The shamelessness was breathtaking.

Having told a few jokes, summarized his manifesto, and acknowledged the victim of the so-called “Facebook-killer” in Cleveland, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg opened his keynote presentation at the company’s F8 developer conference like this:

You may have noticed that we rolled out some cameras across our apps recently. That was Act One. Photos and videos are becoming more central to how we share than text. So the camera needs to be more central than the text box in all of our apps. Today we’re going to talk about Act Two, and where we go from here, and it’s tied to this broader technological trend that we’ve talked about before: augmented reality.

If that seems familiar, it’s because it is the Explain Like I’m Five summary of Snap’s S-1:

In the way that the flashing cursor became the starting point for most products on desktop computers, we believe that the camera screen will be the starting point for most products on smartphones. This is because images created by smartphone cameras contain more context and richer information than other forms of input like text entered on a keyboard. This means that we are willing to take risks in an attempt to create innovative and different camera products that are better able to reflect and improve our life experiences.

Snap may have declared itself a camera company; Zuckerberg dismissed it as “Act One”, making it clear that Facebook intended to not simply adopt one of Snapchat’s headline features but its entire vision.

Facebook and Microsoft

Shortly after Snap’s S-1 came out, I wrote in Snap’s Apple Strategy that the company was like Apple; unfortunately, the Apple I was referring to was not the iPhone-making juggernaut we are familiar with today, but rather the Macintosh-creating weakling that was smushed by Microsoft, which is where Facebook comes in.

Today, if Snap is Apple, then Facebook is Microsoft. Just as Microsoft succeeded not because of product superiority but by leveraging the opportunity presented by the IBM PC, riding Big Blue’s coattails to ecosystem dominance, Facebook has succeeded not just on product features but by digitizing offline relationships, leveraging the desire of people everywhere to connect with friends and family. And, much like Microsoft vis-à-vis Apple, Facebook has had The Audacity of Copying Well.

I wrote The Audacity of Copying Well when Instagram launched Instagram stories; what was brilliant about the product is that Facebook didn’t try to re-invent the wheel. Instagram Stories — and now Facebook Stories and WhatsApp Stories and Messenger Day — are straight rip-offs of Snapchat Stories, which is not only not a problem, it’s actually the exact optimal strategy: Instagram’s point of differentiation was not features, but rather its network. By making Instagram Stories identical to Snapchat Stories, Facebook reduced the competition to who had the stronger network, and it worked.

Microsoft and Monopoly

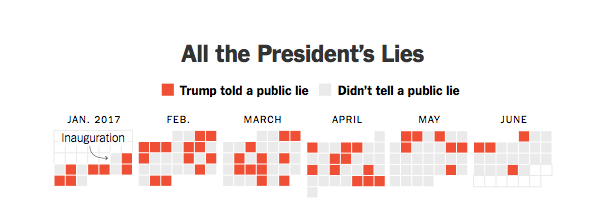

Microsoft, of course, was found to be a monopoly, and, as I wrote a couple of months ago in Manifestos and Monopolies, it is increasingly difficult to not think the same about Facebook. That, though, is exactly what you would expect for an aggregator. From Antitrust and Aggregation:

The first key antitrust implication of Aggregation Theory is that, thanks to these virtuous cycles, the big get bigger; indeed, all things being equal the equilibrium state in a market covered by Aggregation Theory is monopoly: one aggregator that has captured all of the consumers and all of the suppliers. This monopoly, though, is a lot different than the monopolies of yesteryear: aggregators aren’t limiting consumer choice by controlling supply (like oil) or distribution (like railroads) or infrastructure (like telephone wires); rather, consumers are self-selecting onto the Aggregator’s platform because it’s a better experience.

