The Misconception: You should focus on the successful if you wish to become successful.

The Truth: When failure becomes invisible, the difference between failure and success may also become invisible.

In New York City, in an apartment a few streets away from the center of Harlem, above trees reaching out over sidewalks and dogs pulling at leashes and conversations cut short to avoid parking tickets, a group of professional thinkers once gathered and completed equations that would both snuff and spare several hundred thousand human lives.

People walking by the apartment at the time had no idea that four stories above them some of the most important work in applied mathematics was tilting the scales of a global conflict as secret agents of the United States armed forces, arithmetical soldiers, engaged in statistical combat. Nor could people today know as they open umbrellas and twist heels on cigarettes, that nearby, in an apartment overlooking Morningside Heights, one of those soldiers once effortlessly prevented the United States military from doing something incredibly stupid, something that could have changed the flags now flying in capitals around the world had he not caught it, something you do every day.

These masters of math moved their families across the country, some across an ocean, so they could work together. As they unpacked, the theaters in their new hometowns replaced posters for Citizen Kane with those for Casablanca, and the newspapers they unwrapped from photo frames and plates featured stories still unravelling the events at Pearl Harbor. Many still held positions at universities. Others left those sorts of jobs to think deeply in one of the many groups that worked for the armed forces, free of any other obligations aside from checking in on their families at night and feeding their brains during the day. All paused their careers and rushed to enlist so they could help crush Hitler, not with guns and brawn, but with integers and exponents.

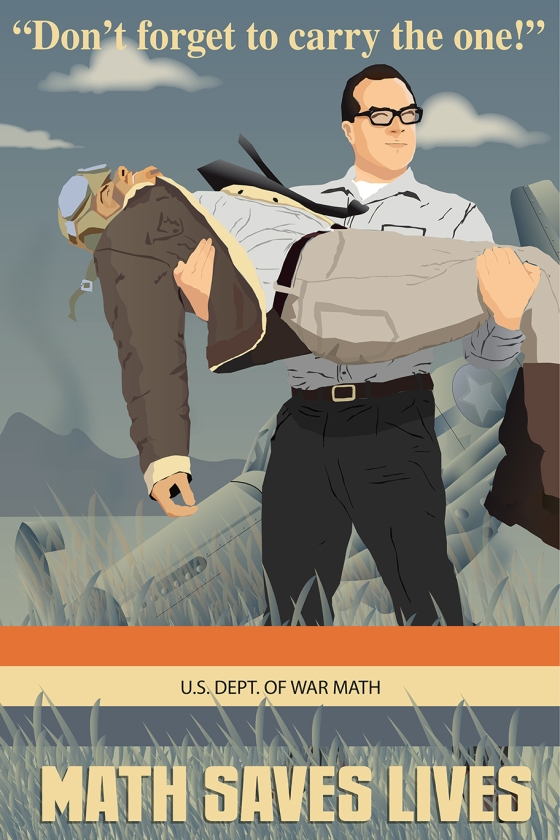

The official name for the people inside the apartment was the Statistical Research Group, a cabal of geniuses assembled at the request of the White House and made up of people who would go on to compete for and win Nobel Prizes. The SRG was an extension of Columbia University, and they dealt mainly with statistical analysis. The Philadelphia Computing Section, made up entirely of women mathematicians, worked six days a week at the University of Pennsylvania on ballistics tables. Other groups with different specialties were tied to Harvard, Princeton, Brown and others, 11 in all, each a leaf at the end of a new branch of the government created to help defeat the Axis – the Department of War Math.

Actually…no. They were never officially known by such a deliciously sexy title. They were instead called the Applied Mathematics Panel, but they operated as if they were a department of war math.

The Department, ahem, the Panel, was created because the United States needed help. A surge of new technology had flooded into daily life, and the same wonders that years earlier drove ticket sales to the World’s Fair were now cracking open cities. Numbers and variables now massed into scenarios far too complex to solve with maps and binoculars. The military realized it faced problems that no soldier had ever confronted. No best practices yet existed for things like rockets and radar stations and aircraft carriers. The most advanced computational devices available were clunky experiments made of telephone switches or vacuum tubes. A calculator still looked like the mutant child of an old-fashioned cash register and a mechanical typewriter. If you wanted solutions to the newly unfathomable problems of modern combat you needed powerful number crunchers, and in 1941 the world’s most powerful number crunchers ran on toast and coffee.

