The first video game was a 1952 research product called OXO — tic-tac-toe played on a computer the size of a large room:

Fifteen years later Ralph Baer produced “The Brown Box”; Magnavox licensed Baer’s device and released it as the Odyssey five years later — it was the first home video game console:

The Odyssey made Magnavox a lot of money, but not through direct sales: the company sued Atari for ripping off one of the Odyssey’s games to make “Pong”, the company’s first arcade game and, in 1975, first home video game, eventually reaping over $100 million in royalties and damages. In other words, arguments about IP and control have been part of the industry from the beginning.

In 1977 Atari released the 2600, the first console I ever owned:1

All of the games for the Atari were made by Atari, because of course they were; IBM had unbundled mainframe software and hardware in 1969 in an (unsuccessful) attempt to head off an antitrust case, but video games barely existed as a category in 1977. Indeed, it was only four years earlier when Steve Wozniak had partnered with Steve Jobs to design a circuit board for Atari’s Breakout arcade game; this story is most well-known for the fact that Jobs lied to Wozniak about the size of the bonus he earned, but the pertinent bit for this Article is that video game development was at this point intrinsically tied to hardware.

That, though, was why the 2600 was so unique: games were not tied to hardware but rather self-contained in cartridges, meaning players would use the same system to play a whole bunch of different games:

The implications of this separation did not resonate within Atari, which had been sold by founder Nolan Bushnell to Warner Communications in 1976, in an effort to get the 2600 out the door. Game Informer explains what happened:

In early 1979, Atari’s marketing department issued a memo to its programing staff that listed all the games Atari had sold the previous year. The list detailed the percentage of sales each game had contributed to the company’s overall profits. The purpose of the memo was to show the design team what kinds of games were selling and to inspire them to create more titles of a similar breed…David Crane, Larry Kaplan, Alan Miller, and Bob Whitehead were four of Atari’s superstar programmers. Collectively, the group had been responsible for producing many of Atari’s most critical hits…

“I remember looking at that memo with those other guys,” recalls Crane, “and we realized that we had been responsible for 60 percent of Atari’s sales in the previous year – the four of us. There were 35 people in the department, but the four of us were responsible for 60 percent of the sales. Then we found another announcement that [Atari] had done $100 million in cartridge sales the previous year, so that 60 percent translated into $60 million.”

These four men may have produced $60 million in profit, but they were only making about $22,000 a year. To them, the numbers seemed astronomically disproportionate. Part of the problem was that when the video game industry was founded, it had molded itself after the toy industry, where a designer was paid a fixed salary and everything that designer produced was wholly owned by the company. Crane, Kaplan, Miller, and Whitehead thought the video game industry should function more like the book, music, or film industries, where the creative talent behind a project got a larger share of the profits based on its success.

The four walked into the office of Atari CEO Ray Kassar and laid out their argument for programmer royalties. Atari was making a lot of money, but those without a corner office weren’t getting to share the wealth. Kassar – who had been installed as Atari’s CEO by parent company Warner Communications – felt obligated to keep production costs as low as possible. Warner was a massive corporation and everyone helped contribute to the company’s success. “He told us, ‘You’re no more important to those projects than the person on the assembly line who put them together. Without them, your games wouldn’t have sold anything,’” Crane remembers. “He was trying to create this corporate line that it was all of us working together that make games happen. But these were creative works, these were authorships, and he didn’t get it.”

“Kassar called us towel designers,” Kaplan told InfoWorld magazine back in 1983, “He said, ‘I’ve dealt with your kind before. You’re a dime a dozen. You’re not unique. Anybody can do a cartridge.’”

That “anyone” included the so-called “Gang of Four”, who decided to leave Atari and form the first 3rd-party video game company; they called it Activision.

