|

Stephen the Little

Stephen the Little was a skinny, middle-aged ordinary white dude from Montenegro who became the supreme dictator of his country by somehow convincing all of Western Europe that he was Tsar Peter the Third of Russia, a feat that was made much more difficult by virtue of the fact that it was a relatively well-known fact that Tsar Peter the Third of Russia was very very dead and there were quite a few Russians who had been there when it happened. Willfully ignoring any and all challenges to his obviously-untrue wild statements about being at the top of the Russian Imperial royalty food chain, Stephen the Little improbably embedded himself as the glorious leader of Montenegro, brought a period of unprecedented peace the region, ended political infighting among the people of the Balkans, personally fought off a massive Turkish invasion force with nothing more than an unruly pitchfork-swinging mob and ridiculous amount of luck, resisted the political intrigues of Catherine the Great, and then died in his bed content in the knowledge that he was the greatest and weirdest hero his country had ever known.

Awesomely enough, we really don't know much where this guy came from. Maybe he really was the Tsar, and truly had escaped from a tragic fate at the hands of would-be assassins to seek asylum with his Slavic brethren (he wasn't). Maybe he actually was a hero sent by God to deliver the people of Montenegro from the clutches of Ottoman tyranny (also unlikely). Our best guess is that he's probably just some regular Serbian guy from Montenegro, though some historians speculate he might have been from Russia or possibly somewhere on the Dalmatian Coast near Herzegovina. Nobody knows for certain, which is part of what makes it so fucking cool. Hell, we don't even know the dude's real name Montenegrin history refers to him only as Šćepan Mali, meaning either "Stephen the Little" or "Stephen the Small" depending on the translator, although even that's a weird oxymoronic epithet because contemporary sources basically describe this dude as being a totally average, unremarkable guy of ordinary height, normal physical strength, and generic looks. All we really know for sure is that in 1767 a thirty-five year old dude named Steve showed up on the border of Montenegro wearing the ragged robes of an Orthodox monk and telling everyone he was Tsar Peter III, the former (but now deceased) supreme ruler of All the Russias a man who by all accounts had been strangled to death four years earlier on the orders of his wife Catherine the Great and was now being used as fertilizer in an undisclosed location somewhere in Imperial Russia.

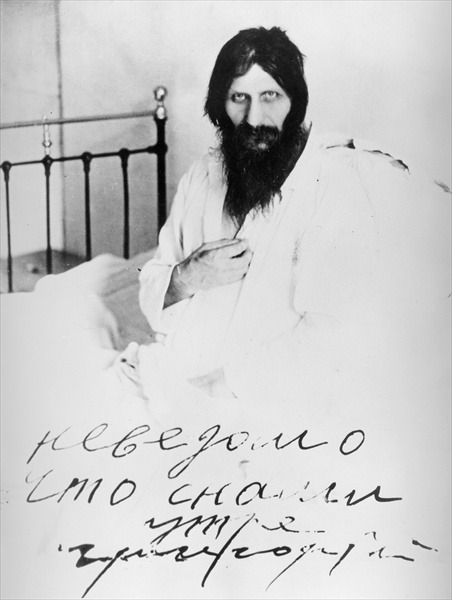

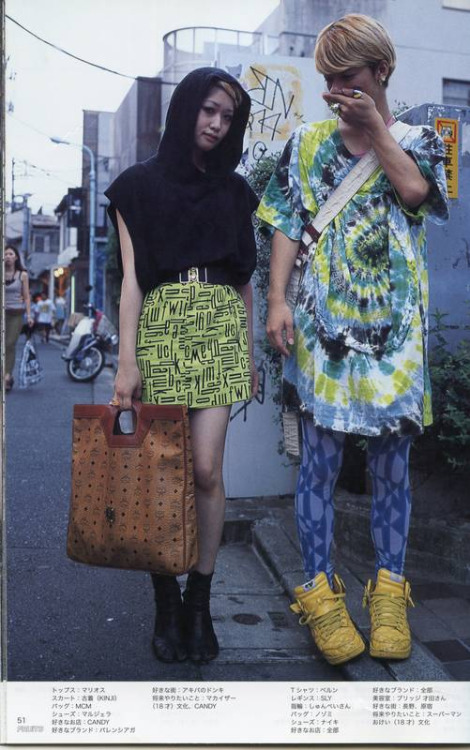

This is not Stephen the Little. It's Tsar Peter III.

