Jdenavascues

Shared posts

Growing Brain Cancer in Petri Dishes

Los impuros

No puedo contenerme ahora mismo. No quiero. Acabo de ver una foto de Juan Marsé cruzada por un letrero escalofriante en catalán: Renegado. Su cara noble como de boxeador viejo en primer plano, y esa palabra siniestra, esa acusación, ese estigma. Juan Marsé es un renegado por decir aquello que lleva diciendo desde hace más de medio siglo: lo que le da la gana. De muy joven Marsé empezó a escribir novelas que rompían con furia y belleza el sopor policial del franquismo. Fue el cronista de la Barcelona de las periferias emigrantes y de los barrios burgueses, con una ambición abarcadora de novelista francés del XIX. Su primera obra maestra Últimas tardes con Teresa , estaba llena de citas de Stendhal y de El rojo y el negro: Manolo el Pijoaparte era un trepador empujado por el instinto y el rencor de clase, como Julien Sorel, con un fondo suburbial y felino de rumba catalana. Marsé ha escrito y dicho lo que le da la gana hasta el punto de que su novela más grande, Si te dicen que caí, la publicó en México en 1973 para no someterse a las censuras y las autocensuras inevitables en España. Cuando se publicó aquí, en 1977, nos estallaba en las manos a quienes queríamos ser escritores, contar el mundo cercano y al mismo tiempo construir edificios luminosos de literatura. La libertad con la que había sido escrita esa novela era el anticipo de la que nosotros mismos queríamos ejercer en la literatura y en la vida. Marsé escribía un castellano tan libre porque era para él una lengua fronteriza, entrecruzada con el catalán, empapada de él. Marsé es un hombre íntegro, sentimental y huraño que puede enfadarse mucho, y lo ha hecho muchas veces, incluso con gran escándalo público.

Ahora los patriotas del banderazo y la hoguera han decidido señalarlo con lo que para ellos es el peor de los insultos: renegado. Un renegado es peor que un extranjero, porque a su alevosía une la condición de traidor. Los héroes de la libertad de los pueblos no sienten el menor interés por la libertad de las personas. Los pueblos son abstracciones a las que se puede atribuir cualquier virtud y hasta cualquier impulso de ira justiciera. Para mantener siempre su pureza necesitan enemigos exteriores y chivos expiatorios. Cualquier sátrapa y cualquier aspirante a comisario político puede ejercer con éxito la ventriloquía patriótica o justiciera y presentarse como portavoz del pueblo. Las personas concretas tienen una cara, una voz, una voluntad soberana o caprichosa. También tienen domicilio, y número de teléfono. Si las señalan son muy vulnerables. Algunas tienen trabajos y corren el peligro de perderlos. Juan Marsé fue un resistente contra la dictadura y es uno de los grandes escritores de España y de Cataluña, pero ahora resulta, a los ochenta y tantos años, que es un renegado. La foto de un renegado se puede quemar. También puede servir para acosarlo.

Se trata de una figura muy útil. Las democracias se hacen con ciudadanos. Las patrias viscerales necesitan extranjeros, enemigos, traidores, apóstatas. Renegados. Nada define mejor a una patria que la designación de un enemigo. Cuando era joven, Juan Marsé formó parte de lo que los franquistas llamaban la anti-España. Ahora lo han arrojado a la anti-Cataluña, en compañía , entre otros, de enemigos como Antonio Machado, Goya, Calderón, Negrín…

Todo esto es de una inmensa tristeza, de un aburrimiento insufrible.

The Digital Cell

If you are a cell biologist, you will have noticed the change in emphasis in our field.

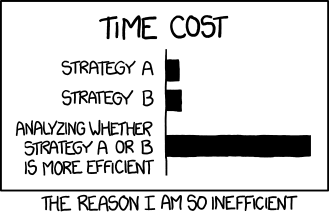

At one time, cell biology papers were – in the main – qualitative. Micrographs of “representative cells”, western blots of a “typical experiment”… This descriptive style gave way to more quantitative approaches, converting observations into numbers that could be objectively assessed. More recently, as technology advanced, computing power increased and data sets became more complex, we have seen larger scale analysis, modelling, and automation begin to take centre stage.