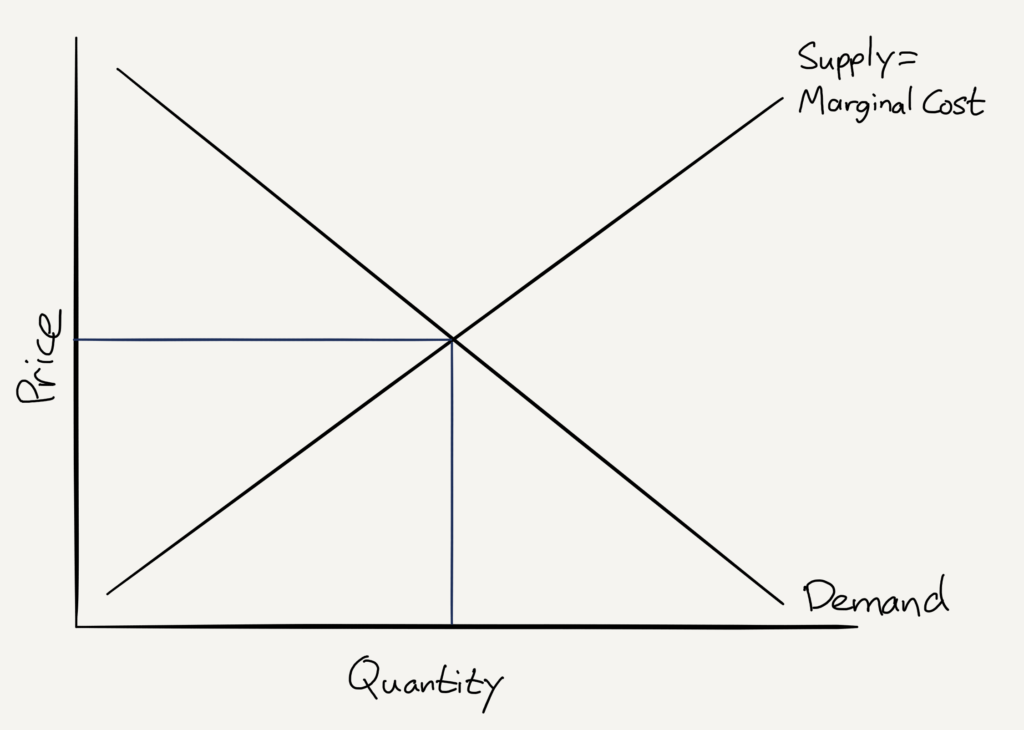

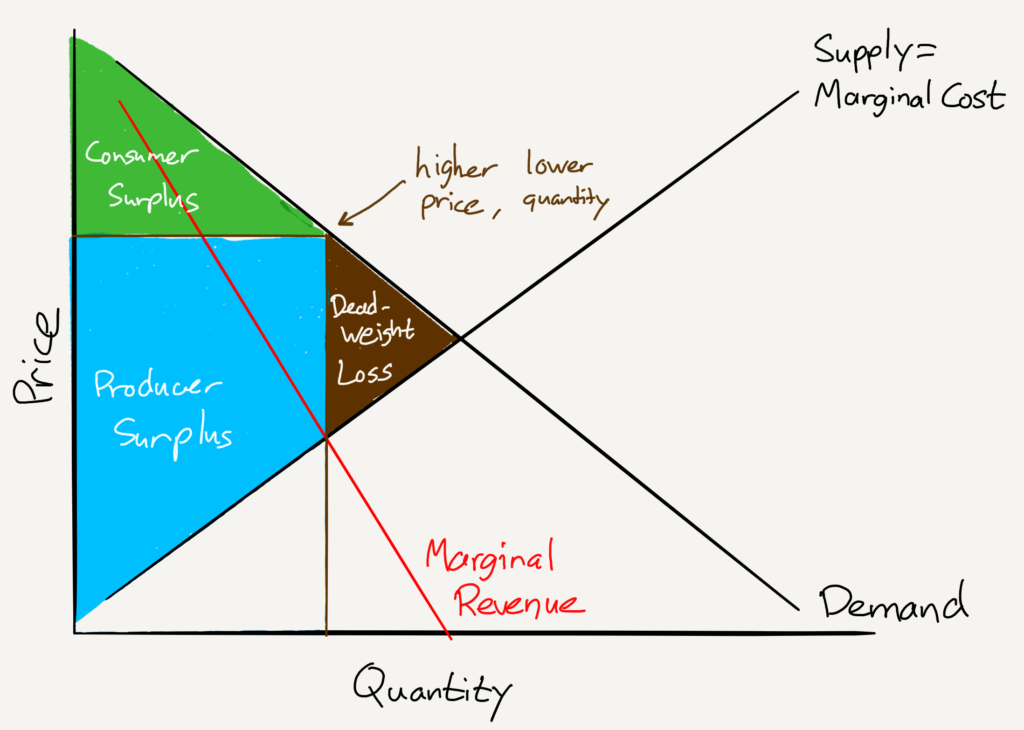

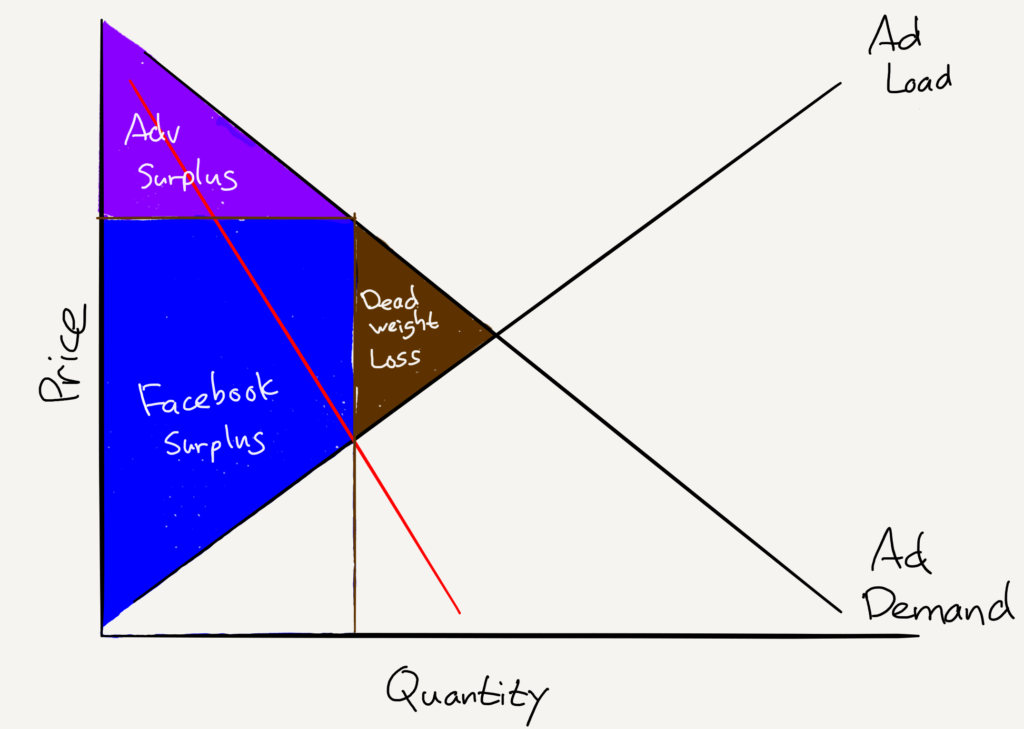

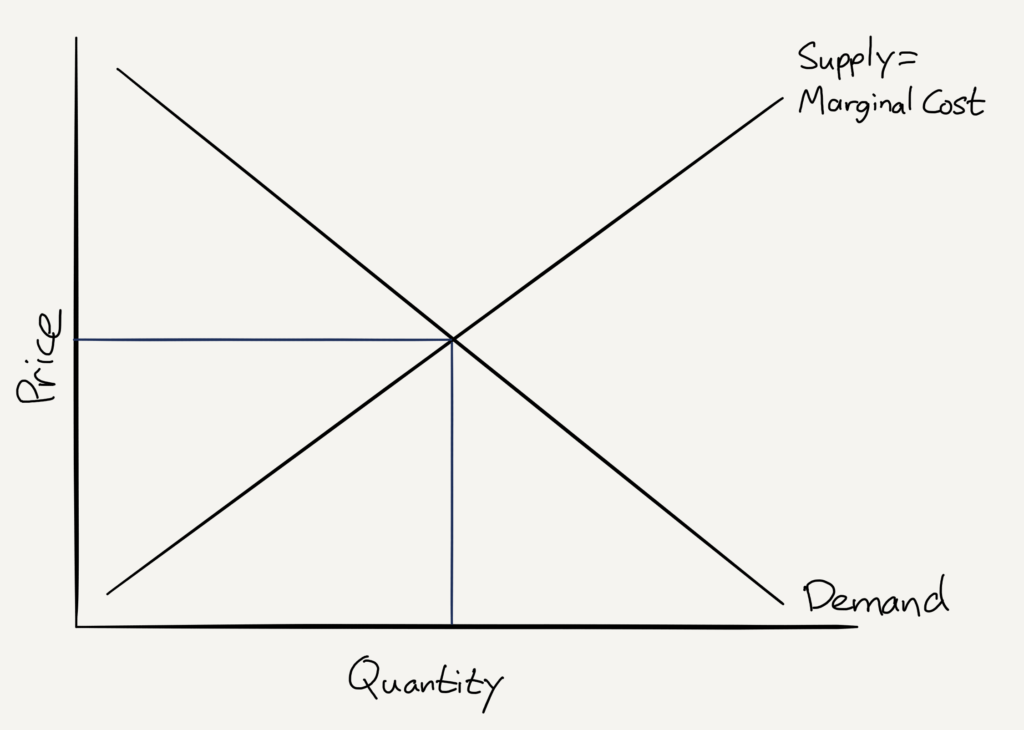

This self-selection, particularly onto a “free” platform, makes it very difficult to calculate what cost, if any, Facebook’s seeming monopoly exacts on society. Consider the Econ 101 explanation of why monopolies are problematic:

- In a perfectly competitive market the price of a good is set at the intersection of demand and supply, the latter being determined by the marginal cost of producing that good:1

