Shared posts

Stop Drawing Dead Fish

Extra Credits Season 6, Ep. 8: Like a Ninja

Come discuss this topic in the forums!

How one EVE Online player nearly crashed the market with a single useless item

Dan Kaminsky on Bitcoin

Quotes from Silk Road's anonymous founder

Colorphobia, Matheus Lopes - - - Follow Matheus Lopes on...

Karen McGrane on Content: WYSIWTF

Arguing for “separation of content from presentation” implies a neat division between the two. The reality, of course, is that content and form, structure and style, can never be fully separated. Anyone who’s ever written a document and played around to see the impact of different fonts, heading weights, and whitespace on the way the writing flows knows this is true. Anyone who’s ever squinted at HTML code, trying to parse text from tags, knows it too.

On one hand, the division of labor between writing and presentation can be seen at every point in our history. Ancient scribes chiseling stone tablets, medieval monks copying illuminated manuscripts, printers placing movable type—we’ve never assumed that the person who produces the document and the person who comes up with the ideas must be one and the same.

And yet, we know that medium and message are intertwined so tightly, they can’t be easily split apart. Graphic designers rail against the notion that “look and feel” can be painted on at the end of the process, because design influences meaning. The more skilled we are as communicators, the more we realize that the separation of content from presentation is an industrial-age feint, an attempt to standardize and segment tasks that are deeply connected.

Today, we try to enforce the separation of content and form because it’s good for the web. It’s what makes web standards possible. It enables social sharing and flexible reuse of content. It supports accessibility. It’s what will keep us sane as we try to get content onto hundreds of new devices and form factors.

When talking about how best to separate content from presentation, designers and developers tend to focus on front-end code—which makes sense, because that’s what we have the most control over. But, as with so many challenges we have with content on the web, the real issue lies in the tools we give content creators to help them structure, manage, and publish their content. The form that content takes depends as much on CMS as it does on CSS.

How should content management tools guide content creators to focus on meaning and structure? What’s the right amount of control over presentation and styling in the CMS? And how should these tools evolve as we break out of the web page metaphor and publish content flexibly to multiple platforms? Let’s look at three tools that sit at the intersection of content and form.

Preview button

Even the most die-hard structured content editors still like seeing what their work is going to look like. Writers print out documents for editing to give them a different view from what they see on the screen. Bloggers instinctively hit the preview button to look at their work the way a user will see it.

Whoops. Decades of work refining the emulators between desktop publishing programs and laser printers means that writers can feel confident that their document will look virtually identical, regardless of where it’s printed. We’ve carried that assumption over to the web, where it’s categorically untrue. Different browsers render content in their own vexingly special way. Users can change the font size—even add their own custom style sheet. Today, the same document will render differently on desktops, tablets, and mobile devices. The preview button is a lie.

Yet we can’t just throw the baby out with the bathwater. In fact, seeing content in context becomes even more important as our content now lives across devices and platforms. Instead of throwing up our hands and saying “preview is broken,” it’s time to invent a better preview button.

One publishing company I know of has built its own custom preview rendering interface, which shows content producers an example of how each story will appear on the desktop web, the mobile web, and an app. Is it perfect? Far from it. Content will appear in many more contexts than just those three. Is it better than nothing? Absolutely.

WYSIWYG

The desktop publishing revolution ushered in by the Macintosh allowed the user to see a document on screen in a form that closely mirrored the printed version. The toolbar at the top of the screen enabled the user to add formatting—change the font, insert an image, add typographic effects like headings and bullets, and much more.

In an effort to carry over this ease of use to the web, we allow content creators to embed layout and styling information directly into their content. Unfortunately, the code added by content creators can be at odds with the style sheet, and it’s difficult for developers to parse what’s style and what’s substance. When it comes time to put that content on other platforms, we wind up with a muddled mess.

What is the right amount of formatting control to give content creators? That’s a difficult question to answer, because it pierces right to the heart of what’s stylistic and what’s semantic. Even something as simple as adding bold and italic text forces us to ask if we’re really just styling the text, or adding semantic meaning (say, a book title or a warning message.)

Better content modeling can solve some of these problems, encouraging content creators to appropriately “chunk” their text. By banishing blobs of text with formatting embedded and replacing them with chunks of clean, presentation-independent content, we’re building in the distinction between content and form right from the start.

But imagining that each “chunk” of content is a field in the database (with its own input field) rapidly devolves into the absurd. That way lies madness. The real solution isn’t necessarily to “banish blobs,” but to replace the WYSIWYG toolbar with semantic markup. Rather than entering all text into discrete fields, content authors wrap text that describes what it is. Our book title doesn’t need to be a separate field if we can wrap it in the proper tags.

Defining what goes in a field and what goes in a tag requires a tighter collaboration between content authors, CMS architects, and front-end developers. It’s time we started having these conversations.

Inline editing

We’re evolving. Not satisfied to rely just on tools that are vestiges of the desktop publishing era, we’re developing new and innovative ways to mix up content and formatting that are unique to the way the web works. There’s no better example of this than inline editing.

Inline editing allows content creators to directly manipulate content in the interface, with no separation between the editing screen and the display. Medium offers an editing interface that’s identical to the desktop display and in-place editing is being added to Drupal 8 core.

One of the questions I get asked most frequently is “how can I get my content creators to understand why it’s so important to add structure and metadata to their content?” This, I believe, is one of the fundamental challenges we’re facing on the web, particularly as we adapt to a multi-channel future. Inline editing encourages content creators to focus on the visual presentation of the desktop interface. Just at the moment when we need content creators to think about the underlying structure, we’re investing in tools that obscure the “connective tissue.”

Jeff Eaton sums up this problem nicely in a post called Inline Editing and the Cost of Leaky Abstractions:

The editing interfaces we offer to users send them important messages, whether we intend it or not. They are affordances, like knobs on doors and buttons on telephones. If the primary editing interface we present is also the visual design seen by site visitors, we are saying: “This page is what you manage! The things you see on it are the true form of your content.”

The best solution isn’t to build tools that hide that complexity from the user, that make them think that the styling they’re adding to the desktop site is the “real” version of the content. Instead, our goal should be to communicate the appropriate complexity of the interface, and help guide users to add the right structure and styling.

The era of “desktop publishing” is over. Same goes for the era where we privilege the desktop web interface above all others. The tools we create to manage our content are vestiges of the desktop publishing revolution, where we tried to enable as much direct manipulation of content as possible. In a world where we have infinite possible outputs for our content, it’s time to move beyond tools that rely on visual styling to convey semantic meaning. If we want true separation of content from form, it has to start in the CMS.

Principles of Writing Consistent, Idiomatic JavaScript

If you’re looking for a thorough JavaScript style guide for your team, Rick Waldron’s Principles of Writing Consistent, Idiomatic JavaScript is a great place to start.

Secret Metafilter

Secret Metafilter scrapes the past month's worth of Metafilter posts and shows recent comments (made in the past 4 days) on posts that are between a week and a month old.

More information is available on the about page.

The code running the site is available on github: https://github.com/wiseman/secretmetafilter

[Link]

The Case For (Almost) Monopolies

Oligopolies are situations where a market consists of only a few firms. We dislike them. Think of the cellular service industry, where AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, and Sprint control over three-quarters of the market. We roundly abuse our cellular carriers, and assume the lack of competitors is to blame for our dropped calls and prison-like cell phone plans.

It is standard economic theory that competition benefits consumers and society. Without competitors, monopolists can rest on their haunches, reaping profit without improving their products and services. But companies in a competitive industry will constantly seek to improve their offerings in search of greater profits and market share. The improvements and innovations of any one company will force the others to adapt or risk falling behind.

As Stanford business professor Bill Barnett points out, competition between the makers of cell phones is how phones went from this:

to this:

We dislike oligopolies because we assume that more competition is always better. But a 2008 study (pdf) on how the number of competitors affects competition found the exact opposite.

