Some of my friends have depression and have asked me for some suggestions.

These will be inferior to reading official suggestions, but you will probably not read official suggestions, and you may read this. Just so we’re clear, all opinions here are my own, they are not endorsed by the hospital I work at, they do not constitute medical advice, I have a known habit of being too intrigued by extremely weird experimental ideas for my own good, and you read this at your own risk. I am still an intern (a very new doctor) and my knowledge is still very slim compared to more experienced professionals.

Overall I think this is more of a starting point for your own research rather than something I would expect people to have good results following exactly as written.

And one more apology: originally I tried to include links to appropriate studies with each intervention, but there are so many different studies, and it’s so easy to pick apart each, and so much of the research is based on a gestalt impression after having read three dozen studies rather than on any individual one – that I decided that listing the evidence fairly would require this to be ten times as long and much more academic. I’m doing that thing where “perfect is the enemy of good enough” and trying to actually get this up online. I’m happy to discuss evidence or lack thereof for any particular therapy in the comments.

Now that that’s over: first I’m going to talk about figuring out if you need help. Then I’m going to recommend you see a psychiatrist. Then I’m going to accept that in reality a lot of people for whatever reason can’t or won’t see a psychiatrist, and grudgingly recommend some lifestyle interventions you can make. Then I’m going to accept that in reality a lot of people for whatever reason can’t or won’t make lifestyle interventions, and grudgingly recommend some over-the-counter medications and supplements that might be helpful.

I. Do You Have Depression?

Major depressive disorder is the clinical condition that best corresponds to what people usually mean when they say “depression”. Only a licensed professional can officially determine whether or not you have major depressive disorder. But if you feel miserable all the time, you might be able to make one heck of a good guess.

The PHQ-9 is a well-known and validated screening tool for depression; you can take it at the linked site. It cannot diagnose you officially, but once again, it can help you make one heck of a good guess, and if you get a high score it might inspire you to get to a doctor’s office.

Overall there’s not exactly an epidemic of perfectly healthy people misdiagnosing themselves as depressed, but there are a couple of things worth keeping in mind:

- You can have depression even if there is a good reason for you to be depressed – for example, if you’re depressed because you lost your job. If you have the symptoms, and it’s been going on more than two weeks, it counts. These kinds of depression seem to respond to treatment about the same as kinds that come on for no reason at all.

- Depression usually lasts a long time. Depressive episodes usually last weeks to months. Someone who is depressed for a day or two after something happens probably does not have depression. Even if they are unreasonably depressed for a day or two after something happens, so much so that they seem to have a mental disorder, it may be a different mental disorder.

- People with bipolar disorder (“manic-depressive disorder”) are often depressed some of the time. These depressive episodes can last a long time, just like the ones in traditional depression. However, bipolar disorder is a completely different disease and needs completely different treatment. If you sometimes have “manic” or “hypomanic” episodes – several days to weeks of having abnormally high energy, abnormally low sleep, abnormally high self-esteem, abnormally short temper, and poor impulse control – then you probably have bipolar disorder instead of depression. If your doctor or psychiatrist has diagnosed you with depression and started treating you with antidepressants and you don’t seem to be getting better, then you have found your problem. Politely bring up your history of manic or hypomanic episodes and ask whether she wouldn’t prefer to diagnose you with bipolar disorder instead.

II. Please Go To A Doctor

If you have depression, your best bet is to go to a doctor. A doctor can diagnose you and connect you with useful prescription-only medications like antidepressants. You do not need to go to a psychiatrist to get antidepressants. Your family doctor will be able to prescribe them. You will only need to go to a psychiatrist if your depression fails treatment with normal medications and someone needs to figure out a more complicated plan.

The failure mode of medical professionals I see most often seems to be something like this:

Patient: I’m depressed.

Doctor: Here, have an SSRI

Patient: (three months later) I’m still depressed.

Doctor: Well, keep taking that SSRI I gave you, I’m sure you’ll get better eventually.

Patient: (six months later) I’m still depressed.

Doctor: Sheesh! I already gave you an SSRI, what else do you want from me?

