Shared posts

3 Things You Need to Know About Sleep

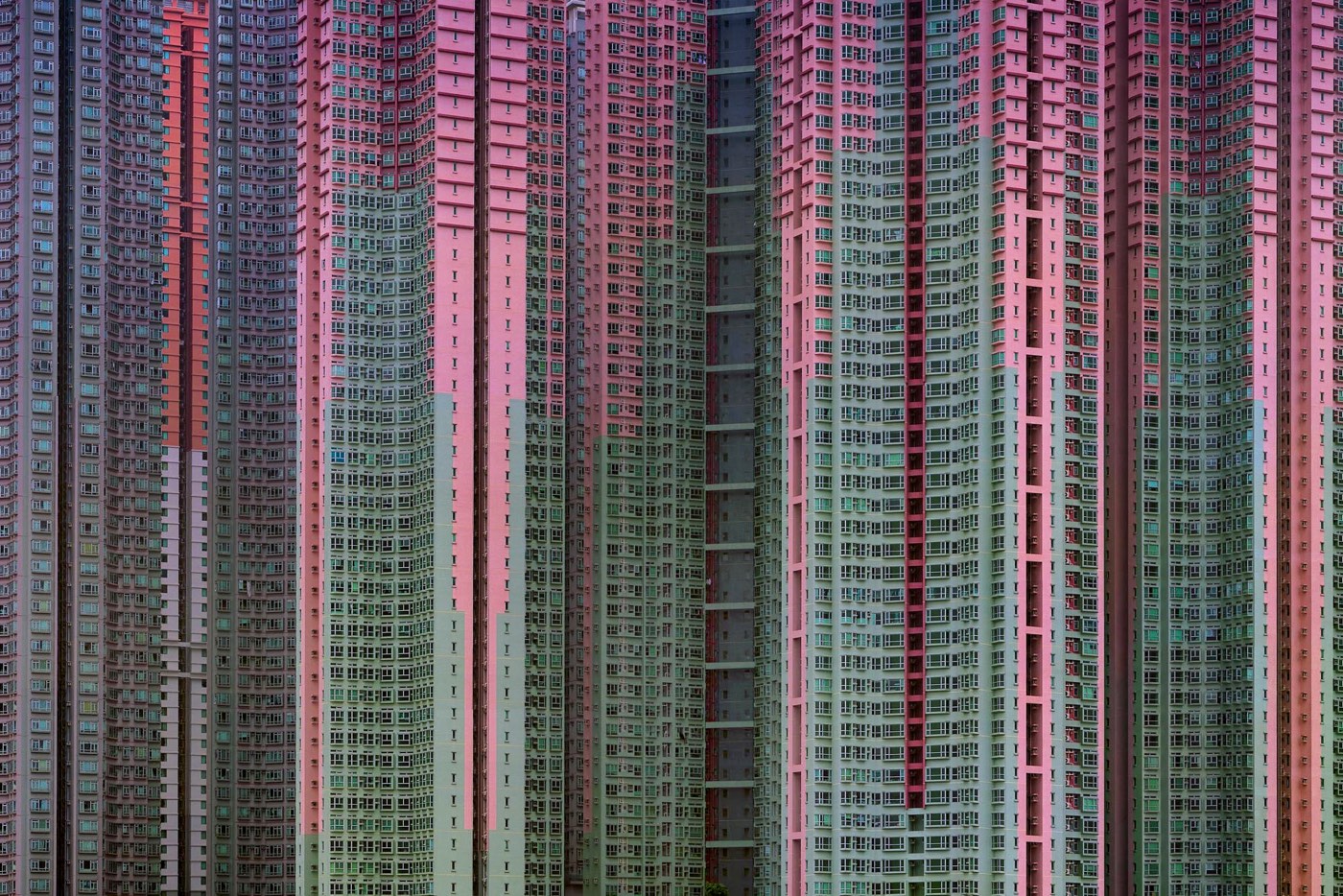

The dazzling and depressing architecture of density in megacities

I’ve featured the work of photographer Michael Wolf here before, particularly his series of photos taken in Hong Kong called Architecture of Density, photographs which capture the immense scale of the city’s apartment buildings and the smallness of the apartment they contain. Another of his projects is 100x100, interior photographs of 100 Hong Kong dwellings that measure 100 square feet or less in size. (See also Hong Kong Cage Homes.)

