Yeah, totally boring academic title, but there's a point to it. Here in this online community, we tend to err on the side of rational analysis, and I'm going to be a stinker and point out how much politics shapes what passes for rationality. For example, if we were a rational species, there wouldn't be 20 million-odd people in Southern California where I live, because the area's semi-desert at best, and the only way people can live here is to have water pumped in from hundreds of miles away. If history and archaeology are any guide (going back to Mesopotamia), cultures that relied on long-distance irrigation have inevitably fallen when their water systems failed, and there's no reason to think southern California will be any different. So why are there so many people in this evanescent "paradise" that is southern California? Politics. Politics turns rational proposals, such as John Wesley Powell's 19th Century rational proposal to dam some western rivers and irrigate a bit of farmland, into the unsustainable sprawl of pork-barrel dams and water works that is the American West today. That's why I'm talking about political economy, not just economics: this isn't just about money, it's also about political power. That's what makes it more interesting, complex, and yes, irrational.

Speaking of rational proposals for restructuring civilization, there's one out there, by Stanford engineering Professor Mark Jacobson. He proposes that, by 2050, the US can supply its power needs entirely through renewable sources: photovoltaics, solar thermal, wind, waves, and hydroelectric dams (see The Solutions Project, among many others). Here I'm not going to analyze Dr. Jacobson's proposal in much detail, because most of you are more tech savvy than I am, and you're perfectly capable of doing that yourselves. What I'm more interested in is what politics could do to this rational proposal, and what kind of an America would result.

On the good side, if we switch to using 100% renewable electricity globally, we'll have stopped emitting both greenhouse gases and nuclear waste, and this is a very good thing indeed, especially if you want to avoid the 100,000 year-long Altithermal I wrote about in Hot Earth Dreams. Also on the good side, there seems to be no physical reason why we can't do it. On the bad side, well, let's just say that mirror shades will come back into fashion.

At the Solutions Project website, Dr. Jacobson outlines how much each power source would contribute to the energy budget of each US state. He assumes that we'll be able to get by with less energy, mostly because quite a lot of fossil fuel energy is wasted as heat, and that energy won't get wasted by things like solar panels. He also assumes that we'll develop progressively better batteries or energy storage technologies (he goes for hydrogen, I prefer ammonia), so that by 2050 or so we'll power everything from aircraft to bulldozers from sustainable electricity stored in one form or another. While I have no idea whether it's better to electrify a D-6 caterpillar, run it on ammonia, or to start from scratch and design an electric mule-analog moving an updated Fresno scraper, for the sake of this essay, I'm going to assume that Jacobson's ideas are broadly feasible, and that we can get away with switching to running civilization on 100% renewable electricity, possibly with some changes to his formulae.

Since I've already done the calculations for California (link to blog entry), I'll just repeat a table here as an example of the kinds of changes Jacobson proposes. The table below shows the rough difference between how California got its power in 2014 and how Jacobson proposes we can get it in 2050, by percent:

• Coal: -100% (we go off coal completely)

• Natural Gas:-100% (natural gas too)

• Oil: -100% (yup)

• Nuclear: -100% (ditto, because politics)

• Biomass: -100% (putting sequestered carbon back into the air is stupid)

• Hydroelectric (all forms): -61%

• Geothermal: -36%

• Solar (all forms): +627%

• Wind (all forms): +142%

• Wave and Tidal: N/A (grows from zero to one percent)

• Unspecified Sources of Power: -100% (California currently gets some power from "unspecified sources," while Jacobson specifies everything)

Let's unpack the renewables. First off, Jacobson's plan relies a lot less on hydropower from dams, and that's probably a good thing. Basically, all the good dam sites in the US were built on decades ago (per Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert), and there's somewhere north of US$50 billion dollars of maintenance needed for the 84,000-odd dams we already have in the US (source). In my blog, I recently posted about some of the other problems dams have (link). The tl;dr version is that dams have serious issues with sediments and salt, the 50-100 year design life of many of them is ending Any Day Now, although their functional lives can be prolonged by that $50 billion of maintenance we're ignoring. Various sources (cf this New York Times article and its references) don't think that new large dams are cost-effective anywhere in the world. One can hope that the craze for building huge dams ends worldwide. Really, they're just like the pyramids, the end result of older powerful males with bad cases of Edifice Complex.

Geothermal doesn't have such problems so far as I know. It just isn't as big a piece of Jacobson's pie.