3rd-Party Software

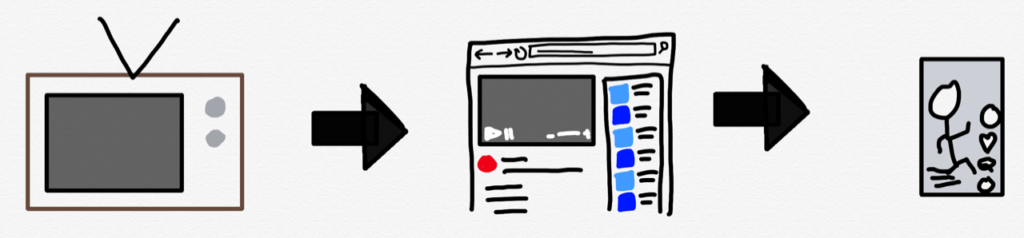

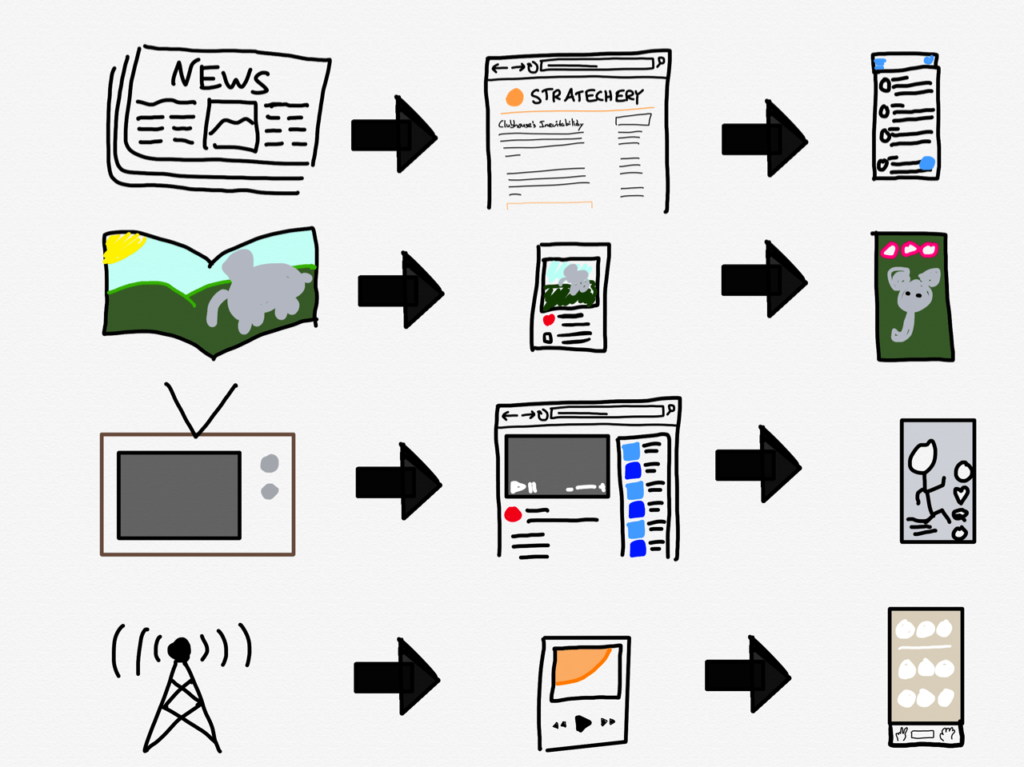

Activision represented the first major restructuring of the video game value chain; Steve Wozniak’s Breakout was fully integrated in terms of hardware and software:

The Atari 2600 with its cartridge-based system modularized hardware and software:2

Activision took that modularization to its logical (and yet, at the time, unprecedented) extension, by being a different company than the one that made the hardware:

Activision, which had struggled to raise money given the fact it was targeting a market that didn’t yet exist, and which faced immediate lawsuits from Atari, was a tremendous success; now venture capital was eager to fund the market, leading to a host of 3rd-party developers, few of whom had the expertise or skill of Activision. The result was a flood of poor quality games that soured consumers on the entire market, leading to the legendary video game crash of 1983: industry revenue plummeted from $3.2 billion in 1983 to a mere $100 million in 1985. Activision survived, but only by pivoting to making games for the nascent personal computing market.

The personal computer market was modular from the start, and not just in terms of software. Compaq’s success in reverse-engineering the IBM PC’s BIOS created a market for PC-compatible computers, all of which ran the increasingly ubiquitous Microsoft operating system (first DOS, then Windows). This meant that developers like Activision could target Windows and benefit from competition in the underlying hardware.

