This is how things go in the US, where law enforcement is treated like a favored religion and everyone who isn't on the inside is just grist for prosecution mills. Here's the setup, via Matt Pearce.

A Baton Rouge police officer was arrested Friday on a count of negligent homicide, accused of going 94 mph in a Corvette when he caused an off-duty crash on Airline Highway that killed an infant and injured six others.

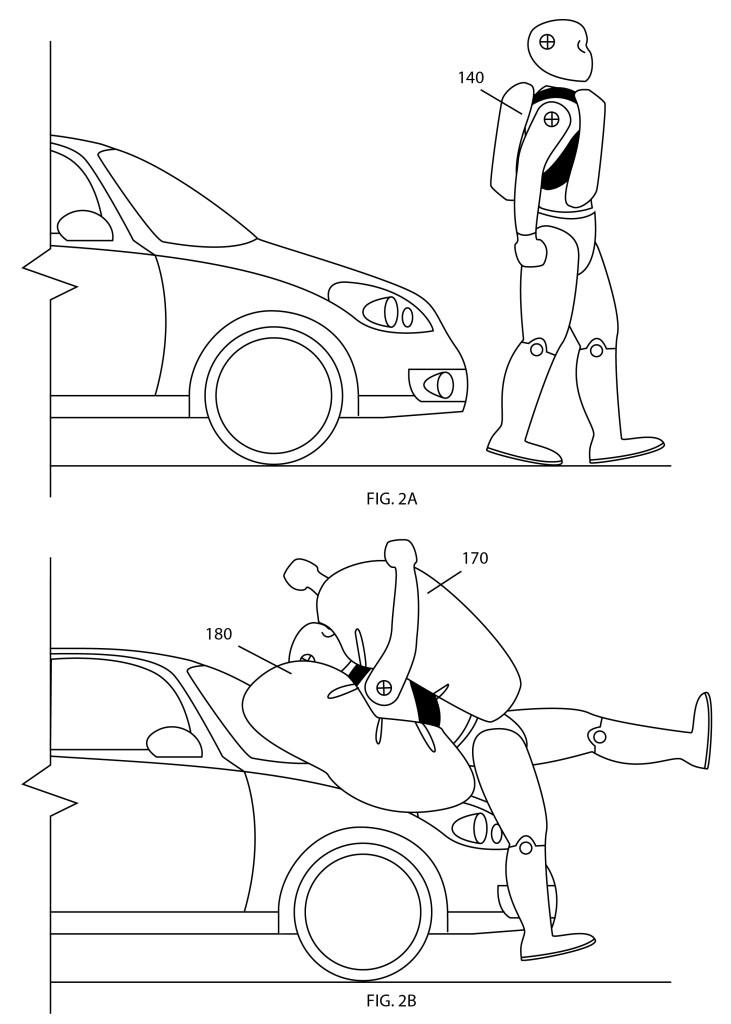

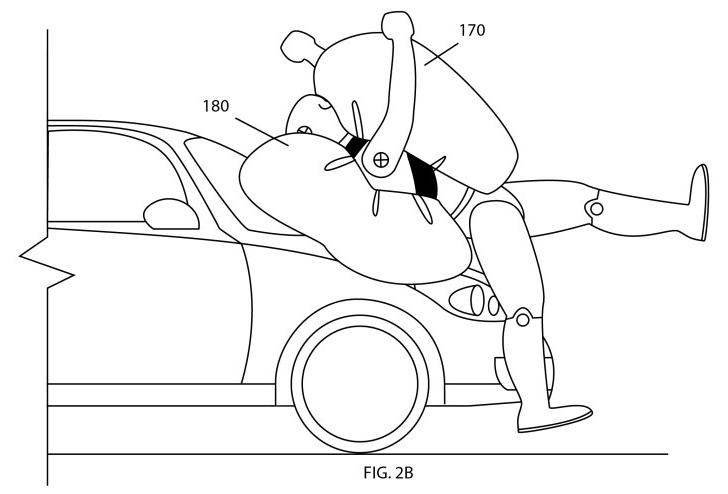

The officer, Christopher Manuel, 28, was driving north in a 2007 Chevrolet Corvette shortly after 8 p.m. Oct. 12 on Airline Highway when it struck a Nissan at the intersection at Florline Boulevard that was occupied by four adults and three children.

All of the occupants of the Nissan were taken to the hospital. One of those passengers, a 1-year-old baby, Seyaira Stephens, later died.