In the study, researchers looked at the results of standardized tests like the SAT in test centers with varying number of test takers. They found that students scored higher when there were less students taking the test with them. Students in massive testing centers with hundreds of fellow test-takers scored lower. The researchers also replicated the results in a controlled setting.

Why do you score higher on tests when there are less people around? The researchers noted that the “motivation to compete is mediated by social comparison.” Competing against a huge group is less motivating than competing with a few individuals because it’s harder to compare yourself to your competition.

The study concludes that increased competition, in terms of the number of competitors, actually reduces competition and its benefits.

Although this study was done with individuals, it would make sense for it to apply to companies. It will be much more essential to respond to an innovation made by one of your 4 competitors than one of 10,000 competing companies. And in an oligopoly, it will be much easier for executives to compare themselves to their competition. Clarity over which company is number 1, 2, 3, and 4 can fuel the competitive spirit in a way that competing to be a better convenience store - among the tens of thousands that aren’t easily compared - simply cannot.

So maybe oligopolies have gotten a bad rap. This study suggests that a market being dominated by a handful of companies could actually be good for competition and innovation. If our cell phone service is bad, maybe something other than the small number of providers is to blame.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.

How Would You Save Journalism?

Newspapers and magazines are in trouble. We think they will mostly die, because we think we know what will replace them, and it is too far from their current model for them to reach it in time.

And yet people still need at least some of what they do.

- Paul Graham, Request for Startups 1: The Future of Journalism

The journalism industry seems to be in trouble. Newspaper revenue has shrunk from $57.4 billion in 2003 to $38.6 billion in 2012. All of their traditional sources of revenue are falling. Magazine circulation is down sharply. Publishers have laid off their staff en masse or shut down entirely. It is harder than ever to make a living as a journalist.

Let’s rehash what has already been said ad nauseum: the Internet killed the business model that previously funded journalism. Newspapers, for example, used to collect subscription fees to deliver a physical product. They also earned good advertising revenues because companies had few options for advertising their products. This was especially true for local advertisers posting in the classified section of newspapers. With the Internet, however, distribution became free, places to advertise became plentiful, and “local” became an abstraction.

If the incumbents of journalism are dying, what will replace them? Or, more precisely, what new business model for journalism will emerge if the old one is dead?

Online advertising has not, thus far, proven to be the savior of online journalism. Since the supply of websites that businesses can advertise on is so plentiful, the revenue per advertising impression is tiny. Online ads are simply not bringing in enough revenue to sustain news outlets. Print advertising dollars are being replaced by digital advertising cents:

Because these online ads generate so little money per pageview, you need a lot of pageviews to run a business. This sets up up strong incentives to grow pageviews through annoying slide shows, misleading headlines, and recycling other people’s original content. Publishers are competing hard to get the most pageviews, and so far, that hasn’t proven to be a good way to fund original content and reporting.

For the last two decades, the conversation has been about “how do you save newspapers.” Now the conversation is starting to center around what replaces newspapers to save journalism. Investor Paul Graham has challenged startups to invent a new business model for journalists that supports great writing rather than link baiting and slideshows:

What would a content site look like if you started from how to make money—as print media once did—instead of taking a particular form of journalism as a given and treating how to make money from it as an afterthought?

In this post, we look at some of the experiments taking place today to fund high quality content. We hope it can be a starting point for people to discuss how they would save journalism. That’s probably what’s needed to save journalism, brainstorming new ideas and then trying them.

In that spirit, this post ends with an experiment that you can participate in. The proceeds of the experiment will go to charity, but it’s a small test of whether people are willing to pay for content.

So, what do people talk about when they talk about a business model for journalism?

Paywall

The most commonly discussed business model to save journalism is a subscription paywall. Subscribers pay a monthly fee to publishers for access to their content. The upside of this approach is that readers directly fund the journalism. Whereas advertisers don’t really care about funding high quality investigative reporting on inner-city schools, subscribers might.

The most commonly discussed business model to save journalism is a subscription paywall. Subscribers pay a monthly fee to publishers for access to their content. The upside of this approach is that readers directly fund the journalism. Whereas advertisers don’t really care about funding high quality investigative reporting on inner-city schools, subscribers might.

Paywalls that keep non-subscribers from accessing content can be rigid (you must pay to see anything) or porous (you can see a lot, but not all, of the content for free). There have been a few flagship examples of paywalls working to some degree. The New York Times and Wall Street Journal have paywalls, but they are the leading newspapers in the world. Even if paywalls work for them, would it work for the 3rd best newspaper? What about the 10th best paper? What about a one person blog? So far the evidence strongly suggest no.

Take the example of Newsday, a Long Island newspaper that was purchased in 2009 for $650 million. Under the new ownership, the website was put under a paywall. After 3 months, Newsday only managed to get 35 subscribers for its online content. Redesigning the website for subscriptions cost $4 million and only generated $9,000 in revenue. Ouch.

These paywalls lead to some perverse consumer behavior. People show boundless creativity to get around paywalls. Even readers that can easily afford a New York Times subscription confess to jumping the paywall by opening new browsers, Googling the articles, and borrowing friends’ passwords.

By limiting distribution, paywalls also hinder outlets’ ability to find new readers. Felix Salmon of Reuters comments:

But there’s another consideration, too: the more formidable the paywall, the more money you might generate in the short term, but the less likely it is that new readers are going to discover your content and want to subscribe to you in the future.

Several startups have recently used subscriptions to fund journalism with some success. Marco Arment’s The Magazine, a fortnightly iOS magazine, costs $2 a month. Andrew Sullivan’s The Dish costs about the same amount. Sullivan’s experiment has generated over $600,000 in revenue and he’s very transparent with his readers about the financial performance of his site.

An interesting aspect of both The Magazine and The Dish is that neither seems to take something away from the reader (unlike, say, The Wall Street Journal’s paywall). Most readers of the The Dish will never hit the paywall, but many of them decide to subscribe on a voluntary basis. 29% of the the people that subscribe to The Dish have never even logged in to claim their subscriber benefits. Moreover, The Magazine never existed without a paywall, so readers never felt like content was taken away form them.

Micropayments

Micropayments have been bandied about as a means to save journalism since the advent of the web. The premise is that a good piece of writing has some economic value, but it might only be about a penny or a dime per view. Walter Isaacson summarizes it well:

The key for attracting online revenue, I think, is coming up with an iTunes-easy, quick micropayment method. We need something like digital coins or an E-Z Pass digital wallet – a one-click system that will permit impulse purchases of a newspaper, magazine, article, blog, application, or video for a penny, nickel, dime, or whatever the creator chooses to charge.

Clay Shirky presents the other side of the argument, contending that micropayments won’t work:

This strategy doesn’t work, because the act of buying anything, even if the price is very small, creates what Nick Szabo calls mental transaction costs, the energy required to decide whether something is worth buying or not, regardless of price.

Google and Paypal introduced some micropayment offerings for publishers, but Shirky’s argument is that no one is going to stop their flow of reading articles to pay for one by Google Wallet. The friction is too high.

So, is the key to saving content building a micropayments system that’s completely frictionless? Maybe, but Shirky’s argument goes further. Micropayments don’t solve any problems for users. They hypothetically solve problems for publishers, which is why newspapers and publishers keep talking about them. But readers are not clamoring to pay nickels and dimes for articles. Moreover, for most articles, good free substitutes are available online. So the article would have to be extraordinarily unique for a user to cough up even a penny.

To our knowledge, no journalistic organization or content startup has funded its writing through micropayments. Even Google’s micropayment service seems to be shuttered. Despite many attempted technology solutions to facilitate micropayments, no publishers seems to have found a way to make it work.

Under what circumstances would micropayments work? The friction of purchasing content would need to be near zero - as easy and unnoticeable as purchasing electricity. The content would need to be unique and not easily “substitutable.” And finally, to borrow from the lesson of Andrew Sullivan’s website, it might help if users felt like they were volunteering the payment instead of being scolded into it.

