» Over the decades, cities change size, but they gain and lose population in varying ways: Some in-town, some on greenfield land. How does that impact our understanding of population change?

Every few months, the U.S. Census releases new data on population change, chronicling the rise and fall of America’s cities, counties, and regions as they grow and shrink. The data are fascinating, bringing us useful insights about migration flows and economic shifts. They also point to fundamental changes in the places Americans live: Houston over Chicago, Phoenix over Philadelphia, and so on. And they produce breathless news reports that emphasize that the fastest-growing places are 15 cities you’ve never heard of.

Yet as data are released and evaluated, the trends as described by the levels of information presented by the Census often fail to directly represent underlying facts about how cities are changing–or they at least do not do so adequately. Comparing the changes in population size in the Birmingham and Buffalo regions, for example, explains very little about the health of their respective center cities. Comparing how the cities of Houston and New York have grown overall tells us little about how their in-town neighborhoods have held up over time.

This post delves into the question of how to measure population growth in urban environments by examining frequently used measures of demographic change and comparing them to alternatives. It is geared toward a discussion of demography rather than transportation, but its implications are important for how we think about cities and their component parts, including transportation. Indeed, as I’ll delve into in this article, the question of what cities are growing and what cities aren’t is at the core of some of the most pressing debates in today’s urban planning–so understanding how a place’s population change is occurring is essential.

Levels of data reporting

The U.S. Census collects data about people, either as a full sample (on decennial years) or using sample-based estimates (through the American Community Survey). These data are aggregated by the Bureau to different geographical levels. Depending on the sample used and the year collected, they are aggregated to the block, block group, tract, place (city), county, metropolitan statistical area (region), and other geographies, which are then used by analysts to make conclusions about the way in which the country’s population is changing.

The typical way for demographers to make comparisons between centers of population is to use regional (MSA) data and to track their changes, as MSAs provide a broad view of a place’s demographics and offer insight into how that place is evolving, regardless of political boundaries. The justification for this approach is based on the fact that boundaries in different places work differently.

For example, the city of Philadelphia is the major center city of its region (and jobs center), and it happens to share borders with Philadelphia County, the major county in the region. On the other hand, while Boston is the largest city in its region, the city of Cambridge next door has a large share of the region’s jobs and many of its dense, urban neighborhoods. Meanwhile, while Boston is in Suffolk County, there are other municipalities also in Suffolk County, and Cambridge is not in Suffolk County. As a result, comparing trends in Philadelphia with Boston as cities or Philadelphia with Suffolk as counties with one another at the national level could result in inappropriate conclusions.

Yet there are significant tradeoffs in using a regional level of analysis, as well. Indeed, every level of analysis has advantages and disadvantages, as summarized by the following table.

| Level |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Region (MSA) |

- Represents broader economic and commuting geography.

- Does not require abiding by “arbitrary” political boundaries.

- Allows reasonable region-to-region comparisons.

|

- Fails to account for differences in politics between jurisdictions, which may influence growth. MSAs are not political entities.

- Masks issues occurring at the local level and fails to compare suburb to suburb or inner city to inner city.

|

| County |

- Usually has fixed boundaries.

- Counties at the center of a metro area often represent the “inner city” dynamics of a place.

|

- Counties typically have minimal political power compared to states and cities.

- Counties are rarely “understandable” for lay people.

- A county in some cases can be regional in scope (Bexar, TX) or just be a part of a city (New York, NY).

|

| City (“place”) |

- Cities are the base level of local jurisdiction most people understand, so they are relatable.

- Cities often have strong political environments that likely influence growth significantly.

|

- Boundaries change over time, especially in Sunbelt cities with annexation powers.

- City trends do not necessarily represent the region as a whole, and suburbs are usually cities in their own right, confusing matters.

|

| Tract, block group, block |

- Represent local-level trends most effectively.

|

- Do not represent broader trends.

- May not accurately represent “neighborhoods” because of arbitrary boundaries.

|

How, then, can we compare cities across the country with one another? If no Census geography is problem-free, are cross-regional comparisons useless?