-

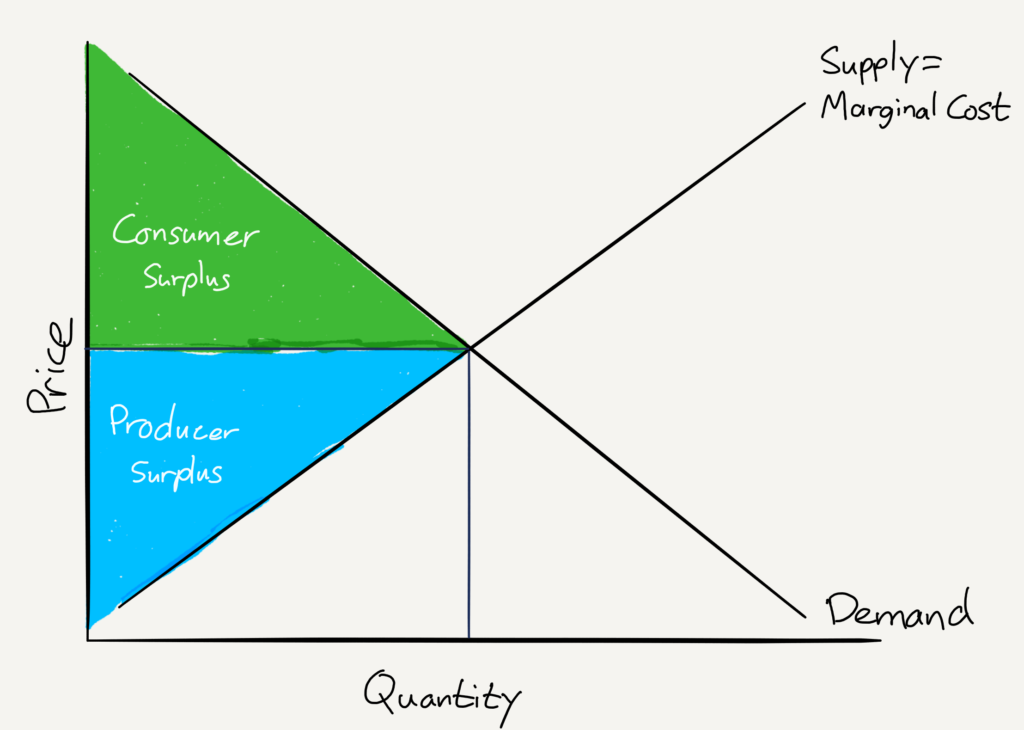

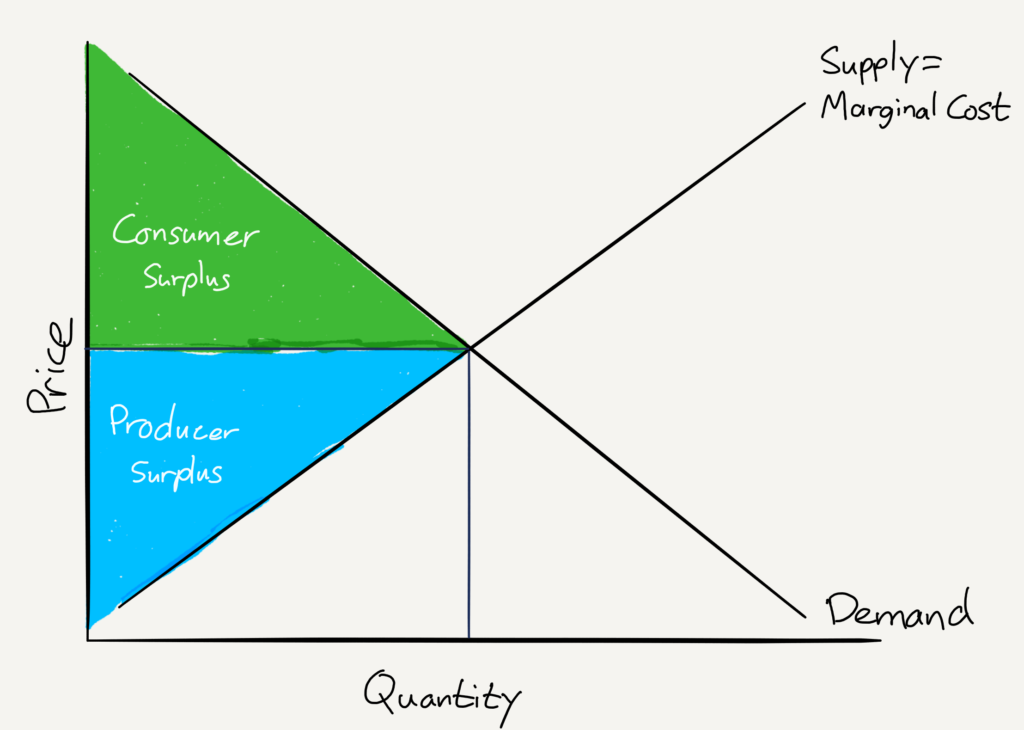

The “Consumer Surplus”, what consumers would have paid for a product minus what they actually paid, is the area that is under the demand curve but over the price point; the “Producer Surplus”, what producers sold a product for minus the marginal cost of producing that product, is the area above the marginal cost/supply curve and below the price point:

-

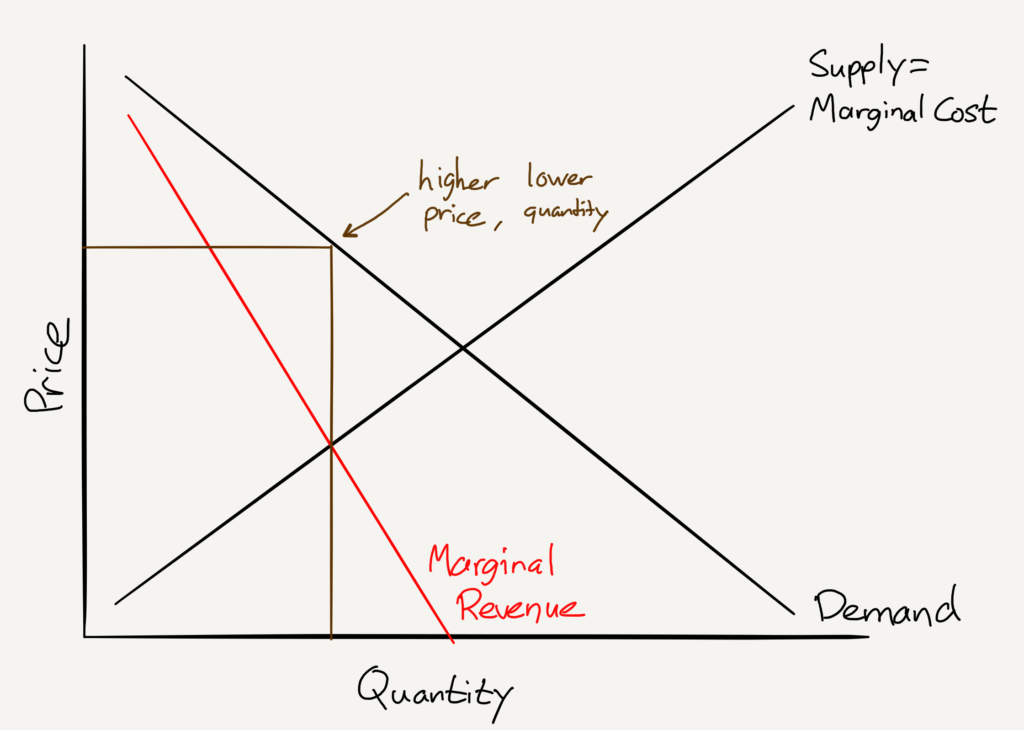

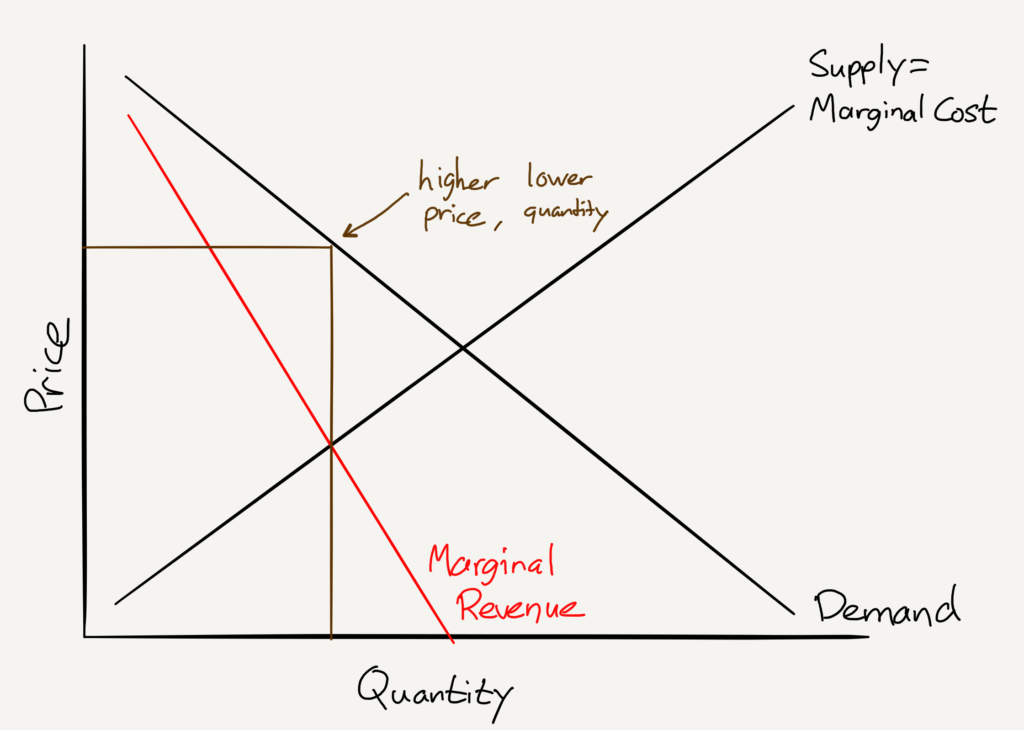

In a monopoly situation, there is no competition; therefore, the monopoly provider makes decisions based on profit maximization. That means instead of considering the demand curve, the monopoly provider considers the marginal revenue (price minus marginal cost) that is gained from selling additional items, and sets the price where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Crucially, though, the price is set according to the demand curve:

-

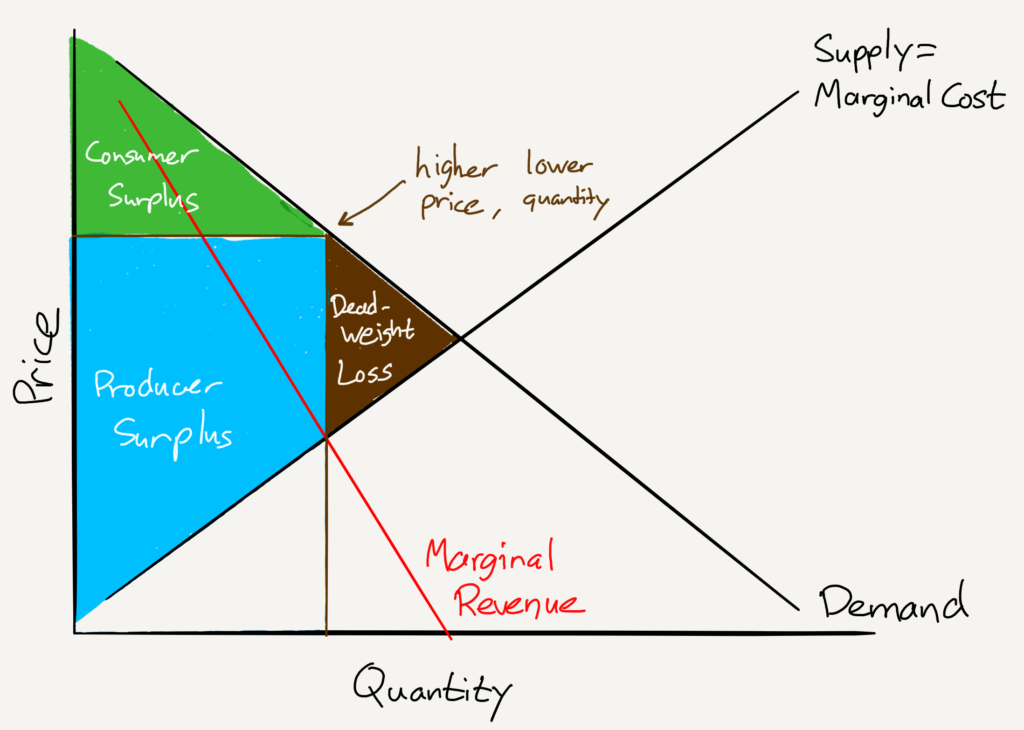

The result of monopoly pricing is that consumer surplus is reduced and producer surplus is increased; the reason we care as a society, though, is the part in brown: that is deadweight loss. Some amount of demand that would be served by a competitive market is being ignored, which means there is no surplus of any kind being generated:

The problem with using this sort of analysis for Facebook should be obvious: the marginal cost for Facebook of serving an additional customer is zero! That means the graph looks like this:

So sure, Facebook may have a monopoly in social networking, and while that may be a problem for Snap or any other would be networks, Facebook would surely argue that the lack of deadweight loss means that society as a whole shouldn’t be too bothered.

Facebook and Content Providers

The problem is that Facebook isn’t simply a social network: the service is a three-sided market — users, content providers, and advertisers — and while the basis of Facebook’s dominance is in the network effects that come from connecting all of those users, said dominance has seeped to those other sides.

Content providers are an obvious example: Facebook passed Google as the top traffic driver back in 2015, and as of last fall drove over 40% of traffic for the average news site, even after an algorithm change that reduced publisher reach.

So is that a monopoly when it comes to the content provider market? I would argue yes, thanks to the monopoly framework above.