Subsidy Model 2.0: Content as Lead Generation for More Profitable Things

The expense of printing created an environment where Wal-Mart was willing to subsidize the Baghdad bureau. This wasn’t because of any deep link between advertising and reporting, nor was it about any real desire on the part of Wal-Mart to have their marketing budget go to international correspondents. It was just an accident. Advertisers had little choice other than to have their money used that way, since they didn’t really have any other vehicle for display ads.

- Clay Shirky, Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable

Some of the most successful blogs make their money in ways not directly related to their writing. For example, TechCrunch and All Things Digital put on very successful (and profitable) tech conferences. Some personal blogs generate leads for a profitable consulting business or training course.

This is a profitable way to fund original content, but the writing is still subsidized by something else. The writing is what builds the brand that allows the publisher to cash in on other revenue sources. So it’s a symbiotic relationship, but still a relationship where reporting is being subsidized.

Other content companies use the web to generate leads to sell their content in other forms. The Oatmeal, a most excellent webcomic, has a free website. You can, however, purchase comics on prints and t-shirts or in print books (that also have original comics). The vast majority of users read the digital comics for free and some of them purchase that content in other forms. This is a common business model among people debating the economics of writing content for a living. They publish free articles online as lead generation for books.

Pay What You Want

In 2007, Radiohead released their album In Rainbows online and let fans choose what to pay for the album. It was a solid success, but this was freakin’ Radiohead. Can it work elsewhere? After all, Radiohead hasn’t even used its pioneering model on subsequent albums. However, we are seeing this this model of fans paying what they want applied to other forms of content.

Humble Bundle, for example, let’s fans choose to pay what they want for indie video games. But the gamers also decide what portion of the purchase price should go to charity and what portion to Humble Bundle as a tip. It’s a purely voluntary business model. Bundles of video games frequently generate millions of dollars in sales. The company even did a bundle of e-books that generated $1.2 million in voluntary sales.

Would this work if video game giant Electronic Arts put on a similar “pay what you want” promotion with their games? There is some evidence that pay what you want models only work with some charitable component or cause like supporting independent developers.

In 2010 Berkeley researchers performed an experiment selling souvenir photos to people after they rode a roller coaster. They tried 4 different pricing schemes. The first was a flat fee of $12.95 for the photo. The second was a flat fee of $12.95 for the photo, but half the money went to charity. The third was to pay what you want for the photo. The final scheme was to pay what you want for the photo, with half the money going to charity.

Allowing people to name their own price was a complete disaster. Everyone lowballed the researchers. But when customers paid what they wanted and half the money went to charity, the researchers raked in money. It generated 3X more revenue per rider than any other option. Adding a charity component to the flat fee had basically no effect on whether someone would buy it.

When people can pay what they want, this experiments indicates it helps if there is a worthy cause attached to it. In that case, it works well. Otherwise, customers will choose to pay almost nothing.

“Pay what you want” has also been reincarnated on Kickstarter. Yes, tangibly you get prizes for donating. But there is also the feeling of connecting with the campaign creator and being part of a cause. Felix Salmon of Reuters comments on how a pay what you want model responds to netizens aversion to paying for content:

On the internet, people prefer carrots to sticks. That’s one of the lessons of Kickstarter, too. To put it in Palmer’s [a prominent Kickstarter campaigner] terms: if you want to give money, you’re likely to give more, and to give more happily, than if you feel that you’re being forced to spend money.

The “pay what you want” business model is purely voluntary. The amount a user can give is uncapped. Most people will give nothing or very little, but passionate fans can give a lot if they want. Even successful paywalls like Andrew Sullivan’s at The Dish can be viewed through the “use carrots not sticks” lens. Most of his supporters aren’t hitting paywalls and many of the suscribers never even log in. Are they really buying access to content or are they supporting a cause and journalist they care about?

How could you use carrots and not sticks to fund content? Let’s do a quick experiment.

An Experiment: Decide what we write about on our blog and support charity

We get a lot of emails at Priceonomics from readers with suggestions about topics they’d like for us to write about on the blog. We love getting the suggestions, but we never have enough time to properly research them.

So, here’s a test: if you make a donation to charity, you can dictate what we write about next.

Send us any amount of money (which we’ll donate to charity) and you can vote to decide on the topic of our next blog post. If there has ever been a topic that you thought, “I wish someone would spend 50 hours researching this and then write a story or report about it,” now is your chance.

Send us a dime, a dollar, a thousand dollars… whatever you want by Paypal or Bitcoin. If you donate more money, you’ll get slightly more votes on choosing the next blog post. So be generous! We’ll donate all of the proceeds to charity (EFF, Pro Publica & Watsi). Apologies in advance that both Paypal and Bitcoin are not easy to use.

Click the above button or use this link to donate by Paypal

Donate by Bitcoin: 1AxzBwU2FygXmW3WNHZHkGdFFTVHX3P68u

Send us your blog post suggestions on Paypal (or by email) and then we’ll aggregate the suggestions and follow up with you by email to vote and choose the winner of the next blog post. We’ll update the results below.

Number of Donors: 15

Total Amount Raised for Charity: $180.22

Average Amount: $12.01

Most Generous Donation: $50

Conclusion

“If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?” The answer is: Nothing will work, but everything might. Now is the time for experiments, lots and lots of experiments…

- Clay Shirky, Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable

Over the last two decades, the Internet thoroughly crushed newspapers and magazines. These organizations might survive, or they might not. Regardless of their survival, what will be the business model that funds journalism?

It’s entirely possible that journalism could see a new business model emerge. The old model required fixed payments from subscribers and advertisers that went to corporations (who then employ journalists). The new model could be completely different. It could rely on a small but loyal group of patrons that voluntarily give money to people or causes that they care about. Or the new model could be something else entirely. Or. journalism could die.

But that seems unlikely. The interest in good content is still strong. How much time do we spend perusing fascinating content on Twitter, Reddit or Hacker News? There is great content out there; if it’s paired with the right business model, there could be a resurgence in original reporting. Online, the barriers to entry for journalism are low. It’s never been easier or cheaper to run an experiment on funding journalism, and it seems as if journalists and startups are trying to solve this problem. To save content, you need to try to save content.

What do you think? What will be the business model that saves journalism? Compulsory payments? Donations? Subscriptions? Micropayments? More ads? Pay what you want? Nothing?

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter here or Google. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.

Here’s the link to make a donation to charity and tell us what to write about next on the blog.

Introducing Trello Business Class!

Trello is used by thousands of businesses every day. As Trello becomes an essential tool in these organizations, you’ve asked for more power over your boards and data. Today we are enabling that extra control with the launch of Trello Business Class.

What’s in the box? All the power of a Trello organization plus extra features like Google Apps integration, extra administrative controls for boards and members, one-click bulk data export, and a new, view-only observer role. All for $25 per month or $200 per year per organization. It doesn’t matter if you’ve got 5 members or 50, 10 boards or 200. It’s a simple and affordable price.

Go upgrade your organization to Business Class now!

Or check out some of the features first…

Google Apps integration

With Business Class, you can connect your Trello organization to your business’s Google Apps account. On the Members page, you’ll see who in your organization has an account. If they aren’t in the organization yet, you will be able to add them with a single click. Since there are no member limits, you never have to worry about paying more for each new member.

Administrative controls

Business Class gives administrators more control over your organization. A few of the features include…

- Choose which email domains can be invited to your organization. For example, if you only want Trello users with a fogcreek.com email address to join your organization, you can configure that on your “Organization Settings” page.

- You are also able to restrict board visibility, so that, for example, you can prohibit the creation of public or private boards in your org.

- As an organization admin, you are able to see and edit all organization boards, even if you are not on the board. You are also be able to see all private boards in your organization.

