Little Soldiers is a book by Lenora Chu about the Chinese education system. I haven’t read it. This is a review of Dormin111’s review of Little Soldiers.

Dormin describes the “plot”: The author is a second-generation Chinese-American woman, raised by demanding Asian parents. Her parents made her work herself to the bone to get perfect grades in school, practice piano, get into Ivy League schools, etc. She resisted and resented the hell she was forced to go through (though she got into Stanford, so she couldn’t have resisted too hard).

Skip a decade. She is grown up, married, and has a three year old child. Her husband (a white guy named Rob) gets a job in China, so they move to Shanghai. She wants their three-year-old son to be bilingual/bicultural, so she enrolls him in Soong Qing Ling, the Harvard of Chinese preschools. The book is about her experiences there and what it taught her about various aspects of Chinese education. Like the lunches:

During his first week at Soong Qing Ling, Rainey began complaining to his mom about eating eggs. This puzzled Lenora because as far as she knew, Rainey refused to eat eggs and never did so at home. But somehow he was eating them at school.

After much coaxing (three-year-olds aren’t especially articulate), Lenora discovered that Rainey was being force-fed eggs. By his telling, every day at school, Rainey’s teacher would pass hardboiled eggs to all students and order them to eat. When Rainey refused (as he always did), the teacher would grab the egg and shove it in his mouth. When Rainey spit the egg out (as he always did), the teacher would do the same thing. This cycle would repeat 3-5 times with louder yelling from the teacher each time until Rainey surrendered and ate the egg.

Outraged, Lenora stormed to the school the next day and approached the teacher in the morning as she dropped Rainey off. Lenora demanded to know if Rainey was telling the truth – was this teacher literally forcing food into her three-year-old son’s mouth and verbally berating him until he ate it. The teacher didn’t even bother looking at Lenora as she calmly explained that eggs are healthy and that it was important for children to eat them. When Lenora demanded she stop force-feeding her son, the teacher refused and walked away.

Or the seating:

As Lenora hears more crazy stories from her son and friends, she keeps coming back to one question: “what does Rainey actually do in school?” Lenora tries to ask Rainey, but he always replies, “we sit still.” He also occasionally mentions painting and eating, but that’s it.

So Lenora goes to Rainey’s teacher one day and asks to sit in on classes to observe. Lenora is told that this is not possible. So she asks if she can know a little more about what the school is teaching Rainey. The teacher tells her that she is already told everything she needs to know, and that this is the “Chinese way.”

Since Lenora couldn’t get a look into Soong Qing Ling, she went to another local school and bribed her way into a classroom-observation post with some well-placed handbags. She discovered that Rainey was basically right. Chinese preschool really does seem to consist of sitting still. Unless given different orders, all students were required to sit in their seats with their arms at their sides, and their feet flat on a line of tape on the ground. This is not an easy task for three-year-olds.

There were two teachers in the classroom with a classic good cop/bad cop dynamic. The good cop stood in the front of the room with the desks splayed out before her. She would give simple instructions like orders to get food, water, or sometimes paint, though usually she said nothing at all. The bad cop was another teacher who prowled the classroom. Any time she saw a student remove a foot from the line, move arms from his side, or otherwise deviate from the instructions, she would yell at the student to fall back in line. Lenora spent about a week watching tiny kids get screamed at for trying to get water, shifting in their chairs, or talking to classmates.

Or art class:

When Lenora sat in on a kindergarten class, she witnessed an art lesson where the students were taught how to draw rain. The nice teacher drew raindrops on a whiteboard, showing precisely where to start and end each stroke to form a tear-drop shape. When it was the students’ turns, they had to perfectly replicate her raindrop. Over and over again. Same start and end points. Same curves. For an hour. No student could draw anything else. Any student who did anything different would be yelled at and told to start over.

The point of this exercise was not to teach students how to draw raindrops. Drawing raindrops is not an important life skill, and drawing them in a particular way is especially not important. Even the three-year-old students in the class seemed to realize this as many immediately created their own custom raindrop shapes and drew landscapes, all to be crushed under the mean teacher’s admonishment. The real point of the exercise was to teach students to follow directions from an authority figure. But more than that, the point was to follow pointless and arbitrary directions. The more pointless and arbitrary the directions are, the more willpower is required to follow them.