Moreover, there were so many more use cases for the personal computer, along with a burgeoning market in consumer-focused magazines that reviewed software, that the market was more insulated from the anarchy that all but destroyed the home console market.

That market saw a rebirth with Nintendo’s Famicom system, christened the “Nintendo Entertainment System” for the U.S. market (Nintendo didn’t want to call it a console to avoid any association with the 1983 crash, which devastated not just video game makers but also retailers). Nintendo created its own games like Super Mario Bros. and Zelda, but also implemented exacting standards for 3rd-party developers, requiring them to pass a battery of tests and pay a 30% licensing fee for a maximum of five games a year; only then could they receive a dedicated chip for their cartridge that allowed it to work in the NES.

Nintendo’s firm control of the third-party developer market may look familiar: it was an early precedent for the App Store battles of the last decade. Many of the same principles were in play:

- Nintendo had a legitimate interest in ensuring quality, not simply for its own sake but also on behalf of the industry as a whole; similarly, the App Store, following as it did years of malware and viruses in the PC space, restored customer confidence in downloading third-party software.

- It was Nintendo that created the 30% share for the platform owner that all future console owners would implement, and which Apple would set as the standard for the App Store.

- While Apple’s App Store lockdown is rooted in software, Nintendo had the same problem that Atari had in terms of the physical separation of hardware and software; this was overcome by the aforementioned lockout chips, along with branding the Nintendo “Seal of Quality” in an attempt to fight counterfeit lockout chips.

Nintendo’s strategy worked, but it came with long-term costs: developers, particularly in North America, hated the company’s restrictions, and were eager to support a challenger; said challenger arrived in the form of the Sega Genesis, which launched in the U.S. in 1989. Sega initially followed Nintendo’s model of tight control, but Electronic Arts reverse-engineered Sega’s system, and threatened to create their own rival licensing program for the Genesis if Sega didn’t dramatically loosen their controls and lower their royalties; Sega acquiesced and went on to fight the Super Nintendo, which arrived in the U.S. in 1991, to a draw, thanks in part to a larger library of third-party games.

Sony’s Emergence

The company that truly took the opposite approach to Nintendo was Sony; after being spurned by Nintendo in humiliating fashion — Sony announced the Play Station CD-ROM add-on at CES in 1991, only for Nintendo to abandon the project the next day — the electronics giant set out to create their own console which would focus on 3D-graphics and package games on CD-ROMs instead of cartridges. The problem was that Sony wasn’t a game developer, so it started out completely dependent on 3rd-party developers.

One of the first ways that Sony addressed this was by building an early partnership with Namco, Sega’s biggest rival in terms of arcade games. Coin-operated arcade games were still a major market in the 1990s, with more revenue than the home market for the first half of the decade. Arcade games had superior graphics and control systems, and were where new games launched first; the eventual console port was always an imitation of the original. The problem, however, is that it was becoming increasingly expensive to build new arcade hardware, so Sony proposed a partnership: Namco could use modified PlayStation hardware as the basis of its System 11 arcade hardware, which would make it easy to port its games to PlayStation. Namco, which also rebuilt its more powerful Ridge Racer arcade game for the PlayStation, took Sony’s offer: Ridge Racer launched with the Playstation, and Tekken was a massive hit given its near perfect fidelity to the arcade version.

Sony was much better for 3rd-party developers in other ways, as well: while the company maintained a licensing program, its royalty rates were significantly lower than Nintendo’s, and the cost of manufacturing CD-ROMs was much lower than manufacturing cartridges; this was a double whammy for the Nintendo 64 because while cartridges were faster and offered the possibility of co-processor add-ons, what developers really wanted was the dramatically increased amount of storage CD-ROMs afforded. The Playstation was also the first console to enable development on the PC in a language (C) that was well-known to existing developers. In the end, despite the fact that the Nintendo 64 had more capable hardware than the PlayStation, it was the PlayStation that won the generation thanks to a dramatically larger game library, the vast majority of which were third-party games.

