Chait argued that this lack of sufficient "positive habits and behaviors" stemmed from cultural echoes of past harms, which now exist "independent" of white supremacy. Chait now concedes that this assertion is unsupportable and attempts to recast his original argument:

The phrase "culture of poverty" doesn't actually appear in Chait's original argument. Nor should it—the history he cites was experienced by all variety of African Americans, poor or not. Moreover, the majority of poor people in America have neither the experience of segregation nor slavery in their background. Chait is conflating two different things: black culture—which was shaped by, and requires, all the forces he named; and "a culture of poverty," which requires none of them.

That conflation undergirds his latest column. Chait paraphrases my argument that "there is no such thing as a culture of poverty." His evidence of this is quoting me attacking the "the notion that black culture is part of the problem." This evidence only works if you believe "black culture" and "a culture of poverty" are somehow interchangeable.

I think one can safely call that an element of a kind of street culture. It's also an element which—once one leaves the streets—is a great impediment. "I ain't no punk" may shield you from neighborhood violence. But it can not shield you from algebra, when your teacher tries to correct you. It can not shield you from losing hours, when your supervisor corrects your work. And it would not have shielded me from unemployment, after I cold-cocked a guy over a blog post.

Chait calls this one of the most "memorable essays" he's ever read. This is too kind—both to my writing and to his memory. Chait reads the piece as evidence of having "grown up around cultural norms that inhibited economic success." In fact, my behavior was the result of having grown up around cultural norms that enabled my survival. I said as much in the original piece:

The problem is that rarely do such critiques ask why anyone would embrace such values. Moreover, they tend to assume that there's something uniquely "black" about those values, and their the embrace. If you are a young person living in an environment where violence is frequent and random, the willingness to meet any hint of violence with yet more violence is a shield.

I repeated the same thing two years later:

Using the wrong tool for the job is a problem that extends beyond the dining room. The set of practices required for a young man to secure his safety on the streets of his troubled neighborhood are not the same as those required to place him on an honor roll, and these are not the same as the set of practices required to write the great American novel. The way to guide him through this transition is not to insult his native language.

And then again last May:

For black men like us, the feeling of having something to lose, beyond honor and face, is foreign. We grew up in communities—New York, Baltimore, Chicago—where the Code of the Streets was the first code we learned. Respect and reputation are everything there. These values are often denigrated by people who have never been punched in the face. But when you live around violence there is no opting out. A reputation for meeting violence with violence is a shield. That protection increases when you are part of a crew with that same mind-set. This is obviously not a public health solution, but within its context, the Code is logical. Outside of its context, the Code is ridiculous.

The point has obviously eluded Chait. Instead of considering that I may well have been responding to my actual lived circumstances, Chait chooses to assume that I was responding to some inscrutable call of the wild:

When the imprint of this culture was nearly strong enough to derail the career of a writer as brilliant as Coates, we are talking about a powerful force, indeed.

What's missed here is that the very culture Chait derides might well be the reason why I am sitting here debating him in the first place. That culture contained a variety of values and practices. "I ain't no punk" was one of them. "Know your history" was another. "Words are beautiful" was another still. The key is cultural dexterity—understanding when to emphasize which values, and when to employ which practices.

Chait endorses a blunter approach:

The circa-2008 Ta-Nehisi Coates was neither irresponsible nor immoral. Rather, he had grown up around cultural norms that inhibited economic success. People are the products of their environment. Environments are amenable to public policy. Some of the most successful anti-poverty initiatives, like the Harlem Children’s Zone or the KIPP schools, are designed around the premise that children raised in concentrated poverty need to be taught middle class norms.

No, they need to be taught that all norms are not transferable into all worlds. In my case, physical assertiveness might save you on the street but not beyond it. At the same time, other values are transferrable and highly useful. The "cultural norms" of my community also asserted that much of what my country believes about itself is a lie. In the spirit of Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, and Malcolm X, it was my responsibility to live, prosper, and attack the lie. Those values saved me on the street, and they sustain me in this present moment.

People who take a strict binary view of culture ("culture of privilege = awesome; culture of poverty = fail") are afflicted by the provincialism of privilege and thus vastly underestimate the dynamism of the greater world. They extoll "middle-class values" to the ignorance and exclusion of all others. To understand, you must imagine what it means to confront algebra in the morning and "Shorty, can I see your bike?" in the afternoon. It's very nice to talk about "middle-class values" when that describes your small, limited world. But when your grandmother lives in one hood and your coworkers live another, you generally need something more than "middle-class values." You need to be bilingual.

In 2008, I was living in central Harlem, an area of New York whose demographics closely mirrored the demographics of my youth. The practices I brought to bear in that tent were not artifacts. I was not under a spell of pathology. I was employing the tools I used to navigate the everyday world I lived. It just so happened that the world in which I worked was different. As I said in that original piece, "There is nothing particularly black about this." I strongly suspect that white people who've grown up around entrenched poverty and violence will find that there are certain practices that safeguard them at home but not so much as they journey out. This point is erased if you believe that "black culture" is simply another way of saying "culture of poverty."