There are dozens of different depression medications. If one doesn’t work, very commonly another one will. Depression treatment is difficult, because there’s no way of knowing beforehand what medications will or won’t work for any individual person. The correct solution is to start with the safest medications, see if they work or not, and gradually move up to stronger medications with more side effects. But this doesn’t work if your doctor just tells you to keep taking whatever you’re taking forever whether or not it’s doing anything.

A lot of people are reluctant to second-guess their doctor on this sort of thing. So let me provide you with a loose approximate algorithm that you can follow when going to a doctor or psychiatrist about depression. Many doctors have very good reasons for deviating from this algorithm, but if they are nice people they should be willing to explain what their reasons are to your satisfaction.

1. Rule out organic causes

When your doctor diagnoses you with depression, they may perform several blood tests. The most important ones are a thyroid test for hypothyroidism, and a blood count for anaemia. Hypothyroidism and anaemia are medical illnesses that can cause depression. If you have them, then psychiatric treatment for depression won’t help and won’t treat the underlying potentially dangerous condition.

Symptoms of hypothyroidism besides depression include feeling unusually cold, gaining weight despite good diet, constipation, pale dry skin, weakness, and disturbed menstrual periods if female. It is easily detectable with blood tests and easily treatable with thyroid hormone, but someone’s got to look for it.

Symptoms of anaemia besides depression include looking very pale, feeling weak and tired, and occasionally pica, the compulsion to eat non-food items like ice or dirt. It is very common in women with heavy periods. It is easily detectable with blood tests and usually easily treatable with iron supplements.

If you’re being treated for depression with psychiatric medication, and it’s not helping, and you have some of those symptoms, and nobody ever did blood tests on you, politely ask your doctor if you’ve been tested for hypothyroidism and anaemia (people get lots of blood draws all the time and lots of the time they’ve just forgotten). If you haven’t been, politely ask why not. If your doctor doesn’t have a good reason, and your depression isn’t getting better, politely ask if they think it would be a good idea to check for at least those two conditions and maybe some vitamin deficiencies.

2. Choose between pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or both

Many to most doctors and psychiatrists will assume that you want medication. This is a pretty good assumption most of the time. Medications and psychotherapy are about equally effective in treating depression, but psychotherapy costs a lot more, takes more time, and is harder to get your insurance to cover.

Still, a lot of people who would have preferred psychotherapy never get the option. And if you’ve tried lots of medications that haven’t worked, maybe you’ll luck out with psychotherapy. You can either get your doctor to recommend someone or find someone yourself.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is a nice neutral therapy for depression with as high a success rate as any other. It usually consists of a couple of sessions in which somebody talks to you about the way you deal with and think about problems and maybe assigns you some homework. There’s no talking about your mother or about your sexual fetishes. 6 to 12 one hour sessions would be a pretty standard starter course.

Having both psychotherapy and medication has been associated with a better treatment rate than either one alone.

3. Start with an SSRI

SSRIs are the most commonly used antidepressant medication. They are no stronger or weaker than other antidepressants, but they do have fewer side effects, which makes them first-line.

There is a lot of worry that SSRIs are not much better than a placebo for people with mild to moderate depression (almost everyone agrees they are effective for severe depression). Some studies have seemed to confirm these fears, others have seemed to refute them. I am leaning towards “marginally better than placebo”. However, this is a completely academic debate for you, because you are not going to get placebo. Your choice is between SSRIs or nothing. Everyone everywhere agrees SSRIs are much better than nothing.

All SSRIs are approximately equally effective. Your doctor or psychiatrist’s choice of SSRI comes down to which side effects you are most willing to tolerate, the exact shape of your depressive symptoms, and which drug company gives out the most pens and coffee mugs with the name of their medication on them. Celexa or Lexapro (citalopram or escitalopram) are good first choices for most people, but it is hard to go disastrously wrong here.

Bupropion is not an SSRI, but is also an appropriate first choice. SNRIs like Effexor (venlafaxine), as well as mirtazapine which is sort of in a weird little class of its own, are also okay for certain people. If your depression is very severe, your doctor might skip this step and go further down in the algorithm, which is also okay. Some psychiatrists also may have their own idiosyncratic preferences which are probably okay as well if they can explain their reasoning to you.