Sony extended that advantage with the PlayStation 2, which was backwards compatible with the PlayStation, meaning it had a massive library of 3rd-party games immediately; the newly-launched Xbox, which was basically a PC, and thus easy to develop for, made a decent showing, while Nintendo struggled with the Gamecube, which had both a non-standard controller and non-standard microdisks that once again limited the amount of content relative to the DVDs used for PlayStation 2 and Xbox (and it couldn’t function as a DVD player, either).

This period for video games was the high point in terms of console competition for 3rd-party developers for two reasons:

- First, there were still meaningful choices to be made in terms of hardware and the overall development environment, as epitomized by Sony’s use of CD-ROMs instead of cartridges.

- Second, developers were still constrained by the cost of developing for distinct architectures, which meant it was important to make the right choice (which dramatically increased the return of developing for the same platform as everyone else).

It was the Sony-Namco partnership, though, that was a harbinger of the future: it behooved console makers to have similar hardware and software stacks to their competitors, so that developers would target them; developers, meanwhile, were devoting an increasing share of their budget to developing assets, particularly when the PS3/Xbox 360 generation targeted high definition, which increased their motivation to be on multiple platforms to better leverage their investments. It was Sony that missed this shift: the PS3 had a complicated Cell processor that was hard to develop for, and a high price thanks to its inclusion of a Blu-Ray player; the Xbox 360 had launched earlier with a simpler architecture, and most developers built for the Xbox first and Playstation 3 second (even if they launched at the same time).

The real shift, though, was the emergence of game engines as the dominant mode of development: instead of building a game for a specific console, it made much more sense to build a game for a specific engine which abstracted away the underlying hardware. Sometimes these game engines were internally developed — Activision launched its Call of Duty franchise in this time period (after emerging from bankruptcy under new CEO Bobby Kotick) — and sometimes they were licensed (i.e. Epic’s Unreal Engine). The impact, though, was in some respects similar to cartridges on the Atari 2600:

In this new world it was the consoles themselves that became modularized: consumers picked out their favorite and 3rd-party developers delivered their games on both.

Nintendo, meanwhile, dominated the generation with the Nintendo Wii. What was interesting, though, is that 3rd-party support for the Wii was still lacking, in part because of the underpowered hardware (in contrast to previous generations): the Wii sold well because of its unique control method — which most people used to play Wii Sports — and Nintendo’s first-party titles. It was, in many respects, Nintendo’s most vertically-integrated console yet, and was incredibly successful.

Sony Exclusives

Sony’s pivot after the (relatively) disappointing PlayStation 3 was brilliant: if the economic imperative for 3rd-party developers was to be on both Xbox and PlayStation (and the PC), and if game engines made that easy to implement, then there was no longer any differentiation to be had in catering to 3rd-party developers.

Instead Sony beefed up its internal game development studios and bought up several external ones, with the goal of creating PlayStation 4 exclusives. Now some portion of new games would not be available on Xbox not because it had crappy cartridges or underpowered graphics, but because Sony could decide to limit its profit on individual titles for the sake of the broader PlayStation 4 ecosystem. After all, there would still be a lot of 3rd-party developers; if Sony had more consoles than Microsoft because of its exclusives, then it would harvest more of those 3rd-party royalty fees.

Those fees, by the way, started to head back up, particularly for digital-only versions, which returned to that 30% cut that Nintendo had pioneered many years prior; this is the downside of depending on universal abstractions like game engines while bearing high development costs: you have no choice but to be on every platform no matter how much it costs.

Sony bet correctly: the PS4 dominated its generation, helped along by Microsoft making a bad bet of its own by packing in the Kinect with the Xbox One. It was a repeat of Sony’s mistake with the PS3, in that it was a misguided attempt to differentiate in hardware when the fundamental value chain had long since dictated that the console was increasingly a commodity. Content is what mattered — at least as long as the current business model persisted.

Nintendo, meanwhile, continued to march to its own vertically-integrated drum: after the disastrous Wii U the company quickly pivoted to the Nintendo Switch, which continues to leverage its truly unique portable form factor and Nintendo’s first-party games to huge sales. Third party support, though, remains extremely tepid; it’s just too underpowered, and the sort of person that cares about third-party titles like Madden or Call of Duty has long since bought a PlayStation or Xbox.

