goombagoomba

Shared posts

do u have a personal tumblr

goombagoombaLindo tumblr, por sinal.

yes, this nancy tumblr is a side tumblr to my main one:

Ultimate Virgin Ninja

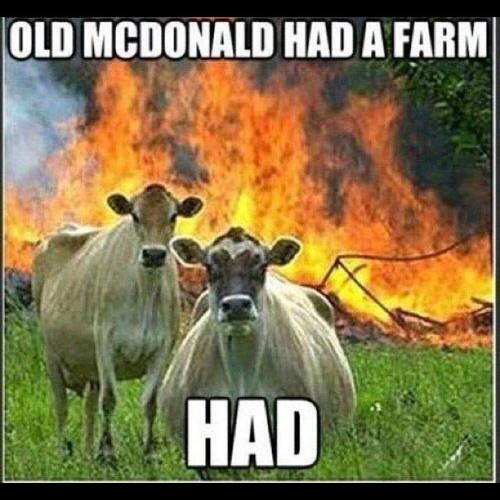

He really

Hates

all kinds

of water

inclusive COKE!!

Ultimate Virgin Ninja

Ultimate Virgin Ninja

Why Have Debates?

I find presidential debates painful to watch. The main reason is that isn’t they aren’t really debates, at least in the traditional sense of extended presentations of dueling arguments on a single, predetermined subject. When Abraham Lincoln confronted Stephen Douglas in 1858, the opening speaker spoke for an hour, was followed by a 90 minute response from his opponent, and then offered a 30 minute rebuttal (Lincoln and Douglas alternated speaking first). The encounter between Obama and Romney two weeks ago, by contrast, consisted of a series ten-minute segments in which the candidates answered questions posed by a moderator.

That format transforms ancient tradition of political rhetoric into a kind of dual interview. As such, it encourages the participants to pursue “zingers” and non-sequitur soundbites. There’s no question that Romney’s performance was more effective than Obama’s. Read in transcript, however, it develops no argument or vision.

There’s reason to expect that tomorrow’s encounter will be even more inane. One problem is the “townhall” format, in which voters ask impromptu questions. Leaving the choice of subjects to a moderator is bad enough: who cares what Jim Lehrer thinks is worth discussing? But soliciting questions from a relatively large audience almost guarantees incoherence.

A second problem is that participation in the townhall meeting will be limited to undecided voters. That means that they’ll be representative of only a tiny slice of the electorate: about 6% of likely voters, according to Reuters. Why should their questions have priority over other citizens?

It’s bad enough that citizens whose views reflect the vast majority of likely voters are excluded from the debate. What’s even worse is that undecideds are, speaking generally, the least informed and interested of likely voters. They haven’t made up their minds because they don’t know or care much about politics. As a result, they tend to be more concerned with character and manner than ideological commitments or specific policies.

The campaigns can’t be blamed for using debates to go after the few “sellable” voters who remain. Journalists and commentators, however, should not be shy about identifying the farcical character of the exercise. With the exception of the Nixon-Kennedy encounter in 1960, debates between the nominees became a regular feature of presidential politics only in 1976. Unless the candidates want to return to something resembling Lincoln and Douglas’s example, we’d be better off without them.

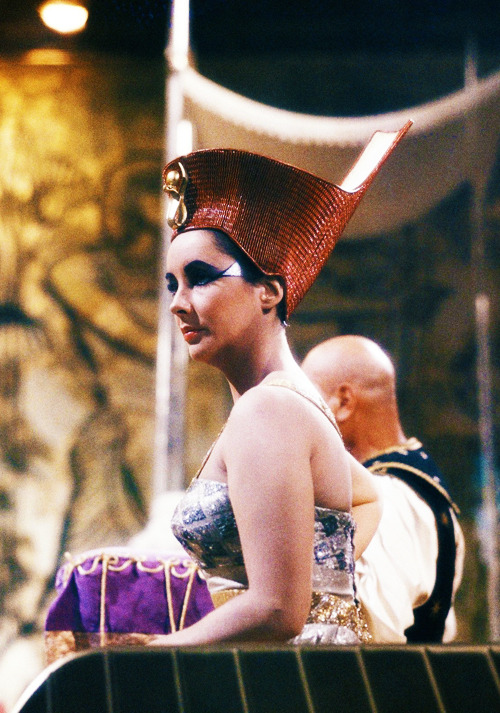

vintagesonia: Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra (1963)

goombagoombaQue bracinho maravilhoso, hein.

