”.

Something especially bothered me about this case, and after thinking about it I’ve figured out what it is.

It’s not just that the psychiatric hospitalization won’t help and might hurt. That’s pretty common. The ‘My Boyfriend Broke Up With Me’s, the ‘I Got Angry At My Dad’s, unless they have some underlying disorder all of these people get limited value from the psychiatric system and tend to just sit in hospital for a couple of days, go to some group therapy, get asked a hundred times if they’re depressed, then go home. And then they’re still broken up with their boyfriend or still have a terrible relationship with their dad and the same thing’s going to happen again.

In this case, it was that – well, the guy is a minimum wage worker from inner city Detroit. He didn’t tell me exactly how much money this debt was, but from a couple of numbers he mentioned I got the impression it was in the ballpark of $5000. That might not seem like an attempt-suicide level of money to some people, but to this guy with his job the chance of ever paying it off seemed low enough that it wasn’t worth waiting and seeing.

So what bothered me is that psychiatric hospitalization costs about $1,000 a day. Average length of stay for a guy like him might be three to five days. So we were spending $5,000 on his psychiatric hospitalization, which was USELESS, so that we could send him out and he could attempt suicide again because of his $5,000 debt which he has no way of paying off. And probably end up in the hospital a second time, for that matter.

I assume that since he was poor, Medicaid paid his hospital bill. I’m not complaining that the cost of the hospital bill was added to his debt, I’m pretty sure it wasn’t, although in some other cases it would be. I’m complaining that here’s this guy, so desperate for money that he wants to kill himself over it, and he has to sit helplessly as we throw thousands of dollars at getting a parade of expensive doctors and nurses and social workers to talk to him, conclude that yup, his problem is definitely that he’s poor, and then throw him back out. I feel like this fails to be, as the buzzwords say, “patient-centered care”.

Problem is, you don’t have to be an economics PhD to realize that “give $5,000 to anyone who attempts suicide and says they need it” might create some bad incentives.

I have no good solution to this. Offering people who are so poor they want to kill themselves very expensive psychiatric care seems maybe a little better than doing nothing. But it also seems insulting, patronizing, paternalistic, wasteful, and occasionally heartbreaking.

And this is why I can never decide whether to identify as a libertarian or a liberal. On the one hand, top-down institutionalized bureaucracies seem so ridiculously inefficient at solving problems that it’s an outrage and a disaster. On the other hand, there are a lot of problems that really need solving, they don’t seem to have solved themselves yet, and governments are the only entity with enough coordination power to attempt the task.

Solution there, it seems to me, is to create unimpoverishable populaces. I think if we were to implement a Basic Income Guarantee we might save more money in psychiatric care than we think – since we compete with the prison system to be the warehouse for people who can’t make it out in the world and nobody knows what to do with. It might produce some of the same kind of savings as giving the homeless people houses. If I got fired because we’d solved all the problems relating to poverty, and the population of seriously mentally ill people was too small to support the current number of psychiatrists, that would be a pretty neat way to go.

MADONNA – “American Pie”

#850, 11th March 2000

I can’t remember, did I cry when I heard about Madonna’s “Pie”? To claim I did would be a lie, in fact I likely smiled. A dance-pop version of one of the great rock totems, by an artist on a creative roll, teamed with one of the most sympathetic producers of her career? How could it possibly fail to enrage my foes and gladden my friends? In my head existed a version of “American Pie” that had a shot at being a great single, and would at least end up a marvellous joke. Yet neither outcome came true.

I can’t remember, did I cry when I heard about Madonna’s “Pie”? To claim I did would be a lie, in fact I likely smiled. A dance-pop version of one of the great rock totems, by an artist on a creative roll, teamed with one of the most sympathetic producers of her career? How could it possibly fail to enrage my foes and gladden my friends? In my head existed a version of “American Pie” that had a shot at being a great single, and would at least end up a marvellous joke. Yet neither outcome came true.

The question of whether or not Madonna screws up “American Pie” is easily answered: yes. How it goes wrong for her is a bit more interesting. But most intriguing of all is what she saw in it to make her want to try. Yes, Rupert Everett put her up to it. But Madonna’s discography is not otherwise chock-ful of bad singles recorded as favours to actor mates. She is 41 at this point, a remarkably shrewd individual at a career high in terms of creative control: even if this is a complete whim, it’s a whim she carried through. Why?

To find out I need to dig into what, exactly, the original “American Pie” was. Don McLean’s lament for the death in 1958 of Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and The Big Bopper, most simply. (And it does a touching, clumsy job at that: “Bad news on the doorstep / I couldn’t take one more step.”) Of course that’s only the beginning. He turns that inciting incident into a kind of myth-cycle for the entire 1960s, told through a series of riddles and coded references to the era’s pop artistocracy. Which led to the song’s enduring appeal to some people who’d lived through that decade (or wished they had): not just a validation, but a puzzle-book, a thing to be “interpreted”. And by the same token, “American Pie” became widely hated by many born after that, whose response to eight minutes of jesters and quartets and whisky and rye was, roughly, “Why do I care about this shit?”