Chinese people presumably put up with this because it makes sense within their culture; why did Chu put up with it? Dormin half-jokingly suggests maybe she really wanted to write the book she eventually wrote, and this was her research. But Chu herself says it eventually got results:

After spending 75% of the book relentlessly complaining about her son’s Chinese education, with the occasional anecdote about how horrible her own culturally Chinese upbringing was, Lenora decides Chinese schools aren’t so bad.

After a few years in China, Rainey changed. Though Lenora constantly worried if Rainey’s creativity and leadership potential was being snuffed out, she couldn’t help but be impressed by his emerging self-control. He could sit still for longer. He always greeted people politely. He finished eating his food. He asked permission a lot.

Lenora didn’t realize what Rainey had become until she took him back to the US for a few weeks to visit family. There, the contrast between Rainey and his same-aged American counterparts become stark. Lenora’s friends’ kids ate junk food all day while Rainey asked for vegetables. They couldn’t read or do basic addition while Rainey was close to being bilingual and had started double-digit addition and subtraction by first grade. They wandered obliviously in their own worlds while Rainey’s Chinese grandparents were thrilled to receive respectful greetings every time Rainey entered the room […]

What really sold Lenora on Chinese education was that it apparently worked. At the time of writing the book, Shanghai was scoring first place in the world on the PISA exams, beating heavy-hitters like Norway and Singapore. Supposedly, education scholars and professionals all over the world were looking at China for wisdom. They all saw the bad, but they saw a lot of good too.

(before going forward, I should interject that China’s great PISA scores are kind of fake. China struck a deal with the OECD (the group that administers PISA) to let it conduct testing only in its four richest and best-educated provinces. Rich and well-educated places always do well on PISA. That China’s four best provinces outperform the average score of other countries is unsurprising. This article points out that if the US were allowed to enter only its best-educated state (Massachussetts, obviously) we would be right up there with China. So this probably isn’t as impressive as Ms. Chu thinks.)

This is just a sample of the great stuff in Dormin’s review of Little Soldiers, and I strongly recommend you read the whole thing. You should also read the comments, which point out that this may be more about a few elite Chinese schools than about an entire country. But I want to use these excerpts as a jumping-off point to talk about the US education system, unschooling, and child development in general.

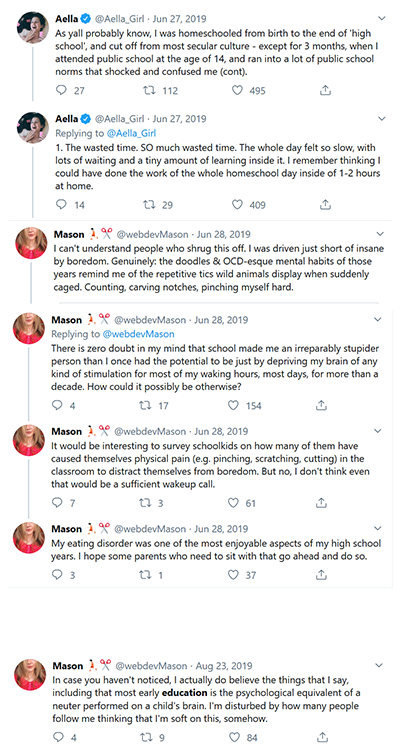

I predict most of my Bay Area friends would hate the Chinese education system as Chu describes it. I predict this because they already hate the US education system, which is only like 10% as bad. I’m especially thinking of @webdevmason and @michaelblume, who often write about the ways American education is frustrating, regressive, and authoritarian. Bright-eyed, curious kids come in. They spend thirteenish years getting told to show their work, being punished for reading ahead in the textbook, and otherwise having their innate love of learning drummed out of them in favor of endless mass-produced homework assignments (five pages, single-spaced, make sure you use the right number of topic sentences).

People with this position usually make two claims. One, US public school as it currently exists is awful, basically institutionalized child abuse. Two, this is bad for the economy. I’ve been through too much school myself to feel like challenging the first, so I want to focus on the second.