The FTC vs. Microsoft

Forty years of context may seem like overkill when it comes to examining the FTC’s attempt to block Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision, but I think it is essential for multiple reasons.

First, the video game market has proven to be extremely dynamic, particularly in terms of 3rd-party developers:

- Atari was vertically integrated

- Nintendo grew the market with strict control of 3rd-party developers

- Sony took over the market by catering to 3rd-party developers and differentiating on hardware

- Xbox’s best generation leaned into increased commodification and ease-of-development

- Sony retook the lead by leaning back into vertical integration

That is quite the round trip, and it’s worth pointing out that attempting to freeze the market in its current iteration at any point over the last forty years would have foreclosed future changes.

At the same time, Sony’s vertical integration seems more sustainable than Atari’s. First, Sony owns the developers who make the most compelling exclusives for its consoles; they can’t simply up-and-leave like the Gang of Four. Second, the costs of developing modern games has grown so high that any 3rd-party developer has no choice but to develop for all relevant consoles. That means that there will never be a competitor who wins by offering 3rd-party developers a better deal; the only way to fight back is to have developers of your own, or a completely different business model.

The first fear raised by the FTC is that Microsoft, by virtue of acquiring Activision, is looking to fight its own exclusive war, and at first blush it’s a reasonable concern. After all, Activision has some of the most popular 3rd-party games, particularly the aforementioned Call of Duty franchise. The problem with this reasoning, though, is that the price Microsoft paid for Activision was a multiple of Activision’s current revenues, which include billions of dollars for games sold on Playstation. To suddenly cut Call of Duty (or Activision’s other multi-platform titles) off from Playstation would be massively value destructive; no wonder Microsoft said it was happy to sign a 10-year deal with Sony to keep Call of Duty on PlayStation.

Just for clarity’s sake, the distinction here from Sony’s strategy is the fact that Microsoft is acquiring these assets. It’s one thing to develop a game for your own platform — you’re building the value yourself, and choosing to harvest it with an ecosystem strategy as opposed to maximizing that games’ profit. An acquirer, though, has to pay for the business model that already exists.

At the same time, though, it’s no surprise that Microsoft has taken in-development assets from its other acquisition like ZeniMax and made them exclusives; that is the Sony strategy, and Microsoft was very clear when it acquired ZeniMax that it would keep cross-platform games cross-platform but may pursue a different strategy for new intellectual property. CEO of Microsoft Gaming Phil Spencer told Bloomberg at the time:

In terms of other platforms, we’ll make a decision on a case-by-case basis.

Given this, it’s positively bizarre that the FTC also claims that Microsoft lied to the E.U. with regards to its promises surrounding the ZeniMax acquisition: the company was very clear that existing cross-platform games would stay cross-platform, and made no promises about future IP. Indeed, the FTC’s claims were so off-base that the European Commission felt the need to clarify that Microsoft didn’t mislead the E.U.; from Mlex:

Microsoft didn’t make any “commitments” to EU regulators not to release Xbox-exclusive content following its takeover of ZeniMax Media, the European Commission has said. US enforcers yesterday suggested that the US tech giant had misled the regulator in 2021 and cited that as a reason to challenge its proposed acquisition of Activision Blizzard. “The commission cleared the Microsoft/ZeniMax transaction unconditionally as it concluded that the transaction would not raise competition concerns,” the EU watchdog said in an emailed statement.

The absence of competition concerns “did not rely on any statements made by Microsoft about the future distribution strategy concerning ZeniMax’s games,” said the commission, which itself has opened an in-depth probe into the Activision Blizzard deal and appears keen to clarify what happened in the previous acquisition. The EU agency found that even if Microsoft were to restrict access to ZeniMax titles, it wouldn’t have a significant impact on competition because rivals wouldn’t be denied access to an “essential input,” and other consoles would still have a “large array” of attractive content.