Here is how it worked: Somewhere inside the vast machinery of war a commander would stumble into a problem. That commander would then send a request to the head of the Panel who would then assign the task to the group he thought would best be able to resolve the issue. Scientists in that group would then travel to Washington and meet with with top military personnel and advisors and explain to them how they might go about solving the problem. It was like calling technical support, except you called a computational genius who then invented a new way of understanding the world through math in an effort to win a global conflict for control of the planet.

For instance, the Navy desperately needed to know what was the best possible pattern, or spread, of torpedoes to launch against large enemy ships. All they had to go on were a series of hastily taken, blurry, black-and-white photographs of turning Japanese war vessels. The Panel handed over the photos to one of its meat-based mainframes and asked it to report back when it had a solution. The warrior mathematicians solved the problem almost as soon as they saw it. Lord Kelvin, they told the Navy, had already worked out the calculations in 1887. Just look at the patterns in the waves, they explained, see how they fan out in curves like an unfurling fern? The spaces tell you everything; they give it all away. Work out the distance between the cusps of the bow waves and you’ll know how fast the ship is going. Lord Kelvin hadn’t worked out what to do if the ship was turning, but no problem, they said. The mathematicians scribbled on notepads and clacked on blackboards until they had both advanced the field and created a solution. They then measured wavelets on real ships and saw their math was sound. The Navy added a new weapon to its arsenal – the ability to accurately send a barrage of torpedoes into a turning ship based only on what you could divine from the patterns in the waves.

The devotion of the mathematical soldiers grew stronger as the war grew bloodier and they learned the things they etched on hidden blackboards and jotted on guarded scraps of paper determined who would and would not return home to their families once the war was over. Leading brains in every scientific discipline had eagerly joined the fight, and although textbooks would eventually devote chapters to the work of the codebreakers and the creators of the atomic bomb, there were many groups whose stories never made headlines that produced nothing more than weaponized equations. One story in particular was nearly lost forever. In it, a brilliant statistician named Abraham Wald saved countless lives by preventing a group of military commanders from committing a common human error, a mistake that you probably make every single day.

Colleagues described Wald as gentle and kind, and as a genius unsurpassed in his areas of expertise. His contributions, said one peer, had “produced a decisive turn in method and purpose” in the social sciences. Born in a Hungary in 1902 on a parcel of land later claimed by Romania, the son of a Jewish baker, Wald spent his childhood studying equations, eventually working his way up through academia to become a graduate student at the University of Vienna mentored by the great mathematician Karl Menger. He was the sort of student who offered suggestions on how to improve the books he was reading, and then saw to it those suggestions were incorporated into later editions. His mentor would introduce Wald to problems that made experts in the field rub their beards, the sort of things with names like “stochastic difference equations” and the “betweenness among the ternary relations in metric space.” Wald would not only return within a month or so with the solution to such a problem but politely ask for another to solve. As he advanced the science of probability and statistics, his name became familiar to mathematicians in the United States where he eventually fled in 1938, reluctantly, as the Nazi threat grew. His family, all but a single brother, would later die in the extermination camp known as Auschwitz.

Soon after Wald arrived in the United States he joined the Applied Mathematics Panel and went to work with the team at Columbia stuffed in the secret apartment overlooking Harlem. His group looked for patterns and applied statistics to problems and situations too large and unwieldy for commanders to get their arms around. They turned the geometry of air combat into graphs and charts and they plotted the success rates of bomb sights and various tactics. As the war progressed, their efforts became focused on the most pressing problem of the war – keeping airplanes in the sky.

In some years of World War II, the chances of a member of a bomber crew making it through a tour of duty was about the same as calling heads in a coin toss and winning. As a member of a World War II bomber crew, you flew for hours above an entire nation hoping to murder you while suspended in the air, huge, visible from far away, and vulnerable from every direction above and below as bullets and flak streamed out to puncture you. “Ghosts already,” that’s how historian Kevin Wilson described World War II airmen. They expected to die because it always felt like the chances of surviving the next bombing run were about the same as running shirtless across a football field swarming with angry hornets and making it unharmed to the other side. You might make it across once, but if you kept running back and forth, eventually your luck would run out. Any advantage the mathematicians could provide, even a very small one, would make a big difference day after day, mission after mission.