The answer is to first determine what it is, exactly, that we are trying to ask. If the question is, for example, which areas of the country are growing most quickly, looking at regional demographics make sense (rather than, say, emphasizing large percentage growth in tiny cities). If the question is whether different political approaches are affecting growth differently, then examining population in cities may be effective.

But if the question is something more complicated, such as how similar neighborhoods in different places around the country are acting, these Census geographies often cease to be relevant. This is particularly important for understanding transportation trends, since the way people move around is often directly related to the physical characteristics of the places people live and work. But cities or regions as a whole rarely respond to this issue because cities are often too big and inadequately uniform.

Components of urban population change

More than just pondering the rather simple (but important!) question of what metropolitan regions are growing or declining most quickly, I wanted to get a better sense of how specific parts of regions changed over time. I wanted to be able to answer questions more relevant to urban transportation patterns, like how downtowns in various cities grow or shrink over time. Downtowns are almost uniformly the places in urban regions with the highest transit, walking, and biking mode shares; their health is indicative of whether a region is moving in the right direction on that front. Similarly, how much are already-developed areas of cities changing over time? This is particularly relevant for understanding the pace of infill development, to determine whether cities are adapting to become denser places, or whether they are focusing on suburban growth instead.

To conduct this analysis, I moved beyond the standard Census geographies and to create more appropriate and nationally comparable methods. Taking as a base the 100 largest U.S. cities in 1960 (many of which, though not all of which, are the same as today’s 100 largest cities), I compared changes in not only (a) the overall population within city boundaries, but also (b) the areas of those cities that were already built up in 1960 (with a density of at least 4,000 people per square mile*), and (c) the areas within 1.5 and 3 miles of city hall, irrespective of whether those areas are within the relevant city or not.

The following four maps illustrate how these geographies look for four representative cities–Las Vegas, Indianapolis, Houston, and New York City. The cities have changed dramatically between 1960 and 2014. Las Vegas, Indianapolis, and Houston increased the area within their city boundaries dramatically through annexation or, in the case of Indianapolis, a merger with the surrounding county. New York City, on the other hand, has the same boundaries, with the exception of some landfill such as at Battery Park City.

The areas that were built up in 1960 also differ considerably between the cities. Whereas most of 1960 Indianapolis had neighborhoods of densities of more than 4,000 people per square mile, less than half of Las Vegas did and Houston’s density was arrayed along corridors emanating from downtown. Finally, while the areas within 3 miles of Houston city hall are entirely within the city, those within 3 miles of Las Vegas and New York city halls include suburban jurisdictions (including parts of New Jersey, in the case of New York City).

When examining just a comparison between changes in population in the city as a whole and those in the neighborhoods that were already built up in 1960, some remarkable trends become apparent.

As the following interactive graph shows (mouse over the graph to get more information; not all cities are shown in the X-axis), very few cities saw significant overall growth between 1960 and 2014 in neighborhoods that were already built up. Houston and San Antonio, which each gained hundreds of thousands of people overall during that period, also each lost more than 100,000 people in their already-built up areas. So did Indianapolis, Columbus, Louisville, and Memphis. What’s surprising is that these are cities often acclaimed for their dramatic growth over the past few decades. Yet their growth has been premised largely on annexation–suburbanization–even as their already-built up cores have declined.

In fact, the average of the 100 largest cities grew by 48 percent overall. Yet the average city also lost 28 percent of its residents within its neighborhoods that were built up in 1960.

Some cities did expand through infill quite dramatically, and Los Angeles is a true outlier on this front, gaining almost 1,000,000 people in areas that were already at least partially built up. Other coastal cities had similar but less dramatic trends, like San Diego, San Jose, Long Beach, Miami, San Francisco, Seattle, Arlington (VA) and Oakland. San Francisco is often singled out as a place where growth is not moving fast enough, yet this chart illustrates that the city is at least as willing to accept infill growth as most others.

Of course, change from 1960 is just one criterion to measure change in urban environment. The following graph illustrates how the built-up neighborhoods in 1960 fared over the next few decades. In some cases, they rebounded from significant declines in the 60s and 70s; in others, their populations have continued to fall. (Note: this paragraph and the following graph added in a post-publishing update.)