Please note that he looks absolutely nothing like the guy at the top of the page.

Sure, this wasn't the first time some jackass had gone around trying to convince everyone he was Russian royalty, but up until this point roughly every attempt at retconning your way into Russian history earned the imposter a one-night-stand with excruciatingly painful death. About a hundred years earlier some asshole showed up in Russia claiming to be Ivan the Terrible's son Dmitry (who was also dead, BTW, beaten to death by Ivan in a bout of drunken nerd-rage after a heated debate about whether Klingons or Jem'Hadar were the most badass alien species in Star Trek), but after a couple weeks of that nonsense the False Dmitry broke his leg jumping out of a palace window in a futile effort to avoid the angry mob that eventually tore him apart limb from limb and had his pieces shot out of a cannon in the general direction of Poland (where the imposter was allegedly from). That worked out so well for him that two other dudes decided THEY were going to be False Dmitries as well, and both of them ended up being decapitated within months of their announcements and then having their heads used as doorstops and paperweights in the Imperial palace.

So, I guess we've established that it took some balls to come out in Early Modern Eastern Europe and make wild accusations about being royalty, but it just so happened that Stephen the Little's nickname was definitely not a reference to his gigantic brass ones. In addition to an excess of testicles, Steve also had two Russian guys who swore he was really the Tsar, and the three of them had this amazing and completely untrue tale of heroism about how they all escaped Catherine's assassins, fled across Russia, got thrown in prison, escaped in a daring display of vertical leaping and other badassitude, then ran through waist-deep snow barefoot in the rain uphill both ways until they'd reached Montenegro. The story, while compelling in it's over-the-top pulp fiction radness, didn't convince the supreme ruler of Montenegro at the time -- a decrepitly-old Bishop named Sava who had actually met the real Tsar Peter. But, whatever, that guy was feeble and powerless and nobody pays attention to old people anyways so the citizens of Montenegro flipped out, baked a gigantic cake, made Stephen the ruler of their Council of Nobles, and had the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church send him a fucking awesome new horse. Once he was in charge, Stephen used cunning, diplomacy, and his own magnetic natural charisma to unite the warring tribes of Montenegro for the first time in centuries, organize the first national census, order construction of a massive network of roads, and set up a central police force that was allowed by law to cap thieves and robbers and other criminals on sight. He was beloved by his people, brought crime to an all time low, and somehow momentarily convinced Yugoslavian people to stop killing each other all the time. One awesome old historian claimed that this guy's ability to successfully run a country should have been proof enough to the people of Montenegro that he wasn't the actual Tsar Peter, because that guy was a fucking tremendous tool and Catherine probably did her country a favor by having that douchebag whacked in an alley somewhere.

The Real Tsar Peter III's horse.

Ok, so as you might have guessed, Tsarina Catherine the Great of Russia was a little interested to hear that there was some asshole running around claiming to have boned her, so she sent a powerful Russian noble and thirty of his best men to publicly declare that Stephen the Little was definitely not her ex-husband. When the Russian delegation reached Podgorica, Steve personally met them at the gates of his capital with open arms, three gigantic casks of his finest vodka, and two dozen of the hottest women in Montenegro.

He had found the Russians' weakness.

The Russian delegation left a week later, content with having Stephen the Little serve one day of house arrest in his palace bedroom as punishment for his crimes. Despite most of these guys HAVING BEEN THERE when the real Tsar Peter III was executed, none of them said shit about this guy not actually being the true fugitive dictator of Russia.

Somewhere a trio of False Dmitries rolled around in their graves.

Well hello there.

By this point in history the Ottoman Turkish Empire had blitzed throughout Greece and now shared a border with Montenegro, and these guys really weren't too keen about living next door to a unified Christian mountain kingdom cohesively organized under a competent ruler. Naturally, the Sultan decided to wax them into oblivion. He put together a force of 60,000 of the most feared warriors in the world, marched into Montenegro, and proceeded to start laying waste to everything he could find. Stephen the Little responded by putting together 10,000 Montenegrin volunteer citizen-soldiers armed with pitchforks and foul language (they couldn't afford bullets or gunpowder) and decided, what the hell, it's worth a try. He formed a solid wall of Serbian-ness across the narrow Ostrog Mountain Pass outside the town of Niksic and prepared to do his best impression of Leonidas holding the Gates of Thermopylae.