Salman Khan, John Gatto, and other education rebels trace the current school systems back to the Prussians, who invented compulsory education to prepare children for a career as infantrymen or factory workers. It’s a great story. Like most great stories, it’s kind of false. But like most kind-of-false things that catch on, it has an element of truth. Children who can sit still in a classroom and do what their teachers say are well-placed to become adults who can sit still in an open office and do what their bosses say. So (according to this logic), even if our schools are awful, they were well-suited to the Industrial Age economy. Some hypothetical mash-up of Otto von Bismarck and Voldemort, who wanted the country to produce as much as possible and didn’t care how many children’s souls were crushed in the process, might at least endorse the education system on widget-maximization grounds.

But (these same people argue), the Industrial Age is over. The most important skills now are entrepreneurship and creative problem solving. Reinventing yourself, selling yourself, carving out a new niche for yourself. Figuring out what’s going to be the next big thing and pursuing it without anyone else watching over you. We’re in XKCD’s world now, where 900 hours of classes and 400 hours of homework matter less to your career success than one weekend messing around with a programming language in 11th grade. The Prussian model of education stamps out the kind of independent agency that could help people navigate the weird, formless 21st century world.

How might the personified Chinese education system respond?

What if it said “I don’t know what you 老外 are doing in America, but I’m not crushing anybody. I’m just telling kids to sit here drawing 1,000 raindrops in a row without moving or protesting. If after that you decide you don’t want to found the next Uber, that’s on you. But if you do decide to found the next Uber, I will have taught you the most important skill: discpline. Learning how to sit still and obey others is the necessary prerequisite to learning how to sit still and obey yourself.”

If it was really mean, it might go further. “I notice most of you Americans suck at this skill. I notice you’re always whining about how you don’t have enough discipline to pursue your interests. Some of you are writers who spend years fantasizing about the novel you’re going to publish, but can never quite bring yourself to put pen to paper. Others want to learn another language, but reject real work in favor of phone apps that promise to ‘gamify’ staying at a 101 level for the rest of your life. You don’t need to feel bad about having no self-control; after all, nobody taught you any. If you’d gone to 宋庆龄幼儿园, you would have spent your formative years learning to sit still and focus, having your natural impulse to slack off squeezed out of you. Then you could have pushed through and written your novel, or learned 官話, or if you wanted to start Uber you could start Uber. At the very least you’d be doing something other than lying in bed browsing Reddit posts about how adulting is hard.”

My Bay Area friends treat people as naturally motivated, and assume that if someone acts unmotivated, it’s because they’ve spent so long being taught to suppress their own desires that they’ve lost touch with innate enthusiasm. Personified China treats people as naturally unmotivated, and assumes that if someone acts unmotivated, it’s because they haven’t been trained to pursue a goal determinedly without getting blown around by every passing whim.

What evidence is there in favor of one education system or the other?

I can’t find any good studies directly supporting or opposing either of these claims. The best I can do is The Development Of Executive Functioning And Theory Of Mind: A Comparison Of Chinese And US Preschoolers. They find that on various tests of executive function, “Chinese [preschool-age] children’s performance was consistently on par with that of US children who were on average 6 months older” (other sources say 1-2 years). But lots of interventions change things in childhood; this isn’t interesting unless it persists into adulthood, and I don’t see any work on this. This study on racial differences in personality traits found weak and inconsistent white-Asian differences on adult conscientiousness, but the Asian sample was Asian-American and differences in education were probably pretty minor.

What about circumstantial evidence?

First and most important, since extreme cultivation of discipline vs. laissez-faire childrearing is a property of parents as much as schools, any claimed effect would run afoul of all the twin studies showing that shared environment has few long-term effects on any trait. For example, this meta-analysis of factors affecting self-control that finds “no or very little influence of the shared environment on the variance in self-control”. But we can always invoke the usual loophole in shared environment findings: maybe the US doesn’t contain anything as extreme as the Chinese education system, so US-only studies can’t capture its effects.

Second, both Westerners and Chinese seem to include some very impressive and some less impressive people. It certainly doesn’t seem wrong to say that Chinese people seem more diligent and Westerners seem more independent, but there are so many potential biases at work that I would hate to take this too seriously as evidence for or against one form of education. Also, Chinese-Americans who are educated in US schools also seem more diligent than white Americans, so maybe the education system doesn’t contribute too much to this. Maybe Chinese culture promotes diligence better in general, this causes diligence-focused school systems, but the diligence-focused school systems don’t themselves cause the diligence.