The FTC’s concerns about future IP being exclusive ring a bit hypocritical given the fact that Sony has been pursuing the exact same strategy — including multiple acquisitions — without any sort of regulatory interference; more than that, though, to effectively make up a crime is disquieting. To be fair, those Sony acquisitions were a lot smaller than Activision, but this goes back to the first point: the entire reason Activision is expensive is because of its already-in-market titles, which Microsoft has every economic incentive to keep cross-platform (and which it is willing to commit to contractually).

Whither Competition

It’s the final FTC concern, though, that I think is dangerous. From the complaint:

These effects are likely to be felt throughout the video gaming industry. The Proposed Acquisition is reasonably likely to substantially lessen competition and/or tend to create a monopoly in both well-developed and new, burgeoning markets, including highperformance consoles, multi-game content library subscription services, and cloud gaming subscription services…

Multi-Game Content Library Subscription Services comprise a Relevant Market. The anticompetitive effects of the Proposed Acquisition also are reasonably likely to occur in any relevant antitrust market that contains Multi-Game Content Library Subscription Services, including a combined Multi-Game Content Library and Cloud Gaming Subscription Services market.

Cloud Gaming Subscription Services are a Relevant Market. The anticompetitive effects of the Proposed Acquisition alleged in this complaint are also likely to occur in any relevant antitrust market that contains Cloud Gaming Subscription Services, including a combined Multi-Game Content Library and Cloud Gaming Subscription Services market.

“Multi-Game Content Library Subscription Services” and “Cloud Gaming Subscription Services” are, indeed, the reason why Microsoft wants to do this deal. I explained the rationale when Microsoft acquired ZeniMax:

A huge amount of discussion around this acquisition was focused on Microsoft needing its own stable of exclusives in order to compete with Sony, but it’s important to note that making all of ZeniMax’s games exclusives would be hugely value destructive, at least in the short-to-medium term. Microsoft is paying $7.5 billion for a company that currently makes money selling games on PC, Xbox, and PS5, and simply cutting off one of those platforms — particularly when said platform is willing to pay extra for mere timed exclusives, not all-out exclusives — is to effectively throw a meaningful chunk of that value away. That certainly doesn’t fit with Nadella’s statement that “each layer has to stand on its own for what it brings”…

Microsoft isn’t necessarily buying ZeniMax to make its games exclusive, but rather to apply a new business model to them — specifically, the Xbox Game Pass subscription. This means that Microsoft could, if it chose, have its cake and eat it too: sell ZeniMax games at their usual $60~$70 price on PC, PS5, Xbox, etc., while also making them available from day one to Xbox Game Pass subscribers. It won’t take long for gamers to quickly do the math: $180/year — i.e. three games bought individually — gets you access to all of the games, and not just on one platform, but on all of them, from PC to console to phone.

Sure, some gamers will insist on doing things the old way, and that’s fine: Microsoft can make the same money ZeniMax would have as an independent company. Everyone else can buy into Microsoft’s model, taking advantage of the sort of win-win-win economics that characterize successful bundles. And, if they have a PS5 and thus can’t get access to Xbox Game Pass on their TVs, an Xbox is only an extra $10/month away.

Microsoft is willing to cannibalize itself to build a new business model for video games, and it’s a business model that is pretty darn attractive for consumers. It’s also a business model that Activision wouldn’t pursue on its own, because it has its own profits to protect. Most importantly, though, it’s a business model that is anathema to Sony: making titles broadly available to consumers on a subscription basis is the exact opposite of the company’s exclusive strategy, which is all about locking consumers into Sony’s platform.

Here’s the thing: isn’t this a textbook example of competition? The FTC is seeking to preserve a model of competition that was last relevant in the PS2/Xbox generation, but that plane of competition has long since disappeared. The console market as it is today is one that is increasingly boring for consumers, precisely because Sony has won. What is compelling about Microsoft’s approach is that they are making a bet that offering consumers a better deal is the best way to break up Sony’s dominance, and this is somehow a bad thing?