Many people worry about the side effects of SSRIs. In my opinion many of these worries are exaggerated. The most common side effect is decreased sexual drive and performance, which can occur in more than half of users. Other side effects include nausea, diarrhea, insomnia, and weight gain, which occur less frequently. These side effects are usually temporary and go away when you stop using the drug. If you’re worried about sexual side effects, bupropion is much less likely to have these, with the tradeoff being a few other effects like more insomnia.

Some antidepressants have discontinuation syndromes, which mean you feel sick when you’re withdrawing from them. Effexor (venlafaxine) and Paxil (paroxetine) are particularly bad. A competent doctor or psychiatrist will take you off these slowly so that you avoid any bad effects.

4. Give it a little while to work

Antidepressants take some time to start working.

This is less true now than it was a while ago – it used to be believed they almost never worked until a few weeks had gone by, whereas now we know that there can sometimes be some improvement pretty quickly. But other times there isn’t. Although you can hope for improvement within a week or two, give an antidepressant at least four weeks, just to be sure you’re not selling it short.

If you can’t wait four weeks, you may want to consider mirtazapine, which works a little more quickly. But you’re still not going to pop a single pill and start feeling much better.

5. Fiddle around

If a drug seems to work a little bit in the first month or two, it might be worth raising the dose.

If it doesn’t work at all within the first month or two, you could still try raising the dose, but you might also want to try switching to a different drug. For example, if one SSRI doesn’t work, you could try switching to a different SSRI.

If SSRIs don’t work, this might be a good time to try antidepressants from other newer classes. Effexor (venlafaxine), mirtazapine, and bupropion would be three very good choices here. All three are pretty safe and very commonly used. You could also move to a tricyclic antidepressant, which have just a little bit more side effects than some of the newer classes that have replaced them by which can sometimes be very successful in certain patients when SSRIs have failed.

If nothing works alone, your doctor will probably try combining a couple of these drugs and seeing if that helps.

6. Get serious

Once treatment with SSRIs and the usual SSRI replacements has failed, you get to start trying more serious stuff. Usually the drugs here either have worse side effects or are still a little bit experimental. These will probably be prescribed by a psychiatrist and not your regular family doctor.

Atypical antipsychotics have been found to be quite effective in depression. Unfortunately, many have side effects, including weight gain and increased risk of diabetes. Abilify has fewer of these, which makes it a very popular choice. Seroquel has a few more, but it also relieves anxiety and helps sleep, which makes it very popular as well. Olanzapine has a lot of good evidence behind its antidepressant properties, but its side effects can be very severe, so I would be more reluctant to prescribe it than either of the other two.

MAOIs are an old antidepressant medication that went out of fashion when SSRIs came around. A lot of patients remember them very fondly; according to anecdote they are very powerful and can give people a very good mood. However, they have a bad habit of causing life-threatening hypertensive crises at inconvenient times if you eat the wrong thing, where “the wrong thing” includes everything on a long list of foods your doctor has to give you and lecture you about before they can be prescribed. And just to warn you, cheese, beer, and chocolate are definitely included. The Europeans seem to have a less dangerous MAOI called mobeclomide which hasn’t been approved in the US yet, but I don’t know anything about it.

Thyroid hormone is very rarely used as an antidepressant augmentation, but there is some preliminary evidence that it is as effective as lithium with fewer side effects, even for people without obvious underlying thyroid problems.

Lithium is a mood stabilizer more commonly used in bipolar disorder, but which has some indication for depression as well. Usually it is taken along with another antidepressant as “augmentation”. It works pretty well, and is especially good at decreasing suicidality, impulsivity, and aggression. Unfortunately it’s not the safest medication in the world and usually requires some annoying blood tests to make sure you keep getting the right amount of it.

Modafinil shows some promise as an antidepressant supplementation strategy and is discussed in more detail in section IV below.

This might also be a good time to double-check that you were definitely tested for underlying medical conditions like hypothyroidism and anaemia, and that you definitely don’t have bipolar disorder or some other condition mimicking depression. Or you might want to look down and try some of the lifestyle interventions and supplements later in this list.