Solar power, in Jacobson's model, has four components: residential photovoltaic (PV), commercial and government rooftop PV, commercial PV plants out in the boonies, and boonie-sited concentrated solar thermal plants, like good ol' Ivanpah. Of these, Jacobson's model has rooftop PV supplying 13% of California's power (that's commercial, government, and residential rooftop PV combined), while solar plants provide 26.5% and solar thermal plants provide 15%. Some have argued that this is probably too much for solar thermal, and I happen to agree with them. Still, whatever the mix of technologies, this is a lot of big power plants, all sited outside cities. Where are we going to put them all? To satisfy Jacobson's plan, solar will have to grow by 627%, from supplying less than 4% of California's energy to over half, albeit half of a reduced energy total.

Wind has its own issues, and the number of turbines needs to more than double. Tidal energy is still largely in the design phase, but we'll need to put whatever turns out to work for tidal power generation off our ever-so-scenic coasts.

That's just one state out of 50, and each state has its own mix of power sources. Jacobson's group really did a lot of research and modeling, and he put much of his work online (see The Solutions Project, among many others).

Of course it gets more complicated, because most of the US west of the 100th meridian (aka the West, formerly the Great American Desert) is running out of both rainwater and groundwater. If you want the gory details, go read Marc Reisner's Cadillac Desert (actually, read it anyway, it's muckraking journalism at its finest. It puts Chinatown to shame). The bigger point is that there are thousands of dams in the West, irrigating a total acreage about the size of Missouri (per Reisner). East of the 100th meridian, such farmland is largely watered by "godwater" raining from the sky. In the West it's watered by irrigation from dams, often built as pork barrel projects that deliver as few as five cents on every dollar invested in them, but which made voters happy.

Many Western farms also rely on non-renewable groundwater. In the case of the Ogallala Aquifer, which underlies farmland from the Dakotas to Texas--the land of the Dust Bowl--that land is being farmed using an aquifer is being managed so that it will be depleted in 50-100 years, with 35 percent of the land going out of production in the next 30 years (reference). California's San Joaquin Valley is probably in as bad shape, but we haven't monitored our groundwater until very recently (reference). Over time, the groundwater will run out, and I strongly suspect that the bigger farms will be replaced with solar plants. This isn't instant famine, because far too much irrigated ag land is growing things like alfalfa and other cattle feed, or export crops like almonds. Still, the Ogallala Aquifer grows about 20% of America's cattle, corn, cotton, and wheat, so its progressive loss means less food for an increasingly crowded world, and less of culturally critical products like beef, bread, and cotton.

But you're trying to figure out what these dry figures have to do with cyberpunk and electricity, I suspect?

Let's start putting it all together. In places like California, the current building trend is to build mixed-use subdivisions of closely packed homes surrounding a mixed-use mall that includes a grocery store and various services. This is all very rational, boring, and anonymous, living spaces separated from shopping spaces, residents required to get in their cars and drive to their jobs, which are typically located in different areas due to all sorts of tedious zoning regulations. As Jacobsonian electrification takes hold, these old subdivisions will get retrofitted with rooftop solar and electric cars, then decay as their design inefficiencies become ever more burdensome (for instance, many burb homes are power hogs that are only livable when you run the air conditioning all day). These older burbclaves will also get (forcibly) wired into smart grids that bring in power from big solar plantations out in the boonies where none of their residents is supposed to go. The newer developments will pack people ever tighter, if you believe the current Visionary Planners, warehousing them in a largely artificial environment where everything from food to water to power to material goods to residents are completely imported, and the light-polluted night sky is the color of a flat screen on standby. Those people who can't work at home will still have to commute, because rational urban planning has the bad habit of separating living and working into different geographic areas, so that you can't live above the shop. Given how Koomey's Law will keep dropping the energy requirements for computing power for probably another few decades, these congested new urban burbclaves will probably be wired from the rooftops to peoples' shorts, assuming our foolish infatuation with Big Data won't go away any time soon (why did nature evolve the ability for brains to forget, I wonder?). Big Brother will be watching, at least when he's not obsessing over all the false positive correlation patterns your life is randomly throwing up.