In this pair of videos, Wolf discusses these projects and a couple of other ones I hadn’t seen before.

In Tokyo Compression, Wolf captures the boredom and despair of Japanese train commuters, smushed into cars dampened by the heat of humanity. For Back Door, he ventured into the alleys of Hong Kong and witnessed people using the infrastructure of the city for storing, sorting, and drying all sorts of things, from after-work clothes to mops to lettuce. (via craig mod)

Tags: cities Hong Kong Michael Wolf photographyThe Static Speaks My Name Second Opinion

It Does One Thing Well

HIGH I have never seen the difficulty of doing basic things while depressed dramatized so well.

LOW The ten-minute play time doesn't leave room for much else.

WTF Wait—there was a story? Like, a real story?

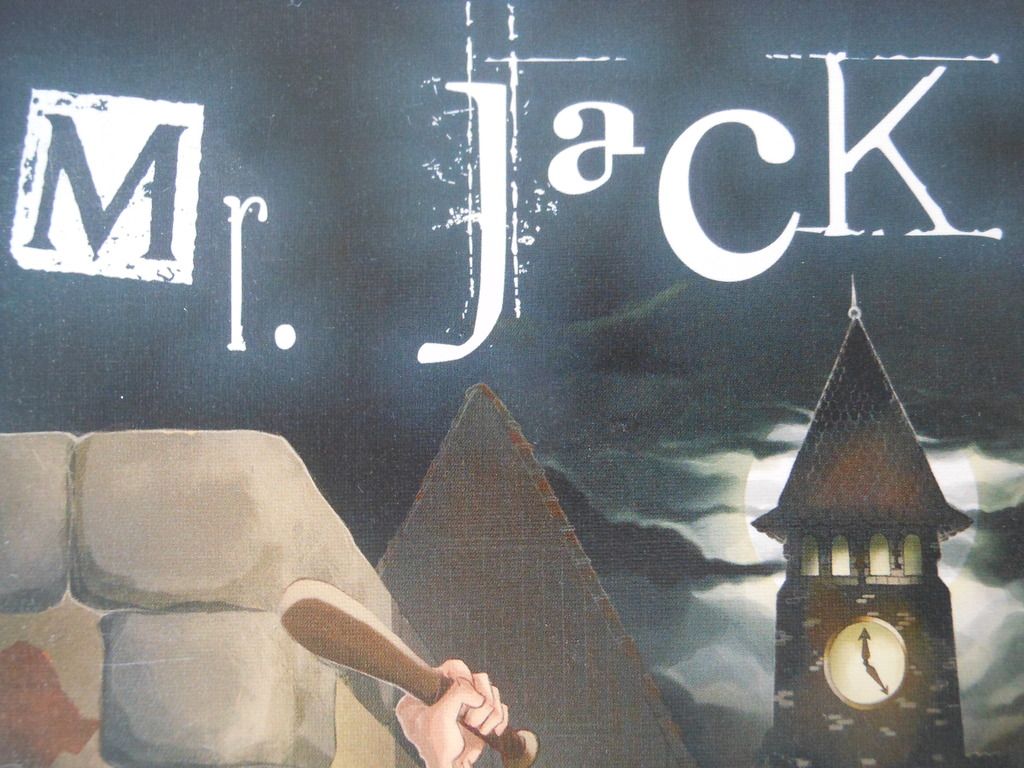

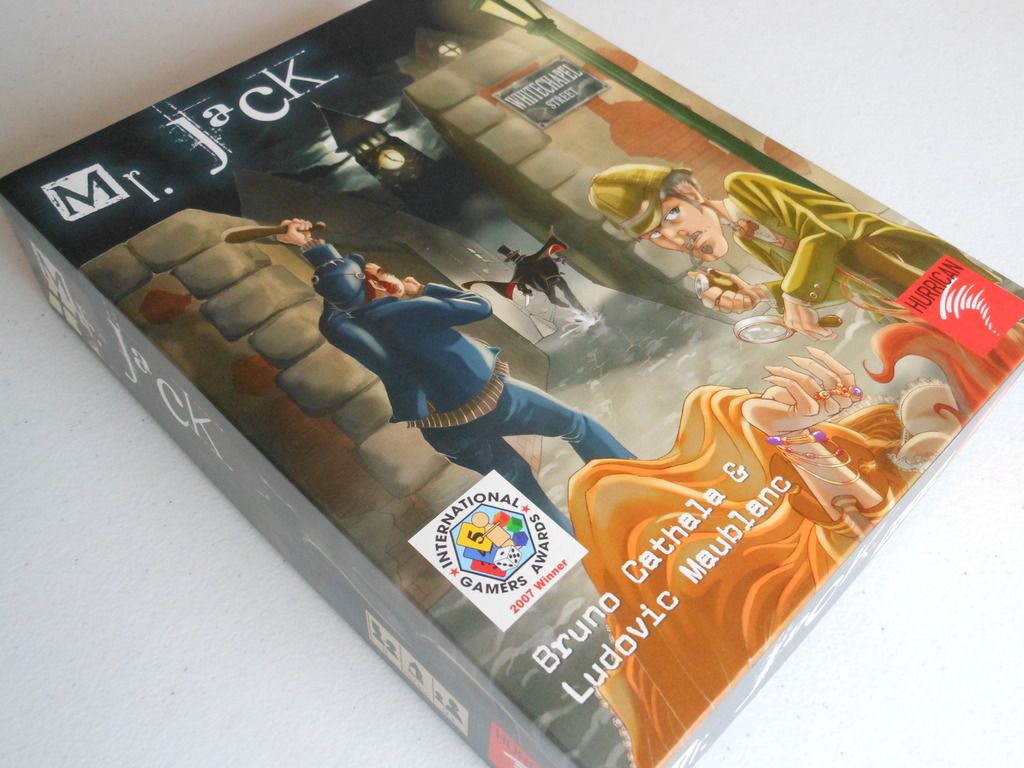

Mr. Jack

Mr. Jack

Published by Hurrican

Designed by Bruno Cathala and Ludovic Maublanc

For 2 players, aged 9 to adult

Everybody has a line.

You know, that line in the sand. The point of no return, when something becomes intolerable.

It's different for every person, and it isn't always rational.

The line is a personal thing, and sometimes people aren't really able to explain why the line is where it is. Some people don't even know they have a line until someone else crosses it. Or maybe even when they cross it themselves.

But, and here's the important bit... Nobody's line is in the right or wrong place. And nobody has the ability to move their line.

The line works on an emotional level. If something offends someone, they can't simply choose not to be offended. They aren't wrong for being offended.

Because the line is about a gut feeling. And guts are complicated.

I have a line.