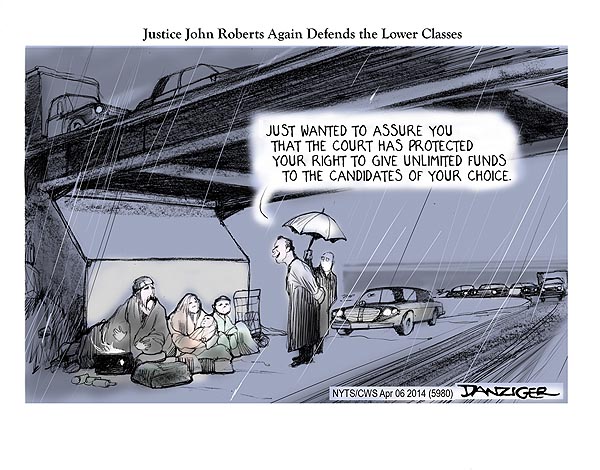

This elision is not particular to Chait. In the 1960s, when 20 percent of black children were found to be born out of wedlock, progressives went to war over the "tangle of pathologies" choking black America. Today, 30 percent of white children are being born out of wedlock. The reaction to this shift has been considerably more muted. This makes sense if you believe that pathology is something reserved for black people. When The New Republic wanted to dramatize the evils of AFDC, there was really no doubt about whose portrait they'd pick.

Accepting the premise that "black culture" and "a culture of poverty" are interchangeable also has the benefit of making the president's rhetoric much more understandable. One begins to get why the president would address a group of graduates from an elite black college on the tendency of young men in the black community to make "bad choices." Or why the president goes before black audiences and laments the fact that the proportion of single-parent households has doubled, and carry no such message to white audiences—despite the fact that single parenthood is growing fastest among whites. And you can understand how an initiative that began with the killing of a black boy who was not poor, and who had a loving father, becomes fuel for the assertion that "nothing keeps a young man out of trouble like a father." In his best work, Chait mercilessly dissects this kind of intellectual slipperiness. Now we find him applauding it and reifying it.

"Culture is hard, though not impossible, to quantify," writes Chait. "Which does not mean it doesn’t exist." Indeed. I have done my best to identify specific cultural practices and outline how they work in different worlds. Much of that evidence is built on memoir, and thus necessarily subject to an uncomfortable vagueness.

But quantifying the breadth and effect of white supremacy suffers no such drawbacks. Some of our most celebrated scholarship—Battle Cry of Freedom, Reconstruction, The Making of the Second Ghetto, The Warmth of Other Suns, At the Hands of Persons Unknown, Family Properties, Confederate Reckoning, Black Wealth/White Wealth, American Apartheid, Crabgrass Frontier, The Origins of the Urban Crisis, When and Where I Enter, When Affirmative Action Was White—is directed toward, with great specificity, outlining the reach and effects of white supremacy.

It is not wholly surprising that Barack Obama tends not to focus on this literature, whatever its merits. I do not expect the president of the United States to make a habit of speaking unvarnished and uncomfortable truths. (Though he is often brilliant when he does.) Of course removing white supremacy from the equation puts Barack Obama in the odd position of focusing on that which is hardest to evidence, while slighting that which is clearly known.

Jonathan Chait is not a politician. He needs neither to assemble a 60-vote majority nor worry about his words affecting the midterms. I'm happy that Chait decided to engage me here on a subject that he, himself, confesses is hard to quantify. I wish I'd had his input over the past few months when I was poring over redlining maps and grappling with the racism implicit in the New Deal. I wish I'd had his input when I was attempting to understand what it meant that in 1860 this country's most valuable asset was enslaved human beings. I think had we engaged each other then, he might well not have written something like this:

It is hard to explain how the United States has progressed from chattel slavery to emancipation to the end of lynching to the end of legal segregation to electing an African-American president if America has “rarely” been the ally of African-Americans and “often” its nemesis. It is one thing to notice the persistence of racism, quite another to interpret the history of black America as mainly one of continuity rather than mainly one of progress.

This certainly is a specimen of progress—much like the ill-tempered man might "progress" from shooting at his neighbors to clubbing them and then finally settle on simply robbing them. His victims, bloodied, beaten, and pilfered, might view his "progress" differently. Effectively Chait's rendition of history amounts to, "How can you say I have a history of violence given that I've repeatedly stopped pummeling you?"

Chait's jaunty and uplifting narrative flattens out the chaos of history under the cheerful rubric of American progress. The actual events are more complicated. It's true, for instance, that slavery was legal in the United States in 1860 and five years later it was not. That is because a clique of slaveholders greatly overestimated its own power and decided to go to war with its country. Had the Union soundly and quickly defeated the Confederacy, it's very likely that slavery would have remained. Instead the war dragged on, and the Union was forced to employ blacks in its ranks. The end result—total emancipation—was more a matter of military necessity than moral progress.

Our greatest president, assessing the contribution of black soldiers in 1864, understood this:

We can not spare the hundred and forty or fifty thousand now serving us as soldiers, seamen, and laborers. This is not a question of sentiment or taste, but one of physical force which may be measured and estimated as horse-power and steam-power are measured and estimated. Keep it and you can save the Union. Throw it away, and the Union goes with it.