Romney Channels Obama on Foreign Policy

Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson says that he did not hear one concrete departure from the president's approach in the speech that was supposed to distinguish his Republican opponent.

I wasn't surprised that Romney's highly touted Major Policy Speech on foreign affairs Monday offered few specifics. But even in its generalities, Romney's tour d'horizon sounded very much like a speech Obama might have given recounting his overseas initiatives over the past four years.

Black Reds Under the Bed!

Mildly surprised to see Robert Merry plug The American Spectator’s Frank Marshall Davis piece, at least so uncritically. It’s a review of Paul Kengor’s biography of Davis, the American communist who was some sort of mentor to Obama in his teenage Hawaii years. Merry wonders why the mainstream press hasn’t made more of the Davis story–and what it says about Obama. I think that most people have decided it doesn’t say much of anything about Obama, in that probably half the people in politics today had some kind of extremist associations during their late teens and early twenties–whether the League of the South or SDS radicals. There are well-worn cliches about this.

But the Davis phenomenon points to an interesting wrinkle about American history. In one of his interviews, Kengor breathes a bit heavily about finding that the father-in-law of Obama’s associate Valerie Jarrett was also a communist. We’re being ruled by the Chicago Reds! But you know what? If you were a black American in the 1930s and ’40s, educated, politically active–and (this is the important thing) wanted to be involved in integrated politics, and work cooperatively with white people, the CPUSA was, if not the only game in town, pretty close to it.

I haven’t worked my way through Mark Naison’s scholarship on the subject, but I do recall being taken aside long ago by my late friend, historian and democratic socialist Jim Chapin long ago and had it explained that many blacks involved in mainstream Democratic politics had some sort of old CP roots, exactly for that reason. It was no surprise that one finds pretty bright traces of pink in the backgrounds of Jesse Jackson’s or MLK’s old advisors, because that was where the openings were for ambitious black Americans. Once America began integrating more seriously (which coincided with the Soviets coming to terms with the crimes of Stalinism) this particular niche of black radicalism dried up.

Communism was flawed in theory and evil in practice, but a lot of people saw it differently in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. To get some sense of the relatively normal, upstanding white people in the communist orbit, it might help to pick up Mary McCarthy’s highly readable The Group or Lionel Trilling’s sublime The Middle of the Journey. And they didn’t even have the excuse of segregation.

Intercollegiate Studies Institute

goombagoomba"the Dinner for Western Civilization" RYSOS.

Guest post by Seth Bartee

L.D. Burnett’s post on George Nash and her curiosity concerning a conservative organization by the name of Intercollegiate Studies Institute was most insightful and timely. The Intercollegiate Studies Institute is known by its acronym ISI by those most intimate with it. For some reason ISI is an organization that many scholars do not know about, and definitely should if they want to understand postwar conservatism and its intellectuals. ISI, originally known as the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists has been affiliated with the who’s who of American conservatism since 1953.

In this post I touch upon some of the major thinkers past and present that have defined ISI, and show the reach of this organization beyond the halls of academia. Additionally, one cannot be familiar with ISI without knowing about both its book press and scholarly journals or its annual events where ISI celebrates its history in the conservative movement. While ISI boasts a prominent place in postwar conservatism, lately the splits and sects that have spun off as a result of conservatives’ crisis of identity define it.

Journalist Frank Chodorov founded ISI in 1953, and ISI grew under the leadership of Victor Milione, who led ISI for thirty-five years (1953-1988). Russell Kirk, the intellectual father of postwar conservatism, gave ISI further credence when he co-founded Modern Age, one of ISI’s academic journals. Other prolific conservative intellectuals such as Will Herberg, Richard Weaver, Robert Nisbet, and John Courtney Murray published in ISI journals alongside Kirk. The publisher of conservative books (The Conservative Mindand God at Man at Yale), Henry Regnery, published, affiliated, and funded ISI’s activities as well; and the Regnery family still holds a prominent place at ISI, although they are no longer are involved in publishing.