Bulk data export

We’ll bundle all of your organization data and make it available with just one click. You can choose to include attachments or just have a link to them. The data will be in JSON format with the attachments in their native format.

Observers

Observers are board members that can view the board, vote, and comment, but are not able to edit, move, or create cards. The addition of observers lets you share private organization boards without sacrificing control. It’s ideal for freelancers or contractors that don’t need or shouldn’t have full control of the board.

Better member control and visibility

With the new Members page, you get more insight into member activity. You are able to see when a member was last active in the organization and which boards they are on. You are able to see what organization cards they are assigned to.

You also have the ability to deactivate members. This means they will lose access to boards in the organization, but other organization members will still see the members in a faded state on their boards and cards. This is useful for divvying up tasks after a member leaves an organization.

Trello is still free. As before and as always, you still have access to unlimited boards and organizations with an unlimited number of members with your free Trello account, with or without Business Class. Business Class provides organizations the extra administrative control they need at a simple and reasonable price.

Okay, that’s just about everything! Now go upgrade your organization!

Be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Google+, and let us know what you think!

Richard Prince wins "fair use" appeal

Q: Do you have those earrings just for fun or do they serve a purpose?

Morgan Freeman: Yeah these earrings are worth just enough to buy me a coffin if I die in a strange place. That was the reason why sailors used to wear them.

What A 16th Century British Currency Can Teach Journalism

News outlets are struggling. They are earning less revenue from ads and steadily losing readers and viewers.

As more people turn online to get their news, it’s a common assumption that news outlets need to adapt to the new ways of consuming news. The extent to which The New York Times and CNN, the thinking goes, adjust to the pace of breaking news over social media and the 24 hour news cycle, will determine whether they survive.

But this thinking may have it all wrong. A look at the problems Britain experienced with its currency in the 16th century suggests why.

A post from Foreign Policy explains how British currency began losing its value due to sloppy coinage practices. In response, a wealthy merchant suggested that Queen Elizabeth I mint new coins, distinct from the old coins but more trustworthy.

But no one used the new coins. The problem was that the old and new coins had different values, but equal power as legal tender:

“If coins containing metal of different value enjoy equal legal-tender power, then the ‘cheapest’ ones will be used for payment, the better ones will tend to disappear from circulation.”

This resulted in the maxim that “Bad money drives out good.”

As the article points out, this is equally applicable to breaking news stories.

During the search for the Boston Marathon bombers, people shared false news on social media. This included incorrect reports of an early arrest of the bomber (it was actually an innocent Saudi man questioned out of pure prejudice) to false accusations of the bombers’ identities based on an attempt to crowdsource the investigation on Reddit. This did not just consist of individuals on Twitter sharing false news. In their rush to match the pace of speculation on social media, outlets like CNN misreported breaks in the story.

In other words, bad news drove out the good.

So what should news outlets do? Maybe they should stop trying to compete. Blogs and other sources willing to “report” news without verification or a thought to the consequences will always beat CNN and The New York Times when it comes to pleasing people seeking a shot of dopamine every minute in the form of an update - no matter how inaccurate or poorly presented.

Instead, news outlets need to differentiate by focusing on presenting news cohesively and in a trustworthy manner. Despite the avalanche of Boston coverage, this author, a Massachusetts native, found himself wishing for more summaries of the events from a trusted source - rather than minute to minute updates that assumed a knowledge of every prior break in the story.

Trust is the biggest factor setting traditional news outlets apart from other online sources. Social media is a key way to distribute news. But maybe news outlets don’t need to hire peppy young kids to compensate for crusty old journalists’ lack of social media savvy. Instead, maybe they need to double down on reporting, slowly and carefully, with the solemn and trusted gravitas of Walter Cronkite.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.

Why Publishers Love Twitter & Not Facebook

Facebook sends a lot more traffic to the Priceonomics Blog than Twitter does. Yet whenever we hit “publish” on a post, we immediately check Twitter to see how the article is doing. Why? Because Twitter makes it easy to see if people are sharing your articles and Facebook makes it impossible.

Seeing someone share your blog post is like a tiny shot of dopamine for an author. That’s basically the immediate payoff from publishing something. Twitter gives you that dopamine readily. Facebook makes it impossible to see how your article is being shared.

So, even though Facebook is a huge source of traffic compared to Twitter, we suspect that most online authors, like us, spend more time glued to Twitter. Is anyone sharing our article? Do people like us? Do people hate us? Will we be invited to prom? Only Twitter holds the answer.

Here’s an example of a recent blog post we published about the band Phish. The post had approximately 79 thousand views, most of them in the first two days.

Of those 79 thousand visitors, approximately 18,000 people shared it on Facebook and 5,000 people shared it on Twitter.

This resulted in 39,000 thousand visits from Facebook compared to only 2,000 from Twitter. Also note, most of the traffic from Hacker News shows up as direct for some reason in our Google Analytics.

So, based on the traffic alone, you’d think Facebook is 20 times more important than Twitter for an online publisher, right? You’d spend all your time analyzing who’s sharing it on Facebook, what people are saying, and the exact mechanism by which it’s going viral. But you can’t.

Here’s what happens when you try doing a search for Priceonomics on Facebook in their new open graph search. There is no way to find the articles by Priceonomics that Pages and people are publically sharing (and if there is a way, someone let us know because it’s not easy to find).

Try refining the search a bit to find our article about Phish and Facebook suggests you do a Bing web search! If that’s not a slap in the face, what is?

On the other hand, go to Twitter and search for “priceonomics phish” and it’s actually useful from a publisher’s standpoint. You can see who’s sharing it and what people are saying about it. As an author, your reason for existence is vindicated!

We’d imagine that when writers at TechCrunch, Wired, or the New York Times publish something, they immediately monitor it on Twitter rather than Facebook, even though Twitter is a smaller source of traffic. That probably gives Twitter mindshare with publishers and the media far in excess of its actual ability to deliver traffic.

A lot of Facebook sharing is private by default. But clearly Facebook has aspirations to take on Twitter in the public sharing arena. If they do, they may want to make it dead simple for publishers to see how people publicly are sharing content on Facebook. Till then, it’s not surprising that all the public conversations about ideas and events take place on Twitter, not Facebook.

Twitter gives publishers a rush of happiness, and Facebook gives them a Bing search. What did you think would happen?

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter here or Google. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.

A shocking (and hot!) tip for preserving produce

By W. WAYT GIBBS

Associated Press

Nothing is more frustrating than finding the perfect cucumber or head of lettuce at the farmers market, paying top-dollar for it, and then… tossing it out a week later when it has gone moldy or slimy in the refrigerator.

No doubt one reason so many of us eat too many convenience foods and too few fruits and vegetables is that it can be hard to get our busy schedules in sync with the produce we bring home with the best of intentions.

Food scientists, however, have discovered a remarkably effective way to extend the life of fresh-cut fruits and vegetables by days or even a week. It doesn’t involve the chlorine solutions, irradiation or peroxide baths sometimes used by produce packagers. And it’s easily done in any home by anyone.

This method, called heat-shocking, is 100 percent organic and uses just one ingredient that every cook has handy – hot water.

You may already be familiar with a related technique called blanching, a cooking method in which food is briefly dunked in boiling or very hot water. Blanching can extend the shelf life of broccoli and other plant foods, and it effectively reduces contamination by germs on the surface of the food. But blanching usually ruptures the cell walls of plants, causing color and nutrients to leach out. It also robs delicate produce of its raw taste.

Heat-shocking works differently. When the water is warm but not scalding – temperatures ranging from 105 F to 140 F (about 40 C to 60 C) work well for most fruits and vegetables – a brief plunge won’t rupture the cells. Rather, the right amount of heat alters the biochemistry of the tissue in ways that, for many kinds of produce, firm the flesh, delay browning and fading, slow wilting, and increase mold resistance.