It's not a straight line. It twists and turns like a twisty-turny thing, and I freely admit I don't understand it.

It is the line that allows me to sit through a game of Cards Against Humanity (disliking every minute of it), but which makes me feel incredibly uncomfortable at the thought of playing Freedom: The Underground Railroad.

It is the line that means I can happily play war games that recreate real life conflicts in which thousands of people lost their lives, but which makes me feel a bit icky about Paolo Parente artwork.

Recently, a game appeared on Kickstarter called Lobotomy. It looked pretty cool, with a dark, Gothic horror style and an intriguing premise. And for a little while I was vaguely interested, until I noticed it had inadvertently tripped over my line.

You see, as far as I can gather, the players each take on the role of a psychiatric patient attempting to escape an asylum. During the game, the players fight monsters, but... they're not really monsters. They are only perceived as monsters. They are actually the orderlies and nurses, attempting to return the mentally ill patients to their ward.

So, effectively it's a game about mentally ill people murdering their carers.

At least, that's how it seemed to me.

Perhaps I got the wrong end of the stick a bit. It doesn't matter. There is so much about the theme I find distasteful, there is no way I am ever going to buy the game.

Mental health problems are not entertainment.

But that's just my feelings. My line. And just because I feel that way, it doesn't mean the game shouldn't exist. It doesn't mean the people who supported its creation are bad people. Indeed, I would never call for the game to be banned.

I am well aware my line is mine, and mine alone.

Here's another example...