The van made a left turn in front of the off-duty officer. Both vehicles had a green light. The speed limit on this road was 50 mph. The speed the officer was traveling was verified by his Corvette's black box. Here's the positive news:

Manuel, of 8508 Greenwell Springs Road, was booked into East Baton Rouge Parish Prison on a count of negligent homicide and speeding, Sgt. L'Jean McKneely, police spokesman, said.

The officer was booked and made bond. So far, so good. Here comes the avalanche of bad news.

Manuel, who has been on paid administrative leave since the accident, will remain on paid leave until after an internal investigation is concluded, McKneely said.

Due process, I suppose, even if it was clear the officer was traveling at nearly twice the posted speed limit. Much of the information needed to conclude the investigation was already in his department's hands, thanks to the Corvette's airbag control module, which recorded this data at the time of impact.

But if there's going to be any justice done, it's going to be severely delayed.

That investigation will not begin until he recovers from his injuries and is released to work by a doctor.

That's the sort of thing never extended to lowly civilians. No officer has ever told an injured arrestee to heal up before worrying about answering questions. No law enforcement agency has backburnered an investigation simply because its subject can't move around on their own yet.

But these investigations took no time to complete. No one at the Baton Rouge PD waited around for victims of the officer's reckless driving to be fully healed before they began their arrests.

Just weeks after a Baton Rouge police officer was arrested on negligent homicide and accused of causing a crash that injured several people and killed a baby, the child's mother was also arrested on the same charge because police said she failed to properly secure the baby's car seat.

Brittany Stephens, 20, was arrested Tuesday after police found that her daughter's car seat was not secured and the straps were not adjusted correctly for the child's height, according to her arrest report. Police said the "lack of securing the seat to the vehicle and the loose straps are a contributing factor in the death" of the child and "show gross negligence" on the mother's part.

Ah, the healing power of criminal charges, brought against someone involved in an accident that was no fault of her own. She (and her daughter) were just passengers in the van. Not to worry, the police issued citations to everyone else in the vehicle the officer hit. But the mother of the infant the cop killed is facing the same charges he is. And she's not going to be given a chance to rest up before the police move forward with their investigation. The PD has already wrapped this one up and forwarded charges to the DA's office.

East Baton Rouge District Attorney Hillar Moore III said Tuesday his office has not yet determined whether Stephens or Manuel will face charges, but prosecutors "will review all reports, charges and arrests and make the appropriate decisions based upon facts and law."

There is nothing right about this, not even technically. The reckless driving performed by the officer should nullify the culpability of the people in the car he hit. While Officer Manuel may have had the right of way, his excessive speed changed the contours of the incident. In a case involving law enforcement officers manufacturing a reason to stop a car, a court pointed out unsafe driving by officers nullifies moving violations performed by other drivers.

[T]he Court finds as a matter of fact and law that Defendant did not fail to yield to the cruiser because the cruiser was not proceeding in a lawful manner. Rather, the cruiser was itself speeding on a dark, rainy night at low visibility further compromised by road glare. By proceeding in such a reckless manner – and in violation of both state and local law – Ofc. Davis forfeited the preferential status afforded a lawful driver under the right-of-way statute.

This isn't apples-to-apples (the court making this declaration was in Ohio, not Louisiana, where this accident took place) but it's a good rule of thumb. If someone is driving 44 mph over the speed limit, they've effectively forfeited their right-of-way status. A left turn taken in front of a speeding officer should give the officer zero preferential treatment in the eyes of the law. The officer should be 100% culpable for the damage and loss of life. Arresting a mother who lost her infant to an officer's reckless actions is needlessly cruel and serves zero deterrent purpose. Her daughter can't be killed again.

The way the Baton Rouge PD is handling this ensures Officer Manuel's eventual conviction will also have zero deterrent value. It shows officers the PD is willing to arrest victims of their unlawful actions and give them all the time they want -- with pay! -- to heal up before they're forced to confront the results of their recklessness. If the DA is smart, the charges against the mother will vanish and the cop will be rung up for his negligent actions.

Permalink | Comments | Email This Story

A Brooklyn judge has ruled that because the New York Police Department (NYPD) used a cell-site simulator, also known by the brand name Stingray, to track down a murder suspect without a warrant, some evidence against the suspect will be thrown out. A...

A Brooklyn judge has ruled that because the New York Police Department (NYPD) used a cell-site simulator, also known by the brand name Stingray, to track down a murder suspect without a warrant, some evidence against the suspect will be thrown out. A...