7. Get very, very serious

Electroconvulsive therapy gets a bad rap from old movies where we see people who “misbehave” in the mental institution getting what look like very painful electric shocks.

Modern electroconvulsive therapy is done with the patient sedated. You are pleasantly asleep, your limbs aren’t flailing about or anything, and it can be done on an outpatient basis with you going home as soon as you’re done.

There are a lot of worries about side effects. Some people experience some memory loss, especially of the couple of weeks before the treatment. Most of the time these memories come back. Sometimes they don’t. But how much do you want to remember the week when you were so depressed you needed ECT, anyway? Longer-term side effects are less well-known. Some people think a lot of ECT isn’t good for your brain, but if the effect exists it’s small enough that people are still debating whether or not they’ve really picked it up.

But the thing is, ECT really, really works. People get to the point where everything else has failed, and they’ve been on seven hundred different medications without feeling any better, and they’re ready to give up, and then they get ECT and start whistling happy songs and dancing the polka. I won’t say it works 100% of the time, because no medical treatment works 100% of the time. But in psychiatry, where expectations are always low, it’s the closest thing we’ve got to a miracle cure.

Speaking of miracle cures, a couple of people have asked me about ketamine. Ketamine does show unusually rapid and effective action in treating depression. However, it is currently still very experimental and your doctor or psychiatrist will not be able to give it to you unless by a strange coincidence they are one of the few researchers working with this drug. Further, there are still a lot of problems with ketamine therapy for depression. First, the drug is highly hallucinogenic, sometimes in very scary ways; in experiments subjects are put under anaesthetic first so they don’t have to consciously experience the hallucinations. Second, it’s not yet clear how long-acting it is; anything that required long-term ketamine therapy (say, a ketamine dose a week) would be impractical both because of the hallucinations and because the drug has serious side effects and is addictive. Although it is very exciting to researchers, it is probably not very useful to you.

Anyway, that’s the algorithm – which I lifted from a couple of treatment guidelines – that I would recommend people watch to see if their doctor follows. Because I feel like – if someone is really really depressed, to the point where it’s ruining their lives, and they are begging for help, and their psychiatrist tries all of steps one to seven, and even the ECT doesn’t help them, then they can consider saying “Well, I’ve done everything I can”, giving up, and lowering their expectations. Any doctor who gives up before they’ve reached that point has no excuse.

How do you find a good psychiatrist?

I have no great advice here, except that if you think your psychiatrist is terrible, you are probably right. Even if you are not right, your psychiatrist is apparently terrible for you. See if your insurance allows you to switch psychiatrists. If they do, try it and see if the next one is any better.

If a psychiatrist is doing something completely unlike the treatment algorithm in Part A, ask them to explain why. Be willing to accept any explanation, because treating depression is hard and there are a lot of different valid approaches. But if they refuse to explain and tell you that you’re a bad person for asking, you miiiiiiight want to see if you have other options.

There are a lot of doctor rating sites. Ratemds.com or healthgrades.com are among the bigger ones. These sites are not very valuable on the margin; you do sometimes get one guy who had to sit in the waiting room a little too long going on a personal campaign to destroy someone’s reputation. But on the tails, if there’s a doctor who is universally hated by every single one of her patients, this can be a strong warning sign.

People in mental health support groups are absurdly willing to share their opinions of various psychiatrists. Just don’t be surprised if you can’t get them to shut up once you’ve gotten your information.

Kate Donovan has a good guide to finding a psychotherapist, with partial crossover to the skill of finding a psychiatrist.

How do you see a psychiatrist without worrying you will be committed to an institution?

This is something I see a lot of people worry about, and something that prevents a lot of people from seeing a doctor or especially a psychiatrist. I think it happens less in reality than it does in people’s fears, but it does sometimes happen in reality, and enough people avoid getting help for this reason that it’s worth discussing briefly, at the possible risk of giving more airtime to something most people should not be worrying about.

The first and most important point is that very very few psychiatrists, whether good or bad, will commit people to a mental institution unless they are very sick. Even if you are very sick, there is only a small chance of a psychiatrist committing you against your will unless you say exactly the wrong thing.