Where are all those new wind and solar plants going? That's where it gets political. As Gibson once wrote, the street finds its own uses for things, but in this case, we're talking about K Street in Washington DC. Some of the biggest farms in California are already owned by everything from oil companies to insurance companies, so when solar gets more profitable than whatever they're currently subsidized to grow (i.e. when their groundwater runs out), they'll solarize. In other cases, as at Ivanpah, and as I saw in the first solar boom of 2009-2011, plants will get proposed in all sorts of stupid places, with international investors relying on the political pull of their K Street contacts to sweep aside whatever legitimate concerns the environmentalists and local residents throw up. As with all the pork barrel dams that got built between 1940 and 1980, I'm quite sure that, once the US gets religion about solar plants, there will be a profusion of badly designed, stupidly sited solar and wind plants, built to enrich companies and get some politician re-elected on the promise of sustainable growth powered by sustainable electricity. By now it's a fine American tradition, despite Congress's showy attempts to rein in government spending.

That's the Suits side of our cyberpunk future, all very rational, designed, over-simplified, and bureaucratic, from the warehoused humans to the solar plantations to the super-rich megacorps. What about the punks?

Solar has always had its rebellious side. For decades it's been the power of choice for people wanting to unwire themselves and get off the grid, and just because the grid has gone solar, it doesn't mean that people will stop trying to use solar to power their freedom. One of the biggest fears of the current power companies (like my own SDG&E) is that homeowners will simply put up solar panels and unwire themselves, leaving the companies with a grid to maintain and too few customers to maintain it. They're fighting back, predictably, by trying to make going off the grid impossible, and that conflict will doubtless continue for decades.

That's the thing about renewable energy. Unlike legacy energies, like oil, coal, or nuclear, wind and solar can be used on the small scale, by people trying to carve out their own space rather than being wired into The System. The polymorphous nature of renewable energy will play out in a really complex dance, as the Suits struggle to keep people in The System so that it can generate profits, while the "punks" (often well-to-do, but still punks in their self-conception) use the same power to free themselves from the parts of The System they don't like. It's a fight that's happening now, and it will only get more intense as solar and batteries get cheaper and options proliferate.

There's another aspect to the various grids. They need to get smart, to accommodate the increasingly fluctuating power supplies and demands caused by renewable energy being dumped into them by thousands of small suppliers. And that causes a huge problem.

The problem isn't the need to build better batteries and energy storage, because everyone needs better batteries for all those new electric bulldozers and things. People like Elon Musk are trying to get fabulously wealthy building batteries, and some will undoubtedly succeed. There are even other energy storage options, like tiny ammonia synthesizers that produce a few gallons of ammonia off wind power. Ammonia's a lot like natural gas in terms of energy storage, but it doesn't have any carbon in it.

No, the problem is simpler and more dangerous: smart grids are hackable. As we come to depend on them, we make ourselves more vulnerable to anyone with an effective cyberweapon, from a lone wolf hacker to a foreign government. Of course, if we stay with dumb grids, we're condemning ourselves to a much more dangerous future of severe climate change, so either way is dangerous. Still, sustainable electrification changes the face of conflict. Rather than bomb a city and invade, a coercive cyberforce, military or otherwise, can hold utility systems hostage until the enemy politicians give in to their demands. The potential for long term human misery is largely the same as in conventional war, but the weapons are much less lethal, at least in the short run, and therefore more appealing to hawkish politicians. Personally, I don't ever want to be trapped in a city without water, but that might happen one day to get my city to pay ransom or something. Anyway, a smart-grid future is a future of black hats, white hats, red queens, and Wired Wars replacing World Wars. The cyberwarriors won't jack their brains directly into cyberspace, because that's too slow and, anyway, neurosurgery will get more dangerous as multiple antibiotic resistant bacteria become the norm. But that doesn't make cyberwar any less dangerous.