This change in emphasis encompasses several areas including (in no particular order):

- Statistical analysis

- Image analysis

- Programming

- Automation allowing analysis at scale

- Reproducibility

- Version control

- Data storage, archiving and accessing large datasets

- Electronic lab notebooks

- Computer vision and machine learning

- Prospective and retrospective modelling

- Mathematics and physics

The application of these areas is not new to biology and has been worked on extensively for years in certain areas. Perhaps most obviously by groups that identified themselves as “systems biologists”, “computational biologists”, and people working on large-scale cell biology projects. My feeling is that these methods have now permeated mainstream (read: small-scale) cell biology to such an extent that any groups that want to do cell biology in the future have to adapt in order to survive. It will change the skills that we look for when recruiting and it will shape the cell biologists of the future. Other fields such as biophysics and neuroscience are further through this change, while others have yet to begin. It is an exciting time to be a biologist.

I’m planning to post occasionally about the way that our cell biology research group is working on these issues: our solutions and our problems.

—

Part of a series on the future of cell biology in quantitative terms.

Mathematics, the language of nature. What are you sinking about?

|

| Swedish alphabet. Note lack of W. [Source] |

“I was always bad at math” is an excuse I have heard many of my colleagues complain about. I’m reluctant to join their complaints. I’ve been living in Sweden for four years now and still don’t speak Swedish. If somebody asks me, I’ll say I was always bad with languages. So who am I to judge people for not wanting to make an effort with math?

People don’t learn math for the same reason I haven’t learned Swedish: They don’t need it. It’s a fact that my complaining colleagues are tiptoeing around but I think we’d better acknowledge it if we ever want to raise mathematic literacy.Sweden is very welcoming to immigrants and almost everybody happily speaks English with me, often so well that I can’t tell if they’re native Swedes or Brits. At my workplace, the default language is English, both written and spoken. I have neither the exposure, nor the need, nor the use for Swedish. As a theoretical physicist, I have plenty of need for and exposure to math. But most people don’t.

The NYT recently collected opinions on how to make math and science relevant to “more than just geeks,” and Kimberly Brenneman, Director of the Early Childhood STEM Lab at Rutgers, informs us that

“My STEM education colleagues like to point out that few adults would happily admit to not being able to read, but these same people have no trouble saying they’re bad at math.”I like to point out it’s more surprising they like to point this out than this being the case. Life is extremely difficult when one can’t read neither manuals, nor bills, nor all the forms and documents that are sometimes mistaken for hallmarks of civilization. Not being able to read is such a disadvantage that it makes people wonder what’s wrong with you. But besides the basics that come in handy to decipher the fine print on your contracts, math is relevant only to specific professions.

I am lying of course when I say I was always bad with languages. I was bad with French and Latin and as my teachers told me often enough, that was sheer laziness. Je sais, tu sais, nous savons - Why make the effort? I never wanted to move to France. I learned English just fine: it was useful and I heard it frequently. And while my active Swedish vocabulary never proceeded beyond the very basics, I quickly learned Swedish to the extent that I need it. For all these insurance forms and other hallmarks of civilization, to read product labels, street signs and parking tickets (working on it).

I think that most people are also lying when they say they were always bad at math. They most likely weren’t bad, they were just lazy, never made an effort and got away with it, just as I did with my spotty Latin. The human brain is energetically highly efficient, but the downside is the inertia we feel when having to learn something new, the inertia that’s asking “Is it worth it? Wouldn’t I be better off hitting on that guy because he looks like he’ll be able to bring home food for a family?”