A long list of scientific studies published during the past 15 years report success using heat-shocking to firm potatoes, tomatoes, carrots, and strawberries; to preserve the color of asparagus, broccoli, green beans, kiwi fruits, celery, and lettuce; to fend off overripe flavors in cantaloupe and other melons; and to generally add to the longevity of grapes, plums, bean sprouts and peaches, among others.

The optimum time and temperature combination for the quick dip seems to depend on many factors, but the procedure is quite simple. Just let the water run from your tap until it gets hot, then fill a large pot of water about two-thirds full, and use a thermometer to measure the temperature. It will probably be between 105 F and 140 F; if not, a few minutes on the stove should do the trick. Submerge the produce and hold it there for several minutes (the hotter the water, the less time is needed), then drain, dry and refrigerate as you normally would.

Researchers still are working out the details of how heat-shocking works, but it appears to change the food in several ways at once. Many of the fruits and vegetables you bring home from the store are still alive and respiring; the quick heat treatment tends to slow the rate at which they respire and produce ethylene, a gas that plays a crucial role in the ripening of many kinds of produce. In leafy greens, the shock of the hot water also seems to turn down production of enzymes that cause browning around wounded leaves, and to turn up the production of heat-shock proteins, which can have preservative effects.

For the home cook, the inner workings don’t really matter. The bottom line is that soaking your produce in hot water for a few minutes after you unpack it makes it cheaper and more nutritious because more fruits and veggies will end up in your family rather than in the trash.

___

HEAT-SHOCKING GUIDELINES

The optimal time and temperature for heat-shocking fruits and vegetables varies in response to many factors – in particular, whether they were already treated before purchase. Use these as general guidelines.

- Asparagus: 2 to 3 minutes at 131 F (55 C)

- Broccoli: 7 to 8 minutes at 117 F (47 C)

- Cantaloupe (whole): 60 minutes at 122 F (50 C)

- Celery: 90 seconds at 122 F (50 C)

- Grapes: 8 minutes at 113 F (45 C)

- Kiwi fruit: 15 to 20 minutes at 104 F (40 C)

- Lettuce: 1 to 2 minutes at 122 F (50 C)

- Oranges (whole): 40 to 45 minutes at 113 F (45 C)

- Peaches (whole): 40 minutes at 104 F (40 C)

___

Photo credit: AP Photo/Modernist Cuisine, LLC, Chris Hoover

A Stopping Problem

Let’s play the following game: you roll a four-sided die; if 1 or 2 come up, you get 1$; if 3 comes up, you lose 1$; if 4 comes up, the game ends, and you lose all of your gains; finally, you can stop the game at any point and keep your gains. How do you play so that you maximize your gains?

For practice, let’s find a strategy for a simpler game: the rules are the same, except that if 4 comes up, the game ends, but you don’t lose any gains. The rules are easier to reason about now: for any one round, there’s a 25% chance of losing 1$, a 50% chance of gaining 1$, and a 25% chance of the game ending. In other words, for any one round, you have an expected gain of \(25\% \times (-1\$) + 50\% \times 1\$ = 0.25\$\). So, a good strategy would simply be to play for as long as possible.

Back to our problem: it’s the same as above, but getting a 4 means losing everything. So, in order to make a profit, we must stop voluntarily. Since we still make an expected 0.25$ on each round, we still want to play for as long as possible. The probabilities of not getting a 4 tell us how long we can keep going: we get to the second round in \(3/4\) of the cases, to the third in \((3/4)^2\) of the cases, and so on.

| Round | Probability of reaching round |

|---|---|

| 2 | 75% |

| 3 | 56% |

| 4 | 42% |

| 5 | 32% |

| 6 | 23% |

| 7 | 18% |

| 8 | 13% |

| 9 | 10% |

The probability of our reaching the ninth round is only 10%; this means that if we play this game 1000 times, we’ll only get to the ninth round about 100 of those times; this isn’t likely to be a long game. Since we know the expected gain of each round, we expect to make \(0.25\$ * 8 = 2\$\) if we voluntarily stop after the eighth round. So, here’s our strategy: pick the risk you’re willing to take, figure out the expected payoff if you play for that many rounds, play the game until you reach that payoff, and then stop. In our case, if you can stomach a 90% risk of failure, you’re expecting to make 2$, so play the game until you make 2$, and stop.

Our problem is similar to optimal stopping problems. The most common example is probably the secretary problem, which seems hard, but has a deceivingly simple solution. The problem in its pure form reads:

Ask someone to take as many slips of paper as he pleases, and on each slip write a different positive number. The numbers may range from small fractions of 1 to a number the size of a googol (1 followed by a hundred 0s) or even larger. These slips are turned face down and shuffled over the top of a table. One at a time you turn the slips face up. The aim is to stop turning when you come to the number that you guess to be the largest of the series. You cannot go back and pick a previously turned slip. If you turn over all the slips, then of course you must pick the last one turned.

A variant of this game came up in Trial of the Clone, an interactive fiction by Zach Weinersmith, the difference being that the goal was to surpass a certain score, rather than just maximize it. In my case, I had to make 2 points, which I did early on, but kept playing not realizing just how lucky I must have been.

The W3C on Web Standards: Digital Publishing and the Web

Electronic books are on the rise everywhere. For some this threatens centuries-old traditions; for others it opens up new possibilities in the way we think about information exchange in general, and about books in particular. Hate it or love it: electronic books are with us to stay.

A press release issued by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project in December 2012 describes an upward trend in the consumption of electronic books. The trends are similar in the UK, China, Brazil, Japan, and other countries.

“…the number of Americans over age 16 reading eBooks rose in 2012 from 16 to 23 percent, while those reading printed books fell from 72 percent to 67. …the number of owners of either a tablet computer or e-book reading device such as a Kindle or Nook grew from 18% in late 2011 to 33% in late 2012. …in late 2012 19% of Americans ages 16 and older own e-book reading devices such as Kindles and Nooks, compared with 10% who owned such devices at the same time last year.”

What does this mean for web professionals? Electronic books represent a market that’s powered by core web technologies such as HTML, CSS, and SVG. When you use EPUB, one of the primary standards for electronic books, you are creating a packaged website or application. EPUB3 is at the bleeding edge of current web standards: it is based on HTML5, CSS2.1 with some CSS3 modules, SVG, OpenType, and WOFF. EPUB3’s embrace of scripting is sure to encourage the development of more interactivity, which is sought after in education materials and children’s books.

Recently W3C has been working more closely with digital publishers to find out what else the Open Web Platform must do to meet that industry’s needs.

One comment we’ve heard loud and clear is that people care deeply about centuries-old print traditions. For example, Japanese and Korean users have accepted that many websites display text horizontally, from left to right. While that may be ok for the web, when these users read a novel, they expect traditional layout: characters rendered vertically and from right to left. Japanese readers often find it more tiring to read a long text in any other way. To address these requirements, W3C is looking at the challenges that vertical layout poses for HTML, CSS, and other technologies; see for example CSS Writing Modes Module Level 3.

Requirement of Japanese Text Layout summarizes the typesetting traditions and resulting requirements for Japanese. These traditions should eventually be reproduced on the web as well as in electronic books. In June, W3C will hold a digital publishing workshop in Tokyo on the specific issues surrounding internationalization and electronic books.

We have also heard that the “page” paradigm—including notions of headers, footnotes, indexes, glossaries, and detailed tables of contents—is important when people read books of hundreds or thousands of pages. Web technology will need to reintegrate these UI elements smoothly; see for example the CSS Paged Media Module Level 3 (Joe Clark talked about paged media and the production of ebooks in 2010, and Nellie McKesson gave us an update in 2012). In September in Paris, W3C will hold a workshop on the creation of electronic books using web technologies. Note that both this and the Writing Modes Module are still drafts and need further work. That means now is the right time for the digital publishing community to have its voice heard!