Doctors and psychiatrists are legally required to commit patients to mental institutions if those patients are “a threat to themselves or others”. Usually this means a patient has said they want to commit suicide and they are probably really going to go through with it soon, or a patient has said they’re going to hurt someone else (or implied it: “He’s gonna get what’s coming to him”) and it wasn’t clearly meant metaphorically. They may also commit you if you are very paranoid on the grounds that paranoid people may try to pre-emptively attack those they believe are plotting against them – or if you are refusing to eat, on the grounds that if you don’t eat you die.

A good psychiatrist will differentiate between vague suicidal ideation (“Sometimes I feel like life isn’t even worth living, do you know what I mean?”) and specific suicidal ideation (“I will kill myself tomorrow using the gun hidden in the back of my pantry”), will explore the first type with an aim toward helping you, and will only involuntarily commit for the second type. I do not guarantee you will have a good psychiatrist.

Until you are sure your psychiatrist is trustworthy, you may want to steer clear of statements that sound suicidal, homicidal, or paranoid. Even in jest. Especially in jest. Until you have established absolute trust, please treat joking about suicide or homicide around your psychiatrist the same way you would treat joking about terrorism around airport security agents. I cannot overemphasize how important this is. If you won’t do it for yourself, do it for the sake of your poor overworked local inpatient psychiatrist, who is sick of hearing all his new patients say “I shouldn’t be here, I promise I was only joking!”

If you are genuinely suicidal, homicidal, or paranoid, but you are absolutely sure you are not an acute danger to anybody, and you trust your psychiatrist enough to tell him or her about these things – then make sure you phrase it in a way that specifies you are not an acute danger to anybody. For example “Sometimes I feel like I would be better off dead…BUT I AM DEFINITELY NOT GOING TO COMMIT SUICIDE BECAUSE THAT IS MORALLY WRONG AND I CARE A LOT ABOUT MY FAMILY AND I WANT TO LIVE!!!”. Or “Sometimes I feel like people are plotting against me…BUT NOT ANYBODY SPECIFIC AND I KNOW THAT’S NOT ACTUALLY TRUE!!!”

This should keep you relatively safe from involuntary committment unless your psychiatrist is truly awful.

III. Lifestyle Interventions

Not everyone can or will go to a doctor, and even those who do go to a doctor might want to try something more proactive on the side, so in this section I’m going to list some lifestyle interventions you can make.

1. Do therapy on yourself

If you can’t or won’t go to a therapist, a therapy workbook is a practical alternative. Cognitive Behavioral Workbook For Depression is rated 4.3/5 stars on Amazon, which I guess is sort of like being evidence-based. Many very smart people find these sorts of therapy workbooks to be a little condescending (“Really? I need to stop catastrophizing all the time? I never would have thought of that on my own!”) but other equally smart people find them useful, whether because they have new insights or because they repackage, remind, and rehearse what they already know. For 3$ for a used copy, that’s about 1% of the cost of most of the other interventions you could try.

2. SLEEP!

Put in all capitals with an exclamation point at the end of it to show how important I think it is.

Depression is weirdly linked to circadian rhythm and sleep. Poor sleep habits probably help cause and exacerbate depression. Unfortunately, depression also causes and helps exacerbate poor sleep habits, so it’s a kind of vicious cycle.

In a recent study, people who received cognitive behavioral therapy for sleep disturbances had double the recovery rate from depression of people who didn’t, suggesting that attacking insomnia is pretty much just as effective as the strongest drugs known. This avenue is severely underexplored and very promising.

The cognitive behavioral therapy for sleep disturbance is about one part basic CBT techniques of challenging your perceptions and beliefs, and one part the things your mother told you about sleeping in a dark room and not watching exciting TV shows right before bedtime. This therapy also has a cheap workbook with a 4.6 star Amazon rating. You can add whatever other high-tech exciting sleep cycle correctives you know – melatonin, magnesium, whatever – to what it tells you.

3. Exercise

I work in a psychiatric hospital. Once a week or so a social worker leads an exercise group there, and it is amazing how much better everyone does that day compared to the days before and after. Exercise seems to increase release of BDNF, an important brain chemical that depressed people don’t have enough of, and there have been several studies showing good effect.