ISI is still publishing conservatism’s most recognized scholars such as intellectual historians Wilfred McClay and Christopher Shannon, political philosophers Patrick Deneen and Peter Lawler, and poet/cultural critic James Matthew Wilson. All of the aforementioned scholars are active in the ISI speakers bureau, as it is one of the key ways ISI spreads its message to college students.

ISI’s influence goes well beyond college campuses and scholarly activities. The president of The Heritage Foundation, Edwin Feulner, is on ISI’s board of trustees along with Richard Allen, a former member of Ronald Reagan’s national security team. Other lesser known but no less important board members like Wayne Valis, who has worked in several Republican presidential administrations, is a well-connected political consultant who oversees Valis Associates which was instrumental in engineering the 2010 Republican takeover of the House of Representatives. Valis was a student member of ISI and remains involved in many of its functions. Past board members include Holly Coors, wife of Coors Brewing Company president Joseph Coors. ISI is also associated with a number of other conservative organizations such as The Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal, The Liberty Fund, and The Philadelphia Society.

I mentioned publications earlier. ISI has three hallmark print journals including The Intercollegiate Review, Modern Age, and The Political Science Reviewer and the online journal First Principles. ISI also houses ISI Books, which publishes standard academic press genres like biography, history, political science, philosophy, etc. Notably, Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn wrote the introduction for the re-issue of Philip Reiff’s The Triumph of the Therapeutic in 2006. ISI Books also features several series including Crosscurrents, which is a series that includes translations of books by foreign authors that ISI deems “conservative.” Chantal Delsol, Philippe Bénéton, and Pierre Manent are authors in this series. There is also the Foundations series that is directed towards families. This includes subjects such as homeschool instruction, and a children’s book of manners in which Joe Paterno wrote the foreword.

ISI also celebrates its conservative history with several annual events including the Dinner for Western Civilization that used to be located near ISI headquarters in the city of Wilmington, Delaware. The last two years the dinner has been hosted at The Harvard Club of New York City, a change brought about by its new president Christopher Long, who spent time working on Wall Street before taking ISI’s reigns. ISI also gives its own book award annually known as the Henry Paolucci/Walter Bagehot Book Award. Charles Taylor won this award in 2008 for A Secular Age.

L.D. Burnett wrote about communities of discourse in relation to ISI, and she is right here. As I showed above, ISI has created its own conservative community with events, publications, affiliations, and people that support the conservative cause. Certain and specific communities of discourse have developed in and around ISI, but this has also changed over its decades of existence. In my dissertation, I do not deal specifically with ISI but I am writing about three intellectuals whom were heavily involved with this organization during its peak years. ISI began as a fusionist organization meaning that they hosted an array of thinkers under the large umbrella of conservatism, which included anti-communists, traditionalists, southern agrarians, Roman Catholics, non-religious thinkers, capitalists, Republicans, Straussians, monarchists, libertarians, European émigré thinkers, and so on. Nevertheless, for the most part ISI has always leaned towards traditionalism with Kirk remaining its most celebrated intellectual.

However, as the first generations of postwar conservatives have passed on, ISI’s identity has shifted, too. From the many interviews I have conducted for dissertation research, the consensus is that ISI has become steadily more Catholic and Straussian, as a newer generation of conservatives have taken the reins at the Kirby campus in Wilmington (of course Catholicism and Straussianism are not synonymous among many of ISI’s Catholic scholars). Yet there are Catholic Straussians, and depending on what kind of conservative you speak to (neo-conservative, traditionalist, reactionary…) concerning this aspect, this may or may not be a good thing or this may seem a complete falsehood altogether. As a side note, you can find some of these issues debated in The American Conservative and at various blogs including Peter Brimelow’s VDare and Taki’s Magazine.