As with the torpedo problem, the top brass explained what they knew, and the Panel presented the problem to Wald and his group. How, the Army Air Force asked, could they improve the odds of a bomber making it home? Military engineers explained to the statistician that they already knew the allied bombers needed more armor, but the ground crews couldn’t just cover the planes like tanks, not if they wanted them to take off. The operational commanders asked for help figuring out the best places to add what little protection they could. It was here that Wald prevented the military from falling prey to survivorship bias, an error in perception that could have turned the tide of the war if left unnoticed and uncorrected. See if you can spot it.

The military looked at the bombers that had returned from enemy territory. They recorded where those planes had taken the most damage. Over and over again, they saw the bullet holes tended to accumulate along the wings, around the tail gunner, and down the center of the body. Wings. Body. Tail gunner. Considering this information, where would you put the extra armor? Naturally, the commanders wanted to put the thicker protection where they could clearly see the most damage, where the holes clustered. But Wald said no, that would be precisely the wrong decision. Putting the armor there wouldn’t improve their chances at all.

Do you understand why it was a foolish idea? The mistake, which Wald saw instantly, was that the holes showed where the planes were strongest. The holes showed where a bomber could be shot and still survive the flight home, Wald explained. After all, here they were, holes and all. It was the planes that weren’t there that needed extra protection, and they had needed it in places that these planes had not. The holes in the surviving planes actually revealed the locations that needed the least additional armor. Look at where the survivors are unharmed, he said, and that’s where these bombers are most vulnerable; that’s where the planes that didn’t make it back were hit.

Taking survivorship bias into account, Wald went ahead and worked out how much damage each individual part of an airplane could take before it was destroyed – engine, ailerons, pilot, stabilizers, etc. – and then through a tangle of complicated equations he showed the commanders how likely it was that the average plane would get shot in those places in any given bombing run depending on the amount of resistance it faced. Those calculations are still in use today.

1944 War Dept US Army Air Forces Training Film – Source: National Archives

The military had the best data available at the time, and the stakes could not have been higher, yet the top commanders still failed to see the flaws in their logic. Those planes would have been armored in vain had it not been for the intervention of a man trained to spot human error.

A question should be forming in the front of your brain at this point. If the top brass of the United States armed forces could make such a simple and dumb mistake while focused on avoiding simple and dumb mistakes, thanks to survivorship bias, does that mean survivorship bias is likely bungling many of your own day-to-day assumptions? The answer is, of course, yes. All the time.

Simply put, survivorship bias is your tendency to focus on survivors instead of whatever you would call a non-survivor depending on the situation. Sometimes that means you tend to focus on the living instead of the dead, or on winners instead of losers, or on successes instead of failures. In Wald’s problem, the military focused on the planes that made it home and almost made a terrible decision because they ignored the ones that got shot down.

It is easy to do. After any process that leaves behind survivors, the non-survivors are often destroyed or muted or removed from your view. If failures becomes invisible, then naturally you will pay more attention to successes. Not only do you fail to recognize that what is missing might have held important information, you fail to recognize that there is missing information at all.

You must remind yourself that when you start to pick apart winners and losers, successes and failures, the living and dead, that by paying attention to one side of that equation you are always neglecting the other. If you are thinking about opening a restaurant because there are so many successful restaurants in your hometown, you are ignoring the fact that only successful restaurants survive to become examples. Maybe on average 90 percent of restaurants in your city fail in the first year. You can’t see all those failures because when they fail they also disappear from view. As Nassim Taleb writes in his book The Black Swan, “The cemetery of failed restaurants is very silent.” Of course the few that don’t fail in that deadly of an environment are wildly successful because only the very best and the very lucky can survive. All you are left with are super successes, and looking at them day after day you might think it’s a great business to get into when you are actually seeing evidence that you should avoid it.