Fast walking for a half hour five days a week seems to be enough to help. More exercise might help more. And exercising outside will get you more sunlight and vitamin D, whose relationship to depression remains controversial but which certainly can’t hurt.

4. Light therapy

Light therapy is hanging out around really bright lights for a while and hoping they cheer you up. The Cochrane Collaboration and a meta-analysis in a major psychiatric journal agree that they do, quite robustly (although there is still uncertainty about whether they add extra treatment to somebody already being treated with antidepressants).

Experts recommend a light therapy box emit 10,000 lux (a unit of light). Here’s a very official looking one that costs $200 and a somewhat less expensive one at $70.

Best practice is to keep it above your line of vision so your brain feels like it’s the sun, and sit near it for at least a half hour in the morning. Mayo Clinic tells you a little more about how to do it here.

5. Drugs are bad for you, mmkay?

The Simpsons described alcohol’s role in treatment far better than I can: “There’s nothing like a depressant to cure depression.” Except I think they were being sarcastic, and a lot of patients are serious.

Alcohol probably works in helping you forget about depression for a little while, but over the long term it makes you much more depressed. If you abuse alcohol, stop doing that.

Benzodiazepines (Xanax, Ativan, Klonopin) are, once again, good short-term solutions to anxiety. If you abuse them, they will probably contribute to your depression.

Smokers have more than twice the rate of depression than nonsmokers. There’s a lot of debate about whether it’s causal or noncausal, but some sophisticated statistical modeling seems to suggest there is indeed a real link. Also, getting lung cancer is depressing as heck.

I don’t know any studies linking heroin or cocaine to depression directly, but they probably take your life in a pretty depressing direction.

Obviously all of these drugs are hard to quit, and you might need the help of a medical practitioner.

6. Other things that make you happy

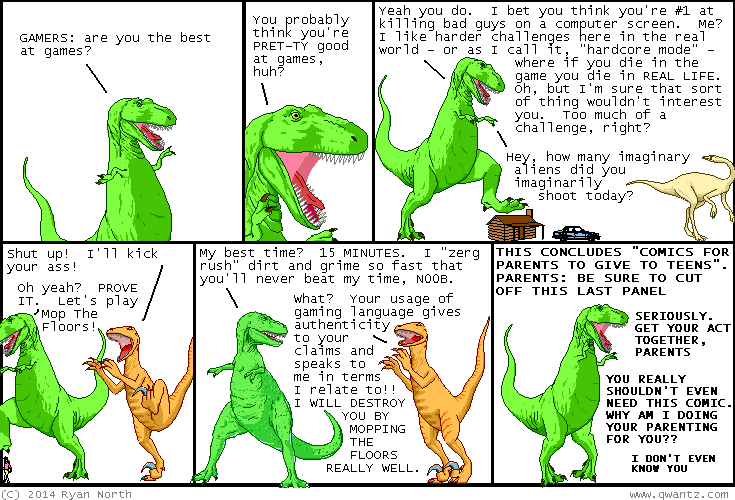

Cure Together is a really neat website where people with illnesses record all the things – medical and nonmedical – they tried and how well it worked for them. It obviously trades off the well-controlled conditions of an experiment in exchange for sheer amount of data, but it’s a useful adjunct to other ways of getting information. You can find their chart for depression here.

Just from looking at it, exercise and SLEEP! are right up at the top, but people also mention things that more scientifically-inclined people would probably never think of, like spending time with a pet, listening to music, and watching funny TV shows.

IV. Supplements

Despite the best of intentions, I think a lot of people are going to skip parts II and III and start down here. I think that would be a mistake, but I understand depressed people don’t always have the energy for big lifestyle changes or the willpower to take the anxiety-provoking step of seeing a psychiatrist. So sure. Let’s try supplements.

A reminder – supplements are chemically active compounds. They can have side effects. You should look up what they are. In particular, some of them can disrupt the metabolism of other medications. Contraception is another medication. If its metabolism was disrupted without your realizing it, that could be very bad. Be careful. If you’re taking other medications, tell your doctor about any supplements you’re taking. Don’t take supplements without a doctor’s okay if you have liver damage, kidney damage, or any chronic medical condition.