The Turks were the most technologically advanced army in the world. Sixty thousand men who had conquered all that stood before them for centuries, these battle-hardened asskickers were equipped with state-of-the-art muskets, cannons, and grenades, and they were more than capable of jamming them up the asses of anyone who fucked with them. They outnumbered the defenders six to one (maybe more according to one source this battle was 100,000 Turks vs. 2,000 Montenegrins), didn't give a shit about anything, and were more than confident that they were going to beat these guys so hard that their grandchildren would be born with congenital birth defects and weird-shaped dented heads.

But Stephen the Little's men were mostly Serbians, and if there's one thing you should know about the Serbs, it's that these guys love to fight. And they're pretty good at it.

The Turks attacked, hurling everything they could at the defenders in a bloody, vicious battle that took a grisly toll on both sides, each army's men lashing out with everything from bayonets and musketballs to wooden spears and running knee strikes to the ballsack. When the smoke cleared on a vicious day of no-holds-barred face-stomping, the Montenegrins were seriously fucked-up, obviously, because despite what this website might lead you to believe that's typically what happens when you're outnumbered by an obscene margin by guys who are better equipped and better trained than you. But still, despite being badly bloodied and losing almost half of their army, the Montenegrins held the line, and Stephen the Little, blinded in one eye by a nice heaping dose of shrapnel to the face, continued to urge them to fight on and defend their homeland.

Modern-day Montenegrin military training. Yeah.

The next day it rained like a motherfucker, and nobody wanted to come out and fight because they didn't want to get their hair wet and also because gunpowder doesn't work in heavy rains. The day was cold and miserable and the only cool thing was when an awesome bolt of lightning streaked down from the sky, hit a powder keg in the Turkish camp and blew up in a gigantically-fucking-rad mushroom cloud that everyone agreed was totally Metal.

The next morning, the Turks packed up their shit and left. They ignored the shattered Montenegrin Army, marched off into the distance, and left Stephen the Little standing alone on the battlefield.

Stephen was a hero across Eastern Europe overnight. Sure, we later found out that the Russians had been in the middle of planning an attack while the Ottoman Army was away, so the Sultan was forced to order his army to stop wasting time ob this Fake Peter asshole, turn North, and go beat the shit out of some real Russians instead, but fuck it, right? If this public relations genius could convince the entire world he was a dead Tsar that bore absolutely no physical resemblance to him it wasn't that much of a stretch to think he could dial this up as, "I'm a war hero who defeated the Ottomans because God is on my side, and the only reason they're currently beating the piss out of Russia is because they know they were overmatched by our military power." Which is of course exactly what he did.

Stephen the Little was the champion of Christendom. Songs and praises were sung not only among his own people (who were already convinced he was the greatest thing since LeBron James), but throughout Europe, with tales of his "epic victory against impossible odds" being told from the British House of Commons to whatever the fuck the 18th century equivalent of the New York Times was in the New World. Nobody else fucked with Stephen again, and he ruled competently and intelligently for the next six years. He died in 1774 when he was strangled to death in his sleep by his personal barber, a Greek dude who was being paid off by the Turks to turn on his boss. Everything in Montenegro kind of went downhill from there.

Sources/Links:

Denton, William. Montenegro. Dalby, Isbister & Company, 1877

Pavlovic, Srdja. Balkan Anschluss. Purdue University Press, 2007.

Roberts, Elizabeth. Realm of the Black Mountain. Cornell University Press, 2005..

Stevenson, Francis Seymour. A History of Montenegro. Elibron, 2005.

Tozer, Henry Fanshawe. Researches in the Highlands of Turkey. Kessinger, 2004.

Wikipedia

Main

The Complete List

About the Author

Miscellaneous Articles

RSS

| Powered By WizardRSS.com |

Full Text RSS Feed |

Amazon Plugin Wordpress |

Android Forums |

Wordpress Tutorials

A schematic showing the layers of Earth’s atmosphere.

A schematic showing the layers of Earth’s atmosphere. Joe Kittinger in his Air Force days.

Joe Kittinger in his Air Force days.