But mathematics isn’t the language of a Northern European country with a population less than that of other countries’ cities. Mathematics is the language of nature. You can move out of Sweden, but you can’t move out of the universe. And much like one can’t truly understand the culture of a nation without knowing the words at the basis of their literature and lyrics, one can’t truly understand the world without knowing mathematics.

Almost everybody uses some math intuitively. Elementary logic, statistics, and extrapolations are to some extent hardwired in our brains. Beyond that it takes some effort, yes. The reward for this effort is the ability to see the manifold ways in which natural phenomena are related, how complexity arises from simplicity, and the tempting beauty of unifying frameworks. It’s more than worth the effort.

One should make a distinction here between reading and speaking mathematics.

If you work in a profession that uses math productively or creatively, you need to speak math. But for the sake of understanding, being able to read math is sufficient. It’s the difference between knowing the meaning of a differential equation, and being able to derive and solve it. It’s the difference between understanding the relevance of a theorem, and leading the proof. I believe that the ability to ‘read’ math alone would enrich almost everybody’s life and it would also benefit scientific literacy generally.

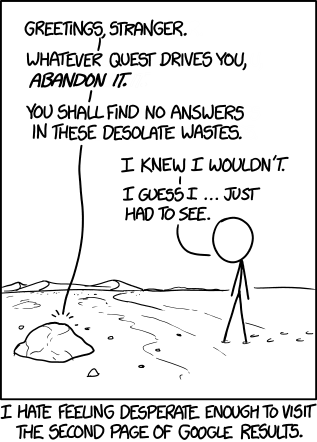

So needless to say, I am supportive of attempts to raise interest in math. I am just reluctant to join complaints about the bad-at-math excuse because this discussion more often than not leaves aside that people aren’t interested because it’s not relevant to them. And that what is relevant to them most mathematicians wouldn’t even call math. Without addressing this point, we’ll never convince anybody to make the effort to decipher a differential equation.

But of course people learn all the time things they don’t need! They learn to dance Gangnam style, speak Sindarin, or memorize the cast of Harry Potter. They do this because the cultural context is present. Their knowledge is useful for social reasons. And that is why I think to raise mathematic literacy the most important points are:

Exposure

Popular science writing rarely if ever uses any math. I want to see the central equations and variables. It’s not only that metaphors and analogies inevitably have shortcomings, but more importantly it’s that the reader gets away with the idea that one doesn’t actually need all these complicated equations. It’s a slippery slope that leads to the question what we need all these physicists for anyway. The more often you see something, the more likely you are to think and talk about it. That’s why we’re flooded with frequently nonsensical adverts that communicate little more than a brand name, and that’s why just showing people the math would work towards mathematic literacy.

I would also really like to see more math in news items generally. If experts are discussing what they learned from the debris of a plane crash, I would be curious to hear what they did. Not in great detail, but just to get a general idea. I want to know how the number quoted for energy return on investment was calculated, and I want to know how they arrived at the projected carbon capture rate. I want to see a public discussion of the Stiglitz theorem. I want people to know just how often math plays a role for what shapes their life and the lives of those who will come after us.

Don’t tell me it’s too complicated and people won’t understand it and it’s too many technical terms and, yikes, it won’t sell. Look at the financial part of a newspaper. How many people really understand all the terms and details, all the graphs and stats? And does that prevent them from having passionate discussions about the stock market? No, it doesn’t. Because if you’ve seen and heard it sufficiently often, the new becomes familiar, and people talk about what they see.

Culture

We don’t talk about math enough. The residue theorem in complex analysis is one of my favorite theorems. But I’m far more likely to have a discussion about the greatest songs of the 60s than about the greatest theorems of the 19th century. (Sympathy for the devil.) The origin of this problem is lack of exposure, but even with the exposure people still need the social context to put their knowledge to use. So by all means, talk about math if you can and tell us what you’re sinking about!