And with that stirring recommendation, here are some supplements that seem promising for depression, in approximate order of recommendedness.

1. S-Adenosyl methionine (SAM-e)

This would be my first choice if you’re trying to treat depression with supplements. It has a good evidence base, big effect size, it’s pretty safe, and it’s available on Amazon for $20 a jar. It probably works both on its own and as an adjunct to antidepressants, although there’s only partial evidence for the first claim. One experiment got good results with 800 mg two times a day for six weeks, though aside from that proper dosage is anyone’s guess.

2. Creatine

Yes, the same stuff bodybuilders use. One RCT found good results at 5g per day. May be more effective in people likely to be protein-deficient (eg vegetarians) and possibly in women.

3. Folate or l-methylfolate

Folate is a form of Vitamin B9 that most people get in food. Several RCTs have found positive effects from supplementing antidepressants with folate, although the evidence for folate on its own is still lacking. Some people with a mutant version of a gene called MTHFR are unable to process folate very well, and may get better results from an “optimized” version called l-methylfolate. A psychiatric medication commonly prescribed for treatment-resistant depression, Deplin, is l-methylfolate, but the supplement version is exactly the same. 5 – 15 mg / day seems to be a common dose, even though a lot of the supplements seem to contain a lot less.

4. Saffron

Yes, the spice. I’d never even heard about this until I checked examine.com, but it seems to check out. Five different randomized controlled trials found saffron to be more effective than placebo and as effective as conventional antidepressants. Amazon seems to be flooded with sellers ever since Dr. Oz apparently said it might be a weight loss supplement. [some problems, especially for pregnant women]

5. Fish oil

A lot of people are very excited about this, including examine.com. I’m more skeptical. There have been a lot of studies that suggest fish oil can improve mood in depression, and a lot of others that find no effect. And fish oil is a complicated supplement to deal with – most of the commonly sold pills don’t have enough to do any good, and if you don’t store it right it goes rancid and is worse than nothing.

Instead, I would eat a lot of fish. The degree to which the level of depression in a country correlates with the amount of fish eaten in that country is staggering. Two salmon dishes a week ought to be a good start.

6. -afinil

Modafinil is a wonder drug that gets used for everything, both legally (with prescription) and illegally (without). It was only a matter of time before someone tried it for depression, and it seems to work pretty well, at least as an adjunct to antidepressants. There are fewer studies about whether it works on its own. I would guess that it does, because the most likely mechanism is its well known tendency to increases energy and alertness, which is pretty useful against depression’s fatigue and tiredness. The strongest argument against modafinil is that it lacks a plausible mechanism for antidepressant action and so realistically you’re probably just treating symptoms. The strongest argument for is that you’re probably treating symptoms very well. Also worth noting that modafinil disturbs sleep and disturbing sleep is very bad in depression, so take it at the beginning of the day and if you still can’t sleep at night, cut the dose.

Modafinil is illegal without a prescription, but everyone on the Internet sells it anyway. Adrafinil is a prodrug that turns into modafinil once in the body. It is perfectly legal without a prescription, because the medical licensing regime makes no sense. You might as well just get that – as far as I can tell the risk of liver damage is overhyped if your liver is otherwise healthy.

7. Other things

Things I find interesting but which have conflicting evidence and/or don’t deserve a whole paragraph of their own include: lithium orotate microdosing, rhodiola, vitamin D, zinc, and curcumin. Look them up and see what you think.

Not exactly a supplement, but I’m pretty sure you can get Botox without a prescription, and if done correctly it might help substantially.

What if you want to buy antidepressants illegally without prescription?