Looking at areas within 1.5 and 3 miles of city halls produces equally interesting results. While these areas often overlap with the areas that were built up in 1960, they do not match directly as many downtowns had few residents in 1960 (look at the map of downtown Manhattan above, for example), and they often include communities outside of the city itself.

When looking at these neighborhoods, as shown in the following chart, the overall trend is negative: The preponderance of U.S. cities has lost a significant number of people within 1.5 miles of city hall and between 1.5 and 3 miles of city hall, with Philadelphia, Baltimore, New Orleans, and St. Louis leading the way.

There are some clear exceptions, however: San Jose, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Miami, Long Beach, Honolulu, Arlington, and Austin each grew dramatically within these core areas. New York City and Chicago grew dramatically (in fact, more than any other cities) very close to their city halls–but they also lost a significant number of people between 1.5 miles and 3 miles of downtown.

It is worth pointing out that these trends have changed over time and that choosing a starting point in 1960 was an arbitrary choice based on the availability of Census tract-level data for that year.

As the following graph illustrates, the population of the neighborhoods within 1.5 miles of city hall in the 100 largest cities has changed dramatically over time, and while the change from 1960 to 2014 is a key indicator, it is not all meaningful. Indeed, it is interesting to point out that of the areas within 1.5 miles of city hall of the 100 largest cities, only 5 grew between 1960 and 1970, but 6 grew between 1970 and 1980, 35 between 1980 and 1990, 51 between 1990 and 2000, and 53 between 2000 and 2014. In other words, while the central areas of most large cities are still less populated than they were in 1960, many have recovered a significant share of their population in the intervening years.

Diverging paths to growth

Of the 15 largest U.S. cities in 2014, 13 grew between 1960 and 2014. Yet of those 15, only 7 grew in the areas within 1.5 miles of city hall, and only 5 grew in their respective neighborhoods that were already built up in 1960. Even New York City, whose growth has been outpaced by just a few cities, has increased in population only in areas that were underdeveloped before from the perspective of residential occupancy, such as on Staten Island, in the financial district, and on land that was reclaimed from the rivers.

Los Angeles is an outlier, seeing stellar growth both overall and through infill development during this period.

Seen alternatively, examine the following chart illustrating how the 100 largest cities in 1960 have changed over time when separated by region (by chance, 1960’s 100 largest cities are roughly evenly distributed between the Midwest, Northeast, South, and West).

What’s intriguing is that though large cities in the South and West grew spectacularly over this period (the median city grew by more than 50 percent overall even as the median cities in the Midwest and Northeast lost people during that period), their infill development–particularly in the South–stalled out. Indeed, the median city in the South, much as in the Midwest, saw its 1960 developed areas decline in population by more than 40 percent; the median city in those two regions also experienced a decline in population in the 1.5 miles closest to city hall of more than 50 percent.

From the perspective of these alternative measurements, cities in the Northeast actually appear closer in trends to those in the West than those in the Midwest and South.

Implications for discussing population data

The U.S. has gained more than 140 million people since 1960, and the growth of its largest cities has at least to some degree corresponded to that; the total population of the 100 largest cities in 1960 grew from 47.5 million then to 57.4 million in 2014. Yet this growth has come largely through annexation and not through infill development or construction downtown, as I’ve noted above. This gives some clue as to why the country’s residents continue to rely on personal automobiles to get around. Overall, this paints a worrying picture about the renaissance that many cities appear to be going through; is it simply a blip on the overall continued suburbanization of the country?

Yet by evaluating growth from a different perspective using the indicators I presented above (surely there are other measures that would also be helpful) suggests that we need a more nuanced look at population growth. It is simultaneously true that Chicago lost the country’s second-largest number of inhabitants between 1960 and 2014 and that the same city gained the second-largest number of inhabitants living within 1.5 miles of city hall. It is simultaneously true that San Antonio gained almost 800,000 people in the city as a whole even as it lost more than 100,000 people in the areas that were already developed in 1960.