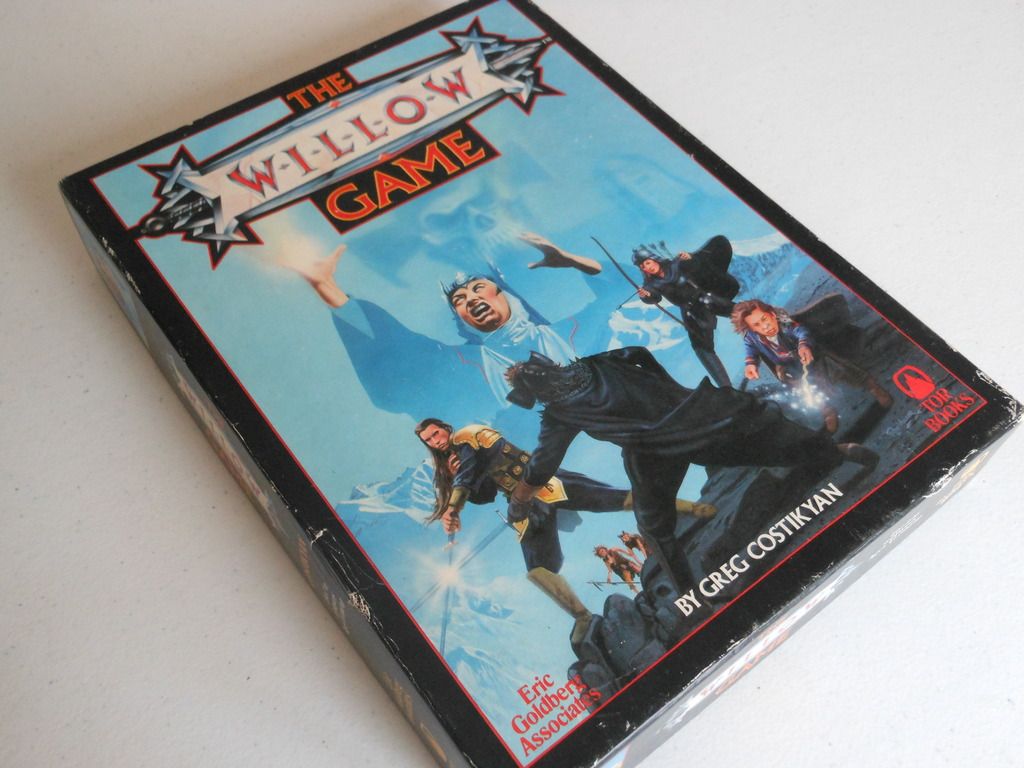

A few years back, I bought my wife a copy of the old 1988 board game, Willow. I picked it up on eBay for next to nothing. It was complete, and in beautiful condition. Slight wear on the box, but otherwise unused. A real find.

|

| Check it out - it's Val Kilmer. |

I bought the game because my wife is a huge fan of the movie. Because obviously her line is much further away than mine.

So, I gave my wife the game, and she was delighted. It's a cute little adventure game. Some players are good, controlling heroic characters as they move around a truly ugly board finding equipment and generally being heroic, and other players are evil, and get to work for Bavmorda.

|

| Good God. The colours. The colours. |

For anyone who has seen Willow, alarm bells should be ringing at this point.

You see, in the movie, Bavmorda is attempting to find a baby in order to kill her. So, the players controlling the evil characters in the board game are... well... they're attempting to find a baby in order to kill her.

Okay, okay. The rules gloss over it a bit. They never say your aim is to kill a baby. The rule book says you have to find the baby card, take it to your castle space, and then "remove it from play." But it is what it is... And what it is, is a game about murdering a baby.

And that's a no sale.

As it stands, we have never played this game, and I am not sure we ever will.

I know it's only a board game. I know that the people involved are not really killing a baby. I know it's irrational. I know...

But I can't play a game where my objective is to kill a child.

I can, however, happily play a game in which I assist one of history's most infamous serial killers.

Lines are funny that way.

The game, of course, is Mr. Jack, an incredibly clever and slickly designed board game for two players, in which one player attempts to sneak Jack the Ripper out of London, while the other player is the detective attempting to bring the ne'er-do-well to justice.

|

| Now, the cover art really is getting close to my line... |

So, how come I won't play a game about a fictional character killing a fictional baby, but I am happy to play a game based on a real life murderer who killed real people?

It's a good question.

For me, it is all about the degrees of separation.

If Mr. Jack was a game in which one player took on the role of Jack the Ripper, moving around the streets of London in secret, scoring victory points for every prostitute murdered, I would find the game utterly repulsive.

But that isn't what Mr. Jack is.