The United States of America did not save black people; black people saved the United States of America. With that task complete, our "ally" proceeded to repay its debt to its black citizens by pretending they did not exist. In 1875, Mississippi's provisional governor, Adelbert Ames, watched as the majority-black state's nascent democracy "progressed" from terrorism to anarchy and then apartheid. Taking in regular reports of blacks being murdered, whipped, and intimidated by the Ku Klux Klan, Ames wrote the administration of President Ulysses Grant begging for aid. The Grant Administration declined:

The whole public are tired of these autumnal outbreaks in the South, and the great majority are ready now to condemn any interference on the part of the government.

A horrified and exasperated Ames told his wife that blacks in Mississippi

... are to be returned to a condition of serfdom—an era of second slavery .... The nation should have acted but it was “tired of the annual autumnal outbreaks in the South” .... The political death of the negro will forever release the nation from the weariness from such “political outbreaks.” You may think I exaggerate. Time will show you how accurate my statements are.

Ames was totally accurate. For the next century, the United States legitimized the overthrow of legal governments, the reduction of black people to forced laborers, and the complete alienation—at gunpoint—of black people in the South from the sphere of politics.

Chait's citation of the end of lynching as evidence of America serving as an "ally" is especially bizarre. The United States never passed anti-lynching legislation, a disgrace so great that it compelled the Senate to apologize—in 2005.

"There may be no other injustice in American history," said Louisiana Senator Mary Landrieu, "for which the Senate so uniquely bears responsibility." Even then, a half century after Emmett Till's murder, the sitting senators from Mississippi—the state with the most lynchings—declined to endorse the apology.

"You don't stick a knife in a man's back nine inches," said Malcolm X, "and then pull it out six inches and say you're making progress."

The notion that black America's long bloody journey was accomplished through frequent alliance with the United States is an assailant's-eye view of history. It takes no note of the fact that in 1860, most of this country's exports were derived from the forced labor of the people it was "allied" with. It takes no note of this country electing senators who, on the Senate floor, openly advocated domestic terrorism. It takes no note of what it means for a country to tolerate the majority of the people living in a state like Mississippi being denied the right to vote. It takes no note of what it means to exclude black people from the housing programs, from the GI Bills, that built the American middle class. Effectively it takes no serious note of African-American history, and thus no serious note of American history.

You see this in Chait's belief that he lives in a country "whose soaring ideals sat uncomfortably aside an often cruel reality." No. Those soaring ideals don't sit uncomfortably aside the reality but comfortably on top of it. The "cruel reality" made the "soaring ideals" possible.

From Daniel Walker Howe's Pulitzer Prize-winning What God Hath Wrought:

By giving the United States its leading export staple, the workers in the cotton fields enabled the country not only to buy manufactured goods from Europe but also to pay interest on its foreign debt and continue to import more capital to invest in transportation and industry. Much of Atlantic civilization in the nineteenth century was built on the back of the enslaved field hand.

From Edmund Morgan's foundational American Slavery, American Freedom:

In the republican way of thinking as Americans inherited it from England, slavery occupied a critical, if ambiguous, position: it was the primary evil that men sought to avoid for society as a whole by curbing monarchs and establishing republics. But it was also the solution to one of society’s most serious problems, the problem of the poor. Virginians could outdo English republicans as well as New England ones, partly because they had solved the problem: they had achieved a society in which most of the poor were enslaved.

White supremacy does not contradict American democracy—it birthed it, nurtured it, and financed it. That is our heritage. It was reinforced during 250 years of bondage. It was further reinforced during another century of Jim Crow. It was reinforced again when progressives erected an entire welfare state on the basis of black exclusion. It was reinforced again when the intellectual progeny of the same people who excluded black women from welfare turned around and inveighed against it through caricaturization of black women.

Jonathan Chait is arguably the sharpest political writer of his generation. If even he subscribes to a sophomoric feel-good rendering of his country's past, what does that say about the broader American imagination?

And none of this is even new:

The record is there for all to read. It resounds all over the world. It might as well be written in the sky. One wishes that–Americans—white Americans—would read, for their own sakes, this record and stop defending themselves against it. Only then will they be enabled to change their lives. The fact that they have not yet been able to do this—to face their history to change their lives—hideously menaces this country. Indeed, it menaces the entire world.

James Baldwin was not being cute here. If you can not bring yourself to grapple with that which literally built your capitol, then you are not truly grappling with your country. And if you are not truly grappling with your country, then your beliefs in its role in the greater world (exporter of democracy, for instance) are built on sand. Confronting the black experience means confronting the limits of America, and perhaps, humanity itself. That is the confrontation that graduates us out of the ranks of national cheerleading and into the school of hard students.

Chait thinks this view is "fatalistic." I think God is fatalistic. In the end, we all die. As do most societies. As do most states. As do most planets. If America is fatally flawed, if white supremacy does truly dog us until we are no more, all that means is that we were unexceptional, that we were not favored by God, that we were flawed—as are all things conceived by mortal man.

I find great peace in that. And I find great meaning in this struggle that was gifted to me by my people, that was gifted to me by culture.