Why take these alternative measures of city growth so seriously? They should help us question whether the cities that grew fastest from 1960 to 2014 were Las Vegas, San Jose, and Austin or, alternatively, Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Miami or perhaps New York City, Chicago, and Honolulu. Each tells a different but useful tale about demographic change.

These measures might help us to understand, for example, how it is possible for half-vacant neighborhoods to exist just blocks from central Houston, which is otherwise booming. Or it may help us to understand why that city’s transit ridership has increased by just 5 percent since 1996 even though the city has grown by more than 25 percent since then. And they might help us get a better idea of what cities are truly regenerating their inner-city neighborhoods versus those that are simply gobbling up suburban growth to feed into their growing population counts.

Much of the rhetoric in the urban planning discourse over the past few years has focused on the lack of adequate housing construction in many of our cities’ most-desired communities. This is, no doubt, one of the most pressing issues facing places where supply has not kept up with demand and, as a result, rents have risen out of control.

Cities like San Francisco, notably, are frequently cited for inappropriately preventing growth, whereas places like Houston have been lauded for their unbelievable growth. Yet the data presented above should make us question this argument, or at least make us evaluate whether it conclusions correspond to actual demographic change. How is it that “growing” Houston lost almost 120,000 people in its neighborhoods that were already developed in 1960, while “growth-inhibiting” San Francisco gained more than 70,000 in its similar communities? Context matters.

* I used this density measure because it approximates mid-level suburban density levels.

Image at top: Construction in Los Angeles, from Flickr user fliegender (cc)

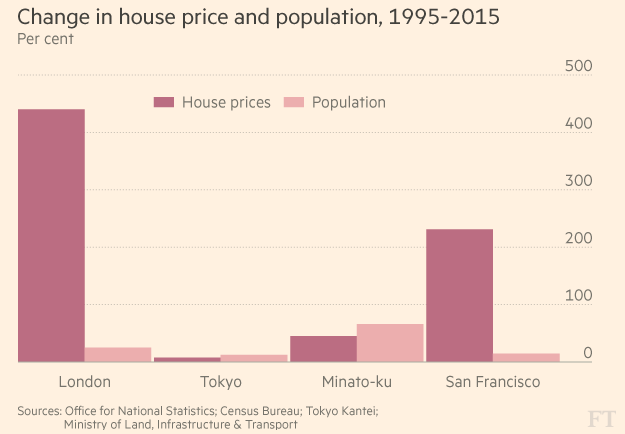

Here is a startling fact: in 2014 there were 142,417 housing starts in the city of Tokyo (population 13.3m, no empty land), more than the 83,657 housing permits issued in the state of California (population 38.7m), or the 137,010 houses started in the entire country of England (population 54.3m).

Here is a startling fact: in 2014 there were 142,417 housing starts in the city of Tokyo (population 13.3m, no empty land), more than the 83,657 housing permits issued in the state of California (population 38.7m), or the 137,010 houses started in the entire country of England (population 54.3m).

Greg Schoen

Greg Schoen Greg Schoen

Greg Schoen

Greg Schoen

Greg Schoen

Greg Schoen

Greg Schoen

REUTERS/Tim Wimborne

REUTERS/Tim Wimborne REUTERS/Tim Wimborne

REUTERS/Tim Wimborne REUTERS/Tim Wimborne

REUTERS/Tim Wimborne REUTERS/Tim Wimborne

REUTERS/Tim Wimborne REUTERS/Tim Wimborne

REUTERS/Tim Wimborne REUTERS/Tim Wimborne

REUTERS/Tim Wimborne

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5895887/labyrinth1.gif)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6589203/grolar-pizzly.gif) Grist/

Grist//cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6589217/spinged-rotted.gif) Grist/

Grist//cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6589241/narluga-beluwhal.gif) Grist/

Grist/

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6591957/GettyImages-89217709.jpg) Luciana Whitaker/Getty Images

Luciana Whitaker/Getty Images

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6591981/shutterstock_144478324.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6592011/shutterstock_404109046.jpg)