First, Mr. Jack is quite abstract, and involves moving wooden discs around a stylised map of Whitechapel. Second, at no point does Jack kill anyone; he is simply attempting to escape. But most importantly of all, neither player is asked to specifically step into the role of the serial killer. Indeed, at different points during the game, both players may have the opportunity to move Jack on the board. It clearly delineates fact and fiction, game and reality. It defines a barrier between emotion and logic.

This is not a roleplaying experience.

|

| Heroes or villains? |

Mr. Jack is an intense, head-to-head experience, using mechanisms that encourage players to focus on the challenge, rather than the theme.

The Jack player doesn't feel any more like Jack than a chess player feels like a bishop... Assuming the chess player isn't actually... you know... a bishop.

The concept of Mr. Jack is incredibly simple: At the start of the game, there are eight characters on the board. The Jack player draws a card that indicates which of the eight characters is Jack in disguise, and then one player shuffles a deck of eight character cards and lays out four face-up.

|

| Innocent or guilty? |

The detective player gets to pick one of the four face-up character cards, and then moves that character on the board. The Jack player picks two characters, and then the detective player uses the remaining character.

After four characters have moved, a gaslight may go off, plunging an area of the board into darkness, and then the detective player asks the Jack player if Jack is visible. If the token representing Jack is adjacent to a gaslight, adjacent to any other character, or within the beam of Dr.Watson's torch, then he is visible. Otherwise, Jack is hidden.

Next, the remaining four cards are laid out, and the process is repeated, except Jack picks the first character, then the detective player picks two characters, with the Jack player taking the last character.

This continues for eight rounds, until Jack is captured, or until Jack leaves the board.

When moving characters, players are attempting to do different things. The Jack player wants to move Jack off the board, but for this to happen, Jack must have been hidden from sight at the end of the previous turn. The detective player wants to keep Jack visible so he can't escape, but also wants to rule out suspects by keeping some characters visible while other characters are hidden.

|

| Ah, London... Where the streets are paved with hexagons. |

For example, if at the end of the round, the detective has managed to keep four character's visible while four characters are not visible, and then the Jack player says Jack is visible that round, the detective player is immediately able to determine that the four characters that are not visible are no longer suspects.

At any point, the detective player has the ability to move a character on top of another character to make an accusation. If the accused character is Jack, the detective wins; otherwise, Jack wins. Jack also wins by escaping the board, or remaining unchallenged for eight turns.