ISI does have certain social and intellectual boundaries, although many of them remain unwritten. ISI is not an organization for a world-weary evangelical or a populist. It has a defined bourgeoisie Catholic, even a high-protestant sensibility, although some would argue this point given that apologist Dinesh D’Souza is a featured lecturer. However, it is my understanding that D’Souza’s presence is more for publicity purposes than intellectual viability.

This is where in my dissertation I have utilized a concept known as textual communities. A textual community is community that forms around specific texts where meaning is rendered by a privileged interpreter. A privileged interpreter, as defined by Brian Stock, is someone who not only translates a text, but they give a text a new life, and live out the text, which others then live by and promulgate as members of a textual community. Russell Kirk was a privileged interpreter, because of the special status of The Conservative Mind to generations of American conservatives. Kirk defined what it meant to be a Burkean to his followers, and boundaries were set by Kirk during his lifetime, and then by his textual community after his death. The greatest segments of Kirk’s textual community filtered into ISI, although many now reside at The Kirk Center at his home in Mecosta, Michigan.

Generations of Kirk’s followers know Kirk’s rendition of Burke and are not necessarily Burkeans ex nihilo. This is not to say that ISI’s conservatives are blind followers of Kirk any more than to claim that all neo-pragmatists have no real understanding of John Dewey or Charles Peirce. The concept of textual communities, as defined by intellectual historian Brian Stock, is meant to demonstrate how ideas are passed on and then change through successive generations. I am not going to go in depth about the background of Stock’s research, but he used the backdrop of the Middle Ages to study religious heresy, thus to demonstrate that humans often follow particular interpretations of texts and not the text themselves. In other words, humans take ideas often twice removed if not more.

ISI has changed since Kirk’s death in 1994. ISI’s desire to remain an umbrella organization has brought it into conflict with conservatives of conflicting priorities. Paul Murphy recounted one of conservatism’s most seminal conflicts in his monograph The Rebuke of History. The now famous controversy between M.E. (Mel) Bradford and William Bennett for the chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) chair, which pitted the neo-conservatives against the traditionalist or paleo-conservative wing of conservatism, eventually had greater implications, one that reverberated through ISI’s rank, although the implications were not immediate.

Essentially neo-conservatives successfully homogenized conservatism by getting rid of what they considered the racist and backward element of conservatism, its traditionalist wing. Michael Kimmage recounted a part of this process in his monograph The Conservative Turn as well. The traditionalist wing became more reactionary after three Republican administrations they considered less than conservative and often as reliant on the guidance of government as their supposed liberal foes. Gradually, this filtered into ISI who of course were friendly to neo-conservatives and Republicans while attempting to maintain its focus on traditionalist conservatism. The second year of the Bush administration was kind of the breaking point for the longtime alliance. In reaction, ISI, especially the Kirkean element, essentially drew up firmer boundaries around ISI, although I cannot stress enough ISI’s dependence on funding, which for the most part is considered to be in the hands of neo-conservative organizations. When thinking of ISI, one might picture the geography of a major metropolitan area. There is the core (city center) but after that, there are neighborhoods and suburbs that make up the metropolitan area. There are textual communities within the textual community; discourse on top of discourse.

As Web 2.0 grew, so did the ability of traditionalist conservatives to focus their voices throughout the blogosphere. Patrick Deneen, formerly at Georgetown and now at Notre Dame as of fall 2012, founded the Tocqueville Forum at Georgetown and created an important blog by the name of Front Porch Republic (FPR). Deneen promotes “Place. Limits. Liberty” through his favorite thinkers/writers including teacher Wilson Carey McWilliams and novelist Wendell Berry. FPR blog posts touch upon religion, masculinity, food and drink, and almost anything else under the sun. Other conservative scholars such James Wilson, Ted McAlister, Darryl Hart, and Jeremy Beer have joined the FPR blog as frequent contributors.