What makes this determination to outlaw future business models particularly frustrating is that the real threat to gaming today is the dominance of storefronts that exact their own tax while contributing nothing to the development of the industry. The App Store and Google Play leverage software to extract 30% from mobile games just because they can — and sure, go ahead and make the same case about Microsoft and Sony. If the FTC can’t be bothered to check the blatant self-favoring inherent in these models, at the minimum it seems reasonable to give a chance to a new kind of model that could actual push consumers to explore alternative ways to game on their devices.

For the record, I do believe this acquisition demands careful overview, and it’s completely appropriate to insist that Microsoft continue to deliver Activision titles to other platforms, even if it wouldn’t make economic sense to do anything but. It’s increasingly difficult, though, to grasp any sort of coherent theory to the FTC’s antitrust decisions beyond ‘big tech bad’. There are real antitrust issues in the industry, but that requires actually understanding the industry to tease them out; that sort of understanding applied to this case would highlight Sony’s actual dominance and that having multiple compelling platforms with different business models is the essence of competition.

The Chinese government has restricted video game access for younger players to one hour per day from Friday to Sunday. ...

The Chinese government has restricted video game access for younger players to one hour per day from Friday to Sunday. ... Valve boss Gabe Newell has indicated that finding the right price point for its new console, the Steam Deck, was a rather painful process. ...

Valve boss Gabe Newell has indicated that finding the right price point for its new console, the Steam Deck, was a rather painful process. ... "We wanted to simulate the familiar space of a commercial airliner, to create a genuine experience players can reflect on," says Hosni Auji, Lead Designer for Airplane Mode. ...

"We wanted to simulate the familiar space of a commercial airliner, to create a genuine experience players can reflect on," says Hosni Auji, Lead Designer for Airplane Mode. ...

The UK ad authority has put the kibosh on a certain format of ads used by Playrix, arguing that the ads for each wildly misrepresent the gameplay of each title. ...

The UK ad authority has put the kibosh on a certain format of ads used by Playrix, arguing that the ads for each wildly misrepresent the gameplay of each title. ... Nintendo has just announced Mario Kart Live: Home Circuit, a mixed reality Switch title that lets players build and race around real-world circuits using remote control karts. ...

Nintendo has just announced Mario Kart Live: Home Circuit, a mixed reality Switch title that lets players build and race around real-world circuits using remote control karts. ...

Jackbox Games CEO Mike Bilder joined us on the GDC Podcast to explain how his company is dealing with dramatic increases in traffic amid continuing stay at home orders in the time of COVID-19. ...

Jackbox Games CEO Mike Bilder joined us on the GDC Podcast to explain how his company is dealing with dramatic increases in traffic amid continuing stay at home orders in the time of COVID-19. ... Nintendo has a habit of launching fitness-focused games paired with new peripherals for its motion-control savvy systems, and the Nintendo Switch is no exception. ...

Nintendo has a habit of launching fitness-focused games paired with new peripherals for its motion-control savvy systems, and the Nintendo Switch is no exception. ...

It's interesting to see Nintendo and Twitch join forces for the promotion, and shows the Japanese console maker is searching for ways to maintain and stoke interest in its fledgling online service. ...

It's interesting to see Nintendo and Twitch join forces for the promotion, and shows the Japanese console maker is searching for ways to maintain and stoke interest in its fledgling online service. ... The study looked at data surrounding British teens and notes that, unlike previous research into the potential link, the hypothesis, methods, and analysis technique were publicly registered ahead of the actual research. ...

The study looked at data surrounding British teens and notes that, unlike previous research into the potential link, the hypothesis, methods, and analysis technique were publicly registered ahead of the actual research. ... Streaming mogul Netflix claims Fortnite is now a bigger competitor than other media companies like Game of Thrones and True Detective producer HBO. ...

Streaming mogul Netflix claims Fortnite is now a bigger competitor than other media companies like Game of Thrones and True Detective producer HBO. ... According to Rockstar, it's a figure that means the game has achieved the "single biggest opening weekend in the history of entertainment." ...

According to Rockstar, it's a figure that means the game has achieved the "single biggest opening weekend in the history of entertainment." ... Sony has revealed the full list of retro games that'll be crammed onto the PlayStation Classic when it launches this December. ...

Sony has revealed the full list of retro games that'll be crammed onto the PlayStation Classic when it launches this December. ...