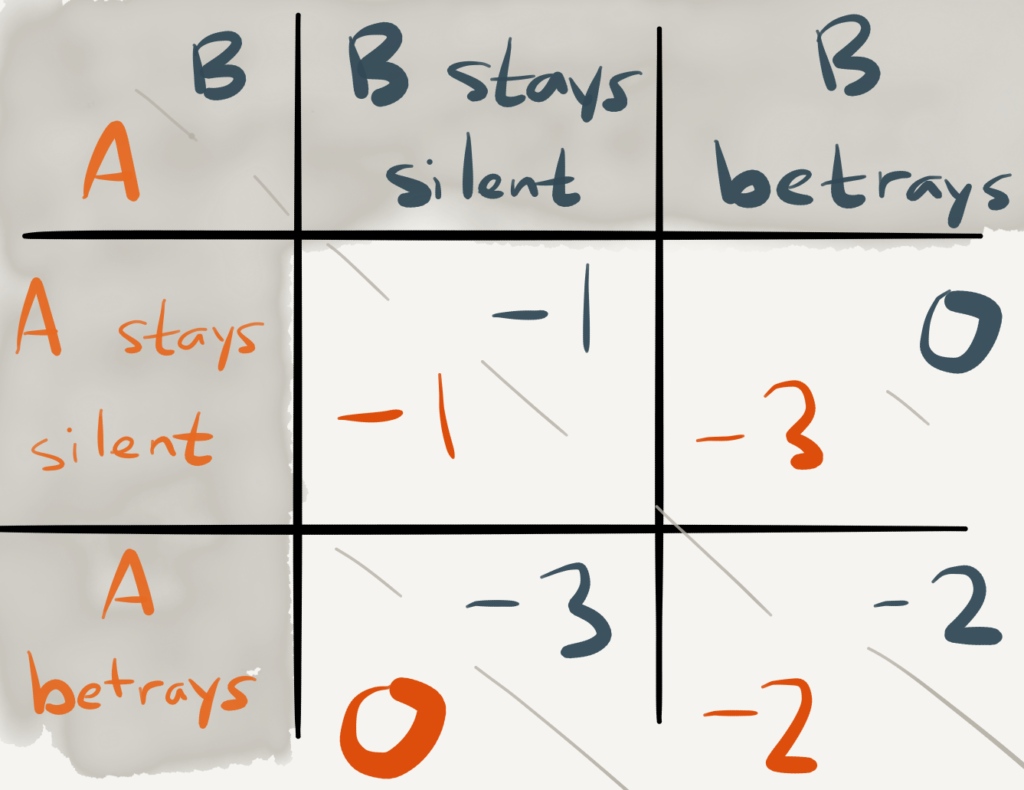

Note that once again we are in a situation where there is not a clear price: no content provider pays Facebook to post a link (although they can obviously make said link into an advertisement). However, Facebook does, at least indirectly, make money from that content: the more users find said content engaging, the more time they will spend on Facebook, which means the more ads they will see.

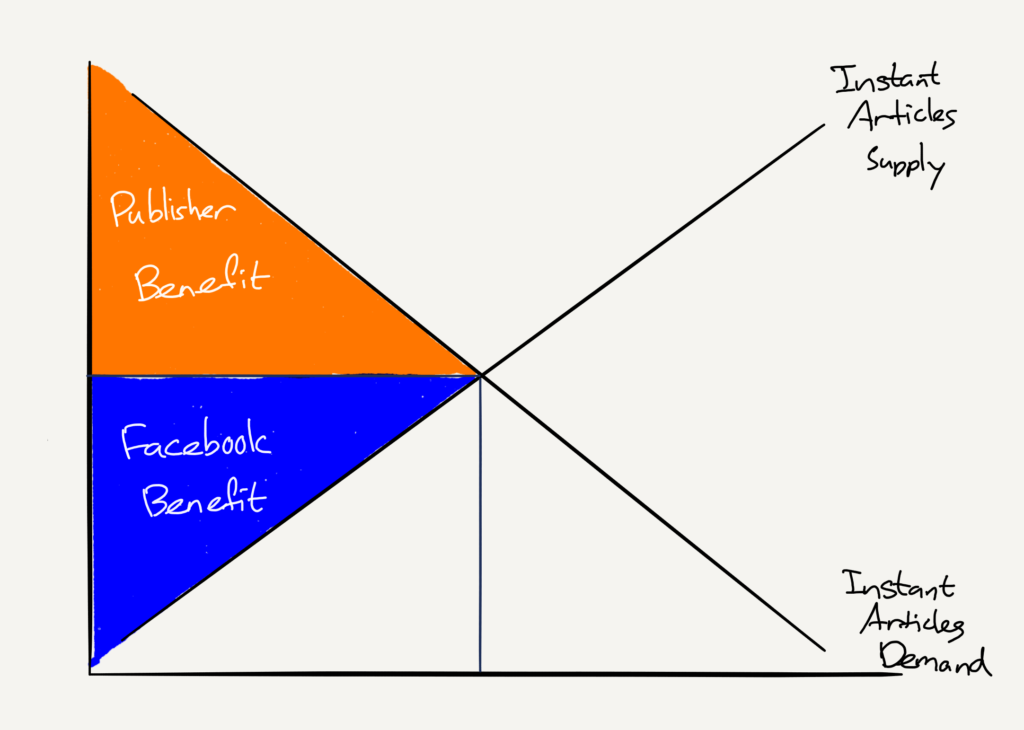

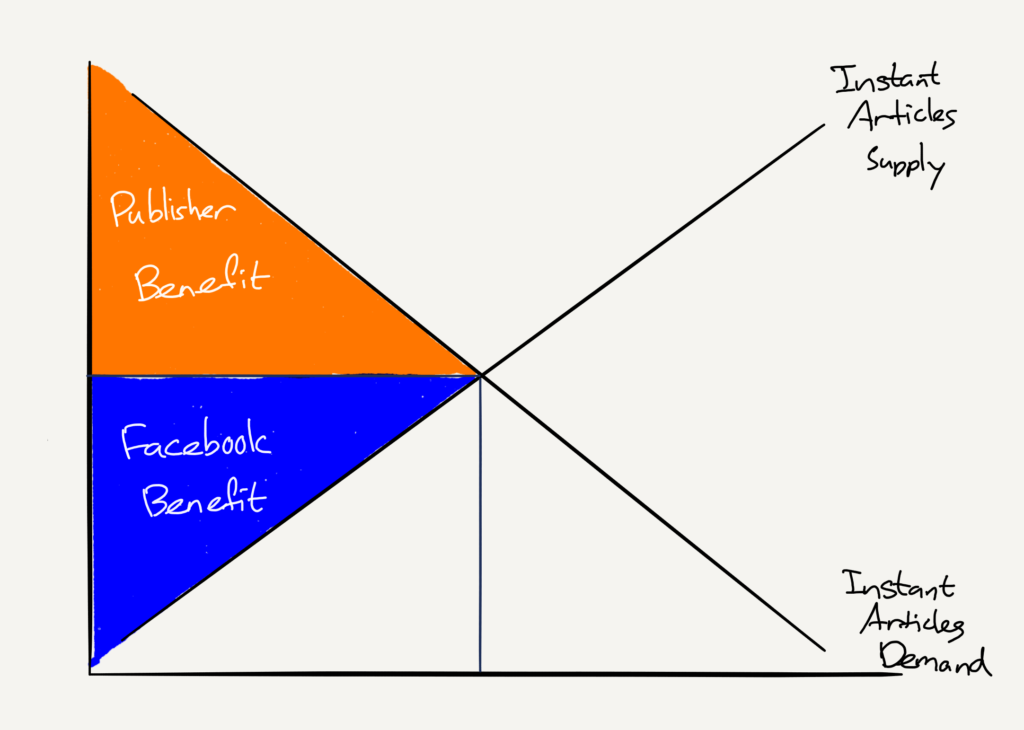

This is why Facebook Instant Articles seemed like such a brilliant idea: on the one side, readers would have a better experience reading content, which would keep them on Facebook longer. On the other side, Facebook’s proposal to help publishers monetize — publishers could sell their own ads or, enticingly, Facebook could sell them for a 30% commission — would not only support the content providers that are one side of Facebook’s three-sided market, but also lock them into Facebook with revenue they couldn’t get elsewhere. The market I envisioned would have looked something like this:

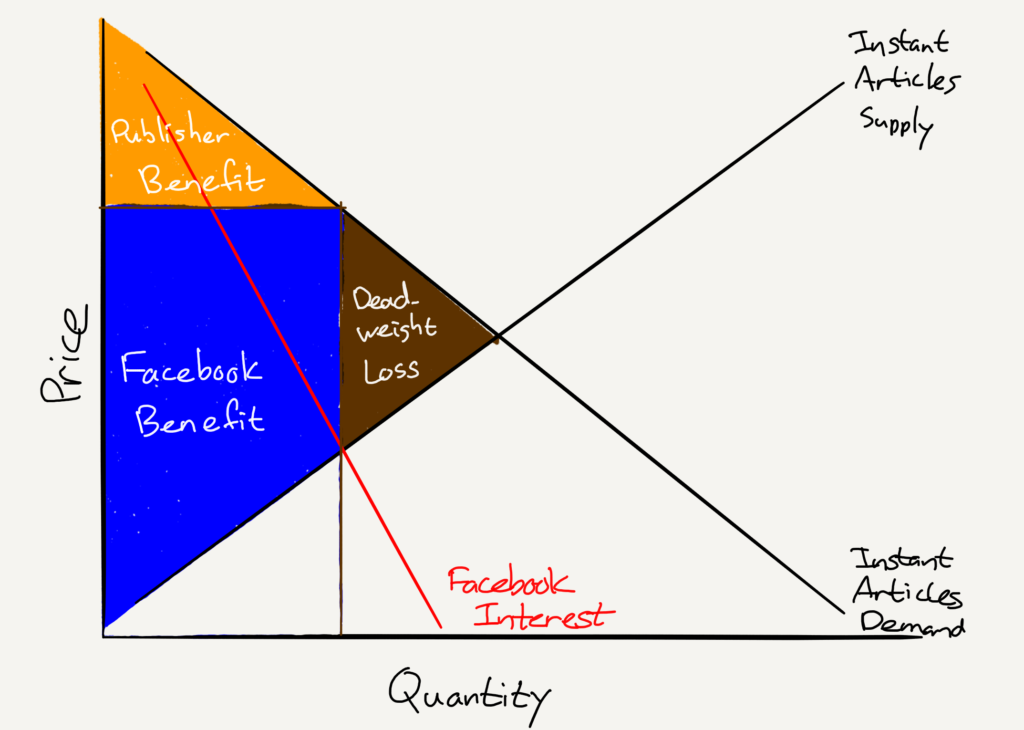

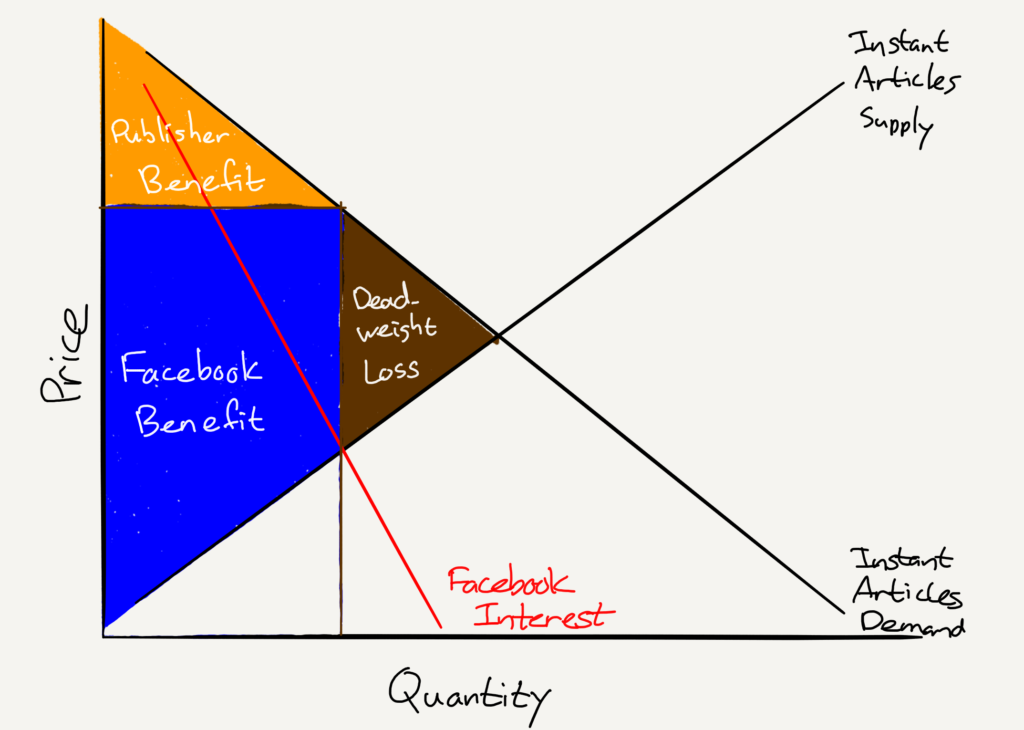

However, Instant Articles haven’t turned out the way I expected: the consumer benefits are there, but Facebook has completely dropped the ball when it comes to monetizing the publishers using them. That is not to say that Facebook isn’t monetizing as a whole, thanks in part to that content, but rather that the company wasn’t motivated to share. Or, to put it another way, Facebook kept most of the surplus for itself:

In this case, it’s not that Facebook is setting a higher price to maximize their profits; rather, they are sharing less of their revenue; the outcome, though, is the same — maximized profits. Keep in mind this approach isn’t possible in competitive markets: were there truly competitors for Facebook when it came to placing content, Facebook would have to share more revenue to ensure said content was on its platform. In truth, though, Facebook is so dominant when it comes to attention that it doesn’t have to do anything for publishers at all (and, if said publishers leave Instant Articles, well, they will still place links, and the users aren’t going anywhere regardless).