Peter Lawler has conceptualized what he terms “postmodern conservatism.” He keeps a blog by that title at the journal First Things and blogs at Big Think, too. Lawler keeps a friendly but lively debate with the Porchers (FPR), as he calls them. The Berry College professor is a lively public speaker who often dazzles students with his interesting take on culture; including a well-known lecture on the television show Mad Men. Kirkeans have grouped at the online journal The Imaginative Conservative and The University Bookman—a publication associated with the Kirk Center and edited by Kirk scholar Gerald Russello.

While Lawler, Deneen, and many Kirkeans are still on friendly terms with ISI, other traditionalists such as Paul Gottfried are suspicious about the legacy of traditionalism left to ISI alone. Gottfried is a retired academic who has written a score of academic monographs that have dealt with American conservatism, most recently Leo Strauss and Straussianism. Gottfried is probably most known for his Marxist trilogy, where he theorizes on the roots of managerial society and therapeutic liberalism. Gottfried knew Kirk and corresponded with him, and he knew just about everyone who was anyone in American conservatism including Murray Rothbard and Richard Nixon. Gottfried was friends with Christopher Lasch, as the two reconnected during Lasch’s populist turn in the 1980s. Gottfried became more discontented with the Republican Party and neo-conservatives because of things like global democracy, and what he considers a therapeutic language garnered from the opponents of Bradford. He is equally concerned about the axioms the neo-conservatives coalesce around such as the universalization of morality and degradation of history, especially the idea of historicism, which Strauss derided in his book Natural Right and History.

Gottfried has taken a pro-active approach to combatting neo-conservatism, often to the ire of his former colleagues. He eventually broke from ISI, The Philadelphia Society, and Academy of Philosophy and Letters (which is its own kind of splinter group, too). Gottfried eventually formed The HL Mencken Club (HLMC) that meets annually in Baltimore. The Mencken Club and APL are traditionalist organizations looking to re-establish, recreate, or renew conservatism to something else other that what it is now. I attempt to flesh this out in my dissertation. As far as textual communities go, you will find that Kirkeans are localists, but not historicists, like Gottfried. The APL has a humanistic approach to conservatism as opposed to Gottfried, who wants to see conservatism become more “offensive” in their approach to politics and liberalism. The HLMC attracts a variety of dissenters while the APL is more bourgeois. Despite these sects, many of these members still publish in similar venues and congregate together on occasion.

ISI has lost some of its influence because of the proliferation of conservative thought in blogs and splinter organizations, but there is another factor, too. Conservatives are no longer the only scholars researching conservatism. Blogs like USIH and many academic historians such as Michael Kimmage, Paul Murphy, Kim Phillips-Fein, Patrick Allitt and others have made seminal contributions to research on conservatism. A student looking for research on conservative intellectuals need not only look inside the many pages of ISI journals and books. However, it is still probably the best place to begin primary source work when studying American conservatism. Even if ISI is going through a period of change, it is still an interesting community of scholars, college students, professionals, and laypeople. As you will find, many of ISI scholars participate in other historical associations such as USIH. As Kim Phillips-Fein suggested in her lead article on the current state of research on American conservatism last year, there is still plenty of room for recontextualizing conservatism and its intellectuals.

Página rasgada

Stray Thoughts on History and Politics

Former NPR reporter Andrea Seabrook recently debuted a new podcast called "DecodeDC" that promises to "decipher Washington's Byzantine language and procedure, sweeping away what doesn't matter so you can focus on what does." So far, at least, it's a solid piece of work, worth listening to if you're interested in politics and have fifteen minutes or so to spare. But what struck me about the first two episodes (all that have appeared so far) is that each begins with history. Episode 1, House of (mis)Representatives, concerns the enormous number of people represented by each Congressperson today, and the political problems that arise as a result. Why are there so few members of Congress for a nation of our size? The answer (probably well known to readers of this blog) is that, after frequently increasing its size during its decennial reapportionment process as the nation grew, Congress froze its membership at 435 in 1911 and it's essentially stayed there ever since, while the country has grown from 92 million to 308 million people. Episode 2, Mind Control, concerns the (non-rational) use of language as a political tool. It starts with a history of the Republican habit of calling the Democratic Party "the Democrat Party." Relying on an old William Safire column, Seabrook credits Harold Stassen with coining the term while working for Wendell Willkie's presidential campaign in 1940. After starting with history, each episode quickly moves on to other things. DecodeDC isn't about history, after all. The second episode, in particular, doesn't make much out of the particular origins of the "Democrat Party."