In the realm of metadata, important to publishers, librarians, and archivists, the challenge is to agree on vocabulary (and there are many: Harvard’s reference to metadata standards is only the tip of the iceberg). Pearson Publishing recently launched the Open Linked Education Community Group to examine creating a curated subset of Wikipedia data that can be used for tagging educational content.

Here are a few other places to look for activity and convergence:

- People take notes in books and highlight text. Most ebook readers these days have built-in support for these features, but they are not widely deployed on the web.

- Today search engines tend to ignore electronic books; I expect that will not remain the case for long.

- “Offline mode” in web technology is still difficult to use if you try to access more than a single page of a site. Since an ebook is quite often a packaged website, ebook offline mode will need to improve to support browsing.

- ebooks business models are likely to drive new approaches to monetization, some of which may be found in native mobile environments but not yet on the web.

Although publishing has some specific requirements not common to the web generally, I think that the distinction between a website (or app) and an ebook will disappear with time. As I have written before, both will demand high-quality typography and layout, interactivity, linking, multimedia, offline access, annotations, metadata, and so on. Digital publishers’ interest in the Open Web Platform is a natural progression of their embrace of the early web.

The Human is a RESTful Client

There's plenty of great technical writeups and non-technical writeups on REST. In short, REST is one way to model and present your data to your users in a consistent, logical fashion that lends itself to being accessible humans, machines, and your own developers. (I don't know if I just called developers neither human nor machine, but let's go with it.)

There's a number of great technical reasons to move to an architecture like REST. In fact, there's a number of great reasons to implement SOAP, XML-RPC, or similar architecture on your app, the distinctions being less relevant for this post. But REST isn't just for API clients or web browsers: REST is for people, too.

Part of what REST does really well is help you to define the resources for your app. User, Post, Tag, Comment... all of these form the concept of a blog. By defining your structure this way, not only can you craft a machine-readable and machine-writeable interface for your site, but you can end up centering your UI around this, too. It's easy enough to scaffold your usual CRUD of an app: a barebones form to create a new Post, a page to show that Post, an index page to list Posts.

Humans understand this. I'd wager even your stereotypical I-don't-understand-computers Farmville player has a basic grasp on the basics of REST, even though they haven't the foggiest of what a "resource" is. They might not know how to do something upon first visit, but they know what resource they want to interact with. Posting a comment on a blog post? Look for the form labeled "New comment". Signing up for an account? Look for the "New account" button. As long as the resources are basic and intuitive — "create a new TransientSubscriberSubscriptionNode" might be slightly too complex, for example — humans are going to have a good chance at figuring out how to work with your objects.

This is all pretty straightforward, of course. A comment on a blog is simple enough that it's hard for anyone to get that wrong. The problem is when you bleed between objects or devise complex on-page ajax interactions. I have nothing but reckless intuition to back this up, but I'd bet that the majority of the most-confusing forms and interactions online stem from a failure to separate resources sufficiently, or a failure to properly define resources for your app (one resource doing the job instead of splitting things up into smaller pieces, for example).

Admin screens are a magnet for this. The noble idea is to have a few screens to manage as much data as possible, since we really care about efficiency and flexibility and productivity and other words ending in -y. This is where the minefield of checkboxes and radio buttons and dropdown filters come from when you're trying to graft one screen onto multiple interactions with resources that are sort of related but not exactly related. Yes, it can certainly work, but the more you drift from that simplistic, single-resource mindset, the harder it is to intuitively grasp what the hell's going on here. And sure, you can add help text and documentation and mouseovers and plenty more to explain how all these doohickeys interact with the data, but that just means you have a more complex screen that's harder to use and harder to get others to use. This doesn't even take into account the harder technical hurdles you face with complex screens, either.

It's not just admin screens, of course. Complex, multi-page signup forms may expand beyond just the User object and into other areas (Profile, Social Networks, Preferences, Billing, and so on). There may be a tendency to have a listing page that offers inline editing, state changes, and child creation for each object on the page. The listing page may, in fact, list a mixture of four separate resources rather than having four discrete lists. By bypassing the simple and straightforward, the user has to sit and think about how they might go ahead and accomplish their goal. I don't know about you, but users aren't the brightest tool in the shed, so leaving them to their own devices to think for themselves probably will sink your company and likely will cause California to sink into the ocean.

I'm not saying any of these are wrong, of course. REST is meant to be broken, really. It's not entirely all-encompassing; we've all skimped on a show action when the data is small enough to put on the index action, or we've added a few actions to help separate out complex state changes. But every time you cram more interactions into your controller than those magic seven actions or try to consolidate multiple resources into one page, you're not just going against the REST implementation grain; you're going against what might be the most intuitive route for the user.

YMT Anatomy

The work of Syndey based visual artist YMT contains many anatomical elements inspired by personal experiences with medical problems since birth. Many of the elements also have a slight aboriginal feel to them and so much detail that you”ll want to stare at them for a while.

stickyembraces: I am rereading Rawls’ A Theory of Justice,...

I am rereading Rawls’ A Theory of Justice, which is always a pleasure. I suppose it was never released on Vulcan.

April 26, 2013

José Bruno BarbaroxaHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA

cahblr: Some time in the past three years, people have gotten it into their heads that Cards...

Some time in the past three years, people have gotten it into their heads that Cards Against Humanity is some sort of open-ended party game in which “there are no wrong answers” to the Black Cards. We feel terrible about the mistake. Here is the first in a two-part series devoted to revealing the correct answers to Cards Against Humanity.

What’s Teach for America using to inspire inner city students to succeed?

Idealistic white hipsters.

A romantic, candlelit dinner would be incomplete without _____.

Candles.

In Michael Jackson’s final moments, he thought about _____.

An itch on his lower back.

How am I maintaining my relationship status?

Responding attentively to my partner’s emotional needs.

What ended my last relationship?

Not responding attentively to my partner’s emotional needs.

In the new Disney Channel Original Movie, Hannah Montana struggles with _____ for the first time.

Her declining stardom.

What did Vin Diesel eat for dinner?

A pear salad and a protein shake.

What are my parents hiding from me?

You were an accident.

What’s the most emo?

Sunny Day Real Estate.

Make a haiku.

The old pond;

A frog jumps in —

The sound of the water._____ is a slippery slope that leads to _____.

Gay marriage. Interspecies marriage.

_____. That’s how I want to die.

Peacefully in my sleep, surrounded by friends and family.

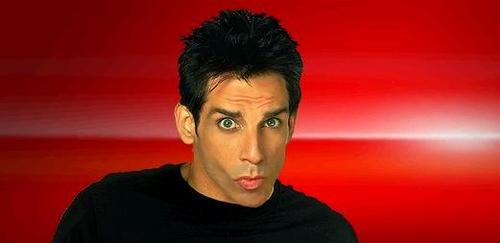

Being Really, Really, Ridiculously Good Looking

“I’m pretty sure there’s a lot more to life than being really, really, ridiculously good looking. And I plan on finding out what that is.”

~Derek Zoolander, Zoolander

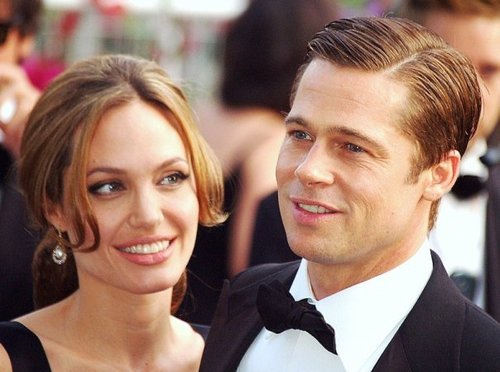

Humans like attractive people. Those blessed with the leading man looks of Brad Pitt or the curves of Beyonce can expect to make, on average, 10% to 15% more money over the course of their life than their more homely friends. Without being consciously aware that they are doing it, people consistently assume that good-looking people are friendly, successful, and trustworthy. They also assume that unattractive people are unfriendly, unsuccessful, and dishonest. It pays to be good looking.