Google’s Larry Page – Source: Fortune Magazine

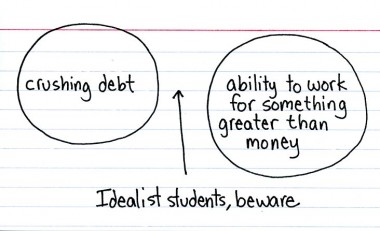

Survivorship bias pulls you toward bestselling diet gurus, celebrity CEOs, and superstar athletes. It’s an unavoidable tick, the desire to deconstruct success like a thieving magpie and pull away the shimmering bits. You look to the successful for clues about the hidden, about how to better live your life, about how you too can survive similar forces against which you too struggle. Colleges and conferences prefer speakers who shine as examples of making it through adversity, of struggling against the odds and winning. The problem here is that you rarely take away from these inspirational figures advice on what not to do, on what you should avoid, and that’s because they don’t know. Information like that is lost along with the people who don’t make it out of bad situations or who don’t make it on the cover of business magazines – people who don’t get invited to speak at graduations and commencements and inaugurations. The actors who traveled from Louisiana to Los Angeles only to return to Louisiana after a few years don’t get to sit next to James Lipton and watch clips of their Oscar-winning performances as students eagerly gobble up their crumbs of wisdom. In short, the advice business is a monopoly run by survivors. As the psychologist Daniel Kahneman writes in his book Thinking Fast and Slow, “A stupid decision that works out well becomes a brilliant decision in hindsight.” The things a great company like Microsoft or Google or Apple did right are like the planes with bullet holes in the wings. The companies that burned all the way to the ground after taking massive damage fade from memory. Before you emulate the history of a famous company, Kahneman says, you should imagine going back in time when that company was just getting by and ask yourself if the outcome of its decisions were in any way predictable. If not, you are probably seeing patterns in hindsight where there was only chaos in the moment. He sums it up like so, “If you group successes together and look for what makes them similar, the only real answer will be luck.”

If you see your struggle this way, as partly a game of chance, then as Google Engineer Barnaby James writes on his blog, “skill will allow you to place more bets on the table, but it’s not a guarantee of success.” Thus, he warns, “beware advice from the successful.” Entrepreneur Jason Cohen, in writing about survivorship bias, points out that since we can’t go back in time and start 20 identical Starbucks across the planet, we can never know if that business model is the source of the chain’s immense popularity or if something completely random and out of the control of the decision makers led to a Starbucks on just about every street corner in North America. That means you should be skeptical of any book promising you the secrets of winning at the game of life through following any particular example.

It might seem disheartening, the fact that successful people probably owe more to luck than anything else, but only if you see luck as some sort of magic. Take off those superstitious goggles for a moment, and consider this: the latest psychological research indicates that luck is a long mislabeled phenomenon. It isn’t a force, or grace from the gods, or an enchantment from fairy folk, but the measurable output of a group of predictable behaviors. Randomness, chance, and the noisy chaos of reality may be mostly impossible to predict or tame, but luck is something else. According to psychologist Richard Wiseman, luck – bad or good – is just what you call the results of a human being consciously interacting with chance, and some people are better at interacting with chance than others.

Over the course of 10 years, Wiseman followed the lives of 400 subjects of all ages and professions. He found them after he placed ads in newspapers asking for people who thought of themselves as very lucky or very unlucky. He had them keep diaries and perform tests in addition to checking in on their lives with interviews and observations. In one study, he asked subjects to look through a newspaper and count the number of photographs inside. The people who labeled themselves as generally unlucky took about two minutes to complete the task. The people who considered themselves as generally lucky took an average of a few seconds. Wiseman had placed a block of text printed in giant, bold letters on the second page of the newspaper that read, “Stop counting. There are 43 photographs in this newspaper.” Deeper inside, he placed a second block of text just as big that read, “Stop counting, tell the experimenter you have seen this and win $250.” The people who believed they were unlucky usually missed both.

Over the course of 10 years, Wiseman followed the lives of 400 subjects of all ages and professions. He found them after he placed ads in newspapers asking for people who thought of themselves as very lucky or very unlucky. He had them keep diaries and perform tests in addition to checking in on their lives with interviews and observations. In one study, he asked subjects to look through a newspaper and count the number of photographs inside. The people who labeled themselves as generally unlucky took about two minutes to complete the task. The people who considered themselves as generally lucky took an average of a few seconds. Wiseman had placed a block of text printed in giant, bold letters on the second page of the newspaper that read, “Stop counting. There are 43 photographs in this newspaper.” Deeper inside, he placed a second block of text just as big that read, “Stop counting, tell the experimenter you have seen this and win $250.” The people who believed they were unlucky usually missed both.