Well, you probably won’t get caught. And you probably won’t kill yourself if you go into it semi-well-informed. I can’t in good conscience recommend it, but I’m sure it’s something a lot of people think about. Consider yourself scowled at, and at least take the following advice:

Definitely definitely do not take any tricyclics (hint: if it ends in -pramine, it’s a tricyclic) without a prescription. Those are seriously potentially dangerous. Taking MAOIs (phenelzine, tranylcypromine) without a prescription is the worst idea and you will die (note: some over the counter supplements claim to work through “MAOI-like action” or “being reversible MAOIs”. As far as I can tell these are safe, though I can’t vouch for their efficacy. Just don’t take the real thing.) I don’t even think anyone sells antipsychotics without prescription, but also the worst idea. If you are thinking of buying any of these without prescription, and you won’t accept advice to not buy prescription medications at all, can I at least talk you down into buying an ordinary relatively harmless SSRI?

For weird political reasons, tianeptine, a well-regarded foreign antidepressant, is not a prescription drug in the United States. I think it is still illegal, but everyone sells it all over the Internet, even respectable sites that wouldn’t dare sell the normal prescription antidepressants. It has a large Internet fan club that swears by it, and its side effects are less than those of many other antidepressant classes. It is available from nootropicsdepot, a supplier I regard pretty highly. If you can’t just buy normal supplements from a health food store like a normal person, it is very likely your best bet.

V. Other things

The average length of an untreated depressive episode is six months. People who have one depressive episode have an 80% chance of having another sometime in their life. The average person with major depressive disorder gets four depressive episodes during their lifetime. Take these statistics into account when deciding how proactive you want to be with treatment.

People with depression have about a 2% chance of going on to commit suicide, though obviously this varies a lot with the intensity of depression. Most people who attempt suicide later regret it and go on to live enjoyable lives. If you are feeling suicidal, there are suicide hotlines operating both by phone and by online chat. You can also go to any emergency room and ask for help. If you have health insurance, this will probably be covered. Warning: this will quite possibly result in committment to a psychiatric hospital.

If you are feeling very suicidal and don’t trust yourself not to attempt something, going to a psychiatric hospital is probably your best bet. The average length of stay at an average hospital is three to seven days. Two weeks is rare. A month is totally unheard of. You usually get intense attention from doctors, nurses, and social workers, and there are strict regulations giving you certain rights (ie you can’t be denied necessities of daily living and you can’t be locked up in any kind of restraints or solitary confinement without extremely good documentation that you are very dangerous). Psychiatric patients cannot be given non-emergency medication or other treatment against their wishes without a court order; psychiatrists are usually very good at pressuring patients to take medications in some kind of tricky ways, but in practice few of them will go through the difficulty of trying to get the court order unless the patient is extremely dangerous. People who complain about psychiatric hospitals most often complain that they are noisy (true), that they can’t leave when they want to (true), and that they are around some scary people (true, though very few are actually violent). Good psychiatric hospitals will have procedures in place for trying to minimize these problems; for example, there is a big movement to switch to private rooms. In my experience most suicidal depressed patients who go to a psychiatric hospital become less suicidal very quickly, end up on a good regimen of appropriate antidepressant medication, and are glad they went.

About a third of patients will recover completely on their first antidepressant within three months. Another third will get somewhat better (>50% decrease on some test of depressive symptoms). Another third will have no benefit.

But outcomes get better the more stuff you try. According to STAR*D, which tested an algorithm a lot like the one I mentioned above, by the last step of the algorithm 70% of patients experienced complete remission, and many more experienced significant symptom reduction.

This is not a resounding victory, because the average depressive episode only lasts six months and the study took more than six months to complete, which makes it really hard to figure out how much of the improvement was due to the drugs. The answer appears to be “some, maybe”. But I will add that patients who recovered because of the study drugs had decreased chance of relapse compared to patients who recover by waiting it out.

I think the important lesson here is that with sufficient work depression either is treatable, or it will go away on its own before you get a chance to finish the treatment algorithm, which is annoying for researchers but probably pretty acceptable to the patient. And once it does, you know what drug works for you, you can sometimes stay on it to decrease chance of relapse (maintenance treatment is a totally different ball game I’m not getting into here) and you can restart first thing when you start feeling depressed again.

The most important thing I’m writing this for, and the lesson I want to hammer home, is that if your doctor just gives you an SSRI and tells you to stay on it even when it clearly isn’t working, there are other options. If your depression is seriously impacting your life, you should explore them, either with your doctor or with a replacement doctor who is more willing to help or – if necessary – on your own.