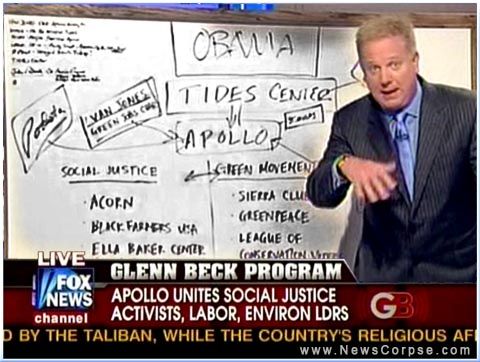

Former NPR reporter Andrea Seabrook recently debuted a new podcast called "DecodeDC" that promises to "decipher Washington's Byzantine language and procedure, sweeping away what doesn't matter so you can focus on what does." So far, at least, it's a solid piece of work, worth listening to if you're interested in politics and have fifteen minutes or so to spare. But what struck me about the first two episodes (all that have appeared so far) is that each begins with history. Episode 1, House of (mis)Representatives, concerns the enormous number of people represented by each Congressperson today, and the political problems that arise as a result. Why are there so few members of Congress for a nation of our size? The answer (probably well known to readers of this blog) is that, after frequently increasing its size during its decennial reapportionment process as the nation grew, Congress froze its membership at 435 in 1911 and it's essentially stayed there ever since, while the country has grown from 92 million to 308 million people. Episode 2, Mind Control, concerns the (non-rational) use of language as a political tool. It starts with a history of the Republican habit of calling the Democratic Party "the Democrat Party." Relying on an old William Safire column, Seabrook credits Harold Stassen with coining the term while working for Wendell Willkie's presidential campaign in 1940. After starting with history, each episode quickly moves on to other things. DecodeDC isn't about history, after all. The second episode, in particular, doesn't make much out of the particular origins of the "Democrat Party."But DecodeDC's use of history in its inaugural episodes, is I think, symptomatic of at least one of the ways in which history is frequently referenced in contemporary American political discourse. If one's goal is to "decode" or "decipher" American politics, one of the most popular methods of doing so is to reveal some (presumably obscure) fact from the past that will explain (or can be presented as explaining) why things are the way they are today. In the case of DecodeDC, these reveals are pretty straightforward. But this use of history comes in more baroque versions, too...such as Glenn Beck's infamous whiteboards. In each case, one of the purposes of this use of history is simply to denaturalize the present: if something that we take for granted has a (quasi-secret) starting point, perhaps it can change in the future. In the more conspiratorial versions of this move, the genealogical reveal also shows a (quasi-surprising) person or force pulling the strings of the present from behind the scenes.

I've been thinking a lot about the role of history in politics (and vice versa) in light of the recent passing of Eugene Genovese, Eric Hobsbawm, and Henry May. Though all three have been discussed on this blog, more attention has been given Genovese and May, presumably because, unlike Hobsbawm, they were Americanists. Elsewhere online, however, Hobsbawm and Genovese seem to dominate the discussion. And what most clearly distinguishes them from May is that both were, more obviously and deeply than May, engagé historians, though the relationship between history and politics in their work was far more complicated than the history-as-code-ring we get from Andrea Seabrook (let alone Glenn Beck).

Both Genovese and Hobsbawm, of course, started their careers (and Hobsbawm ended his, as well) as Marxists. Marxism provides a particularly rich theoretical connection between politics and history. And in the work of more sophisticated Marxist historians (a category that surely includes both Hobsbawm and the younger Genovese), the understanding of the historical record and of political theory mutually inform and shape each other. Like its Hegelian predecessor, the Marxist understanding of history sees the possibility of reading the future out of the record of the past. But for Hegel, unlike Marx, the future foretold by history was, essentially, the Prussian present. Leopold van Ranke, and the other German historians who helped create modern historical practice in the 19th-century, also tended to be politically conservative, essentially seeing history as proving that what is ought to be.