Looked at now, “American Pie”’s status as a boomer rosetta stone is a little embarrassing, but also fascinating. Even by the CD era, let alone the Spotify one, the references seemed dreadfully on the nose: “The birds flew off with a fallout shelter / Eight miles high and falling fast”. What can the answer be, O Sphinx? But in 1972 these might have played as genuine riddles, triggers for memory and reinforcements of the importance of what had happened: the sense that rock could be – deserved to be! – treated as legend. Even so the pile-up of call-backs is overwhelming, drowning most of the song’s sense. There’s a term from comics and sci-fi fandom for this particular impulse to lard a work with continuity references, determinedly excluding the not-we from the party: fanwank. And “American Pie” is sixties fanwank of the purest kind.

But every fan also has an agenda. Between the too-many lines of “American Pie” are buried schisms and debates. We’re listening, after all, to a history of the 60s in which the music is already dead, killed not when the Beatles broke up but around the time they met. “American Pie” is as much a ghost story as a celebration, and there’s a vengeful purism to McLean’s take on rock music and its decade. In some ways he toes baby boomer orthodoxy – the sixties end at Altamont – but in others he’s a heretic: the most visceral part of the song comes when he watches, furious and bitter, as Mick Jagger dances onstage, and names him Satan. Buried here is an earlier question – what has happened to the magic of rock’n’roll? – a split among the fifties and sixties generation themselves, which the party of “American Pie” seemed to be losing by the time the song was recorded. The song’s side of the schism, I’d say, holds that rock’n’roll hit teenage perfection in the mid-50s, and the sixties saw its decadence and decline. “American Pie” loves the sixties, breathes the sixties, but in this one crucial way has more in common with its haters than its fans.

Madonna, in a theological dispute between Buddy Holly and Mick Jagger, is surely of the devil’s party. But despite my initial excitement, I don’t think she was exactly trolling when she made it (and McLean gushed over her version anyway). I doubt she had much respect for “American Pie”’s meandering retread of sixties pop history, but she certainly had a use for it. In 1999 she’d enjoyed a large, worldwide hit with “Beautiful Stranger”, another Orbit production from the second Austin Powers movie. “Stranger” was a triumph – Orbit’s production managed to capture and update a swirling essence of sixties pop and clubland without actually sounding much like anything from those days. In a stroke she’d done what years of dogged Britrock effort had failed to: successfully modernise the 1960s.

So why not try and hit that spot a second time, with a song absolutely steeped in the era? William Orbit’s arrangement on “American Pie” isn’t as dense as the techno-psychedelic pop sheen he gave “Beautiful Stranger”, but its gyrating keyboard line, occasional hints of fuzz bass, and synthesised Rickenbackers suggest he’s going for a similar hit of lightly retrofied bliss. But it doesn’t work: “American Pie” is comparatively lifeless, and the instrumental touches that seemed like delightful presents to the listener on “Stranger” feel like awkward marking time here, waiting for a misguided song to end.

Does the problem lie in Madonna’s editing? She strips out most of the blind-item content – a wise move – to leave stuff about music and dancing and a bit of religion: her chosen territories. That isn’t a bad way to cut the song – especially as it positions her as the keeper of music’s flame within the record – but even trimmed a lot of McLean’s lyrics are still too idiosyncratic for another singer to get much grip on. What can Madonna do with “I was a lonely teenage broncin’-buck / With a pink carnation and a pick-up truck”? Her best, but the singer and the song don’t fit.

The wider issue, though, is the translation of folk-rock into dance-pop. McLean’s lines are long and rangy, and an acoustic accompaniment gives him space to stretch, play with the cadences, tell a story, even if it is a dumb story full of smarmy riddles. William Orbit’s elegant, clockwork productions are inimical to that, pushing McLean’s words back into line and tempting Madonna into the regulated, autocue reading she gives. Even the song’s very good lines – “I know that you’re in love with him / Cos I saw you dancing in the gym” – get swallowed up by the metre, and Madonna barely bothers to lend them any expression. The restrained, trained singing voice she used on “Frozen” and “Substitute For Love” lets her down badly here. Ultimately, “American Pie” works – for good or bad – as a shaggy dog tale its singer believes in. If this was the only version that existed, nobody would even hate it.

There’s a final mistake, too, in following “Stranger” with this. “American Pie” is a song based on the idea that the sixties mattered – that the details of their story and struggles were vital. “Beautiful Stranger”, and Austin Powers for that matter, are assertions that the sixties now matter only as an aesthetic. They treat the decade the way the hippies treated the Victorian and Edwardian era: a look, a texture, little more. It was an inevitable shift, and a relief. Covering “American Pie” – reducing the ultimate sixties-as-content record to a sixties-as-aesthetic one – might have been a smart way of underlining that, but the song beats her, forcing her to relive a fight she really has no interest in. She knew it, too – “American Pie” was left off the next Greatest Hits record, and even her successful partnership with Orbit wouldn’t last much longer. Time, once again, to move forward.