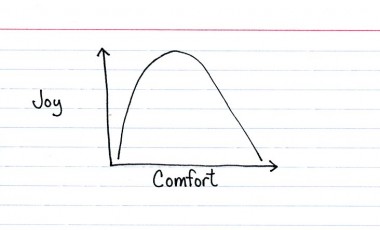

Wiseman speculated that what we call luck is actually a pattern of behaviors that coincide with a style of understanding and interacting with the events and people you encounter throughout life. Unlucky people are narrowly focused, he observed. They crave security and tend to be more anxious, and instead of wading into the sea of random chance open to what may come, they remain fixated on controlling the situation, on seeking a specific goal. As a result, they miss out on the thousands of opportunities that may float by. Lucky people tend to constantly change routines and seek out new experiences. Wiseman saw that the people who considered themselves lucky, and who then did actually demonstrate luck was on their side over the course of a decade, tended to place themselves into situations where anything could happen more often and thus exposed themselves to more random chance than did unlucky people. The lucky try more things, and fail more often, but when they fail they shrug it off and try something else. Occasionally, things work out.

Wiseman told Skeptical Inquirer magazine that he likened it to setting loose two people inside an apple orchard, each tasked with filling up their baskets as many times as possible. The unlucky person tends to go to the same few spots over and over again, the basket holding fewer apples each visit. The lucky person never visits the same spot twice, and that person’s basket is always full. Change those apples to experiences, and imagine a small portion of those experiences lead to fame, fortune, riches, or some other form of happiness material or otherwise, and you can see that chance is not as terrifying as it first appears, you just need to learn how to approach it.

“The harder they looked, the less they saw. And so it is with luck – unlucky people miss chance opportunities because they are too focused on looking for something else. They go to parties intent on finding their perfect partner and so miss opportunities to make good friends. They look through newspapers determined to find certain type of job advertisements and as a result miss other types of jobs. Lucky people are more relaxed and open, and therefore see what is there rather than just what they are looking for.” – Richard Wiseman in an article written for Skeptical Inquirer

Survivorship bias also flash-freezes your brain into a state of ignorance from which you believe success is more common than it truly is and therefore you leap to the conclusion that it also must be easier to obtain. You develop a completely inaccurate assessment of reality thanks to a prejudice that grants the tiny number of survivors the privilege of representing the much larger group to which they originally belonged.

Here is an easy example. Many people believe old things represent a higher level of craftsmanship than do new things. It’s sort of a “they don’t make them like they used to” kind of assumption. You’ve owned cars that only lasted a few years before you had to start replacing them piece by piece, and, would you look at that, there goes another Volkswagon Beetle buzzing along like it just rolled off an assembly line. It’s survivorship bias at work. The Beetle or the Mustang or the El Camino or the VW Minibus are among a handful of models that survived in large enough numbers to become iconic classics. The hundreds of shitty car designs and millions of automobile corpses in junkyards around the world far outnumber the popular, well-maintained, successful, beloved survivors. According to Josh Clark at HowStuffWorks, most experts say that cars from the last two decades are far more reliable and safer than the cars of the 1950s and ‘60s, but plenty of people believe otherwise because of a few high-profile survivors. The examples that would disprove such assumptions are rusting out of sight. Do you see how it’s the same as Wald’s bombers? The Beetle survived, like the bombers that made it home, and it becomes a representative of 1960s cars because it remains visible. All the other cars that weren’t made in the millions and weren’t easy to maintain or were poorly designed are left out of the analysis because they are now removed from view, like the bombers that didn’t return.

Similarly, photographer Mike Johnston explains on his blog that the artwork that leaps from memory when someone mentions a decade like the 1920s or a movement like Baroque is usually made up of things that do not suck. Your sense of a past era tends to be informed by paintings and literature and drama that are not crap, even though at any given moment pop culture is filled with more crap than masterpieces. Why? It isn’t because people were better artists back in the day. It is because the good stuff survives, and the bad stuff is forgotten. So over time, you end up with skewed ideas of past eras. You think the artists of antiquity were amazing in the same way you associate the music of past decades with the songs that survived long enough to get into your ears. The movies about Vietnam never seem include in their soundtracks the songs that sucked.