Third, we could try to find more extreme versions on both sides and see what happens there. Pre-industrial populations with no education were famously bad at the discipline needed for factory work. From Pseudoerasmus:

The earliest factory workers were lacking in what Mokyr & Voth call “discipline capital” — non-cognitive ‘skills’ like punctuality, sobriety, reliability, docility, and pliability. Whether they had been peasants or artisans, early workers were new to industrial work habits and they had a strong preference for autonomous work arrangements. They were accustomed to setting their own pace of work in farming, domestic outwork, or artisanal workshops, and disliked the time rules and strict supervision of the factories.

All this is consistent with colourful descriptions of the early history of the textile industry in the Global South, including Japan. Mills were described as places of chaos and disorder. They were supposedly filled with workers ‘idling’, ‘loitering’, ‘socialising’, smoking, tea-drinking, or just disappeared for the day. In Japan, “twenty percent of the female operatives…absent themselves after they receive their monthly pay check” (Saxonhouse & Kiyokawa 1978). In Shanghai, it was said female mill workers could be found breast-feeding infants during work hours (Cochran 2000). Or at Mumbai mills, workers “bathed, washed clothes, ate his meals, and took naps” (Gupta 2011).

But this could be as much about expectations as about abilities.

Which historical culture had the most authoritarian-instillment-of-virtue-focused approach to child-rearing? Surely the New England Puritans were up there – remember that eg Puritan parents would traditionally send children away to be raised by other families, in the hopes that the lack of familiarity would make the child behave better”. They certainly ended out industrious. But they were also creative and self-motivated, sometimes almost hilariously so. On the other hand, I’m not sure that the Puritans who ended up incredibly creative were exactly the same Puritans who suffered extreme strict child-rearing – there seems about a century gulf between the evidence of authoritarian parenting in the 1600s and the crop of geniuses born in the late 1700s – so I’m not sure how seriously to take this.

Fourth, we could look at US trends over time. Both US parenting and US schooling seem to be getting less authoritarian over time; 31 states have banned corporal punishment since 1970, and the teachers I know confirm a shift away from most forms of discipline. Over the same time period, children have gotten weirdly better behaved – less crime, less teenage pregnancy, more willing to jump through various stupid hoops to get into a good college. This seems to contradict the Chinese theory – the children are no worse at controlling their impulses. But there are other findings that contradict the Bay Area theory – entrepreneurship is decreasing; more top students are choosing to go work for a boss at a big bank rather than go do something weird. I think the better behavior is probably just caused by lower lead; I have no idea why people are more risk-averse. Secular decline in testosterone, maybe?

Fifth, we could look at research on the effects of preschool more generally. Some studies find that US preschools do not make children smarter, but still improve life outcomes like graduation rates, crime rates, and employment. Although there are lots of theories about the “noncognitive skills” that accomplish this (including that they don’t exist and the improvement is an artifact of bad experimental technique), this is certainly consistent with preschool teaching children discipline at a critical window. If this hypothesis were true, the effect of preschool would be much larger in China, but I don’t know of any Chinese studies on the topic.

Sixth, we could look at the research on meditation for very young kids. The Chinese theory casts preschool as a sort of dark-side form of mindfulness. In traditional Buddhist settings, monks would sit perfectly still and concentrate on the most boring thing imaginable, and the head monk would slap them with a bamboo stick if they moved. The resemblance to the school system is uncanny. So maybe school’s effects on self-control could be modeled as a sort of less-intense but much-more-drawn-out meditation session. Unfortunately, the studies surrounding mindfulness in kids are crap, so this doesn’t help either.

Really none of this seems very helpful and we’re kind of left with our priors. And maybe one of our priors is “don’t abuse children”, so there’s that.

But what about the Polgars? They turned all three of their children into chess prodigies through a strategy that seemed based around exposing them to absurd amounts of chess at a very young age. If we generalize, it does look like very young children might have very plastic minds that you can shape through out-of-distribution experiences. But Lazslo Polgar insisted that his technique didn’t use force; the point was to interest his children in the material so avidly that they inflicted near-Chinese levels of intensity on themselves in order to study it more successfully.

One problem with the physical universe is that even after you study a question in depth and decide more evidence is needed, there are still real children you have to educate one way or the other. I have no general solution for this, but the Polgar strategy seems like a good deal if you can pull it off.