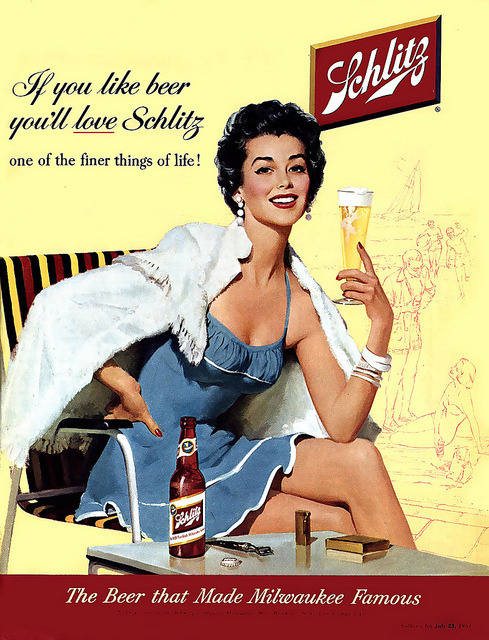

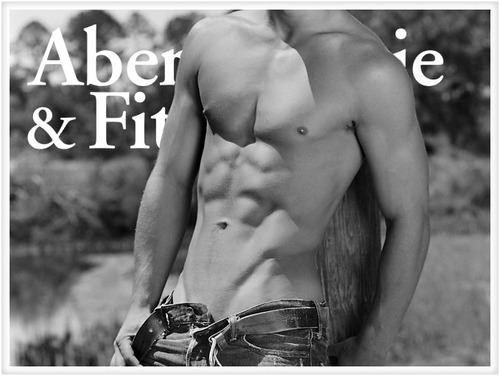

This insight is not lost on Madison Avenue or Hollywood. This is why every beer commercial features an attractive woman and Catherine Zeta-Jones appeared in T Mobile ads. This is why companies hire beautiful women to stand in their tradeshow booths and why Abercrombie & Fitch clothing stores badger attractive customers into applying for sales positions. Consumers associate the perceived positive characteristics of attractive people with their products and companies.

Abercrombie & Fitch might be able to sell more clothes by having good-looking sales associates, but is that legal? Surely, there must be some controls to ensure that unattractive people are not excluded from large swaths of the labor market. So what protections exist for those of us without smooth skin and thin waists?

The surprising answer is none. America has no law preventing companies from using attractiveness as a hiring criteria, regardless of whether the job is exotic dancer, salesman, or software engineer. It’s pretty much okay from a legal standpoint to discriminate based on looks in America.

Is that a problem?

The Science of Beauty

Beauty is often considered subjective and “in the eye of the beholder.”

To some extent this is true. People argue over the attractiveness of various celebrities precisely because differences of opinion exist. Tastes also differ across times and cultures. Victorian England admired pale skin. During the Colonial Era, men showed off their calves like men show off their pecs and biceps today. And skinniness has not always been considered the ideal.

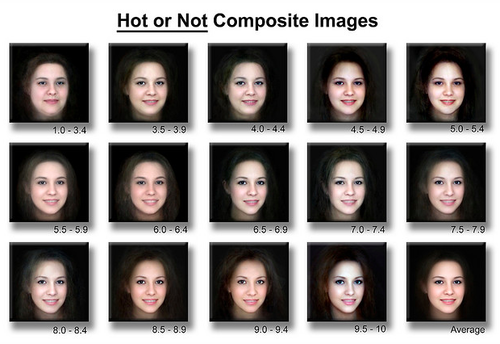

However, academic work on beauty finds that much of what we find attractive is consistent over time and across cultures. In general, people find symmetry and averageness of features attractive in faces. When images of perfectly symmetrical faces are created in Photoshop, people like them better. The same is true of photos created by merging many faces to get a composite. Scientists speculate that we prefer symmetry and average features because they (at least at some point) indicated healthy genes or other evolutionary advantages.

More evidence of a universal, objective basis for beauty comes from studies of babies presented with pictures of different faces. The pictures the babies gazed at the longest were consistently the ones rated as most attractive by panels of adults.

The Halo Effect

In the early 20th century, psychologist Edward Thorndike noticed that psychologists’ evaluations of very different traits in the same individual seemed suspiciously consistent. He suspected that a bias was to blame.

To test his finding, he asked military officers to rate their subordinates on characteristics such as neatness, physique, leadership skills, intellect, and loyalty. He again found that the results were too consistent. When officers rated a soldier especially high for one quality, they tended to rate him high for other unrelated traits where he did not necessarily excel. Soldiers rated especially poor in one area also received poor marks across the board. The officers opinion of their soldiers for one characteristic dominated their overall impression of them.

Thorndike called this the “halo effect.” Researchers have found it at work in many different ways, including physical attractiveness. Psychologist Robert Cialdini writes that “We automatically assign to good-looking individuals such favorable traits as talent, kindness, honesty, and intelligence.”

Attractive people benefit from the halo effect in two major ways in business, which are described by Cialdini in his bestselling book Influence.

The first is that people tend to “comply with those we like.” This is why magazine offers from neighborhood children are so irresistible and “Tupperware parties” (where mothers host parties to sell Tupperware to their friends) so successful. It’s also why Joe Girard, one of the most successful car salesmen of all time, sent all of his former customers holiday cards with the phrase “I like you” every year. Likeable people have an easier time selling products, and attractive people are eminently likeable due to the halo effect.

The second is that people tend to associate people with the products they sell and companies they represent. Cialdini points out that weathermen are blamed (by otherwise rational people) for storms and that messengers during the Persian Empire were either killed or treated as heroes depending on the nature of the news they brought. (“Don’t kill the messenger.”)

Ad agencies take advantage of this association principle all the time. Celebrity endorsements and imagery from popular events like the Olympics are used in commercials to link products or companies with their positive traits. The same is true of using attractive people in ads and showrooms, and it works even when people are perfectly aware of companies’ intent. Cialdini writes:

“In one study, men who saw a new-car ad that included a seductive young woman model rated the car as faster, more appealing, more expensive-looking, and better designed than did men who viewed the same ad without the model. Yet when asked later, the men refused to believe that the presence of the young woman had influenced their judgments.”

In combination, these two principles and the halo effect give attractive people a huge advantage in any job that involves interaction with customers, business partners, or the general public. Good looking public relations representatives are more likely to be trusted by the public and imbue their companies a positive image. Handsome salesmen will be more able to close deals. Sources will be more likely to trust beautiful journalists and tell them sensitive stories.

People generally recognize and tolerate the practice of hiring attractive people as actors and models. But the same principles that allow Angelina Jolie to do a better job selling makeup than the average girl next door are also at work in a huge number of professions.

A Quick Asterisk

While the halo effect has been robustly demonstrated to help attractive people in many personal and professional settings, there are important exceptions.

A 2010 study, for example, looked at how attractiveness benefitted men and women in different jobs. Attractive men had an advantage over their plain peers across the board. But for jobs considered “masculine,” such as mechanical engineer, construction supervisor, and even director of finance, women actually paid a penalty for being attractive. One of the researchers notes:

“In these professions being attractive was highly detrimental to women. In every other kind of job, attractive women were preferred. This wasn’t the case with men which shows that there is still a double standard when it comes to gender.”

This suggest that women may not benefit from attractiveness as much as men, or may even suffer reverse discrimination for it depending on the type of job.

The Best Looking Sales Staff in the Land

Although it is a clothing store, Abercrombie & Fitch is not strictly famous for its clothes. The company is also well known for it’s brand being tied to attractive people and pop culture. In their stores, pop music blares, perfume hangs in the air, and attractive sales staff use catchphrases like “Hey! What’s up?” Pictures on the wall feature their models’ six packs and bare backs more than the brand’s actual clothing.