“I have to chuckle whenever I read yet another description of American frontier log cabins as having been well crafted or sturdily or beautifully built. The much more likely truth is that 99% of frontier log cabins were horribly built—it’s just that all of those fell down. The few that have survived intact were the ones that were well made. That doesn’t mean all of them were.” – Mike Johnston at The Online Photographer

You succumb to survivorship bias because you are innately terrible with statistics. For instance, if you seek advice from a very old person about how to become very old, the only person who can provide you an answer is a person who is not dead. The people who made the poor health choices you should avoid are now resting in the earth and can’t tell you about those bad choices anymore. That’s why it’s difficult not to furrow your brow and wonder why you keep paying for a gym membership when Willard Scott showcases the birthday of a 110-year-old woman who claims the source of her longevity is a daily regimen of cigarillos, cheese sticks, and Wild Turkey cut with maple syrup and Robitussin. You miss that people like her represent a very small number of the living. They are on the thin end of a bell curve. There is a much larger pool of people who basically drank bacon grease for breakfast and didn’t live long enough to appear on television. Most people can’t chug bourbon and gravy for a lifetime and expect to become an octogenarian, but the unusually lucky handful who can tend to stand out precisely because they are alive and talking.

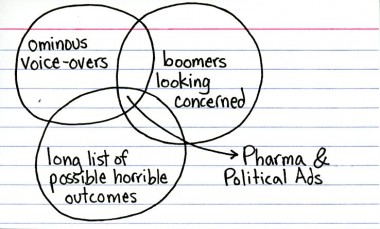

The mentalist Derren Brown once predicted he could flip a coin 10 times in a row and have it come up heads every time. He then dazzled UK television audiences by doing exactly that, flipping the coin into a bowl with only one cutaway shot for flair. How did he do it? He filmed himself flipping coins for nine hours until he got the result he wanted. He then edited out all the failures and presented the single success.

The mentalist Derren Brown once predicted he could flip a coin 10 times in a row and have it come up heads every time. He then dazzled UK television audiences by doing exactly that, flipping the coin into a bowl with only one cutaway shot for flair. How did he do it? He filmed himself flipping coins for nine hours until he got the result he wanted. He then edited out all the failures and presented the single success.

Advertisements for weight loss products and fitness regimens operate just like Derren Brown’s magic trick, by hiding the failures and letting your survivorship bias do the rest. “Those always use the most positive claims, the most outrageous examples to sell a product,” Phil Plait, an astronomer and leading voice in the skeptical movement, explained to me. “When these things don’t work for the vast majority of customers, you never hear about it, at least not from the seller.” The people who use the diet, or the product, or the pill, and fail to lose weight don’t get trotted out for photo shoots – only the successes do. That same phenomenon has become a problem in science publications, especially among the younger sciences like psychology, but it is now under repair. For far too long, studies that fizzled out or showed insignificant results have not been submitted for publication at the same level as studies that end up with positive results, or even worse, they’ve been rejected by prominent journals. Left unchecked, over time you end up with science journals that only present the survivors of the journal process – studies showing significance. Psychologists are calling it the File Drawer Effect. The studies that disprove or weaken the hypotheses of high-profile studies seem to get stuffed in the file drawer, so to speak. Many scientists are pushing for the widespread publication of replication, failure, and insignificance. Only then, they argue, will the science journals and the journalism that reports on them accurately describe the world being explored. Science above all will need to root out survivorship, but it won’t be easy. This particular bias is especially pernicious, said Plait, because it is almost invisible by definition. ”The only way you can spot it is to always ask: what am I missing? Is what I’m seeing all there is? What am I not seeing? Those are incredibly difficult questions to answer, and not always answerable. But if you don’t ask them, then by definition you can’t answer them.” He added. “It’s a pain, but reality can be a tough nut to crack.”

Failure to look for what is missing is a common shortcoming, not just within yourself but also within the institutions that surround you. A commenter at an Internet watering hole for introverts called the INTJForum explained it with this example: when a company performs a survey about job satisfaction the only people who can fill out that survey are people who still work at the company. Everyone who might have quit out of dissatisfaction is no longer around to explain why. Such data mining fails to capture the only thing it is designed to measure, but unless management is aware of survivorship bias things will continue to seem peachy on paper. In finance, this is a common pitfall. The economist Mark Klinedinst explained to me that mutual funds, companies that offer stock portfolios, routinely prune out underperforming investments. “When a mutual fund tells you, ‘The last five years we had 10 percent on average return,’ well, the companies that didn’t have high returns folded or were taken over by companies that were more lucky.” The health of the companies they offer isn’t an indication of the mutual fund’s skill at picking stocks, said Klinedinst, because they’ve deleted failures from their offerings. All you ever see are the successes. That’s true for many, many elements of life. Money experts who made great guesses in the past are considered soothsayers because their counterparts who made equally risky moves that failed nosedived into obscurity and are now no longer playing the game. Whole nations left standing after wars and economic struggles pump fists of nationalism assuming that their good outcomes resulted from wise decisions, but they can never know for sure.