Ready for your mirrorshades yet? This is a 2030s America of decaying suburbs retrofitted for solar, newer, urban burbclaves (crushclaves?) of people warehoused in smart apartment complexes, the spiritual descendants of Roman insulae, with everything and everyone piped into them, housing people stripped of their history in particular places, given the option of living artificial, highly controlled lives, and sometimes rebelling, whether or not there are bread and circuses (or national health care). There will be solar-roofed and often tiny homes all over rural America, while refurbished rural service stations swap batteries rather than pump gas, strange new construction equipment builds (perhaps prints?) new buildings, and planes bumble across the sky on electric engines. If we use ammonia as our renewable fuel, smog will be a common problem (ammonia burns to NOx, a common smog pollutant), and meth will be the cheap street drug of choice (ammonia can be used to make it), but at least their tailpipes won't emit greenhouse gases. The West's currently irrigated, salt-poisoned ag lands will revert piecemeal to desert, and rural Westerners (or their megacorp employers) will follow the Saudi Arabian example of exporting power and importing food and water. We may come to share the Saudi embrace of religious conservatism, too. Some western cities will dry up and blow away (Las Vegas), while others will tough it out (probably the holy city of Salt Lake, the birthplace of Western irrigated agriculture). Still others, like Los Angeles, will continue to reinvent themselves as manufacturing and commercial hubs that import everything from water to power to food to people, at least until the earthquakes hit. After that, who knows? Some Okies will pack their electric jalopies and move north and east to tend godwater farms, while the country struggles to settle millions (but hopefully not hundreds of millions) of climate refugees.

The megacorps will strive to order and simplify our lives, for that is where they get their power, while the hackers try to free themselves, and perhaps us, by making our lives as disorderly and complex as possible. But it's not a question of who wins. It's an ever evolving new landscape, a red queen race with an unknown number of contestants. Sustainability is not static.

Unfortunately, electrification is not necessarily sustainable either, because so much depends on how the End of Oil plays out. Currently, some predict that demand for oil will peak in 2035 (source), and if we're still burning oil by 2050, we're in for severe climate change. Others say that the US, which is sitting on the biggest shale oil deposits in the world, has a crumbling oil industry that is spending more than it is earning and may not recover from its current depression (reference). Currently, Big Oil has tremendous political power, and they're perfectly willing to use it to everybody's detriment. Then again, Big Coal had a huge amount of political power not too long ago, and that industry is collapsing as we speak, due to market forces. Politics and economics are inextricably linked, like it or not.

How will it all play out? No one knows. Still, it's just possible that we'll make it to a brighter, more sustainable future. And if we do somehow make it to this bright and shiny future, we'll definitely need shades.

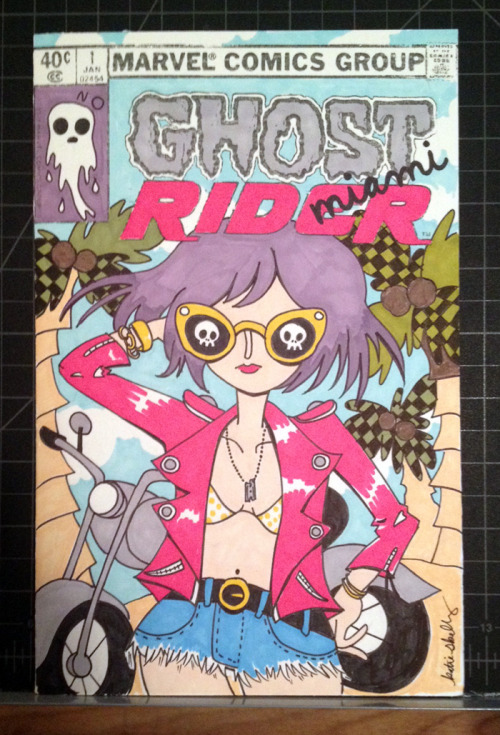

If Katie Skelly’s Nurse Nurse represented a young artist stretching her limits in her first major work, then her follow-up book, Operation Margarine, sees Skelly working more in her comfort zone. There were times in Nurse Nurse when it seemed that Skelly wasn’t entirely comfortable drawing certain aspects of her Barbarella-inspired space fantasy. She simply didn’t have the chops to convey some aspects of the story, which led to some whiplash narrative shifts. That said, she still followed through and worked around her limitations as best as she could. Cartooning can be seen as a series of problem-solving exercises, and Skelly presented herself with a high degree of difficulty with her first book.

If Katie Skelly’s Nurse Nurse represented a young artist stretching her limits in her first major work, then her follow-up book, Operation Margarine, sees Skelly working more in her comfort zone. There were times in Nurse Nurse when it seemed that Skelly wasn’t entirely comfortable drawing certain aspects of her Barbarella-inspired space fantasy. She simply didn’t have the chops to convey some aspects of the story, which led to some whiplash narrative shifts. That said, she still followed through and worked around her limitations as best as she could. Cartooning can be seen as a series of problem-solving exercises, and Skelly presented herself with a high degree of difficulty with her first book.