Abercrombie & Fitch unapologetically hires only the most attractive people to work in their stores. Recruiters seek out attractive people in their stores, on the street, and at fraternities and sororities. The importance of their codified “Look Policy” is so important to hiring that managers reportedly throw applications from unattractive job seekers into the trash as soon as they leave the store.

Their focus on hiring attractive staff has worked. For its customers, A&F seems to have successfully associated the positive characteristics of its attractive employees with the brand and its clothing. Bought for $47 million in 1988 as an ailing sports focused clothing and goods company, its rebranding as a preppy and apparel store for teenagers resulted in strong growth. Abercrombie boasted $1.47 billion in revenue in 2012.

In 2004, 14 individuals launched a class action lawsuit against Abercrombie & Fitch. They charged that the company’s Look Policy of favoring a “natural, classic American style” was discriminatory. Their lawyers argued that a certain look was not central to the essence of A&F’s business. It helped market and sell clothing, but was unnecessary to the actual job of answering questions about polo shirts. A&F, rebuked, settled for $50 million and agreed to change their Look Policy.

But A&F did not get in trouble for hiring only hotties - they were charged with racism. Their accusers noted that A&F’s all-american look translated to “virtually all white.” The prosecution described how A&F sought out a sales staff that was mostly white and preppy, and relegated minority employees to positions in the back room.

Abercrombie & Fitch did not change their Look Policy to stop excluding unattractive people, it changed it to include good looking black, Asian, Indian, and Hispanic employees. The company still throws away resumes from people of average looks, and is proud of its good-looking sales staff.

No Law At All

There is no federal law against appearance-based discrimination or “lookism.” Companies in the US can freely use attractiveness as a basis for employment decisions in all but several cities that have passed local legislation against it. This is true regardless of whether attractiveness is central to the occupation (a stripper or actor), a branding or sales strategy (Abercrombie & Fitch’s sales staff), or completely irrelevant (personal assistant or software engineer).

Legal cases challenging companies’ use of physical appearance in hiring, promotion, or placement decisions have, as in the Abercrombie & Fitch example, linked the use of physical appearance to discrimination on the basis of race, gender, age, or disability.

Three laws exist that could be used to challenge lookism in company policy: the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, and the Americans With Disabilities Act.

1) The Age Discrimination in Employment Act protects older Americans from assumptions about their inability to perform their job. It has not been used in a case over attractiveness, but commentators in the legal field note that in cases such as the reassignment of an anchorwoman due to her appearance, the prosecution could have a claim under this act if they proved that she was moved to a less visible role due to her old appearance.

2) Title VII of the Civil Rights Act “prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.” The A&F case rested on this law’s prevention of racial discrimination. In the seventies, Southwest Airlines attempted to differentiate itself as the “love” airline. It hired only attractive female stewardesses and ticket clerks who dressed in hot pants and halter tops and called their check-in counters “quickie machines.” But in 1981, a man denied a job with Southwest successfully sued the company for sexual discrimination. Southwest began hiring male employees.

3) Although the Americans With Disabilities Act wasn’t originally intended to protect people without perfect, tanned bodies, its definition of a disability leaves room for interpretation:

“An individual with a disability is defined by the ADA as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment. The ADA does not specifically name all of the impairments that are covered.”

This act has been applied to physical characteristics, mostly (but rarely) in cases dealing with obesity (and, in one case, a toothless individual whose dentures were painful). In one obesity case, the judge invoked the logic of the halo effect, noting the disabling nature of obesity in employment in “a society that all too often confuses ‘slim’ with ‘beautiful’ or ‘good.’”

These acts do prevent one major appearance-based employment practice: hiring only attractive women for certain jobs. Since this would exclude men and place obligations (in terms of dressing seductively) on female but not male employees, it is banned by Title VII.

And the law is quite strict. Companies must prove that their employment practices constitute a “bona fide occupational qualification” that is necessary for the essence of the business. A strip club can claim that seductive women are the essence of the business. Southwest Airlines can not: the judge ruled that the company’s purpose was not “forthrightly to titillate and entice male customers.” Even Hooters, the restaurant chain whose entire premise is for hot, scantily clad women to serve men buffalo wings, fell victim to this law. It has kept the “Hooter Girls,” mainly by settling lawsuits out of court, but has been compelled to open more staff positions to men and women that do not require good looks.

Appearance-based hiring policies are open to legal challenge if they can be linked to one of the above three laws. But as long as a company is open to hiring attractive people of every gender, race, creed, and age, it is free to hire and promote staff the same way fraternity boys play hot or not. Further, since “lookism” is not explicitly banned, legal concerns and norms are much less likely to impact employers actions in practice.

In Defense of Abercrombie & Fitch

Many people rebel at the idea of Abercrombie & Fitch choosing to hire only good looking young people. Others, however, find “discrimination” on the basis of looks not only natural but good. Harvard economist Robert Barro, for example, finds good looks a legitimate aspect of productive economic activity:

“I believe the only meaningful measure of productivity is the amount a worker adds to customer satisfaction and to the happiness of co-workers. A worker’s physical appearance, to the extent that it is valued by customers and co-workers, is as legitimate a job qualification as intelligence, dexterity, job experience, and personality.”

Barro compares looks to intelligence. Both are valued to varying degrees in different positions and professions. Both are also doled out unequally. So just as we should not prevent intelligence from being considered a legitimate hiring criteria, neither should the law prevent beauty from being considered.

No one objects to actors and actresses being hired on the basis of their looks; they rebel at it being applied to jobs in sales or the press. But Barro notes that the market can better determine where beauty is a permissible criteria than the law can:

“The difference between glamour fields and others in terms of the role of physical appearance is merely a matter of degree. If the government stays out, the market will generate a premium for beauty based on the values that customers and co-workers place on physical appearance in various fields. Probably the market will allocate more beauty to movies, television, and modeling than to assembly-line production and economic research. I have no idea how much beauty the unfettered market would allocate to flight-attendant jobs or CEO positions. But whatever the outcomes, are the judgments of government preferable to those of the marketplace?”

According to this line of thinking, economic incentives will make sure that beauty is not considered in professions where it is irrelevant. After all, companies generally want to hire the best possible candidate. And in situations where looks are relevant to the job, companies should be free to consider it, and we can expect them to prioritize attractiveness depending on its importance to the job. This is analogous to how employers consider how much to prioritize intelligence over other traits such as honesty and teamwork depending on the role.

The Case For Lookism as Discrimination

Other legal thinkers believe that lookism is a form of discrimination. Just as protections over race or gender seek a society that is merit-based where people are not limited due to physical appearance, they believe that new laws should be put in place or the Disabilities Act extended to cover appearance-based discrimination.

Holders of this view engage in healthy debate with their fellows over whether such a law could be feasibly implemented. Common doubts include that the subjective nature of beauty would result in inconsistent application and the difficulty of identifying the unattractive population in need of protection. They also fear that it would “open the floodgates” to spurious lawsuits or doubt that unattractive people have been discriminated against historically the way that minorities and women have - a justification for legal intervention.

Barro and his ilk believe that lawyers should stay out of the beauty game. They think that the government should not legislate away the productive aspects of attractiveness that inform business strategies. However, some proponents of legal protection for appearance-based legislation make another claim. Just as Title VII and the Age and Disability Acts protect people from irrational biases about their worth as employees based on their race, gender, and age, they believe that unattractive people face the same irrational biases.

What’s Behind a Million Dollar Smile

So far, this article has considered how attractiveness gives people an advantage in certain jobs. And it is to this perspective that Barro gives a compelling response. However, beautiful people also benefit from their looks, professionally and personally, in ways that have nothing to do with better work performance. It could be considered as irrational, discriminatory, and in need of legal protection as the case of a woman being passed up for promotion because her employer doesn’t believe that a woman can be a leader.