Escrito en tren

Un casi primo, compañero de escuela y amigo de la infancia, el profesor Juan Muñoz Madrid, me invitó a dar una charla en la universidad de Murcia. Juan es catedrático de Física. Llevábamos más de veinte años sin vernos. Pero allí estaba, a la salida del tren, con su cara inconfundible, idéntica a la que tenía cuando era un niño y le llamábamos de apodo “cartero”, porque su padre lo era. Me pidió que viniera a hablar de las relaciones entre las ciencias y las humanidades, en un encuentro sobre Física. Yo estaba felizmente retirado de actividades públicas desde la sobredosis asturiana, pero me apetecía ver a Juan y darle un abrazo. Ha sido ir y volver, pero ha valido la pena. Hemos charlado de ciencias y letras, nos hemos acordado de nuestra escuela y nuestro instituto San Juan de la Cruz, que fue tan decisivo para tantas personas de nuestra generación. Desde allí, con becas, con mucho esfuerzo, nos fue posible dar el salto hacia porvenires que habían sido rigurosamente inaccesibles para nuestros padres.

Y precisamente hoy leemos en el periódico que en España la palanca de ascenso social de la educación se ha detenido. Una vez más, los hijos de los privilegiados están destinados al privilegio, y los pobres a seguir siendo pobres. Da una tristeza inmensa. Cuántas vocaciones se estarán perdiendo o frustrando, cuántas capacidades no llegarán a revelarse nunca. Me despido de Juan y de su mujer, Marta, en el vestíbulo de la estación, hace una media hora. Ella es también profesora de Física. Hago el recuento de nuestros orígenes: un hijo de hortelano, una hija de confitero en Getafe, un hijo de cartero. Sin una enseñanza rigurosa, sin un compromiso público verdadero, sin padres que asuman con entusiasmo y exigencia la educación de sus hijos, sin una política justa de becas, no hay posibilidad de justicia.

Mientras tanto, seguimos con la murga de las identidades.

Il Gruffalo

Il Gruffalo

English version by Julia Donaldson

Tradotto in Italiano da Giorgio Gilestro

Un topolino andò passeggiando per il bosco buio e pauroso

Una volpe vide il topino, che le sembrò così appetitoso

“Dove stai andando, piccolo topino?

Vieni a casa mia, che ci facciamo uno spuntino”.

“É molto gentile da parte tua, cara volpe, ma no –

Sto andando a fare pranzo con un Gruffalo”

“Un Gruffalo? E che cosa sarà mai?”

“Un Gruffalo: che non lo sai?

Ha terribili zanne

unghie storte e paurose,

e terribili denti tra le fauci pelose”

“E dove vi incontrate?”

Proprio qui, in questo posto,

e il suo cibo preferito é volpe arrosto!”

“Volpe arrosto!” La volpe urlò,

“Ti saluto, topolino” e se la filò.

“Stupida volpe! Non ci é arrivata?

Questa storia del Gruffalo, me la sono inventata!”

Continuò il topino per il bosco pauroso,

un gufo adocchiò il topo, che gli sembrò così appetitoso.

“Dove stai andando, delizioso topetto?

Vieni a prenderti un tè sopra l’albero, nel mio buchetto”

“É paurosamente gentile da parte tua, Gufo, ma no –

Il tè lo vado a prendere col Gruffalo”

“Il Gruffalo? E che cosa é mai?”

“Un Gruffalo: che non lo sai?

Ha ginocchia sbilenche,

e unghione paurose,

e sulla punta del naso, pustole velenose”

“E dove lo incontri?”

“Al ruscello, lì sul lato,

E il suo cibo preferito é gufo con gelato”

“Gufo e gelato?” Guuguu, guugoo.

Ti saluto topino!” e il gufò arruffato decollò.

“Stupido gufo! Non ci é arrivato?

Il racconto del Gruffalo, me lo sono inventato!”

Il topino continuò per il bosco pauroso,

Un serpente lo vide, é gli sembrò così appettitoso.

“Dove stai andando, piccolo topino?