Facebook and Advertisers

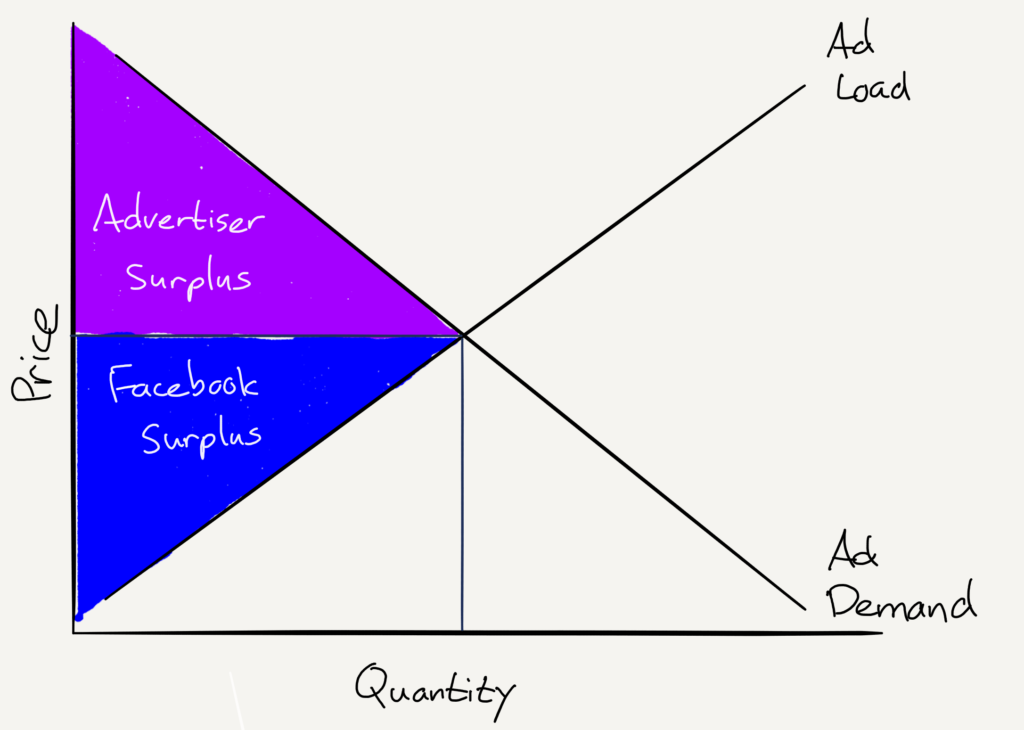

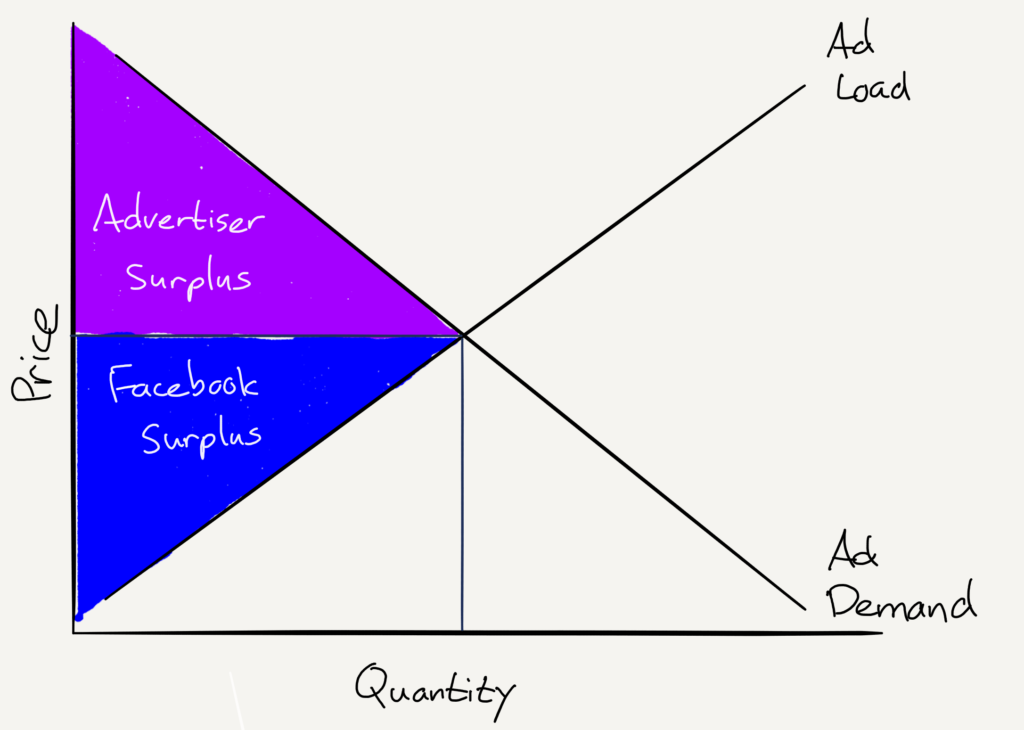

There may be similar evidence — that Facebook is able to reduce supply in a way that increases price and thus profits — emerging in advertising. In a perfectly competitive market the cost of advertising would look like this:

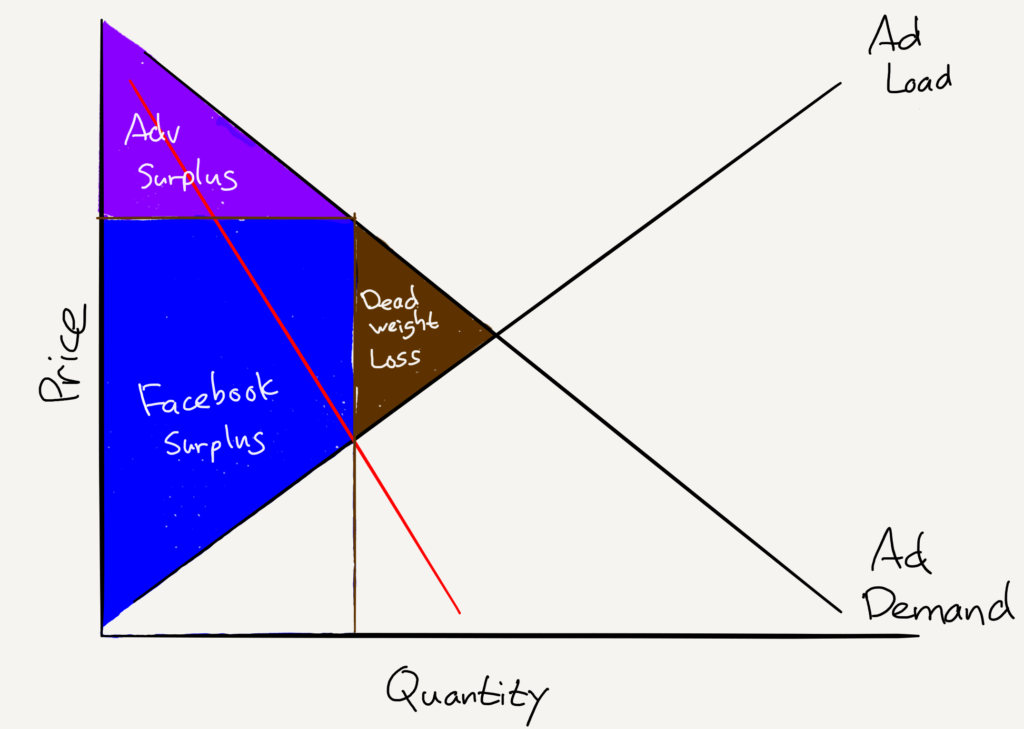

Facebook, though, will soon be limiting quantity, or at least limiting its growth. On last November’s earnings call CFO Dave Wehner said that Facebook would stop increasing ad load in the summer of 2017 (i.e. Facebook has been increasing the number of ads relative to content in the News Feed for a long time, but would stop doing so). What was unclear — and as I noted at the time, Wehner was quite evasive in answering this — was whether or not that would cause the price per ad to rise.