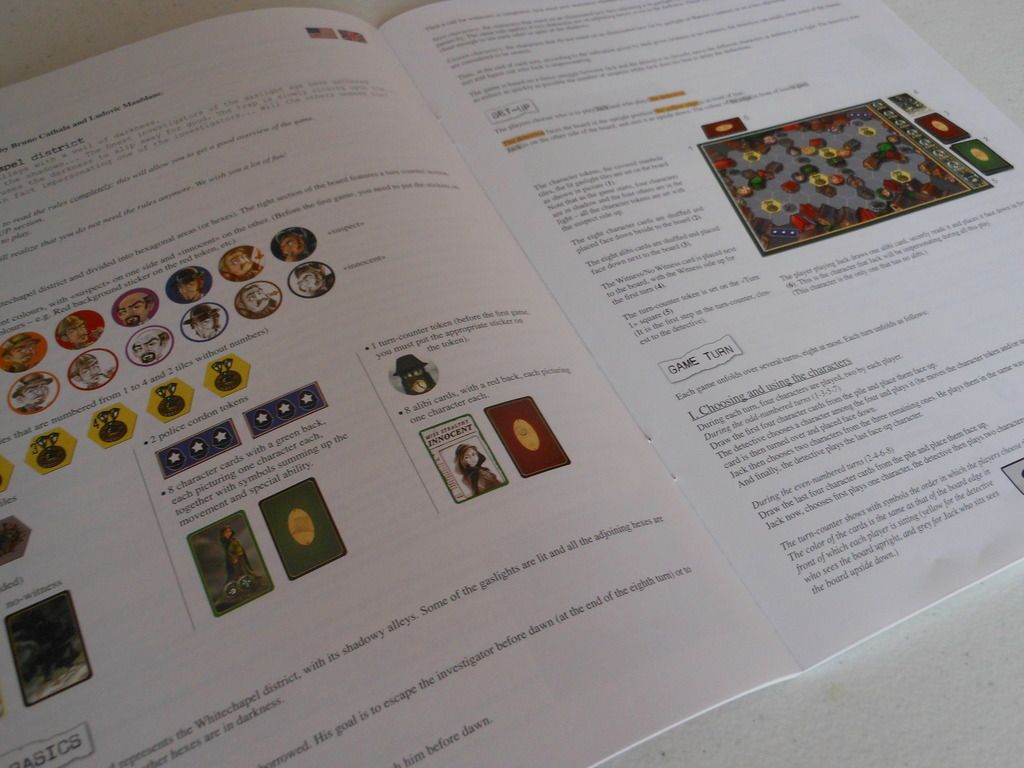

The game is incredibly simple. It is possible to teach the rules to a new player in a couple of minutes, but there is plenty of depth and strategy to enjoy, much of which derives from the special abilities of the characters, which range from the ability to move manhole covers to stop characters accessing the sewers to blowing on a whistle to draw surrounding characters closer.

|

| The rules are three pages long, and not as intimidating as they look. |

It's all very clever, and very clean. Clinical, almost. There is no bloat. No saggy rules. No fiddly tokens. No clutter.

Just you, and your opponent, locked in a battle of wits as you frantically move the same eight characters around the board in a furious game of cat and mouse.

It is very special, and beautifully presented.

And I never play it.

Well... hardly ever.

|

| Holmes is on the case... Or maybe he's Jack in disguise. |

My wife hates the game, which is a big problem as two player games are usually reserved for playing with my wife.

Not sure why she hates it. She just does.

Normally she loves games that are incredibly streamlined and quick, with simplistic rule sets but lots of strategic depth.

But not this one.

I occasionally roll the game out with friends, but I get the impression they don't really like it as much as I do.

And it's a shame, because you need to play this game a lot to get good at it. Sure, you can learn how to play in five minutes, but your first experience is not a true reflection of what the game has to offer.

You need to face the same opponent time and time again to build a rapport. You need to be able to read your enemy, call the bluffs, and really drill into the psychology behind each move. So, perhaps this is more of a roleplaying game than it appears at first... Because without the tension of two long-established foes locked in a battle of wits, you are just pushing wooden discs around a board, and that clinical rule set starts to feel more than just clean.

It starts to feel cold.

It starts to feel empty.

And that's where I have to draw the line.

I Am Bread Review

All Bun and Games

HIGH Zero-G mode.

LOW The game crashing while trying to load zero-G mode.

WTF The whole thing, really. It's a game about a slice of bread.

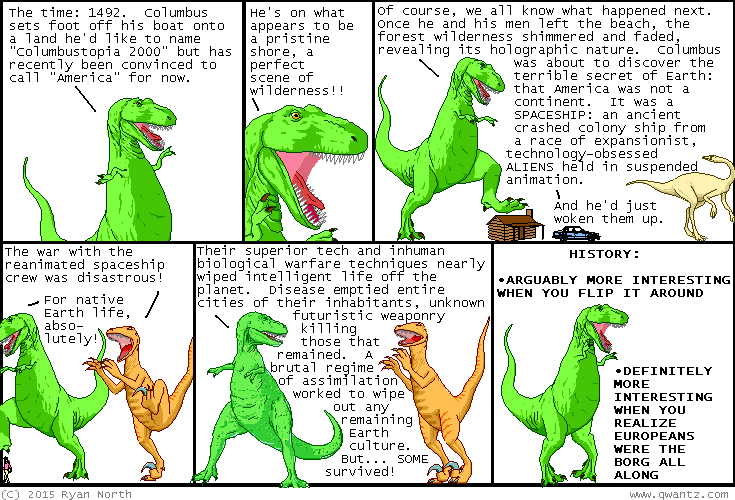

"the best of new worlds"

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | January 13th, 2015 | next | |

|

January 13th, 2015: I got a lot of emails asking to turn this comic into a t-shirt! And I was like, man, there's a lot of different ways that could be done! So I made THREE DIFFERENT VERSIONS, and for THIS WEEK ONLY, you can get them all! Right here. But the catch is they're all competing to become the REAL shirt, and you've only got seven days to get the one you want!    – Ryan | |||

"starfleet" was the only word in this comic that spell-check didn't recognize. i fixed that.