Viene a un banchetto con me, in quell’angolino.”

“É terribilmente gentile da parte tua, serpente, ma no –

Al banchetto ci vado col Gruffalo!”

“Il Gruffalo? E cosa é mai?”

“Un Gruffalo! Che non lo sai?

Ha occhi arancioni,

e lingua nera e scura,

e sulla schiena: aculei violacei che fanno paura”

“Dove lo incontri?”

“Qui, al laghetto incantato,

e il suo cibo preferito é serpente strapazzato.”

“Serpente strapazzato? Lascio la scia!

Ciao ciao topolino” e il serpente scivolò via.

“Stupido serpente! Non l’ha capito?

Questo affare del Gruffalo me lo sono inventa….

TOOOOO!”

Ma chi é questo mostro

con terribili zanne

e unghie paurose,

e terribili denti tra lefauci pelose.

Ha ginocchia sbilenche,

e unghione paurose,

e sulla punta del naso, pustolone velenose.

Occhi arancioni,

e lingua nera e scura,

e sulla schiena: aculei violacei che fanno paura”

“Oh, Aiuto! Oh no!

Non é un semplice mostro: é il Gruffalo!”

“Il mio cibo preferito!” Disse il Gruffalo affamato,

“Sarai delizioso, sul pane imburrato!”

“Delizioso?” Disse il topino. “Non lo direi al tuo posto!”

Sono l’esserino più pauroso di tutto il bosco.

Passeggiamo un po’ e ti farò vedere,

come tutti gli animali corrono quando mi vedono arrivare!

“Va bene!” disse il Gruffalo esplodendo in un risatone tetro,

“Tu vai avanti che io ti vengo dietro”.

Caminnarono e camminarono, finchè il Gruffalo ammonì:

“sento come un sibilo tra quel fogliame lì”.

“É il serpente!” disse il topo “Ciao Serpente, ben trovato!”

Serpente sbarrò gli occhi e guardò il Gruffalo, imbambolato.

“Accipicchia!” disse, “Ciao ciao topolino!”

E veloce si infilò nel suo rifugino.

“Vedi”, disse il topo. “Che ti ho detto?”

“Incredibile!”, esclamò il Gruffalo esterefatto.

Camminarono ancora un po’, finchè il Gruffalo ammonì:

“sento come un fischio tra quegli alberi li’”.

“É il Gufo”, disse il topo “Ciao Gufo, ben trovato!”

Gufo sbarrò gli occhi e guardò il Gruffalo, imbabolato.

“Cavoletti!” disse “Ciao ciao topolino!”

E veloce volò via nel suo rifugino.

“Vedi?”, disse il topo. “Che ti ho detto?”

“Sbalorditivo”, esclamò il Gruffalo esterefatto.

Camminarono ancora un po’, finchè il Gruffalo ammonì:

“sento come dei passi in quel sentiero li’”.

“É Volpe”, disse il topo “Ciao Volpe, ben trovata!”

Volpe sbarrò gli occhi e guardò il Gruffalo, imbabolata.

“Aiuto!” disse, “Ciao ciao topolino!”

E come una saetta corse nel suo rifugino.

“Allora, Gruffalo”, disse il topo. “Sei convinto ora, eh’?

Hanno tutti paura e terrore di me!

Ma sai una cosa? Ora ho fame e la mia pancia borbotta.

Il mio cibo preferito é: pasta Gruffalo e ricotta!”

“Gruffalo e ricotta?!” Il Gruffalo urlò,

e veloce come il vento se la filò.

Tutto era calmo nel bosco buio e pauroso.

Il topino trovò un nocciolo: che era tanto tanto appetitoso.

Pietro loves the Gruffalo. He likes to alternate the original English version to a customized Italian one, so I came up with this translation. Only once I completed the translation, did I realize that an official Italian version was actually on sale. It’s titled “A spasso col mostro” and can be read here. I like mine better of course.