But for all of these thinkers, on the left and the right, history was complicated, though in an ordered way. This complexity was preserved even when, on occasion, they engaged in a version of the decoding / debunking mode (I'm thinking, in particular, of The Invention of Tradition, which Hobsbawm co-edited). Though history certainly involved recovering past things now forgotten, for history to be understood, let alone for it to serve a political purpose, it needed to be properly interpreted. The job of the historian does not end at simply figuring out that Harold Stassen was the first person to say "Democrat Party."*

During my early years of graduate school, my fellow history students and I frequently told each other that much of what was wrong with American political life could be solved if only Americans could have a richer, more complicated understanding of history. I remember one student fantasizing that if historians were regularly invited on Oprah, they could totally transform the discourse on that show for the better. Another student, watching Reagan's farewell address with me during our first year in grad school, was simultaneously enraged and excited by Reagan's discussion of the importance of teaching history: "we've got to teach history based not on what's in fashion but what's important." Though he and I knew we didn't agree much with the President about the relationship between the "fashionable" and the important in history, we certainly shared his passion for teaching about the past...and his sense that teaching about the past could help mold the future.

While I continue to believe that doing (and teaching) history is important in many ways, including for our political life, I've long since lost the sense that simply doing good history is a panacea for the problems in our political culture. To begin with, good history always has to compete with bad history. And though good history occasionally wins, bad history often has the political edge. And simple history will almost always have an advantage over complicated history. Invoking "Munich" (or "Vietnam") as codewords in a foreign policy debate is far easier than grappling with the complexity of European politics in 1938 or the American presence in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and 1960s.

However sympathetic one is (or isn't) with Hobsbawm's or Genovese's politics (and I imagine that few are sympathetic with both Genovese's youthful politics and the politics of Genovese's later years...though of course, Genovese managed the trick), it's hard not to conclude that their political understandings enriched their (and, by extension, our) understandings of the past. Yet I think neither of them -- even Genovese, late in life, allied with a regnant conservatism -- had anywhere near as significant a political impact as an historiographical one.

____________________________________________________

* To be fair to DecodeDC, Seabrook does analyze Stassen's coinage, but in largely ahistorical terms. George Lakoff is the most important analytic voice in the podcast's second episode.

Romney’s Foreign-Policy Speech: More War, Bigger Budgets

Mitt Romney’s speech at VMI today confirmed every realist’s and non-interventionist’s worst fears about him: not only is his foreign-policy vision indistinguishable from that of George W. Bush — except that it may be more utopian and Wilsonian — but there’s no indication that any realist has the slightest influence on his strategic thinking.

That includes political realists: anyone who might convey to Mitt what a price the GOP paid for Bush’s wars in 2006 and 2008 — the price it will pay again in 2012, the way Mitt is going. Romney promised military Kenyesianism and was as demagogic as the best-paid Pentagon lobbyist in claiming “our defense spending is being arbitrarily and deeply cut.”

He attacked Obama for failing to extend America’s mission in Iraq — “America’s ability to influence events for the better in Iraq has been undermined by the abrupt withdrawal of our entire troop presence” — as if many more months (or years?) and untold scores of American lives lost would have done for Baghdad what eight years of nation-building failed to do. That’s a war Americans of all political backgrounds (even, quietly, not a few neoconservatives) are glad to see the back of, yet Mitt wants more. With a mindset like that, how long will he keep America’s sons and daughters fighting in Afghanistan?

He stopped short of saying he would send troops to Syria and Iran on day 1, but he telegraphed a clear commitment to brinksmanship and regime-change:

Iran today has never been closer to a nuclear weapons capability. It has never posed a greater danger to our friends, our allies, and to us. And it has never acted less deterred by America, as was made clear last year when Iranian agents plotted to assassinate the Saudi Ambassador in our nation’s capital. And yet, when millions of Iranians took to the streets in June of 2009, when they demanded freedom from a cruel regime that threatens the world, when they cried out, “Are you with us, or are you with them?”—the American President was silent.