Legends of the Dork Knight

"Gothic" by Grant Morrison and Klaus Janson

If "Shaman" was an ambitious misfire, "Gothic" is the story where Legends of the Dark Knight finally came into its own and fully embraced its remit. It's important to remember that, back in 1989, there really wasn't much in the way of a track record for Batman stories like this. The three models for "mature readers" (I'm putting that phrase in necessary scare-quotes) Batman stories that LotDK was initially pulling from were 1988's The Killing Joke, 1987's "Year One," and 1986's The Dark Knight Returns. The same year that LotDK premiered also saw the release of Grant Morrison and Dave McKean's Arkham Asylum graphic novel. The idea of a Batman story designed to be read by an audience that didn't include young children was still new. We take it for granted now that many - if not, unfortunately, most - Batman stories currently published just aren't appropriate for kids. But back then the idea was, pardon the pun, novel, and it was this revelation that served as the inspiration for hundreds of subsequent "Comics Aren't Just For Kids Anymore" headlines. It was a strange idea for many, many people to wrap their heads around.

Even though "Shaman" lacked the Comics Code seal, there was nothing in the story that would have proved problematic for the Authority. Denny O'Neil was an old hand, and even though the story was concerned with "heavy" themes such as myth, cultural theft, and ritual murder, it was still essentially a Batman story of the kind that could have been told at any point in the previous twenty years, just told with a darker color palette. Not so "Gothic." This was a story that couldn't have been told with pre-1986 Batman. The violence, the intensity, the presence of explicit violence and (not so explicit but still upsetting) sex was new. It didn't go as far as Arkham Asylum, but it also wasn't anywhere near as abstruse. Although many of Morrison's early habits were well in place, the story was more brutal and direct than its more highbrow cousin. This was a murder mystery that touched on child murder, sexual abuse, satanism, and rape in the course of its unraveling.

Morrison has written many Batman stories in his career, and much of his later work is prefigured in "Gothic." For one, Morrison wasn't afraid to cross the line separating Batman's mundane crime-ridden Gotham from the kind of supernatural horror elements exemplified by the story's villain, Mr. Whisper. The idea that Gotham is somehow a genuinely haunted, specially cursed placed was one that would become more and more central to the mythos. Now it's often a given that Gotham city, rather than merely an exaggerated vision of 1970s urban hell New York, contains some kind of Mephistophelian affinity to the literal hell. (For modern examples, see Snyder and Capullo's Batman, as well as Batman Eternal.) Morrison also introduces the idea that Thomas Wayne was a deeper and more significant figure in Gotham history than previous writers had intimated. And finally, even though "Gothic" is close to being a straight horror story, Morrison also has fun mixing and matching a few motifs from previous Batman eras: in the midst of a heavy supernatural mystery, he finds time to strap our hero into a Rube Goldberg deathtrap straight out of the 1960s TV show. The idea that all of Batman's diverse and thematically inconsistent histories coexisted as parts of the character's development was one that Morrison would return to later.

The story begins with the a series of murders of Gotham's most powerful criminals. In desperation these criminals turn for protection to Batman, who scoffs at their attempts at negotiation before setting out to hunt the killer himself. (Oh, yeah, I guess these are spoilers for a 25-year-old Batman story?) Morrison performs an extremely clever maneuver here: in the early pages he leads the reader to believe the story will focus on the crime lords being hunted and killed by some mysterious force. But it turns out that the crime lords' purpose in the story is mainly to give Batman (and the audience) a red herring. The actual plot has little to do with the mob bosses. Mr. Whisper is killing them, but more out of boredom while sitting around Gotham waiting for his real plan to kick in.

The "real" plan actually involves a 300-year old serial killer who made a deal with the devil, and his plan to murder every man, woman, and child in Gotham as a means of escaping this obligation. There are allusions peppered throughout, from Marlowe's Doctor Faustus to de Sade's 120 Days of Sodom, the latter of which he would return to in the second arc of The Invisibles. Meanwhile, the catalyst for Mr. Whisper's crusade of vengeance against Gotham's underworld is revealed to be, basically, the plot of Fritz Lang's M. Morrison here is still operating very much in the mode of fellow "British Invasion" writers Moore and Gaiman - processing literary and artistic influences in a very literal-minded way, plucking plots and themes directly from older works to create a thick metatextual stew. Morrison would, of course, largely outgrow this tendency over the course of the next decade, with the aforementioned Invisibles acting as his own version of The Sandman, a means for a young creator of digesting and reflecting a large mass of influences through the lens of familiar genre fiction signifiers. Like Moore and Gaiman, Morrison would become a far more subtle writer with age, but his earlier work retains a pleasing density sometimes missing from his later, more streamlined efforts.