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - cute - search - about | |||

| dinosaur comics returns monday!

|

|||

| ← previous | October 17th, 2013 | next | |

|

October 17th, 2013: Janek sent me this early comic translated into Toki Pona, which is amazing. Toki Pona is a constructed language I'd never encountered before (Wikipedia says it has 3 people who are fluent) but I kind of love it: it's designed to be simple but still allow you to express complex thought. Check it out: there's five names for colours in Toki Pona (describing black, white, yellow, blue, and red - in other words, the CYMK colour space) and you can describe other colours by combining these two colours together like you would paints. Green is a "bluish yellow". This is totally rad! One year ago today: who wrote panel three, that's gross, i don't want to take credit for that – Ryan

| |||

‘BioShock Infinite’ And The Problem With Video Game Violence

Chad Urso McDanielI'm playing through Infinite now and feeling much of the same: Great game & a bit too much of the combat. I do think some of the violence is a bit much for my tastes.

BioShock Infinite has been widely criticized as too violent, but violence isn’t necessarily the problem.

[Spoilers follow.]

There seems to be a growing consensus that BioShock Infinite is too violent.

I’m going to both agree and disagree.

But before I tell you why, let’s take a look at what others are saying:

“I’m not saying that we should eliminate large scale combat from games. As I’ve said, titles like Halo and Gears and God of War are built on it, and it fits somewhat logically into the universe. But you have to recognize when it just comes off as goofy. If you’re trying to make a game about a teenage girl surviving an impossible situation, you sort of lose that concept when you have her execute mercenaries by the hundreds. When your game is BioShock Infinite, the pinnacle of design and thoughtfulness in the video game realm, exploding heads and gnarled faces don’t need to be the main staple of gameplay. I said in my initial review that I would have much rather used my litany of Vigor powers to solve puzzles rather than cook people alive, as that seemed far more in line with the tone of the game.”

“There are really two issues here: The fact that Infinite is a shooter, and the extremity of the violence it depicts. The further I get from the game and the more I replay it, the clearer it becomes: BioShock Infinite is a daring, audacious game held back by its reliance on the gun in the middle of the screen. What if it had been a first-person exploration and adventure game? What if there had been less shooting, and more puzzles and traversal? What if Booker had been more of an actual private investigator, rather than a commando for hire?

“And even if we accept that Infinite had to be a first-person shooter, did it really need to be this violent? It makes sense to create some awful sort of counterpoint to the opulent brilliance of Columbia, to frame shocking violence against the bright blue skies and breathtaking vistas. But the violence here, in the melee kills in particular, just doesn’t quite work. It feels indulgent and leering, like a concession to a perceived audience that may not even exist. Who really wanted sick badass head-trauma in this game? Not me, anyway.”

“Violence doesn’t serve BioShock Infinite. It distracts from it.

“Levine has been outspoken about his ambition to please both the meathead and the brainiac since the release of the original BioShock. But what about my wife? What about the people who can stomach only so much aggressive violence and unchecked cruelty? Defenders of the game’s violence have compared BioShock Infinite to Christopher Nolan’s Batman movies, which melded together the cerebral indie aesthetic and the mind-numbing blockbuster spectacle. But every comic lover knows the difference between Booker DeWitt and Batman. Batman doesn’t kill people.”

“So, the guy that brought you a chainsaw gun would now like to get on his soap box about violence. Have fun judging me.

“This is one of the few games that I’ve loved that I felt the violence actually detracted from the experience. The first time I dug my skyhook into someone I actually winced. I love shocking people in these games (it’s not called BioShootBeesAtThem) and I found that nearly every foe I zapped to death had their heads explode, Gallagher style. After the 400th head I was like “come on, already!”

“Funny, right? That I’d say that? I know, it’s weird. Maybe it’s the fact that they did such a fantastic job of making this nuanced world that hitting you over the head with those moments felt out of place for me.”

~Cliff Bleszinski, via his blog

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Like I said, I both agree and disagree.

I actually don’t think the moments of ultra-violence in the game are what make it problematic. After all, those moments have the potential to be gripping, powerful bits of gameplay that shock us out of our reverie as we gaze in wonder at the lovely architecture of Columbia.

No, the real problem with BioShock Infinite is that it’s too focused on combat. It could be the least bloody combat in the world and it would still be a problem. And it’s not just a problem with BioShock Infinite, it’s a problem with a lot of games recently, like Tomb Raider and Spec Ops: The Line and Black Ops II. The list goes on and on.