… I will put the leaders of Iran on notice that the United States and our friends and allies will prevent them from acquiring nuclear weapons capability. I will not hesitate to impose new sanctions on Iran, and will tighten the sanctions we currently have. I will restore the permanent presence of aircraft carrier task forces in both the Eastern Mediterranean and the Gulf region—and work with Israel to increase our military assistance and coordination.

… In Syria, I will work with our partners to identify and organize those members of the opposition who share our values and ensure they obtain the arms they need to defeat Assad’s tanks, helicopters, and fighter jets. Iran is sending arms to Assad because they know his downfall would be a strategic defeat for them. We should be working no less vigorously with our international partners to support the many Syrians who would deliver that defeat to Iran—rather than sitting on the sidelines.

This was not a speech he had to make — a speech distracting from the ground Romney had recently made up by refocusing his attention on the plight of America’s middle class. And if he had to make a foreign-policy speech, it did not have to cater to the neoconservatives and pork hawks already on his team. Nothing in this speech appeals to a war-weary and economically troubled people. It’s politically damaging. But he gave this speech anyway, and the only reasonable explanation is either that Mitt really believes — zealously — what he says, or else he’s entirely compliant to the ideological demands of right-wing Wilsonians. I suspect the latter is the case, and that portends a Romney presidency that would repeat all the errors of his Republican predecessor. The issue here is not even a reckless foreign policy versus a domestic policy that may give Republicans grounds for hope: a foreign policy like this will not permit much of a domestic policy at all. It will consume a presidency, just as it consumed George W. Bush’s.

P.S. Romney didn’t take Danielle Pletka’s advice: even the chief hawk at the most neoconservative think tank warned beforehand that “Mr. Romney needs to persuade people that he’s not simply a George W. Bush retread, eager to go to war in Syria and Iran and answer all the mail with an F-16″ and “Criticisms of Mr. Obama’s national security policies have degenerated into a set of clichés about apologies, Israel, Iran and military spending.” I suspect a new tune will be sung now that the speech has been given, but it’s telling that Romney has outdone AEI itself in pushing an unrelenting “Long War” line.

Is the Republican Party Racist?

goombagoombaPerguntar não ofende, né.

Now that Romney supporters have sought to make race, once again, an issue against Obama with an "explosive" five-year-old video reminding voters that Obama (yes, it's true!) consorts with black people, perhaps it's time to remind people of the real reason Romney deserves rejection at the polls in November: He is the candidate of the neo-racist Republican Party.

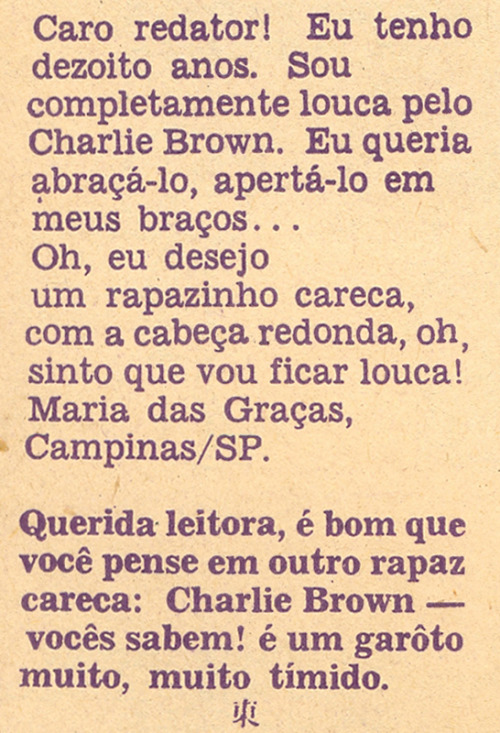

Hi! I've found your tumblr totally by surprise and loved it. Me and my boyfriend always come here to check the new scans. I knew only a bit about Nancy (she's not very popular where I live - Brazil -, although there were comic books of her translated to P

goombagoomba~~~<3

Hi! Thank you so much for your very kind message !!!! Thats a very big compliment! Where i live Nancy is not so known either, but thanks to the internet i can find and buy it all :) Thank you!