“Let us suppose that a commander orders 20 men to invade an enemy bunker. This invasion leads to a complete destruction of the bunker and only one dead soldier from the 20 person team. An amazingly successful endeavor. Unless you are the one soldier who was shot through the head running up the hill. From his standpoint, rapidly ascending to the spirit world, it seems like a gigantic waste and a terrible order, but we will never hear his side of things. We will only hear from the guys who survived, how it was tough going until they made it over the rise. How it was sad to lose one guy, but they knew that they would make it. They just had a feeling. Of course, that one guy had that feeling to, until he felt nothing.” – Unknown author at spacetravelsacrime.blogspot.com

If you spend your life only learning from survivors, buying books about successful people and poring over the history of companies that shook the planet, your knowledge of the world will be strongly biased and enormously incomplete. As best I can tell, here is the trick: When looking for advice, you should look for what not to do, for what is missing as Phil Plait suggested, but don’t expect to find it among the quotes and biographical records of people whose signals rose above the noise. They may have no idea how or if they lucked up. What you can’t see, and what they can’t see, is that the successful tend to make it more probable that unlikely events will happen to them while trying to steer themselves into the positive side of randomness. They stick with it, remaining open to better opportunities that may require abandoning their current paths, and that’s something you can start doing right now without reading a single self-help proverb, maxim, or aphorism. Also, keep in mind that those who fail rarely get paid for advice on how not to fail, which is too bad because despite how it may seem, success boils down to serially avoiding catastrophic failure while routinely absorbing manageable damage.

Abraham Wald – Source: Prof. Konrad Jacobs

Before we depart, I’d like to mention Wald one more time. Like many of the others who joined the armed services to fight Hitler with numbers, Abraham Wald went down in history, but not for the bombers and bullet holes story. He is best remembered as the inventor of sequential analysis, another achievement he earned while working in the department of war math. He married Lucille Land in 1941. Two years later they had their first child, Betty, followed four years later by another they named Robert. Three years after that, at the top of his career and enjoying an exotic speaking tour, after saving the lives of thousands of people he would never meet, he and Lucille died in an airplane that crashed against the side of the Nilgiri mountains in India. Perhaps there is an irony to that, something about airplanes and odds and chance and luck, but it isn’t the interesting part of Wald’s story. His contributions to science are what survives his time on Earth and the parts of his tale that will endure.

In 1968, the National Academy of Sciences issued a report saying the application of mathematics in World War II “became recognized as an art,” and the lessons learned by the mathematicians were later applied to business, science, industry, and management. They saved the world and then rebuilt it using the same tools each time – calculators and chalk.

In 1978, Allen Wallis, Director of SRG said of his team, “This was surely the most extraordinary group of statisticians ever organized.” The bomber problem was just a side story for them, a funny anecdote that only surfaced in the 1980s as they all began to reminisce full time. When you think of how fascinating the story is, it makes you wonder about the stories we’ll never hear about those numerical soldiers because they never made it out of the war and into a journal, magazine, or book, and how that’s true of so much that’s important in life. All we know of the past passes through a million, million filters, and a great deal is never recorded or is tossed aside to make room for something more interesting or beautiful or audacious. All we will learn from history reaches us from the stories that, for whatever reason, survived.

I wrote a whole book full of articles like this one: You Are Now Less Dumb – Get it now!

I wrote a whole book full of articles like this one: You Are Now Less Dumb – Get it now!

Amazon | B&N | BAM | Indiebound | iTunes

Go deeper into understanding just how deluded you really are and learn how you can use that knowledge to be more humble, better connected, and less dumb in the sequel to the internationally bestselling You Are Not So Smart. Watch the beautiful new trailer here.

Sources

- Smith, M. D., Wiseman, R. & Harris, P. (2000). The relationship between ‘luck’ and psi. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 94, 25-36.

- Smith, M. D., Wiseman, R., Harris, P. & Joiner, R. (1996). On being lucky: The psychology and parapsychology of luck. European Journal of Parapsychology, 12, 35-43.

- Wolfowitz, J. “Abraham Wald, 1902-150.” The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 23.1 (1952): 1-13.