I’m someone who tends to really likes combat in video games, and isn’t bothered by all the ultra-violence, and who views the entire act of video game combat as a sort of moving puzzle and still…

The problem with Infinite is that there’s entirely too much killing going on throughout the game, and all that killing ends up destroying pacing and numbing us to the really powerful moments of horror, not because it’s too violent but because it’s too constant.

You see, I wouldn’t want to lose that first skull crushing scene. It’s shocking and it should be. It’s that the next thirty, fifty, or two hundred corpses that start to pile up and get in the way and pretty soon the dialogue between Elizabeth and Booker starts to sound a little ridiculous.

The crow-men are pretty horrific, also, and one of the best enemy types in the game. The first time you encounter them you see a man basically ripped to shreds by murderous crows, and that’s a great, scary moment. Keep that. Keep the gruesome stuff because it makes the game dark and scary and wonderful.

The real problem is that these moments are sprinkled throughout a game that’s devoted mostly to shooting wave upon wave upon bloody wave of enemies.

Actually, it’s funny to me that BioShock Infinite sparks this discussion, because it’s hardly a new problem. Maybe it’s because Infinite is such a smart game in so many ways, it illuminates the problem more brightly than most.

Of course, Tomb Raider should have been a game about climbing and solving puzzles, and instead it was very much like Infinite in its ability to turn the hero, Lara Croft, into a mass murderer of epic proportions. Booker DeWitt tells Elizabeth that he isn’t afraid of God, but he’s afraid of her. Elizabeth is nothing compared to the cold-blooded killer that is Lara Croft.

Even in games that purport to critique game violence we have this problem.

Both Spec Ops: The Line and Far Cry 3 are attempts at portraying violence in video games as bad. But instead of making that violence profound and impactful, they give us myriad hordes of badguys to thoughtlessly, remorselessly slaughter. Both games have moments, like BioShock Infinite, that are appallingly violent, but those moments are just as diluted by the rest of these games’ mass killing.

It was actually Far Cry 3 that made me want a game that was more lonesome and less kill-happy, or that made me so starkly aware of that desire. I was annoyed that the island I was on was so heavily populated. I was just as annoyed that there were so many dozens of pirates and that I could kill them all despite my character’s total inexperience with killing and fighting.

I imagined an island in which I was truly out to survive, where the enemies would be the hunters and I would have to outwit them. In other words, a totally different game. That game could have been horrifically violent and still not focused so much on this boring, tedious sort of combat that the shooter genre has embraced.

In Spec Ops: The Line, the game’s various horrific revelations could have been so much more profound if my character wasn’t just another super soldier the entire game, or if the game slowly devolved from a more restrained shooter into one that was clearly a man’s delusions.

Violence in film can be stupid and mindless at times, but it’s rarely ever as stupid and mindless as even the smartest video games. I can’t imagine watching an Indiana Jones movie that consisted of Indiana just mowing down enemies with a chain gun or splattering skulls all over the place. But certain scary moments in those films, where the violence is suddenly pronounced, still work just fine.

BioShock Infinite needed to be a first-person shooter. It needed to have shooting and violence. It would have been weird to lose that stuff. What it should have done is allow that shooting and violence to be more brief, more meaningful, and ultimately more in keeping with the rest of the game’s polish and refinement—not because it was too violent, but because all that shooting is getting boring and silly at this point.

Add in more platforming, more puzzling, more challenge beyond the fighting, and you have a pretty perfect gaming experience, regardless of how violent it is.

Ultimately, like much of the sexism we see in video games, this is a failure and of storytelling in the medium. It may be that we notice it so much in BioShock Infinite because that game does such a good job at telling a story in almost every other way.

My hope is that other games that come out later this year, like The Last of Us, buck the trend a bit.

The Last of Us looks really violent, but I hope it’s less of a constant shooter than Naughty Dog’s Uncharted series. That franchise is one of the worst offenders, in my opinion: a story about a rakish explorer who goes from charming and care free one moment, to every bit as bloody and sadistic as Booker or Lara the next. I want the violence in The Last of Us to mean something, even if it’s just used to unsettle and frighten us.

Survival games tend to do this better than action games, so we may be in luck.

see photosIrrational Games

see photosIrrational Games