There are two possible reasons for Wehner to have been evasive:

- Prices will not rise, which would be a bad sign for Facebook: it would mean that despite all of Facebook’s data, their ads are not differentiated, and that money that would have been spent on Facebook will simply be spent elsewhere

- Prices will rise, which would mean that Facebook’s ads are differentiated such that Facebook can potentially increase profits by restricting supply

To put the second possibility in graph form:

Note that Facebook has already said that revenue growth will slow because of this change; that, though, is not inconsistent with having monopoly power. Monopolists seek to maximize profit, not revenue. Alternately, it could simply be that Facebook is worried about the user experience; it will be fascinating to see how the company’s bottom line shifts with these changes.

Monopolies and Innovation

Still, even if Facebook does have monopoly power when it comes to content discovery and distribution and in digital advertising, is that really a problem for users? Might it even be a good thing?

Facebook board member Peter Thiel certainly thinks so. In Zero to One Thiel not only makes the obvious point that businesses that are monopolies are ideal, but says that models like the ones I used above aren’t useful because they presume a static world.

In a static world, a monopolist is just a rent collector. If you corner the market for something, you can jack up the price; others will have no choice but to buy from you…But the world we live in is dynamic: it’s possible to invent new and better things. Creative monopolists give customers more choices by adding entirely new categories of abundance to the world. Creative monopolies aren’t just good for the rest of society; they’re powerful engines for making it better.

The dynamism of new monopolies itself explains why old monopolies don’t strangle innovation. With Apple’s iOS at the forefront, the rise of mobile computing has dramatically reduced Microsoft’s decades-long operating system dominance. Before that, IBM’s hardware monopoly of the ’60s and ’70s was overtaken by Microsoft’s software monopoly. AT&T had a monopoly on telephone service for most of the 20th century, but now anyone can get a cheap cell phone plan from any number of providers. If the tendency of monopoly businesses were to hold back progress, they would be dangerous and we’d be right to oppose them. But the history of progress is a history of better monopoly businesses replacing incumbents. Monopolies drive progress because the promise of years or even decades of monopoly profits provides a powerful incentive to innovate. Then monopolies can keep innovating because profits enable them to make the long-term plans and to finance the ambitious research projects that firms locked in competition can’t dream of.

The problem is that Thiel’s examples refute his own case: decades-long monopolies like those of AT&T, IBM, and Microsoft sure seem like a bad thing to me! Sure, they were eventually toppled, but not after extracting rents and, more distressingly, stifling innovation for years. Think about Microsoft: the company spent billions of dollars on R&D and gave endless demos of futuristic tech; the most successful product that actually shipped (Kinect) ended up harming the product it was supposed to help.2

Indeed, it’s hard to think of any examples where established monopolies produced technology that wouldn’t have been produced by the free market; Thiel wrongly conflates the drive of new companies to create new monopolies with the right of old monopolies to do as they please.

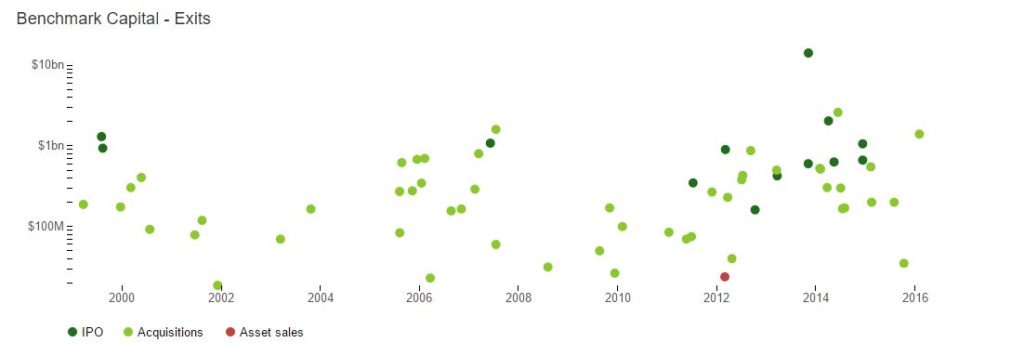

That is why Facebook’s theft of not just Snapchat features but its entire vision bums me out, even if it makes good business sense. I do think leveraging the company’s network monopoly in this way hurts innovation, and the same monopoly graphs explain why. In a competitive market the return from innovation meets the demand for customers to determine how much innovation happens — and who reaps its benefits:

A monopoly, though, doesn’t need that drive to innovate — or, more accurately, doesn’t need to derive a profit from innovation, which leads to lazy spending and prioritizing tech demos over shipping products. After all, the monopoly can simply take others’ innovation and earn even more profit than they would otherwise:

This, ultimately, is why yesterday’s keynote was so disappointing. Last year, before Facebook realized it could just leverage its network to squash Snap, Mark Zuckerberg spent most of his presentation laying out a long-term vision for all the areas in which Facebook wanted to innovate. This year couldn’t have been more different: there was no vision, just the wholesale adoption of Snap’s, plus a whole bunch of tech demos that never bothered to tell a story of why they actually mattered for Facebook’s users. It will work, at least for a while, but make no mistake, Facebook is the only winner.

- If any individual firm’s marginal costs are higher, they will go out of business; if they are lower they will temporarily dominate the market until new competitors enter. Yes, this is all theoretical!

- I’m referring to the fact the Xbox One had a higher price and lower specs than the PS4, thanks in large part to the bundled Kinect

![Our Warming World: The Future of Climate Change [INFOGRAPHIC]](https://futurism.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/climate-change-timeline_home_v1-900x600.jpg)

At GDC 2017, Epic Games' Ben Lewis-Evans dispels the "neuromyths" around dopamine and offers devs a deep dive into the psychology behind reward systems in game design. ...

At GDC 2017, Epic Games' Ben Lewis-Evans dispels the "neuromyths" around dopamine and offers devs a deep dive into the psychology behind reward systems in game design. ... More than a year after its public debut, Sony's mobile game division is releasing its first game in Japan: a free-to-play spin on Everybody's Golf (or as its known in the West, Hot Shots Golf.) ...

More than a year after its public debut, Sony's mobile game division is releasing its first game in Japan: a free-to-play spin on Everybody's Golf (or as its known in the West, Hot Shots Golf.) ...

In a blast from the past, Nintendo has announced plans to bring back the NES in bite-sized form this November ...

In a blast from the past, Nintendo has announced plans to bring back the NES in bite-sized form this November ...